Abstract

The exponential growth of biomedical literature necessitates advanced methods for Literature-Based Discovery (LBD) to uncover hidden, meaningful relationships and generate novel hypotheses. This research integrates Large Language Models (LLMs), particularly transformer-based models, to enhance LBD processes. Leveraging LLMs’ capabilities in natural language understanding, information extraction, and hypothesis generation, we propose a framework that improves the scalability and precision of traditional LBD methods. Our approach integrates LLMs with semantic enhancement tools, continuous learning, domain-specific fine-tuning, and robust data cleansing processes, enabling automated analysis of vast text and identification of subtle patterns. Empirical validations, including scenarios on the effects of garlic on blood pressure and nutritional supplements on health outcomes, demonstrate the effectiveness of our LLM-based LBD framework in generating testable hypotheses. This research advances LBD methodologies, fosters interdisciplinary research, and accelerates discovery in the biomedical domain. Additionally, we discuss the potential of LLMs in drug discovery, highlighting their ability to extract and present key information from the literature. Detailed comparisons with traditional methods, including Swanson’s ABC model, highlight our approach’s advantages. This comprehensive approach opens new avenues for knowledge discovery and has the potential to revolutionize research practices. Future work will refine LLM techniques, explore Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), and expand the framework to other domains, with a focus on dehallucination.

1. Introduction

Literature-based discovery (LBD) has emerged as a significant area of research in the biomedical domain, aiming to uncover hidden relationships between disparate pieces of information in the scientific literature. The exponential growth of biomedical literature necessitates advanced computational approaches to assist researchers in identifying novel hypotheses and connections that may not be immediately apparent through traditional reading [1]. This article presents a novel framework that integrates LLMs into the LBD process, providing fresh insights into the application of LLMs in biomedical research. Our contribution is supported by empirical validations in biomedical literature scenarios, demonstrating the effectiveness of this new, rigorously tested framework.

Swanson’s ABC model underscores the potential to unearth hidden connections between disjointed literature sets [1], proposing that hidden insights (B) can link unrelated domains (A and C), leading to novel discoveries. Its impact is underscored by subsequent studies and methodologies that expand on its principles, employing advanced computational techniques, including AI and machine learning, to scale and automate the discovery process. This evolution highlights the model’s foundational role in the ongoing development of interdisciplinary research and its potential for generating novel insights. Swanson’s inspiring work on fish oil and Raynaud’s phenomenon marked the inception of LBD, demonstrating the possibility of linking disconnected literature to create new hypotheses. Subsequent developments have seen the integration of natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning techniques to automate and scale the discovery process [2].

Integrating generative AI, particularly LLMs like GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), into Swanson’s ABC model is a transformative approach to LBD. With their advanced capabilities in data processing, pattern recognition, and hypothesis generation, generative AI can significantly enhance the efficiency and depth of discovery within this model. As sophisticated generative models, LLMs are adept at parsing extensive textual information, identifying subtle patterns, and generating coherent, contextually relevant content, making them ideal for exploring and connecting complex datasets in LBD [3]. Their integration into Swanson’s ABC model will accelerate the identification of novel connections across vast literature and enrich the model with deep linguistic understanding and creativity, pushing the boundaries of interdisciplinary research and innovation.

Beyond their applications in the biomedical domain, LLMs have also demonstrated significant utility in educational and problem-solving contexts. For instance, Ref. [4] explored the use of LLMs as AI tutors in geotechnical engineering education, showing how they can enhance learning outcomes by efficiently providing targeted educational support. Similarly, Ref. [5] investigated the effectiveness of LLMs in geotechnical problem-solving, highlighting their ability to facilitate complex computations and enhance understanding in engineering scenarios. Advancements in pharma and biotech have broadened the scope of potential drug targets, including novel therapeutic modalities and unexplored genomic regions. LLMs are transforming drug discovery by efficiently extracting and presenting essential information from vast literature, aiding in identifying relevant target-disease relationships [6]. These studies underscore the versatility of LLMs in driving innovation across diverse fields, further supporting their integration into the LBD framework.

The primary motivation of this article is to address a few of the LBD challenges and to harness the capabilities of LLMs by playing a critical role in generating hypotheses and revealing hidden connections within the scientific literature. Traditional LBD methods, while foundational, often suffer from scalability issues, reliance on structured data, and manual curation, which limit their applicability in the modern research landscape. By integrating LLMs into the LBD workflow, we aim to expedite the research process significantly, enhancing the efficiency and depth of hypothesis generation and validation in the scientific community. Our LLM-based framework redefines the boundaries of traditional LBD by introducing continuous learning capabilities and domain-specific fine-tuning, providing a dynamic approach to hypothesis generation.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the current challenges in Literature-Based Discovery and the need to integrate advanced computational methods. Section 3 proposes the LLM-enabled LBD architecture. Section 4 details our proposed methodological framework, describing the integration of LLMs, semantic enhancements, and data-cleaning processes. Section 5 presents our empirical validations’ results, demonstrating our approach’s effectiveness in identifying hidden relationships in biomedical literature. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and points to some future research directions, including the potential for expanding the application of our framework to other domains and exploring additional technologies to enhance the discovery process further.

2. Related Work

This section presents a detailed view of LBD’s current state and historical development. Using Swanson’s ABC model, LBD has expanded dramatically by integrating advanced computational tools, semantic technologies, and interdisciplinary approaches. From the fundamental advancements in two-node search tools and semantic predications to the cutting-edge applications of generative AI models and LLMs, we trace the trajectory of LBD through its applications in diverse scientific fields such as healthcare, environmental science, and beyond. Additionally, we explore recent research initiatives highlighting LBD techniques’ ongoing expansion and adaptation, underscoring their significant role in driving scientific innovation.

- A

- Swanson’s ABC Model Evolution: Developments and Impact on Literature-Based DiscoverySwanson’s ABC model has undergone significant evolution since its inception. The model’s fundamental principle of linking disparate literature through shared concepts has been expanded upon by integrating advanced computational techniques and semantic resources. This evolution has profoundly impacted the field of literature-based discovery, enabling researchers to uncover hidden relationships and generate novel hypotheses with greater efficiency and accuracy. These developments have made the LBD process more efficient and scalable and expanded its potential to contribute to various fields, from healthcare to environmental science. They represent the continuing evolution of Swanson’s vision in the age of digital information, big data, and artificial intelligence. Some critical areas of this evolution are as follows:Two-Node Search Tools: Two-node search tools like Arrowsmith [7] are designed to identify biologically meaningful links between any two sets of articles in PubMed, even when they share no articles or authors in common. This approach allows users to explore indirect linkages between disparate topics or disciplines.Semantic Predications and Graph-Based Methods: Recent advancements in LBD involve the integration of semantic predications and graph-based methods. Semantic web technologies and ontologies (structured frameworks to represent knowledge in a specific domain) have enhanced the ability to semantically link different pieces of information and automate the discovery of potential A-B-C links. Tools like SemPathFinder [8] utilize graph embeddings and link prediction techniques to facilitate literature-based discovery in specific domains, such as Alzheimer’s Disease. By predicting potential connections between biomedical concepts, LitLinker [9] utilizes a graph-based approach to visualize and explore the relationships, facilitating the discovery of novel insights through LBD. Incorporating multi-level context terms into the ABC model, Lee et al.’s method [10] outperforms traditional techniques by delivering higher precision in uncovering meaningful drug-disease interactions from extensive biomedical texts. Their approach leverages a novel context vector-based analysis to discern more relevant and substantial connections within biological literature.Automated Knowledge Base Construction: Another approach in LBD is the automated construction of knowledge bases [11] from biomedical literature. This involves extracting entities and relations to represent information in different domains, such as nutrition, mental health, and natural product-drug interactions.Knowledge-Augmented NLP: The development of memory-augmented transformer models [12] that encode external biomedical knowledge into NLP systems shows promise in enhancing performance on knowledge-intensive tasks, such as LBD. Manjal [13] efficiently sifts through scientific publications from the MEDLINE database, extracting crucial information to streamline the research process and facilitate the discovery of novel insights. The study by Baek et al. [14] enhances hypothesis generation in biomedical research by integrating multiple biological terms and semantic relatedness into the ABC model, leveraging contextual information for more informed hypothesis development. These models leverage pre-existing domain knowledge to improve the identification and generation of hypotheses from biomedical texts.Integration with Databases and Big Data: LBD methodologies now often integrate with various scientific databases and utilize big data analytics. This integration allows for a more comprehensive and detailed exploration of potential links across a broader range of scientific knowledge. Agarwal and Searls [15] illustrate pharmaceutical research’s significant economic impact and enhancement through data-driven literature mining.Open and Closed Discovery Approaches: Open discovery involves generating a hypothesis by starting with a disease or concept and searching for substances or mechanisms related to it. Closed discovery focuses on evaluating and elaborating an initial hypothesis by searching for common mechanisms that link a disease with a substance or concept. The study [16] highlights the significant advancements in employing neural networks for LBD tasks. It demonstrates that these methods outperform traditional LBD techniques, underscoring the effectiveness and potential of incorporating neural network algorithms in discovering hidden relationships within biomedical literature. Drug Repurposing for COVID-19 via Knowledge Graph Completion [17] showcases a novel LBD approach combining semantic triples extracted using SemRep with neural knowledge graph completion algorithms, demonstrating the feasibility of neural network-based LBD in generating actionable medical hypotheses.Cross-Disciplinary Collaborations: There’s an increasing emphasis on cross-disciplinary collaborations, bringing together experts from different fields (e.g., biology, computer science, statistics) to enhance the discovery process. The study on cross-disciplinary research [18] offers an overview of the methodologies and findings related to cross-disciplinary research, utilizing bibliometric analyses to explore the collaboration between authors from different disciplines and the impact of such efforts.

