#lockdown: Network-Enhanced Emotional Profiling in the Time of COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Aim

1.2. Past Approaches Bridging Cognitive, Computer and Network Science

1.3. Main Contributions

1.4. Manuscript Outline

2. Methods

2.1. Data

- #iorestoacasa (English: “I stay at home“), a positive-sentiment hashtag introduced by the Italian Government in order to promote a responsible attitude during the lockdown;

- #sciacalli, (English: “jackals“), a negative sentiment hashtag used by online users in order to address unfair behaviour rising during the health emergency;

- #italylockdown, a neutral sentiment hashtag indicating the application of lockdown measures all over Italy.

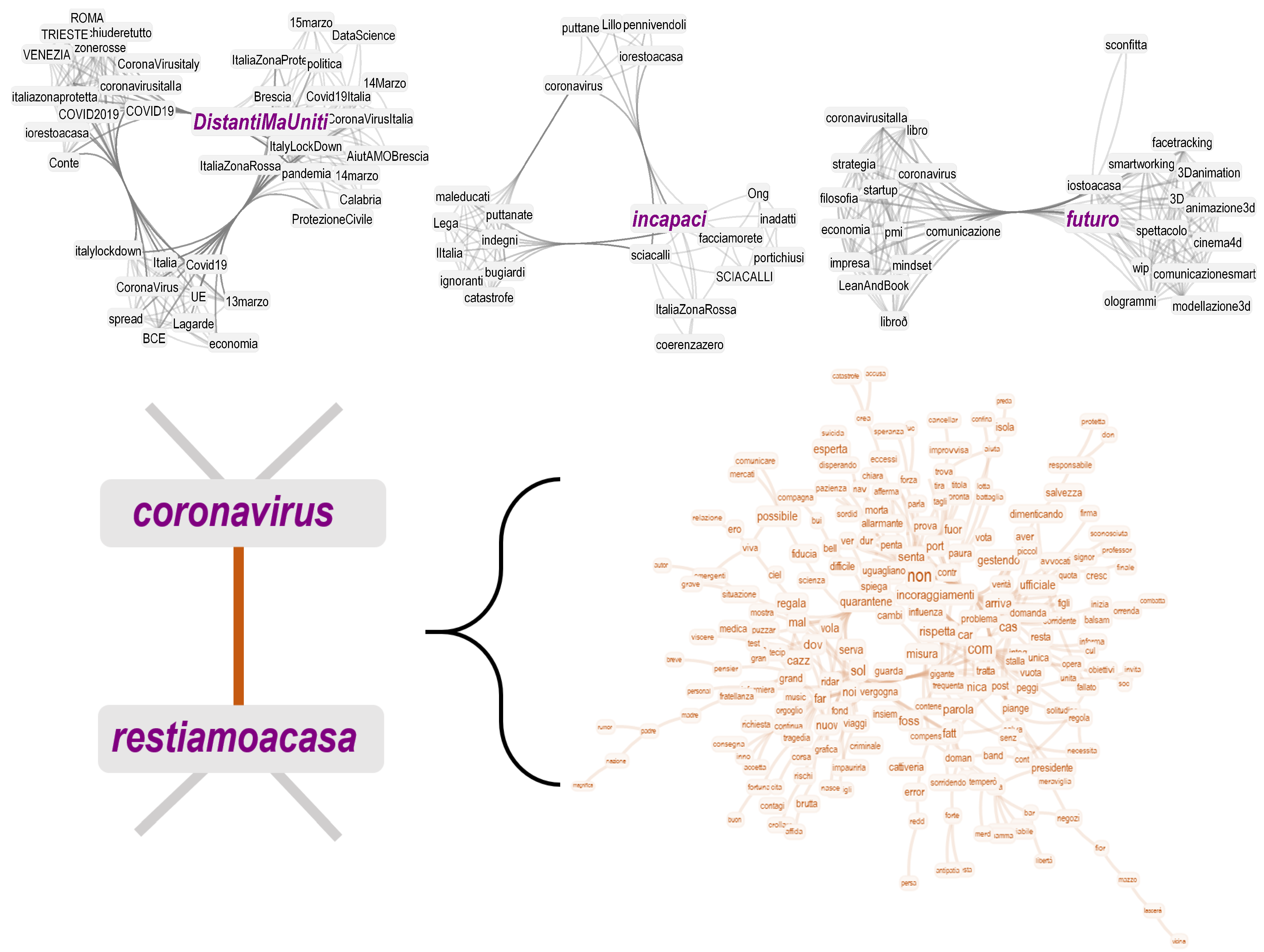

2.2. Multi-Layer Co-Occurrence Networks

- Hashtag co-occurrence networks (or hashtag networks) [12]. Nodes represent hashtags and links indicate the co-occurrence of any two nodes in the same tweet.

