Big Data Analytics and AI for Consumer Behavior in Digital Marketing: Applications, Synthetic and Dark Data, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

Unique Contribution of This Review

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Consumer Behavior in Digital Marketing

2.2. Big Data and AI Capabilities in Marketing

2.3. Positioning Relative to Prior Reviews

3. Methods

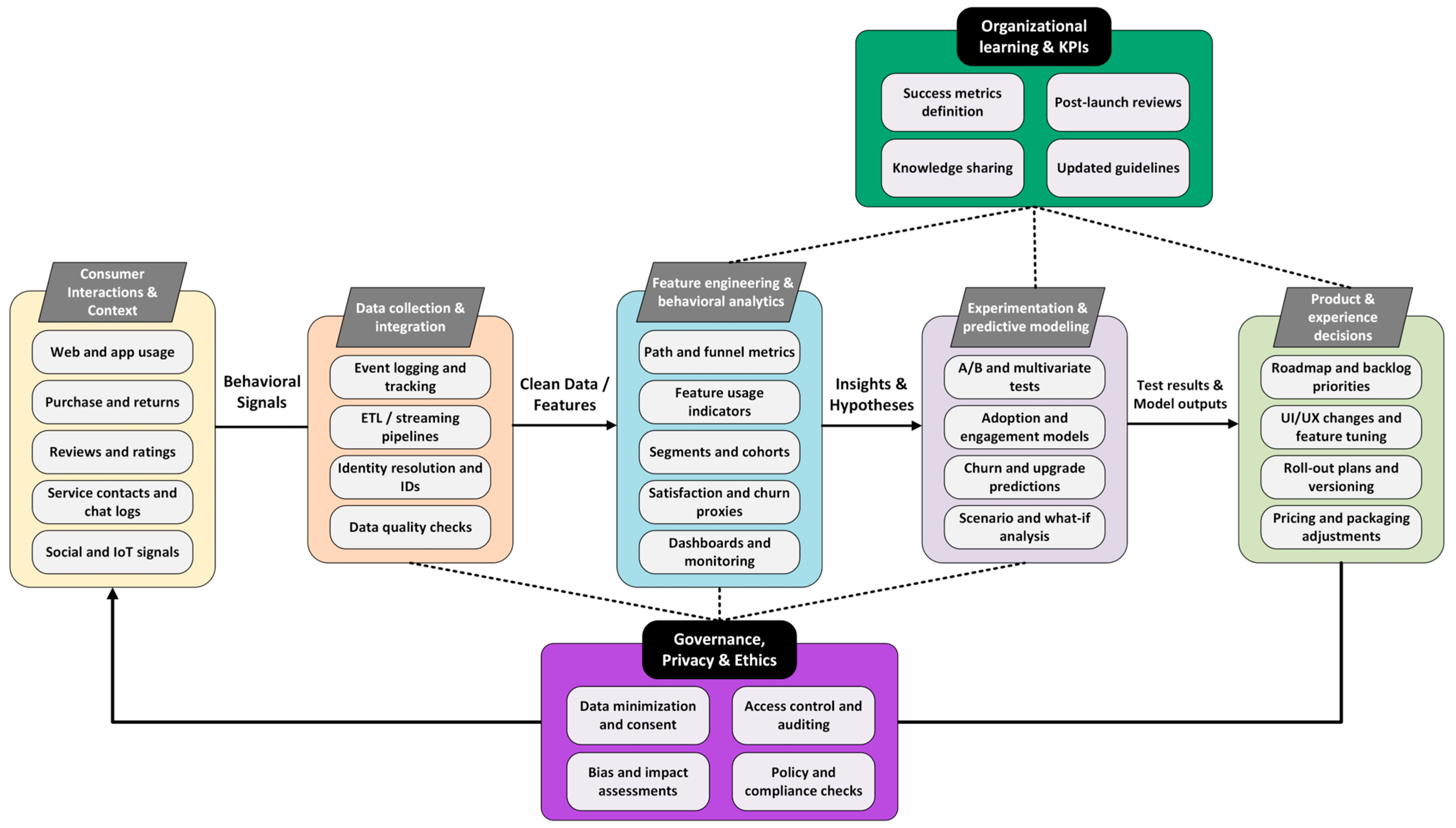

4. Applications of Big Data in Consumer Behavior Analysis

4.1. Personalized Marketing and Recommender Systems

4.1.1. Collaborative Filtering

4.1.2. Content-Based Filtering

4.1.3. Hybrid Methods

4.1.4. Advanced Predictive Modeling and Deep Learning

4.2. Dynamic Pricing Strategies

4.3. Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

4.4. Product Development and Innovation

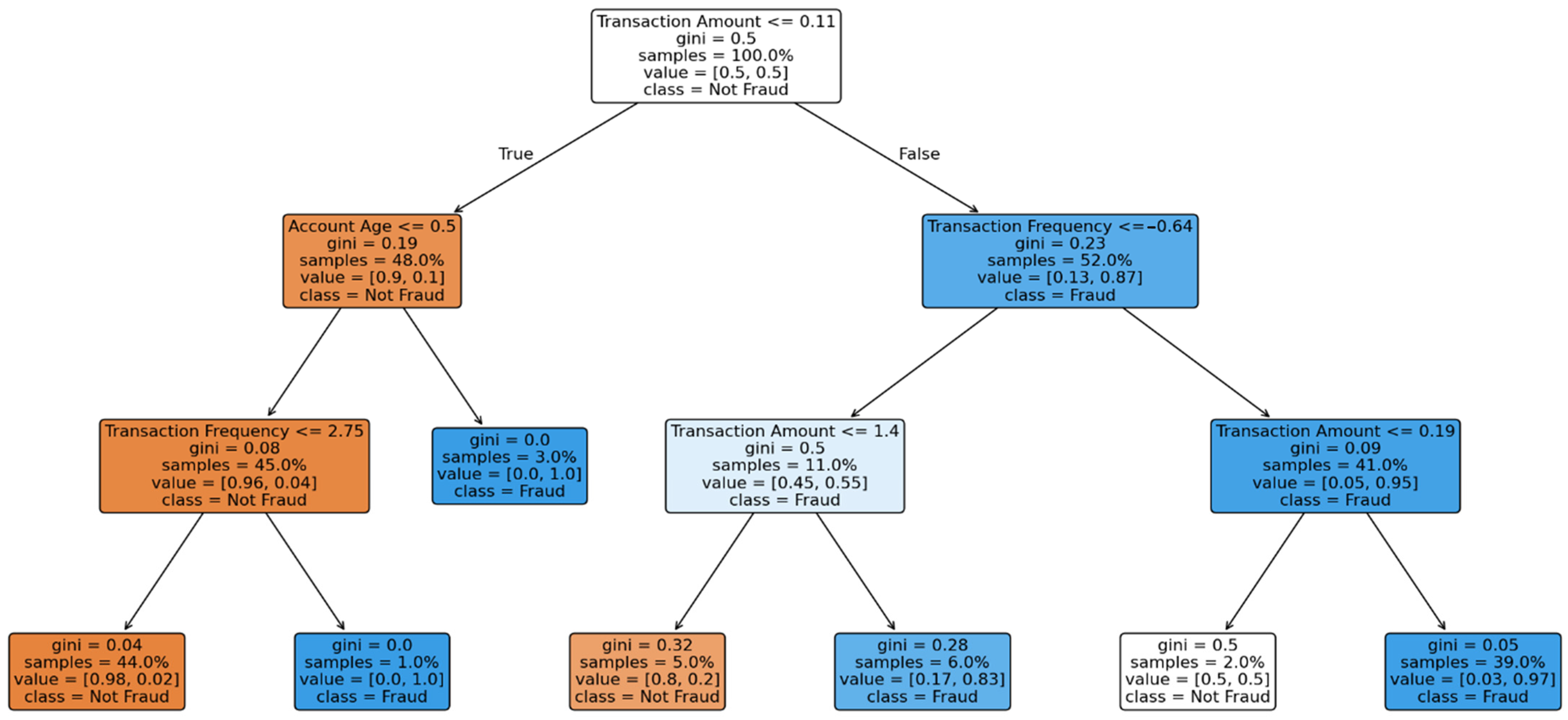