- B

- Limitations of Traditional LBD Methods and the Need for Advanced FrameworksSwanson’s ABC model has been instrumental in uncovering hidden relationships between disparate pieces of information in the biomedical literature. However, it faces several challenges, particularly in terms of scalability, reliance on structured data, and the need for manual curation. These limitations have prompted the development of more advanced methodologies that leverage the capabilities of LLMs to enhance the LBD process.As illustrated in Table 1, our proposed LLM-based framework addresses these limitations by enhancing scalability, automating hypothesis generation, and enabling the integration of multimodal data sources.

Table 1. Comparison of limitations in traditional model with the proposed LLM-based framework.

Table 1. Comparison of limitations in traditional model with the proposed LLM-based framework. - C

- Recent advances in Literature-Based DiscoveryIn the field of literature-based discovery (LBD), building upon Dr. Swanson’s methodologies has focused on various innovative approaches and applications. The ongoing evolution of the LBD field is evident in its broadening applicability across different scientific domains, driven by advanced computational techniques such as LLMs. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of LLMs to uncover novel insights from biomedical literature, significantly enhancing the efficiency and depth of discovery processes [22]. The use of ChatGPT in LBD, as explored in recent studies, further showcases the advancements in LLM-based methods for literature discovery, particularly in biomedical research [23]. Comprehensive surveys have documented the broader impact of LLMs on drug discovery and development, underlining their growing influence in the healthcare domain [24,25]. Notable recent works include:

- Gap Analysis in Literature: A study by Peng et al. analyzed the concept of “gaps” [26] in literature as topics that should occur together but are unexpectedly missing. Their findings indicated that gap-filling articles on human diseases were often more cited and published in high-impact journals, underscoring LBD’s value as a knowledge discovery tool.

- Metabolomics and LBD: Henry et al.’s [20] work combined classic LBD techniques with high throughput metabolomic analyses. This study revealed new metabolomic pathways, identifying lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase as a potential target for cardiac arrest treatment. This represents a unique application of LBD in the field of metabolomics.

- Domain Independence and Visual Capabilities in LBD: Research by Mejia and Kajikawa [19] demonstrated that LBD could produce meaningful results in domains lacking controlled vocabularies, such as social sciences. Their approach utilized semantic similarity modeling and high-quality data visualizations to aid discovery.

- CHEMMESHNET: Introduced by Škrlj et al., CHEMMESHNET [21] is an extensive literature-based network of protein interactions derived from chemical MeSH keywords in PubMed. This network facilitates LBD tasks, particularly in discovering novel protein-protein interactions.

- Contextualized LBD: A recent study [27] focused on generating novel scientific directions using a contextualized approach to LBD. This involved using generation models like T5 and GPT3.5 for hypothesis generation and exploring dual-encoder models for node prediction, thereby advancing the scope of LBD in generating scientific hypotheses.

- BERT SPO Language Model in LBD: Another study employed the BERT SPO [28] language model to annotate SPO triples from the CORD-19 dataset for their importance, exploring a new way to identify significant information for LBD. This approach helped categorize data for more effective discovery and evaluation.

These approaches are integral to LBD, allowing researchers to explore new hypotheses and validate existing ones in a structured manner. - D

- Generative AI Models in Literature-Based DiscoveryGenerative AI models are revolutionizing LBD by automating the synthesis and analysis of vast scientific literature. These models facilitate the identification of novel insights and connections that may not be immediately apparent to human researchers, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery in various fields.Table 2 details critical insights from various state-of-the-art methods that explore the applications and impacts of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Generative AI across multiple disciplines, including healthcare, education, chemical research, and oncology. It highlights the essential findings and each study’s contribution to LBD.

Table 2. Generative AI and LLM applications on literature-based discovery.

Table 2. Generative AI and LLM applications on literature-based discovery. - E

- Current State of Large Language ModelsDespite their impressive capabilities, LLM’s are still under active development, with researchers tackling challenges such as factual accuracy and efficiency. Table 3 provides a snapshot of leading LLMs, highlighting their developers, release dates, training data size, and capabilities. Current LLMs vary significantly in size and training data, with models like PaLM boasting massive parameters, while others like ERNIE 3.0 prioritize efficiency with a smaller footprint. Despite these differences, most LLMs leverage techniques like fine-tuning and multi-tasking for increased adaptability and real-world application. Auto-regressive models, such as GPT-4 and LLaMA, build text step-by-step, predicting the next word based on the sequence before it. This approach offers a more controllable generation process but can be computationally expensive and prone to repetitive outputs. In contrast, non-autoregressive models, like PaLM, consider the entire context simultaneously to generate text. This can lead to more creative and diverse outputs but may also be less predictable and require additional post-processing for accuracy.

Table 3. State of the art on LLMs.

Table 3. State of the art on LLMs. - F

- LLM FeaturesLLMs offer numerous features that significantly enhance their utility in scientific research. Fine-tuning these models on domain-specific datasets enhances their understanding of scientific terminology, enabling more accurate and relevant responses in specialized fields. For instance, data from fine-tuning psychological experiments has demonstrated that LLMs can accurately model human behavior, even outperforming traditional cognitive models in decision-making domains [48]. Explainability is another crucial feature, where LLMs are integrated with techniques to elucidate their reasoning processes, providing clear explanations and supporting evidence for their outputs. The user interface plays a pivotal role, allowing researchers to input concepts and explore connections suggested by the LLM with detailed explanations and evidence, enhancing the research process [49]. Iterative refinement capabilities enable users to provide feedback, refining the model’s accuracy and relevance over time [50]. Continuous learning ensures that LLMs remain up-to-date by integrating new scientific publications and user feedback, continually improving their discovery capabilities [51]. These features collectively make LLMs indispensable tools for advancing scientific research and knowledge synthesis.

- G

- Limitations and Risks of LLMWhile LLM provides exciting features, as depicted above, it is worth highlighting some inherent challenges related to applying LLM, particularly the issue of hallucination. LLMs can generate responses containing information not present in the input, termed “hallucination”. This issue is pervasive across various models and applications, from vision-language models to text-based tasks [52]. Artificial hallucinations can undermine the reliability of LLMs in critical applications, such as medical and financial domains, and create risk and harm to a victim since accurate information is paramount [53]. LLMs often reflect biases in their training data, leading to unfair or discriminatory outputs [54]. LLMs struggle with multimodal tasks, such as those involving text and images, due to their inadequate integration of diverse data types [51]. They can also misunderstand the context or intent behind user queries, resulting in inappropriate responses. Furthermore, LLMs lack transparency in their decision-making processes, complicating their use in fields that demand explainability [55]. Lastly, their inability to retain information over time hinders the development of personalized responses unless specifically programmed for such tasks [56].

