1. Introduction

Climate change is reshaping the conditions under which agriculture operates, with rising temperatures, altered precipitation regimes, and more frequent extremes affecting crop stability, quality, and farm economics [

1,

2,

3]. Evidence from global and regional studies points to measurable yield losses associated with heatwaves and droughts, alongside growing variability that complicates planning and investment decisions at the farm level [

4,

5]. Mediterranean settings, such as Greece, are especially exposed due to water stress and high summer heat, making near-term adaptation a priority for sustaining productivity and rural livelihoods [

2,

3].

A substantial literature has sought to quantify farm adaptation through composite metrics. Vulnerability- and livelihood-based indices combine exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity to compare contexts across space and time [

6]. Activity-based indices summarize the portfolio of measures adopted by holdings using weighted checklists or counts [

7,

8]. While informative about what farmers do, these approaches mainly capture actions already implemented and tend to under-represent the intermediate intention-to-action stage that precedes adoption decisions, where many efforts stall due to perceived risk, complexity, or limited control [

9,

10,

11].

Behavioral frameworks help explain this gap. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) emphasizes perceived usefulness and ease of use as proximal drivers of intention for information-intensive practices and tools [

10]. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) integrates attitudes, perceived social norms, and perceived behavioral control, linking intentions with behavior under real-world constraints [

11]. Recent syntheses in agricultural adoption research underline that technology beliefs and situational factors jointly condition uptake, and that intention may be high even where implementation remains uneven [

7].

This paper addresses the measurement gap by proposing the Farmers’ Readiness for Climate Adaptation (FRCA)—a factor-analytic composite index that captures the intermediate stage between intention and implementation. FRCA consolidates three pillars: (i) technology acceptance (TAM: perceived usefulness, ease of use, intention), (ii) behavioral disposition (TPB: attitudes, perceived norms, perceived behavioral control), and (iii) contextual conditions encompassing the environmental, economic, and institutional aspects that shape feasibility and timing of adoption. Using validated multi-item Likert scales and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), reliability and validity (CR, AVE) were assessed, supporting a second-order structure that yields a single 0–100 score with decomposable sub-indices for diagnosis [

12,

13,

14].

FRCA was applied to a sample of farmers in Kilkis, Central Macedonia (Greece), comparing readiness patterns across locations and farm characteristics. Our contribution is twofold: (a) a transparent, psychometrically grounded readiness measure aligned with established behavioral theory, and (b) empirical evidence on where and why readiness is limited—whether due to technology perceptions, behavioral dispositions, or contextual conditions—to inform targeted, context-appropriate adaptation pathways. By focusing on readiness rather than realized actions, FRCA complements existing indices and offers a practical lens for prioritizing support and tracking progress over time.

2. Materials and Methods

A quantitative, cross-sectional survey was conducted in farming communities of Kilkis, Central Macedonia, Greece between April and August 2024. Data were collected through a structured questionnaire administered both online and in person with the aim of representing all the agricultural systems of the prefecture: the agricultural system of irrigated lands, the agricultural system of drylands and the agricultural system of viticulture. In total, 82 valid responses were obtained, covering farm decision-makers actively engaged in management.

The questionnaire comprised three sections: farmer profile, farm characteristics, and perceptions/practices related to climate adaptation. Items included both multiple-choice questions and Likert-scale statements (1–5) on usefulness, ease of use, resources, support, and norms [

15].

The Farmers’ Readiness for Climate Adaptation (FRCA) index was developed as a composite indicator capturing the intermediate stage between intention and action. It consolidated three pillars: technology acceptance (TAM: PU, PEOU) [

10], behavioral disposition (TPB: SN, PBC) [

11], and contextual conditions (environmental, economic, institutional). Subscales were normalized to 0–100 for comparability [

16]. The FRCA score for respondent

i is:

, with

and

. The score ranges from 0 to 100, where 0–33 = low readiness, 34–66 = moderate, and 67–100 = high readiness.

Data analysis was performed with Jamovi [

17] and R [

18] using descriptive statistics and confirmatory factor analysis, while Microsoft Excel [

19] supported visualization and tabular presentation.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

The final sample comprised N = 82 farmers from Kilkis, Central Macedonia. Most respondents were male, with the largest age group between 36 and 55 years. Educational attainment varied, with a notable share holding secondary education, while smaller proportions had tertiary education. Farm characteristics reflected the structure of the study areas: medium-sized holdings, predominance of arable crops (cereals, maize), and mixed systems in some cases. Average farm size was moderate, and the majority of respondents reported full-time involvement in farming activities.

3.2. Perceptions of Climate Change and Adaptation Practices

Respondents consistently perceived climate change as a serious threat to agricultural stability. Reported impacts included increased drought stress, irregular precipitation, and shifts in pest and disease pressure. Many farmers indicated awareness of recent extreme events (heatwaves, floods) that directly affected crop yields.

Adoption of adaptation measures was uneven. Some respondents reported water-saving practices, diversification of crop rotations, or adjustments in sowing dates, while others expressed willingness but cited financial and institutional constraints as barriers. Notably, social norms and peer practices appeared influential, as many respondents indicated that observing adoption by neighbors encouraged their own willingness to adjust.