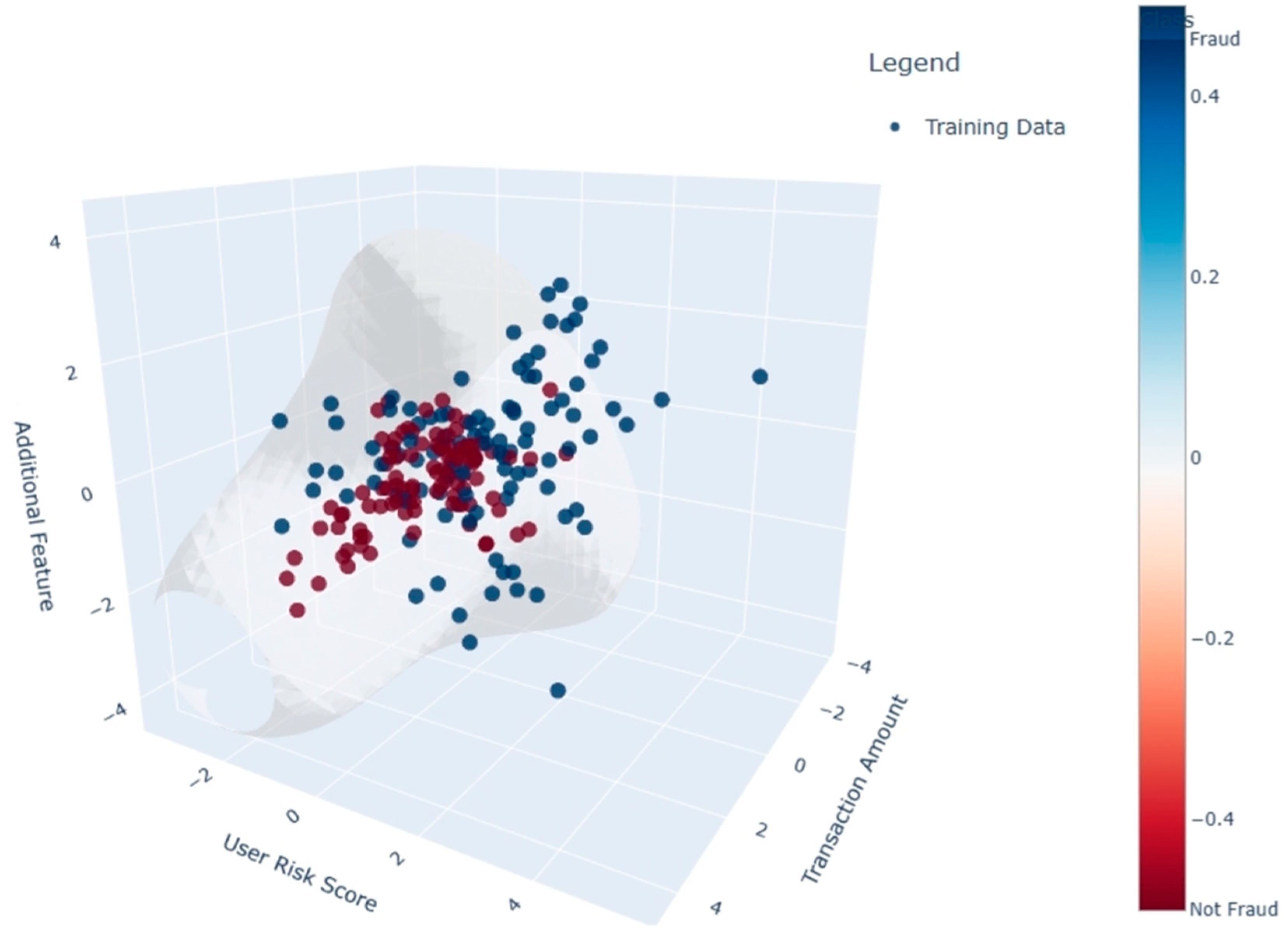

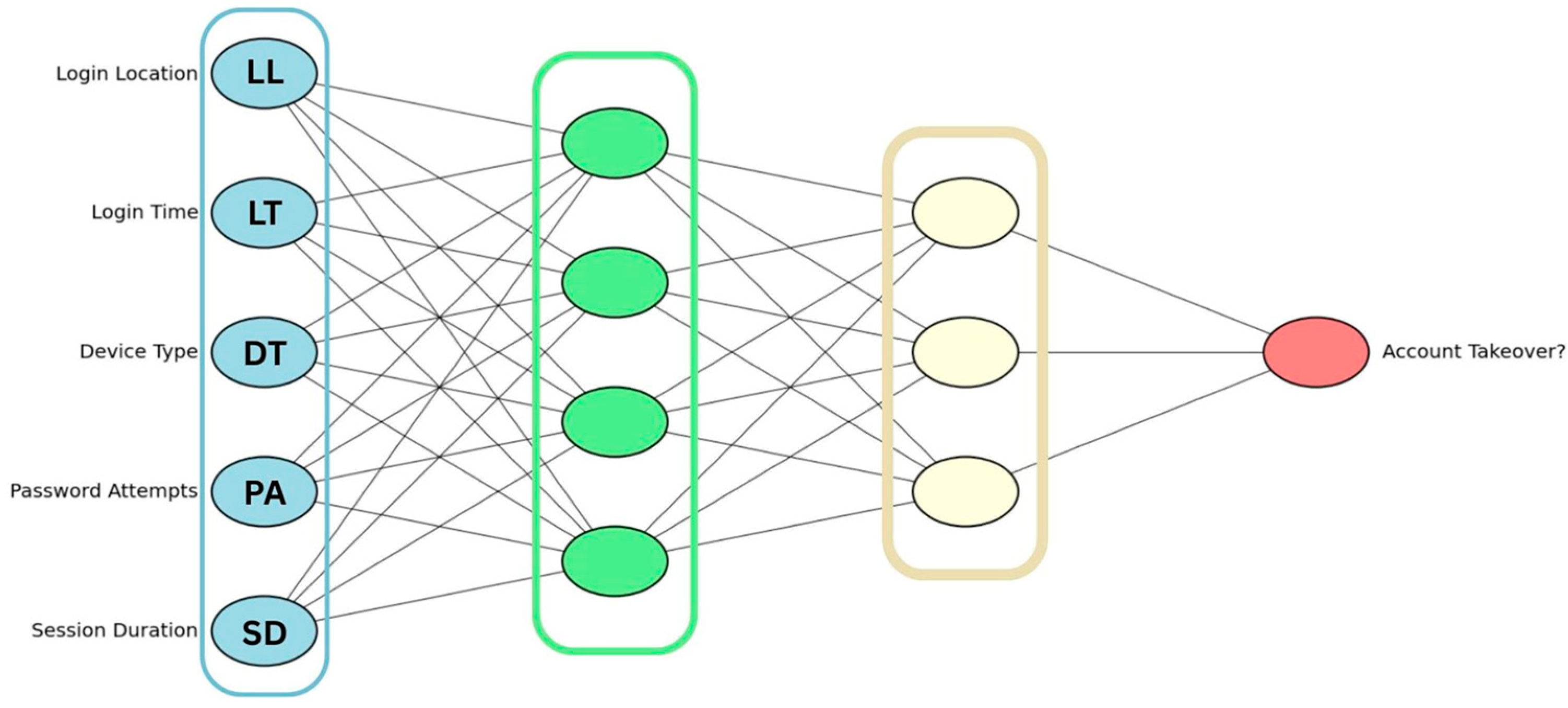

4.5. Fraud Detection and Prevention

- Isolation Forests isolate anomalies by recursively partitioning the feature space at random; fraudulent transactions, being rare and different, tend to be isolated in fewer steps [109].

- Autoencoders learn to reconstruct normal transaction patterns; large reconstruction errors indicate that an input deviates from what the network has seen during training [110].

- Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) model sequential spending behavior and can identify abrupt shifts in transaction sequences that may correspond to account takeover [111].

- Graph-based methods represent relationships among cards, accounts, merchants and devices as networks, highlighting suspicious subgraphs that correspond to coordinated fraud rings [112].