- Word co-occurrence networks (or word networks) [16]. Nodes represent words and links represent the co-occurrence of any two words one after the other in a tweet without stop-words (i.e., words without an intrinsic meaning).

2.3. Attributing Meaning and Emotions to Focal Hashtags by Using Word Networks

- Subdivide the tweet in sentences and delete all stop-words from each sentence, preserving the original ordering of words;

- Stem all the remaining words, that is, identify the root or stem composing a given word. In a language such as Italian, in which there is a number of ways of adding suffixes to words, word stemming is essential in order to recognise the same word even when it is inflected for different gender, number or as a verb tense. For instance, abbandoneremo (we will abandon) and abbandono (abandon, abandonment) both represent the same stem abband;

- Draw links between a stemmed word and its subsequent one. Store the resulting edge list of word co-occurrences.

- Sentences containing a negation (i.e., “not“) underwent an additional step parsing their syntactic structure. This was done in order to identify the target of negation (e.g., in “this is not peace“, the negation refers to “peace“). Syntactic dependencies were not used for network construction but intervened in emotional profiling, instead (see below).

2.4. Emotional Profiling

3. Results

3.1. Conceptual Relevance in Hashtag Networks

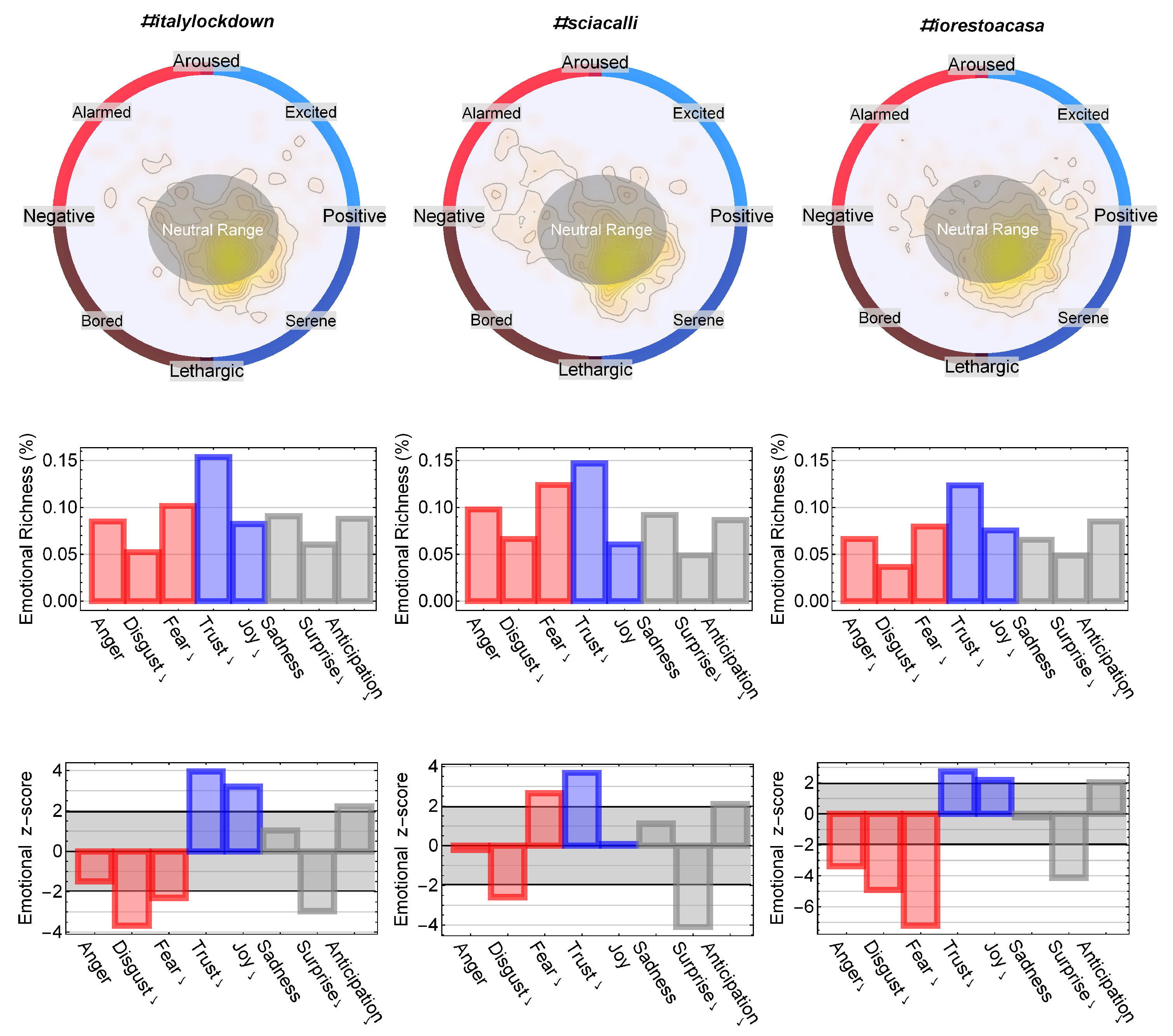

3.2. Emotional Profiling of Hashtag Networks