3. LLM Grounded Literature Discovery Model

Large Language Models and Generative AI perform complex data analysis and content creation by learning from extensive datasets to generate new, contextually relevant information and ideas. The general idea is that users pose open-ended questions or describe their area of interest using natural language, and the LLM, trained on a massive dataset of scientific publications, analyzes the user input and identifies relevant relationships within the literature. In this section, we present our proposed LBD model architecture that leverages Large Language Models to streamline the discovery of insights from vast research datasets.

LLM-Based Architecture

This section proposes an LLM-based architecture for literature discovery, and depicts the main components of this architecture and the interactions among them.

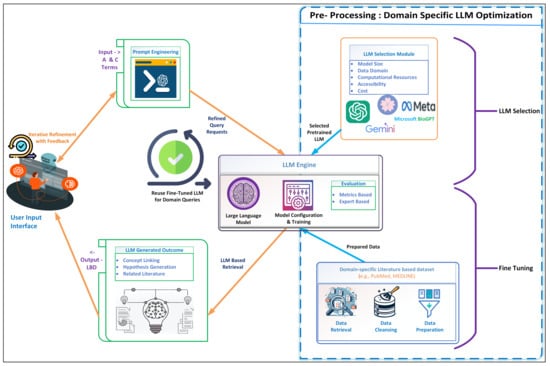

The architecture in Figure 1 illustrates the proposed LLM-based LBD system that implements an interactive and iterative process of knowledge extraction and hypothesis generation from the existing research landscape. At the front end, users interact with the system through a dedicated interface, providing input that is then refined through a sophisticated method of prompt engineering. This initial stage is critical as it ensures that the user’s input is optimally structured for subsequent processing by the LLM, thus underscoring the interactive nature of the system where the users refine their prompts based on iterative feedback. In this phase, input ’A’ and ’C’ terms are prompted and refined into a structured format. The refining process likely involves identifying the key concepts or terms from the inputs and rephrasing or structuring them into coherent prompts. For example, if ’A’ and ’C’ represent specific biomedical terms, prompt engineering would require the creation of refined query requests that instructs the LLM to search for literature discussing each term in isolation and how they might intersect or interact. This iterative process involves the system making suggestions or improvements, which are then refined based on the user’s feedback, symbolized by the looping arrow.

Figure 1.

LLM-based Architecture for Literature-Based Discovery.

Upon the engineering of prompts, the process transitions into a more sophisticated phase within the boundaries of the LLM. In this phase, the system is less transparent to the user, often called a ’black box’, wherein the blue lines represent complex and opaque interactions. The loop “Reuse Fine-Tuned LLM for Domain Queries” illustrates that the fine-tuned LLM can be reused across multiple queries within the same domain, rather than requiring retraining for each user input. This enhances efficiency and reduces computational costs.

Before user interaction, the LLM undergoes a rigorous selection process based on a multifaceted set of criteria, ensuring the chosen model aligns with the system’s scalability, domain specificity, and computational resource requirements. The LLM Selection Module evaluates models based on model size, data domain, computational resources, accessibility, and cost. The LLM selection and fine-tuning are conducted as a pre-processing step specific to the domain, ensuring that the selected LLM is optimally tuned before handling any user queries. We have segregated the “Pre-Processing: Domain Specific LLM Optimization” step in a dotted box to specify that this process is domain-specific and needs to be performed only once per domain.

Once selected, the LLM is subjected to a training procedure, referred to as fine-tuning, which means it is further trained on domain-specific datasets; for instance, in the case of biomedical literature-based discoveries, data sources such as PubMed or MEDLINE are used. Relevant data retrieval from the sources, cleansing, and preparation forms the backbone of the LLM’s operations, ensuring that the data used for fine-tuning the model is of the highest integrity, thereby directly influencing the quality of the LLM’s outputs. The LLM Engine clearly outlines the steps involved in preparing the LLM for use. This includes the LLM component, the model configuration and training process, and the evaluation phase. This fine-tuning process ensures the model’s outputs are highly relevant and accurate for the domain in question.

Finally, the output from the LLM is presented to the user. This output might include linked concepts, generated hypotheses, and related literature resulting from the user’s original query being processed through the literature-based discovery performed by the pre-trained LLM. To ensure transparency and explainability, these outputs are linked to specific PubMed IDs, allowing users to trace the model’s reasoning, explore connections between concepts, and validate findings. This provides a clear trail of evidence, enhancing the user’s understanding of relationships discovered from their query.

Throughout this process, the user’s interaction is mainly with the user interface, designed to be straightforward, without requiring the need to understand the complex processes happening within the LLM ’black box.’ The interface is built with usability in mind, incorporating intuitive design elements that allow users to easily input queries, refine prompts, and view results. A key feature of the interface is the display of hypotheses generated with linked literature, by displaying PMIDs or relevant source references alongside the generated results. This provides users with the ability to trace the LLM’s reasoning and validate the accuracy of the outputs. The interface also supports iterative refinement, where users can modify their queries based on feedback or results, enabling them to interactively refine the generated hypotheses and insights for deeper exploration of the literature connections.

Following training, the system’s architecture requires an evaluation process. This crucial step involves assessing the LLM’s performance through various metrics and expert analyses to validate its efficacy in generating relevant and accurate outputs. The model can be fine-tuned if required with feedback and relevant literature data.

After the LLM is fine-tuned and selected, the system is ready for continuous usage across multiple domain queries. The architecture ensures scalability, flexibility, and robust interaction between various components.

The LLM selection and fine-tuning process is not a one-time setup. The framework can be re-trained with new data, ensuring real-time adaptation to evolving scientific fields and maintaining relevance, unlike traditional static models.

4. Methodology

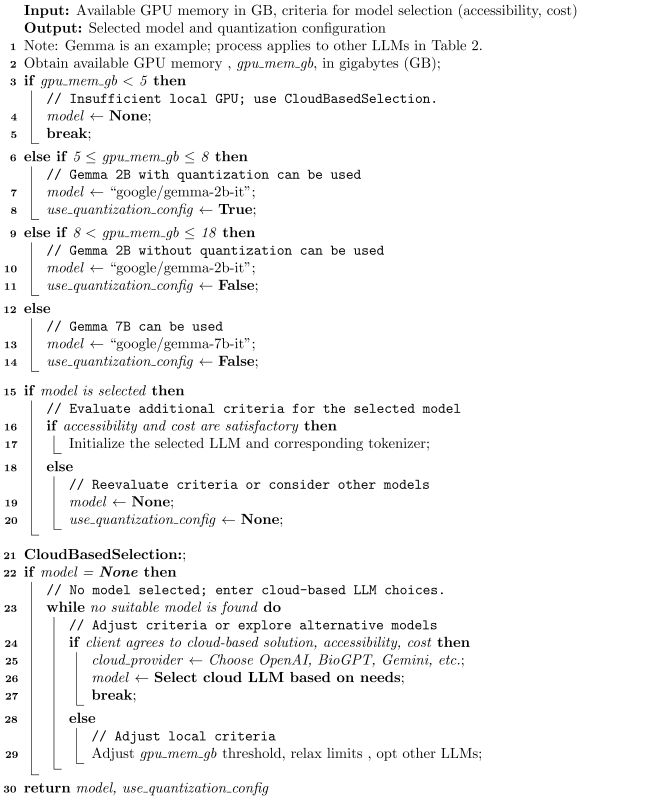

In this section, we present a comprehensive methodology comprising three key algorithms: Algorithm for LLM Model Selection, which ensures optimal model choice based on available GPU memory and additional criteria; Fine-Tuning (Data Preparation), which preprocesses domain-specific literature for ingestion by the LLM; and Hypothesis Generation, which leverages the preprocessed data and LLM capabilities to generate and validate meaningful hypotheses.

