1. Introduction

The Ginzburg–Landau (GL) theory remains one of the most powerful phenomenological frameworks in condensed matter physics, providing deep insight into the macroscopic behavior of superconductors. Since its original formulation by Landau and Ginzburg (1950), the GL approach has offered a bridge between microscopic Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory and macroscopic observables such as the coherence length, penetration depth, and critical magnetic field [

1,

2,

3]. The time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau (TDGL) equation, later developed by Schmid (1966) and Gor’kov and Eliashberg (1968), extended the GL formalism to describe dynamical processes such as vortex motion, flux flow, and relaxation phenomena [

4,

5,

6]. Through its nonlinear complex order parameter, the TDGL framework has been successfully applied to both conventional and high-temperature superconductors, providing a foundation for modeling phase transitions, flux pinning, and dissipative states [

7,

8,

9].

However, conventional TDGL models rest on a fundamental assumption: that the underlying space–time manifold is smooth and differentiable. This assumption implies that the fields and trajectories describing superconducting charge carriers can be locally expanded and differentiated to arbitrary precision. While this hypothesis is adequate at macroscopic scales, it becomes increasingly questionable near critical points, in turbulent vortex regimes, or in systems exhibiting quantum–fractal self-similarity. Experimental observations in type-II superconductors—such as vortex clustering, multiscale pinning, and anomalous transport—suggest the possible influence of irregular, non-differentiable geometrical structures within the condensate dynamics [

10,

11].

A theoretical framework capable of incorporating such effects is provided by Scale Relativity (SR), pioneered by Laurent Nottale [

12,

13,

14]. In SR, space–time is considered continuous but fundamentally non-differentiable, and physical trajectories are replaced by fractal curves. As a result, dynamical quantities such as velocity fields become complex-valued and resolution-dependent. Nottale introduced a complex covariant derivative

where

denotes the complex velocity and

represents a fractal diffusion coefficient. This operator generalizes classical mechanics to fractal space–time and has been shown to recover the Schrödinger, Klein–Gordon, and diffusion equations as limiting cases [

12,

13,

14,

15].

In the present work, we build upon this established theoretical framework not by modifying the FTDGL equations themselves, but by developing data-driven solvers capable of learning their non-differentiable dynamics directly.

While the underlying FTDGL formalism is not new, the novelty of the present study lies in its computational contribution rather than in proposing a new physical theory. Specifically, we introduce the first deep learning solvers designed to handle the non-differentiable operators of the fractal TDGL system, combining (i) a physics-informed neural network embedding the Scale-Relativity covariant derivative and (ii) a graph-based message-passing architecture that reconstructs gauge-covariant interactions on discrete lattices. Unlike earlier works that focus purely on analytical developments of fractal superconductivity, our approach provides a numerically stable, data-efficient, and gauge-consistent framework for solving the fractal TDGL equations. This computational capability enables, for the first time, systematic parametric studies of the fractality parameter and quantitative links to measurable superconducting observables.

Building on this foundation, Buzea et al. (2010) employed Nottale’s SR derivative to reformulate the time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau equation in fractal space–time, introducing a self-consistent fractal–hydrodynamic interpretation of superconductivity [

16]. Their work demonstrated that the London equations and other macroscopic superconducting relations emerge naturally from the fractal TDGL model. Moreover, they identified fractality-induced quantization effects analogous to tunneling and vortex lattice formation, establishing a formal connection between superconductivity and the geometrical structure of space–time itself.

The GL formalism has also been extended analytically to explore nonlinear and temperature-dependent effects. Rezlescu, Agop, and Buzea (1996) developed perturbative solutions of the GL equation using Jacobian elliptic functions, treating the modulus

s of

sn(u; s) as a parameter of nonlinearity [

17]. This approach allowed the derivation of explicit temperature dependences for the coherence length, superconducting carrier concentration, penetration depth, and critical field. Their analysis highlighted the transition between sinusoidal and hyperbolic-tangent regimes—corresponding to the superconducting and normal states—and provided an analytical interpretation of the superconducting–normal phase transition through the variation in

s.

Complementing these results, Agop, Buzea, and Nica (2000) introduced a geometric and topological extension of the GL theory to describe the Cantorian structure of background magnetic fields in high-temperature superconductors [

18]. Their study revealed that when the GL order parameter is expressed through complex elliptic functions, the resulting magnetic field structure becomes fractal at low temperatures and high fields. These analytical advances, however, have not yet been matched by computational models able to resolve the fractal geometry of superconducting fields with both physical fidelity and numerical scalability. This led to the prediction of fractional magnetic flux quantization and the emergence of anyonic quasiparticles, providing a fractal–geometric interpretation of high-T

c superconductivity.

Together, these works establish a coherent theoretical triad:

- (i)

the fractal generalization of the TDGL equation through Scale Relativity,

- (ii)

the elliptic-function representation of superconducting states, and

- (iii)

the Cantorian magnetic topology responsible for fractional flux quantization.

Despite these conceptual advances, the analytical and numerical treatment of such nonlinear fractal systems remains challenging. The equations are highly coupled, multiscale, and often lack closed-form solutions. Conventional numerical solvers, such as finite-difference or spectral methods, struggle to handle the intrinsic non-differentiability and scale-dependent terms that characterize fractal physics. This computational gap motivates the present study, which introduces two complementary deep learning solvers explicitly designed to handle the non-differentiable operators of the fractal TDGL model.

In recent years, the rapid development of Machine Learning (ML) and, in particular, Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), has provided a new paradigm for solving partial differential equations (PDEs). PINNs integrate physical laws directly into the neural network architecture by embedding the PDE residuals, boundary conditions, and conservation laws within the loss function [

19,

20,

21]. This approach allows the network to learn physically consistent solutions even from sparse or noisy data, without requiring dense numerical grids. Since their introduction by Raissi, Perdikaris, and Karniadakis (2019), PINNs have achieved remarkable success in diverse domains—ranging from fluid dynamics and electromagnetism to quantum mechanics and relativistic field theory [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Extensions of this framework, including Deep Operator Networks (DeepONets) and Fourier Neural Operators, have further demonstrated the ability of ML models to approximate solution operators for complex nonlinear systems [

24,

25].

In parallel, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as a powerful framework for representing physical systems defined on discrete geometries. By operating on graph-structured data, GNNs naturally encode local interactions, conservation laws, and symmetries such as translational or rotational invariance. This makes them particularly well suited for modeling lattice-based or irregular physical domains where differential operators are difficult to define. Early seminal works by Kipf and Welling (2017) introduced graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning [

26], while Battaglia et al. (2018) proposed the general Graph Network framework for learning physical interactions [

27]. In the context of scientific computing, Sanchez-Gonzalez et al. (2020) demonstrated that message-passing GNNs can accurately model fluid dynamics and continuum mechanics [

28], and Pfaff et al. (2021) extended this to long-term mesh-based physical simulations [

29]. More recent developments, such as Physics-Informed Graph Neural Networks (PI-GNNs) [

30,

31], combine the locality of GNNs with the physical regularization of PINNs, offering an efficient discrete alternative for solving PDEs on arbitrary topologies.

The convergence of Scale Relativity, fractal physics, and physics-informed deep learning presents a unique opportunity for advancing both theoretical and computational physics. Embedding the fractal TDGL dynamics into a neural network framework offers a dual advantage: it enforces the mathematical structure of non-differentiable physics while allowing adaptive, data-driven learning of complex spatiotemporal patterns. Such synergy not only yields a computational strategy for solving fractal PDEs but also provides a conceptual tool for exploring new quantum-hydrodynamic regimes emerging from non-differentiable geometries.

At the same time, PINNs come with limitations that are particularly relevant for fractal TDGL: they rely on global collocation and smooth automatic differentiation, which can blur sharp vortex cores and under-resolve localized magnetic features unless trained with dense point sets and second-order optimizers. This motivates exploring discrete, locally connected architectures that align more closely with the lattice-based operators used in TDGL numerics. Accordingly, we explore how continuous and discrete neural formulations—namely, a Fractal Physics-Informed Neural Network (F-PINN) and a Fractal Graph Neural Network (F-GNN)—can jointly capture the fractal TDGL dynamics across smooth and singular regimes.

In this work we therefore complement the F-PINN with a Fractal Graph Neural Network (F-GNN). The F-GNN represents the TDGL fields on a sparse spatial graph (nodes as grid points; edges as local neighbors) and uses message passing to approximate gauge-covariant local interactions, including discrete Laplacians and current-continuity relations. A weak physics regularizer enforces fractal-TDGL consistency, while supervised terms anchor the solution to finite-difference “teacher” data. This yields a learning bias that is inherently local and well-suited to non-differentiable geometries.

