Towards a Taxonomy of Feedback Factors Affecting the User Experience of Augmented Reality Exposure Therapy Systems for Small-Animal Phobias †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

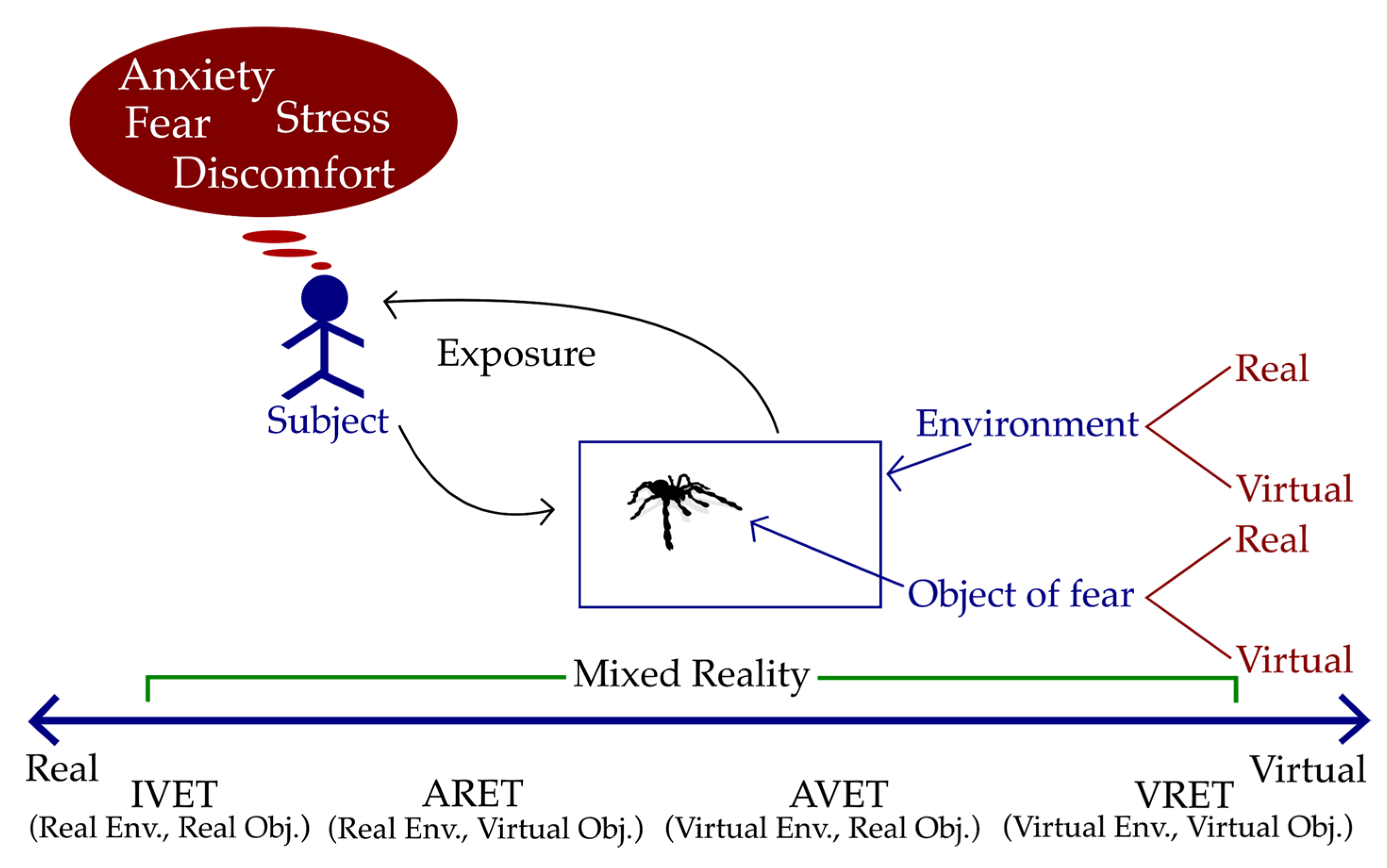

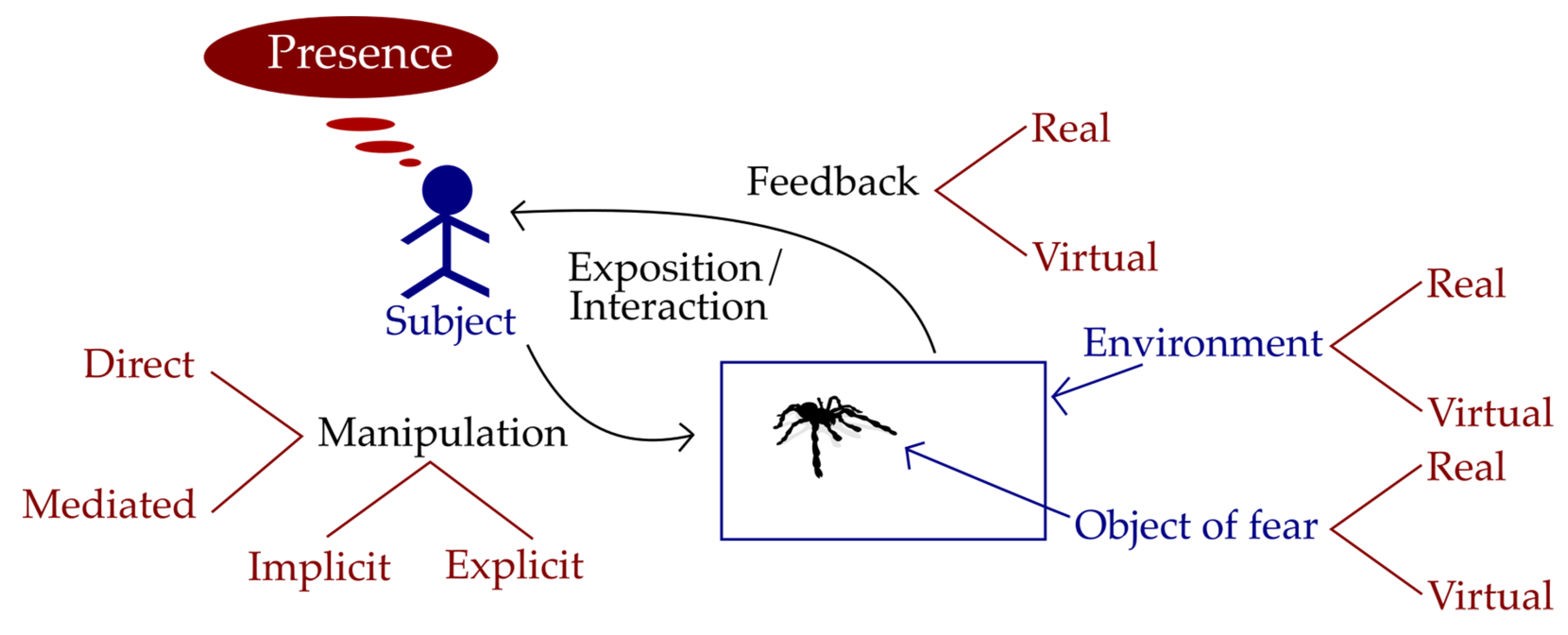

2. Mixed Reality Technologies for Exposure Therapies

3. Method

- RQ1: What are the design features of AR mobile applications for small animal phobia treatment?

- RQ2: How do these attributes impact the experience of use of the participants?

- -

- Studies that present mobile applications for the treatment of phobias to small animals.

- -

- Studies that indicate or evaluate design aspects that impact the user experience.

- -

- The following criteria state when a study was excluded:

- -

- Studies that do not explain the design characteristics of the applications or that are focused on the effectiveness of the treatment.

- -

- Mobile applications for other phobias.

- -

- Studies presenting non-peer reviewed material.

