Abstract

Medical images demand robust privacy protection, driving research into advanced image encryption (IE) schemes. However, current IE schemes still encounter certain challenges in both security and efficiency. Fractional-order Hopfield neural networks (HNNs) demonstrate unique advantages in IE. The introduction of fractional-order calculus operators enables them to possess more complex dynamical behaviors, creating more random and unpredictable keystreams. To enhance privacy protection, this paper introduces a high-performance medical IE scheme that integrates a novel 4D fractional-order HNN with a differentiated encryption strategy (MIES-FHNN-DE). Specifically, MIES-FHNN-DE leverages this 4D fractional-order HNN alongside a 2D hyperchaotic map to generate keystreams collaboratively. This design not only capitalizes on the 4D fractional-order HNN’s intricate dynamics but also sidesteps the efficiency constraints of recent IE schemes. Moreover, MIES-FHNN-DE boosts encryption efficiency through pixel bit splitting and weighted accumulation, ensuring robust security. Rigorous evaluations confirm that MIES-FHNN-DE delivers cutting-edge security performance. It features a large key space (), exceptional key sensitivity, extremely low ciphertext pixel correlations (<0.002), excellent ciphertext entropy values (>7.999 bits), uniform ciphertext pixel distributions, outstanding resistance to differential attacks (with average NPCR and UACI values of and , respectively), and remarkable robustness against data loss. Most importantly, MIES-FHNN-DE achieves an average encryption rate as high as 102.5623 Mbps. Compared with recent leading counterparts, MIES-FHNN-DE better meets the privacy protection demands for medical images in emerging fields like medical intelligent analysis and medical cloud services.

1. Introduction

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are sophisticated computational models that mimic the information-processing architecture of the human brain, operating as nonlinear dynamical systems [1,2,3,4]. Among the diverse array of ANNs, Hopfield neural networks (HNNs) stand out as well-developed feedback-type neural networks [5]. Currently, HNNs have found widespread applications across multiple fields. These include associative memory systems [6], optimization problem-solving [7], information security [8,9,10], and image processing [11,12].

The nonlinearity of HNNs stems from the nonlinear activation functions interconnecting the neurons [13]. This nonlinear behavior makes HNNs similar to chaotic systems, exhibiting complex dynamic behaviors, including chaotic and hyperchaotic states [14]. By leveraging the nonlinear and chaotic properties of HNNs, secure image encryption (IE) schemes can be devised, protecting sensitive visual data from unauthorized access. Compared with integer-order HNNs, fractional-order HNNs exhibit unique advantages in IE [15]. The integration of fractional-order calculus operators grants them more diverse and complex dynamic characteristics, enabling the generation of keystreams with higher randomness and unpredictability. This effectively improves the attack resistance capability of IE schemes and offers a higher level of security protection for image data [15,16].

Medical images serve as crucial evidence for disease diagnosis, treatment, and medical research. The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud technologies has spurred a surge in emerging medical image applications [17]. Medical images typically contain sensitive privacy information, and their leakage can lead to severe consequences in terms of medical security or fraud. Thus, providing more secure and efficient protection for medical images has become a major research focus [18]. IE transforms medical images into indistinguishable ciphertext form, effectively thwarting external illegal theft and tampering and ensuring the security of their transmission and storage [19]. Recently, an increasing number of researchers have been committed to achieving secure and efficient medical IE by introducing various new technologies, including fractional-order HNNs, to effectively protect the patients’ privacy information [14,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Leng et al. [14] constructed three memristive HNNs exhibiting multiple controllable nonlinear offset behaviors, demonstrating rich dynamical characteristics crucial for secure communication applications. Then, they proposed a medical IE scheme based on the HNNs and a scrambling-diffusion structure. Because the encryption steps of their scheme are relatively simple and the encryption keystreams are completely unrelated to the plaintext, their scheme can actually be easily cracked by chosen plaintext attacks. Leveraging a 2D hyperchaotic map, Zhang et al. [17] constructed a secure IE scheme to protect patient privacy. Their scheme employed dynamic Josephus scrambling and parallel cross-diffusion to disrupt pixel correlations and diffuse pixels. Notably, their scheme directly uses hash values to update the secret key, which introduces practical issues related to key management. In addition, due to the relatively simple encryption steps and key update mechanism, their scheme can also be cracked through chosen plaintext attacks. Sun et al. [19] presented a memristive HNN with four neurons and utilized it to devise a medical IE scheme. Due to its exclusive reliance on the HNN for keystream generation, the scheme suffers from low encryption efficiency, taking as long as 3.9 s to encrypt a medical image of pixels. Exploiting compressed sensing and a 4D hyperchaotic map, Lai et al. [22] proposed an IE scheme aiming to achieve high security and efficiency in medical image transmission. Their scheme directly employs the image hash value as the secret key, bringing key management challenges. Moreover, the encryption rate of this scheme is low, measuring just 8.6038 Mbps. Jiang et al. [25] first constructed a fractional-order HNN with rich dynamics and subsequently proposed a medical IE scheme based on compressed sensing and singular value decomposition. Despite achieving satisfactory security, the scheme’s exclusive reliance on the fractional-order HNN for chaotic sequence generation and its complex encryption structure make it inefficient for practical medical applications.

Through comprehensive analysis combined with previous cryptanalysis efforts, we discovered that current medical IE schemes still fall short in meeting the demands of medical applications [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Many schemes directly employ image hash values to generate keystreams, resulting in practical issues with key management. Moreover, due to design issues, the vast majority of existing schemes either have insufficient encryption efficiency or security flaws. Therefore, to address these issues, we have devised a high-performance medical IE scheme that integrates a novel 4D fractional-order HNN with a differentiated encryption strategy (MIES-FHNN-DE). Our MIES-FHNN-DE method boasts multiple tailored and novel designs. Firstly, MIES-FHNN-DE avoids relying on image hash values for keystream generation, thus sidestepping practicality issues related to key management. Secondly, MIES-FHNN-DE solely taps into the fractional-order HNN’s complex structure to generate a portion of the chaotic sequences, exploiting its superior chaotic performance while overcoming efficiency constraints. Thirdly, MIES-FHNN-DE employs a meticulously engineered differentiated encryption framework based on pixel bit splitting and weighted accumulation, dramatically boosting encryption efficiency. Finally, MIES-FHNN-DE carries out pixel diffusion, permutation, and substitution through vector-level dynamic partitioning operations, perfectly balancing high security and efficiency. Overall, the principal contributions of this paper include:

- By leveraging a novel 4D fractional-order HNN with remarkable chaotic performance, we propose a high-performance medical IE scheme named MIES-FHNN-DE. The proposed MIES-FHNN-DE approach addresses the shortcomings of existing schemes, offering enhanced privacy protection for medical images.

- MIES-FHNN-DE creatively combines a 4D fractional-order HNN with a 2D discrete hyperchaotic map to collaboratively generate chaotic sequences. While exploiting the 4D fractional-order HNN’s superior chaotic performance, this design effectively overcomes the efficiency issues that undermine existing schemes.

- MIES-FHNN-DE employs the secret key to generate chaotic sequences and only utilizes hash values to control keystream transformation. Most existing medical IE schemes directly use hash values for chaotic sequence generation, which leads to significant issues with key management and the reusability of sequences. Our design effectively addresses these issues.

- MIES-FHNN-DE presents a novel plaintext-dependent dynamic partitioning mechanism and applies efficient vector-level operations in the diffusion, scrambling, and substitution steps of the encryption process. This innovative design not only introduces plaintext-related dynamics but also achieves outstanding encryption efficiency that far surpasses existing schemes.

- Our in-depth evaluation and comparative study demonstrate that MIES-FHNN-DE offers a formidable combination of outstanding security and efficiency. Its ultra-high encryption rate far exceeds the latest IE schemes, making it a superior choice for diverse emerging medical applications.

