1. Introduction

The persistence and spread of viral diseases remain a major global concern. The wide distribution of viral pathogens means that virtually everyone is susceptible to at least one seasonal illness. Transmission commonly occurs through contact with infected individuals, air, or water, underlining the challenge of controlling outbreaks.

Mathematical modeling utilizing different methods [

1] plays a pivotal role in understanding and predicting the behavior of infectious diseases [

2]. In particular, in fractional calculus—comprising derivatives, piecewise differential operators and integrals of non-integer order—has emerged as a robust tool for modeling complex dynamical systems, such as epidemics, due to its capacity to capture memory effects and hereditary properties, factors overlooked by classical integer-order approaches [

3,

4,

5]. Among these, the Atangana–Baleanu (ABC) fractional derivative stands out for its non-singular and non-local kernel, offering enhanced accuracy and stability, particularly in biological and epidemiological models [

2]. Incorporating fuzzy logic into fractional differential modeling enables handling of uncertainties and imprecision within real-world epidemic data and parameters [

6]. Thus, integrating fuzzy logic with ABC fractional derivatives in the SEIQR model facilitates a comprehensive and robust framework capable of realistically capturing pandemic spread and informing control measures.

The history of influenza and related viral epidemics demonstrates the significant impact and evolving nature of such diseases. Notably, the 1918 flu pandemic marked a milestone, accompanied by recurring large-scale outbreaks over the past century. Diseases such as Swine Flu (H1N1) and COVID-19 exemplify the devastation caused by novel and re-emergent viral strains [

7]. These events highlight the urgency of developing reliable mathematical models to analyze and forecast epidemic trends.

Differential equations constitute the backbone of epidemic modeling, and contemporary approaches extend to multiple frameworks, including symmetry-based models, time-invariant parameters, and network-based structures [

8,

9]. Research devoted to the mathematical and computational study of epidemics continues to expand, particularly regarding new viral strains and the integration of advanced mathematical tools [

10]. For a comprehensive review of historical pandemics and their spread, see [

7].

To address the lack of models accounting for memory effects and uncertainties, previous works have considered diverse methodologies. These include the development of fractional epidemic models, innovations in numerical methods [

11], and the incorporation of fuzzy frameworks [

1,

3,

12,

13]. Recent studies have also employed stochastic modeling and machine learning techniques for analyzing and predicting epidemic dynamics [

14,

15].

Foundational insights into numerical analysis were provided in [

16]. Stability modifications in the SIR model were investigated in [

11,

17]. The mathematical theory of epidemics was initially presented in [

18], with further contributions from Allen [

19]. Machine learning techniques for COVID-19 classification based on amino acid encoding were employed in [

14]. The effectiveness of stability analysis and existence of solutions for a modified fractional SIRD COVID-19 model were studied in [

20].

Under lockdown conditions, the dynamics of COVID-19 in India were examined in [

21]. A discrete stochastic model for COVID-19 was provided in [

22], and the impact of diagnostic delays on transmission was addressed in [

23]. Stability investigation of fractional systems with the Riemann–Liouville derivative was supplied by Qian et al. in [

24]. Asymptotic carriers in dengue transmission dynamics with control interventions were detailed in [

25]. Forecasting of delayed SEIQ pandemic dynamics was explored in [

26]. Periodic boundary value problems for fractional differential equations with the Riemann–Liouville derivative were investigated in [

27]. Finally, both finite-time stability analysis and control of stochastic SIR epidemic models, particularly concerning COVID-19, were studied in [

15].

Fuzzy set theory, first introduced in 1965, addresses vagueness and ambiguity where crisp boundaries between states do not exist [

28]. By applying membership functions and fuzzy inference systems, fuzzy differential equations extend ordinary differential equations to incorporate imprecise or uncertain information, reflecting real-world complexities in epidemic data and modeling. The process of modeling with fuzzy logic involves formalizing membership functions, defining fuzzy rules, conducting fuzzification and defuzzification, discretizing relevant parameters, and choosing numerical solution methods tailored to the specific application.