4. Augmented Reality Exposure Therapy Systems for Small-Animal Phobias

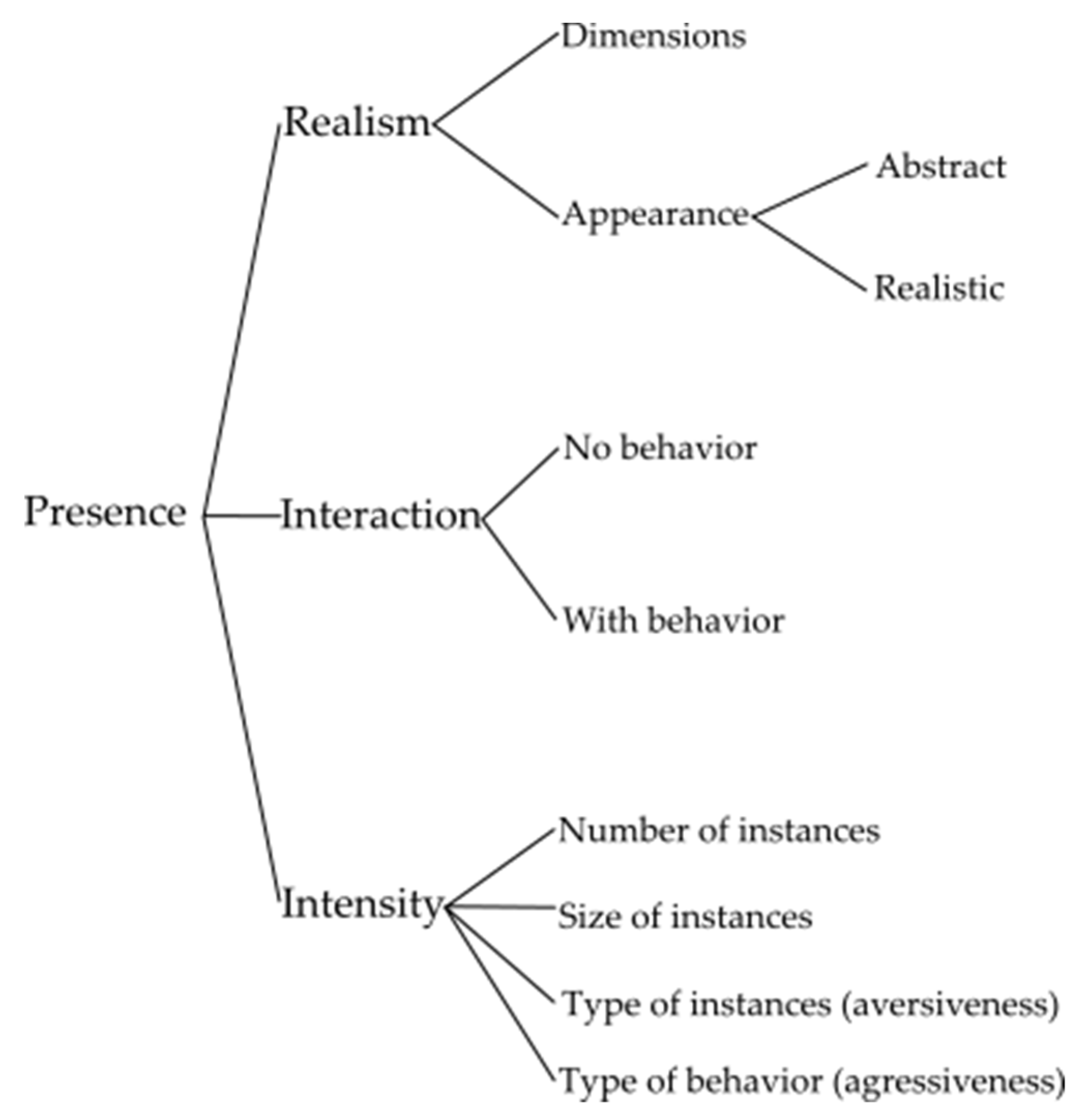

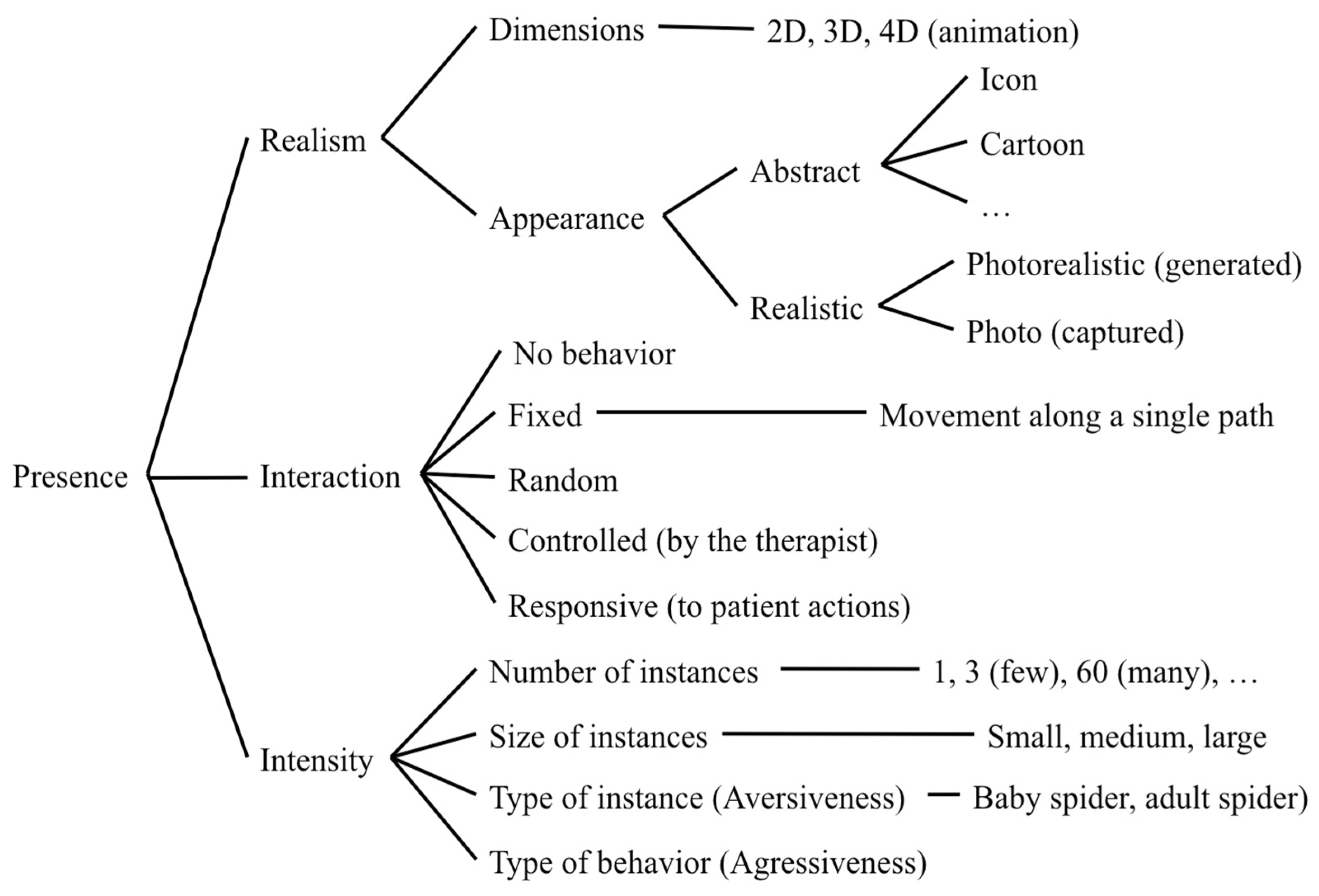

5. Proposed Taxonomy of Factors that Affect the Experience of Use of ARET Systems for Small-Animal Phobias

- (a)