Moving forward, Section 2 will introduce the theoretical foundations of fractional-order calculus, HNNs, and the 4D fractional-order HNN adopted in this study. Section 3 will systematically elaborate our meticulously designed MIES-FHNN-DE approach. In Section 4, we present the security and efficiency evaluations of MIES-FHNN-DE, along with comparative analyses. Finally, Section 5 summarizes this paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Fractional-Order Calculus and 4D Fractional-Order HNN

In this section, we provide a concise overview of the theoretical underpinnings related to fractional-order calculus, HNNs, and 4D fractional-order HNN employed in our MIES-FHNN-DE approach. We emphasize the applicability of fractional-order calculus to our specific research context and clarify the necessary assumptions for its application in our medical IE scheme.

2.1. Fractional-Order Calculus

Fractional-order calculus generalizes classical integer-order differentiation/integration to arbitrary non-integer orders, providing superior modeling capabilities for systems with memory effects and spatial heterogeneity [6,16,32]. This subsection presents the fundamental definitions and analytical properties of fractional-order calculus that are essential for understanding the dynamics of fractional-order neural networks, with a particular focus on their applicability to our medical IE scheme.

The Caputo fractional derivative is a fundamental concept in fractional-order calculus, especially valuable for regularizing initial conditions in Cauchy problems. A Cauchy problem typically involves finding a solution to a differential equation that satisfies given initial conditions. The Caputo fractional derivative extends the classical notion of differentiation to non-integer orders, enabling the modeling of systems with memory effects and long-range dependencies. The Caputo fractional derivative is defined as

where:

- : The Caputo fractional derivative operator. The subscript a is the lower limit of integration, the superscript C denotes “Caputo”, and is the non-integer order of the derivative.

- : The function for which the fractional derivative is being calculated, with t as the independent variable.

- : A normalization constant. is the Euler gamma function, and n is an integer such that .

- : The definite integral with respect to from a to t, used to combine the contributions of the function and its derivatives over the interval.

- : The kernel of the integral, a power function of with exponent , determining the weighting of the contributions.

- : The n-th derivative of with respect to , where n is related to the order of the fractional derivative.

- : The differential of the integration variable .

In our application, to ensure the system remains in a chaotic state necessary for generating keystreams in our encryption scheme, we dynamically set the fractional order q within the range , as determined by dynamical analysis in [32]. Initial conditions for the Cauchy problems are meticulously chosen within a small neighborhood of the origin to guarantee the regularity and well-posedness of the solutions, ensuring the system starts in a stable region before transitioning to chaos. We employ the improved Euler method with a step size of to approximate the solutions of the fractional-order differential equations, balancing accuracy and computational efficiency due to the absence of analytical solutions for most practical systems. The synaptic weight parameters are fixed at and to achieve the desired chaotic dynamics, with the fractional order q dynamically adjusted within the specified range to sustain the chaotic behavior. Additionally, we discard the first of the generated sequence to eliminate transient effects, ensuring the remaining sequence is in a steady chaotic state.

2.2. Hopfield Neural Networks

HNNs constitute a fundamental class of recurrent neural networks exhibiting content-addressable memory through symmetric weight interconnections [33,34]. This subsection establishes their mathematical foundation and dynamic principles. Consider an HNN with n neurons where the state vector evolves according to:

where denotes the symmetric weight matrix (), are threshold parameters, and is the sign function.

For continuous-time formulations, the dynamics are governed by:

where controls the network’s sensitivity.

2.3. The 4D Fractional-Order HNN

The Hopfield model, as a paradigmatic recurrent neural network, replicates neuronal interconnections to enable efficient information storage and retrieval. The network consists of mutually connected neurons, whose states are determined by input stimuli and internal dynamics, followed by nonlinear activation. Recently, Ma et al. [32] constructed a 4D fractional-order HNN by incorporating fractional-order calculus into the HNN framework, as described by Equations (1)–(3). This system’s pronounced sensitivity to initial conditions and intricate dynamics make it particularly suitable for generating keystreams in image encryption (IE) applications.

The 4D fractional-order HNN is described by the following set of differential equations:

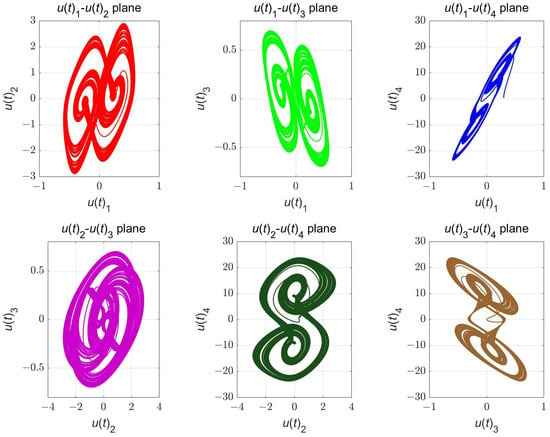

where denotes the Caputo fractional-order derivative, the fractional order q is greater than 0 and less than 1, and are four state variables. Additionally, and are synaptic weight parameters. This 4D fractional-order HNN exhibits chaotic behavior for , , and , as confirmed by dynamical analysis in [32] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Six attractors of the 4D fractional-order HNN generated under , , and .

To numerically solve the fractional-order differential equations presented in Equation (4), we employ the improved Euler method, a numerical technique well suited for systems lacking analytical solutions. The fractional order q, which plays a crucial role in determining the system’s dynamics, is dynamically adjusted within the range . In our MATLAB implementation, we set a step size to balance computational efficiency and accuracy. During the simulation, we discard the first of the generated sequence to eliminate transient effects, ensuring that the remaining sequence is in a steady chaotic state, which is vital for the encryption process.

The chaotic behavior exhibited by the 4D fractional-order HNN is harnessed in our medical IE scheme to generate keystreams that are highly sensitive to initial conditions and system parameters. Specifically, the synaptic weight parameters and are set to 0.4 and 12, respectively, based on empirical testing and dynamical analysis to ensure the desired chaotic dynamics. These parameters, along with the dynamically adjusted fractional order q, contribute to the system’s sensitivity and unpredictability. By exploiting these chaotic properties, our encryption scheme generates keystreams that are extremely difficult to predict or replicate without precise knowledge of the initial conditions and parameters. This high level of sensitivity enhances the security of our scheme, making it robust against various cryptographic attacks.