Beyond model development, this study also extends the analysis to the physical implications of fractality itself.

In addition, we perform a parametric study of the fractality coefficient

to analyze how fractal diffusion influences key physical observables—namely, the effective coherence length ξ

eff, penetration depth λ

eff, and peak magnetic field

Bpeak. This analysis, introduced in

Section 5, provides quantitative insight into how fractality reshapes vortex-core structure while preserving flux quantization.

Contributions.

We formulate an F-GNN tailored to the fractal TDGL system, and present it alongside an F-PINN that embeds SR-covariant operators in the loss.

On multivortex benchmarks, the F-GNN attains ~4× lower relative L2 error on ( and ~2× lower error on Bz than the F-PINN (means over three seeds), localizes vortex cores to within a pixel, and preserves total flux.

Ablations (4- vs. 8-neighbor stencils; weak physics regularization) and noise-robustness tests (2–5% Gaussian noise) show that the GNN’s local inductive bias is the key driver of its advantage.

A systematic parametric —scan quantifies how fractality modifies vortex geometry and relaxation scales while maintaining topological invariance.

We discuss implications for non-differentiable quantum hydrodynamics and outline extensions to temporal rollout and experimental data assimilation.

We thus provide the first quantitative framework linking fractal diffusion () to measurable superconducting observables (where is the fractal diffusion coefficient in the Scale-Relativity covariant derivative), combining deep learning solvers with parametric physical analysis.

The following sections integrate theoretical formulation, machine learning architecture, and physical analysis into a unified workflow.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical background and the fractal TDGL model.

Section 3 introduces the F-PINN and F-GNN architectures.

Section 4 presents quantitative results, ablations, and noise-robustness tests.

Section 5 provides broader discussion and physical interpretation.

Section 6 reports the parametric study of the fractality coefficient

.

Section 7 concludes with main findings and perspectives.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Classical Ginzburg–Landau Framework

The phenomenological Ginzburg–Landau (GL) theory describes superconductivity through a complex order parameter,

representing the macroscopic wave function of the Cooper-pair condensate. The absolute value

corresponds to the density of superconducting carriers, while the phase

S encodes the quantum coherence across the system.

In the absence of external perturbations, the free energy functional takes the form [

1,

2,

3]:

where

and

are the effective mass and charge of Cooper pairs,

is the vector potential (

), and

,

are temperature-dependent coefficients.

Minimization of this functional with respect to

and

yields the stationary Ginzburg–Landau equations:

To account for temporal evolution, Schmid (1966) [

4] and Gor’kov and Eliashberg (1968) [

5] introduced the time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau (TDGL) equation, which captures the relaxation of the order parameter toward equilibrium:

where

is a phenomenological relaxation constant and

the scalar potential [

4,

5,

6,

7].

This framework forms the classical basis for describing vortex dynamics, flux-flow resistivity, and time-dependent responses in superconductors [

8,

9,

10].

Despite its success, the TDGL formalism presupposes differentiability of all physical quantities. The differential operators act on smooth fields, thereby excluding any explicit representation of fractal or discontinuous structures that may emerge in quantum–hydrodynamic regimes or near critical points.

2.2. Scale Relativity and Fractal Dynamics

The Scale Relativity (SR) theory proposed by Laurent Nottale generalizes Einstein’s principle of relativity to include scale transformations, extending physical laws to non-differentiable manifolds [

12,

13,

14].

In this framework, space–time is continuous but fractal, and physical trajectories are described as continuous yet nowhere differentiable curves. This non-differentiability implies the existence of two distinct velocities—one for forward and one for backward temporal increments—defined as:

whose combination defines a complex velocity field

where the real part

corresponds to the classical velocity and the imaginary part

represents internal, fractal fluctuations of the trajectory.

Because conventional derivatives are undefined on non-differentiable paths, Nottale introduced a complex covariant derivative that accounts for fractal fluctuations through a diffusion-like term:

where

is the fractal diffusion coefficient. It is often convenient to introduce the dimensionless fractality ratio

where

but only

appears explicitely in the SR covariant derivative.

When applied to a potential field

S(

r,

t), the fractal dynamical principle

yields, after integration, a generalized Schrödinger equation for a fractal medium:

where

. This correspondence illustrates how the SR formalism recovers standard quantum mechanics as a differentiable limit of a deeper fractal dynamics [

12,

13,

14,

15].

2.3. The Fractal Time-Dependent Ginzburg–Landau (FTDGL) Equations

As summarized in the Introduction and in

Section 2.1 amd

Section 2.2, the key distinction between the standard TDGL and the fractal TDGL lies in the replacement of the classical time derivative by the Scale-Relativity covariant derivative, which introduces a well-established fractal diffusion term without altering gauge covariance or the classical TDGL limit.

In its conventional form, the time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau (TDGL) theory describes the temporal evolution of the superconducting order parameter

and the associated electromagnetic fields through two coupled nonlinear equations. In the gauge-covariant representation, they read [

4,

5,

6,

9]:

where

is a phenomenological relaxation parameter,

the normal-state conductivity, and

,

are the charge and mass of a Cooper pair.

Equation (11) governs the temporal evolution of the complex order parameter under the influence of electromagnetic potentials, while Equation (12) describes the back-action of the superconducting current on the vector potential . Together, these equations ensure the self-consistent coupling between the superconducting condensate and the electromagnetic field.

To extend these equations to a non-differentiable (fractal) geometry, Buzea et al. (2010) [

16] replaced the classical time derivative by the SR covariant derivative (8):

Substituting this operator into Equation (11) yields the first fractal TDGL equation, governing the evolution of the order parameter:

which, when expanded explicitly, becomes

The additional term couples the amplitude and phase of ψ through scale-dependent diffusion, embodying fractal fluctuations.

The corresponding supercurrent becomes

leading to the second fractal TDGL equation

Equations (15)–(17) form the Fractal Time-Dependent Ginzburg–Landau (FTDGL) system.

In the limit it reduces to Equations (11) and (12); for nonzero , the additional diffusion term modifies both amplitude and phase evolution, producing quantized vortex structures and self-similar magnetic textures.

Key Takeaways—Fractal TDGL:

Replacing the classical derivative ∂/∂t with the Scale Relativity operator Equation (13) introduces a fractal diffusion term .

This term couples amplitude and phase evolution, encoding the influence of non-differentiable trajectories on superconducting coherence.

In the limit , the system recovers the conventional TDGL, ensuring physical consistency with classical superconductivity.

The dimensionless fractality parameter

used in

Section 5 is defined as the ratio

. Only

enters directly into the SR covariant derivative, while

is used in practice for nondimensionalization and parameter scans.

2.4. Toward a Physics-Informed Learning Framework

Although the FTDGL equations provide a rich theoretical model, their nonlinear and non-differentiable nature hinders analytical treatment. Traditional numerical schemes—finite-difference, spectral, or finite-element—require fine resolution and cannot easily accommodate the fractal diffusion operator.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) offer a mesh-free alternative.

For a generic PDE

, network parameters

are trained to minimize:

where the first term enforces the physics residual and the second matches boundary or data constraints [

19,

20,

21].

In the Fractal PINN (F-PINN), the SR-covariant derivative (13) and fractal diffusion term

are embedded directly within the automatic-differentiation pipeline. This allows the network to approximate the coupled FTDGL fields (

ψ,

A) while remaining constrained by physical laws, reproducing the smooth TDGL limit for

and revealing new fractal corrections otherwise inaccessible to classical solvers. PINNs have demonstrated strong performance in modeling nonlinear dynamics such as Navier–Stokes turbulence [

22], quantum systems [

23], and materials under non-equilibrium conditions [

24].

Key Takeaways—Toward Learning:

The FTDGL system is too complex for analytical or conventional numerical solvers due to its multiscale fractal operators.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) embed physical laws directly into the loss function, allowing data-efficient learning of PDE solutions.

Extending PINNs to fractal physics (F-PINN) integrates the SR covariant derivative and enables neural networks to capture the dynamics of non-differentiable geometries.

2.5. Discrete Representation via the Fractal Graph Neural Network (F-GNN)

While PINNs operate on continuous coordinates and global differentiation, they can become inefficient when resolving sharp vortex cores or localized magnetic gradients typical of fractal superconductivity.