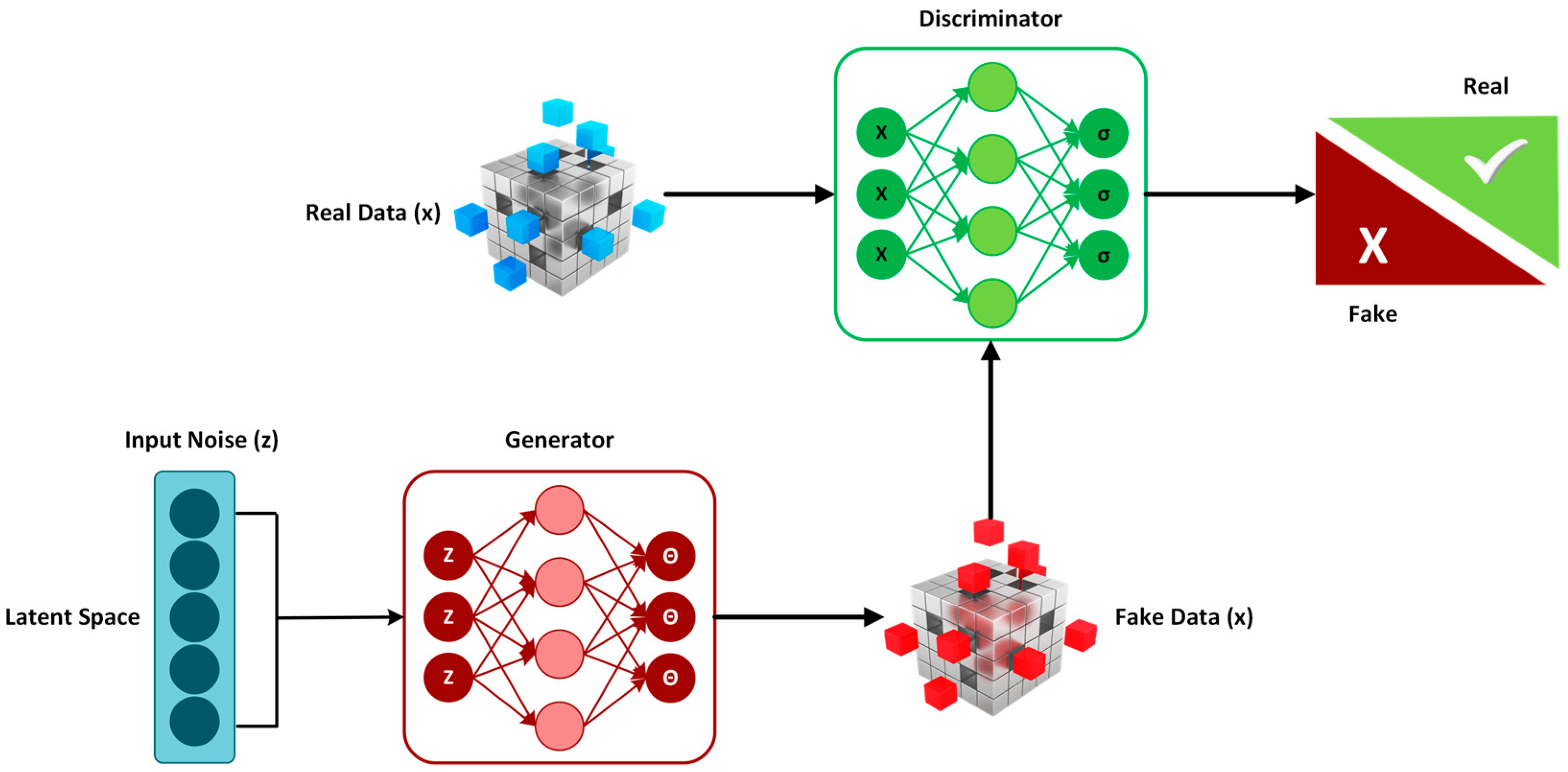

5. Synthetic Data and Its Role in Consumer Behavior Analysis

5.1. What Is Synthetic Data

5.2. Advantages of Synthetic Data in Consumer Analysis

5.3. Limitations and Challenges

6. Dark Data and Unused Consumer Insights

6.1. Definition and Types of Dark Data

6.2. Sources, Uses and Marketing Value

6.3. Challenges, Risks and Ethical Considerations

7. Discussion and Future Directions

7.1. Synthesis of Main Insights

7.2. Implications for Digital Marketing Practice

7.3. Research Implications and Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lamberton, C.; Stephen, A.T. A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing research’s evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future research. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweidel, D.A.; Bart, Y.; Inman, J.J.; Stephen, A.T.; Libai, B.; Andrews, M.; Babić Rosario, A.; Chae, I.; Chen, Z.; Kupor, D.; et al. How consumer digital signals are reshaping the customer journey. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 1257–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Fosso Wamba, S. Big data analytics in e-commerce: A systematic review and agenda for future research. Electron. Mark. 2016, 26, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R. Using data sciences in digital marketing: Framework, methods, and performance metrics. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.; Basu, A.; Batra, R. Marketing analytics: The bridge between customer data and strategic decisions. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 1796–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. How has data-driven marketing evolved: Challenges and opportunities with emerging technologies. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R.; Škare, V.; Dosen, D.O. Is AI-based digital marketing ethical? Assessing a new data privacy paradox. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, H.; Kashif, M. Artificial intelligence and predictive marketing: An ethical framework from managers’ perspective. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2025, 29, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaponis, A.; Maragoudakis, M.; Sofianos, K.C. Enhancing user experiences in digital marketing through machine learning: Cases, trends, and challenges. Computers 2025, 14, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riandhi, A.N.; Arviansyah, M.R.; Sondari, M.C. AI and consumer behavior: Trends, technologies, and future directions from a scopus-based systematic review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2544984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomotey, R.K.; Kumi, S.; Ray, M.; Deters, R. Synthetic data digital twins and data trusts control for privacy in health data sharing. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Workshop on Secure and Trustworthy Cyber-Physical Systems Porto, Porto, Portugal, 21 June 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenschink, P.; Reutterer, T.; Vamosi, S.; Vamosi, R.; Sun, C.; Kalcher, K. Deep generative models for synthetic data: A survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 47304–47320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaitan, O.F.; Adebanjo, T.A.; Obozokhai, L.I.; Iwerumoh, A.N.; Balogun, I.O.; Ojo, D.A. Dark data in business intelligence: A systematic review of challenges, opportunities, and value creation potential. J. Econ. Bus. Commer. 2025, 2, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridasan, A.C.; Fernando, A.G.; Saju, B. A systematic review of consumer information search in online and offline environments. RAUSP Manag. J. 2021, 56, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, R. The Coronavirus shopping anxiety scale: Initial validation and development. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 31, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-P.; Fan, W.-S.; Tsai, M.-C. Applying Stimulus–Organism–Response Theory to Explore the Effects of Augmented Reality on Consumer Purchase Intention for Teenage Fashion Hair Dyes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.; Kaye, S.A.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. What factors contribute to the acceptance of artificial intelligence? A systematic review. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 77, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Blazquez, V.; Oh, T. Determinants of generative AI system adoption and usage behavior in Korean companies: Applying the UTAUT model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X.; Wang, Y. The Impact of AI-Personalized Recommendations on Clicking Intentions: Evidence from Chinese E-Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Peterson, R.A.; Choi, J. Privacy concern and its consequences: A meta-analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 196, 122789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezer, M.; Dienlin, T.; Baruh, L. Getting the privacy calculus right: Analyzing the relations between privacy concerns, expected benefits, and self-disclosure using response surface analysis. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2022, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, J. The Effects of E-Commerce Recommendation System Transparency on Consumer Trust: Exploring Parallel Multiple Mediators and a Moderator. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2630–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, D.; Aivaz, K.-A.; Vancea, D.P.C.; Condrea, E.; Dragan, C.; Olteanu, A.C. Consumer Trust in AI Algorithms Used in E-Commerce: A Case Study of College Students at a Romanian Public University. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilino, L.; Di Dio, C.; Manzi, F.; Massaro, D.; Bisconti, P.; Marchetti, A. Decoding Trust in Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Measures and Related Variables. Informatics 2025, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, M.; Joudaki, M.; Beikmohammadi, A.; Arabnia, H.R. Customer Churn Prediction: A Systematic Review of Recent Advances, Trends, and Challenges in Machine Learning and Deep Learning. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2025, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnino, A.A.; Maruccia, Y.; Cavuoti, S.; Riccio, G.; Tutone, A.; Crupi, R.; Pagliaro, A. An Introduction to Machine Learning Methods for Fraud Detection. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mauro, A.; Sestino, A.; Bacconi, A. Machine learning and artificial intelligence use in marketing: A general taxonomy. Ital. J. Mark. 2022, 2022, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, E.; Rahman, M.; Ding, C.; Huang, J.X.; Raza, S. Based recommender systems: A survey of approaches, challenges and future perspectives. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 58, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, A.; Vaz, B. Survey on Synthetic Data Generation, Evaluation Methods and GANs. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, N.; Rocha, A.D.; Barata, J. Data management in industry: Concepts, systematic review and future directions. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, L.B.; Krishnamoorthy, A.; Yadav, S.; Dixon, H.E.T. Scrolling Into Choice: The Psychology and Practice of Social Media Consumerism. Adv. Consum. Res. 2025, 2, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.H.; Sultana, S.; Hossain, M.M.; Islam, S.M.A. The Impact of Digital Marketing Strategies on Consumer Behavior: A Comprehensive Review. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2025, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariguna, T.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Assessing the impact of artificial intelligence on customer performance: A quantitative study using partial least squares methodology. Data Sci. Manag. 2024, 7, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakradhar, B.S.; Vijey, M.; Tunk, S. Synthetic Data Generation for Marketing Insights. In Predictive Analytics and Generative AI for Data-Driven Marketing Strategies; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Abingdon, UK, 2024; pp. 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jae, Y.I.; Hwa, P.I. Personalized Digital Marketing Strategies: A Data-Driven Approach Using Marketing Analytics. J. Manag. Inform. 2025, 4, 668–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, L.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Klavdianos, C. Interactive Viral Marketing Through Big Data Analytics, Influencer Networks, AI Integration, and Ethical Dimensions. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Verma, S.; Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Personalization in personalized marketing: Trends and ways forward. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1529–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, O.; Karjaluoto, H.; Saarijärvi, H. Personalization and hedonic motivation in creating customer experiences and loyalty in omnichannel retail. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraj, D.; Vuković, M.; Hotovec, P. A Survey on User Profiling, Data Collection, and Privacy Issues of Internet Services. Telecom 2024, 5, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusov, M.; Ma, L.; Jamal, Z. Crumbs of the cookie: User profiling in customer-base analysis and behavioral targeting. Mark. Sci. 2016, 35, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagtani, H.; Jhawar, M.G.; Gupta, A.; Mehrotra, R. Quantifying and leveraging user fatigue for interventions in recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’23), Taipei, China, 23–27 July 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yusof, Y. Emerging trends in real-time recommendation systems: A deep dive into multi-behavior streaming processing and recommendation for e-commerce platforms. J. Internet Serv. Inf. Secur. 2024, 14, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xiong, F.; Chen, H. A Comprehensive Survey of Recommender Systems Based on Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, A.; El Adrousy, W.; Sarhan, S.; Elmougy, S. A deep learning based hybrid recommendation model for internet users. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srifi, M.; Oussous, A.; Ait Lahcen, A.; Mouline, S. Recommender Systems Based on Collaborative Filtering Using Review Texts—A Survey. Information 2020, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Tian, H.; Wu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Feng, T. A new item-based collaborative filtering algorithm to improve the accuracy of prediction in sparse data. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2022, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, H.I.; Amer, A.A.; Amer, Y.A.; Nguyen, L.; Al-Maqaleh, B. Boosting the item-based collaborative filtering model with novel similarity measures. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2023, 16, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, G.; Sathiya Devi, S. Hybrid recommendation system based on collaborative and content-based filtering. Cybern. Syst. 2023, 54, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumintu, I. Content-Based Recommendation Engine Using Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency Vectorization and Cosine Similarity: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 18–20 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J. A survey of long-tail item recommendation methods. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 7536316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çano, E.; Morisio, M. Hybrid recommender systems: A systematic literature review. Intell. Data Anal. 2017, 21, 1487–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widayanti, R.; Chakim, M.H.R.; Lukita, C.; Rahardja, U.; Lutfiani, N. Improving recommender systems using hybrid techniques of collaborative filtering and content-based filtering. J. Appl. Data Sci. 2023, 4, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheewala, S.; Xu, S.; Yeom, S. In-depth survey: Deep learning in recommender systems—Exploring prediction and ranking models, datasets, feature analysis, and emerging trends. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 10875–10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liao, L.; Zhang, H.; Nie, L.; Hu, X.; Chua, T.-S. Neural collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW ’17), Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayemowa, M.O.; Ibrahim, R.; Bena, Y.A. A systematic review of the literature on deep learning approaches for cross-domain recommender systems. Data Anal. 2024, 4, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkers, T.; Loepp, B.; Ziegler, J. Sequential user-based recurrent neural network recommendations. In Proceedings of the RecSys ‘17 11th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Como, Italy, 27–31 August 2017; pp. 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lim, H.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Kim, S.; Kim, J. Enhancing Review-Based Recommendations Through Local and Global Feature Fusion. Electronics 2025, 14, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonicalzi, S.; De Caro, M.; Giovanola, B. Artificial intelligence and autonomy: On the ethical dimension of recommender systems. Topoi 2023, 42, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Pawłowska-Nowak, M. Dynamic Pricing Method in the E-Commerce Industry Using Machine Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, E.; Van Hentenryck, P. Real-time pricing optimization for ride-hailing quality of service. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-21), Virtual, 19–26 August 2021; Zhou, Z.-H., Ed.; International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021; pp. 3742–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battifarano, M.; Qian, Z.S. Predicting real-time surge pricing of ride-sourcing companies. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 107, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Zhu, H.; Korolko, N.; Woodard, D. Dynamic pricing and matching in ride-hailing platforms. Nav. Res. Logist. 2020, 67, 705–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, G.Y.; Keskin, N.B. Personalized dynamic pricing with machine learning: High-dimensional features and heterogeneous elasticity. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 5549–5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yang, Y.; Fu, S. Deep reinforcement learning approach for solving joint pricing and inventory problem with reference price effects. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 195, 116564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M. A systematic literature review of dynamic pricing strategies. Int. Bus. Res. 2022, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, L.; Theodoropoulou, A. Leveraging big data analytics for understanding consumer behavior in digital marketing: A systematic review. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 2024, 3641502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vomberg, A.; Homburg, C.; Sarantopoulos, P. Algorithmic pricing: Effects on consumer trust and price search. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2024, 42, 1166–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidhani, Y.; Venkata Naga Ramesh, J.; Singh, S.; Dagar, R.; Rao, T.S.M.; Godla, S.R.; El-Ebiary, Y.A.B. AI-driven predictive analytics for CRM to enhance retention, personalization and decision-making. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2025, 16, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.S.; Viloria Garcia, A.; Lim, Y.-W. A data-driven approach to customer lifetime value prediction using probability and machine learning models. Decis. Anal. J. 2025, 16, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Mele, G.; Siachou, E.; Schito, G. A structured literature review on Big Data for customer relationship management (CRM): Toward a future agenda in international marketing. Int. Mark. Rev. 2022, 39, 1069–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-Y.; Chen, C.-C. Driving Innovation Through Customer Relationship Management—A Data-Driven Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, A.O.; Kolade, O.; Onifade, O.F. Customer retention model using machine learning for improved user-centric quality of experience through personalised quality of service. J. Bus. Anal. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.S.; Siam, M.A.; Ahad, M.A.; Hossain, M.N.; Ridoy, M.H.; Rabbi, M.N.S.; Hossain, A.; Jakir, T. Predictive Analytics for Customer Retention: Machine Learning Models to Analyze and Mitigate Churn in E-Commerce Platforms. J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2024, 6, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnofeli, K.K.; Akter, S.; Yanamandram, V.; Hani, U. AI-powered CRM capability model: Advancing marketing ambidexterity, profitability and competitive performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2026, 86, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhang, L. Revolutionizing market surveillance: Customer relationship management with machine learning. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. Predictive customer intelligence: A synthetic data-driven evaluation of machine learning and NLP integration for CRM churn prediction and lifetime value forecasting. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2025, 187, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, K.; Vorster, L.; Brown, D.M. Understanding customer responses to AI-driven personalized journeys: Impacts on the customer experience. J. Advert. 2025, 54, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, T.; Montagna, F.; Cascini, G.; Cantamessa, M. Data-driven innovation: Challenges and insights of engineering design. Des. Sci. 2025, 11, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrabadi, M.A.; Beauregard, Y.; Ekhlassi, A. The implication of user-generated content in new product development process: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, H. Data-driven analysis of usage-feature interactions for new product design. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 296, 128932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakoulopoulos, A.; Pergantis, M.; Lamprogeorgos, A. User Experience, Functionality and Aesthetics Evaluation in an Academic Multi-Site Web Ecosystem. Future Internet 2024, 16, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalauskas, V.; Kriksciuniene, D. Personalized Advertising in E-Commerce: Using Clickstream Data to Target High-Value Customers. Algorithms 2024, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quin, F.; Weyns, D.; Galster, M.; Silva, C.C. A/B testing: A systematic literature review. J. Syst. Softw. 2024, 211, 112011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, M.; Gregurec, I.; Vujović, U. Measuring the Effectiveness of Online Sales by Conducting A/B Testing. Market-Tržište 2023, 35, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaketheep, K.; Al-Ahmed, H.; Mansour, A. Beyond purchase patterns: Harnessing predictive analytics to anticipate unarticulated consumer needs. Acta Psychol. 2025, 242, 105089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, R. Necessary condition analysis for sales funnel optimization. J. Mark. Anal. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerril-Castrillejo, I.; Nieto-García, M.; Muñoz-Gallego, P.A. Do satisfaction and satiation both drive immediate and delayed subscription cancellation? Implications for subscription video-on-demand services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2026, 89, 104624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, P.B.; Perestrelo, B.M.; Santos, J.D. Measuring Customer Experience in E-Retail. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, N.; Biega, A.J. (Re) Politicizing digital well-being: Beyond user engagements. In Proceedings of the CHI ’22: 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 30 April–6 May 2022; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Thoben, K.-D. A Systematic Procedure for Utilization of Product Usage Information in Product Development. Information 2022, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Li, S.; Zeng, C.; Wei, H.; Hu, J. Big Data and AI-Driven Product Design: A Survey. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanini, P.; Rossi, S.; Zvizdic, E.; Domenig, T. Online payment fraud: From anomaly detection to risk management. Financ. Innov. 2023, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Aros, L.; Bustamante Molano, L.X.; Gutierrez-Portela, F.; Moreno Hernandez, J.J.; Rodríguez Barrero, M.S. Financial fraud detection through the application of machine learning techniques: A literature review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, W.; Gadsden, S.A.; Yawney, J. Financial fraud: A review of anomaly detection techniques and recent advances. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 193, 116429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.; Uchida, S. A comparative evaluation of unsupervised anomaly detection algorithms for multivariate data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, A.; Rao, A.C.S. An outlier detection algorithm based on KNN-kernel density estimation. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Vinces, B.V.; Schubert, E.; Zimek, A.; Cordeiro, R.L. A comparative evaluation of clustering-based outlier detection. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 39, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Vasarhelyi, M. Anomaly detection with the density based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) to detect potentially fraudulent wire transfers. Int. J. Digit. Account. Res. 2024, 24, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarfaj, F.K.; Malik, I.; Khan, H.U.; Almusallam, N.; Ramzan, M.; Ahmed, M. Credit card fraud detection using state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 39700–39715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, A.O.; Akinyelu, A.A. A survey of machine-learning and nature-inspired based credit card fraud detection techniques. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2017, 8, 937–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornadula, V.N.; Geetha, S. Credit card fraud detection using machine learning algorithms. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 165, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcillo, F.; Dal Pozzolo, A.; Le Borgne, Y.A.; Caelen, O.; Mazzer, Y.; Bontempi, G. Scarff: A scalable framework for streaming credit card fraud detection with spark. Inf. Fusion 2018, 41, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeyale, K.M.; Moruff, O.A.; Taofeekat, S.I.T.; Kayode, S.M. A support vector machine credit card fraud detection model based on high imbalance dataset. J. Comput. Soc. 2024, 5, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanai, H.; Abbasimehr, H. A novel combined approach based on deep autoencoder and deep classifiers for credit card fraud detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 217, 119562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forough, J.; Momtazi, S. Ensemble of deep sequential models for credit card fraud detection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 99, 106883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, A.; Donnarumma, F.; Isgrò, F.; Prevete, R. A survey on modern trainable activation functions. Neural Netw. 2021, 138, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, S.R.; Gongada, T.N.; Santosh, K.; Chowdhary, H.; Sabareesh, R.; Muthuperumal, S. Financial fraud detection using hybrid convolutional and recurrent neural networks: An analysis of unstructured data in banking. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), Melmaruvathur, India, 25–27 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xiang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ting, K.M. Anomaly detection based on isolation mechanisms: A survey. Mach. Intell. Res. 2025, 22, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Thakur, S.; Ghosh, M.; Saha, S.K. An autoencoder based model for detecting fraudulent credit card transaction. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 167, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundile, O.; Babalola, O.; Ogunbanwo, A.; Ogundile, O.; Balyan, V. Credit Card Fraud: Analysis of Feature Extraction Techniques for Ensemble Hidden Markov Model Prediction Approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Zou, Y.; Xiang, S.; Jiang, C. Graph neural networks for financial fraud detection: A review. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 19, 199609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immadisetty, A. Real-Time Fraud Detection Using Streaming Data in Financial Transactions. J. Recent Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. (JRTCSE) 2025, 13, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.R.B.; Kanagala, P.; Ravichandran, P.; Pulimamidi, R.; Sivarambabu, P.V.; Polireddi, N.S.A. Effective fraud detection in e-commerce: Leveraging machine learning and big data analytics. Meas. Sens. 2024, 33, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latah, M. Detection of malicious social bots: A survey and a refined taxonomy. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 151, 113383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Moghaddam, V.; Anwar, A. Data-Driven Behavioural Biometrics for Continuous and Adaptive User Verification Using Smartphone and Smartwatch. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A. Security perception in the adoption of mobile payment and the moderating effect of gender. PSU Res. Rev. 2019, 3, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyev, I.; Krivitskaya, A. Reducing false positives in bank anti-fraud systems based on rule induction in distributed tree-based models. Comput. Secur. 2022, 120, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Tsiotsou, R.; Sarfraz, M.; Ishaq, M.I. Trust recovery tactics in financial services: The moderating role of service failure severity. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023, 41, 1611–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luximon, Y.; Song, Y. The Role of Consumers’ Perceived Security, Perceived Control, Interface Design Features, and Conscientiousness in Continuous Use of Mobile Payment Services. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickley, S.J.; Chan, H.F.; Dao, B.; Torgler, B.; Tran, S.; Zimbatu, A. Comparing human and synthetic data in service research: Using augmented language models to study service failures and recoveries. J. Serv. Mark. 2025, 39, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochon, D.; Schwartz, J. The importance of construct validity in consumer research. J. Consum. Psychol. 2020, 30, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Mahmoud, Q.H. A Systematic Review of Synthetic Data Generation Techniques Using Generative AI. Electronics 2024, 13, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, W.; Stummer, C. Agent-based modeling of new product market diffusion: An overview of strengths and criticisms. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 305, 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.; Lee, W.; Kim, D.-S.; Shin, H. Copula-based approach to synthetic population generation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Loignon, A.C.; Shrestha, S.; Banks, G.C.; Oswald, F.L. Advancing organizational science through synthetic data: A path to enhanced data sharing and collaboration. J. Bus. Psychol. 2025, 40, 771–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suguna, R.; Suriya Prakash, J.; Aditya Pai, H.; Mahesh, T.R.; Vinoth Kumar, V.; Yimer, T.E. Mitigating class imbalance in churn prediction with ensemble methods and SMOTE. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, S.; Dervovic, D.; Mahfouz, M.; Tillman, R.; Reddy, P.; Veloso, M. Generating synthetic data in finance: Opportunities, challenges and pitfalls. In Proceedings of the First ACM International Conference on AI in Finance (AIFin ’20), New York, NY, USA, 15–16 October 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, M.D.; Chaney, A.; Castells, P.; Burke, R.; Rohde, D.; Slokom, M. Simurec: Workshop on synthetic data and simulation methods for recommender systems research. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 803–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slokom, M. Comparing recommender systems using synthetic data. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 27 September 2018; pp. 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeinia, S.M.; Rahmani, R. Recommender system based on customer segmentation (RSCS). Kybernetes 2016, 45, 946–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patki, N.; Wedge, R.; Veeramachaneni, K. The synthetic data vault. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 17–19 October 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyllie, S.; Shumailov, I.; Papernot, N. Fairness feedback loops: Training on synthetic data amplifies bias. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’24), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–6 June 2024; pp. 2113–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbierato, E.; Vedova, M.L.D.; Tessera, D.; Toti, D.; Vanoli, N. A Methodology for Controlling Bias and Fairness in Synthetic Data Generation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, E.; Ohn, J.H.; Jo, H.; Park, M.J.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, C.M.; Ahn, S. Evaluating the utility of data integration with synthetic data and statistical matching. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willman-Iivarinen, H. The future of consumer decision making. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2017, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zherdeva, L.; Zherdev, D.; Nikonorov, A. Prediction of human behavior with synthetic data. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Information Technology and Nanotechnology (ITNT), Samara, Russia, 20–24 September 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyrup, T.; Lautrup, A.D.; Zimek, A.; Schneider-Kamp, P. Sharing is CAIRing: Characterizing principles and assessing properties of universal privacy evaluation for synthetic tabular data. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2024, 18, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beduschi, A. Synthetic data protection: Towards a paradigm change in data regulation? Big Data Soc. 2024, 11, 20539517241231277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Alojail, M. A Novel Approach for Deciphering Big Data Value Using Dark Data. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2022, 33, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marumolwa, L.; Marnewick, C. Unveiling Dark Data in Organisations: Sources, Challenges, and Mitigation Strategies. Int. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. Eng. Technol. (IJSSMET) 2025, 16, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A.; Crespino, A.M.; Del Vecchio, V.; Lazoi, M.; Marra, M. Understanding and defining dark data for the manufacturing industry. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimpel, G. Bringing dark data into the light: Illuminating existing IoT data lost within your organization. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.I.; Kwon, M.M. Dark data: Why What You Don’t Know Matters: Dark Data: Why What You Don’t Know Matters, by David J. Hand, New Jersey, US, Princeton University Press, 2020, 330 pp. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2023, 25, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schembera, B.; Durán, J.M. Dark data as the new challenge for big data science and the introduction of the scientific data officer. Philos. Technol. 2020, 33, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurn, S.; Kim, W. Improving Text Classification of Imbalanced Call Center Conversations Through Data Cleansing, Augmentation, and NER Metadata. Electronics 2025, 14, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfian, G.; Octava, M.Q.H.; Hilmy, F.M.; Nurhaliza, R.A.; Saputra, Y.M.; Putri, D.G.P.; Syahrian, F.; Fitriyani, N.L.; Atmaji, F.T.D.; Farooq, U.; et al. Customer Shopping Behavior Analysis Using RFID and Machine Learning Models. Information 2023, 14, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Dong, T.; Zhou, P.; Li, D.; Li, H. Leveraging Text Mining Techniques for Civil Aviation Service Improvement: Research on Key Topics and Association Rules of Passenger Complaints. Systems 2025, 13, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimpel, G. Dark data: The invisible resource that can drive performance now. J. Bus. Strategy 2021, 42, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.D.; Borah, A.; Palmatier, R.W. Data privacy: Effects on customer and firm performance. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Gebauer, H. Clean Customer Master Data for Customer Analytics: A Neglected Element of Data Monetization. Digital 2024, 4, 1020–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakic, D.; Stefanovic, D.; Vuckovic, T.; Zizakov, M.; Stevanov, B. Event Log Data Quality Issues and Solutions. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reviglio, U. The untamed and discreet role of data brokers in surveillance capitalism: A transnational and interdisciplinary overview. Internet Policy Rev. 2022, 11, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, L.; Cocq, C.; Gelfgren, S.; Enbom, J. Everyday Life in the Culture of Surveillance; Nordicom: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Lepore, C.; Eynard, J.; Laborde, R. From theory to practice: Data minimisation and technical review of verifiable credentials under the GDPR. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2025, 57, 106138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, A.; Münster, J. Detecting coverage bias in user-generated content. J. Media Econ. 2019, 32, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Lo, L.Y.H.; Xia, M.; Chen, Z.; Ma, X. Bias-aware design for informed decisions: Raising awareness of self-selection bias in user ratings and reviews. In Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 6(CSCW2), Taipei, China, 8–22 November 2022; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olteanu, A.; Castillo, C.; Diaz, F.; Kıcıman, E. Social data: Biases, methodological pitfalls, and ethical boundaries. Front. Big Data 2019, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finck, M.; Biega, A.J. Reviving purpose limitation and data minimisation in data-driven systems. Technol. Regul. 2021, 2021, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chereja, I.; Erdei, R.; Delinschi, D.; Pasca, E.; Avram, A.; Matei, O. Privacy-Conducive Data Ecosystem Architecture: By-Design Vulnerability Assessment Using Privacy Risk Expansion Factor and Privacy Exposure Index. Sensors 2025, 25, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, V.; von Grafenstein, M. Clarifying “personal data” and the role of anonymisation in data protection law: Including and excluding data from the scope of the GDPR (more clearly) through refining the concept of data protection. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2024, 52, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Advantage | Short Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy and data sharing | Shares structure of customer base without real identities | Bank sharing synthetic cards data with a vendor |