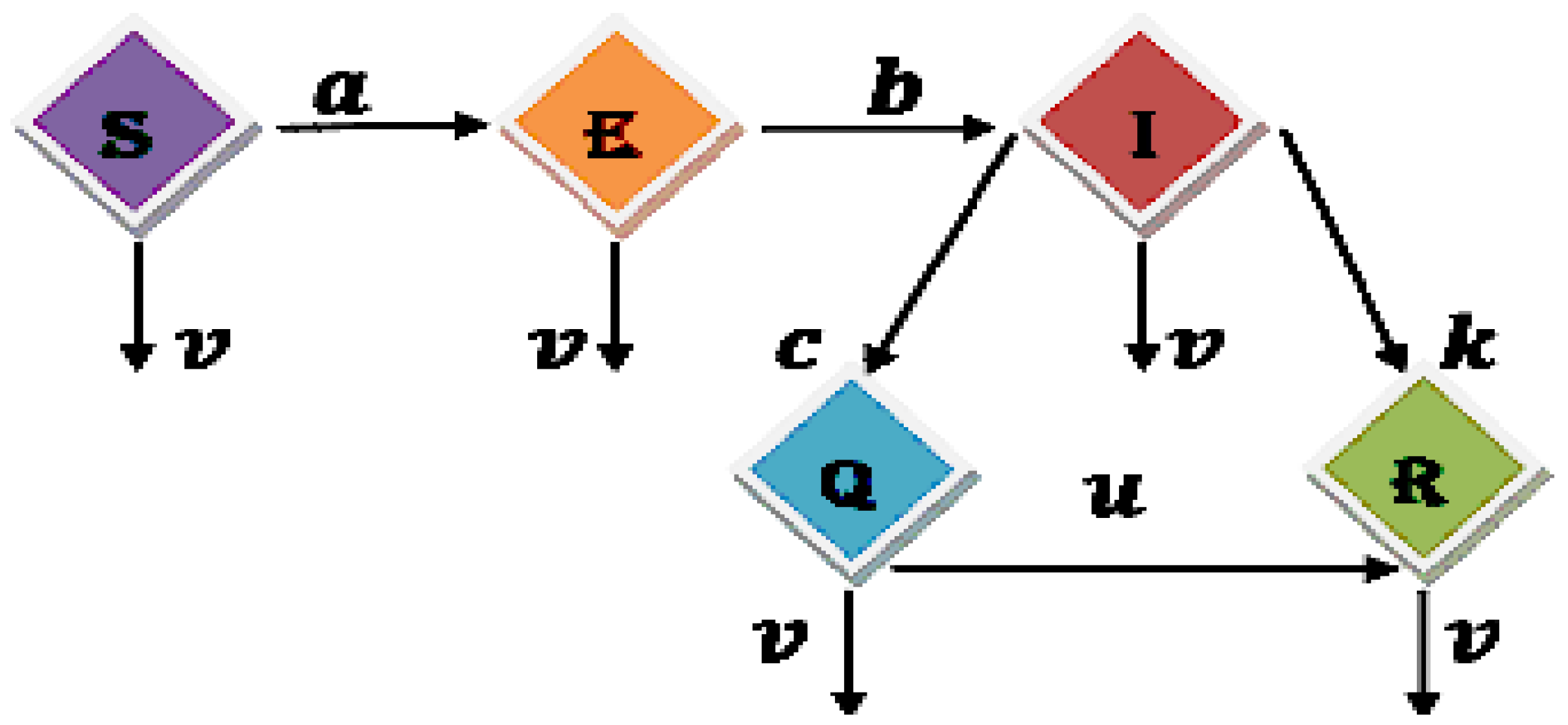

This study develops a novel fractional SEIQR epidemic model that uniquely integrates fuzzy logic with the Atangana–Baleanu-Caputo (ABC) derivative, an approach seldom explored in the context of pandemic modeling. The model makes explicit provision for mortality in all compartments, thereby enhancing its relevance for influenza-like diseases. Analytical investigations focus on stability and disease control thresholds amid fuzzy and fractional uncertainties, while efficient numerical simulation approaches are used to validate the theoretical findings and provide forecasts for epidemic trends and intervention effectiveness. Compared with conventional integer-order or crisp models, this approach underscores the potential of fuzzy fractional calculus in epidemiology.

The organization of the paper is as follows: In

Section 2,

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6, the work presents model formulation, essential background, analytical study, simulation results, conclusion, and discussion, respectively.

3. Preliminaries

For the benefit of readers, we highlight several important results on fractional differential equation (FDE) using the ABC derivative framework.

Definition 1 (Refs. [

6,

8,

9] Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo (ABC) fractional derivative).

Let and , and assume that is an absolutely continuous function. The ABC fractional derivative of order α is defined as follows:where Definition 2 (Refs. [

6,

8,

9] Laplace transform of the ABC fractional derivative).

Let denote the Laplace transform of f. For , the Laplace transform of the ABC fractional derivative defined in (2) is given byFurthermore, in the limit , one obtainswhich is the Laplace transform of the classical Caputo derivative. Definition 3 (Refs. [

6,

8,

9] Atangana–Baleanu fractional integral).

Let and let be any integrable function. The Atangana–Baleanu fractional integral of order α is defined bywhere is the same normalization function used in the ABC derivative, satisfying . As , one hasso the classical integral is recovered. We convert system (

1) to the following FDE, as shown in System (

5):

The fulfillment of initial conditions implies a constant net population size

N, given by

The population count of

are initially considered as

, and all of them equated to 100, i.e.,

.

In System (

5), the fractional orders are denoted as

, corresponding to the Susceptible (

S), Exposed (

E), Infected (

I), Quarantined (

Q), and Recovered (

R) compartments, respectively. This flexible multi-order framework allows for independent variation in each compartment’s fractional derivative order, enabling comprehensive analysis of heterogeneous memory effects across subpopulations.

While traditional studies often fix a single uniform order across all compartments, our approach facilitates richer dynamical exploration. For instance, the Susceptible dynamics can be examined at while simultaneously investigating Exposed behavior at or , and analogous flexibility applies to other compartments. Each governs the memory effects specific to its respective subpopulation, revealing compartment-specific fractional dynamics unattainable with uniform ordering.

