Using Fractal Thinking to Determine Consumer Patterns Necessary for Organizational Performance: An Approach Based on Touchpoint Pilot Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Customer Journey Mapping and Touchpoint Intensity

- -

- -

- -

- Linear attribution—Each touchpoint of the customer receives equal credit to the final purchase; if there are five channels, each receives 20% in the final purchase.

- U-shaped—In this model, some channels are more important than others. The most important are the first and the last touch, receiving 40%, and the others an equal weight.

- W-shaped—From the total channels, the model considers some more important (first, middle, and last) and the others not. The core ones receive 30% and the others 5% credit.

- Time decay—In this model, more importance is offered to the ones found closer to the final purchase. Last-touch attribution works well for digital campaigns because the customer actions happen so quickly after the campaign [68], which is the reason for analyzing this type of touchpoint in our study.

- a

- The characteristics of using a touchpoint:

- b

- The benefits resulting from using a touchpoint:

- -

- For the organization: easy transfer of experience into the new touchpoint in sustainability and moral norms [71] to create, maintain, or design high-quality touchpoint combinations [72], business smarts and awareness, natural leadership, ability to influence, to persuade, to follow, or to be flexible, raw talent to create something new, and speed, accuracy, connection to brand, the skills of the selling team, the visual marketing tools, and authenticity through the use of AI for young generations [70].

- -

2.2. Touchpoint Indicators and the Value of a Customer

- -

- -

- A positive impact: A greater CC will lead to higher profitability, provide stable sales channels, and guarantees efficiency, significant cash flow, and efficient production. Because the company has an asymmetric dependence on influential customers, losing them would result in a crisis for the company.

3. Research Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Tactical Indicators and the Value of a Customer

4.2. Customer Journey Mapping, Touchpoint Intensity, and the Value of a Customer

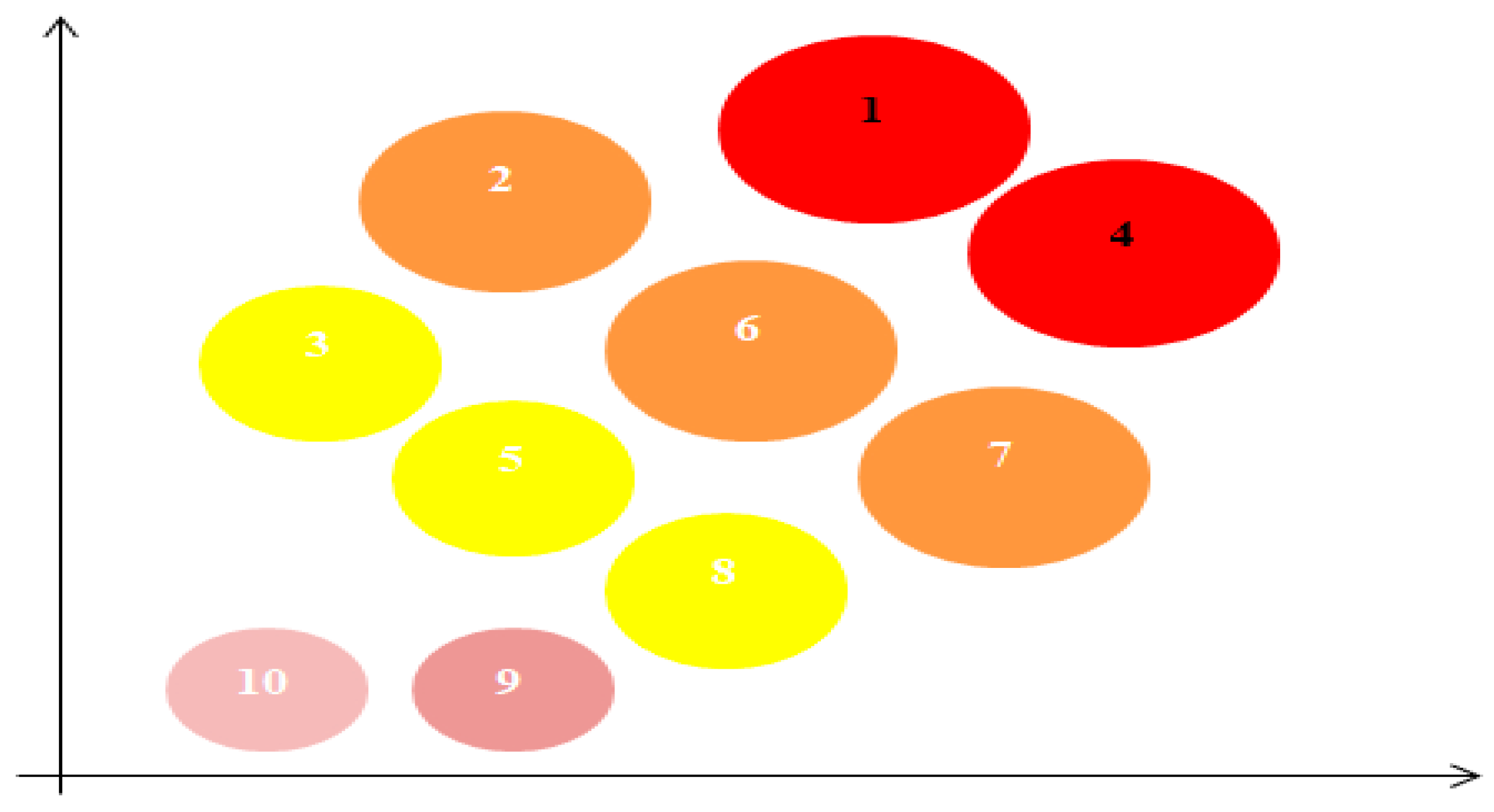

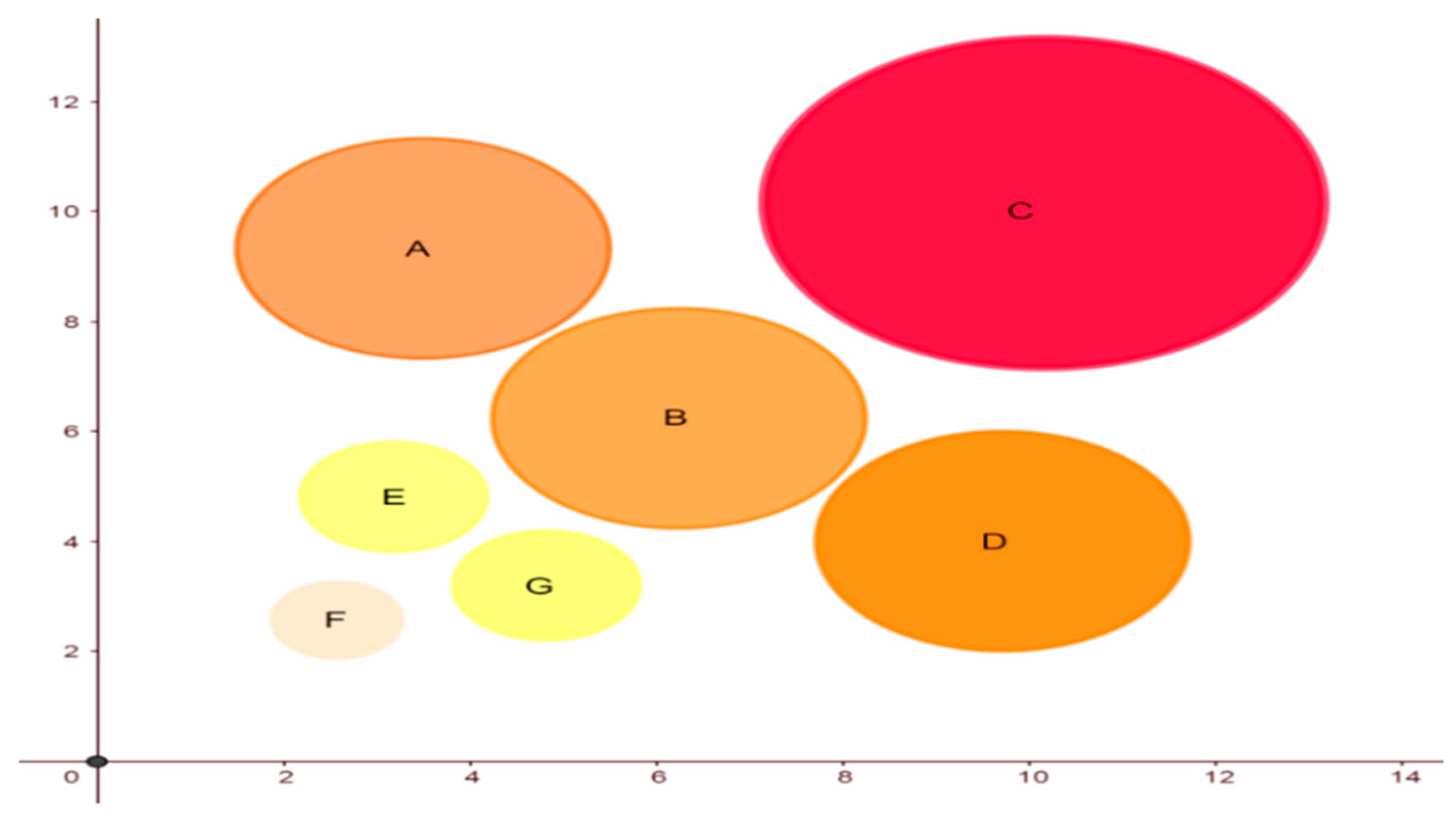

- Very positive customers (colored in red)—Comprising customers 1 and 4 as being the customers with highest shopping intensity, and positive customers (colored in orange)—Comprising customers 2, 6, and 7 with a lower shopping intensity.

- Neutral customers (colored in yellow)—Comprising customers 3, 5, and 8 with a reduced shopping intensity.

- Negative customers (colored in light pink)—Comprising customers 9 and 10, and it shows the lowest shopping value.

- Very positive touchpoints (colored in red)—Represent the intensity of the visits and shopping done in this department, and positive touchpoints (coloured in orange), which have lower intensity but are powerful enough.

- Neutral touchpoints (colored in yellow)—Show that the value obtained from customer shopping is reduced and ask for measures to improve the shopping level.

- Negative touchpoints (colored in light pink)—Show that the value of shopping done at this department is so low that important measures to improve it are needed.

4.3. Determining Customer Concentration and Mutual Dependency

4.4. Measuring the Correlation Between T, SW, and MD Using Spearman’s Test (r)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications for Employee-Customer Interaction

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alhumud, A.A.; Elshaer, I.A. Social Commerce and Customer-to-Customer Value Co-Creation Impact on Sustainable Customer Relationships. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.; Stough, R. Consumer Perceptions of AI Chatbots on Twitter (X) and Reddit: An Analysis of Social Media Sentiment and Interactive Marketing Strategies. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Ma, B.; Niu, Y. The Role of Creative Strategies in Enhancing Consumer Interaction with New Product Video Advertising. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Upadhyay, A.K. Value Co-Creation by Interactive AI in Fashion E-Commerce. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2440127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosasih, O.; Hidayat, K.; Hutahayan, B.; Sunarti. Achieving Sustainable Customer Loyalty in the Petrochemical Industry: The Effect of Service Innovation, Product Quality, and Corporate Image with Customer Satisfaction as a Mediator. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaqer, M.S.; Katar, I.M.; Abdelhadi, A. Investigating TQM Strategies for Sustainable Customer Satisfaction in GCC Telecommunications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.A. Sustainable Branding for B2B Industrial Companies: Impact on Customer Loyalty. Rev. Cicag 2025, 22, 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Le, X.C. Artificial Intelligence-Based Chatbots—A Motivation Underlying Sustainable Development in Banking: Standpoint of Customer Experience and Behavioral Outcomes. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2443570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragih, H.H.; Saifi, M.; Nuzula, N.F.; Worokinasih, S. Exploring the Nexus between Corporate Agility and Sustainable Strategy: The Role of Stakeholder Engagement and External Forces. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2438864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.J.; Huam, H.T.; Wong, S.Y.; Samson, J.; Fadzilah, A.H.H. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Customer Purchase Intention of Clothing Industry: An Integration of Triple Bottom Line and ISO26000. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2025, 14, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, M.C.G.; Arun, G. A Study on Environmental Prosocial Attitudes to Green Consumption Values, Openness to Green Communication, and Its Relationship with Buying Behavior. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2443050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, J. Can Artificial Intelligence Empower Energy Enterprises to Cope with Climate Policy Uncertainty? Energy Econ. 2025, 141, 108088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsree, K.; Naruetharadhol, P. Unveiling the Determinants of Alternative Payment Adoption: Exploring the Factors Shaping Generation Z’s Intentions in Thailand. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratas, J.M.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Carvalho, M.A. Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) for Retail and Service Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wadman, W.M. Variable Quality in Consumer Theory; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kavita, C.; Gowrisankar, A.; Serpa, C. Analyzing Crude Oil Price Fluctuations: A Fractal Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Nonlinear Dynamics and Applications (ICNDA 20024), Volume 2, Majitar, India, 21–23 February 2024; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Jain, V.; Ambika, A. Designing an Empathetic User-Centric Customer Support Organisation: Practitioners’ Perspectives. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 58, 845–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.; Machado, J.; Sampaio, P. Predictive Quality Model for Customer Defects. TQM J. 2024, 36, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, K.; Misra, S. Analysis of Customer Reviews with an Improved VADER Lexicon Classifier. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, U.B.; Alniacik, U. Interactive Effects of Market Orientation, Innovation Orientation and Sales Control Systems on Firm Performance in B2B Markets. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.C.; Lee, Y.Y. Explaining the Gift-Giving Intentions of Live-Streaming Audiences through Social Presence: The Perspective of Interactive Marketing. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 945–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.; Gandhi, A. The Branding Power of Social Media Influencers: An Interactive Marketing Approach. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2380807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Xue, S.; Wang, T. The Influence of Repeated Two-Syllable Communication Strategy on AI Customer Service Interaction. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, R. Resource-Advantage Theory, Resource-Based Theory and Market-Based Resources Advantage: Effect of Marketing Performance on Customer Information Assets Stock and Information Analysis Capabilities. J. Mark. Manag. 2024, 40, 1135–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, J. Influencer-Product Attractiveness Transference in Interactive Fashion Marketing: The Moderated Moderating Effect of Speciesism Against AI. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Hao, Y.; Xie, L. Virtual Influencers and Corporate Reputation: From Marketing Game to Empirical Analysis. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 759–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.C. Integrating or Tailoring? Optimizing Touchpoints for Enhanced Omnichannel Customer Experience. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, E.L.; Dahl, A.; Peltier, J.W. Health-Care Marketing in an Omni-Channel Environment: Exploring Telemedicine and Other Digital Touchpoints. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2019, 13, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straker, K.; Wrigley, C.; Rosemann, M. Typologies and Touchpoints: Designing Multi-Channel Digital Strategies. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ma, X.; Fei, W.; Jiang, Q.; Qin, W. Is More Always Better? Investor-Firm Interactions, Market Competition and Innovation Performance of Firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 210, 123856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambra-Fierro, J.; Patricio, L.; Polo-Redondo, Y.; Trifu, A. It’s the Moment of Truth: A Longitudinal Study of Touchpoint Influence on Business-to-Business Relationships. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapresta-Romero, S.; Becker, L.; Hernandez-Ortega, B.; Terho, H.; Franco, J.L. Getting the Recipe Right: How Content Combinations Drive Social Media Engagement Behaviors. J. Interact. Mark. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Chung, K.-w.; Nam, K.-Y. Orchestrating Designable Touchpoints for Service Businesses. Des. Manag. Rev. 2013, 23, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidig, J.; Weippert, M.; Kuehnl, C. Personalized Touchpoints and Customer Experience: A Conceptual Synthesis. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 177, 114641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Zuo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Kaneko, Y. Application of Fractal Analysis for Customer Classification Based on Path Data. In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops ICDMW, Auckland, New Zealand, 7–10 December 2021; Volume 2021, pp. 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, Y. Fractal Analysis of a Grocery Store Shopping Path. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd Asia-Pacific World Congress on Computer Science and Engineering (APWC ON CSE 2015), Nadi, Fiji, 2–4 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dawi, N.B.M.; Gupta, N.; Namazi, H. The Application of Fractal Theory in Marketing: What Can We Do? Fractals 2025, 33, 2530006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Gomez, L.E.; Cano, V.; Garcia, S.; Espinoza, A. Fractal modeling for rational consumer. Rev. ECORFAN 2011, 2, 190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, O.; Oh, G. Multifractal Analysis of Consumer Behavior During COVID-19. In Fractal-Complex Geometry Patterns and Scaling in Nature and Society; World Scientific: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.L. The complexity and recognizable information business trademarks design—Applied fractal analysis and fractal dimension. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Materials for Science and Engineering (IEEE-ICAMSE 2016), Tainan, Taiwan, 12–13 November 2016; pp. 408–411. [Google Scholar]

- Manglik, R. Analysis & Design of Information Systems; EduGorilla Publication: Lucknow, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, A.; Khare, A.; Mack, O.; Burgartz, T. Managing in a VUCA World; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lantada, A.D. Handbook on Advanced Design and Manufacturing Technologies for Biomedical Devices; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Calow, P.P. Encyclopedia of Ecology and Environmental Management; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding Customer Experience Throughout the Customer Journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machala, J. Marketing Metrics in Customer Experience Management. In VISION 2025: Education Excellence and Management of Innovations through Sustainable Economic Competitive Advantage; Soliman, K.S., Ed.; International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA): Norristown, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 11870–11874. [Google Scholar]

- Gahler, M.; Klein, J.F.; Paul, M. Customer Experience: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Application in Omnichannel Environments. J. Serv. Res. 2023, 26, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.; Carlson, J.; Gudergan, S.P.; Wetzels, M.; Grewal, D. How Do Omnichannel Customer Experiences Affect Customer Engagement? Theory and Empirical Validation. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 189, 115196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, F.O.; Lim, W.M.; Sampaio, C.H.; Rasul, T.; Ladeira, W.J.; Thaichon, P.; Choudhury, D. The Robot-Human Paradox: A Meta-Analysis of Customer Service by Robots versus Humans on Customer Experience. J. Consum. Behav. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.F.; Shamim, A.; Thaichon, P.; Quach, S.; Siddique, J.; Awan, M.I. Holistic Customer Experience: Interplay Between Retail Experience Quality, Customer In-Shop Emotion Valence and In-Shop Involvement Valence. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.S.; Otalora, M.L.; Ramirez, G.C. How to Create a Realistic Customer Journey Map. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrave, J. The Journey Mapping Playbook: A Practical Guide to Preparing, Facilitating and Unlocking the Value of Customer Journey Mapping; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mele, C.; Di Bernardo, I.; Ranieri, A.; Spena, T.R. Phygital Customer Journey: A Practice-Based Approach. Qual. Mark. Res. 2024, 27, 388–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herhausen, D.; Kleinrecher, K.; Verhoef, P.C.; Emrich, O.; Rudolph, T. Loyalty Formation for Different Customer Journey Segments. J. Retail. 2019, 95, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Goncalves, H.M. Consumer Decision Journey: Mapping with Real-Time Longitudinal Online and Offline Touchpoint Data. Eur. Manag. J. 2024, 42, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.L.; Araujo, M.D.R.; Reis, L.P.; Santos, J.P.M. Marketing and Smart Technologies: Proceedings of ICMarkTech 2022; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abbing, E.R. Brand-Driven Innovation: Strategies for Development and Design; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R.W. Qualitative Consumer Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzbühler, A.-M.; Kleijnen, M.H.P.; Verlegh, P.W.J. Outsourcing the Pain, Keeping the Pleasure: Effects of Outsourced Touchpoints in the Customer Journey. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Yang, M.; Wen, J. The M/M/1 Repairable Queueing System with Two Types of Server Breakdowns and Negative Customers. Eng. Lett. 2024, 32, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zahari, A.R.; Esa, E.; Asshidin, N.H.N.; Surbaini, K.N.; Abdullah, A.E. Mobile Touchpoint and Customer Effort: A Case of a Leading Energy Firm in Malaysia. Environ.-Behav. Proc. J. 2023, 8, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Reinartz, W. Customer Relationship Management: Concept, Strategy, and Tools; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ghose, A. Tap: Unlocking the Mobile Economy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, L. Lean AI: How Innovative Startups Use Artificial Intelligence to Grow; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial—What Is an Interactive Marketing Perspective and What Are Emerging Research Areas? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.; Wasley, C.E.; Zach, T. Information Externalities along the Supply Chain: The Economic Determinants of Suppliers’ Stock Price Reaction to Their Customers’ Earnings Announcements. Contemp. Account. Res. 2011, 28, 1304–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vrande, V. Balancing Your Technology-Sourcing Portfolio: How Sourcing Mode Diversity Enhances Innovative Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artun, O.; Levin, D. Predictive Marketing: Easy Ways Every Marketer Can Use Customer Analytics and Big Data; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, R.; Kelleher, B. Customer Experience for Dummies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vo, D.T.; Nguyen, L.T.V.; Dang-Pham, D.; Hoang, A.P. When Young Customers Co-Create Value of AI-Powered Branded App: The Mediating Role of Perceived Authenticity. Young Consum. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; D’Souza, C. Pre-Cycling Contemplation—An Explanation on the Interplay between Recycling Consideration and Purchase Intention, and the Role of Semiotic Knowledge. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2370907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Li, Y. Customer Journey Design in Omnichannel Retailing: Examining the Effect of Autonomy-Competence-Relatedness in Brand Relationship Building. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Hudson, L. Customer Service in Tourism and Hospitality; Goodfellow Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Klopper, H.B.; Berndt, A.; Chipp, K.; Ismail, Z.; Lombard-Roberts, M. Fresh Perspectives: Marketing; Pearson South Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinatenkamp, M. Relationship Theory and Business Markets; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hanika, M.; Gatzert, N. Survey-Based Insights from Choice-Based Conjoint Analyses on Customer Preferences for Company Characteristics of Life Insurers. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2024, 27, 451–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, L.; Kindström, D. Managing Digitalized Touchpoints in B2B Customer Journeys. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 121, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.T.; Nguyen, L.V.T.; Dang-Pham, D.; Hoang, A.P. What Makes an App Authentic? Determining Antecedents of Perceived Authenticity in an AI-Powered Service App. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 163, 108495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PhamThi, H.; Ho, T.N. Understanding Customer Experience over Time and Customer Citizenship Behavior in Retail Environment: The Mediating Role of Customer Brand Relationship Strength. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 11, 2292487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, A.; Bigné, E.; Navas, L.F.R. Consumer Brand Choice in the Metaverse: Exploring Personal and Social Factors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2025, 213, 124033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathali, M.; Heidarzadeh, H.K.; Khounsiavash, M.; Zaboli, R. Development and Validation of Omni-Channel Shopping Value Scale in Iran. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2025, 34, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folse, J.A.G.; Bock, D.E.; Mangus, S.M.; Hall, K.K.L. Online Chat Encounters: Satisfying Customers through Dialogical Interaction. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 190, 115197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. New Frontiers and Future Directions in Interactive Marketing: Inaugural Editorial. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Prasad, A.; Ratchford, B.T. Consumer Spending Patterns across Firms and Categories: Application to the Size- and Share-of-Wallet. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2016, 33, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.R.; Losada, M.O.; Pena-Garcia, N.; Dakduk, S.; Lourenco, C.E. Do Peer-to-Peer Interaction and Peace of Mind Matter to the Generation Z Customer Experience? A Moderation-Mediation Analysis of Retail Experiences. J. Mark. Anal. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chen, Y. Invisible to Influential: Customer Emotional Labour’s Impact on Luxury Services. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhamtani, A.; Mehta, R.; Singh, S. Size of Wallet Estimation: Application of K-Nearest Neighbour and Quantile Regression. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2021, 33, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osakwe, C.N. Effects of Customer Characteristics and Service Quality on Share of Wallet in Neighborhood Shops Based on an Asymmetric Approach. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022, 34, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, X.; Chan, K.C. Does Customer Concentration Disclosure Affect IPO Pricing? Financ. Res. Lett. 2019, 28, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, W. Corporate Customer Concentration and Stock Price Crash Risk. J. Bank. Financ. 2020, 119, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H. The Effects of Major Customer Networks on Supplier Profitability. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Ma, D.; Sun, L. Customer Concentration and Corporate Risk-Taking. J. Financ. Stab. 2021, 54, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboo, A.R.; Kumar, V.; Anand, A. Assessing the Impact of Customer Concentration on Initial Public Offering and Balance Sheet-Based Outcomes. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Yu, M.; Liu, J.; Fan, R. Customer Concentration and Corporate Innovation: Evidence from China. North Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2020, 54, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J.G.; Graham, C.; Trinh, G. The Long-Term Erosion of Repeat-Purchase Loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 763–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Xia, N.; Zhang, J. Customer-Based Concentration and Firm Innovation. Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2018, 47, 248–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciaro, T.; Piskorski, M.J. Power Imbalance, Mutual Dependence, and Constraint Absorption: A Closer Look at Resource Dependence Theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 167–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, T.G.; Lisboa, I.; Teixeira, N.M. Handbook of Research on Reinventing Economies and Organizations Following a Global Health Crisis; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoi, K.S. Principles of Test Theories; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Chai, X. Social Interactions in Queueing Systems: Pricing Decision with Reference Time Effect. Methodol. Comput. Appl. Probab. 2025, 27, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, V.; Cuc, D.L.; Rad, D.; Wysocki, D.; Pantea, M.F.; Batca Dumitru, G.C. How “Accountant” Are You on the Bean Counter Scale? A Validation Study. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2024, 23, 44–65. [Google Scholar]