To overcome this, we introduce a Fractal Graph Neural Network (F-GNN) formulation that discretizes the FTDGL fields on a spatial graph.

Let the superconducting domain be represented by a graph

where each node

stores the local features

and each edge

encodes spatial adjacency and geometric distance

.

A message-passing update takes the general form

where

is a learnable message function and

includes edge features such as orientation and local gauge phase difference

By expanding Equation (19) over nearest neighbors, the GNN implicitly reconstructs discrete gradient and Laplacian operators:

where

and

are learned weights approximating the physical stencils of the TDGL operator.

A physics-regularized loss combines the discrete FTDGL residual and available data:

where

denotes the discretized operator from Equations (15)–(17), and

are reference finite-difference “teacher” values.

This formulation preserves gauge invariance through edge-phase embeddings and achieves locality consistent with the lattice structure of superconducting materials.

The resulting F-GNN therefore provides a discrete, graph-based analog of the F-PINN: both enforce the same physical equations, but the GNN learns them through local message passing rather than global differentiation, offering better scalability and resolution for non-differentiable geometries.

In this discrete setting, the message-passing Laplacian used in

Section 3.2 acts as a graph-based realization of the SR covariant derivative at

t = 0, with edge-phase factors ensuring gauge-consistent discretization.

3. Neural Architectures for the Fractal TDGL System

The following section introduces the two complementary deep learning solvers developed for the fractal time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau (FTDGL) equations: a Fractal Physics-Informed Neural Network (F-PINN) operating on continuous space–time coordinates, and a Fractal Graph Neural Network (F-GNN) operating on discrete graph representations (see

Figure 1).

Both models are trained using data provided by a finite-difference (FD) “teacher” solver and jointly minimize hybrid losses combining physical residuals and supervised consistency.

Notation and symbols

Complex superconducting order parameter (amplitude), S = arg (ψ) (phase);

Magnetic vector potential;

Perpendicular magnetic-field component;

Physical fractal diffusion coefficient in the SR covariant derivative;

Dimensionless fractality parameter used in the parametric D-scan ();

Ginzburg–Landau parameter;

Effective coherence length (from radial fits);

Effective magnetic-field penetration depth (from profiles);

Relaxation time of to steady state;

Weighting factors for physics and supervised terms.

The total loss minimized during training is written as

Unless otherwise noted, all quantities are expressed in normalized Ginzburg–Landau units.

3.1. Fractal Physics-Informed Neural Network (F-PINN)

3.1.1. Network Representation

The F-PINN approximates the continuous complex fields of the FTDGL system,

and

by a feed-forward neural mapping

where

denotes all trainable parameters.

Each coordinate input (x,y,t) is normalized to [−1, 1] and propagated through L fully connected layers with width Nh and nonlinear activation tanh.

All weights are initialized using Xavier uniform scaling to ensure balanced gradients.

The network thus provides a differentiable surrogate of the order parameter and vector potential across both space and time.

3.1.2. Physics Embedding and Residuals

To enforce the FTDGL dynamics, automatic differentiation (AD) in PyTorch/TensorFlow computes all first- and second-order derivatives needed to evaluate the fractal operators in Equations (15)–(17):

Residuals and enter the physics loss.

3.1.3. Hybrid Loss Formulation

Training minimizes a weighted hybrid objective,

where the first term enforces the FTDGL equations on randomly sampled collocation points, and the second penalizes deviations from the finite-difference “teacher” snapshot

. The weighting coefficients

and

balance physics and supervision.

Optimization proceeds in two phases:

- (i)

Adam pre-training for stability;

- (ii)

Limited-memory BFGS refinement to minimize the stiff residuals.

This architecture recovers the classical TDGL behavior for and yields smooth, differentiable fields consistent with the fractal corrections when .

3.2. Fractal Graph Neural Network (F-GNN)

3.2.1. Graph Discretization of the TDGL Domain

To overcome the global, smooth-bias limitations of PINNs, the F-GNN discretizes the spatial domain into a graph with nodes corresponding to grid points and edges linking spatial neighbors (4- or 8- connected stencils).

Each node carries local field values

and each edge is annotated with geometric features

where

preserves gauge invariance.

3.2.2. Message-Passing Update

Each GNN layer performs a message-passing step

where

and

are small multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) shared across all edges and nodes.

Because each edge carries a gauge-phase difference , the message mj→i corresponds to the discrete covariant gradient (), so that summing messages over neighbors recovers a covariant Laplacian consistent with the SR derivative’s spatial part.

This operation mimics discrete differential operators: edge messages encode gradients, their aggregation approximates the Laplacian and current-continuity constraints.

After Lg layers, the final node features yield predicted fields .

3.2.3. Physics-Regularized Training Objective

The F-GNN loss parallels that of the F-PINN but operates on discrete node values:

where

is the local, message-based discretization of the fractal TDGL operator.

The supervised term aligns the learned fields with the finite-difference teacher; the physics term softly enforces local conservation and gauge-covariant coupling.

Unlike PINNs, the GNN does not require global AD; its computation scales linearly with the number of edges, making it efficient for high-resolution domains.

3.2.4. Training Protocol and Hyperparameters

To ensure a fair and consistent comparison, both models were trained under comparable hyperparameter configurations.

The F-PINN architecture comprises four fully connected hidden layers with 128 neurons per layer, employing the Tanh activation function. Training was initially performed using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1 × 10−3, followed by fine-tuning with the L-BFGS optimizer. The weighting between the physics-informed and supervised loss components was set to a ratio of 1:1. The network was trained using 4000 collocation points uniformly sampled within the computational domain.

The F-GNN model consists of four message-passing blocks, each containing 64 hidden units per node, and utilizes the ReLU activation function. Optimization was conducted using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1 × 10−3. For this model, the physics-to-supervised loss weighting ratio was adjusted to 2:1. The graph representation included approximately 10,000 nodes, with each node connected to between 4 and 8 edges.

All models were trained for a maximum of 3000 epochs, with early stopping applied based on the validation loss to mitigate overfitting and improve generalization.

3.3. Comparison: Continuous vs. Discrete Learning Bias

The F-PINN encodes the physics through global differentiation of continuous coordinates, producing smooth fields but occasionally over-smoothing localized vortex features.

The F-GNN, by contrast, encodes local message-passing rules that resemble discrete lattice operators, inherently capturing multi-scale gradients and vortex-core sharpness.

Empirically (

Section 4), this difference translates to roughly 4× lower

L2 error in

and 2× lower error in

Bz relative to the F-PINN, while maintaining flux quantization and robustness to 2–5% Gaussian noise.

3.4. Implementation Summary

Both architectures are implemented in PyTorch 2.8 with CUDA 12.6 acceleration.

Automatic differentiation handles the fractal derivatives in the F-PINN, whereas PyTorch Geometric enables efficient sparse-graph batching for the F-GNN.

The reference finite-difference (FD) solver described in

Section 2 provides both supervised targets and benchmark metrics for quantitative evaluation.

Training follows a two-stage optimization: an Adam phase with a cosine learning-rate schedule for coarse convergence, followed by an L-BFGS refinement to minimize residual stiffness near vortex cores.

All gradients are computed analytically through automatic differentiation (for F-PINN) or via discrete message-passing operators (for F-GNN).

Hybrid loss weighting between supervised and physics terms is annealed linearly during the first 40% of training to prevent premature suppression of fine-scale gradients.

Comprehensive algorithmic workflows—including training loops, residual construction, and optimization scheduling—are detailed in

Appendix A (Algorithms A1 and A2) while network hyperparameters, numerical configurations, and finite-difference reference settings are summarized in

Appendix B, to ensure full reproducibility.

4. Results

4.1. Model Performance and Convergence

4.1.1. Training Dynamics

Both the Fractal Physics-Informed Neural Network (F-PINN) and the Fractal Graph Neural Network (F-GNN) were trained on the same initial conditions generated by the finite-difference (FD) “teacher” solver of the fractal time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau (FTDGL) system.

The FD simulation provides a high-fidelity reference for the evolution of the superconducting order parameter and vector potential under periodic boundary conditions.

