A Simple Method for Generating New Fractal-like Aggregates from Gravity-Based Simulation and Diffusion-Limited Aggregation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Classic Fractal-like Aggregate Construction Methods

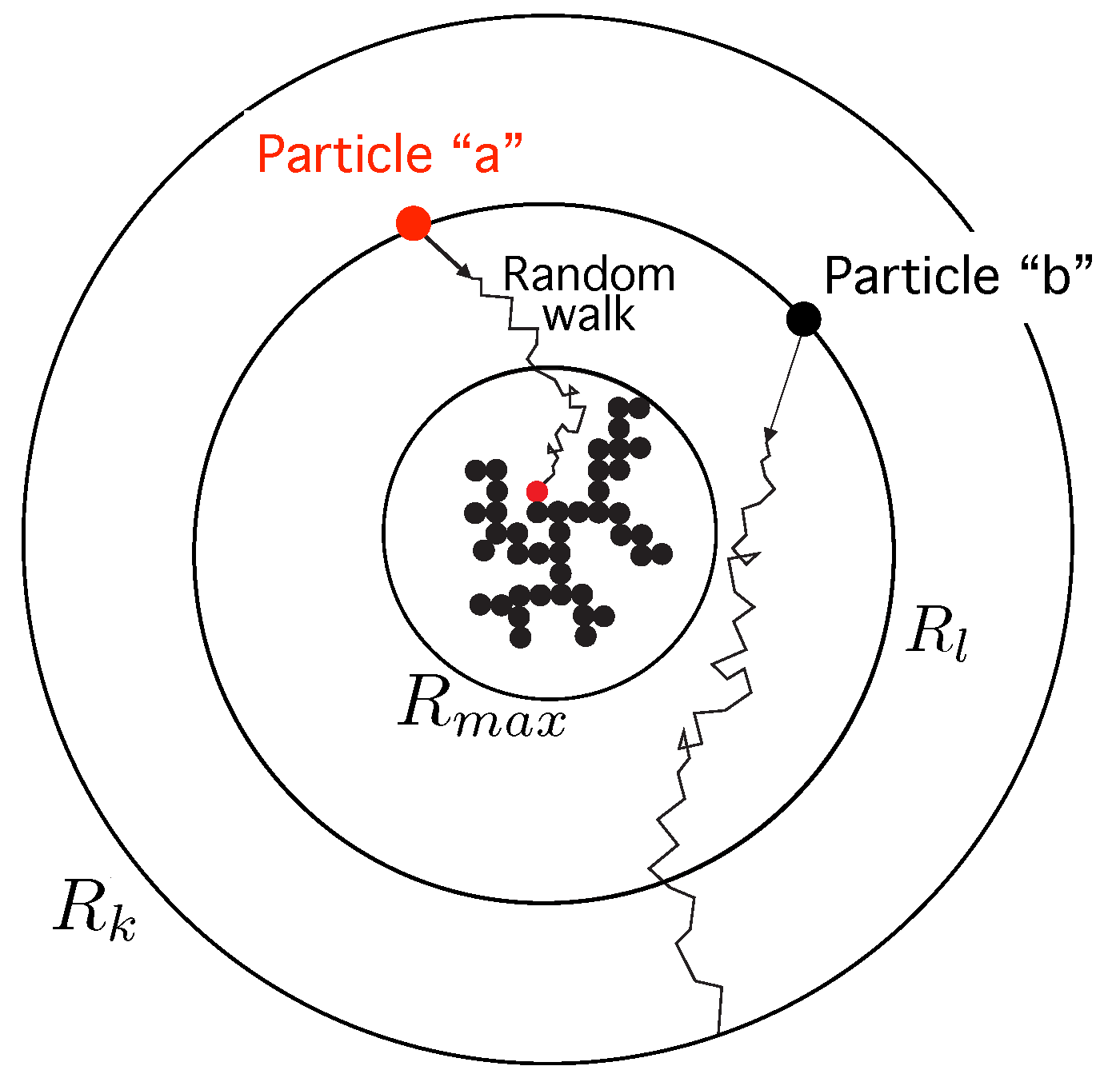

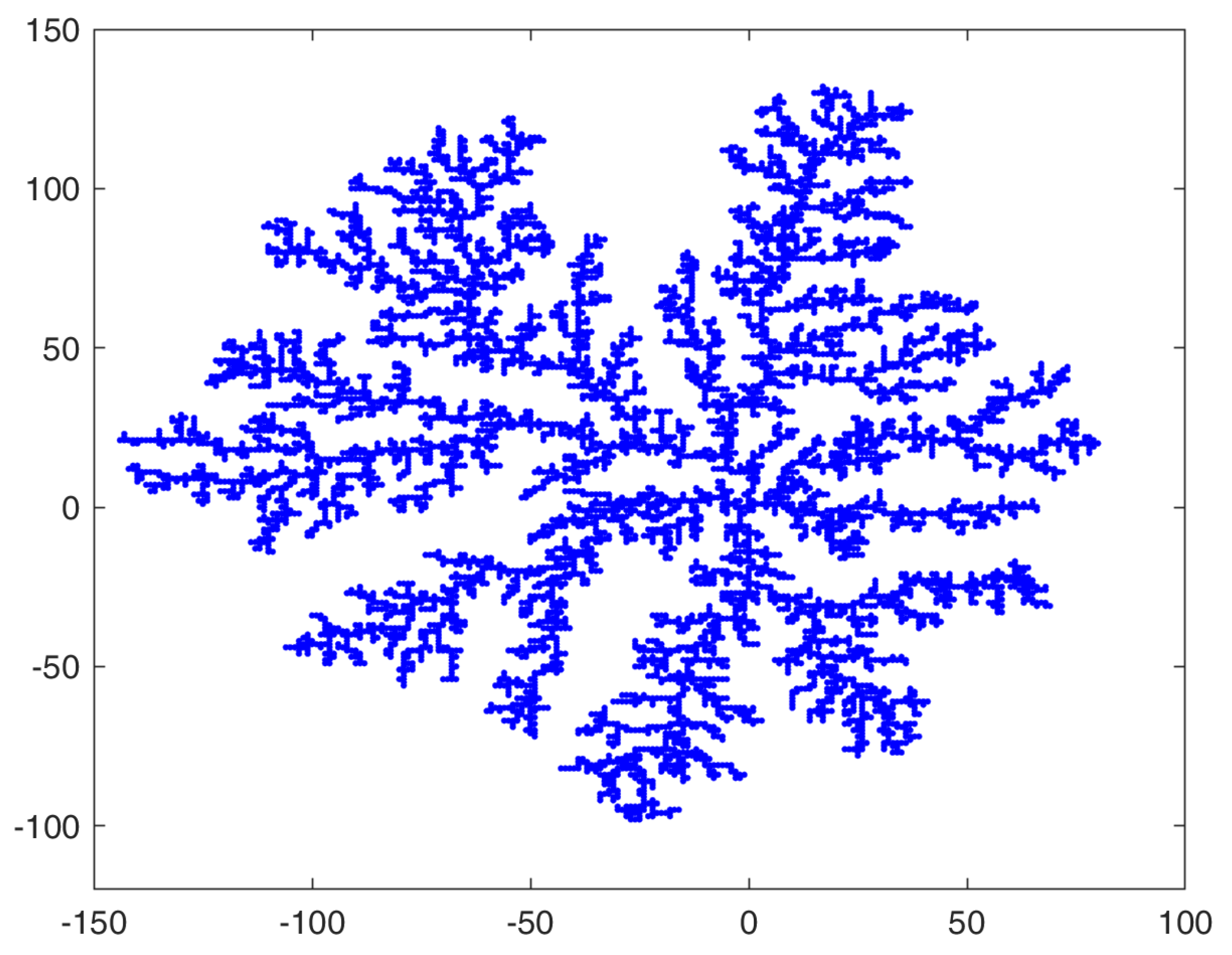

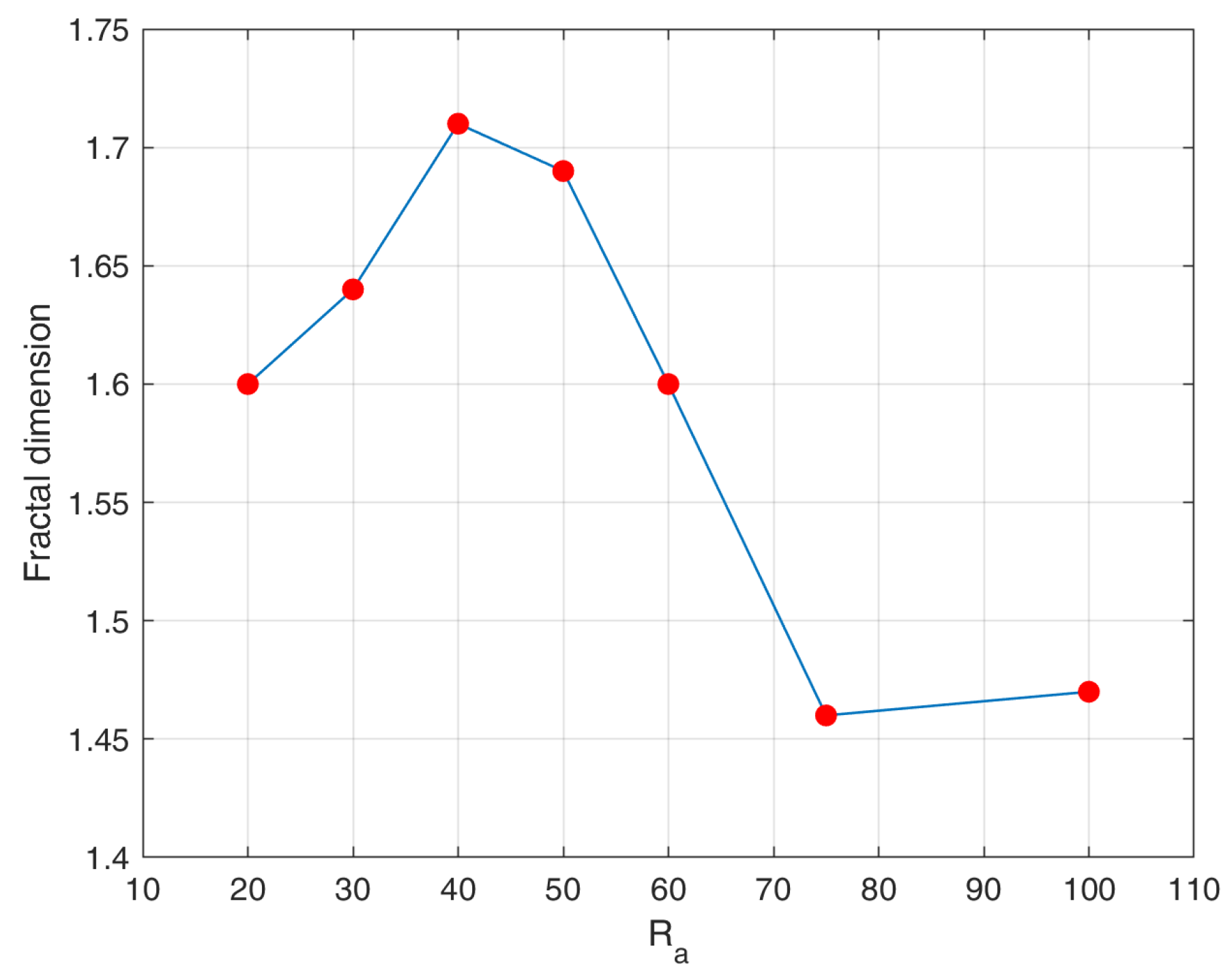

2.1. Diffusion-Limited Aggregation

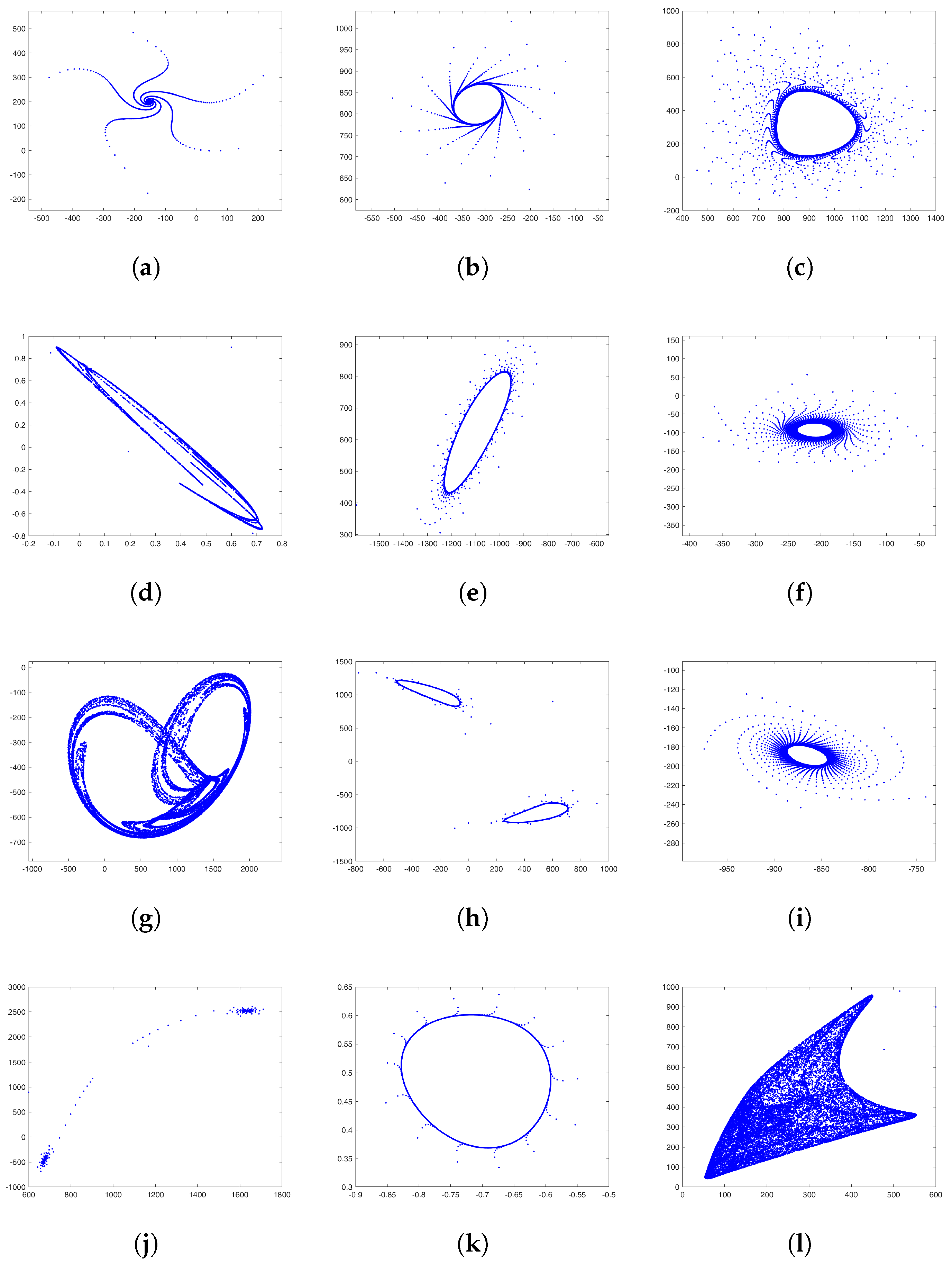

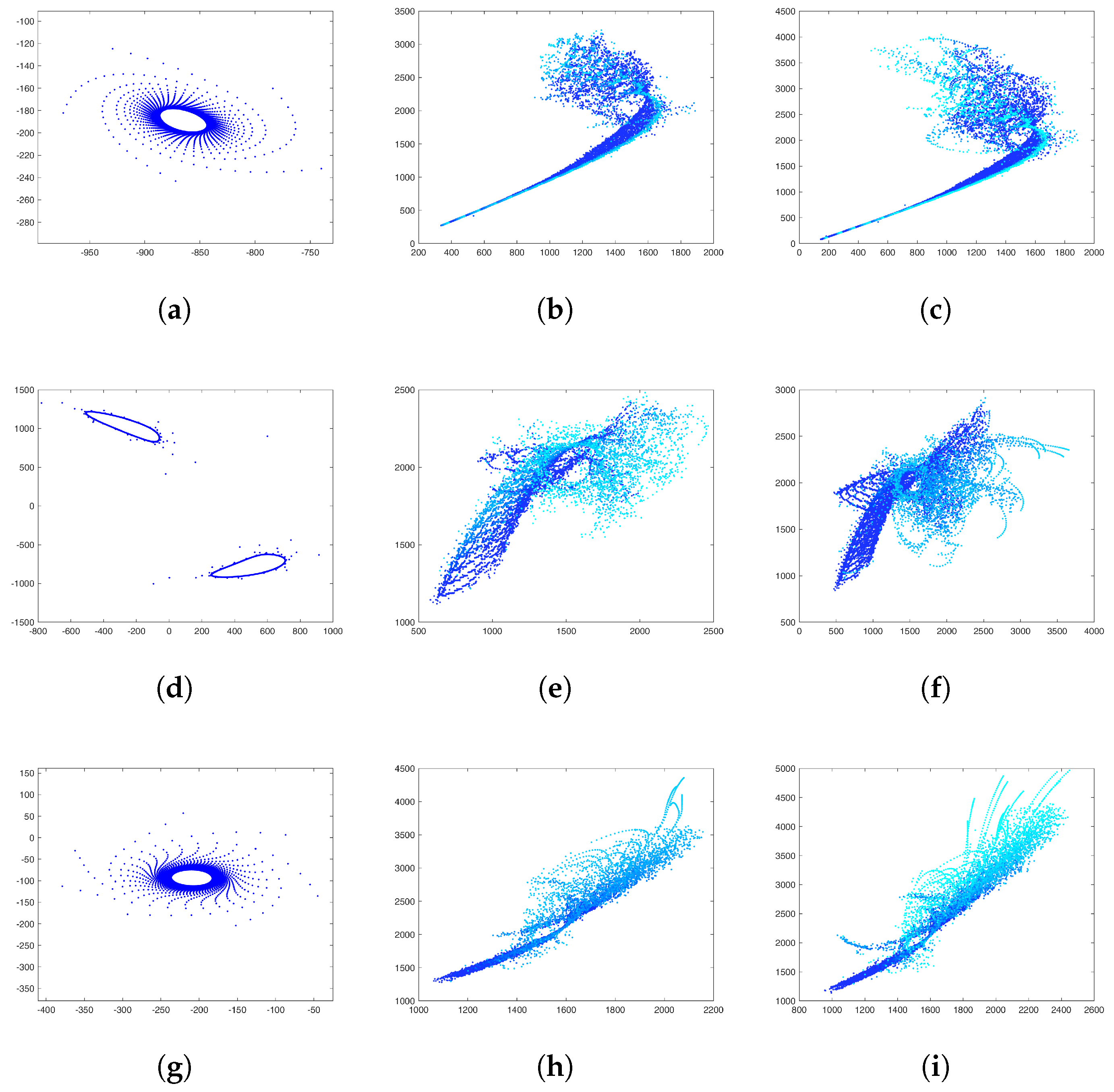

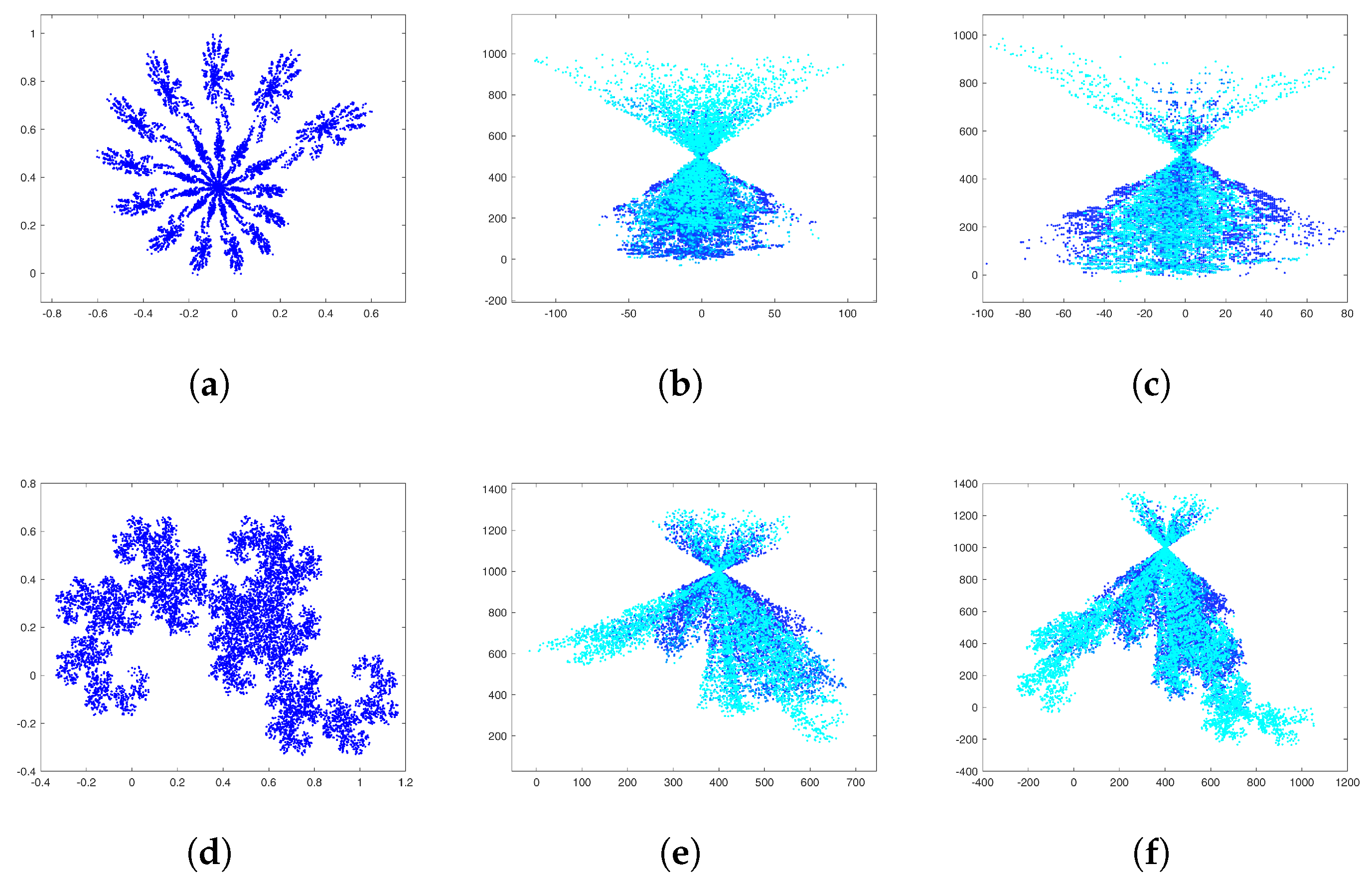

2.2. Strange Attractors

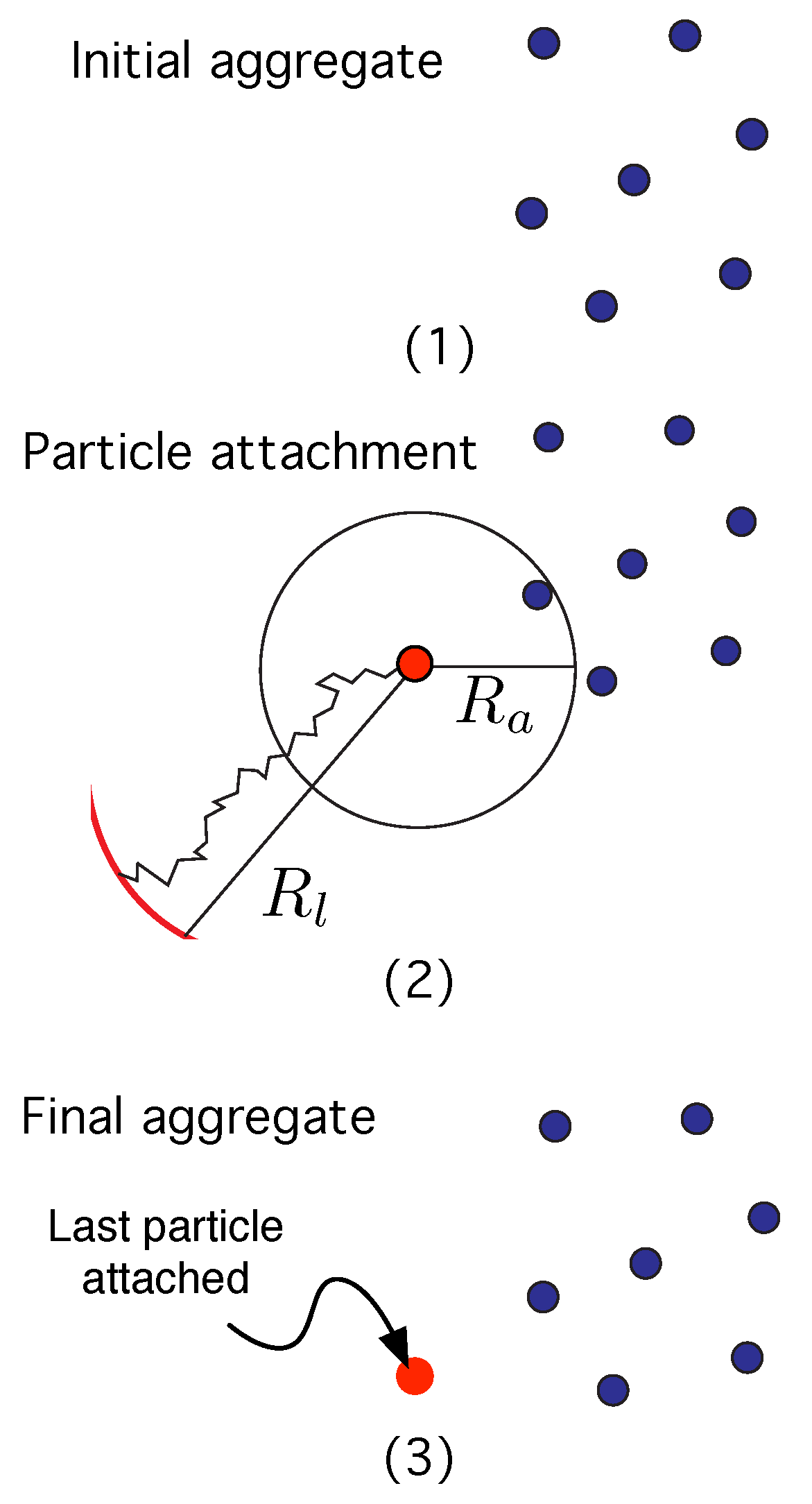

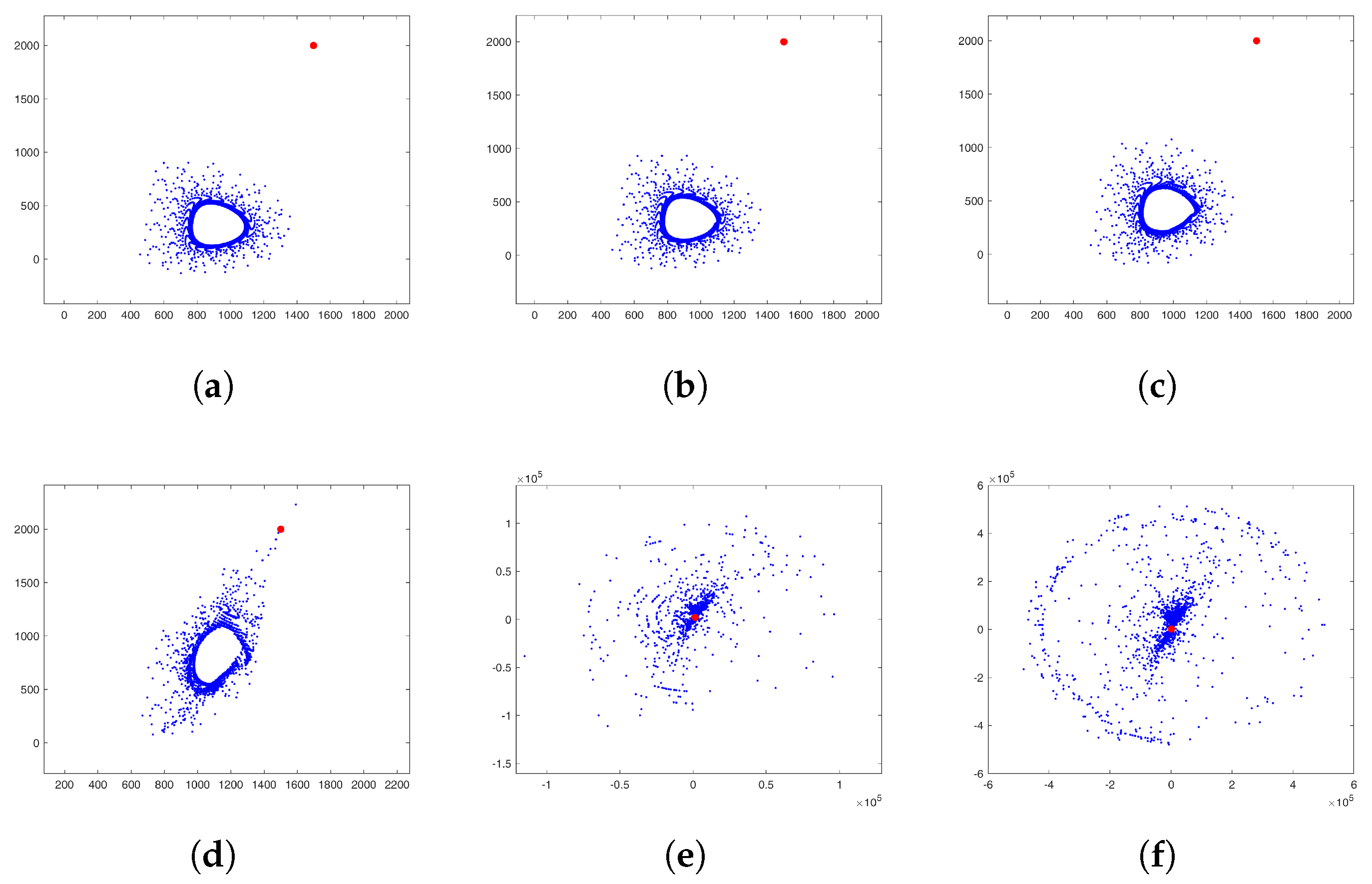

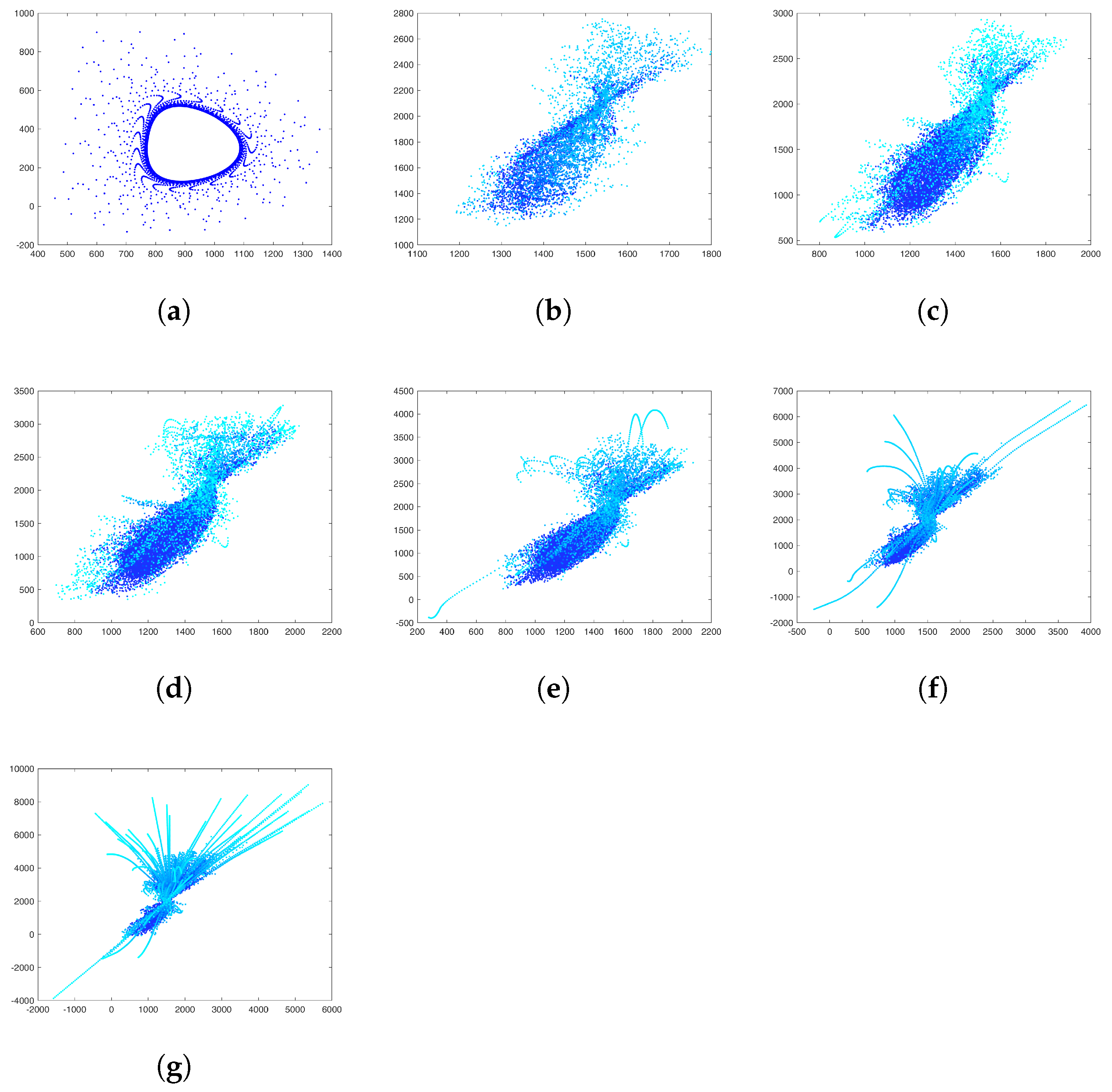

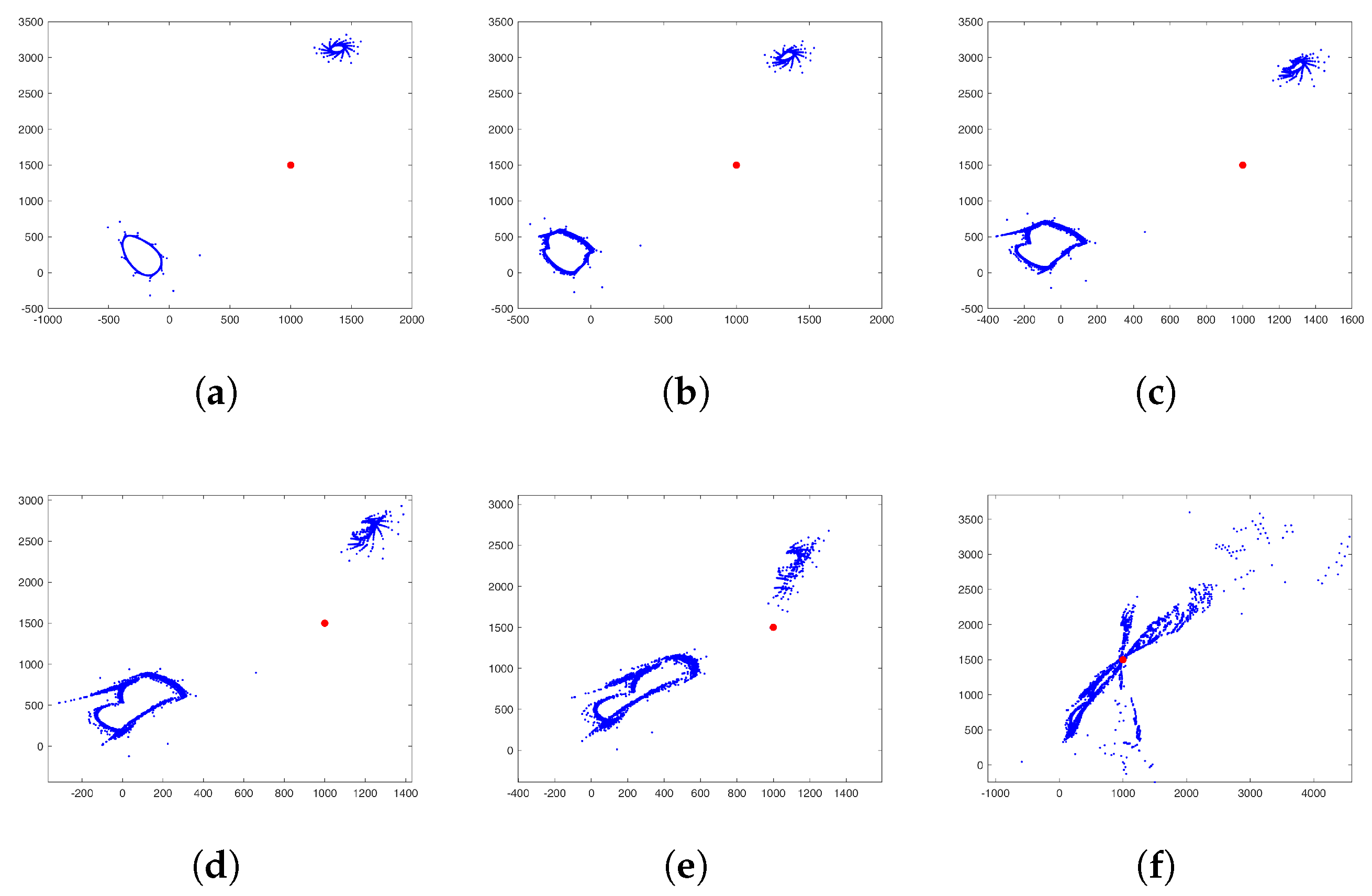

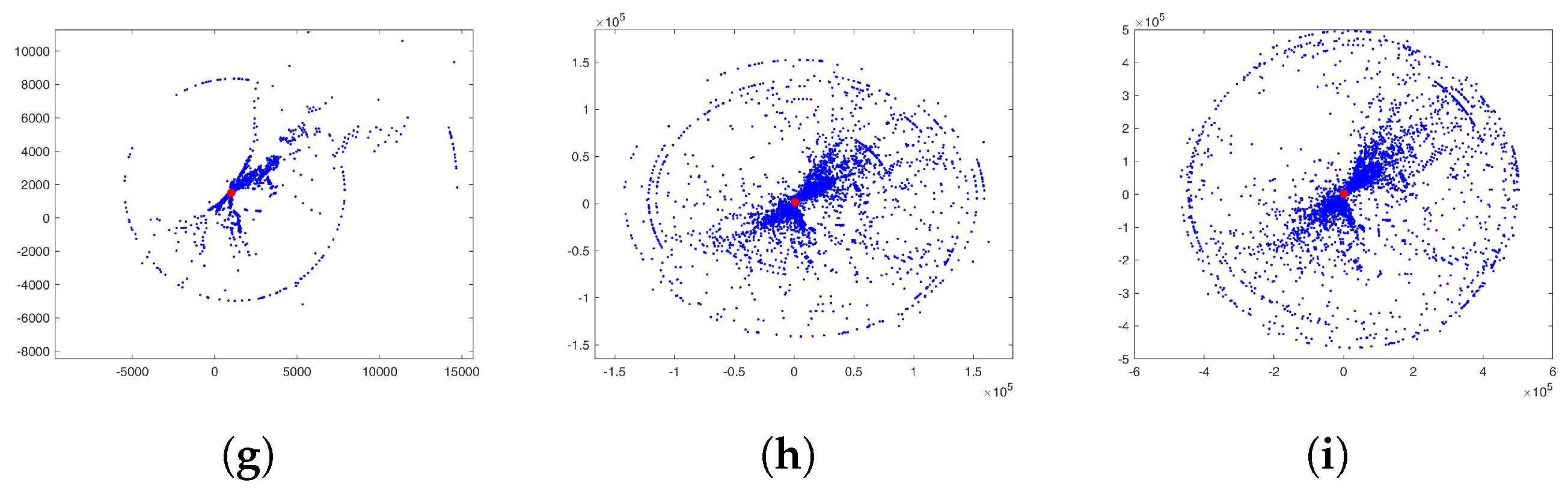

3. Construction of New Fractal Aggregates from Gravity DLA Simulation

| Algorithm 1 Pseudo-code of the Gravity-based DLA algorithm |

|

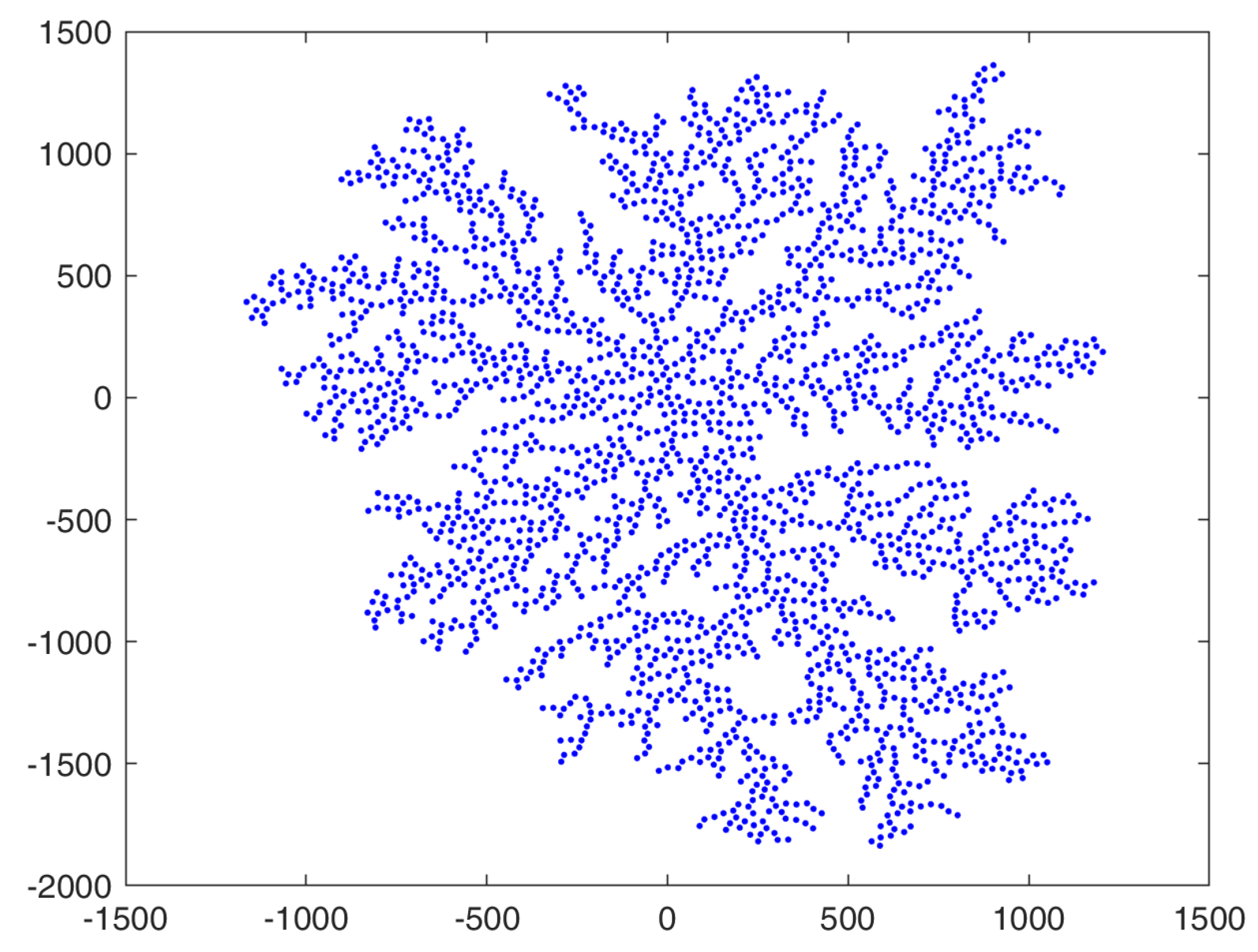

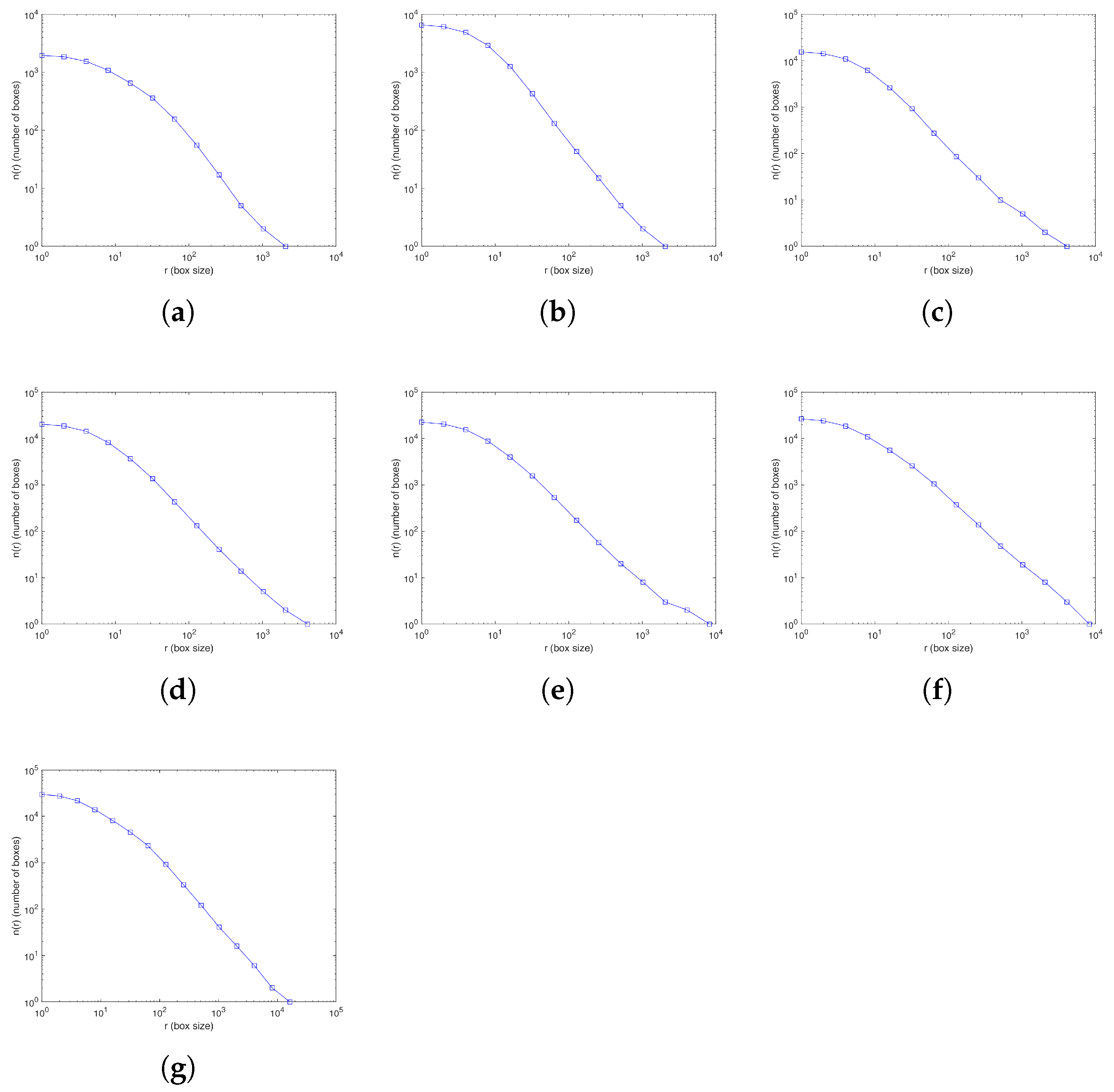

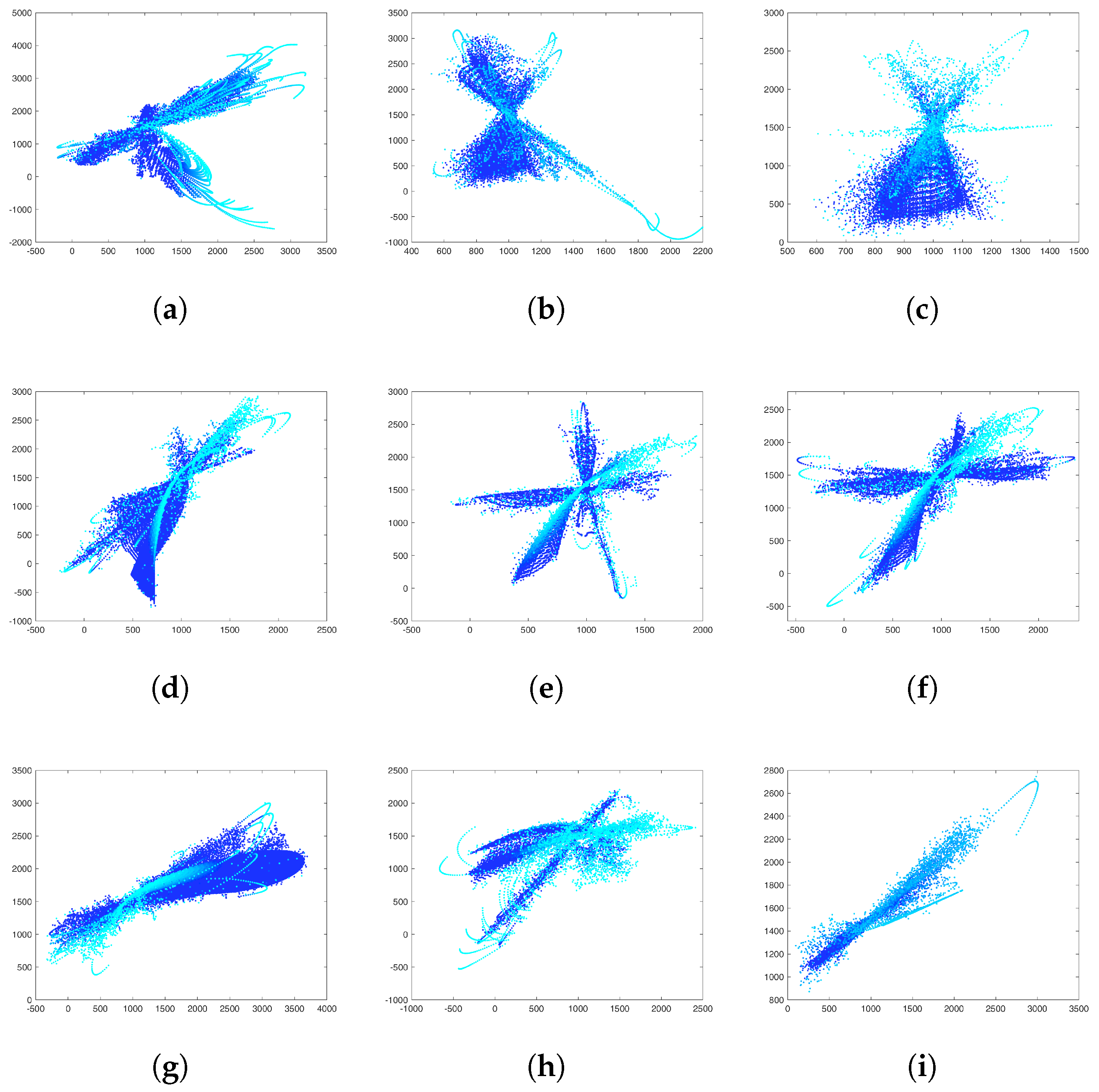

4. New Fractal-like Aggregates from Gravity-Based Simulation and DLA

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Strange Attractor Fractal Construction

Appendix A.2. IFS Fractal Construction

References

- Sander, L.M. Fractal growth processes. Nature 1986, 322, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meakin, P. The growth of fractal aggregates. In Time-Dependent Effects in Disordered Materials; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1987; pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Meakin, P. Fractals, Scaling and Growth Far from Equilibrium; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, T.A.; Sander, L.M. Diffusion-limited aggregation. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 27, 5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meakin, P. Formation of fractal clusters and networks by irreversible diffusion-limited aggregation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 51, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprott, J.C. Automatic generation of iterated function systems. Comput. Graph. 1994, 18, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, M.; Hutchinson, J.; Stenflo, Ö. A fractal valued random iteration algorithm and fractal hierarchy. Fractals 2005, 13, 111–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Chang, T.C.; Mao, Y.M. A kind of IFS fractal image generation method based on Markov random process. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Computation, Communication and Engineering (ICCCE), Nanping, China, 25–27 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X.; Bai, S.; Liu, C.; Chen, H.; Yan, Y. Algorithm of Controllable Fractal Image Based on IFS Code. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Computer Applications (ICPECA), Shenyang, China, 22–24 January 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 801–809. [Google Scholar]

- Grassberger, P.; Procaccia, I. Measuring the strangeness of strange attractors. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1983, 9, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassberger, P.; Procaccia, I. Characterization of strange attractors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 50, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprott, J.C. Strange Attractors: Creating Patterns in Chaos; M & T Books: New York, NY, USA, 1993; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer, A. Mathematical models for cellular interactions in development I. Filaments with one-sided inputs. J. Theor. Biol. 1968, 18, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.; Mishra, S. L-System Fractals; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 209. [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz, P.; Hanan, J. Lindenmayer Systems, Fractals, and Plants; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 79. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, J.L.; Rubiano, G.N.; Zlobec, B.J. Generating fractal patterns by using p-circle inversion. Fractals 2015, 23, 1550047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrl, L.; Soos, M.; Lattuada, M. Generation and geometrical analysis of dense clusters with variable fractal dimension. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 10587–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Sanz, S. Modern meta-heuristics based on nonlinear physics processes: A review of models and design procedures. Phys. Rep. 2016, 655, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, J. Fractals: The Patterns of Chaos: A New Aesthetic of Art, Science, and Nature; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Scotto Rosato, G. Fractal art. J. Sci. Commun. 2010, 9, A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, N. Creating Celtic art using fractal image generation. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia & Expo Workshops (ICMEW), Seattle, WA, USA, 11–15 July 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, A.; Nanda, M.N.; Chowdary, M.S.; Sajid, M. Fractals: An eclectic survey, part-I. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Nanda, M.N.; Chowdary, M.S.; Sajid, M. Fractals: An eclectic survey, part-II. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovill, C. Fractal Geometry in Architecture and Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Harrell, S.; Ji, X. Computational aesthetics: On the complexity of computer-generated paintings. Leonardo 2012, 45, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. Fractal patterns in nature and art are aesthetically pleasing and stress reducing. Conversat. 2017, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractal geometry: What is it, and what does it do? Proc. R. Soc. London. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 1989, 423, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, J. Benoit Mandelbrot and fractals in art, science and technology. Leonardo 2011, 44, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, B.; Mishra, J. Generation of 3D Fractal Images for Mandelbrot and Julia Sets. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Technol. 2010, 1, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ji, M. Research of fractal artistic graphics generation method. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Intelligent Transportation, Big Data and Smart City, Halong Bay, Vietnam, 19–20 December 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 609–612. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Pan, Z.; Fu, W.; Cheng, X. Fractal generation method based on asymptote family of generalized Mandelbrot set and its application. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2017, 10, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwun, Y.C.; Shahid, A.A.; Nazeer, W.; Abbas, M.; Kang, S.M. Fractal generation via CR iteration scheme with s-convexity. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 69986–69997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassaddiq, A.; Tanveer, M.; Azhar, M.; Arshad, M.; Lakhani, F. Escape criteria for generating fractals of complex functions using DK-iterative scheme. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Prajapati, D.J.; Tomar, A.; Gdawiec, K. Generation of Mandelbrot and Julia sets for generalized rational maps using SP-iteration process equipped with s-convexity. Math. Comput. Simul. 2024, 220, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwun, Y.C.; Tanveer, M.; Nazeer, W.; Abbas, M.; Kang, S.M. Fractal generation in modified Jungck–S orbit. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 35060–35071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassaddiq, A.; Tanveer, M.; Zubair, M.; Arshad, M.; Cattani, C. On the Application of Mann-Iterative Scheme with h-Convexity in the Generation of Fractals. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, M.; Henry, B. Diffusion-limited aggregation with Eden growth surface kinetics. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1994, 203, 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Xia, H. Crossover effects and dynamic scaling properties from Eden growth to diffusion-limited aggregation. Phys. Lett. A 2024, 508, 129494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Sanz, S.; Cuadra, L. Hybrid L-systems–diffusion limited aggregation schemes. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 514, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Sanz, S.; Cuadra, L. Multi-fractal multi-resolution structures from DLA–Strange Attractors Hybrids. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2020, 83, 105092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z. The growth simulation of pine-needle like structure with diffusion-limited aggregation and oriented attachment. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 22946–22950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, T.C. Diffusion-limited aggregation: A model for pattern formation. Phys. Today 2000, 53, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, H.; Coniglio, A.; Havlin, S.; Lee, J.; Schwarzer, S.; Wolf, M. Diffusion limited aggregation: A paradigm of disorderly cluster growth. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1994, 205, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S., Jr.; Alves, S.; Brito, A.F.; Moreira, J. Morphological transition between diffusion-limited and ballistic aggregation growth patterns. Phys. Rev. E—Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2005, 71, 051402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, H.E.; Bunde, A.; Havlin, S.; Lee, J.; Roman, E.; Schwarzer, S. Recent approaches to understanding diffusion limited aggregation. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1990, 168, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Sano, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Honjo, H.; Sawada, Y. Fractal structures of zinc metal leaves grown by electrodeposition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984, 53, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Fujikawa, H. Diffusion-limited growth in bacterial colony formation. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1990, 168, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserta, F.; Stanley, H.; Eldred, W.; Daccord, G.; Hausman, R.; Nittmann, J. Physical mechanisms underlying neurite outgrowth: A quantitative analysis of neuronal shape. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salcedo-Sanz, S.; Cuadra, L. Quasi scale-free geographically embedded networks over DLA-generated aggregates. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 523, 1286–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Mizrachi, A.; Procaccia, I.; Grassberger, P. Characterization of experimental (noisy) strange attractors. Phys. Rev. A 1984, 29, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, M.F. Fractals Everywhere; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, R.F. Random fractals: Characterization and measurement. In Scaling Phenomena in Disordered Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Block, A.; Von Bloh, W.; Schellnhuber, H. Efficient box-counting determination of generalized fractal dimensions. Phys. Rev. A 1990, 42, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiberg, U.; Kohl, S. Box dimension of fractal attractors and their numerical computation. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2021, 95, 105615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Singh, A.K.; Kolan, S.R.; Tsotsas, E. Investigation of the relationship between the 2D and 3D box-counting fractal properties and power law fractal properties of aggregates. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salcedo-Sanz, S.; Álvarez-Couso, P.; Castelo-Sardina, L.; Pérez-Aracil, J. A Simple Method for Generating New Fractal-like Aggregates from Gravity-Based Simulation and Diffusion-Limited Aggregation. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120791

Salcedo-Sanz S, Álvarez-Couso P, Castelo-Sardina L, Pérez-Aracil J. A Simple Method for Generating New Fractal-like Aggregates from Gravity-Based Simulation and Diffusion-Limited Aggregation. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(12):791. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120791

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalcedo-Sanz, Sancho, Pablo Álvarez-Couso, Luis Castelo-Sardina, and Jorge Pérez-Aracil. 2025. "A Simple Method for Generating New Fractal-like Aggregates from Gravity-Based Simulation and Diffusion-Limited Aggregation" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 12: 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120791

APA StyleSalcedo-Sanz, S., Álvarez-Couso, P., Castelo-Sardina, L., & Pérez-Aracil, J. (2025). A Simple Method for Generating New Fractal-like Aggregates from Gravity-Based Simulation and Diffusion-Limited Aggregation. Fractal and Fractional, 9(12), 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9120791