3.2.1. Emotional Profiling of Hashtag Networks through the Circumplex Model

3.2.2. Emotional Profiling of Hashtag Networks through Basic Emotions

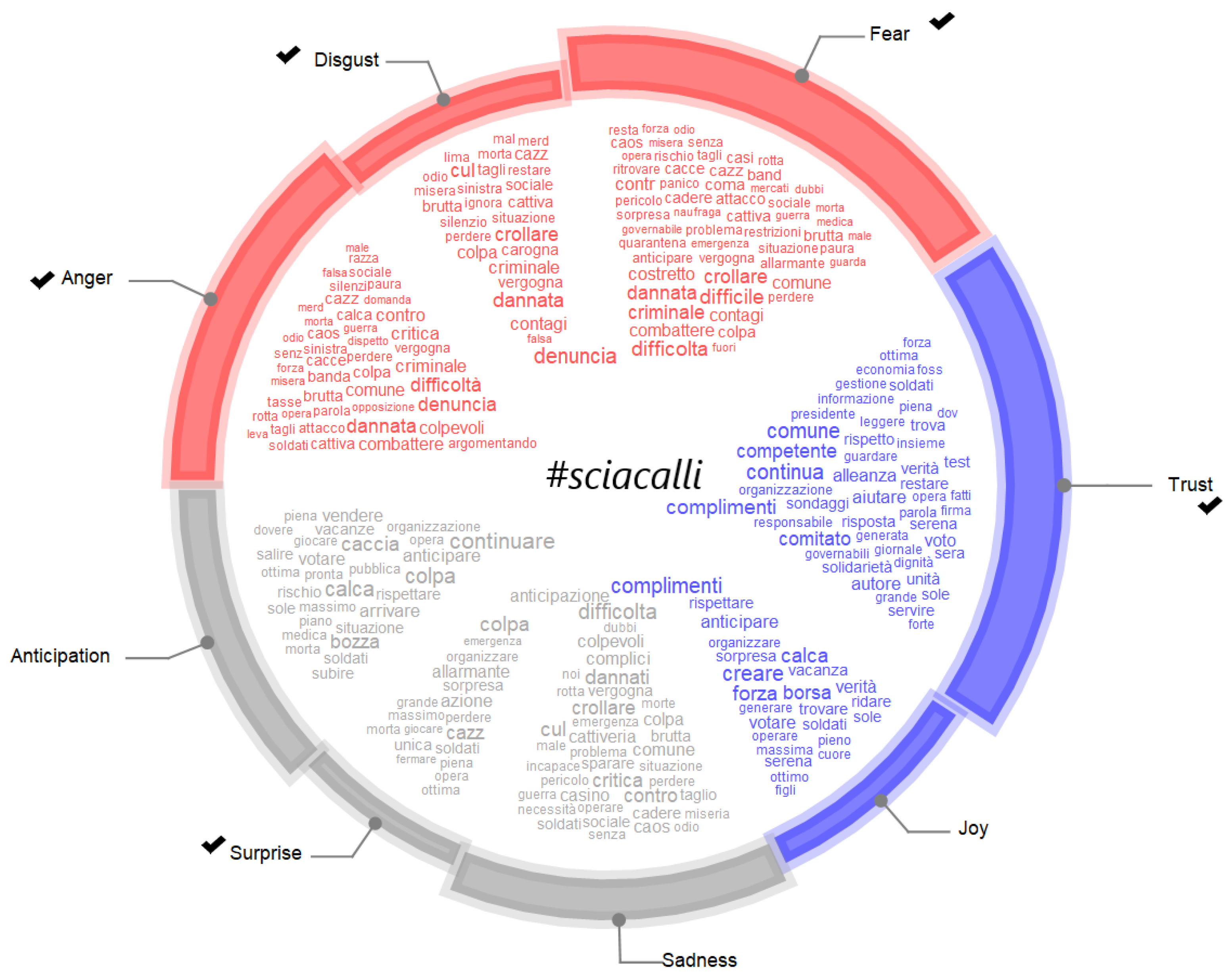

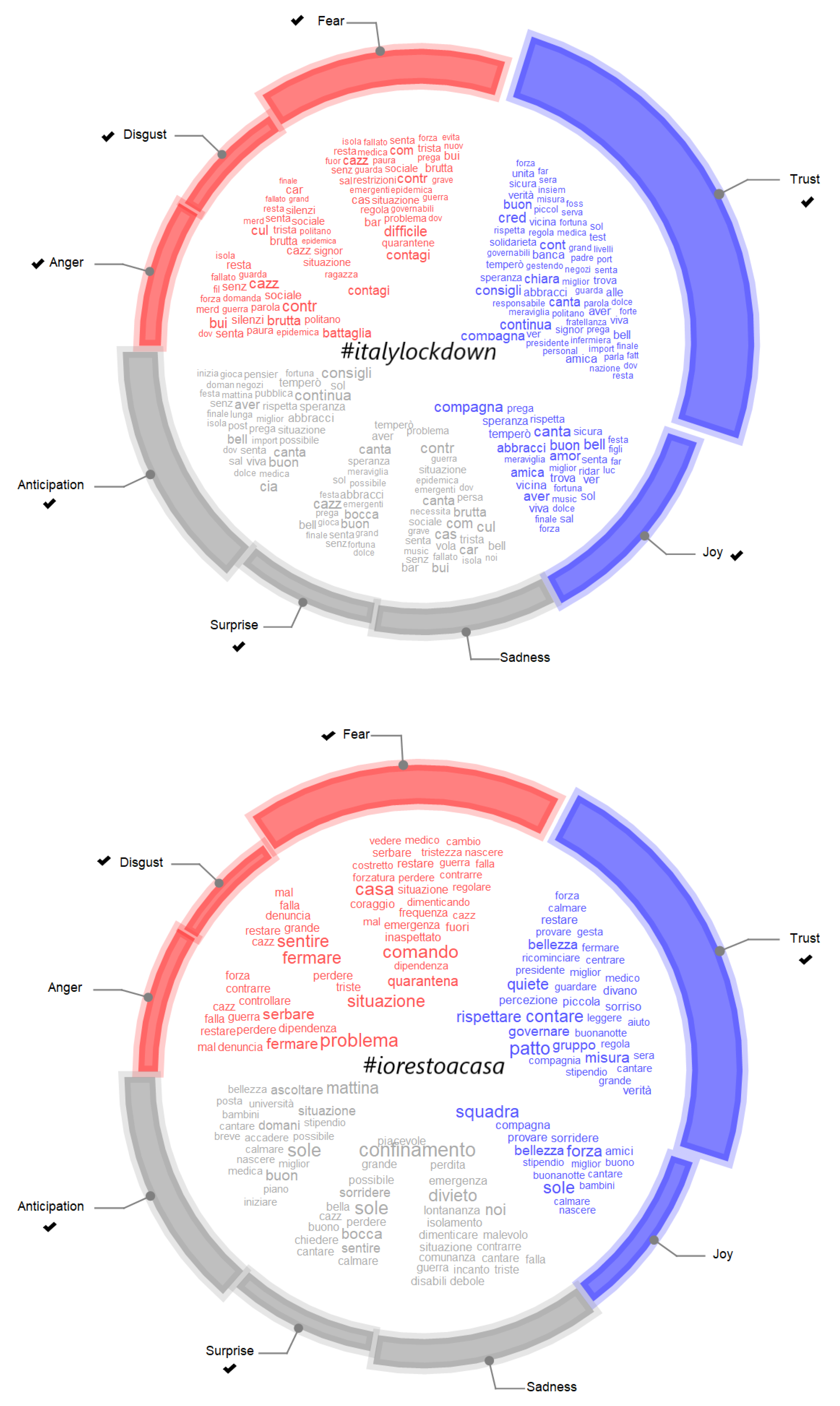

3.3. Assessing Conceptual Relevance and Emotional Profiles of Hashtags via Word Networks

- a fearful denunciation of criminal acts with political nuances and sadness/desperation about negative economic repercussions (from #sciacalli);

- positive and trustful externalisations of fraternity and affect, combined with hopeful attitudes towards a better future (from #italylockdown and #iorestoacasa);

- a mournful concern about the psychological weight of being confined at home, inspiring sadness and disgust towards the health emergency (from #iorestoacasa).