3. Proposed MIES-FHNN-DE

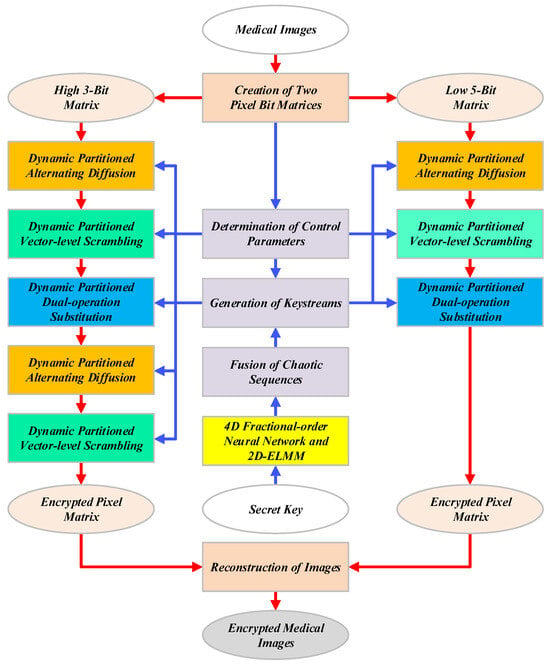

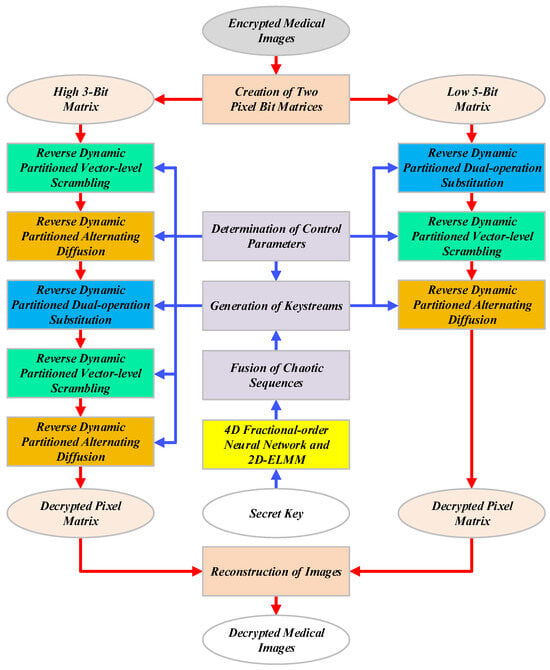

This section elaborates on our proposed MIES-FHNN-DE method, which integrates the 4D fractional-order HNN with differentiated encryption. The encryption process of MIES-FHNN-DE includes seven distinct steps (see Figure 2), each of which will be systematically described hereafter. To better focus on addressing the efficiency and security issues in existing medical IE schemes by leveraging the 4D fractional-order HNN and differentiated encryption strategy, our MIES-FHNN-DE approach is applied under the following assumptions and conditions: (1) the medical images input into MIES-FHNN-DE for encryption each time are multiple 8-bit grayscale images or 24-bit RGB color images of the same size; and (2) the width and height of the medical images to be encrypted are both multiples of 4.

Figure 2.

Encryption process of MIES-FHNN-DE.

3.1. Fusion of Chaotic Sequences

To avoid the practicality issues associated with secret key designs in existing IE schemes, the MIES-FHNN-DE model employs a different secret key design and keystream generation approach. Initially, MIES-FHNN-DE abstains from directly using plaintext-dependent data to drive the 4D fractional-order HNN and 2D-ELMM [35] for chaotic sequence generation. Subsequently, the reusable chaotic sequences, linked with the secret key, are converted into keystreams tailored for encrypting distinct input images. Our design not only avoids the dilemma of key management but also ensures plaintext dependency of the keystreams.

Driven by the secret key , the “Fusion of Chaotic Sequences” of MIES-FHNN-DE will be executed as follows:

- Step 1: Input the first five components of K into the 4D fractional-order HNN to generate a chaotic sequence of length . Note that represents the size of the medical images to be encrypted, and denotes the number of these images (or image channels).

- Step 2: Initialize a sequence of length where all elements are zero, and let .

- Step 3: Create a 2D matrix by executing matrix multiplication on the remaining elements of . Specifically, .

- Step 4: Reshape into a 1D vector and let .

- Step 5: Input the last four components () of K into 2D-ELMM to obtain a chaotic sequence of length .

- Step 6: Perform vector addition on and to finalize the fusion of the chaotic sequences produced by the 4D fractional-order HNN and 2D-ELMM: .

3.2. Creation of Two Pixel Bit Matrices

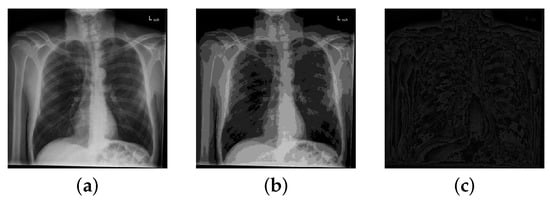

For medical images, the high 3-bit (H3B) part of each pixel contains the majority of visual information (see Figure 3). To enhance encryption efficiency, our MIES-FHNN-DE method adopts a differentiated encryption strategy for input medical images. Specifically, the H3B parts of input pixels are subjected to high-intensity encryption, while the low 5-bit (L5B) parts undergo relatively weaker encryption to achieve higher encryption efficiency.

Figure 3.

Visual representation of the H3B part and L5B part of a medical image: (a) original CT chest image; (b) H3B part of CT chest image; (c) L5B part of CT chest image.

The “Creation of Two Pixel Bit Matrices” of MIES-FHNN-DE splits all input pixels into their H3B and L5B parts, followed by weighted accumulation to create two pixel matrices and for subsequent differentiated encryption. For the 3D pixel matrix of size and composed of input medical images, the specific processing steps are:

- Step 1: Reshape into a 4D pixel matrix of size . Note that , , represents the size of the medical images, and denotes the number of these images (or image channels). Let extract the H3B part of each pixel in .

- Step 2: Initialize a 3D pixel matrix of size with all elements set to zero. This matrix will be used to store the weighted accumulation results of the pixel H3B parts.

- Step 3: Conduct weighted accumulation over the fourth dimension of , indexed by i (), and let .

- Step 4: Let , and then reshape into the 2D H3B pixel matrix of size .

- Step 5: Reshape into a 4D pixel matrix of size , and let to extract the L5B part of each pixel in .

- Step 6: Initialize a 3D pixel matrix of size with all elements set to zero. This matrix will be used to store the weighted accumulation results of the pixel L5B parts.

- Step 7: Conduct weighted accumulation over the 4th dimension of , indexed by j (), and let .

- Step 8: Let , and then reshape into the 2D L5B pixel matrix of size .

3.3. Determination of Control Parameters

To enhance plaintext dependency and introduce dynamics into the encryption process, MIES-FHNN-DE utilizes the SHA-256 hash values derived from the pixel matrices and to determine three plaintext-dependent dynamic parameters. These parameters will be employed in subsequent encryption steps to strengthen the overall security of MIES-FHNN-DE. The following outlines the computational procedure for determining these three parameters:

- Step 1: Perform a modular addition operation in vector form to integrate the hash value of and the hash value of into a hash value byte vector of length 32: .

- Step 2: Initialize a zero-valued variable , which will be employed to accumulate the results of subsequent operations.

- Step 3: Employ as the index to perform four rounds of successive multiplication and accumulation operations on the 32 byte elements of :

- Step 4: Perform modular addition operations on to produce three dynamic control parameters , , and that will be used in the subsequent encryption procedures. Specifically, , , and .

3.4. Generation of Keystreams

To achieve higher plaintext sensitivity and ensure the reusability of chaotic sequences, our MIES-FHNN-DE method further transforms the fused chaotic sequence (generated using the secret key K; see Section 3.1) into the keystreams tailored for encrypting the two pixel matrices and (generated from input medical images; see Section 3.2). Specifically, the “Generation of Keystreams” of MIES-FHNN-DE transforms into the keystreams , , , , and as follows:

- Step 1: Perform a truncation operation on by redefining it as , thereby discarding the first elements.

- Step 2: Set . Here, , and the keystream will be used in the first round of vector-level scrambling operations for the H3B pixel matrix .

- Step 3: Set . The keystream will be used in the second round of vector-level scrambling operations for .

- Step 4: Set . The keystream will be used in the vector-level scrambling operations for the L5B pixel matrix .

- Step 5: Set and then reshape into a 2D form of size . Here, means rounding the operand down, and the keystream will be used in the diffusion and substitution operations for .

- Step 6: Set and then reshape into a 2D form of size . The keystream will be used in the diffusion and substitution operations for .