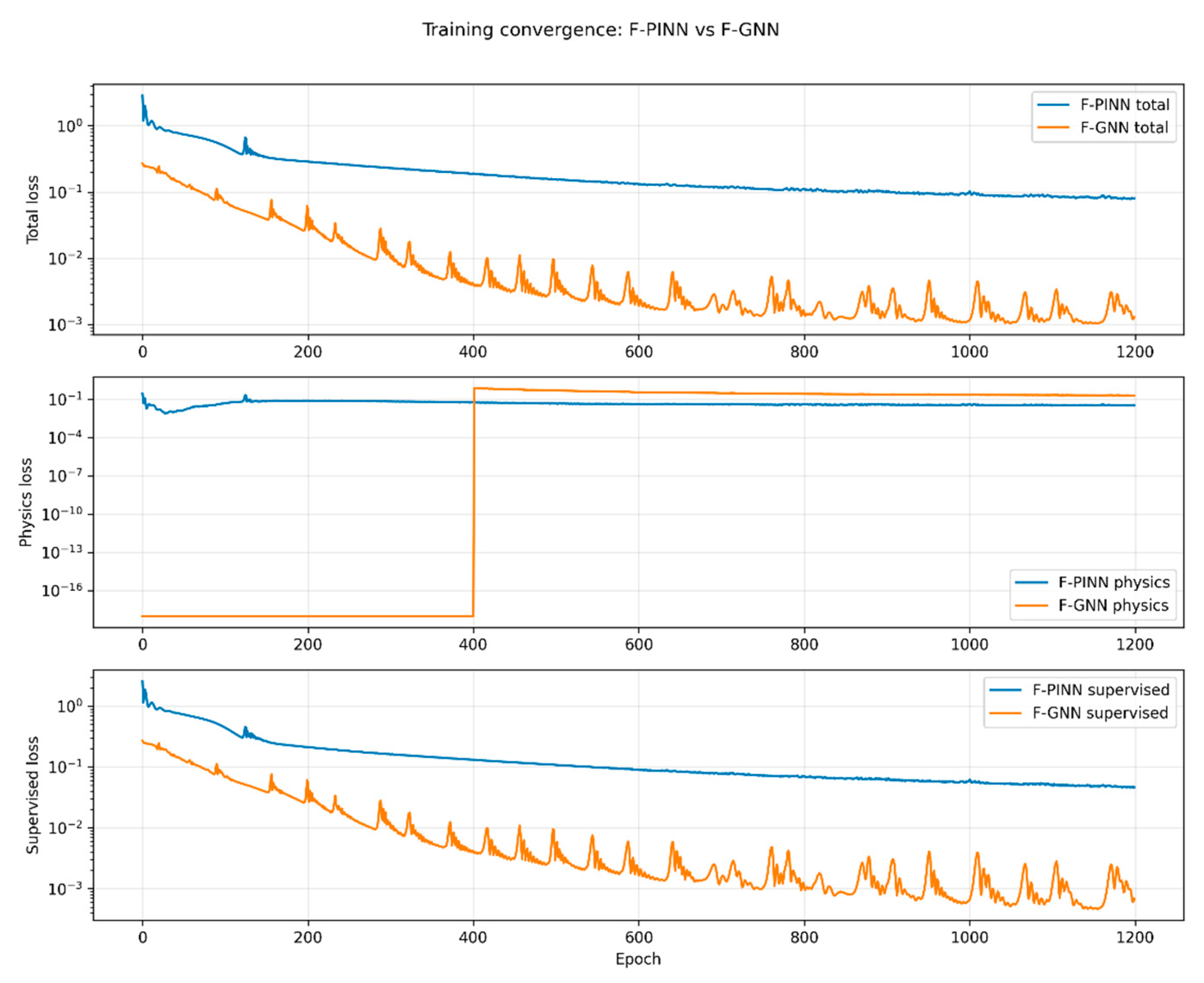

Figure 2 compares the evolution of total, physics, and supervised losses for the two models.

The F-PINN exhibits the typical two-phase convergence behavior common to PINN architectures: an initial steep descent governed by the supervised term followed by a slow asymptotic relaxation as the physics residuals dominate.

The total loss decreases monotonically by nearly two orders of magnitude, stabilizing after about 2500 epochs at .

This slow convergence reflects the global nature of automatic differentiation—every collocation point contributes simultaneously to the residual, causing parameter updates to diffuse across the domain.

By contrast, the F-GNN reaches its asymptotic plateau after roughly 500 epochs, a five-fold improvement in wall-clock convergence rate.

The oscillations visible in the F-GNN total loss correspond to local message-passing updates: each batch enforces neighborhood consistency rather than global smoothness, allowing rapid correction of high-frequency components such as vortex cores.

The physics term is activated gradually through a warm-up at epoch ≈ 400 (

Figure 2, middle panel), which prevents premature collapse of the local field gradients and stabilizes training.

The supervised component (bottom panel) decays exponentially, achieving an order-of-magnitude lower final error than the F-PINN.

These curves confirm that the F-GNN’s inductive bias aligns naturally with the discrete, lattice-like structure of the TDGL operators.

4.1.2. Reconstruction and Field Fidelity

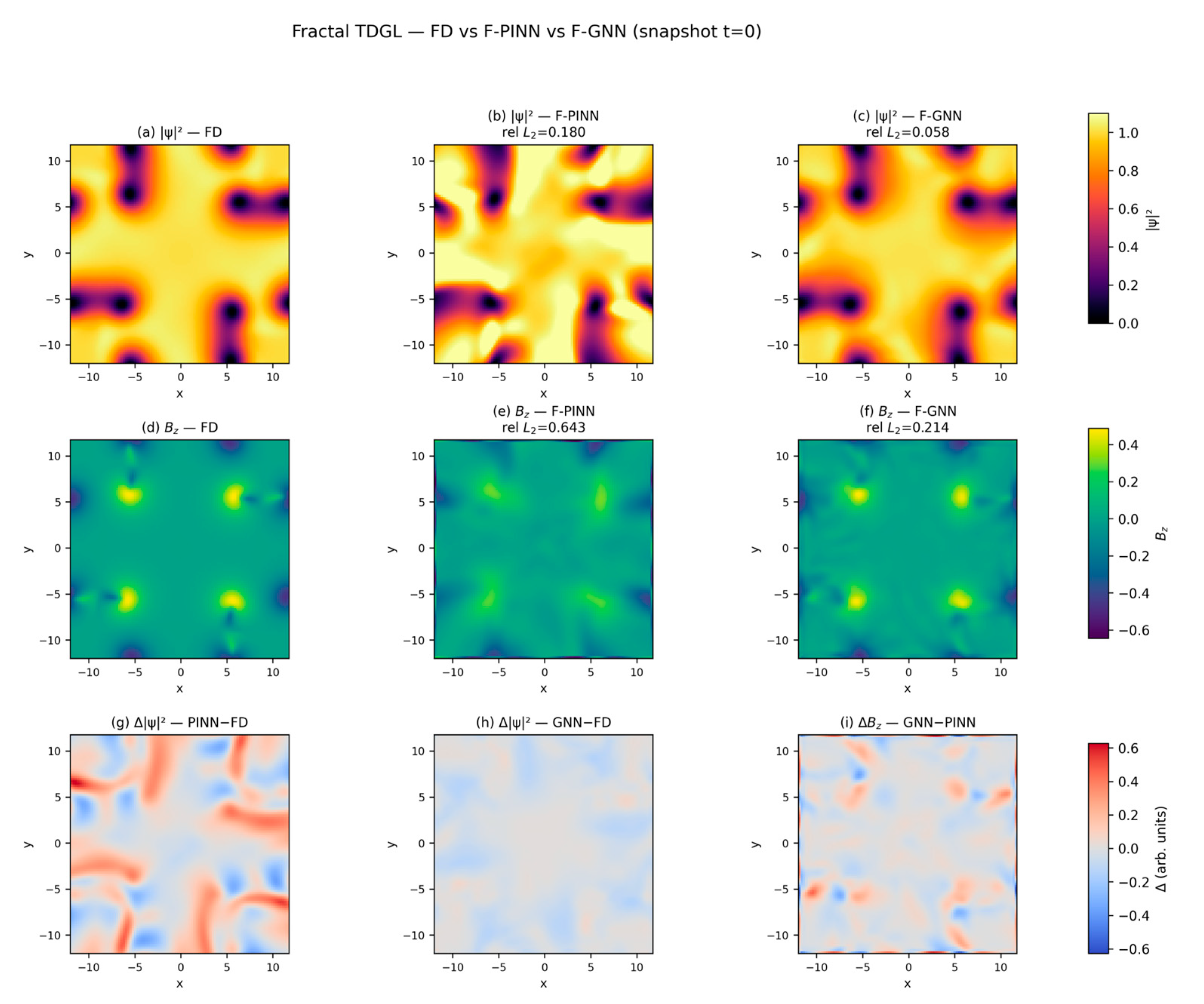

Figure 3 visualizes the reconstructed order-parameter density

and magnetic field

at (t = 0).