- A

- Algorithm for LLM Model SelectionWe developed Algorithm 1 to select an appropriate LLM based on the available GPU memory, ensuring optimal performance by matching the model to the hardware capabilities.The algorithm first checks the GPU memory and assigns the most suitable model, handling cases where there is insufficient memory by considering the use of quantized models or switching to cloud-based alternatives if necessary. Quantized models reduce the precision of the weights and activations (e.g., 32-bit to 8-bit) to decrease memory usage and improve inference speed, enabling deployment on hardware with limited resources [57]. If sufficient memory is available, the algorithm selects a complete model to leverage full precision and performance.When local resources are insufficient, the algorithm can switch to cloud-based LLMs, selecting from options such as OpenAI, BioGPT, or Gemini, based on criteria such as accessibility, cost, and model size. This comprehensive approach ensures that the selected LLM meets the specific needs of the task, whether through using local hardware, quantized models, or cloud-based resources, all while staying within the constraints of available resources.

- B

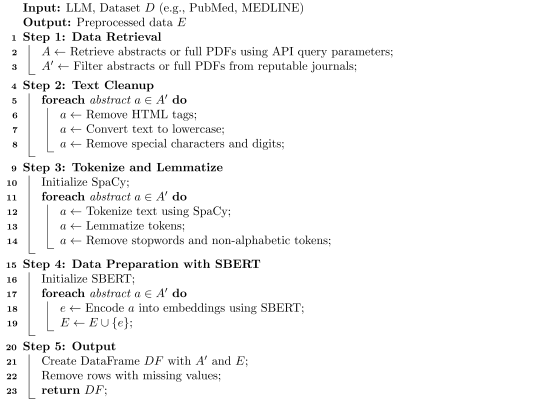

- Algorithm for Fine-TuningThe Fine-Tuning (Data Preparation) is detailed in Algorithm 2 and is designed to preprocess a domain-specific LBD dataset, such as abstracts or full PDFs retrieved from PubMed, to prepare the data for ingestion by a pre-trained LLM. The process begins with data retrieval, where relevant abstracts are fetched using the PubMed API based on specific query parameters. The abstracts are then filtered to include only those from reputable sources, such as Scopus-indexed journals, ensuring the quality and relevance of the dataset.Following data retrieval, the text is normalized and cleaned by removing HTML tags, converting it to lowercase and removing special characters and digits through regular expressions. This standardization ensures consistency across the dataset. In the next step, the text is tokenized and lemmatized. Tokenization involves breaking down the text into individual tokens (words or phrases), and lemmatization reduces words to their base or root form [58]. This step uses SpaCy [59] to tokenize the text, lemmatize tokens, and remove stopwords and non-alphabetic tokens, ensuring the text is in its most informative form for further processing.In the following step, text is encoded into sentence embeddings using SBERT (Sentence-BERT) [60], a variant of the BERT [46] model specifically designed to generate semantically meaningful embeddings for sentences. These embeddings capture the semantic content of the text in a multi-dimensional vector space, making them suitable for further processing and analysis by the LLM. Incorporating SBERT provides a substantial methodological improvement in the generation of sentence embeddings.Traditional BERT [46] architectures, while state-of-the-art in their performance on sentence-pair regression tasks are computationally intensive as they require pairwise sentence input, making them unsuitable for tasks like semantic similarity search across large datasets. SBERT modifies the pre-trained BERT [46] network to use Siamese [61] and triplet network structures, to derive semantically meaningful sentence embeddings that are efficient for comparison via cosine similarity [60].Finally, the cleaned abstracts and their corresponding embeddings are stored in a Data Frame, a data structure provided by the Pandas library for efficient data manipulation and analysis.Any rows with missing values are removed to ensure data completeness. The resulting cleaned and preprocessed data, now in the form of embeddings, is then outputted and ready for ingestion and utilization by the LLM for various downstream tasks, such as hypothesis generation. This comprehensive preprocessing pipeline ensures that the data fed into the LLM is high quality, relevant, and semantically rich.

- C

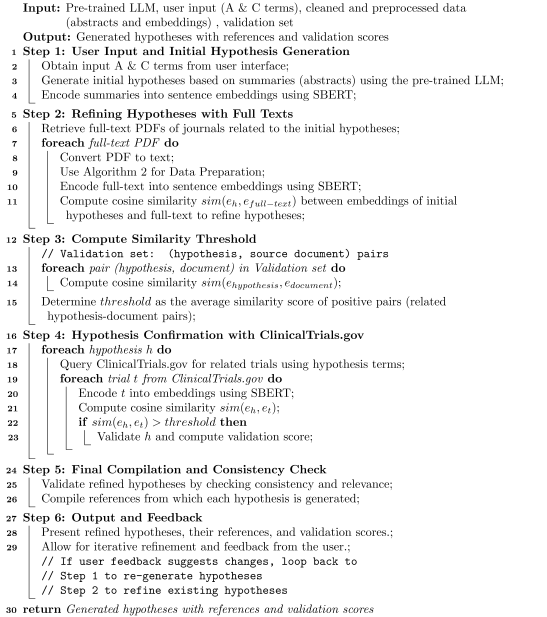

- Algorithm for Hypothesis GenerationThe hypothesis Generation is detailed in Algorithm 3 and inputs a pre-trained LLM and the cleaned, preprocessed data from the fine-tuning phase to generate meaningful hypotheses based on user inputs.The process begins by obtaining user input terms and generating initial hypotheses using LLMs, which are then encoded into sentence embeddings using SBERT. These embeddings are further refined by retrieving and analyzing full-text journal articles, ensuring that the hypotheses are well-supported by detailed and comprehensive sources. The cosine similarity between the embeddings of initial hypotheses and full-text documents helps in this refinement process.The algorithm computes a similarity threshold based on known related pairs from a validation set to validate the refined hypotheses. It then queries ClinicalTrials.gov [62] for related clinical trials and computes the cosine similarity between hypothesis and trial embeddings. Hypotheses with similarity scores exceeding the threshold are validated. The final step involves compiling references and presenting the validated hypotheses and their validation scores to the user. This user-centric approach ensures that the hypotheses are scientifically robust and practically relevant, allowing for iterative refinement based on user feedback.

| Algorithm 1: LLM Model Selection |

|

| Algorithm 2: Fine-tuning (Data Preparation) for LLM |

|

| Algorithm 3: Hypothesis Generation |

|

5. Experimental Evaluation

This section describes the experiments to evaluate our proposed LBD model, focusing on the dataset utilized, the experimental setup, the methodologies employed, and various scenarios tested to validate the system’s effectiveness in LBD.

5.1. Dataset

In our experiments, we have utilized the PubMed Medline database [63], maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), which serves as a crucial repository for citations and abstracts from life science journals. PubMed is accessed primarily through the Entrez search and retrieval system; PubMed offers an extensive range of data from a set of 34 databases containing 3.0 billion records. Entrez’s robust architecture is designed to handle PubMed’s vast and diverse dataset, ensuring users can access relevant scientific literature and data for research needs [64].

5.2. Experimentation Setup

The experimental setup utilized a system configuration featuring an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-10750H CPU operating at 2.60GHz, equipped with 16.0GB of RAM, and a 64-bit operating system on an x64-based processor architecture, with graphics processing supported by an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2070 GPU with 8GB of RAM. It also involved configuring a Spyder environment with the transformers library for LLM utilization, setting up GPU support using PyTorch [65], defining a text generation function, and incorporating additional utilities like NumPy [66], Pandas, and logging for comprehensive data manipulation and analysis. In our experimentation, both the local LLM, Gemma [47], and the OpenAI API [36] were utilized; each model was fine-tuned using the same domain-specific PubMed data to ensure a consistent basis for comparison across all models.