3.5. Dynamic Partitioned Alternating Diffusion

To boost encryption efficiency and security, the “Dynamic Partitioned Alternating Diffusion” of MIES-FHNN-DE achieves plaintext-dependent vector-level diffusion operations via dynamic partitioning. Our MIES-FHNN-DE method will execute two rounds of diffusion processing on the H3B pixel matrix and one round of diffusion processing on the L5B pixel matrix . Because there is no substantial difference among these diffusion steps, this paper only describes the first round of diffusion processing for . For the input of size , MIES-FHNN-DE diffuses it via the following process:

- Step 1: Initialize two zero-valued intermediate ciphertext matrices, and , of identical size to , and then determine the first two partitioning indices:

- Step 2: Perform an XOR-based diffusion operation on the first row of . Specifically, .

- Step 3: For each integer , perform a modular addition diffusion operation on the i-th row of . Specifically, .

- Step 4: For each integer , perform an XOR-based diffusion operation on the j-th row of . Specifically, .

- Step 5: For each integer , perform a modular addition diffusion operation on the k-th row of . Specifically, .

- Step 6: Determine the last two partitioning indices:

- Step 7: Perform an XOR-based diffusion operation on the first column of . Specifically, .

- Step 8: For each integer , perform a modular addition diffusion operation on the i-th column of . Specifically, .

- Step 9: For each integer , perform an XOR-based diffusion operation on the j-th column of . Specifically, .

- Step 10: For each integer , perform a modular addition diffusion on the k-th row of . Specifically, .

3.6. Dynamic Partitioned Vector-Level Scrambling

Driven by the dynamic control parameters and keystreams, the “Dynamic Partitioned Vector-level Scrambling” of MIES-FHNN-DE realizes plaintext-dependent vector-level quick scrambling through dynamic partitioning. In our MIES-FHNN-DE method, a total of three rounds of vector-level scrambling will be performed. Given that these scrambling operations have no substantial difference, this paper only describes the scrambling process of the H3B intermediate ciphertext matrix in detail. For the input of size , MIES-FHNN-DE scrambles it via the following process:

- Step 1: Initialize two zero-valued intermediate ciphertext matrices, and , of identical size to , and then determine the first two partitioning indices:

- Step 2: Sort the first elements of the keystream to obtain the scrambling index vector . Then, perform quick row scrambling on the first columns of with :

- Step 3: Sort the next elements of to obtain the scrambling index vector . Then, perform quick row scrambling on the columns to of with :

- Step 4: Sort the next elements of to obtain the scrambling index vector . Then, perform quick row scrambling on the columns to of with :

- Step 5: Determine the last two partitioning indices:

- Step 6: Sort the next elements of to obtain the scrambling index vector . Then, perform quick column scrambling on the first rows of with :

- Step 7: Sort the next elements of to obtain the scrambling index vector . Then, perform quick column scrambling on the rows to of with :

- Step 8: Sort the last elements of to obtain the scrambling index vector . Then, perform quick column scrambling on the rows to of with :

3.7. Dynamic Partitioned Dual-Operation Substitution

To further enhance security and improve encryption efficiency, the “Dynamic Partitioned Dual-operation Substitution” of MIES-FHNN-DE leverages dynamic partitioning to achieve plaintext-dependent partition-level substitution operations. Specifically, our proposed MIES-FHNN-DE method will perform one round of dual-operation substitution processing on the H3B and L5B parts of the input medical images, respectively. Because these substitution operations are similar, we only describe the substitution processing of the H3B intermediate ciphertext pixel matrix in detail. For the input of size , MIES-FHNN-DE substitutes it via the following process:

- Step 1: Initialize one zero-valued intermediate ciphertext matrix of identical size to , and then determine the two partitioning indices:

- Step 2: Apply modular addition substitution to the first columns of using the keystream . Namely, .

- Step 3: Perform XOR substitution on the columns to of with . Specifically, .

- Step 4: Apply modular addition substitution on the columns to of using . Namely, .

3.8. Complete Process of MIES-FHNN-DE

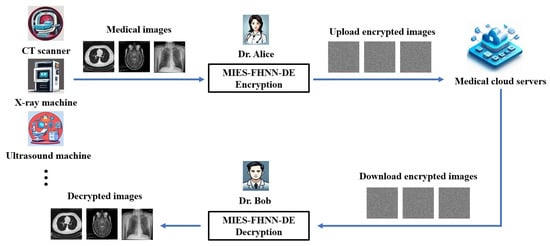

This subsection briefly outlines the complete encryption process for MIES-FHNN-DE within the context of a real-world deployment scenario, clarifying the sequential order of execution for all steps, as well as their respective inputs and outputs.

As shown in Figure 4, Suppose Dr. Alice intends to upload patients’ medical images to cloud servers for healthcare collaboration or patient access. To safeguard patient privacy, she employs MIES-FHNN-DE to encrypt these images:

Figure 4.

A real-world deployment scenario of MIES-FHNN-DE.

- Step 1: Input the nine components of the secret key K into the 4D fractional-order HNN and 2D-ELMM based on the size and quantity of the medical images requiring encryption. Generate the chaotic sequences and . Transform into and fuse it with to obtain the fused chaotic sequence . For more details, see Section 3.1.

- Step 2: Perform splitting and weighted accumulation operations on the 3D pixel matrix composed of the input images to obtain the 2D pixel matrices and . Here, corresponds to the H3B parts of all pixels, while corresponds to the L5B parts. For more details, see Section 3.2.

- Step 3: Generate three dynamic control parameters , , and using the hash values and of and . For more details, see Section 3.3.

- Step 4: Generate the keystreams , , , , and from for encrypting and by applying . For more details, see Section 3.4.

- Step 5: Perform the “Dynamic Partitioned Alternating Diffusion” on the H3B pixel matrix with and , resulting in the intermediate ciphertext matrix . For more details, see Section 3.5.

- Step 6: Apply the “Dynamic Partitioned Vector-level Scrambling” on using and to obtain the intermediate ciphertext matrix . For more details, see Section 3.6.

- Step 7: Execute the “Dynamic Partitioned Dual-operation Substitution” on with and to obtain the intermediate ciphertext matrix . For more details, see Section 3.7.

- Step 8: Perform the second round of alternating diffusion on with and to obtain the intermediate ciphertext matrix .

- Step 9: Apply the second round of vector-level scrambling on using and to obtain the intermediate ciphertext matrix .

- Step 10: Perform one round of alternating diffusion on the L5B pixel matrix with and to obtain the intermediate ciphertext matrix .

- Step 11: Apply one round of vector-level scrambling on using and to obtain the intermediate ciphertext matrix .

- Step 12: Execute one round of dual-operation substitution on with and to obtain the intermediate ciphertext matrix .

- Step 13: Transform and into the final encrypted medical images via “Reconstruction of Images” (the mirror inverse step of “Creation of Two Pixel Bit Matrices”).

Subsequently, Dr. Alice uploads the encrypted medical images along with their associated hash values to the cloud servers. Other medical professionals (such as Dr. Bob in Figure 4) or patients who require access to the original medical images can decrypt these encrypted medical images using the secret key K, as illustrated in Figure 5. As all operations in the decryption process are the mirror inverses of those in the encryption process, detailed descriptions are omitted here.

Figure 5.

Decryption process of MIES-FHNN-DE.

4. Security and Efficiency Evaluations

We systematically evaluated the security and efficiency of MIES-FHNN-DE using a microcomputer running MATLAB R2017a, equipped with an Intel E3-1231 quad-core, eight-thread 3.40 GHz processor and 8 GB of memory. All experimental images were downloaded via hyperlinks from the NYU Health Sciences Library website (https://hslguides.med.nyu.edu/medicalimages, accessed on 16 May 2025). For standardized tests and comparisons, the downloaded medical images were resized to three common resolutions: , , and . Additionally, secret keys randomly selected from the key space were used to conduct the experiments, ensuring the generality and objectivity of our evaluations.