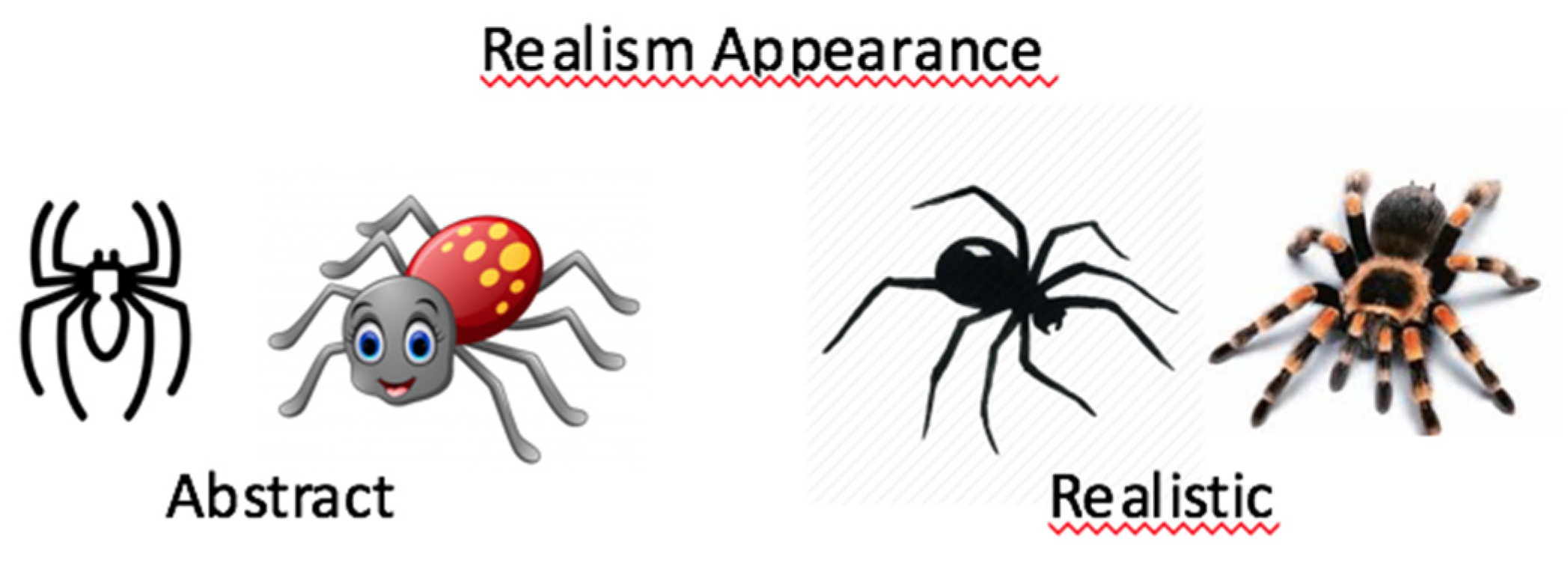

- Realism refers to the degree of convergence between the user’s expectations and the current experience of the virtual element [46]. It is defined by: (a) the number of dimensions in which the object is presented, and (b) the appearance of the object, which may correspond to reality or be an abstraction. For example, in Juan, Alcaniz et al. [35] cockroaches are presented in 3D using realistic images, while in Ramírez-Fernández et al. [23] the spider can be presented in 2D or 3D and as a cartoon or as a picture of a real spider.

- (b)

- Interaction refers to the presence or absence of interactive elements that react (or not) to the actions of the user. Thus, the interaction is defined primarily by the absence or presence of behavior. Then, if there is behavior, it can be: (a) fixed and with a unique pattern; (b) random; (c) controlled by the therapist; or (d) responsive, that is, that responds dynamically to the patient’s actions. For example, in Botella, Breton-López et al. [16], during the game the objects of fear (spiders or cockroaches) appear in a predefined way. On the other hand, in Botella, Pérez-Ara et al. [11] the objects of fear are activated when the camera detects the included markers, and in Twiz Spider Phobia [37], the spider moves its extremities according to the detected proximity of the user.

- (c)