| Customer/Dep | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | SW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 37.69 | 37.99 | 18.28 | 12 | 0 | 15 | 150.96 |

| 2 | 94.46 | 35.58 | 54.63 | 43.4 | 181.87 | 0 | 0 | 409.94 |

| 3 | 37.6 | 64.5 | 134.21 | 79.58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 315.89 |

| 4 | 23.98 | 46.7 | 45.61 | 105 | 104.28 | 0 | 26 | 351.57 |

| 5 | 127.59 | 50.3 | 85.58 | 25.64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 289.11 |

| 6 | 47.25 | 78.46 | 227.4 | 31.04 | 0 | 0 | 53.4 | 437.55 |

| 7 | 13.62 | 24.98 | 79.17 | 33.14 | 196.36 | 0 | 0 | 347.27 |

| 8 | 77.41 | 36.26 | 52.23 | 35.19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 201.09 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 240 | 0 | 0 | 200 | 236 | 676 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 175 | 0 | 175 |

| Total | 451.91 | 374.47 | 956.82 | 371.27 | 494.51 | 375 | 330.4 | 3354.38 |

| Customer/Dep | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOW | SOW | SOW | SOW | SOW | SOW | SOW | |

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.1 |

| 2 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.44 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0.12 | 0.2 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.07 |

| 5 | 0.44 | 0.17 | 0.3 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 |

| 7 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.1 | 0.57 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0.36 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.35 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Customer/Dep | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCR | SCR | SCR | SCR | SCR | SCR | SCR | |

| 1 | 0.066 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.05 |

| 2 | 0.028 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0.011 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0.007 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0 | 0.08 |

| 5 | 0.038 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0.014 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0.16 |

| 7 | 0.004 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0.023 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0.53 | 0.71 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.47 | 0 |

| Customer | The Route Colour | Touchpoints (Departments) | No of Touchpoints |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | A, B, C, D, E, G | 6 |