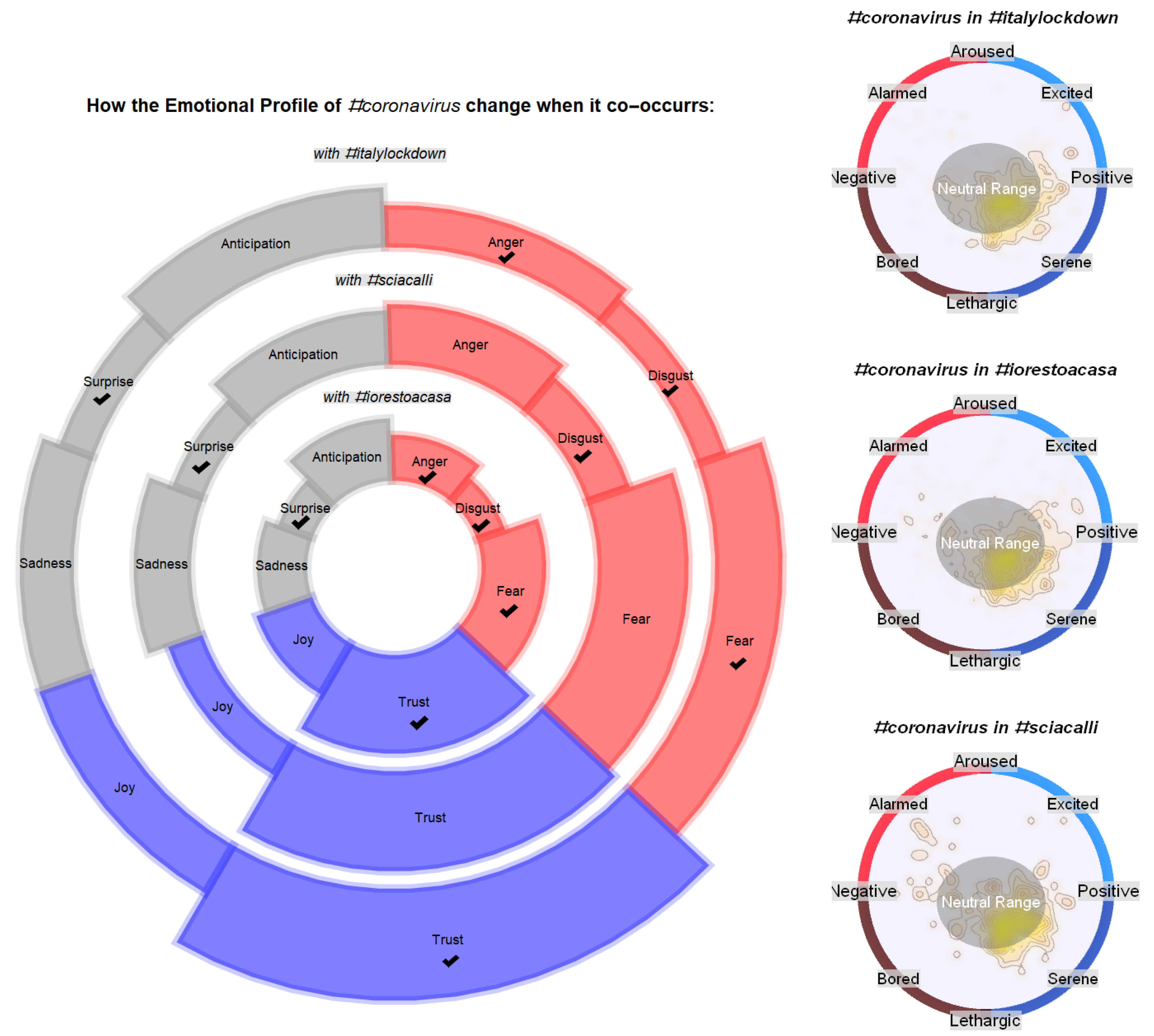

3.4. Hashtag Co-Occurrence Contextually Influences Hashtag Emotional Profiles

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Cognitive Network Science for Social Media Analysis

4.2. Evidence for Emotional Polarisation around COVID-19

4.3. Implications of the Detected Anger and Fear over Self-Awareness and Violence

4.4. Contextual Shifts in Emotions around the Novel Coronavirus

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

6. Data Availability

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zarocostas, J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Galeazzi, A.; Valensise, C.M.; Brugnoli, E.; Schmidt, A.L.; Zola, P.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A. The covid-19 social media infodemic. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.05004. [Google Scholar]

- Gallotti, R.; Valle, F.; Castaldo, N.; Sacco, P.; De Domenico, M. Assessing the risks of “infodemics“ in response to COVID-19 epidemics. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.03997. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, C.M.; Villarejo-Carballido, B.; Redondo-Sama, G.; Gomez, A. COVID-19 infodemic: More retweets for science-based information on coronavirus than for false information. Int. Soc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.; Ho, R. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health During COVID-19 Outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Hong, W.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. The immediate mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among people with or without quarantine managements. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Mclntyre, R.; Choo, F.; Tran, B.; Ho, R.; Sharma, V.; et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E.; Yang, Z. Quantifying the effect of sentiment on information diffusion in social media. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2015, 1, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.T.; Perra, N.; Zhang, Q.; Moreno, Y.; Vespignani, A. Phase transitions in information spreading on structured populations. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulla, F.; Mocanu, D.; Baronchelli, A.; Gonçalves, B.; Perra, N.; Vespignani, A. Beating the news using social media: The case study of American Idol. EPJ Data Sci. 2012, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.; Ferrara, E.; De Domenico, M. Bots increase exposure to negative and inflammatory content in online social systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 12435–12440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bail, C.A.; Argyle, L.P.; Brown, T.W.; Bumpus, J.P.; Chen, H.; Hunzaker, M.F.; Lee, J.; Mann, M.; Merhout, F.; Volfovsky, A. Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9216–9221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siew, C.S.; Wulff, D.U.; Beckage, N.M.; Kenett, Y.N. Cognitive Network Science: A review of research on cognition through the lens of network representations, processes, and dynamics. Complexity 2019, 2019, 2108423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M. Text-mining forma mentis networks reconstruct public perception of the STEM gender gap in social media. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.08835. [Google Scholar]