3.3. FRCA Index Scores

The Farmers’ Readiness for Climate Adaptation (FRCA) Index was calculated using the methodology described in

Section 2. Subscales were normalized to 0–100 and aggregated through confirmatory factor analysis weights (

Table 1).

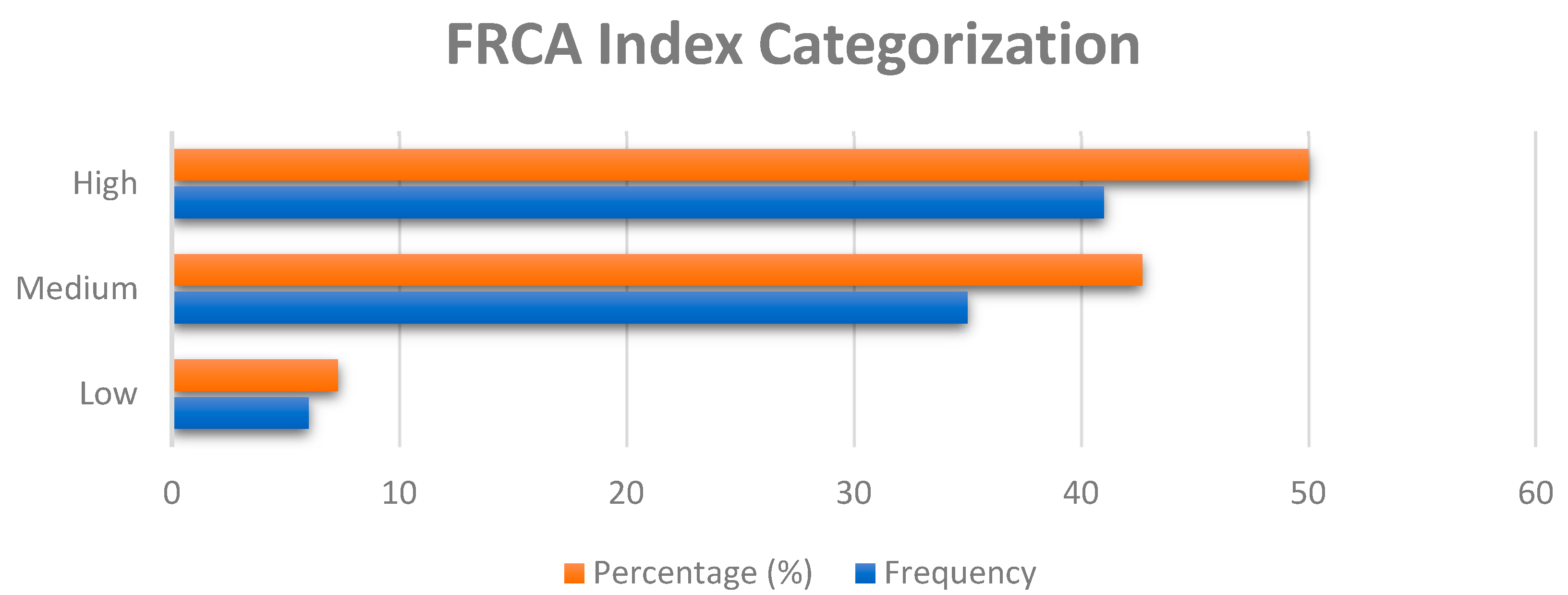

The overall FRCA index had a mean score in the mid-60s. The largest share of farmers fell into the high-readiness category (>67), followed by those with medium readiness (34–66). Only a small fraction remained at low readiness (<33), reflecting attitudinal, economic, or institutional barriers (

Figure 1).

Sub-index analysis revealed the following:

Technology acceptance (TAM) scores were generally above average, indicating that farmers perceive new and innovative practices as useful, though concerns about ease of use persisted.

Behavioral disposition (TPB) scores showed variation: attitudes toward adaptation were positive, but subjective norms and perceived control were weaker, suggesting that external constraints shape readiness.

Contextual conditions (environmental, economic, institutional) scored lowest, underscoring the limiting role of financial resources and institutional support.

3.4. Hypothesis Testing

The FRCA index was compared across demographic groups using t-tests and ANOVA, with significance set at

p < 0.05 [

14,

18]:

Farm size (H1): Farmers with smaller holdings (<5 ha) showed significantly higher readiness (M = 66.7, SD = 11.3) than those with larger farms (M = 59.8, SD = 18.3; p = 0.038).

Age (H2): Older farmers (≥50 years) scored higher (M = 65.7, SD = 13.2) than younger ones (M = 56.4, SD = 19.6; p = 0.025).

Income (H3): No significant difference was found between lower (<10,000 EUR) and higher income groups (p = 0.855).

Education (H4): Readiness did not vary across education levels, whether analyzed in five or two categories (p = 0.93; p = 0.72).

Overall, farm size and age significantly influenced FRCA, while income and education did not. These results suggest that readiness is shaped more by experience and flexibility than by financial or educational resources.