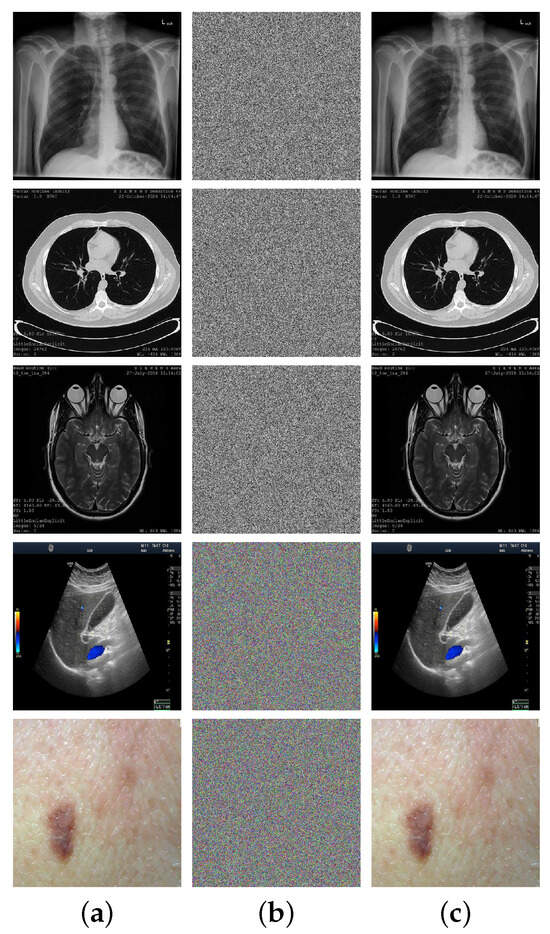

4.1. Visual Evaluation

To demonstrate superior protection capabilities for sensitive medical images, we applied MIES-FHNN-DE to five medical images (X-ray chest, CT chest, MRI head, US abdomen, and skin scar) common in clinical diagnosis. As seen (Figure 6), the MIES-FHNN-DE method successfully transformed five input images into noise-like ones, demonstrating strong protection capabilities. Meanwhile, the decrypted output perfectly restores all original details without any visual distortion or information loss. These results confirm that MIES-FHNN-DE not only ensures effective privacy protection but also guarantees lossless reversibility, making it well suited for various medical applications.

Figure 6.

Visual evaluations for MIES-FHNN-DE: (a) five medical images (X-ray chest, CT chest, MRI head, US abdomen, and skin scar); (b) encrypted output of (a); (c) decrypted output of (b).

4.2. Key Space

Brute-force attacks are based on exhaustive searches on key spaces. Thus, to resist such attacks, sufficiently large key spaces are essential. According to widely accepted standards, a secure IE scheme must provide a key space of at least [36]. If this criterion is not met, the scheme would be vulnerable to brute-force attacks, thereby compromising its overall security. The secret key of MIES-FHNN-DE is composed of nine components: , , , , , , , , and . In our MIES-FHNN-DE approach, these key components are all specified with a resolution of . Under these conditions, the key space size of MIES-FHNN-DE can be derived:

Evidently, far exceeds the suggested threshold of . This guarantees that our MIES-FHNN-DE method achieves provable resistance against brute-force attacks.

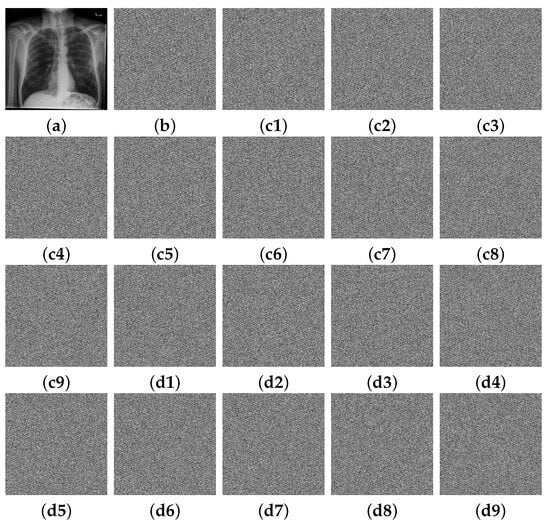

4.3. Key Sensitivity

Key sensitivity serves as a fundamental metric for cryptosystem evaluation. An ideal IE scheme must demonstrate high key sensitivity, wherein minimal key perturbations generate significant ciphertext deviations [37,38]. This property inherently satisfies the strict avalanche criterion (SAC), providing provable resistance against both brute-force and differential attacks. Our MIES-FHNN-DE approach was rigorously evaluated through component-wise perturbation analysis, with results being presented in Figure 7. As shown, for each component, a minimal perturbation () causes a significant ciphertext deviation. The magnitudes of the calculated ciphertext differences are substantial. Thus, our MIES-FHNN-DE approach possesses excellent key sensitivity.

Figure 7.

Component-wise perturbation analysis for MIES-FHNN-DE: (a) X-ray chest; (b) encrypted output of (a); (c1–c9) encryption outputs when each key component is incremented by ; (d1–d9) differences of (c1–c9) between (b).

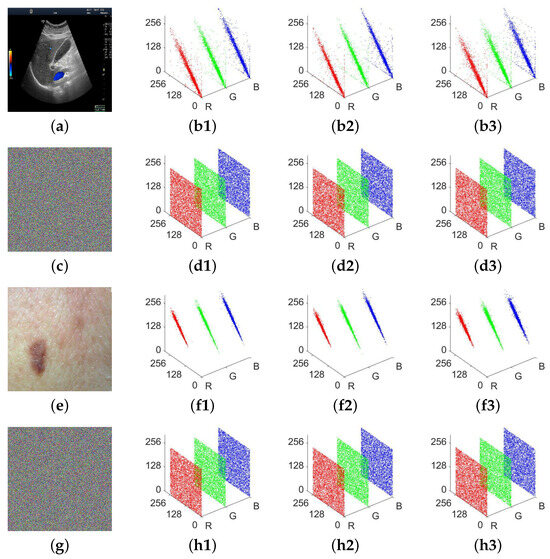

4.4. Pixel Correlation

Local strong spatial correlations are prominent features of medical images. When encryption fails to eliminate these statistical patterns, attackers could potentially reconstruct sensitive privacy data via cryptanalysis approaches that rely on pixel correlations [39]. Thus, we evaluated the spatial correlations of MIES-FHNN-DE’s ciphertext outputs using correlation distribution plots (see Figure 8). As seen, two input medical images possess notably high correlations between adjacent pixels in each of the three directions. Conversely, in the output encrypted images from MIES-FHNN-DE, these significant spatial correlations have been almost entirely eradicated.

Figure 8.

Correlation analysis for MIES-FHNN-DE: (a) US abdomen; (b1–b3) three subplots visualizing US abdomen’s pixel correlations across three spatial orientations (horizontal, vertical, and diagonal); (c) ciphertext of US abdomen; (d1–d3) three pixel correlation plots of (c); (e) skin scar; (f1–f3) three pixel correlation plots of (c); (g) ciphertext of skin scar; (h1–h3) three pixel correlation plots of (g).

Beyond the above graphical analysis, we quantitatively evaluated MIES-FHNN-DE with correlation coefficients (CCs) [40]. For two variables U and V (i.e., pixel values of adjacent pixel pairs), the is calculated as:

where and denote the values of adjacent pixel pairs, and represent the means of U and V, and Q is the quantity of pixel pairs. The ranges from −1 to 1, where indicates strong inter-pixel correlation and suggests statistical independence. For encrypted images, an ideal CC approaching 0 demonstrates successful disruption of spatial correlations. Table 1 reveals high CC values (>0.865) in all six medical images, whereas MIES-FHNN-DE’s ciphertext outputs show near-zero CC values (<0.002). Thus, MIES-FHNN-DE can successfully disrupt spatial relationships between adjacent pixels, defeating potential correlation-dependent attacks.