- Amancio, D.R. Probing the topological properties of complex networks modeling short written texts. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quercia, D.; Kosinski, M.; Stillwell, D.; Crowcroft, J. Our twitter profiles, our selves: Predicting personality with twitter. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Privacy, Security, Risk and Trust and 2011 IEEE Third International Conference on Social Computing; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, S.M.; Turney, P.D. Emotions evoked by common words and phrases: Using mechanical turk to create an emotion lexicon. In Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2010 Workshop on Computational Approaches to Analysis and Generation of Emotion in Text; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, P.S.; Harris, K.D.; Kloumann, I.M.; Bliss, C.A.; Danforth, C.M. Temporal patterns of happiness and information in a global social network: Hedonometrics and Twitter. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.; Bravo-Marquez, F.; Salameh, M.; Kiritchenko, S. Semeval-2018 task 1: Affect in tweets. In Proceedings of the 12th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–6 June 2018; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinberg, B.; van der Vegt, I.; Mozes, M. Measuring Emotions in the COVID-19 Real World Worry Dataset. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.04225. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, A.C.M.; Silva, F.N.; Amancio, D.R. A complex network approach to political analysis: Application to the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutchik, R. The Emotions; University Press of America: Lanham, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.E.; Davidson, R.J. The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Rapson, R.L. Emotional contagion. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 1993, 2, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G. The ripple effect: Emotional contagion and its influence on group behavior. Adm. Sci. Quart. 2002, 47, 644–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.D.; Guillory, J.E.; Hancock, J.T. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8788–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, S.; Donnay, K.; Helbing, D.; Sumner, R.W.; Bos, M.W. The rippling dynamics of valenced messages in naturalistic youth chat. Behavi. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 1737–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasper, J.M. Emotions and social movements: Twenty years of theory and research. Ann. Rew. Soc. 2011, 37, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.; De Nigris, S.; Aloric, A.; Siew, C.S. Forma mentis networks quantify crucial differences in STEM perception between students and experts. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, J.; Russell, J.A.; Peterson, B.S. The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2005, 17, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Deyne, S.; Kenett, Y.N.; Anaki, D.; Faust, M.; Navarro, D.J. Large-scale network representations of semantics in the mental lexicon. In Big Data in Cognitive Science: From Methods to Insights; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 174–202. [Google Scholar]

- Stella, M.; Zaytseva, A. Forma mentis networks map how nursing and engineering students enhance their mindsets about innovation and health during professional growth. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2020, 6, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehler, A.; Gleim, R.; Gaitsch, R.; Hemati, W.; Uslu, T. From Topic Networks to Distributed Cognitive Maps: Zipfian Topic Universes in the Area of Volunteered Geographic Information. Complexity 2020, 2020, 4607025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, M.; De Domenico, M. Distance entropy cartography characterises centrality in complex networks. Entropy 2018, 20, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Lerman, K.; Ferrara, E. Tracking Social Media Discourse About the COVID-19 Pandemic: Development of a Public Coronavirus Twitter Data Set. JMIR Pub. Health Surv. 2020, 6, e19273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, V.Q.; Hirst, G.; Amancio, D.R. Labelled network subgraphs reveal stylistic subtleties in written texts. J. Complex Netw. 2018, 6, 620–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankrunkelsven, H.; Verheyen, S.; Storms, G.; De Deyne, S. Predicting lexical norms: A comparison between a word association model and text-based word co-occurrence models. J. Cogn. 2018, 1, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M. Networks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stella, M. Modelling early word acquisition through multiplex lexical networks and machine learning. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2019, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warriner, A.B.; Kuperman, V.; Brysbaert, M. Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 English lemmas. Behav. Res. Methods 2013, 45, 1191–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, M.M.; Kenny, D.T.; Davis, P.J. The effects of group singing on mood. Psychol. Music 2002, 30, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Gergely, G.; Jurist, E.L. Affect Regulation, Mentalization and the Development of the Self; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stella, M. Forma mentis networks reconstruct how Italian high schoolers and international STEM experts perceive teachers, students, scientists, and school. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A. WordNet: An Electronic Lexical Database; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, N.; Stella, M. The multiplex structure of the mental lexicon influences picture naming in people with aphasia. J. Compl. Netw. 2019, 7, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnoli, E.; Cinelli, M.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Scala, A. Recursive patterns in online echo chambers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, J. On the perception of social consensus. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 30, pp. 163–240. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, E.; Launay, J.; Dunbar, R.I. The ice-breaker effect: Singing mediates fast social bonding. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015, 2, 150221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.F.; Di Costa, S.; Beck, B.; Haggard, P. I just lost it! Fear and anger reduce the sense of agency: A study using intentional binding. Exp. Brain Res. 2019, 237, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWall, C.N.; Anderson, C.A.; Bushman, B.J. The general aggression model: Theoretical extensions to violence. Psychol. Viol. 2011, 1, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, L.; Zaenen, A. Contextual valence shifters. In Computing Attitude and Affect in Text: Theory and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, S.M. Obtaining Reliable Human Ratings of Valence, Arousal, and Dominance for 20,000 English Words. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 15–20 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens, P.; Tuerlinckx, F.; Yik, M.; Koval, P.; Coosemans, J.; Zeng, K.J.; Russell, J.A. The relation between valence and arousal in subjective experience varies with personality and culture. J. Pers. 2017, 85, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergallito, A.; Petilli, M.A.; Cattaneo, L.; Marelli, M. Somatic and visceral effects of word valence, arousal and concreteness in a continuum lexical space. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M.; Thelwall, S. Retweeting for COVID-19: Consensus building, information sharing, dissent, and lockdown life. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.02793. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, J.; Enria, D.; Giesecke, J.; Heymann, D.L.; Ihekweazu, C.; Kobinger, G.; Lane, H.C.; Memish, Z.; Oh, M.D.; Schuchat, A.; et al. COVID-19: Towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 1015–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency Rank | #italylockdown | #sciacalli | #iorestoacasa |