4. Discussion

This study introduced the FRCA index as a novel tool for assessing farmers’ readiness for climate adaptation, explicitly addressing the gap between intention and action. By combining constructs from TAM (perceived usefulness, ease of use) and TPB (social norms, perceived control) with contextual dimensions (environmental, economic, and institutional), the index captures the psychosocial and structural factors that shape adaptation decisions [

16,

17,

18].

The results demonstrated that readiness is multidimensional and heterogeneous across locations and farmer profiles. Age and farm size significantly differentiated FRCA scores, with older farmers and smaller holdings showing higher readiness. These findings highlight that adaptation is not determined solely by economic resources or education but by the interaction of experience, flexibility, and enabling conditions. Regional patterns also confirmed that local contexts matter: institutional support, social norms, and perceived feasibility influenced whether intentions could be translated into practice. These results align with previous studies documenting the central role of psychosocial and contextual factors in shaping adoption pathways [

7,

8,

9].

5. Conclusions

The FRCA index provides a structured and reliable framework for assessing readiness for climate adaptation, extending beyond conventional measures that focus only on vulnerability or realized actions. Its application in Central Macedonia revealed that adaptation readiness depends less on income or formal education and more on experience, farm structure, and contextual support.

Policy implications are clear. Strengthening advisory systems, reducing institutional barriers, and enhancing cooperative structures are crucial for enabling farmers to act on their intentions. Financial support mechanisms should be designed to address resource constraints, while information campaigns and training can help overcome negative social norms and increase perceived control. At the European level, the FRCA can also serve as a diagnostic tool for tailoring interventions within the framework of the Common Agricultural Policy.

Despite its contribution, the study has limitations, including a relatively small, non-random sample and reliance on self-reported data. Future research should test the FRCA in larger and more diverse samples, track readiness over time, and combine quantitative and qualitative approaches to better capture the drivers of adaptation. Nonetheless, the index offers a valuable basis for both scientific inquiry and policy design, supporting efforts to strengthen the resilience and sustainability of Mediterranean agriculture under climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.O., S.K. and G.K.; methodology, G.O.; software, G.O.; validation, S.K. and G.K.; formal analysis, G.O.; investigation, G.O.; resources, S.K. and G.K.; data curation, G.O., S.K. and G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.O.; writing—review and editing, G.O., S.K. and G.K.; visualization, G.O.; supervision, S.K. and G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the grant titled “Social transformation in the rural areas: profile, innovations and collective actions of farmers. The case of the Prefecture of Kilkis (Greece)” (Grant No. 81725), awarded by the Special Account for Research Funds of the International Hellenic University. It falls under task 2 of the program “Measures to Promote Research through Financial Support to Laboratories and Institutes of the International Hellenic University”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as no institutional review board was available at the time of data collection. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed about the purpose of the research and voluntarily agreed to participate. Anonymity and confidentiality were strictly maintained.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. To protect participants’ privacy, interview transcripts cannot be shared publicly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Iglesias, A.; Garrote, L.; Quiroga, S.; Moneo, M. A Regional Comparison of the Effects of Climate Change on Agricultural Crops in Europe. Clim. Chang. 2012, 112, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesk, C.; Rowhani, P.; Ramankutty, N. Influence of Extreme Weather Disasters on Global Crop Production. Nature 2016, 529, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Bobea, A.; Ault, T.R.; Carrillo, C.M.; Chambers, R.G.; Lobell, D.B. Anthropogenic Climate Change Has Slowed Global Agricultural Productivity Growth. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.B.; Riederer, A.M.; Foster, S.O. The Livelihood Vulnerability Index: A Pragmatic Approach to Assessing Risks from Climate Variability and Change—A Case Study in Mozambique. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Below, T.B.; Mutabazi, K.D.; Kirschke, D.; Franke, C.; Sieber, S.; Siebert, R.; Tscherning, K. Can Farmers’ Adaptation to Climate Change Be Explained by Socio-Economic Household-Level Variables? Glob. Environ. Change 2012, 22, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, U.; Wilson, C. Derivation of a Climate Change Adaptation Index at the Household Level and Its Application in Nepal. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 101, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopy, L.S.; Floress, K.; Arbuckle, J.G.; Church, S.P.; Eanes, F.R.; Gao, Y.; Gramig, B.M.; Ranjan, P.; Singh, A.S. Adoption of Agricultural Conservation Practices in the United States: Evidence from 35 Years of Quantitative Literature. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2019, 74, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Church, S.P.; Floress, K.; Prokopy, L.S. Synthesizing Conservation Motivations and Barriers: What Have We Learned from Qualitative Studies of Farmers’ Behaviors in the United States? Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 32, 1171–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C.; Ekstrom, J.A. A Framework to Diagnose Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22026–22031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. Tests of Significance in Factor Analysis. Br. J. Stat. Psychol. 1950, 3, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Andover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Nardo, M.; Saisana, M.; Saltelli, A.; Tarantola, S.; Hoffman, A.; Giovannini, E. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD Statistics Working Paper; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi (Version 2.3) [Computer Software]. 2023. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel (Version 16.0) [Computer Software]; Microsoft Corporation: Redmond, WA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |