Measuring Running Workload and Key Points during Treadmill Running Using a Custom Build ‘Nodes’ System †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

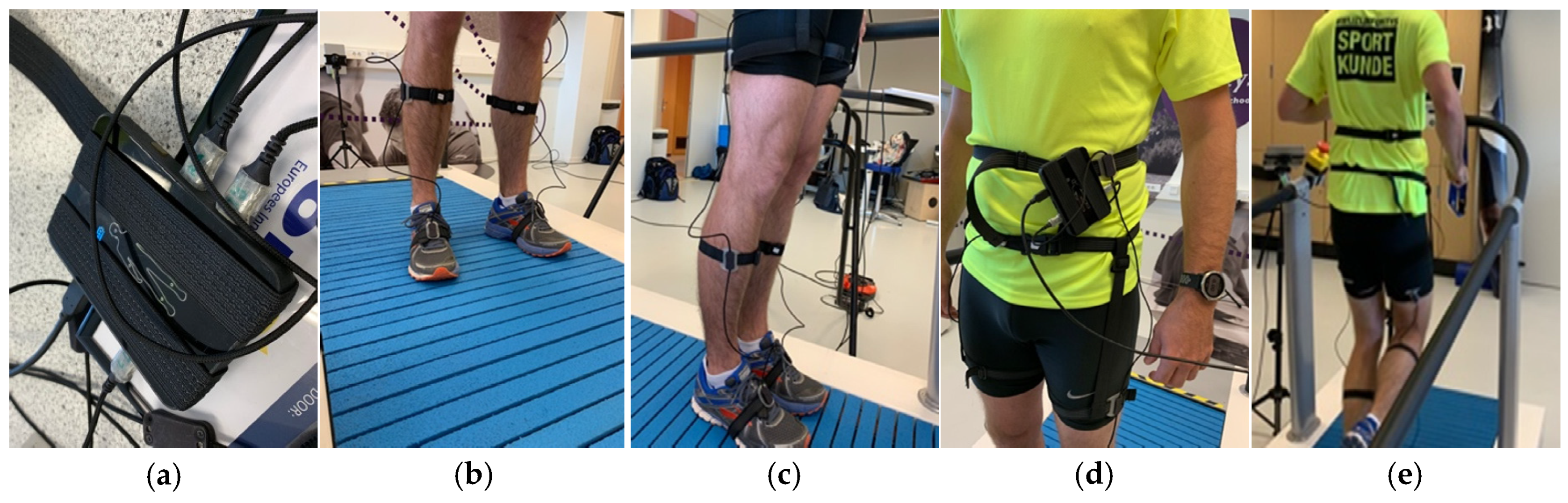

2.2. Technical Description of the Nodes System

2.3. Experimental Protocol

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vos, S.; Janssen, M.; Goudsmit, J.; Lauwerijssen, C.; Brombacher, A. From Problem to Solution: Developing a Personalized Smartphone Application for Recreational Runners following a Three-step Design Approach. Procedia Eng. 2016, 147, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerder, J.; Breedveld, K.; Borgers, J. Running across Europe: The Rise and Size of One of the Largest Sport Markets; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781137446374. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.; Scheerder, J.; Thibaut, E.; Brombacher, A.; Vos, S. Who uses running apps and sports watches? Determinants and consumer profiles of event runners’ usage of running-related smartphone applications and sports watches. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P.U.; Pyne, D.B.; Telford, R.D.; Hawley, J.A. Factors Affecting Running Economy in Trained Distance Runners. Sports Med. 2004, 34, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hooren, B.; Goudsmit, J.; Restrepo, J.; Vos, S. Real-time feedback by wearables in running: Current approaches, challenges and suggestions for improvements. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohrmann, C.; Seiter, J.; Llorca, Y.; Tröster, G. Can smartphones help with running technique? Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 19, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adesida, Y.; Papi, E.; McGregor, A.H. Exploring the role of wearable technology in sport kinematics and kinetics: A systematic review. Sens. Switz. 2019, 19, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, I.S. Is There an Economical Running Technique? A Review of Modifiable Biomechanical Factors Affecting Running Economy. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, K.R.; Kilding, A.E. Running economy: Measurement, norms, and determining factors. Sports Med. Open 2015, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudsmit, J.; Janssen, M.; Luijten, S.; Vos, S. Tailored Feedback Requirements for Optimal Motor Learning: A Screening and Validation of Four Consumer Available Running Wearables. Proceedings 2018, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2M Engineering Nodes System. Available online: https://www.2mel.nl/project/nodes-9dof-motion-suit-for-vr-rehabilitation-gaming/ (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- Hafer, J.F.; Brown, A.M.; DeMille, P.; Hillstrom, H.J.; Garber, C.E. The effect of a cadence retraining protocol on running biomechanics and efficiency: A pilot study. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, J.R.; Silder, A.; Montgomery, K.L.; Fredericson, M.; Delp, S.L. Acute changes in foot strike pattern and cadence affect running parameters associated with tibial stress fractures. J. Biomech. 2018, 76, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, K.A.; Nigg, B.M. Muscle activity in the leg is tuned in response to impact force characteristics. J. Biomech. 2004, 37, 1583–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, T. Biomechanics and running economy. Sports Med. 1996, 22, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, I.S.; Jones, A.M.; Dixon, S.J. Mechanisms for improved running economy in beginner runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 1756–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.R.; Cavanagh, P.R. Relationship between distance running mechanics, running economy, and performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 1987, 63, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyröläinen, H.; Belli, A.; Komi, P.V. Biomechanical factors affecting running economy. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 1330–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ruiter, C.J.; Verdijk, P.W.L.; Werker, W.; Zuidema, M.J.; de Haan, A. Stride frequency in relation to oxygen consumption in experienced and novice runners. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2014, 14, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, J.X.; Zhou, J.H. Comparison of plantar loads during treadmill and overground running. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Key Point | Description | Evidence for Running | Measured with |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cadence | The number of steps per minute | Higher cadence relates to a lower injury rate [12,13]. | Wearable sensors |