5.3. Scenarios

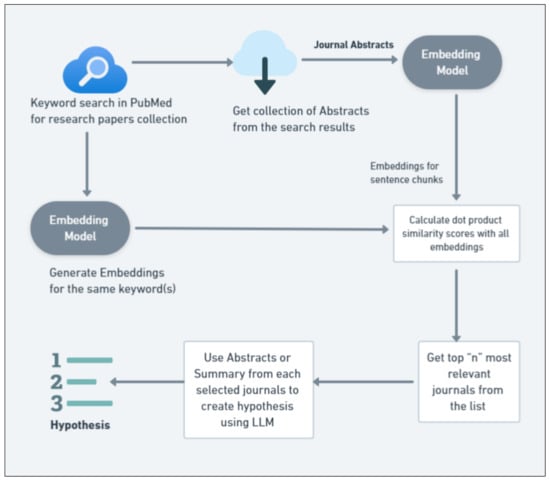

We implement a workflow in these scenarios that integrates advanced text embedding techniques with vector space similarity search. This setup is designed to validate the hypothesis that embedding models can significantly improve the relevance of search results in scholarly databases by capturing the semantic relationships between search queries and document contents. The detailed workflow is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Workflow for semantic similarity search in literature retrieval.

The workflow for embedding-based semantic similarity search in academic literature retrieval starts with a keyword search in PubMed to gather a diverse collection of research papers. From these results, the abstracts are collected for analysis. These abstracts are then transformed into vector embeddings using a pre-trained text embedding model, such as SBERT [60] or a domain-specific model, capturing the semantic content of the texts.

Subsequently, embeddings for the search keywords are generated. The cosine similarity between these keyword embeddings and the abstract embeddings is calculated to assess the semantic closeness of each abstract to the keywords. Similarity scores rank abstracts; the top ’n’ abstracts are selected as the most relevant. The final step uses a language model to synthesize information from the top-ranked abstracts, generating or refining research hypotheses based on the semantic alignment of the most relevant papers, thereby directing further research inquiries more precisely and effectively.

5.3.1. Scenario 1: Validating the Efficacy of Embedding-Based Semantic Similarity Searches in LBD

In this scenario, the efficacy of embedding-based semantic similarity searches in LBD was tested using an LLM, specifically Google/gemma-2b-it [47]. The model generated hypotheses about the effects of garlic on blood pressure, which were then cross-referenced with clinical trial data from ClinicalTrials.gov to assess their scientific relevance and validity. The process involved ranking hypotheses by their semantic relevance and then comparing these hypotheses with data from clinical trials. The validation match scores from ClinicalTrials.gov provided a confidence measure for each hypothesis.

The first hypothesis that garlic significantly reduces blood pressure in hypertensive patients is strongly supported by meta-analyses and high hypothesis weightage scores (0.9398, 0.9325, 0.8883). The validation match score of 0.7989 from clinical trial NCT04915053 confirms its effectiveness, making it the most robustly supported hypothesis. Comparatively, the second hypothesis, suggesting garlic reduces cardiovascular events and mortality, has slightly lower support but still shows high scores (0.9076, 0.8862, 0.8787) and a validation match score of 0.7903 from clinical trial NCT06264622.

The third hypothesis, focusing on garlic’s benefits for blood pressure and inflammation, has solid support with scores (0.8779, 0.8721, 0.8561) and a validation match score of 0.7846 from clinical trial NCT04915053. While all three hypotheses indicate significant benefits, the first is the most strongly supported, followed closely by the second and third.

5.3.2. Scenario 2: Analysis with Different Search Use Cases and Report the Results (Local LLM)

In recent years, the intersection of nutrition and health has gained significant attention, particularly regarding the therapeutic potential of various natural supplements. This scenario explores five distinct use cases that examine the effectiveness of specific dietary components garlic, cinnamon, curcumin, magnesium, and selenium—in managing and improving health outcomes. These use cases aim to identify significant disease relationships through advanced LLM tools. The hypotheses generated for each use case are evaluated based on clinical validity, supported by justifications from meta-analyses, scientific studies, and clinical trials.

Garlic and Blood Pressure: Garlic is widely recognized for its cardiovascular benefits, particularly in reducing blood pressure. This use case investigates the hypothesis that garlic preparations can significantly lower blood pressure in hypertensive individuals, supported by meta-analyses and clinical trials as detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Key search: Garlic reduces blood pressure—Hypotheses and Cross-Referencing Results.

Cinnamon and Diabetes: Cinnamon’s potential in improving glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is well-documented. This use case examines the hypothesis that cinnamon supplementation can enhance glycemic regulation, backed by controlled clinical trials and pre-clinical studies, as detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

“Cinnamon and Diabetes”—Table of hypotheses, supporting research, and validaion scores.

Curcumin and Inflammation: Curcumin, the active compound in turmeric, is known for its anti-inflammatory properties. This use case explores its effectiveness in reducing inflammation, with hypotheses supported by studies showing significant reductions in inflammatory markers, as shown in Table 6 .

Table 6.

“Curcumin and Inflammation”—Hypotheses, supporting research, and validation scores.

Magnesium and Cardiovascular Health: Magnesium’s role in cardiovascular health, particularly in reducing the frequency of ventricular arrhythmias, is the focus of this use case. The hypotheses are supported by studies and clinical trials as depicted in Table 7, demonstrating the benefits of both intravenous and oral magnesium supplementation.

Table 7.

“Magnesium and Cardiovascular Health”—Hypotheses, supporting research, and validation scores.

Selenium and Thyroid Health: Selenium is essential for thyroid function, and its deficiency is linked to various thyroid disorders. This use case evaluates the hypothesis as detailed in Table 8 that selenium supplementation can positively impact thyroid health, supported by studies showing a significant association between selenium levels and thyroid function.

Table 8.

“Selenium and Thyroid Health”—Hypotheses, supporting research, and validation scores.

These use cases collectively highlight the potential of natural supplements in disease prevention and management, offering clinically significant insights that can guide future research and clinical practices.

The summary statistics in Table 9 reveal distinct evidence quality and consistency levels for various natural supplements. Garlic and blood pressure management show the most consistent and high-quality evidence, with a mean score of 0.8932 and a low standard deviation of 0.0214, indicating strong reliability. Cinnamon’s impact on diabetes also demonstrates high reliability, with a mean score of 0.8503 and a low standard deviation of 0.0586, suggesting strong potential for clinical integration.

Table 9.

Summary use case validation scores statistics.

Selenium and thyroid health show consistent evidence, with a mean score of 0.8436 and a standard deviation of 0.0689, underscoring its potential as a valuable intervention in clinical settings. Curcumin and inflammation present more variability, with a mean score of 0.7673 and a standard deviation of 0.0090, indicating a broader range of study results and potential differences in study designs or populations.

Magnesium and cardiovascular health exhibit moderate evidence with a mean score of 0.7398 and a higher standard deviation of 0.0970, highlighting its importance in cardiovascular function but with higher variability than garlic and selenium. Overall, garlic, cinnamon, and selenium emerge as the most reliable supplements with consistent evidence, with their low variability, suggesting strong potential for clinical integration. While curcumin and magnesium show significant potential, they also have considerable support in the literature, suggesting their clinical integration is promising. However, there is a need for further research to enhance consistency across studies.

5.3.3. Scenario 3: Impact of Changing LLM Models on Performance Metrics (Local LLM Model vs. OpenAI Model)

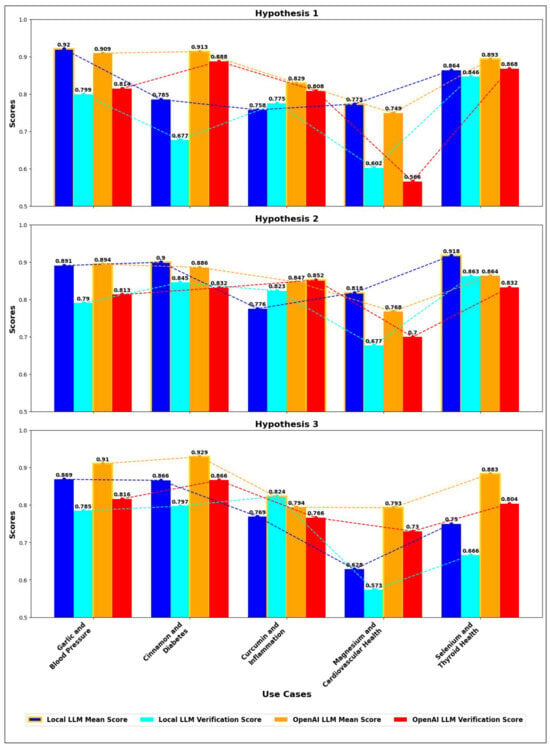

We further tested the same health-related use cases with the OpenAI model, evaluated the performance, and compared it with the local model Google/gemma-2b-it [47], focusing on journal weightage and validation scores for three hypotheses in each use case. For each use case, bar charts were created to visualize the scores as shown in Figure 3, with blue and cyan representing Local LLM journal weightage and validation scores, respectively, and orange and red representing OpenAI LLM journal weightage and validation scores. The journal weightage scores reflect the relevance and citation rate of the models in academic literature, while the validation scores indicate their practical performance and accuracy in real-world applications.