This multi-fractional structure provides mathematical flexibility to study diverse epidemic scenarios, capturing varying hereditary influences on different disease stages and offering deeper insights into SEIQR model behavior compared to single-order formulations.

The parameter values of Susceptible-Exposed , Exposed-Infected , Infected-Quarantined , Infected-Recovered , Quarantined-Recovered , and Death used in all equations are, respectively, and

In epidemic modeling, fuzzy approaches are compelling for representing uncertainties inherent in parameters and population states. For instance, compartmental functions,

, are fuzzified into fuzzy-valued functions

,

using triangular fuzzy numbers with membership functions

defined piecewise as follows:

The initial population values are assumed to be equal across all compartments as a baseline to facilitate analysis of system stability while accommodating adjustment to real data as needed. Fractional calculus enhances model realism by incorporating memory effects and hereditary dynamics overlooked by classical integer-order differential equations. In this context, the ABC fractional derivative is employed due to its non-singular, non-local kernel, incorporating the Mittag–Leffler function and capturing biological memory in epidemic processes more accurately. Together, fuzzy logic and ABC fractional derivatives create a robust mathematical framework capable of modeling epidemic dynamics under uncertainty and memory influences.

Let

denote the fuzzy interval used to fuzzify the classical SEIQR model (

1). Applying this fuzzification to the ordinary epidemic model yields the fuzzy SEIQR system:

Building on this, the corresponding fuzzy fractional SEIQR system with ABC derivatives is

where

(or in the prescribed range) are the compartment-wise fractional orders.

The interval

thus defines a fuzzy scaling of any real-valued function

into a fuzzy-valued function:

so that each choice of

specifies one crisp representative within the fuzzy family

. It is important to note that the lower and upper bounds of each fuzzy function are defined as follows:

and therefore

Justification for Initial Conditions

The initial conditions for system (

5) are set as

(

), assuming a balanced distribution across all SEIQR compartments at

. This hypothetical baseline represents equal proportions in each compartment, providing an unbiased starting point for theoretical analysis of system dynamics.

This uniform initialization eliminates compartment-specific bias, enabling clear assessment of stability and long-term behavior without favoring any particular state. It facilitates controlled comparison between the classical integer-order model (

6) and the fuzzy fractional-order model (

7), isolating the effects of ABC fractional derivatives (

) and fuzzy uncertainty (

).

While real-world epidemics typically exhibit uneven distributions (e.g., high susceptible, low infected populations initially), this controlled setup is ideal for simulation studies. In practice, these values can be calibrated to empirical outbreak data using parameter estimation techniques. The baseline supports numerical simulations in

Section 5, where Laplace Adomian Decomposition Method (LADM) solutions demonstrate convergence to disease-free equilibrium across fractional orders, validating model robustness for realistic adjustments.

6. Results and Discussion

In this study, we developed and analyzed a fuzzy fractional-order SEIQR model to capture epidemic dynamics with both non-integer rate of changes and uncertainty. This classical framework served as the foundation for the fractional and fuzzy extensions presented in this work.