Table 1.

Absolute CC values for four grayscale and two color medical images with their ciphertexts.

4.5. Entropy Analysis

The uncertainty or randomness of ciphertexts can be gauged by information entropy, a fundamental concept underlying secure encryption. Generally, encrypted images with high entropy values (around bits) offer greater resistance to statistical attacks [41]. Given a discrete variable X representing the pixel values of an image, which can take values with corresponding probabilities , the information entropy is

Here, represents the base-2 logarithm, yielding entropy in bits. The entropy satisfies , where n is the total number of possible pixel values. For common 8-bit medical images, , resulting in a maximum entropy of bits.

With the above definition, we computed the entropy values for the ciphertext outputs of MIES-FHNN-DE (see Table 2). As shown, input medical images exhibit low entropy values due to inherent semantic patterns. Contrastingly, the output ciphertexts of MIES-FHNN-DE consistently approach the theoretical entropy ceiling. This statistical transformation confirms the excellence of MIES-FHNN-DE in producing outputs that are secure against entropy-based attacks.

Table 2.

Entropy values for four grayscale and two color medical images with their ciphertexts.

4.6. Pixel Distribution

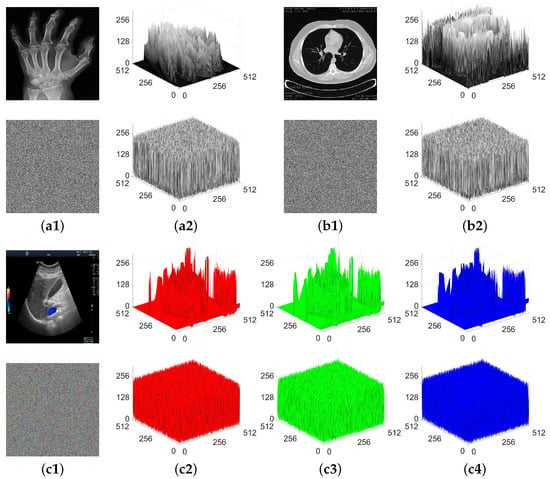

The homogenization of spatial frequency patterns constitutes an essential requirement for robust medical IE. Clinical imaging modalities (Figure 9) exhibit prominent distribution statistical signatures that an IE scheme must comprehensively obliterate, generating ciphertext outputs with highly homogeneous distributions [42]. As observed from Figure 9, the pixel distributions depicted in the subplots of the first and third rows are notably uneven. Conversely, after the encryption transformations of MIES-FHNN-DE, these prominent distribution characteristics are entirely eradicated. This indicates that, in the context of cryptanalysis related to pixel distributions, MIES-FHNN-DE is capable of providing reliable protection for various medical images.

Figure 9.

Pixel distribution analysis for MIES-FHNN-DE: (a1) X-ray hand and its ciphertext; (a2) 3D pixel distribution plots of (a1); (b1) CT chest and its ciphertext; (b2) 3D pixel distribution plots of (b1); (c1) US abdomen and its ciphertext; (c2) pixel distribution plots for the red channel; (c3) pixel distribution plots for the green channel; (c4) pixel distribution plots for the blue channel.

4.7. Differential Attacks

Generally, differential resistance ensures that the cryptosystem’s deterministic operations do not generate exploitable patterns [43]. This evaluation is particularly crucial for real-time IE schemes, where computational limitations may necessitate security compromises. Demonstrated differential immunity thus becomes a mandatory requirement for deployment in IoT- or cloud-based medical image applications.

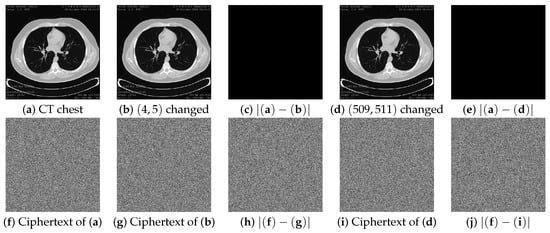

To provide a visual validation of MIES-FHNN-DE’s efficacy in countering differential cryptanalysis, we perturbed two separate bits in the CT chest image and calculated the ciphertext differential images. As observed (Figure 10), MIES-FHNN-DE exhibits strong diffusion capability and plaintext sensitivity, where minimal single-bit perturbations in plaintext inputs induce comprehensive ciphertext changes, verifying its remarkable strength against differential attacks.

Figure 10.

Visual evaluations on MIES-FHNN-DE for differential attacks: (a) original CT chest; (b) the least significant pixel bit located at is changed; (c) variance between (a) and (b); (d) the pixel bit at (509, 511) is changed; (e) variance between (a) and (d); (f) encrypted image of (a); (g) encrypted image of (b); (h) variance between (f) and (g); (i) encrypted image of (d); (j) variance between (f) and (i).

Furthermore, the diffusion capability of MIES-FHNN-DE was rigorously characterized through two complementary metrics: NPCR captures the spatial propagation rates of single-bit changes, whereas UACI provides normalized measurements of the average variation intensity across ciphertext outputs. Let I and be two ciphertext images of size ; the definition of NPCR is

Similarly, one can calculate the UACI value with

where and denote the pixel values at position . Table 3 presents the quantitative evaluation results of ciphertext pixel changes for MIES-FHNN-DE under single-bit changes. Observably, the average change rate of MIES-FHNN-DE closely approaches the optimal value of 99.6094%. Meanwhile, the average change intensity also approximates the optimal value of 33.4635%.

Table 3.

Quantitative evaluation results of ciphertext pixel changes for MIES-FHNN-DE.

4.8. Robustness Evaluation

In cloud-based applications such as distributed storage systems and computational platforms, encrypted medical imaging data remain vulnerable to partial degradation or information loss due to noise interference during transmission and processing. Thus, a viable encryption protection scheme should show sufficient robustness to enable the suitable reconstruction of the original medical images from damaged ciphertexts [44,45].

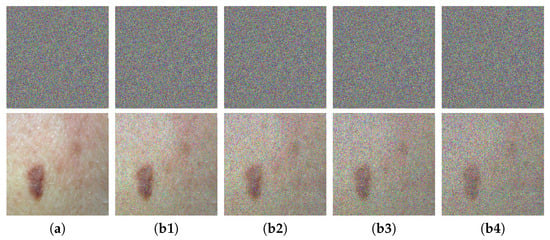

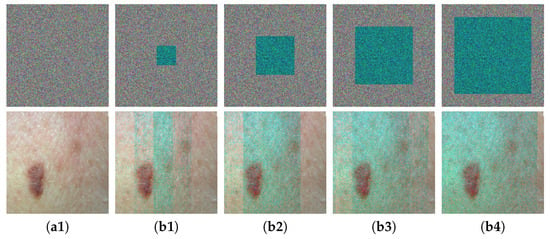

To simulate potential ciphertext corruption situations, we purposefully injected noise and deleted a portion of ciphertext pixels. Our experimental findings are illustrated in Figure 11 and Figure 12. As seen from Figure 11, when the ciphertext is subjected to noise interference, the decryption output quality of MIES-FHNN-DE is contingent upon the noise strength. With a low noise strength (such as 0.03), the decrypted image still maintains a satisfactory quality, offering adequate visual information to support clinical diagnosis.

Figure 11.

Robustness evaluation for MIES-FHNN-DE under noise interference: (a) original ciphertext of skin scar and its decrypted image; (b1) corrupted ciphertext (subjected to salt-and-pepper noise with an intensity of 0.01) and its decrypted image; (b2) corrupted ciphertext (noise intensity of 0.02) and its decrypted image; (b3) corrupted ciphertext (noise intensity of 0.03) and its decrypted image; (b4) corrupted ciphertext (noise intensity of 0.04) and its decrypted image.