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean journal weightage score and validation scores for Local LLM vs. OpenAI LLM across different hypothesis and use cases.

In the graph comparing the mean and validation scores of Local LLM and OpenAI LLM across different hypotheses, distinct trends emerge for each use case. Garlic, cinnamon, and selenium emerge as the most reliable supplements, with consistent evidence across all three hypotheses. Garlic shows high mean scores, with the Local LLM achieving 0.920, 0.891, and 0.869 across the hypotheses, while OpenAI scores slightly lower but more consistently in validation. Cinnamon demonstrates strong potential for clinical integration with high mean scores (Local LLM: 0.785, 0.900, 0.866 and OpenAI: 0.913, 0.886, 0.929) and relatively consistent validation scores. Selenium shows consistent evidence, highlighting its value in thyroid health, with Local LLM scores at 0.864, 0.918, and 0.750, and OpenAI scores at 0.893, 0.864, and 0.883. Curcumin and magnesium exhibit significant potential but require further research to enhance consistency across studies. Thus, OpenAI generally provides more consistent validation, while Local LLM often predicts higher evidence quality, indicating a trade-off between prediction quality and reliability across different hypotheses and use cases. In general, while Local LLM often predicts higher mean scores, suggesting a perception of higher evidence quality, OpenAI generally achieves higher validation scores, indicating greater consistency and reliability in its predictions across various use cases. This trade-off between prediction quality and validation consistency is crucial for evaluating the practical application of these models.

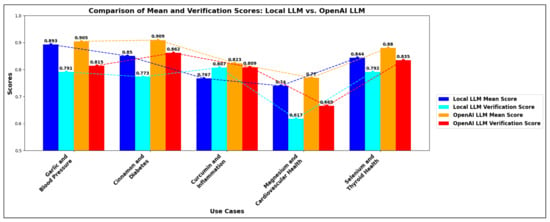

5.3.4. Scenario 4: Comprehensive Comparison of the Performance: Local LLM vs. OpenAI

The graph in Figure 4 comprehensively compares the performance between Local LLM and OpenAI LLM across five use cases. Both models demonstrate varying levels of reliability in hypothesis generation. In the use cases of “Garlic and Blood Pressure” and “Cinnamon and Diabetes”, OpenAI’s mean scores are marginally higher than those of Local LLM, indicating better performance. Specifically, for “Garlic and Blood Pressure”, OpenAI scores 0.905 compared to Local LLM’s 0.893, and for “Cinnamon and Diabetes”, OpenAI scores 0.909 compared to Local LLM’s 0.850.

Figure 4.

Local LLM vs. OpenAI Model—Performance comparison.

The use case “Magnesium and Cardiovascular Health” shows moderate scores, where both Local LLM and OpenAI exhibit mean scores around 0.7 to 0.8, which, while decent, are not as high as those observed in other use cases. This indicates that the evidence for magnesium’s benefits on cardiovascular health, while present, could be more robust and consistent compared to other supplements evaluated in the study.

The comparison reveals a clear overall trend: the OpenAI model consistently outperforms the Local LLM model across all evaluated use cases, as seen in Figure 4. This superiority is evident in mean and validation scores, indicating that the OpenAI model has a more robust and accurate understanding of the relationships between various disease-remedy pairs. The performance gap is especially pronounced in use cases involving complex interactions, such as the anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin and the management of diabetes with cinnamon. However, even in areas where the Local LLM model performs relatively well, such as the effects of selenium on thyroid health, the OpenAI model still maintains a noticeable edge. This trend underscores the OpenAI model’s advantage, likely stemming from its extensive training data and advanced algorithms. It is a more reliable choice for accurate predictions and insights across diverse health-related topics. Nevertheless, when the OpenAI model is inaccessible, the Local LLM model performs competently in many areas, providing a viable alternative for generating valuable predictions and insights.

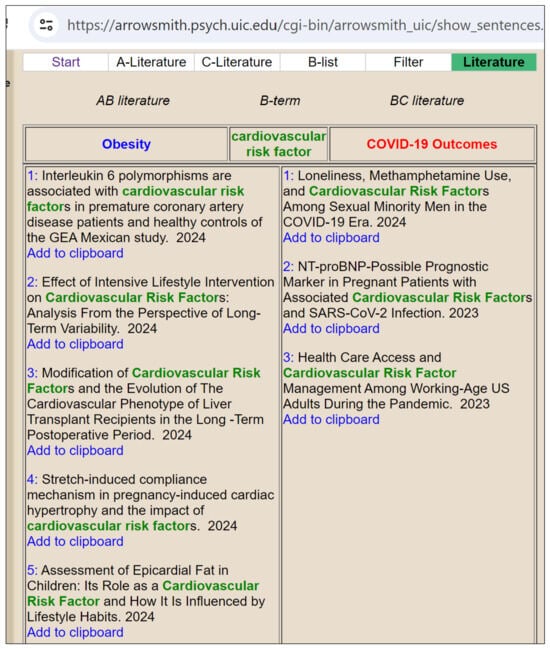

5.3.5. Scenario 5: Comparative Analysis with Swanson’s ABC Model

To compare the effectiveness of an LLM-powered agent with Swanson’s ABC model in discovering hidden relationships between diseases, we present the results of both models.

Figure 5 demonstrates the use of the Swanson model test from Arrowsmith, where the A-query is “Obesity”, the C-query is “COVID-19 Outcomes”, and the intermediary B-term is “Cardiovascular Risk Factor”. The AB literature includes research articles linking obesity with cardiovascular risk factors, such as studies on interleukin6 polymorphisms, intensive lifestyle interventions, and epicardial fat assessment.

Figure 5.

Demonstrating Swanson Model.

The BC literature encompasses research articles connecting cardiovascular risk factors with COVID-19 outcomes, including studies on loneliness and methamphetamine use, NT-proBNP as a prognostic marker, and healthcare access during the pandemic. This model identifies cardiovascular risk factors as a bridge linking obesity and COVID-19 outcomes, revealing potential biological and clinical connections.

Table 10 presents hypotheses generated by our LLM-based LBD approach, linking obesity with cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes associated with COVID-19, each justified by specific risk factors, supported by PMID scores, and verified through clinical trials. It highlights how weight gain, higher BMI, and obesity contribute to increased CVD risk in the context of COVID-19.The Swanson model and the LLM-based Literature-Based Discovery (LBD) approach aim to uncover hidden relationships in scientific literature. Still, they do so in fundamentally different ways, each with strengths and limitations. The Swanson extracts titles and phrases containing standard terms to reveal potential biological relationships. For instance, it may link obesity, cardiovascular risk factors, and COVID-19 outcomes by identifying common terms in related research articles, and manual intervention is needed to decide the common term.

Table 10.

LBD using LLM—Use case—Obesity, Cardiovascular risk factor, COVID-19 Outcomes.

The output of the Swanson model is a list of titles from the literature showing associations, such as the relationship between obesity and cardiovascular risk factors and how these may relate to COVID-19 outcomes. However, the Swanson model does not formulate specific hypotheses or provide detailed justifications for the identified relationships. Instead, it highlights general associations found in the literature, leaving the interpretation and hypothesis generation to the researchers.