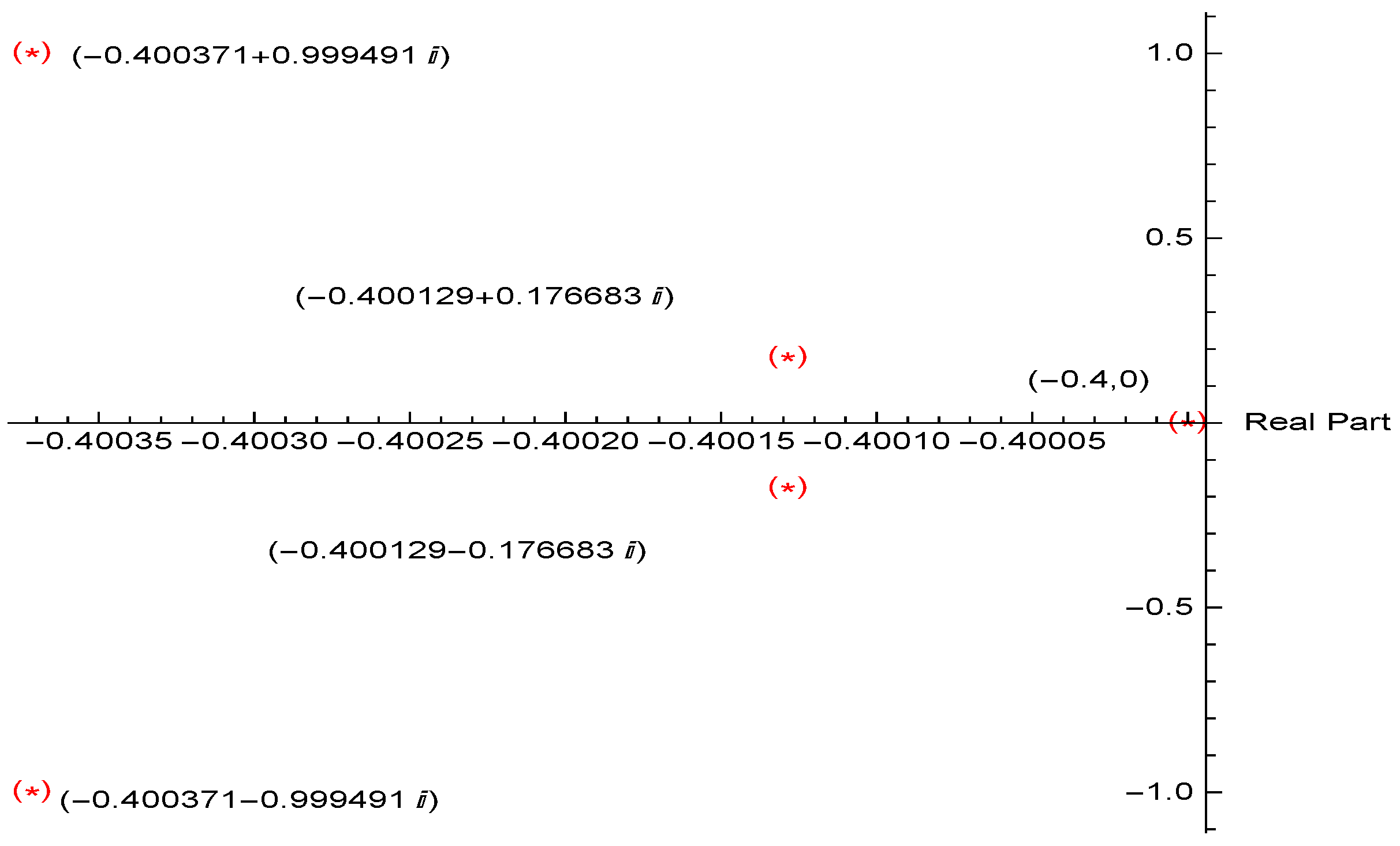

The stability properties of the system were investigated using eigenvalue analysis.