Figure 12.

Robustness evaluation for MIES-FHNN-DE under pixel loss: (a1) original ciphertext of skin scar and its decrypted image; (b1) corrupted ciphertext ( pixel loss in the red channel) and its decrypted image; (b2) corrupted ciphertext ( pixel loss) and its decrypted image; (b3) corrupted ciphertext ( pixel loss) and its decrypted image; (b4) corrupted ciphertext ( pixel loss) and its decrypted image.

Analogously (see Figure 12), when the ciphertext image suffers from pixel loss, the quality of the decrypted output diminishes incrementally as the count of missing pixels grows. Notably, even when the red channel experiences a pixel loss of up to , MIES-FHNN-DE can still restore the majority of visual information. Conclusively, MIES-FHNN-DE possesses exceptional robustness. Even if the ciphertext experiences a certain amount of corruption, the quality of its decrypted output is sufficient to meet the demands of medical applications.

4.9. Efficiency Evaluation

Regarding the encryption protection of medical images, robust ciphertext security serves as a fundamental prerequisite for safeguarding patient privacy. Notably, high encryption efficiency, or encryption throughput, is also crucial for ensuring the practical applicability of proposed encryption protection. Otherwise, even encryption schemes with high security may still prove impractical in time-sensitive scenarios like telemedicine [23].

In addition to introducing the fractional-order HNN to enhance security, we have also incorporated several innovative design elements into our MIES-FHNN-DE method to improve encryption efficiency. These design elements encompass an improved keystream generation method, a differentiated encryption strategy, and dynamically partitioned vector-level encryption steps. We conducted a systematic evaluation of MIES-FHNN-DE’s encryption efficiency across varying input scales, with a comparison against the five latest IE schemes (see Table 4). As observed, under identical experimental conditions, MIES-FHNN-DE exhibits markedly reduced encryption times for images of varying sizes. This consistent performance advantage positions MIES-FHNN-DE as a computationally efficient IE scheme with significant practical advantages over existing alternatives.

Table 4.

Average encryption times (in seconds) for MIES-FHNN-DE versus five latest IE schemes.

4.10. Overall Comparison with Eight Latest Schemes

To further underscore the comprehensive superiority of MIES-FHNN-DE, we conducted an overall comparison between MIES-FHNN-DE and eight IE schemes reported in high-impact journals from IEEE, Elsevier, and MDPI [22,23,24,35,47,48,49,50]. The critical performance indicators of MIES-FHNN-DE and these compared IE schemes are summarized in Table 5. From a security perspective, MIES-FHNN-DE possesses a larger key space (), enabling superior resistance to brute-force attacks. Additionally, its average NPCR/UACI results are nearer to the optimal values ( and ), underscoring its stronger capability to thwart differential attacks. Finally, MIES-FHNN-DE attains the information entropy closest to the theoretical upper limit (8.0000 bits), reflecting the most uniform and random distribution of ciphertext pixels. Significantly, beyond its security merits, MIES-FHNN-DE also exhibits a strikingly prominent efficiency advantage, with an average encryption throughput of 102.5623 Mbps. Therefore, when benchmarked against these alternatives, MIES-FHNN-DE offers both superior protective efficacy and considerable efficiency benefits, rendering it more adaptable to the demands of diverse medical applications.

Table 5.

Overall comparison between MIES-FHNN-DE and the eight latest IE schemes.

5. Conclusions

Regarding the privacy protection of medical images, existing IE schemes still fall short in terms of security, particularly efficiency. Consequently, this paper innovatively integrates a novel 4D fractional-order HNN with a differentiated encryption strategy to meticulously construct a high-performance medical IE scheme named MIES-FHNN-DE.

Our MIES-FHNN-DE approach incorporates several innovative designs aimed at strengthening security and driving efficiency gains. Firstly, the 4D fractional-order HNN with complex dynamic characteristics is employed to generate a relatively shorter chaotic sequence. This design not only enhances security but also addresses the efficiency issues that previously arose when utilizing complex chaotic systems. Secondly, all input pixels are segmented and weightedly fused into the H3B and L5B pixel matrices, which are then subjected to differentiated encryption. Thirdly, MIES-FHNN-DE employs the hash values of the fused pixel matrices to generate three dynamic control parameters, which are then utilized to enhance the dynamism and plaintext dependency of the encryption process. Fourthly, MIES-FHNN-DE generates the chaotic sequences solely using the secret key and further transforms them into the keystreams for encryption. This design resolves the key management challenges present in existing schemes. Finally, MIES-FHNN-DE leverages a plaintext-dependent dynamic partitioning mechanism and efficient vector-level operations in its diffusion, scrambling, and substitution steps. This further advances both the security and efficiency of the encryption process.

The purpose of this paper is to enhance the security and efficiency of medical image encryption to better meet the stringent privacy protection requirements in emerging medical fields. Based on our broad and thorough evaluation and comparative study on MIES-FHNN-DE, we can confidently state that we have achieved this purpose. The experimental findings and analysis indicate that MIES-FHNN-DE features a large key space (), excellent key sensitivity, near-zero pixel correlations (<0.002), high ciphertext entropy values (>7.999), extremely uniform ciphertext pixel distributions, superior resistance to differential attacks (with average NPCR and UACI values of and ), and strong robustness against data loss. Remarkably, MIES-FHNN-DE attains an average encryption rate as high as 102.5623 Mbps, far outperforming the latest IE schemes reported in some high-impact journals. In contrast to current schemes, our MIES-FHNN-DE method can more effectively cater to the requirements of diverse emerging medical applications, such as telemedicine, medical cloud storage, medical cloud computing, and intelligent medical analysis.

Although our work centers on medical image encryption, its designs and innovations are extendable. The 4D fractional-order HNN-based approach for highly random keystream generation and our optimized encryption strategies can apply to audio, video, and text encryption, among others. Efficiency-boosting techniques like differentiated encryption and dynamic partitioning also show promise in other data security areas. In future work, we aim to further optimize the generation of keystreams. Specifically, we will focus on constructing novel fractional-order chaotic systems with superior chaotic performance and designing more efficient keystream generation processes. Additionally, we will explore the application of high-performance fractional-order chaotic systems in the field of medical video encryption to overcome the performance bottlenecks of existing schemes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.F., J.Z., X.Z., and Z.Z.; methodology, W.F., J.Z., and X.Z.; software, W.F. and K.Z.; validation, Y.C., B.C., and H.W.; formal analysis, J.Z., Y.C., and B.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.F., K.Z., and C.Y.; writing—review and editing, K.Z., J.Z., X.Z., C.Y., and Z.Z.; project administration, W.F., K.Z., and C.Y.; funding acquisition, W.F., J.Z., H.W., and C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 2024AFB544), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2023A1515011717), the Projects of Sichuan Provincial Engineering Research Center for BIM+ Applications and Intelligent Visualization Technology (Grant No. BIM-2024-Z-01), the Sichuan Provincial Research Projects on Educational Information Technology (Grant No. kt202409232250010), the Special Projects for Key Fields of the Education Department of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2024ZDZX1048), and the Cultivation Category Research Projects of Panzhihua University (Grant No 035001717).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this paper:

| IE | Image encryption |

| HNN | Hopfield neural network |

| MIES-FHNN-DE | Medical IE scheme based on 4D fractional-order HNN and differentiated encryption |

| NPCR | Number of pixels change rate |

| UACI | Unified average changing intensity |

| ANN | Artificial neural networks |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| 2D-ELMM | Two-dimensional enhanced logistic modular map |