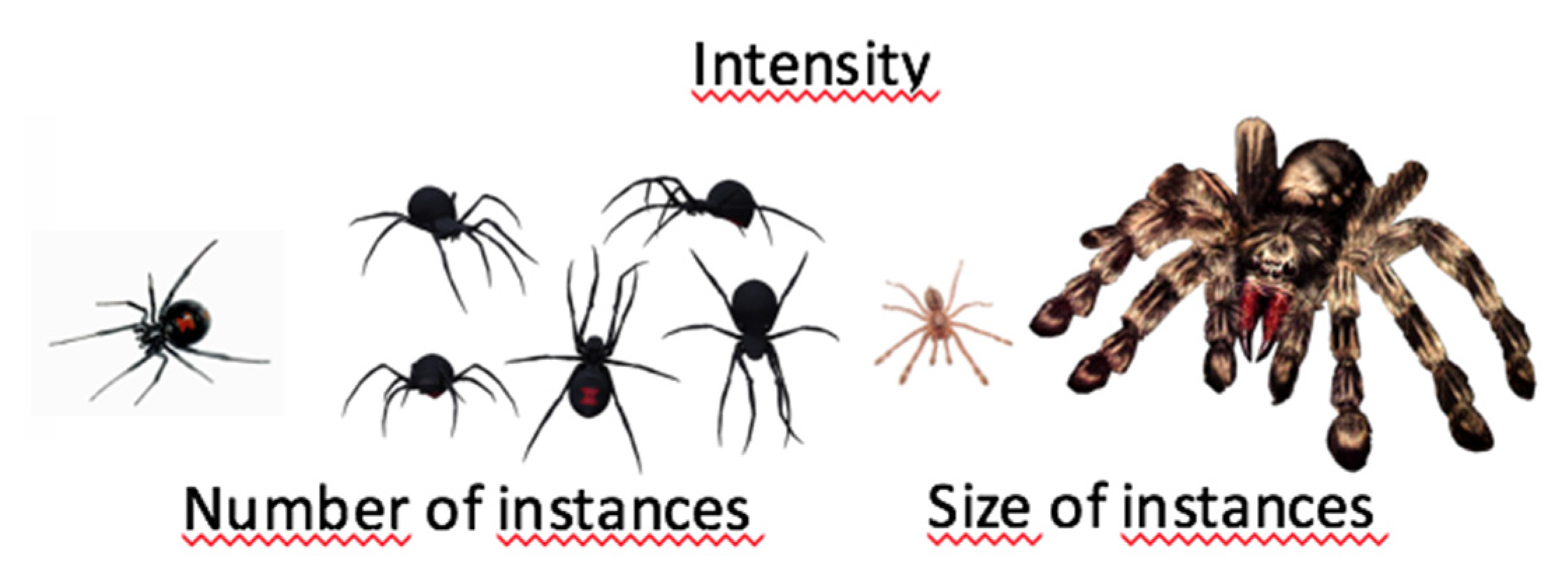

- Intensity refers to the levels of variability of the object that is used as a stimulus. This include: (a) the number of instances, (b) the size of the instance, (c) the type or aversiveness of the instance (e.g., a little mouse, a young rat, or an old and dirty rat), (d) the type of behaviour or aggressiveness level of the instance (e.g., a temerous dog, a happy dog, or an aggressive dog). For example, as described in Botella, Pérez-Ara et al. [11], in several of the systems we found that the type (e.g., tarantula or black widow), size (e.g., large, medium, small) and number of objects (e.g., from 1 to 60) can be specified by the therapist to progressively adapt the treatment, modifying gradually the intensity of its effect.

6. Discussion, Conclusions and Future Work

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Errera, P. Some historical aspects of the concept phobia. Psychiatr. Q. 1962, 36, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.; Petukhova, M.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Wittchen, H.U. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 21, 169–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0890425558. [Google Scholar]

- Öst, L.-G. One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behav. Res. Ther. 1989, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öst, L.-G.; Salkovskis, P.M.; Hellström, K. One-session therapist-directed exposure vs. self-exposure in the treatment of spider phobia. Behav. Ther. 1991, 22, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, I.M.; Mathews, A.M. Brief standard self-rating for phobic patients. Behav. Res. Ther. 1979, 17, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Palacios, A.; Hoffman, H.G.; See, S.K.; Tsai, A.; Botella, C. Redefining therapeutic success with virtual reality exposure therapy. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2001, 4, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Palacios, A.; Botella, C.; Hoffman, H.; Fabregat, S. Comparing Acceptance and Refusal Rates of Virtual Reality Exposure vs. In Vivo Exposure by Patients with Specific Phobias. CyberPsychology Behav. 2007, 10, 722–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T.D.; Rizzo, A.A. Affective outcomes of virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety and specific phobias: A meta-analysis. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2008, 39, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, M.B.; Emmelkamp, P.M.G. Virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2008, 22, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, C.; Pérez-Ara, M.Á.; Bretón-López, J.; Quero, S.; García-Palacios, A.; Baños, R.M. In Vivo versus augmented reality exposure in the treatment of small animal phobia: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, S.; Dumoulin, S.; Robillard, G.; Guitard, T.; Klinger, E.; Forget, H.; Loranger, C.; Roucaut, F.X. Virtual reality compared with in vivo exposure in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A three-arm randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botella, C.; Fernández-álvarez, J.; Guillén, V.; García-palacios, A.; Baños, R. Recent Progress in Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Phobias : A Systematic Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baus, O.; Bouchard, S. Moving from virtual reality exposure-based therapy to augmented reality exposure-based therapy: A review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, M.C.; Joele, D. A comparative study of the sense of presence and anxiety in an invisible marker versus a marker augmented reality system for the treatment of phobia towards small animals. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2011, 69, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, C.; Breton-López, J.; Quero, S.; Baños, R.M.; García-Palacios, A.; Zaragoza, I.; Alcaniz, M. Treating cockroach phobia using a serious game on a mobile phone and augmented reality exposure: A single case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, A.; Finlay, J.; Abowd, G.; Beale, R. Human-Computer Interaction, 3rd. ed.; Pearson/Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vitense, H.; Jacko, J.; Emery, V. Multimodal feedback: An assessment of performance and mental workload. Ergonomics 2003, 46, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, S.; Bouchard, S. Virtual Reality Exposure for Phobias: A critical review. J. Cyber Ther. Rehabil. 2008, 1, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Quero, S.; Nebot, S.; Rasal, P.; Bretón-lópez, J.; Baños, R.M.; Botella, C. Las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación en el Tratamiento de la Fobia a Animales Pequeños en la Infancia. Behav. Psychol. 2014, 22, 255–274. [Google Scholar]

