A Novel Event-Dependent Intermittent Control for Synchronization of Fractional-Order Coupled Neural Networks with Mixed Delays and Higher-Order Interactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

2. Preliminaries and Model Description

2.1. Preliminaries

2.2. Model Description

3. Main Result

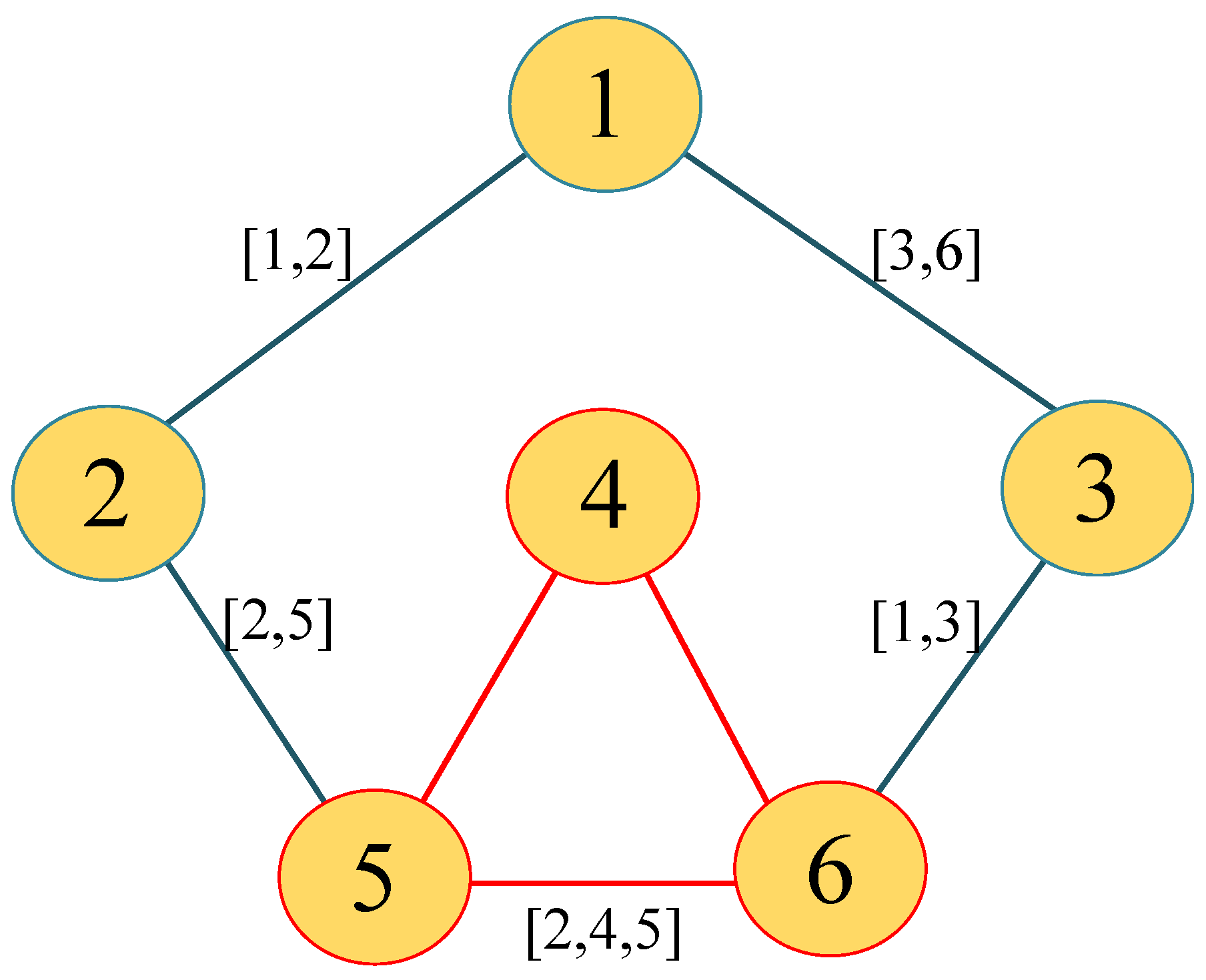

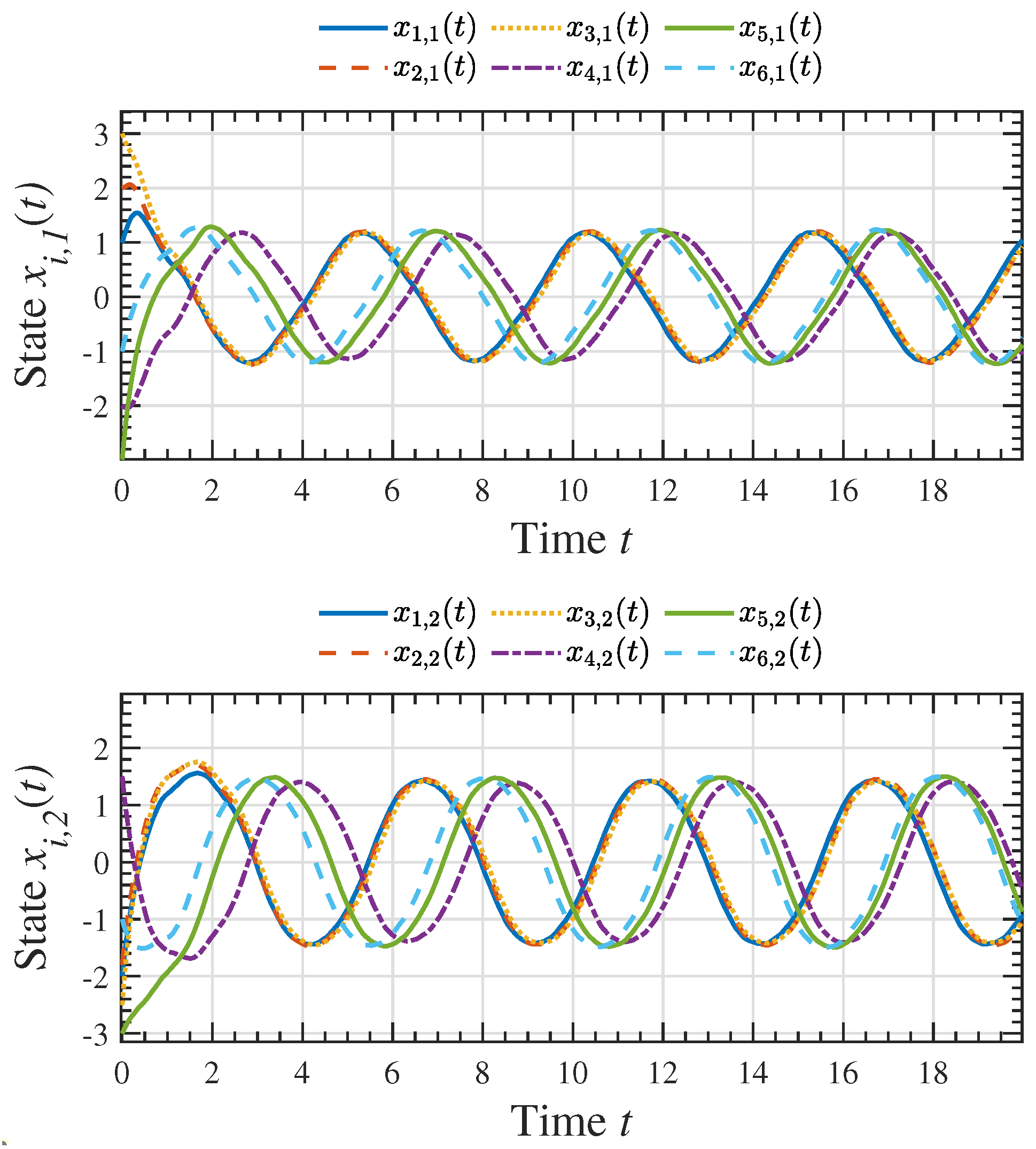

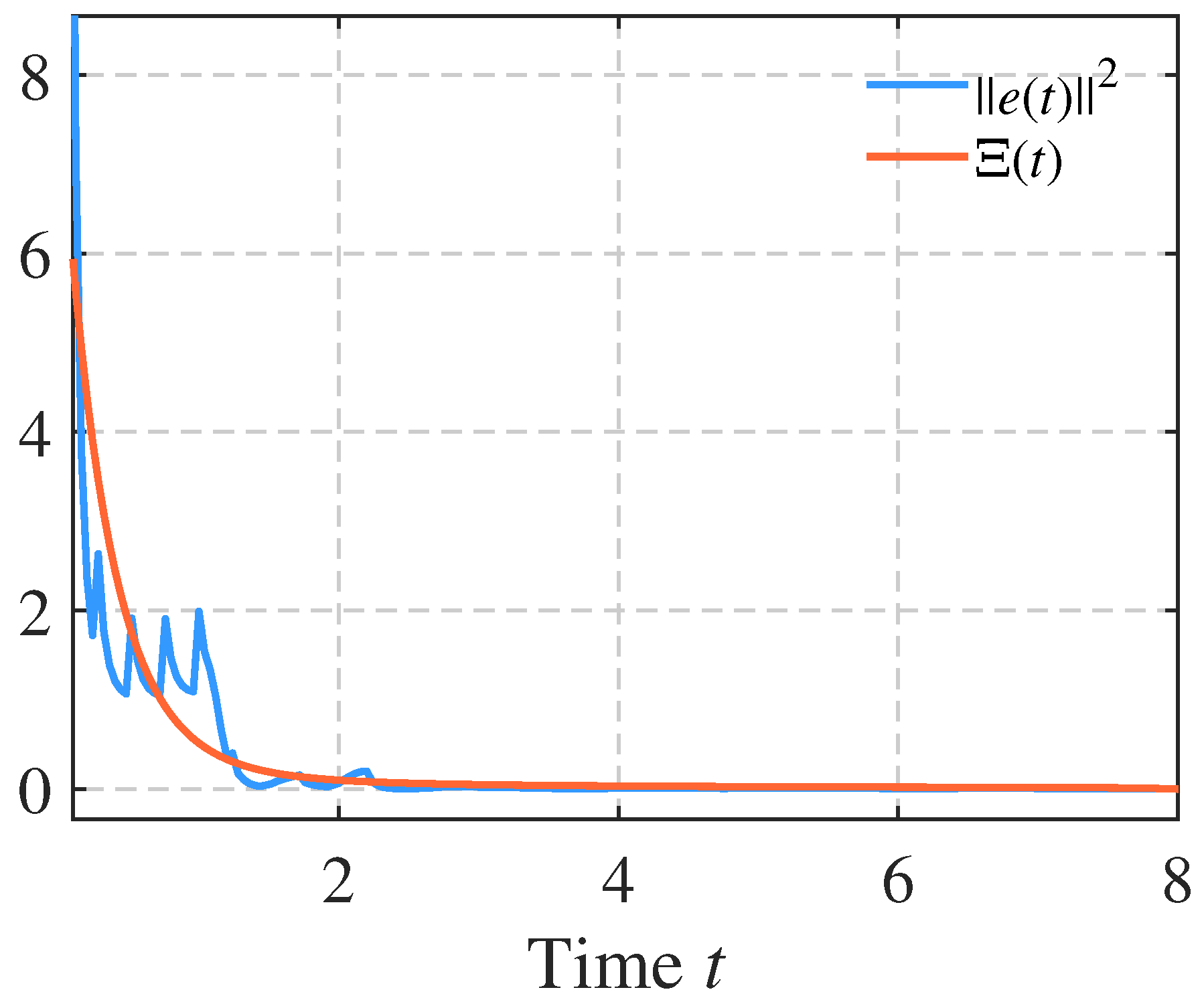

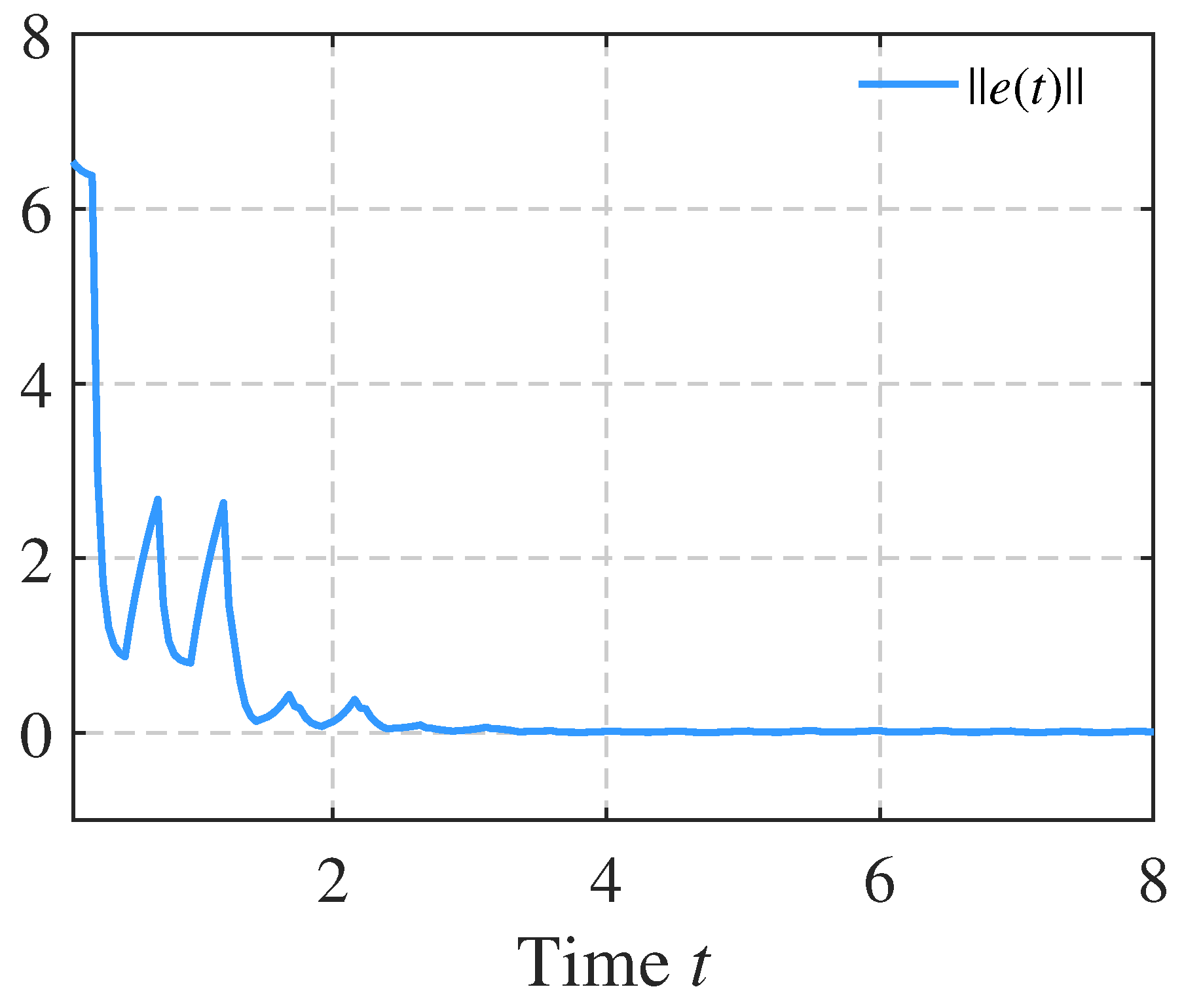

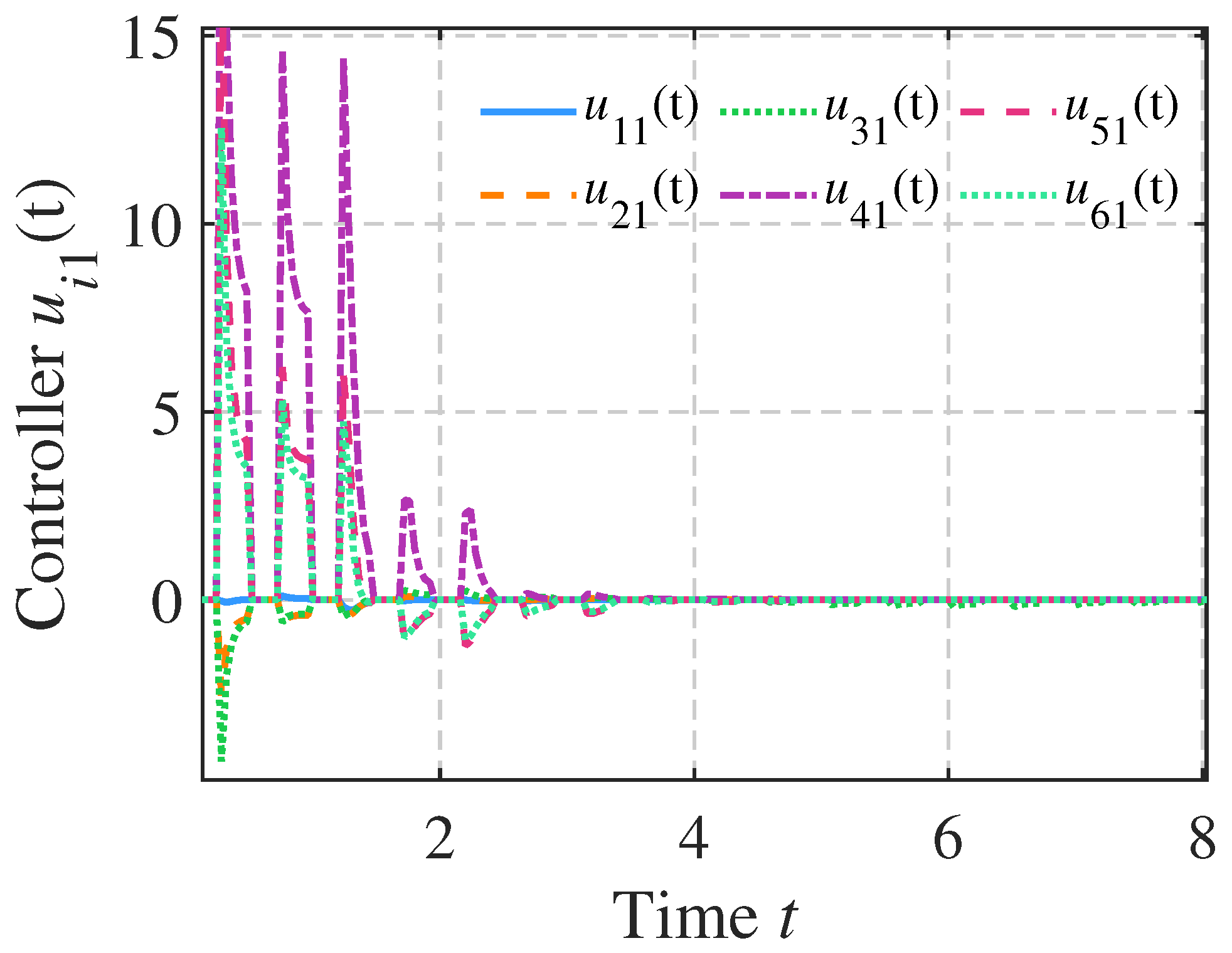

4. Numerical Examples

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, Y.; Wang, Z. Finite-time extended dissipative filtering for singular T-S fuzzy systems with nonhomogeneous Markov jumps. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 4574–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, N.; Wang, R. Odor pattern recognition of olfactory neural network based on neural energy. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 22421–22438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Su, X.; Shen, C.; Ma, X. Exponentially extended dissipativity-based filtering of switched neural networks. Automatica 2024, 161, 111465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria-Cerezo, A.; Olm, J.M.; di Bernardo, M.; Nuño, E. Modelling and control for bounded synchronization in multi-terminal VSC-HVDC transmission networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Pap. 2016, 63, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, M.; Cornejo, A.; Nagpal, R. Programmable self-assembly in a thousand-robot swarm. Science 2014, 345, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Ma, T. Variable impulsive bipartite coordination control of nonlinear systems with DoS attacks. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 8623–8640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zeng, D.; Baleanu, D. Fractional impulsive differential equations: Exact solutions, integral equations and short memory case. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2019, 22, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Deng, Z.; Baleanu, D.; Zeng, D. New variable-order fractional chaotic systems for fast image encryption. Chaos 2019, 29, 083103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleanu, D.; Wu, G. Some further results of the Laplace transform for variable-order fractional difference equations. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2019, 22, 1641–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhao, S.; Luo, X.; Yuan, Y. Synchronization for fractional-order extended Hindmarsh-Rose neuronal models with magneto-acoustical stimulation input. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 141, 110635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Cao, J. Dynamics in fractional-order neural networks. Neurocomputing 2014, 142, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacu, I. Effects of high-order interactions on synchronization of a fractional-order neural system. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2024, 18, 1877–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Jiang, N.; Liu, X.; Fan, L. Impulsive synchronization and parameter optimization for disturbed inertial memristive neural networks with actuator saturation. Phys. A 2025, 674, 130755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boya, B.; Ramakrishnan, B.; Effa, J.; Kengne, J.; Rajapopal, K. The effects of symmetry breaking on the dynamics of an inertial neural system with a non-monotonic activation function: Theoretical study, asymmetric multistability and experimental investigation. Phys. A 2022, 602, 