1. Introduction

In modern times, the relationship between man and death assumes different connotations, even of grim appeal. To cite just one, the postmortem picture tradition arose in the Victorian age and disappeared only after World War II, although it persists in parts of Eastern Europe [

1].

This interest led different players in the cultural industry to install the theme of death within their narrative strategy, with tourism being one of them. In the last decade, the so-called phenomenon of “dark tourism” has been consistently developing. Tourists plan and organize their travel according to the theme of death, a long-lasting topic for the lure.

Human mummies may represent an example of such a process: people may purposefully enjoy mummies for study, curiosity, or specifically in the frame of dark tourism. Their exhibition represents a scientific and cultural offering able to generate economic and territorial impact [

2]. This work aims to understand whether and how the display of mummies may induce a significant impact in places with a low potential for cultural tourism proposals.

2. Methodology

The analysis started by identifying all Italian sites where mummies are present, including institutions where mummies are not displayed to the public but whose presence is communicated. Such a mapping, which is currently being implemented and whose initial results are shown in

Figure 1, provides an initial overview of the distribution throughout the country. It also highlights conservation, exhibition, and musealization aspects, if any. Such a job also allows one to identify the type of proposal to the public, both in terms of communication and actual services to the visitor and the territory.

Audience data from each place (i.e., museum/church/catacomb/etc.) where mummies are present were collected in order to have a tool for analysis. However, in most cases, it was impossible to track down published data or to retrieve any information directly from the institutions contacted by phone. Consequently, the work presented here was elaborated on through an analytical study of the communication and press review of individual places.

The analysis included both direct strategic communication (i.e., planned and executed directly by the public institution) and indirect communication, taking into account narrative products about cultural places not directly produced by the managing institution. For each of these, three indexes have been identified: the relationship of cultural places with the surrounding area; the official communication channels of cultural places and their strategy; and feedback from the public, not only in terms of participation but also in terms of narrative response through digital channels.

3. National Survey

Only mummified human remains in a state of integrity, spanning from good to excellent conditions, were considered. Isolated parts, often used and displayed as relics, were not examined, as they were misleading for the kind of analysis in the present work. Both human mummies preserved in Laic and Catholic places were included. The bodies of saints and blessed individuals were mapped (fundamental, in this, Fulcheri 1996 [

3], expanded and updated), but they were not included in the survey due to their religious significance, which would bias the analysis.

A database of approximately 170 spatial items was created starting from the information in Fornaciari, Giuffra 2006 [

4] and Fornaciari 2007 [

5], revised and supplemented (

Figure 2).