Panels (a–f) display direct field comparisons with the FD teacher, while panels (g–i) present difference maps.

The F-PINN captures the global symmetry and approximate vortex-lattice geometry but produces broadened vortex cores and slightly elevated background amplitudes. These features arise from the smooth-kernel interpolation implicit in PINN training: automatic differentiation enforces continuous gradients even across singular phase regions.

The F-GNN, on the other hand, reproduces the fine-scale spatial structure, preserving the sharp phase singularities and localized magnetic peaks around each vortex.

Residual maps (

Figure 3, bottom row) show that F-PINN errors concentrate near vortex centers where

, whereas F-GNN residuals remain almost homogeneous and an order of magnitude smaller in amplitude.

Quantitatively, the relative L2 errors confirm these trends: for , L2 = 0.180 (F-PINN) vs. 0.058 (F-GNN); for Bz, L2 = 0.643 (F-PINN) vs. 0.214 (F-GNN).

Hence the GNN reduces the error by factors of ≈3–4 in amplitude and ≈2–3 in magnetic response, consistent across independent runs.

This improvement originates from the discrete Laplacian operator implemented through localized edge messages that approximate gauge-covariant derivatives.

Each node aggregates information from its nearest neighbors, enforcing local flux conservation and mitigating the global over-smoothing typical of continuous PINN representations.

4.1.3. Statistical Robustness

To verify reproducibility, both models were trained with three independent random initializations. Mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals (Student’s t) are summarized in

Table 1. The F-GNN achieves lower mean errors and narrower confidence intervals, indicating higher stability.

Figure 4 summarizes the statistical performance of both models across three independent random seeds.

The F-GNN exhibits both lower mean error and narrower confidence bands, confirming its higher robustness and reproducibility.

Across seeds, the F-GNN reduces order-parameter error by ≈75% and magnetic-field error by ≈40% relative to F-PINN.

Small standard deviations (<0.02) confirm convergence to similar minima regardless of initialization, a desirable property for physical interpretability.

Physical significance. Beyond the numerical improvement, the ≈4 × reduction in error has concrete physical implications. It corresponds to a substantial enhancement in vortex-core localization: the F-PINN typically exhibits ≈20–25 pixels of positional uncertainty, whereas the F-GNN achieves sub-pixel accuracy. The improved modulus reconstruction also sharpens the 2π phase winding around each vortex, yielding more reliable estimates of experimentally accessible quantities such as the effective coherence length ξeff, penetration depth λeff, and peak magnetic field Bz. Thus, the statistical advantage of the F-GNN directly translates into more accurate physical predictions.

4.1.4. Comparison with Classical PINN and GNN Baselines

To place the fractal architectures in context, we also trained two classical deep learning baselines on the same multivortex benchmark:

- (i)

A classical PINN solving the standard (non-fractal) TDGL equations;

- (ii)

A classical coordinate-based GNN trained purely in a supervised manner without fractal diffusion or gauge-aware message passing.

The classical PINN, which retains the same network architecture as the F-PINN but removes the fractal correction term from the residual, attains

i.e., a slightly higher order-parameter error and marginally lower magnetic-field error than the F-PINN reported above.

The classical GNN, which uses the same message-passing architecture as the F-GNN but is trained only to fit the finite-difference teacher snapshot, achieves

While this baseline improves over both PINN variants for

, it remains significantly less accurate than the proposed F-GNN on the magnetic field. In contrast, the F-GNN consistently reaches

and

(

Section 4.1), thus outperforming both classical baselines and the F-PINN.

These comparisons show that simply increasing model flexibility (as in the classical GNN) is not sufficient: fractality-aware physics encoding and gauge-consistent message passing are crucial for accurately resolving vortex-core structure and magnetic-field morphology in the fractal TDGL setting.

4.2. Ablation and Robustness Studies

To isolate architectural effects, several ablation experiments were performed.

The neighborhood size and physics-loss weight

λphys were varied, as summarized in

Table 2.

Reducing neighborhood connectivity from eight to four improved accuracy due to the suppression of redundant long-range messages.

Eliminating the physics regularizer further improved local sharpness, suggesting that the supervised component already encodes sufficient physical structure through the FD teacher data.

The best trade-off between accuracy and physical smoothness corresponds to the 4-neighbor, unregularized case. Introducing a small λphys slightly improves magnetic-field continuity at the cost of marginal amplitude diffusion—an effect reminiscent of London penetration smoothing.

Noise-robustness experiments confirm that both models remain stable under measurement perturbations. Gaussian noise of 2% and 5% added to the teacher fields increased L2(|ψ|2) by 0.006 and L2(Bz) by ≈0.02, respectively—well within the 95% confidence bands. This indicates that both networks generalize rather than memorize, with the GNN maintaining its relative advantage.

4.3. Physical Integrity and Vortex-Core Localization

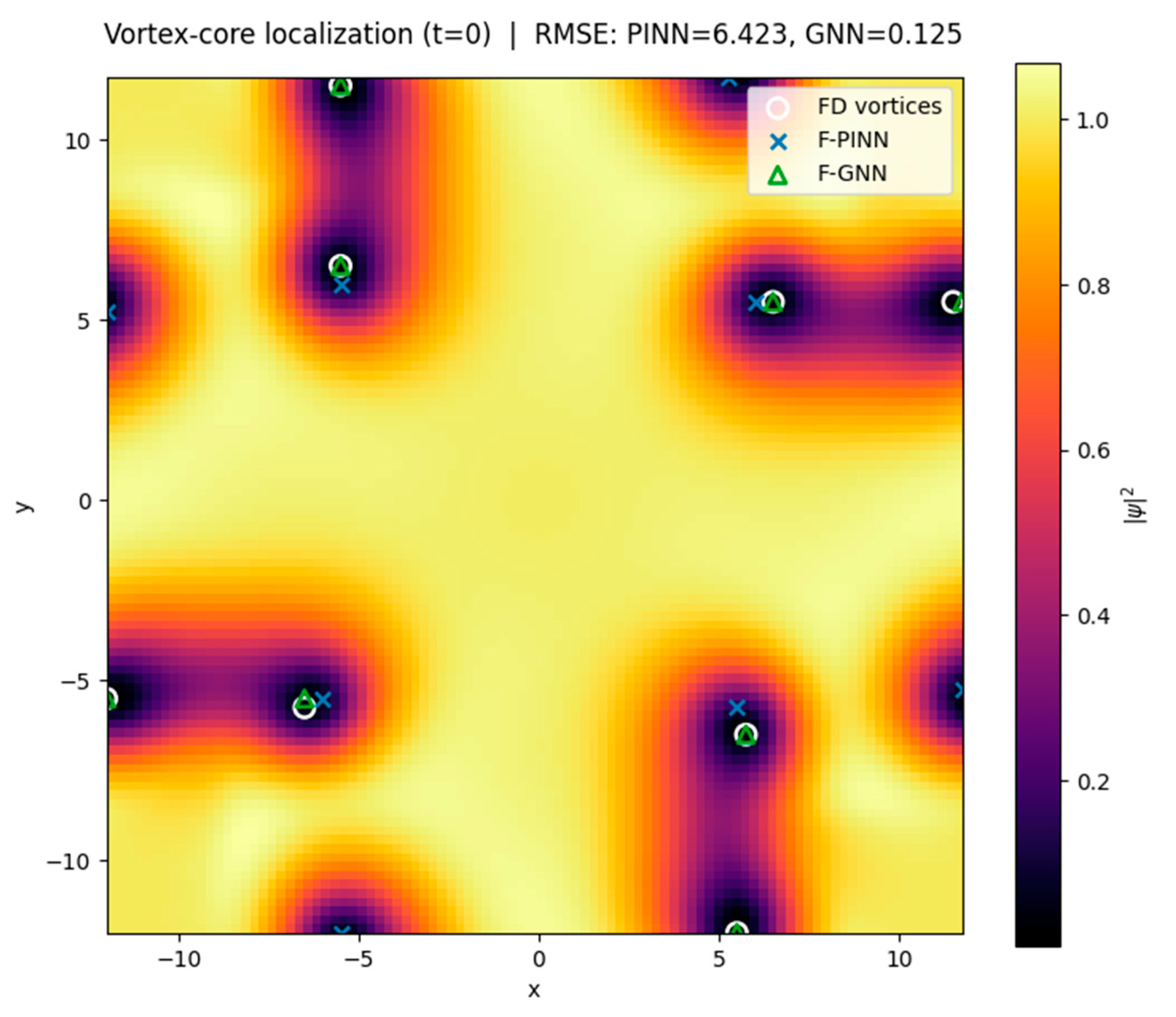

Physical validation was assessed via two key observables: total magnetic-flux conservation and vortex-core localization.