127458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximo, J.O.; Armstrong, W.P.; Kraguljac, N.V.; Lahti, A.C. Higher-order intrinsic brain network trajectories after antipsychotic treatment in medication-naive patients with first-episode psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 96, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. Inverse optimal pinning synchronization control for higher-order networks on multi-directed hypergraphs. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 199, 116593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhang, X. Impact of higher-order interactions on amplitude death of coupled oscillators. Phys. A 2023, 622, 128803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Verma, U.K.; Mishra, A.; Yadav, K.; Sharma, A.; Varshney, V. Higher-order interaction in multiplex neuronal networks with electric and synaptic coupling. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 182, 114864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabbeik, M.; Jafari, S.; Perc, M. Synchronization in simplicial complexes of memristive Rulkov neurons. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1248976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrera-Megchun, A.; Padilla-Longoria, P.; Santos, G.J.; Espinal-Enriquez, J.; Bernal-Jaquez, R. Explosive synchronization driven by repulsive higher-order interactions in coupled neurons. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 196, 114864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Xie, X.; Li, W.; Wu, Y. Fuzzy-based bipartite quasi-synchronization of fractional-order heterogeneous reaction-diffusion neural networks via intermittent control. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Reg. Pap. 2024, 71, 3880–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Xue, L.; Ahn, C.K.; Liu, J. Stabilization of complex networks under asynchronously intermittent event-triggered control. Automatica 2024, 161, 111493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.M.; Wang, J.L. Intermittent control to stabilization of stochastic highly nonlinear coupled systems with multiple time delays. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 4674–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, H.; Zhao, J. Exponential synchronization and L2-gain analysis of delayed chaotic neural networks via intermittent control with actuator saturation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 3722–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Wang, Z.; Rong, N. Intermittent control for quasi-synchronization of delayed discrete-time neural networks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 51, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Y. Aperiodically intermittent dynamic event-triggered control for predefined-time synchronization of stochastic complex networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 970–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, L.; Zong, X. Fixed-time event-dependent intermittent control for reaction-diffusion systems. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2024, 34, 10331–10345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Wang, Z. Synchronization of coupled neural networks via an event-dependent intermittent pinning control. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 1928–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J. Finite-time inter-layer synchronization of duplex networks via event-dependent intermittent control. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 4889–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, K.; Ahn, C. Intermittent boundary control for synchronization of fractional delay neural networks with diffusion terms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 2900–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H.; Cao, J. Complete synchronization of discrete-time fractional-order T-S fuzzy complex-valued neural networks with time delays and uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 33, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, Y. Discrete fractional-order Halanay inequality with mixed time delays and applications in discrete fractional-order neural network systems. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2025, 28, 1384–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Wang, X.; Hui, M.; Zeng, Z. Quasi-synchronization of fractional multiweighted coupled neural networks via aperiodic intermittent control. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 54, 1671–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, J. Multiple Mittag-Leffler stability of fractional-order recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2017, 47, 2279–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, D.G. Transform Methods for Solving Partial Differential Equations; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S.; Ghaoui, L.; Feron, E. Linear Matrix Inequalities in System and Control Theory; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Z. Fractional-order vectorial Halanay-type inequalities with applications for stability and synchronization analyses. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 53, 1573–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, B.; Lu, J.; Shi, D. Selection of simplexes in pinning control of higher-order networks. Sci. Sin. Inf. 2024, 54, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambuzza, L.; Patti, F.; Gallo, L.; Lepri, S.; Romance, M.; Criado, R.; Frasca, M.; Latora, V.; Boccaletti, S. Stability