In contrast, the LLM-based LBD approach generates specific hypotheses based on the relationships between variables and supports these with detailed justifications. This method utilizes literature and clinical trial data to provide hypotheses and their validation. For example, the LLM-based LBD might propose that weight gain during the pandemic increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) associated with COVID-19 or that obesity is an independent risk factor for CVD in the context of COVID-19. Each hypothesis is backed by specific studies (PMIDs) and clinical trial validation, providing a robust framework for understanding and exploring these relationships.

5.4. Results, Discussion and Limitations

Integrating LLMs into LBD significantly enhances traditional methods, such as the Swanson model, by providing detailed and actionable hypotheses with robust validation. Unlike the Swanson model, which broadly connects literature through standard terms, the LLM-based approach generates specific hypotheses backed by extensive datasets and clinical trials. This method effectively demonstrated scenarios involving obesity, cardiovascular risk factors, and COVID-19 outcomes, as well as the impact of nutritional supplements such as garlic, cinnamon, curcumin, magnesium, and selenium. Additionally, comparisons between local LLM models and OpenAI’s model highlighted the superior reliability and accuracy of OpenAI’s. The validation scores, calculated using cosine similarity between hypothesis embeddings and trial embeddings from ClinicalTrials.gov, quantify the alignment of generated hypotheses with real-world clinical data. These scores serve as a proxy for traditional metrics like precision and recall, effectively substantiating the claims of improved efficiency and discovery depth. To enhance transparency and explainability, the model outputs are linked to specific PubMed IDs, allowing researchers to trace generated hypotheses back to their supporting literature. This connection between predictions and primary sources increases trust in the model’s results and facilitates further investigation by researchers.

Our approach to data sampling for our experimentation included literature selection, which involved querying the PubMed APIs and refining results through a combination of heuristic methods, such as semantic keyword searches and prioritization based on citation counts, to ensure relevance and quality. For instance, for the case study on examining the effects of garlic on blood pressure, keywords such as ’garlic’, ’hypertension’, and ’blood pressure’ were employed to retrieve relevant abstracts. Although a larger set of abstracts was curated for comprehensive domain coverage, the LLM focused on the most relevant studies during hypothesis generation, ensuring that the derived hypotheses were precise, evidence-backed, and aligned closely with the research question.

Although our study validates the integration of LLMs into the LBD process across several biomedical domains, there are limitations to the current application scope. Specifically, it has yet to be applied to more complex global health issues, such as the seasonal patterns of COVID-19. For instance, applying our framework to analyze the hypothesis on seasonality of SARS-CoV-2, as discussed in AA VV’s Fourier spectral analysis [67], could further demonstrate its utility in addressing practical, timely and intricate biomedical challenges. Moreover, the framework has the potential to be expanded beyond biomedical research to other interdisciplinary domains, such as global health, environmental science, and social sciences, where it can uncover novel connections and generate valuable insights. Therefore, the LLM-enhanced approach not only accelerates the discovery process and enhances the generation of insights, but also stands as a powerful tool for advancing interdisciplinary scientific research.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study has explored the integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into the traditional Literature-Based Discovery (LBD) framework, demonstrating significant improvements in the scalability and depth of the discovery process. By leveraging LLMs’ advanced capabilities in natural language understanding and hypothesis generation, we have automated and accelerated identifying novel connections within vast biomedical literature. Our proposed model, which incorporates LLMs with robust data cleansing and semantic enhancement tools, has shown promising results, significantly enhancing the efficiency and precision of hypothesis generation.

Key findings include the effective generation of hypotheses, improved data processing through advanced techniques like SBERT for sentence embeddings, and LLMs’ scalable and efficient nature in processing large volumes of literature. In addition to these advances, the framework redefines traditional LBD boundaries by introducing continuous learning capabilities and domain-specific fine-tuning, enabling real-time adaptation to evolving scientific fields and ensuring ongoing relevance in the discovery process.

Future work would focus on refining LLM techniques, including Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and LLM agents, to mitigate hallucination and enhance accuracy. Additionally, the framework could be adapted for other interdisciplinary domains, such as social sciences, personalized medicine, rare disease research, and drug repurposing, where it could uncover novel insights and drive impactful discoveries. Furthermore, developing user-friendly interfaces with robust verification mechanisms would improve usability and ensure factual accuracy.

Author Contributions

I.T. conceived the main conceptual ideas related to the LLM-enhanced Literature-Based Discovery framework, including the architecture, the literature review, and the overall implementation and execution of the experiments. A.N.N. contributed significantly to the design and integration of LLMs with semantic enhancement tools and data cleansing processes, and played a vital role in the empirical validations and analysis of the results. M.A.S. contributed to the overall architecture of the model, ensured the study was conducted with utmost care and attention to detail, and oversaw the overall direction and planning of the research. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by Zayed University RIF Grant: R22017.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on PubMed, managed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 2 July 2024. Additional datasets generated and analyzed during the study are available in publicly archived repositories available at https://clinicaltrials.gov.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Madhu Chaliyan for his contribution to the project implementation and experimentation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| EMNLP | Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| LBD | Literature-Based Discovery |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PMID | PubMed Identifier |

| RTX | Ray Tracing Texel eXtreme |

| SBERT | Sentence-BERT |

| Se | Selenium |

References

- Swanson, D.R. Fish oil, Raynaud’s syndrome, and undiscovered public knowledge. Perspect. Biol. Med. 1986, 30, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeber, M.; Klein, H.; De Jong-Van Den Berg, L.T.W.; Vos, R. Using concepts in literature-based discovery: Simulating Swanson’s Raynaud-fish oil and migraine-magnesium discoveries. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2001, 52, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165. [Google Scholar]

- Tophel, A.; Chen, L. Towards an AI Tutor for Undergraduate Geotechnical Engineering : A Comparative Study of Evaluating the Efficiency of Large Language Model Application Programming Interfaces. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tophel, A.; Hettiyadura, U.; Kodikara, J. An Investigation into the Utility of Large Language Models in Geotechnical Education and Problem Solving. Geotechnics 2024, 4, 470–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünau, P.V. From the Depths of Literature: How Large Language Models Excavate Crucial Information to Scale Drug Discovery, 2023. Available online: https://idalab.de/insights/how-large-language-models-excavate-crucial-information-to-scale-drug-discovery (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Smalheiser, N.R.; Swanson, D.R. Using ARROWSMITH: A computer-assisted approach to formulating and assessing scientific hypotheses. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 1998, 57, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Heo, G.; Ding, Y. SemPathFinder: Semantic path analysis for discovering publicly unknown knowledge. J. Inf. 2015, 9, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetisgen-Yildiz, M. LitLinker: A system for searching potential discoveries in biomedical literature. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Seattle, WA, USA, 6–11 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Choi, J.; Park, K.; Song, M.; Lee, D. Discovering context-specific relationships from biological literature by using multi-level context terms. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Giglou, H.B.; Malik, K.M. Automated clinical knowledge graph generation framework for evidence based medicine. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 233, 120964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, B.; Minervini, P.; Stenetorp, P.; Riedel, S. An Efficient Memory-Augmented Transformer for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 5184–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A.K.; Srinivasan, P. Manjal: A text mining system for MEDLINE. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Salvador, Brazil, 15–19 August 2005; p. 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.H.; Lee, D.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.; Song, M. Enriching plausible new hypothesis generation in PubMed. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Searls, D.B. Literature mining in support of drug discovery. Briefings Bioinform. 2008, 9, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crichton, G.; Baker, S.; Guo, Y.; Korhonen, A. Neural networks for open and closed Literature-based Discovery. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Hristovski, D.; Schutte, D.; Kastrin, A.; Fiszman, M.; Kilicoglu, H. Drug repurposing for COVID-19 via knowledge graph completion. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 115, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordons, I.; Morillo, F.; Gómez, I. Analysis of Cross-Disciplinary Research Through Bibliometric Tools; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia, C.; Kajikawa, Y. A network approach for mapping and classifying shared terminologies between disparate literatures in the social sciences. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), Singapore, 11–14 May 2020; Volume 12237, pp. 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.; Wijesinghe, D.S.; Myers, A.; McInnes, B.T. Using Literature Based Discovery to Gain Insights into the Metabolomic Processes of Cardiac Arrest. Front. Res. Metrics Anal. 2021, 6, 644728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Škrlj, B.; Kokalj, E.; Lavrač, N. PubMed-Scale Chemical Concept Embeddings Reconstruct Physical Protein Interaction Networks. Front. Res. Metrics Anal. 2021, 6, 644614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrouti, M.; Ouatik El Alaoui, S. A passage retrieval method based on probabilistic information retrieval and UMLS concepts in biomedical question answering. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017, 68, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedbaylo, A.; Hristovski, D. Implementing Literature-based Discovery (LBD) with ChatGPT. In Proceedings of the 2024 47th ICT and Electronics Convention, MIPRO 2024—Proceedings, Opatija, Croatia, 20–24 May 2024; pp. 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Jha, K.; Jin, W.; Zhang, A. A survey on literature based discovery approaches in biomedical domain. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 93, 103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Gholami, M.H.; Hashemi, F.; Zabolian, A.; Farahani, M.V.; Hushmandi, K.; Zarrabi, A.; Goldman, A.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Orive, G. Advances in understanding the role of P-gp in doxorubicin resistance: Molecular pathways, therapeutic strategies, and prospects. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Bonifield, G.; Smalheiser, N.R. Gaps within the Biomedical Literature: Initial Characterization and Assessment of Strategies for Discovery. Front. Res. Metrics Anal. 2017, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Downey, D.; Ji, H.; Hope, T. SCIMON: Scientific Inspiration Machines Optimized for Novelty. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.14259. [Google Scholar]