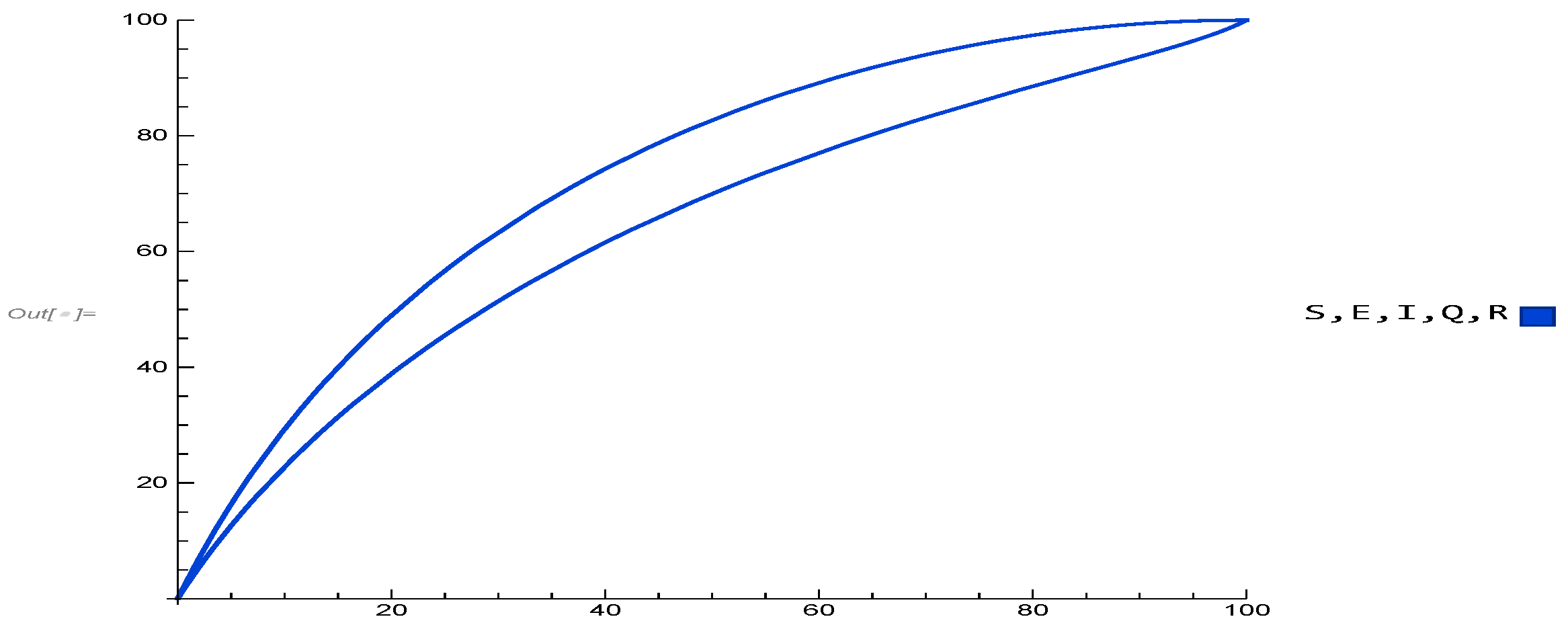

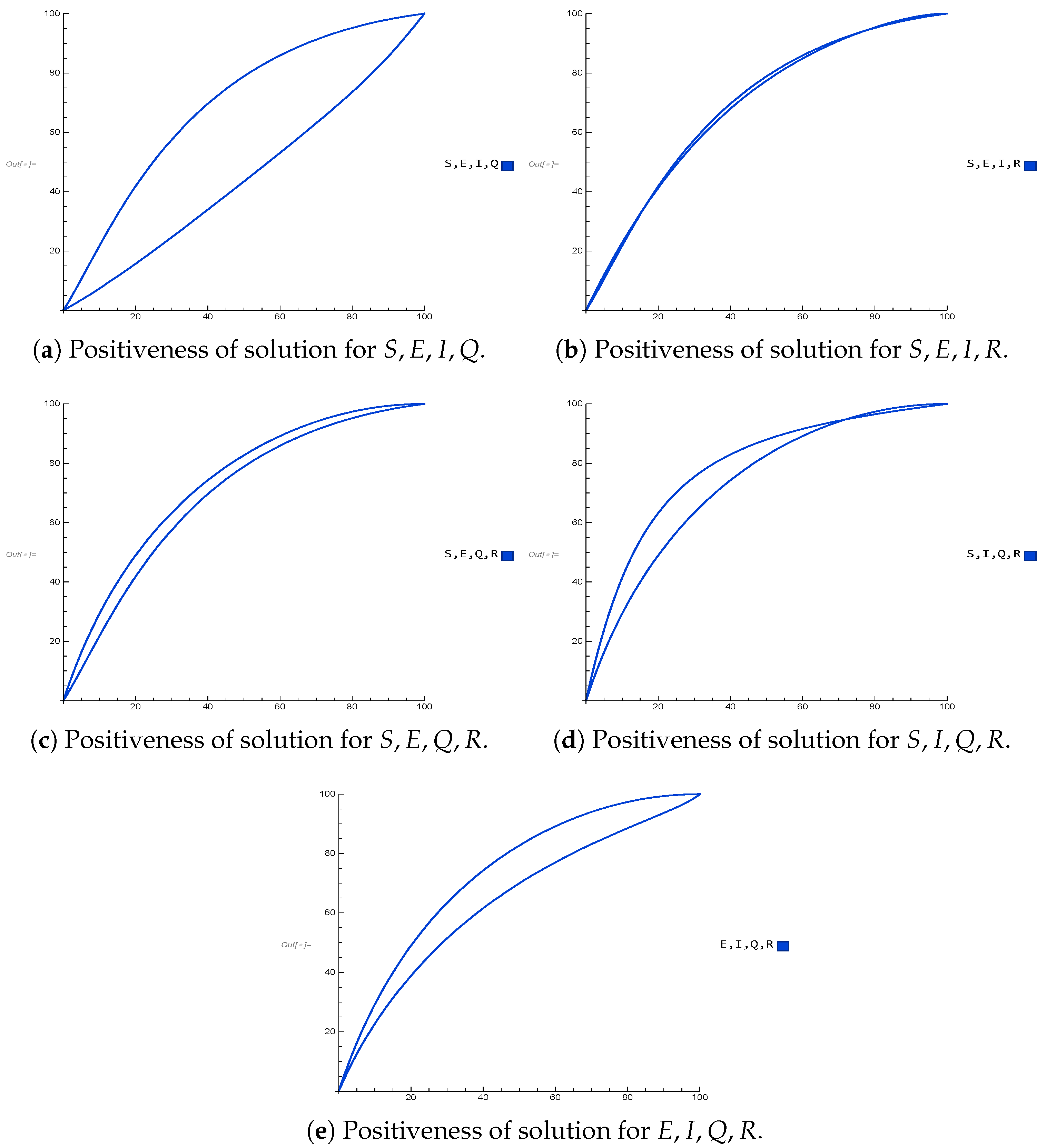

Figure 2 displays the real and imaginary parts of the eigenvalues, confirming the local asymptotic stability of the initial populations as in Remark 2 of Theorem 1, and in Theorem 1, the local asymptotic stability of IFE points is confirmed. This implies that, under appropriate parameter conditions, the infection will vanish over time. The biological validity of the model was also verified through positivity results (Theorem 2). As shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, all compartmental populations remain non-negative for both individual classes and their combinations, thereby ensuring feasibility of the framework.