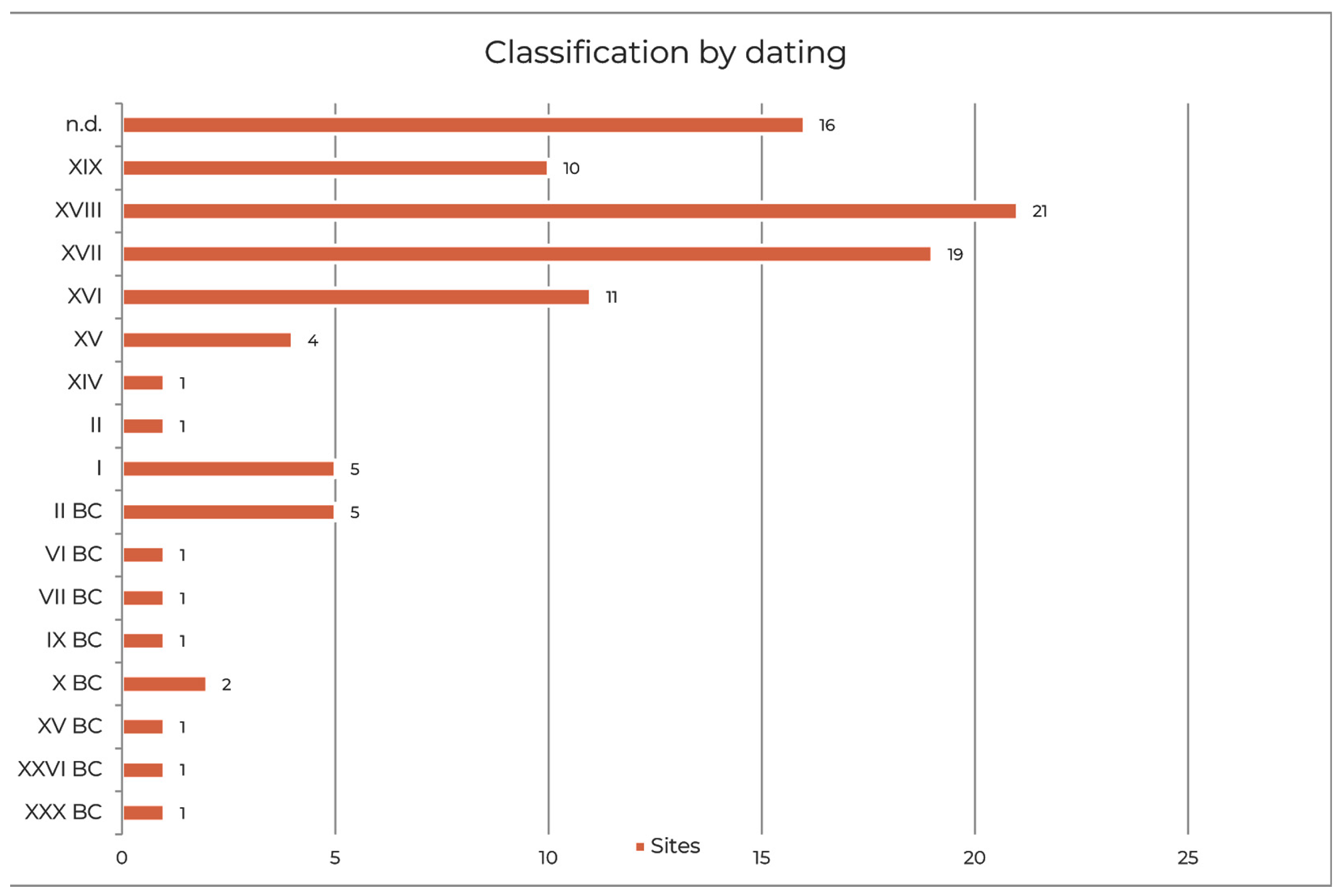

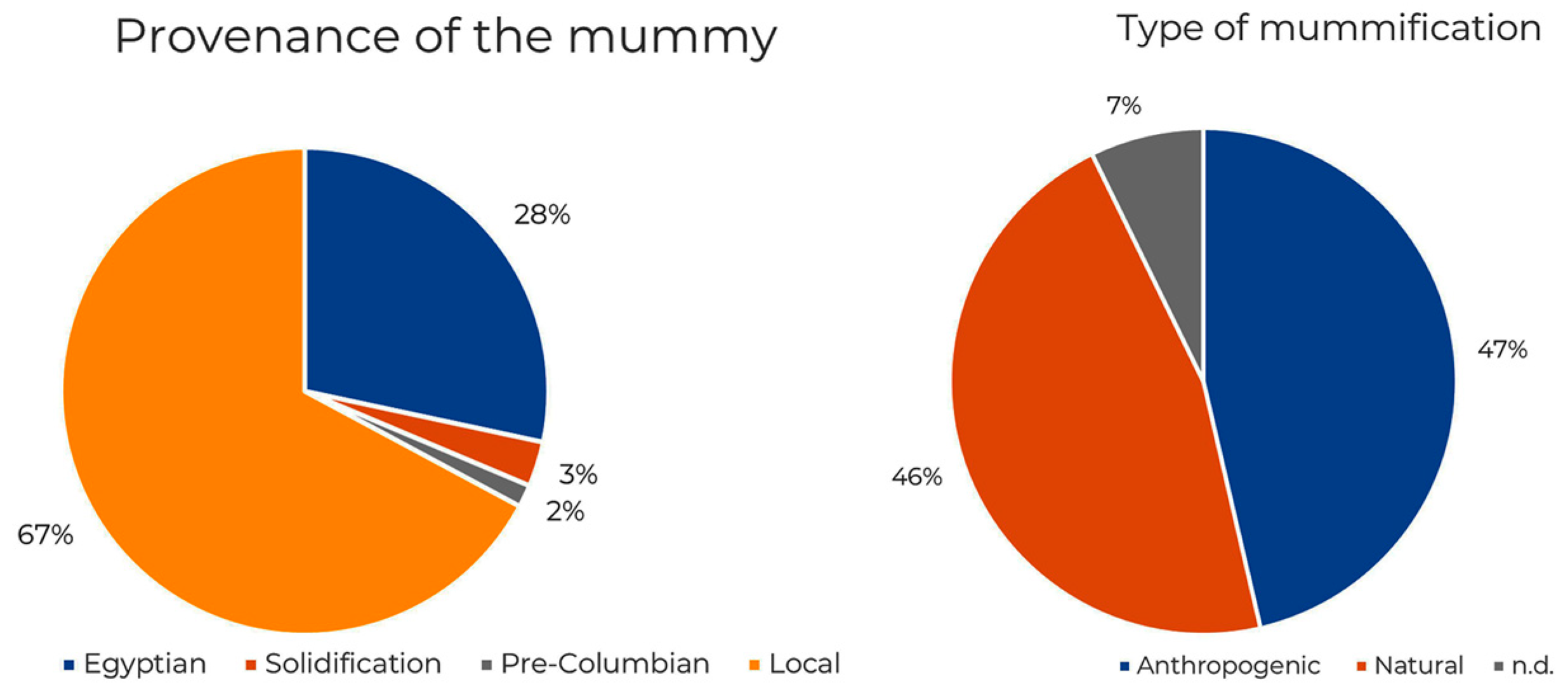

Cataloguing was performed according to the location site, the typology of mummification (natural, artificial), the type of musealization, and the dating (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Whenever possible, the following elements have been inspected: if the exhibit was focused exclusively on the mummies or if they were part of a broader itinerary, for example along a museum exhibition path; if mummies were accessible by a wide public, and not only by specialists or by request and, finally, if there was any form of ticketing.

For each entry, the strategic relevance of the communication and the activated channels were analyzed too; additionally, the comments and opinions of the visitors were tracked and classified to support the analysis of the digital reputation of the mapped entities as part of an ongoing territorial sentiment analysis.

Alongside the cataloguing activity, the mapping activity was carried out using GIS (Geographical Information System) tools. It was possible to make the information, which was recorded in the database, interact with its territorial context. Such an operation allowed for the possibility of analyzing not only distribution on the national territory but also the relational capacity of the mapped entity with infrastructures, with other points of territorial interest, and the eventual connection to tourist flows insisting in the area.

4. Case Studies

The case studies analyzed are three museums located, respectively, in Ferentillo, Roccapelago, and Burgio. They were chosen because, before the exhibition of the mummies, they did not record significant tourist flows. Moreover, these museums are in territories with a strong tourism tradition.

4.1. Ferentillo (TR)–Umbria

The territory of the Valnerina is typically associated with tourism attracted by many sports and nature activities, as well as by itineraries such as the Way of St. Benedict.

In 2016, this territory was afflicted by an earthquake, which led to the discovery of numerous human mummies and, therefore, to an increase in cultural tourism due to the growing flow of visitors, attracted precisely by these findings. The exhibition in the “Museum of Mummies” resulted in the arrival of nearly 150 daily visitors in the April–October period (2019 data), with a significant difference between foreign and Italian visitors: the former went to the museum specifically for the mummies, the latter mostly discovered it during field trips.

This happens despite the perceived lack of a communication strategy; although the museum has a website, there is no possibility of booking services and tickets online. In addition, apart from common press articles, it appears that the institution is not running any active promotion or marketing strategy. The main cause of such an increase has therefore been ascribed to a substantial interest in so-called “transit tourism”, which is currently not allowing the village to make the fundamental transition from destination to tourist attraction.