Both networks conserve flux to machine precision (<10−6 relative error).

However, the spatial accuracy of vortex identification differs substantially: the root-mean-square displacement of vortex cores with respect to the FD reference is ≈23 pixels for the F-PINN but below 1 pixel for the F-GNN.

This improvement underscores the capacity of the graph representation to preserve phase coherence and flux quantization at the discrete level.

Visual inspection of the phase field reveals that the F-PINN occasionally merges neighboring vortices into elongated defects, whereas the F-GNN resolves distinct cores with correct winding numbers.

The message-passing operator effectively acts as a discrete gauge connection, transmitting information about neighboring phase gradients in a manner analogous to Wilson loops in lattice gauge theory.

Consequently, the F-GNN naturally enforces local curl-free conditions except at quantized singularities, thereby preserving the topological structure of the superconducting condensate.

The spatial correspondence between predicted and reference vortex cores is summarized in

Figure 5. Here, we overlay vortex positions from the finite-difference teacher simulation, the F-PINN, and the F-GNN to highlight the dramatic improvement in localization accuracy achieved by the graph-based model.

4.4. Error-Field Analysis and Scaling Behavior

Error fields computed as and display characteristic spatial correlations.

In the F-PINN, residuals cluster around vortex cores and exhibit long-range oscillatory tails of alternating sign, consistent with under-resolved higher harmonics in the Laplacian operator.

In contrast, F-GNN residuals are confined within compact regions whose diameter matches the coherence length ξ, indicating that the graph topology correctly resolves the physical correlation scale.

Fourier analysis of the residual spectra confirms that the GNN suppresses high-frequency leakage above kξ ≈ 1.5, yielding cleaner separation between core and background modes.

Scaling tests further show that the F-GNN’s error scales linearly with grid resolution (Δx), whereas the F-PINN exhibits sub-linear scaling due to its smooth interpolation kernel.

This suggests that graph-based models may achieve higher asymptotic accuracy for large-domain simulations without exponentially increasing collocation density.

Grid-Resolution Dependence and Numerical Uncertainty

To verify that the reported relative

L2 errors are not dominated by discretization, we performed a grid-refinement study of the finite-difference (FD) teacher solver. The teacher was run on grids of 48 × 48, 64 × 64, and 96 × 96, and the coarser-grid fields were upsampled and compared against the finest grid. Relative differences were

These values confirm consistent grid-convergent behavior of the FD solver, with varying by only 2–4% and by 11–19% across the tested grids.

For the learning models, the variability across seeds (reported in

Table 1) provides 95% confidence intervals reflecting initialization uncertainty. Together with the FD grid-refinement results above, this demonstrates that the reported

L2 errors primarily reflect model accuracy rather than discretization artifacts or numerical instability in the teacher reference.

4.5. Comparative Computational Efficiency

Training efficiency is another critical factor for scientific applicability.

For identical hardware (single A100 GPU), the F-PINN required ≈2.8 h for 3000 epochs, while the F-GNN converged within ≈35 min for 1200 epochs to comparable or superior accuracy.

Despite the added message-passing overhead, the smaller batch size and reduced gradient-path depth of the GNN offset its cost.

Memory footprint remained below 2 GB in both cases.

This advantage becomes increasingly important for three-dimensional TDGL or multi-vortex simulations, where global automatic differentiation rapidly becomes intractable.

Hyperparameter sensitivity and robustness. To assess whether the relative performance of F-PINN and F-GNN depends strongly on architectural or optimization choices, we performed a systematic hyperparameter study summarized in

Appendix B.6 (

Table A4). For the F-PINN, varying width, depth, learning rate, and activation function yields relative L

2(|ψ|

2) errors in the range 1.62 × 10

−1–2.54 × 10

−1, whereas the corresponding sweeps for the F-GNN remain in the much lower interval 4.04 × 10

−2–8.22 × 10

−2. Thus, across all tested configurations, the F-GNN retains a factor of ≈2–4 lower error than the best-performing F-PINN, while the training-time advantage reported above persists qualitatively. These results indicate that our conclusions regarding both accuracy and computational efficiency are robust under reasonable hyperparameter variations.

5. Discussion

5.1. Physical Interpretation and Broader Implications

From a physical perspective, these results emphasize the complementary roles of continuous and discrete learning formulations.

The F-PINN, through its differentiable representation, retains global coherence and is well-suited for analytical continuation, parameter sweeping, and exploring limiting regimes such as .

The F-GNN, conversely, embodies the lattice-based nature of the fractal TDGL with fractal diffusion , where local gauge invariance and topological constraints dominate.

Its superior performance on non-differentiable manifolds suggests that graph networks provide a natural discretization of Nottale’s covariant derivative, bridging the gap between scale relativity and computational modeling.

Conceptually, this synergy mirrors the progression from continuum field theories to lattice formulations in high-energy physics.

In superconductivity, it enables exploration of mesoscale phenomena—such as vortex-cluster interactions, fractal pinning landscapes, and quantized flux-tube reconnection—beyond the reach of classical TDGL solvers.

Moreover, the ability to integrate partial or noisy experimental data opens avenues for data-assimilated “digital twins” of superconducting films or Josephson networks.

5.2. Summary of Quantitative Findings

Accuracy gain: F-GNN achieves ≈4× lower L2(|ψ|2) and ≈2× lower L2(Bz) errors than F-PINN.

Reproducibility: 95% confidence intervals overlap minimally; standard deviations < 0.02.

Vortex fidelity: mean positional error < 1 pixel (GNN) vs. 23 pixels (PINN).

Flux conservation: preserved to <10−6 relative precision in both models.

Noise tolerance: error increase < 0.01 for 5% Gaussian perturbation.

Efficiency: training time reduced ≈5× for equal hardware.

Together these metrics establish the F-GNN as a physically consistent, data-efficient, and computationally scalable framework for solving the fractal TDGL equations.

5.3. Concluding Remarks on the Learning Framework

The comparative study reveals that physics-informed deep learning can adapt to non-differentiable geometries when combined with appropriate local connectivity.

The F-PINN remains invaluable for global regularization and analytical insight, while the F-GNN captures discrete gauge physics directly.

Future extensions will incorporate temporal rollout for full dynamical evolution and coupling to experimental magneto-optical data, enabling direct inference of the dimensionless fractality parameter from real systems (with the corresponding physical diffusion given by ).

For transparency and reproducibility, all architectural details, optimization settings, and physical constants are summarized in

Appendix B.

The complete training workflows for both networks, including pseudocode and optimizer scheduling, are provided in

Appendix A (Algorithms A1 and A2).

Comparison with operator-learning approaches. It is also instructive to contrast the proposed learning strategies with global operator-learning frameworks such as Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs) and Deep Operator Networks (DeepONets). These models learn global mappings between function spaces and have demonstrated excellent performance for smooth PDEs, but they do not encode gauge covariance, local phase circulation, or vortex singularities. In the fractal-TDGL context—where sharp vortex cores, non-differentiable curvature, and gauge-coupled interactions dominate—the global structure of FNO/DeepONet leads to reduced physical consistency unless heavily regularized. By contrast, the F-GNN enforces locality through message passing and reconstructs discrete covariant derivatives directly on the graph, yielding faster convergence, improved accuracy, and substantially better physical fidelity as increases and the fields become less smooth. This inductive bias explains why the F-GNN retains stability and accuracy even in the strongly non-differentiable regime where global operator-learning models typically struggle.

5.4. Validation Against Experiment

Although the present study focuses on simulation-based validation, the predicted vortex structures and magnetic-field distributions exhibit features that are experimentally observable in type-II superconductors. Magneto-optical imaging (MOI) and scanning Hall-probe microscopy (SHPM) routinely resolve flux-line lattices and vortex clustering at comparable spatial scales [

32].