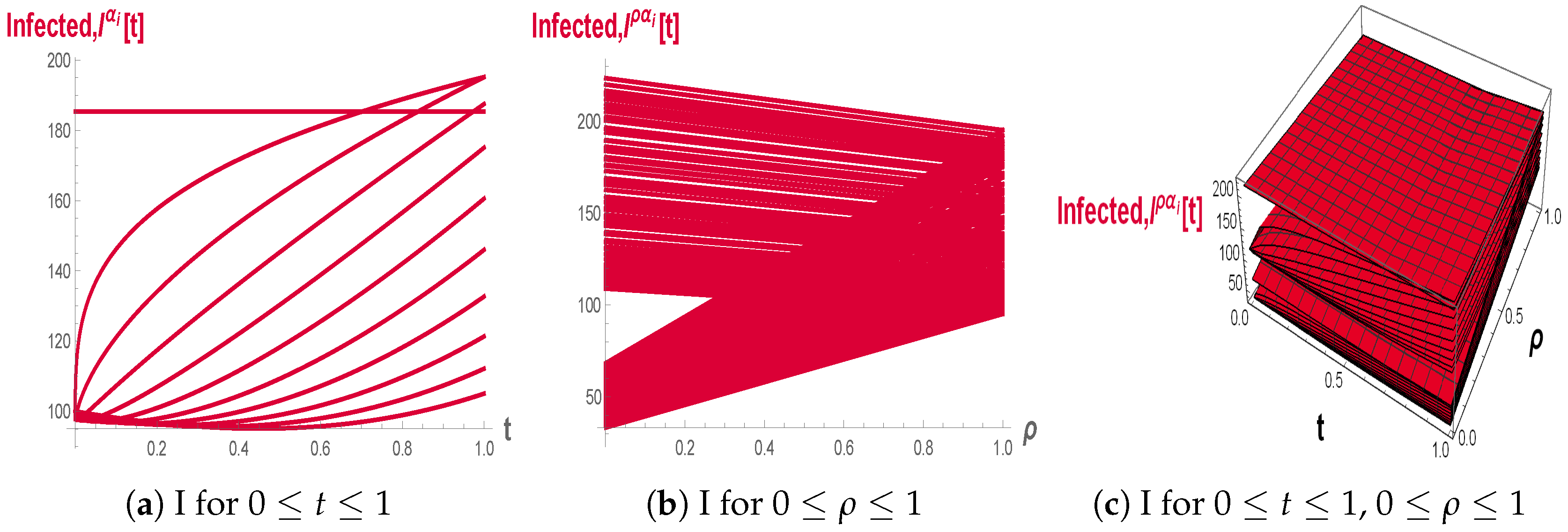

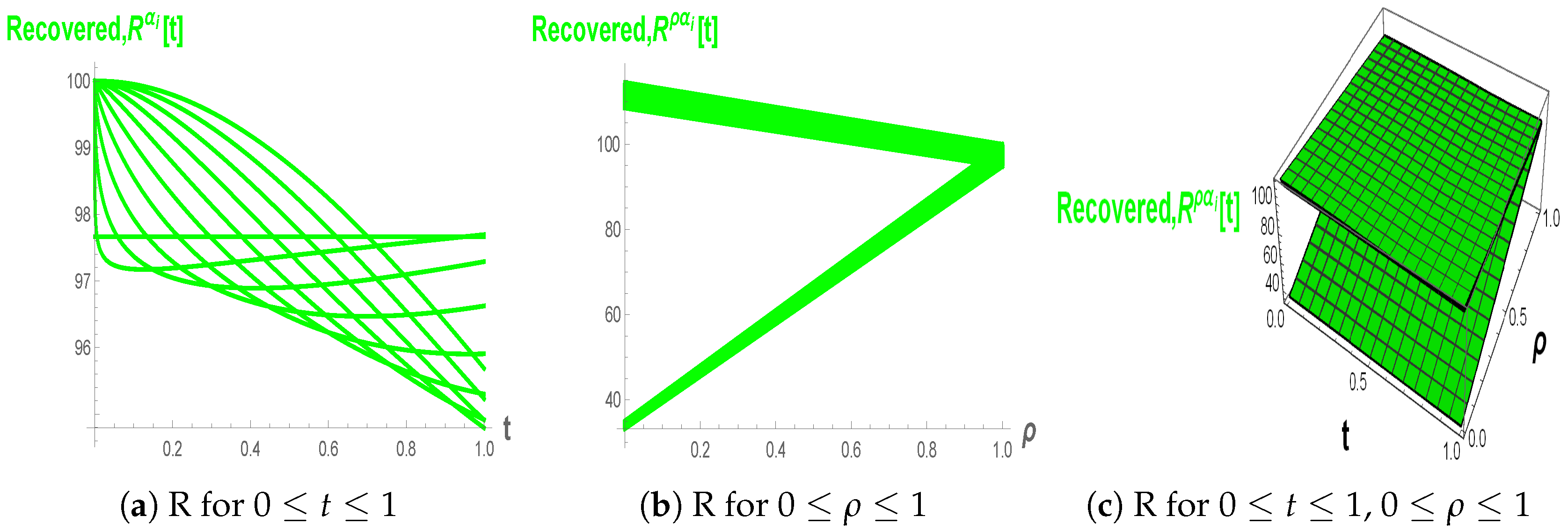

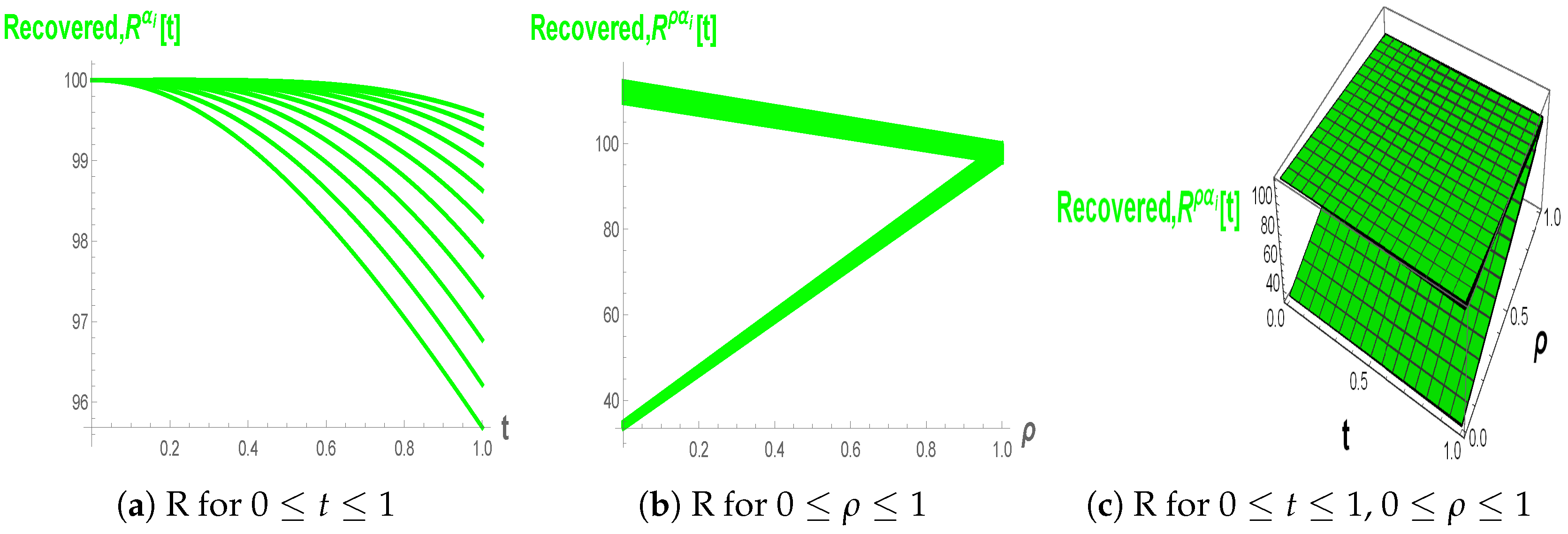

The fractional-order SEIQR epidemic model results are depicted in

Figure 6a–c,

Figure 7a–c,

Figure 8a–c,

Figure 9a–c,

Figure 10a–c,

Figure 11a–c,

Figure 12a–c,

Figure 13a–c,

Figure 14a–c and

Figure 15a–c. For each compartment (

), the figures labeled “a” show fractional-order dynamics over

and

, while those labeled “b” and “c” display fuzzy fractional cases two-dimensionally (2D) and three-dimensionally (3D) for both

and

, and

. The 2D plots are obtained by deriving the expression for both

or

and

and later varying these solutions for various

, whereas the 3D plots are carried out by deriving the expression for

or

and later varying these solutions for various

and

.

Unlike their integer-order counterparts, the fractional solutions exhibit slower decay of infections, reflecting memory effects and persistent epidemic activity. Increasing the fractional order (

), as in

Figure 11a–c,

Figure 12a–c,

Figure 13a–c,

Figure 14a–c and

Figure 15a–c, leads to quicker stabilization, demonstrating the flexible behavior enabled by fractional calculus.

The fuzzy fractional extensions, documented in

Figure 6b,

Figure 7b,

Figure 8b,

Figure 9b,

Figure 10b,

Figure 11b,

Figure 12b,

Figure 13b,

Figure 14b and

Figure 15b and

Figure 6c,

Figure 7c,

Figure 8c,

Figure 9c,

Figure 10c,

Figure 11c,

Figure 12c,

Figure 13c,

Figure 14c and

Figure 15c, capture parameter uncertainties. These figures show broad families of possible epidemic trajectories arising from variations in transmission and recovery rates. This integration of fuzziness yields a more comprehensive depiction of outcome ranges compared to deterministic models.

In particular, for

,

Figure 6a–c show that the Susceptible population

decreases monotonically over time, with smaller fractional orders producing a slower decay and hence a longer persistence of susceptibility in the population. The 2D and 3D fuzzy plots further indicate that as the fuzziness level

varies in

, the curves form a band of possible trajectories, reflecting uncertainty in the effective contact rate and illustrating a range of feasible epidemic paths for

.

Figure 7a–c illustrate that the Exposed population initially increases to a peak and then declines, and that lower values of

delay this peak and stretch the tail of

, evidencing the memory effect of the fractional operator. The fuzzy representations in panels (b) and (c) show how varying

generates a family of exposed trajectories, capturing uncertainty in progression from susceptibility to exposure.