4.2. Roccapelago (MO)–Emilia–Romagna

The place is located in the Modena district and is perfectly integrated into the tourist fabric of its host territory and on the website. The official channels managed by the municipality (

http://www.museomummieroccapelago.com/ accessed on 1 March 2022) give a clear sign of this: in the main menu, information is given not only about the museum and the mummies present but also about the itineraries of the area and the nearby villages.

The museum’s primary purpose is to become a central cultural hub acting as a vector to other destinations. Therefore, the desire emerges to use its heritage to engage the community and society around the museum. Pages about fundraising, volunteering, and even the more educational pages about mummies are real community-building tools. They aim to increase museum engagement and push the adoption of new participatory forms of fruition.

Compared to the case of Ferentillo, there is a smaller audience growth in the short term due to the reduced impact of passing tourism, balanced by a long-term increase in fidelity and constant growth.

4.3. Burgio (AG)–Sicily

The Burgio Mummy Museum represents another aspect of the development of new tourist flows. The religious value of the cultural site and the great naturalistic asset associated with the Sosio River represent a tourist alternative to the more classic historical-archaeological routes in the Agrigento area. Such an aim emerges from an analysis of the press review of the post-pandemic emergency reopening, which has not been followed by an effective communication effort by the public administration.

There is a website (

https://www.comune.burgio.ag.it/museodellemummie accessed on 1 March 2022), encompassing some strongly didactic social content about the museum and the mummies, but no comprehensive visitor service information is provided, nor are there services through the web. Through the analysis of online feedback from the public, a strong desire is evident for more information on-site or to arrange their visit in advance through online channels, also attracted by the religious significance represented by these anthropological remains for the area.

5. Conclusions

From the preliminary survey work carried out several insights emerge regarding the impact that a proper and respectful valorization of human mummies manages to generate in a territory, independently from its urbanization degree. There are various kinds of problems related to communication, caused essentially by the lack of a strategy and, at times, by the lack of perception of the historical and archaeological value of these relics. That is why this study identified some cases of inadequate valorization, focused exclusively on the macabre aspect rather than on the cultural and scientific significance, or of an unaccomplished network strategy, resulting in the separation of the mummy from its territorial context. The development of this work will involve gradual expansion into the international context. Moreover, our next aim is to investigate the impact of this topic in contexts of cultural competition.

This analysis therefore provides valuable indications: firstly on the correct strategies of valorization, secondly on the design of museum layouts respecting the bioethical value of such testimonies and at the same time allowing for growing segments of the public to get involved, and, finally, on the creation of territorial networks in which to implement tourist–cultural synergies with a consequent wide-ranging economic impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M., L.L. and S.G.M.; methodology, R.M., L.L. and S.G.M.; Survey analysis, S.G.M. and E.B.; validation R.M. and L.L., writing—original draft preparation, R.M., L.L. and S.G.M.; writing—review and editing, R.M., E.B. and S.G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Orlando, M. Fotografia Postmortem; Castelvecchi: Roma, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tosi, S. Turismo, morte e dolore. Una riflessione sociologica intorno al tema del turismo dark. In Dossier Spostarsi Nel Tempo. Esperienze Emiliano-Romagnole di Viaggi Della Memoria e Nella Memoria; Rivista degli Istituti Storici dell’Emilia-Romagna in Rete: Bologna, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fulcheri, E. Mummies of Saints: A particular category of Italian mummies. In Human Mummies: A Global Survey of Their Status and the Techniques of Conservation; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1996; pp. 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fornaciari, G.; Giuffra, V. La Mummificazione nella Sicilia della tarda Età Moderna (secoli XVIII-XIX): Nuove testimonianze dalla Sicilia Orientale. Med. Nei Secoli 2006, 18, 925–942. [Google Scholar]

- Fornaciari, G. Le mummie in Italia. Med. E Cult. 2007, 70. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).