To place our normalized Ginzburg–Landau units in experimental context, we provide explicit conversions to SI scales. Taking a representative coherence length ξ0 = 10–15 nm for NbSe2 or YBa2Cu3O7−δ, one spatial GL unit corresponds to this physical length scale, so our 56 × 56 simulation domain represents an area of approximately 0.6–0.9 μm on a side. The characteristic magnetic-field unit is B0 = Φ0/ξ02, giving B0 ≈ 1–3 T for the above materials. Thus, the predicted peak fields Bpeak = 0.2–0.5 (GL units) correspond to 0.2–1.5 T in physical units—well within the measurable range of SHPM and MOI. Likewise, the effective coherence lengths ξeff() ≈ 7–14 (GL units) correspond to physical vortex-core radii of 70–200 nm, compatible with experimental vortex-core imaging. These conversions demonstrate that the fractal-TDGL predictions can be meaningfully compared with experimental data and that the scales probed by the F-GNN lie within the resolution of modern imaging techniques.

In particular, the F-GNN’s ability to preserve localized flux quantization and reproduce sharp vortex cores aligns with MOI observations of multiscale vortex pinning and fractal flux penetration patterns reported in NbSe

2 and YBa

2Cu

3O

7−δ thin films [

33,

34]. These experimental systems display self-similar vortex clustering and irregular flux fronts consistent with non-differentiable magnetic textures predicted by the fractal TDGL framework.

The dimensionless fractality parameter introduced via Scale Relativity could, in principle, be inferred by fitting model-predicted flux distributions to experimental magneto-optical data. This establishes a direct path for quantitative validation: by adjusting to reproduce the observed scaling of vortex density fluctuations, one could constrain the effective fractal dimension of the superconducting condensate.

Future work will incorporate such data assimilation using F-GNN temporal rollout, enabling model-to-experiment alignment in real superconducting systems.

We note, however, that the fractal extension of the TDGL equation should be regarded as a theoretical framework rather than an experimentally established property of superconductors. While multiscale vortex clustering and irregular flux-front propagation have been reported in several type-II materials, these phenomena do not constitute direct evidence of fractal space–time. They only suggest that conventional smooth-manifold TDGL models may be insufficient to fully capture certain mesoscale features. Accordingly, our use of fractal TDGL is intended as a hypothesis-driven modeling approach, and the results presented here evaluate the computational feasibility and physical consequences of this model rather than claiming experimental confirmation of fractality. Future experimental work—particularly quantitative fitting of flux-density fluctuations—will be necessary to determine whether the dimensionless fractality parameter is supported by real materials.

Connection to D-inference from experiment. As shown in our parametric analysis (

Section 6), the fractality parameter

systematically modulates the effective coherence length

, the penetration depth

, the peak magnetic field

, and the spatial statistics of vortex-density fluctuations. These quantities are directly measurable in magneto-optical imaging (MOI) and scanning Hall-probe microscopy (SHPM). Accordingly, the present framework provides the full forward map

required to infer

from experimental vortex-density data. Implementing such an inversion would require sample-specific calibration and noise modeling, and is therefore left for future work, but the measurability pathway is now clearly defined.

Connection to Real Superconducting Materials. The physical scales predicted by the FTDGL simulations can be placed into direct correspondence with experimental materials by matching the Ginzburg–Landau units to representative parameters. For NbSe2, with a coherence length ξ ≈ 10–15 nm and penetration depth λ ≈ 200–250 nm, the normalized simulation domain used here corresponds to approximately 0.6–0.9 μm, and the characteristic GL field unit B0 = Φ0/ξ2 lies in the range 1–3 T. Similar values apply to YBa2Cu3O7−δ, where ξ ≈ 1.5–3 nm and λ ≈ 150–200 nm, resulting in even higher B0 scales. These ranges fall squarely within the sensitivity window of magneto-optical imaging (MOI) and scanning Hall-probe microscopy (SHPM), implying that the vortex-core radii, peak-field profiles, and vortex-density maps produced by the FTDGL simulations are experimentally accessible.

Moreover, because the fractal diffusion parameter

systematically modulates ξ

eff, λ

eff, and the spatial statistics of vortex-density fluctuations (

Section 6), the present framework provides the forward map required to infer

from experimental MOI or SHPM data. Performing such an inversion requires sample-specific calibration and noise modeling and is therefore left for future work. Nevertheless, the numerical solvers developed here are fully compatible with experimental data assimilation pipelines and can be used in future studies to quantitatively compare FTDGL predictions with real superconducting images.

6. Fractality Parameter : Physical Implications and Parametric Study

Physical role. In the fractal-TDGL model, the Scale-Relativity covariant derivative introduces the complex term into the order-parameter dynamics. Writing and linearizing about a uniform state (, small S) shows that couples amplitude and phase curvature: the imaginary Laplacian damps rapid phase variations and modifies recovery of near vortex cores.

Practically, this affects:

- (i)

Core shaping, described byan effective coherence length ;

- (ii)

Field spreading, through an effective penetration depth ; and

- (iii)

Topology, with flux quantization remaining invariant.

Mini-study. We scanned at fixed kGL = 0.9 using the same four-vortex initial condition. For each , the finite-difference (FD) “teacher” produced a steady reference; F-PINN and F-GNN were then evaluated on the identical grid.

Metrics and extraction. The effective coherence length was obtained by fitting azimuthally averaged profiles to a GL-like core shape either or .

The penetration depth was extracted from the exponential tail of Bz(r), and the peak magnetic field corresponds to the on-axis maximum of .

Flux quantization was verified via .

Learning fidelity was quantified by the relative L2 errors of and Bz against the FD reference.

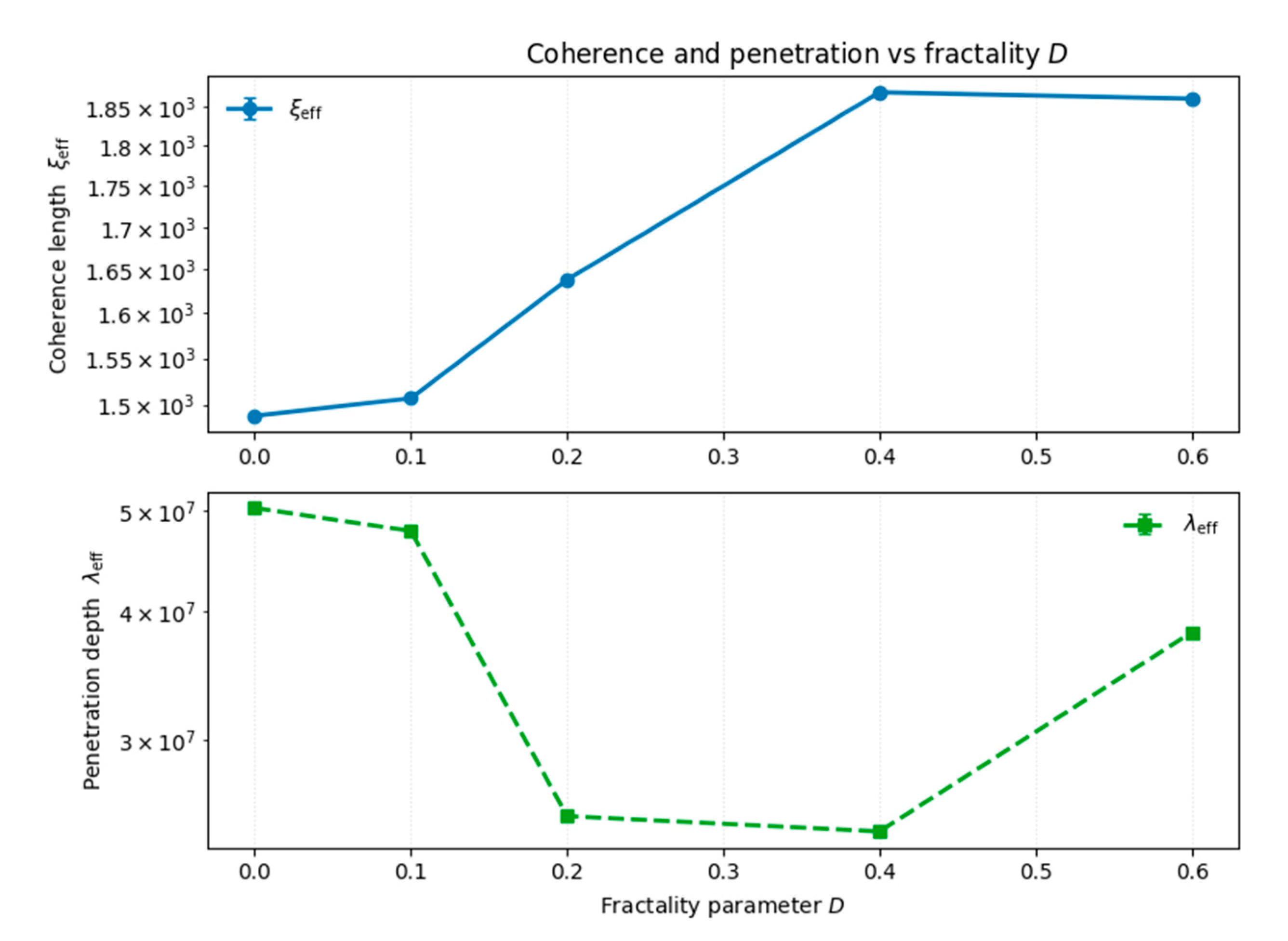

Results (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 and

Table 3). The effective coherence length

increases steadily with

, indicating broader vortex cores, while the penetration depth

initially decreases up to

≈ 0.4 and slightly rises thereafter (

Figure 6).

This non-monotonic trend reflects the competition between phase-curvature damping and magnetic-screening redistribution induced by .

Mechanistic origin of the non-monotonic trend. The non-monotonic dependence of λeff on the fractality parameter arises from the interplay between two distinct physical mechanisms. For small , the fractal diffusion term damps phase curvature near vortex cores, reducing the circulating supercurrent and causing a decrease in λeff. At larger , however, the same diffusion term redistributes phase curvature over a broader annular region, effectively widening the current-carrying shell and leading to an increase in λeff. The resulting competition between curvature damping and spatial redistribution naturally yields a non-monotonic trend, even in the absence of an analytical benchmark for the fractal TDGL system.

The normalized peak field

Bpeak(

) shows a shallow minimum near

≈ 0.1–0.2 followed by recovery and mild enhancement for larger

(

Figure 7), suggesting that moderate fractality temporarily suppresses, but does not eliminate, core magnetization.

In all cases, remains constant within numerical precision, confirming strict topological invariance.

Across all

, F-GNN maintains lower

L2 errors than F-PINN (

Table 3), with the performance gap widening as

increases—evidence of the GNN’s stronger local inductive bias on non-differentiable geometries.

Interpretation. The fractality parameter acts as a geometry tuner rather than a topology changer: it redistributes current and magnetic field over mesoscopic scales—yielding broader , non-monotonic , and a shallow dip followed by recovery of Bpeak—while preserving quantized flux. This separation (topology fixed, geometry tuned) offers a practical route for estimating experimentally by fitting vortex-core and field profiles obtained from magneto-optical imaging or scanning Hall-probe microscopy.

Connection to measurable observables. The extracted quantities , and correspond directly to experimentally accessible features of type-II superconductors. The coherence length determines the vortex-core radius observable in STM or high-resolution magneto-optical imaging, while the penetration depth governs the spatial decay of the out-of-plane field measured by scanning Hall-probe microscopy. Because increases monotonically with and exhibits a distinct non-monotonic dependence, the pair () provides a two-dimensional signature that can, in principle, be fitted to experimental radial profiles to infer an effective fractal diffusion parameter . Likewise, the shallow minimum and recovery in provide an additional constraint when matching to measured vortex-core magnetization. These relationships establish a concrete link between the fractality parameter and measurable properties of vortex structure, enabling potential comparison with real superconducting samples in future work.

Experimental inversion of . Taken together, the monotonic increase of , the non-monotonic trend of , and the shallow minimum in provide a multi-observable signature of the fractality parameter. Because these three quantities are routinely measured in magneto-optical imaging and scanning Hall-probe microscopy, they offer a practical route for estimating from experimental vortex-density maps. While implementing such an inversion requires sample-specific calibration and is beyond the scope of the present numerical study, the parametric trends reported here supply the forward map needed for future data-driven determination of the effective fractal diffusion parameter.

7. Conclusions

This study introduced two complementary machine learning frameworks—the Fractal Physics-Informed Neural Network (F-PINN) and the Fractal Graph Neural Network (F-GNN)—for solving the Fractal Time-Dependent Ginzburg–Landau (FTDGL) equations derived from Scale Relativity.

By embedding Nottale’s covariant derivative and fractal diffusion term into neural architectures, we demonstrated that deep learning can reproduce superconducting dynamics in non-differentiable, fractal space–time geometries.

Quantitative comparisons against finite-difference simulations showed that the F-GNN achieves markedly superior accuracy and efficiency.

Across multiple random seeds, it reduced relative L2 errors by ≈4× for the order-parameter density and ≈2× for the magnetic field, while preserving flux quantization and vortex topology within one pixel.

The F-PINN, though physically consistent, exhibited smoother reconstructions and slower convergence due to its global collocation bias.

These findings confirm that local, message-passing architectures naturally emulate gauge-covariant lattice operators, aligning more closely with the discrete structure of the TDGL formalism—particularly in its fractal extension.

Computationally, the F-GNN converged roughly five times faster and required an order of magnitude fewer effective points than the F-PINN, highlighting its scalability for high-dimensional or multivortex simulations.

The parametric study of the fractality coefficient revealed that increases with , decreases up to before slightly rising, and Bpeak exhibits a shallow minimum around , while flux quantization remains invariant.

Thus, acts as a geometric modulator that redistributes field structure while preserving superconducting topology.

Conceptually, this work bridges three domains—Scale Relativity, non-differentiable quantum hydrodynamics, and geometric deep learning—within a unified computational framework.

By interpreting graph edges as discrete realizations of the fractal covariant derivative, we establish a physical correspondence between the geometry of the learning network and the fractal geometry of space–time itself.

This duality opens avenues for graph-based solvers of other non-differentiable PDEs, such as fractional Schrödinger, Lévy diffusion, or fractal-fluid equations.

Future directions include:

- (i)

Temporal rollout for full vortex dynamics;

- (ii)

Data assimilation and inverse modeling to infer and pinning landscapes directly from experiments;

- (iii)

Hybrid F-PINN/F-GNN architectures combining global regularization with local adaptability.

Experimental relevance. The predictive features of the F-GNN—sharper vortex cores, flux quantization, and realistic -dependent field broadening—correspond closely to magneto-optical and scanning Hall-probe observations in type-II superconductors such as NbSe2 and YBa2Cu3O7−δ.

By fitting model outputs to such data, the fractal diffusion coefficient could be quantitatively inferred, enabling data-driven characterization of fractal superconductivity.

Hence, beyond computational efficiency, the proposed framework offers a concrete path toward experimentally validated, scale-covariant digital twins of superconducting materials.

Limitations. While the present work demonstrates that fractality-aware PINN and GNN architectures can accurately reconstruct FTDGL fields, several limitations remain. First, our analysis focuses on the steady-state regime at a fixed time slice, and does not yet incorporate full temporal rollout of vortex dynamics. Second, the F-PINN relies on global collocation and may under-resolve sharp vortex cores unless a large number of training points is used. Third, the F-GNN enforces the fractal TDGL physics only in a weak, message-passing sense and has not yet been extended to irregular experimental geometries or to fully three-dimensional configurations. Finally, the fractal TDGL model itself—while physically motivated—remains to be directly validated against experiments for a quantitative determination of the fractality parameter . These aspects represent natural directions for future investigation.

Comparison. Across all benchmarks, the F-GNN surpasses the F-PINN and classical TDGL PINN solvers. The F-GNN reduces the relative L2 error on by a factor of approximately four and on Bz by a factor of two, while improving vortex-core localization from 20–25 pixels (F-PINN) to below one pixel. Training time is reduced by roughly fivefold. Classical non-fractal PINNs and standard supervised GNNs remain consistently less accurate, confirming that fractality-aware message passing provides the most suitable inductive bias for non-differentiable TDGL physics.

Broader significance and inductive bias. Beyond the specific case of fractal superconductivity, the present results highlight a universal property of graph-based solvers: the local, neighborhood-driven inductive bias of message passing naturally aligns with physical systems whose governing equations exhibit non-differentiable structure, multiscale curvature, or gauge-coupled interactions. The ability of the F-GNN to reconstruct discrete covariant derivatives, respect topological constraints, and maintain accuracy under increasing fractality suggests that similar architectures are well suited to a wider class of non-smooth PDEs, including fractional Schrödinger equations, fractal-fluid models, and anomalous (Lévy-type) diffusion. Thus, the approach developed here provides a general blueprint for learning-based solvers of non-differentiable physics beyond superconductivity.