| Handling rare events | Adds extra samples for infrequent but important behaviors | Extra churn or fraud cases to train classifiers |

| Scenario analysis and stress tests | Simulates “what-if” market or policy conditions | New pricing rules or tighter credit criteria |

| Cheaper experimentation | Supports early testing when large A/B tests are not feasible | Comparing targeting rules before live rollout |

| Prototyping and education | Lets teams build pipelines without touching production data | Training analysts on a synthetic clickstream set |

| Reproducible research | Enables public datasets that mimic proprietary ones | Benchmarking recommender algorithms across studies |

| Dark Data Source | Typical Examples | Potential Marketing Value | Key Risks/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Customer service text | Emails, chat logs, complaint forms | Detect pain points, reasons for churn, UX issues | Sensitive content, re-identification |

| Call-center recordings | Audio from support and sales calls | Voice tone analysis, script testing, objection data | Heavy anonymization, storage costs |

| Web and app technical logs | Server logs, error logs, scroll events | Journey reconstruction, friction detection | Volume, noisy events, short retention |

| Social media and community posts | Comments, reviews, direct messages | Sentiment, themes, peer influence signals | Blurred consent, platform policies |

| In-store sensor and video data | Footfall sensors, camera feeds, beacons | Path analysis, zone heatmaps, display effectiveness | Strong privacy constraints, regulation |

| Legacy CRM and campaign files | Old databases, archived lists | Longitudinal views, cohort histories | Poor documentation, format issues |

| Future Direction | Short Description |

|---|---|

| Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning | Broader use of advanced models to personalize decisions and automate analytics. |

| Rise of Edge Computing | Moving parts of analytics to devices and stores for faster, local decisions. |

| Enhanced Consumer Participation | Giving users more control, insight and benefits from the data they share. |

| Development of Ethical Frameworks | Establishing clear rules for profiling, targeting and automated interventions. |

| Quantum Computing and Big Data Analytics | Testing quantum methods for complex optimization and pattern discovery tasks. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Theodorakopoulos, L.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Klavdianos, C. Big Data Analytics and AI for Consumer Behavior in Digital Marketing: Applications, Synthetic and Dark Data, and Future Directions. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2026, 10, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10020046

Theodorakopoulos L, Theodoropoulou A, Klavdianos C. Big Data Analytics and AI for Consumer Behavior in Digital Marketing: Applications, Synthetic and Dark Data, and Future Directions. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2026; 10(2):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10020046

Chicago/Turabian StyleTheodorakopoulos, Leonidas, Alexandra Theodoropoulou, and Christos Klavdianos. 2026. "Big Data Analytics and AI for Consumer Behavior in Digital Marketing: Applications, Synthetic and Dark Data, and Future Directions" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 10, no. 2: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10020046

APA StyleTheodorakopoulos, L., Theodoropoulou, A., & Klavdianos, C. (2026). Big Data Analytics and AI for Consumer Behavior in Digital Marketing: Applications, Synthetic and Dark Data, and Future Directions. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 10(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10020046