- Breton-López, J.; Quero, S.; Botella, C.; García-Palacios, A.; Baños, R.; Alcañiz, M. An Augmented Reality System Validation for the Treatment of Cockroach Phobia. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, 13, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, M.C.; Calatrava, J. An augmented reality system for the treatment of phobia to small animals viewed via an optical see-through HMD: Comparison with a similar system viewed via a video see-through HMD. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2011, 27, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Fernández, C.; Morán, A.L.; García-Canseco, E.; Meza-Kubo, V.; Barreras, E.; Valenzuela, O.; Hernández, N. Haptic Mobile Augmented Reality System for the Treatment of Phobia of Small Animals in Tennagers. In Ubiquitous Computing and Ambient Intelligence; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Volume 7656, pp. 666–676. ISBN 978-3-642-35376-5. [Google Scholar]

- Alice, I.; Giglioli, C.; Pallavicini, F.; Pedroli, E.; Serino, S.; Riva, G.; Chicchi Giglioli, I.A.; Pallavicini, F.; Pedroli, E.; Serino, S.; et al. Augmented Reality: A Brand New Challenge for the Assessment and Treatment of Psychological Disorders. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Palacios, A.; Hoffman, H.; Carlin, A.; Furness, T.A.; Botella, C. Virtual reality in the treatment of spider phobia: A controlled study. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinck, M.; Koene, M.; Telli, S.; Moerman-van den Brink, W.; Verhoeven, B.; Becker, E.S. The time course of location-avoidance learning in fear of spiders. Cogn. Emot. 2015, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaliszyn, D.; Marchand, A.; Bouchard, S.; Martel, M.O.; Poirier-Bisson, J. A randomized, controlled clinical trial of in virtuo and in vivo exposure for spider phobia. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, 13, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiban, Y.; Schelhorn, I.; Pauli, P.; Mühlberger, A. Effect of combined multiple contexts and multiple stimuli exposure in spider phobia: A randomized clinical trial in virtual reality. Behav. Res. Ther. 2015, 71, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloff, A.; Lindner, P.; Hamilton, W.; Reuterskiöld, L.; Andersson, G. Single-session gamified virtual reality exposure therapy for spider phobia vs. traditional exposure therapy: Study protocol for a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Trials 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesien, M.; Botella, C.; Bretón-López, J.; Del Río González, E.; Burkhardt, J.M.; Alcañiz, M.; Pérez-Ara, M.Á. Treating small animal phobias using a projective-augmented reality system: A single-case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 49, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.; Vakkalanka, S.; Kuzniarz, L. Guidelines for conducting systematic mapping studies in software engineering: An update. Inf. Softw. 2015, 64, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, M.C.; Botella, C.; Alcañiz, M.; Baños, R.; Carrion, C.; Melero, M.; Lozano, J.A. An augmented reality system for treating psychological disorders: Application to phobia to cockroaches. In Proceedings of the ISMAR 2004 IEEE and ACM International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, Arlington, VA, USA, 2–5 November 2004; pp. 256–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpe, J. The Practice of Behavior Therapy; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, M.C.; Alcaniz, M.; Monserrat, C.; Botella, C.; Banos, R.M.; Guerrero, B. Using Augmented Reality to Treat Probias. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2005, 25, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, J.; O’Donohue, W. Fear of Spiders Questionnaire. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1995, 26, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twiz Spider Phobia. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.TwizWeb.SpiderPhobiaVRAR&hl=es (accessed on 24 February 2018).