- Preiss, J. Avoiding background knowledge: Literature based discovery from important information. BMC Bioinform. 2022, 23, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, D.D.; Dhotre, D.R.; Gawande, G.S.; Mate, D.S.; Shelke, M.V.; Bhoye, T.S. Transformative Trends in Generative AI: Harnessing Large Language Models for Natural Language Understanding and Generation. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 2024, 12, 309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Prather, J.; Denny, P.; Leinonen, J.; Becker, B.A.; Albluwi, I.; Craig, M.; Keuning, H.; Kiesler, N.; Kohn, T.; Luxton-Reilly, A.; et al. The Robots Are Here: Navigating the Generative AI Revolution in Computing Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 Working Group Reports on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education, Turku, Finland, 7–12 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, O.; Nguyen, H.L.; Rampal, N.; Alawadhi, A.H.; Rong, Z.; Head-Gordon, T.; Borgs, C.; Chayes, J.T.; Yaghi, O.M. ChatGPT Research Group for Optimizing the Crystallinity of MOFs and COFs. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 2161–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannantuono, G.M.; Bracken-Clarke, D.; Floudas, C.S.; Roselli, M.; Gulley, J.L.; Karzai, F. Applications of large language models in cancer care: Current evidence and future perspectives. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1268915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, P.; Kim, K.; Acharya, M. Opportunities and Challenges of Generative AI in Construction Industry: Focusing on Adoption of Text-Based Models. Buildings 2024, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhane, A.; Kasirzadeh, A.; Leslie, D.; Wachter, S. Science in the age of large language models. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2023, 5, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka, M.; Wysocki, O.; Delmas, M.; Mutel, V.; Freitas, A. Large Language Models scientific knowledge and factuality: A systematic analysis in antibiotic discovery. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.17819. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. GPT-4. 2024. Available online: https://openai.com/research/gpt-4 (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.; Kardas, M.; Cucurull, G.; Scialom, T.; Hartshorn, A.; Saravia, E.; Poulton, A.; Kerkez, V.; Stojnic, R. Galactica: A Large Language Model for Science. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.09085. [Google Scholar]

- Workshop, B.; Scao, T.L.; Fan, A.; Akiki, C.; Pavlick, E.; Ilić, S.; Hesslow, D.; Castagné, R.; Luccioni, A.S.; Yvon, F.; et al. BLOOM: A 176B-Parameter Open-Access Multilingual Language Model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.05100. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, R.; Sun, L.; Xia, Y.; Qin, T.; Zhang, S.; Poon, H.; Liu, T.Y. BioGPT: Generative Pre-trained Transformer for Biomedical Text Generation and Mining. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. PaLM: Scaling Language Modeling with Pathways. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Ding, S.; Gong, W.; Feng, S.; Shang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Pang, C.; et al. ERNIE 3.0 Titan: Exploring Larger-scale Knowledge Enhanced Pre-training for Language Understanding and Generation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.12731. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft. Turing-NLG: A 17-Billion-Parameter Language Model by Microsoft. 2020. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/turing-nlg-a-17-billion-parameter-language-model-by-microsoft/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, D.; Shoeybi, M.; Casper, J.; LeGresley, P.; Patwary, M.; Korthikanti, V.; Vainbrand, D.; Kashinkunti, P.; Bernauer, J.; Catanzaro, B.; et al. Efficient Large-Scale Language Model Training on GPU Clusters Using Megatron-LM. Assoc. Comput. Mach. 2021, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2019—2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019, Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. Available online: http://xxx.lanl.gov/abs/1810.04805 (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Google. Gemma: 2B. 2023. Available online: https://huggingface.co/google/gemma-2b-it (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Binz, M.; Schulz, E. Turning large language models into cognitive models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.03917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyko, J.; Cohen, J.; Fox, N.; Veiga, M.H.; Li, J.I.; Liu, J.; Modenesi, B.; Rauch, A.H.; Reid, K.N.; Tribedi, S.; et al. An Interdisciplinary Outlook on Large Language Models for Scientific Research. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.04929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, D.A.; Macknight, R.; Gomes, G. Emergent autonomous scientific research capabilities of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.05332. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Koh, H.Y.; Ju, J.; Nguyen, A.T.; May, L.T.; Webb, G.I.; Pan, S. Large Language Models for Scientific Synthesis , Inference and Explanation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.07984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, G.; Shi, P.; Zhao, C.; Xu, H.; Ye, Q.; Yan, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.; et al. Evaluation and Analysis of Hallucination in Large Vision-Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.15126. [Google Scholar]

- Birkun, A.K.; Gautam, A. Large Language Model (LLM)-Powered Chatbots Fail to Generate Guideline-Consistent Content on Resuscitation and May Provide Potentially Harmful Advice. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2023, 38, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, N.; Li, T.; Cheng, L.; Hosseini, M.J.; Johnson, M.; Steedman, M. Sources of Hallucination by Large Language Models on Inference Tasks. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.14552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Questions, O.; Yu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Peng, W.; Feng, X.; Qin, B.; et al. A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.05232. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Cai, D.; Liu, L.; Fu, T.; Huang, X.; Zhao, E.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Siren’s Song in the AI Ocean: A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.01219. [Google Scholar]

- Quantization. 2024. Available online: https://huggingface.co/docs/optimum/en/concept_guides/quantization (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Tabassum, A.; Patil, R.R. A Survey on Text Pre-Processing & Feature Extraction Techniques in Natural Language Processing. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2020, 7, 4864–4867. [Google Scholar]

- spaCy. Industrial-Strength Natural Language Processing in Python. 2024. Available online: https://spacy.io/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using siamese BERT-networks. In Proceedings of the EMNLP-IJCNLP 2019—2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 3982–3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Harandi, M.; Nock, R.; Hartley, R. Siamese networks: The tale of two manifolds. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3046–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- PubMed—National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Sayers, E.W.; Barrett, T.; Benson, D.A.; Bryant, S.H.; Canese, K.; Chetvernin, V.; Church, D.M.; DiCuccio, M.; Edgar, R.; Federhen, S.; et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D10–D17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An imperative style high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 8026–8037. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Walt, S.; Colbert, S.C.; Varoquaux, G. The NumPy array: A structure for efficient numerical computation. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2011, 13, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappi, R.; Casini, L.; Tosi, D.; Roccetti, M. Questioning the seasonality of SARS-COV-2: A Fourier spectral analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e061602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).