In

Figure 8a–c, the Infected population exhibits a gradual rise followed by a slower decay when

, with smaller fractional orders leading to more persistent infection levels compared to higher orders. The fuzzy 2D and 3D plots demonstrate that changes in

widen the envelope of

trajectories, indicating that uncertainty in transmission and removal rates can substantially modify both the peak size and duration of the infectious phase.

Figure 9a–c show that the Quarantined population decreases over time for all fractional orders in

, with lower

again producing a slower decay, which can be interpreted as a longer retention of individuals in quarantine under stronger memory effects. The fuzzy plots reveal a sheet of plausible

curves over

, quantifying how parameter uncertainty influences the rate at which quarantine measures reduce the isolated population. As displayed in

Figure 10a–c, the Recovered population increases with time and approaches a plateau, and smaller fractional orders yield a more gradual growth, indicating that memory slows the accumulation of recovered individuals. The fuzzy fractional views in (b) and (c) show triangular–shaped bands in

–space, highlighting that uncertainty in recovery-related parameters generates a continuum of possible recovery curves around the nominal trajectory.

For

,

Figure 11a–c show that the Susceptible population

decays more rapidly than in the case

, indicating that higher fractional orders reduce the memory effect and drive the system closer to classical first–order dynamics. The fuzzy 2D and 3D plots in panels (b) and (c) reveal that, although variation of

still generates a band of admissible trajectories, the overall spread is narrower and the population stabilizes faster, reflecting reduced sensitivity to parameter uncertainty in this regime.

Figure 12a–c illustrate that, for

, the Exposed population

exhibits a shorter transient phase, with faster departure from the initial level and earlier decline compared to the lower–order case. The fuzzy surfaces show that increasing

compresses the range of possible exposed trajectories over

, suggesting that strong fractional effects attenuate the impact of uncertainty on the exposure dynamics. As seen in

Figure 13a–c, when

the Infected population

reaches lower peaks and returns more quickly towards baseline, demonstrating that higher fractional orders enhance the effective removal of infection. The fuzzy 2D and 3D plots indicate that the family of infected trajectories over

remains bounded within a relatively tight band, which means that in this parameter range the epidemic outcomes are less sensitive to moderate fluctuations in transmission and recovery rates.

Figure 14a–c show that the Quarantined population

decreases almost linearly in time for

, with little curvature compared to the sub-unitary orders, reflecting a more direct, non-memory-dominated decay of quarantined individuals. The fuzzy representations again form a relatively thin sheet over

, which indicates that, under higher fractional orders, the quarantine dynamics are comparatively robust to uncertainty in the underlying parameters. In

Figure 15a–c, the Recovered population

increases quickly and then saturates, and this saturation occurs earlier for

than in the case of

, highlighting the accelerating effect of higher fractional orders on the build-up of immunity. The fuzzy 2D and 3D plots reveal that, although uncertainty in

still generates a continuum of recovery curves, these trajectories cluster closely, showing that in the high-order regime, the long-term recovered level is only weakly affected by fuzziness in model parameters.

General model features such as formulation, equilibrium positivity, and stability supported by

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 confirm the robustness and utility of both fractional and fuzzy fractional SEIQR models.

From a computational perspective, the fourth-order LADM approach ensured the accuracy of fractional solutions. As

, the solutions of both classical and fractional models remain positive (Theorem 2), while increasing the LADM order reduces the decay rate and improves approximation precision. A summary of simulations across different parameter values is provided in

Table 1.

In conclusion, the classical SEIQR model offers a useful baseline, but fractional derivatives enrich the dynamics by incorporating fractional effects (), and fuzzy logic adds robustness by addressing uncertainty (). Together, these extensions provide a comprehensive and flexible framework for modeling epidemics. Beyond theoretical contributions, the model has practical applications in guiding vaccination strategies, quarantine measures, and adaptive policies to mitigate recurrent outbreaks. Future work will extend this framework to emerging variants, such as Omicron, further enhancing epidemic preparedness and management.

6.1. Key Findings

The investigation presents a fuzzy fractional SEIQR epidemic model, which can provide biologically meaningful solutions by the positivity, boundedness, and local asymptotic stability of the equilibrium if the parameters are chosen properly. The memory effects due to fractional-order dynamics can, depending on the order , either slow down or speed up the infection’s decay while the fuzzy extension parameterized by holds uncertainty in transmission and recovery, thus capturing not just one deterministic curve but families of plausible epidemic trajectories. The numerical experiments, which are based on the LADM scheme of the fourth order, not only verify the theoretical results but also showcase the model’s adaptability to represent various epidemic scenarios within one unified structure.

6.2. Limitations and Future Prospects

The current model presumes perfect mixing of the populations, constant parameters, and does not consider spatial heterogeneity, age structure, stochastic effects, or optimal control interventions. To add on, the parameter sets used in the simulations are merely illustrative and not fitted to the data; hence, direct quantitative prediction for specific diseases is out of the question. The next steps will be to fine-tune the fuzzy fractional SEIQR system to real epidemic datasets, make the parameters time-dependent or state-dependent, extend the structure to multi-region or network-based settings, and devise control or data-driven policies for vaccination, quarantine, and treatment under uncertainty that are optimum or driven by the data.