- Rich Apps 4D Spider on a Hand Simulator. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.richappsandgames.spideronahandsimulator (accessed on 28 February 2018).

- Weber, B.; Sagardia, M.; Hulin, T.; Preusche, C. Visual, Vibrotactile, and Force Feedback of Collisions in Virtual Environments: Effects on Performance, Mental Workload and Spatial Orientation. VAMR/HCII Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2013, 1, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Burdea, G.C. Haptic Feedback for Virtual Reality. Proceedings of International Workshop on Virtual prototyping. 1999; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Saddik, A. El Chapter 4: Machine Haptics. In Haptics Technologies, Springer Series on Touch and Haptic Systems; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 67–103. [Google Scholar]

- Saddik, A.; Orozco, M.; Eid, M.; Cha, J. Chapter 5: Computer Haptics. In Haptics Technologies, Springer Series on Touch and Haptic Systems; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 105–143. [Google Scholar]

- Agah, A. Human interactions with intelligent systems : Research taxonomy. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2001, 27, 71–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deol, K.K.; Sutcliffe, A.; Maiden, N. Modeling Interaction to Inform Information Requirements in Virtual Environments. 1999. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6cd2/0cfa5b0d146696b5bf04116e1f59462a8413.pdf#page=121 (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Wrzesien, M.; Burkhardt, J.M.; Alcañiz, M.; Botella, C. How technology influences the therapeutic process: A comparative field evaluation of augmented reality and in vivo exposure therapy for phobia of small animals. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci 2011, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, R.M.; Guillen, V.; Quero, S.; García-Palacios, A.; Alcaniz, M.; Botella, C. A virtual reality system for the treatment of stress-related disorders: A preliminary analysis of efficacy compared to a standard cognitive behavioral program. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2011, 69, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Configuration Type | Level of Exposition | Feedback | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual | Auditory | Haptic | |||

| [30] | MT | AC | 3D, R, AI, RF, DS | N, S | NI |

| [31] | MT | AC | 3D, R, AI, RF, DS, F, | N, S | NI |

| [12] | MT | AC | 3D, R, AI, RF, DS, F | N, S | NI |

| [13] | MT | AC | 3D, C, AnI, NA, DS, F | NI | NI |

| [8] | MT | AC | 3D, R, AI, RF, DS, | NI | NI |

| [21] | AS | ApA | 2D or 3D, C or R, I or AnI, NA, US, F | E or N, S | Si, S |

| [32] | NI | SL | 3D, R, AI, RR, US, F | NI | NI |

| [33] | NI | SL | 3D, C and R, AnI, RF, US, F | N, S | NI |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramírez-Fernández, C.; Morán, A.L.; Meza-Kubo, V. Towards a Taxonomy of Feedback Factors Affecting the User Experience of Augmented Reality Exposure Therapy Systems for Small-Animal Phobias. Proceedings 2018, 2, 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2191252

Ramírez-Fernández C, Morán AL, Meza-Kubo V. Towards a Taxonomy of Feedback Factors Affecting the User Experience of Augmented Reality Exposure Therapy Systems for Small-Animal Phobias. Proceedings. 2018; 2(19):1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2191252

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamírez-Fernández, Cristina, Alberto L. Morán, and Victoria Meza-Kubo. 2018. "Towards a Taxonomy of Feedback Factors Affecting the User Experience of Augmented Reality Exposure Therapy Systems for Small-Animal Phobias" Proceedings 2, no. 19: 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2191252

APA StyleRamírez-Fernández, C., Morán, A. L., & Meza-Kubo, V. (2018). Towards a Taxonomy of Feedback Factors Affecting the User Experience of Augmented Reality Exposure Therapy Systems for Small-Animal Phobias. Proceedings, 2(19), 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2191252