| Impact force direction | Ground reaction force direction at impact | For the leg to handle the impact the best, the shin angle should be aligned with the ground reaction force vector [14]. | Force plate, or sensors on lower leg |

| Body angle | Lean of the torso related to the vertical vector | Forward body lean seems to have beneficial effects on running economy and may induce other factors as well [10,15]. | Wearable chest sensor |

| Knee extension | Angle between upper and lower leg measured at toe-off | Smaller angle improves running performance and economy, the foot gets a better swing phase [16]. | Two sensors, one on the lower and one on the upper leg |

| Minimal impact G | Impact force | Lower peak medial–lateral force [17], lower anterior–posterior braking force [18], and higher anterior–posterior propulsive force [16] are more economical | Wearable research prototypes. |

| Trial | Cadence (SPM) | Cadence (norm) | Heart Rate (BPM) | Heart Rate (norm) | RPE | RPE (norm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T100%self | 165.1 (9.6) | 100.3% (1.7) | 142 (24) | 95.5% (2.5) | 5.6 (0.5) | 85.6% (8.0) |

| T92% | 152.3 (8.6) | 92.5% (0.9) | 150 (27) | 100.18% (2.2) | 7.0 (0.8) | 107.8% (13.4) |

| T96% | 158.3 (8.6) | 96.2% (0.4) | 149 (27) | 99.9% (1.0) | 6.6 (0.5) | 101.0% (8.0) |

| T100% | 164.6 (8.7) | 100.0 (0.4) | 148 (26) | 99.23% (0.9) | 6.3 (0.5) | 96.5% (4.0) |

| T104% | 170.4 (9.2) | 103.6% (0.6) | 149 (27) | 99.7% (1.1) | 6.4 (0.8) | 98.5% (7.9) |

| T108% | 177.3 (8.3) | 107.8% (1.0) | 151 (26) | 101.0% (1.6) | 6.3 (1.0) | 96.2% (10.4) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goudsmit, J.; Giudici, S.L.; Herweijer, J.; Vos, S. Measuring Running Workload and Key Points during Treadmill Running Using a Custom Build ‘Nodes’ System. Proceedings 2020, 49, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2020049030

Goudsmit J, Giudici SL, Herweijer J, Vos S. Measuring Running Workload and Key Points during Treadmill Running Using a Custom Build ‘Nodes’ System. Proceedings. 2020; 49(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2020049030

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoudsmit, Jos, Stella Lo Giudici, Janine Herweijer, and Steven Vos. 2020. "Measuring Running Workload and Key Points during Treadmill Running Using a Custom Build ‘Nodes’ System" Proceedings 49, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2020049030

APA StyleGoudsmit, J., Giudici, S. L., Herweijer, J., & Vos, S. (2020). Measuring Running Workload and Key Points during Treadmill Running Using a Custom Build ‘Nodes’ System. Proceedings, 49(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2020049030