| 2 | Yellow | A, B, C, D, E | 5 |

| 3 | Blue | A, B, C, D | 4 |

| 4 | Green | A, B, C, D, E, G | 6 |

| 5 | Orange | A, B, C, D | 4 |

| 6 | Grey | A, B, C, D, G | 5 |

| 7 | Mauve | A, B, C, D, E | 5 |

| 8 | Light green | A, B, C, D | 4 |

| 9 | Brown | C, F, G | 3 |

| 10 | Pink | G | 1 |

| Total | 43 |

| Cust | SW (1) | Place After SW | Sij (SWij/Tv) (2) | Cust. Ave. Wage (W) | Total Purch (TP) (90%W) (3) | Pji (SW/TP) (4) | Simetr Mutuality (Sij × Pji) (5) | wij (Sij/Sum of Sij) (6) | MD [wij × (Sij × Pij)] (7) | Place After MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 150.96 | 10 | 0.045 | 2500 | 2250 | 0.067 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.003 | 5 |

| 2 | 409.94 | 3 | 0.122 | 3000 | 2700 | 0.151 | 0.018 | 0.730 | 0.013 | 1 |

| 3 | 315.89 | 6 | 0.094 | 3500 | 3150 | 0.100 | 0.009 | 0.360 | 0.003 | 4 |

| 4 | 351.57 | 5 | 0.104 | 4000 | 3600 | 0.097 | 0.010 | 0.286 | 0.002 | 6 |

| 5 | 289.11 | 7 | 0.086 | 3500 | 3150 | 0.091 | 0.007 | 0.190 | 0.001 | 7 |

| 6 | 437.55 | 2 | 0.130 | 2500 | 2250 | 0.194 | 0.025 | 0.223 | 0.005 | 3 |

| 7 | 347.27 | 4 | 0.103 | 4000 | 3600 | 0.096 | 0.009 | 0.150 | 0.001 | 8 |

| 8 | 201.09 | 8 | 0.059 | 4500 | 4050 | 0.049 | 0.002 | 0.080 | 0.0002 | 9 |

| 9 | 676 | 1 | 0.201 | 4000 | 3600 | 0.187 | 0.037 | 0.212 | 0.008 | 2 |

| 10 | 175 | 9 | 0.052 | 3000 | 2700 | 0.064 | 0.003 | 0.052 | 0.0001 | 10 |

| Total (Tv) | 3354.38 | 1 |

| Customer | T | Place for SW | d1 = T-SW | Place for MD | d2 = T-MD | d3 = SW-MD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 10 | −4 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 25 |

| 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 16 | 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 4 | 6 | −2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| 4 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 7 | −3 | 9 | 7 | −3 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 4 | −1 | 1 |

| 7 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 8 | −3 | 9 | −4 | 16 |

| 8 | 4 | 8 | −4 | 16 | 9 | −5 | 25 | −1 | 1 |

| 9 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 1 | 9 | −8 | 64 | 10 | −9 | 81 | −1 | 1 |

| T | 128 | 146 | 53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Florea, N.-V.; Croitoru, G.; Duica, M.-C.; Ghibanu, I.-A.; Diaconeasa, A.-A. Using Fractal Thinking to Determine Consumer Patterns Necessary for Organizational Performance: An Approach Based on Touchpoint Pilot Modeling. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110732

Florea N-V, Croitoru G, Duica M-C, Ghibanu I-A, Diaconeasa A-A. Using Fractal Thinking to Determine Consumer Patterns Necessary for Organizational Performance: An Approach Based on Touchpoint Pilot Modeling. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(11):732. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110732

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlorea, Nicoleta-Valentina, Gabriel Croitoru, Mircea-Constantin Duica, Ionut-Adrian Ghibanu, and Aurelia-Aurora Diaconeasa. 2025. "Using Fractal Thinking to Determine Consumer Patterns Necessary for Organizational Performance: An Approach Based on Touchpoint Pilot Modeling" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 11: 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110732

APA StyleFlorea, N.-V., Croitoru, G., Duica, M.-C., Ghibanu, I.-A., & Diaconeasa, A.-A. (2025). Using Fractal Thinking to Determine Consumer Patterns Necessary for Organizational Performance: An Approach Based on Touchpoint Pilot Modeling. Fractal and Fractional, 9(11), 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110732