of synchronization in simplicial complexes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhong, J.; Lu, J. Intermittent control for finite-time synchronization of fractional-order complex networks. Neural Netw. 2021, 144, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, S.; Li, W. Exponential stability of fractional-order complex multi-link networks with aperiodically intermittent control. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 4063–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Z.; Yang, D.; Li, H.; Yu, Y.; Liu, X.; Cattani, P. A Novel Event-Dependent Intermittent Control for Synchronization of Fractional-Order Coupled Neural Networks with Mixed Delays and Higher-Order Interactions. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120824

Wu Z, Yang D, Li H, Yu Y, Liu X, Cattani P. A Novel Event-Dependent Intermittent Control for Synchronization of Fractional-Order Coupled Neural Networks with Mixed Delays and Higher-Order Interactions. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):824. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120824

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Zhilin, Dongsheng Yang, Hong Li, Yongguang Yu, Xiang Liu, and Piercarlo Cattani. 2025. "A Novel Event-Dependent Intermittent Control for Synchronization of Fractional-Order Coupled Neural Networks with Mixed Delays and Higher-Order Interactions" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120824

APA StyleWu, Z., Yang, D., Li, H., Yu, Y., Liu, X., & Cattani, P. (2025). A Novel Event-Dependent Intermittent Control for Synchronization of Fractional-Order Coupled Neural Networks with Mixed Delays and Higher-Order Interactions. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120824