| H3B | High 3-bit |

| L5B | Low 5-bit |

| SAC | Strict avalanche criterion |

| CC | Correlation coefficient |

References

- Waseem; Ullah, A.; Awwad, F.A.; Ismail, E.A.A. Analysis of the corneal geometry of the human eye with an artificial neural network. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luo, D.; Deng, Q.; Yang, G. Dynamics analysis and FPGA implementation of discrete memristive cellular neural network with heterogeneous activation functions. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 187, 115471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y. The multiple frequency conversion sinusoidal chaotic neural network and its application. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Su, D.; He, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yin, H. Resonant tunneling diode cellular neural network with memristor coupling and its application in police forensic digital image protection. Chin. Phys. B 2025, 34, 050502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wang, C.; Yu, F.; Sun, J.; Du, S.; Deng, Z.; Deng, Q. A review of chaotic systems based on memristive Hopfield neural networks. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Nie, X.; Zheng, W.X.; Cao, J. Multistability of state-dependent switched fractional-order Hopfield neural networks with mexican-hat activation function and its application in associative memories. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, D. Balance optimization method of energy shipping based on Hopfield neural network. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 67, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tang, D.; Lin, H.; Yu, F.; Sun, Y. High-dimensional memristive neural network and its application in commercial data encryption communication. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 242, 122513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Chen, Y. Design and encryption application of multi-scroll chain-loop memristive neural networks with initial-boosting coexisting attractors. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 187, 115473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; He, S.; Yao, W.; Cai, S.; Xu, Q. Bursting firings in memristive Hopfield neural network with image encryption and hardware implementation. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Fu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. In-Memory Computing Circuit Implementation of Complex-Valued Hopfield Neural Network for Efficient Portrait Restoration. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2023, 42, 3338–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Kong, X.; Yao, W.; Zhang, J.; Cai, S.; Lin, H.; Jin, J. Dynamics analysis, synchronization and FPGA implementation of multiscroll Hopfield neural networks with non-polynomial memristor. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 179, 114440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, C.; Deng, Q. Symmetric multi-double-scroll attractors in Hopfield neural network under pulse controlled memristor. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 14463–14477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z. Memristive Hopfield neural network with multiple controllable nonlinear offset behaviors and its medical encryption application. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 183, 114944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Jin, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhu, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, X. Fractional-order heterogeneous neuron network based on coupled locally-active memristors and its application in image encryption and hiding. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 187, 115397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zhang, S.; Su, D.; Wu, Y.; Gracia, Y.M.; Yin, H. Dynamic analysis and implementation of FPGA for a new 4D fractional-order memristive Hopfield neural network. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhang, F.; Huang, T.; Lu, M. Medical image encryption based on Josephus scrambling and dynamic cross-diffusion for patient privacy security. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 9250–9263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Hu, G.; Erkan, U.; Toktas, A. High-efficiency medical image encryption method based on 2D Logistic-Gaussian hyperchaotic map. Appl. Math. Comput. 2023, 442, 127738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. A memristive fully connect neural network and application of medical image encryption based on central diffusion algorithm. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 3778–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.N.; Singh, O.P.; Singh, A.K.; Agrawal, A.K. EiMOL: A secure medical image encryption algorithm based on optimization and the Lorenz system. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2023, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Z.; Gao, C.; Dai, Y.; Meng, X. Dynamic rotation medical image encryption scheme based on improved Lorenz chaos. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 13571–13597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Ji, L. A bidirectional cross-scrambling medical image encryption scheme incorporates compressed sensing and its application in IoMT. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Sun, P.; Lv, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ge, H.; Sun, C. A secure medical image encryption algorithm for IoMT using a Quadratic-Sine chaotic map and pseudo-parallel confusion-diffusion mechanism. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 270, 126521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Hua, H. Secure medical image encryption scheme for Healthcare IoT using novel hyperchaotic map and DNA cubes. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 264, 125854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Tsafack, N.; Boulila, W.; Ahmad, J.; Barba-Franco, J. ASB-CS: Adaptive sparse basis compressive sensing model and its application to medical image encryption. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, C.; Ye, R. Cryptanalysis and improvement of medical image encryption using high-speed scrambling and pixel adaptive diffusion. Signal Process. 2020, 167, 107286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; He, Y.; Li, H.; Li, C. Cryptanalysis and improvement of the image encryption scheme based on 2D logistic-adjusted-sine map. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 12584–12597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ahmad, M. Cryptanalysis and improvement of the image encryption scheme based on Feistel network and dynamic DNA encoding. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 145459–145470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shen, X.; Liu, S. Cryptanalyzing an image encryption algorithm underpinned by 2-D Lag-complex Logistic map. IEEE Multimed. 2024, 31, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Yang, H.; Li, C.; Shen, X. Cryptanalyzing an image encryption scheme using synchronization of memristor chaotic systems. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2024, 34, 2450138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.; Chen, P.; Li, C. Cryptanalyzing an image encryption algorithm underpinned by a 3-D boolean convolution neural network. IEEE MultiMedia 2024, 31, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Mou, J.; Li, B.; Banerjee, S.; Yan, H. Study on the Complex Dynamical Behavior of the Fractional-Order Hopfield Neural Network System and Its Implementation. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Lu, D.; Li, C. A novel memristive synapse-coupled ring neural network with countless attractors and its application. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 184, 115056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Tang, Q.; Yi, C.; Yang, Y. Constructing memristive Hindmarsh-Rose neuron with countless coexisting firings. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2024, 34, 2450113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, S.; Feng, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qin, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wozniak, M. Exploiting dynamic vector-level operations and a 2D-enhanced logistic modular map for efficient chaotic image encryption. Entropy 2023, 25, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, J. A cluster of 1D quadratic chaotic map and its applications in image encryption. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 204, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, L. Chaos-based image encryption: Review, application, and challenges. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Albor, E.; Romero-Arellano, A.; Brieva, J.; Gomez-Coronel, S.L. Color image encryption algorithm based on a chaotic model using the modular discrete derivative and Langton’s Ant. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Tang, C.; Wei, W. A novel adaptive image privacy protection method based on Latin square. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 10485–10508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Moroz, I.; Yang, Y. A joint image encryption based on a memristive Rulkov neuron with controllable multistability and compressive sensing. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 182, 114800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, O.; Erkan, U.; Toktas, A.; Gao, S. PSO-based image encryption scheme using modular integrated logistic exponential map. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toktas, F.; Erkan, U.; Yetgin, Z. Cross-channel color image encryption through 2D hyperchaotic hybrid map of optimization test functions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, U.; Toktas, A.; Memiş, S.; Lai, Q.; Hu, G. An image encryption method based on multi-space confusion using hyperchaotic 2D Vincent map derived from optimization benchmark function. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 111, 20377–20405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Qian, K.; Wen, H. Exploiting Newly Designed Fractional-Order 3D Lorenz Chaotic System and 2D Discrete Polynomial Hyper-Chaotic Map for High-Performance Multi-Image Encryption. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam, H.; Veeramalai, T.; Menon, A.R.; S., S.; Amirtharajan, R. Dual-domain image encryption in unsecure medium—A secure communication perspective. Mathematics 2023, 11, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zefreh, E.Z. An image encryption scheme based on a hybrid model of DNA computing, chaotic systems and hash functions. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 24993–25022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, T.; Feng, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Gan, L.; Li, C. A novel image encryption scheme based on non-adjacent parallelable permutation and dynamic DNA-level two-way diffusion. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 61, 102844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Yi, S.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, H. Cross-plane colour image encryption using a two-dimensional logistic tent modular map. Inf. Sci. 2021, 546, 1063–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, J.; He, Y. Image encryption algorithm based on plane-level image filtering and discrete logarithmic transform. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, X. Enhancing secure storage and sharing of multi-image in cloud environments using a novel chaotic map. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 264, 125897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).