| 1 | iorestoacasa | Meloni | italylockdown |

| 2 | coronavirus | SanitaPubblica | coronavirus |

| 3 | COVID19 | Sciacalli | italystaystrong |

| 4 | Covid19 | Salvini | COVID19 |

| 5 | IoRestoACasa | coronavirus | iostoacasa |

| 6 | andratuttobene | emergenzaCoronavirus | ItaliaZonaRossa |

| 7 | restiamoacasa | ItaliaViva | restiamoacasa |

| 8 | grazieanomeditutti | Sciacalle | CoronaVirusitaly |

| 9 | Coronavirus | governo | Coronavirus |

| 10 | coronavirusitalia | COVID19 | Conte |

| 11 | andràtuttobene | Coronavirus | restaacasa |

| 12 | flashmob | terroristi | coranavirusit |

| 13 | covid19italia | irresponsabili | Covid19 |

| 14 | litaliachiamò | Lega | celafaremo |

| 15 | Iorestoacasa | Berlusconi | Italy |

| 16 | coronarvirusitalia | facciamorete | COVID19italia |

| 17 | iostoacasa | FreeJulianAssange | italiazonaprotetta |

| 18 | coranavirusitalia | Conte | pandemia |

| 19 | covid19 | CoronaVirus | coranavirusitalia |

| 20 | IORESTOACASA | coronavi | COVID2019 |

| Closeness Rank | #italylockdown | #sciacalli | #iorestoacasa |

| 1 | coronavirus | coronavirus | iostoacasa |

| 2 | COVID19 | COVID19 | coronavirus |

| 3 | ItaliaZonaRossa | Salvini | COVID19 |

| 4 | iorestoacasa | Lega | andratuttobene |

| 5 | Covid19 | iorestoacasa | Covid19 |

| 6 | Italia | Conte | restiamoacasa |

| 7 | italystaystrong | facciamorete | quarantena |

| 8 | Italy | Governo | COVID2019 |

| 9 | pandemia | COVID2019 | COVID19italia |

| 10 | COVID2019 | Meloni | iorestoincasa |

| 11 | coronavirusitalia | Covid19 | coronarvirusitalia |

| 12 | italiazonaprotetta | 6marzo | italia |

| 13 | restiamoacasa | coronvirusitalia | andràtuttobene |

| 14 | lockdown | mascherine | covid19italia |

| 15 | iostoacasa | zonarossa | pandemia |

| 16 | coronarvirusitalia | Salvinivergognati | coranavirusitalia |

| 17 | coranavirusitalia | Coronavirus | CoronaVirusitaly |

| 18 | CoronaVirusitaly | coranavirusitalia | covid19 |

| 19 | Conte | irresponsabili | Italia |

| 20 | COVID19italia | restiamoacasa | coronavirusitalIa |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stella, M.; Restocchi, V.; De Deyne, S. #lockdown: Network-Enhanced Emotional Profiling in the Time of COVID-19. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2020, 4, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc4020014

Stella M, Restocchi V, De Deyne S. #lockdown: Network-Enhanced Emotional Profiling in the Time of COVID-19. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2020; 4(2):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc4020014

Chicago/Turabian StyleStella, Massimo, Valerio Restocchi, and Simon De Deyne. 2020. "#lockdown: Network-Enhanced Emotional Profiling in the Time of COVID-19" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 4, no. 2: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc4020014

APA StyleStella, M., Restocchi, V., & De Deyne, S. (2020). #lockdown: Network-Enhanced Emotional Profiling in the Time of COVID-19. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 4(2), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc4020014