Lithology Identification from Well Logs via Meta-Information Tensors and Quality-Aware Weighting

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A Robust Feature Engineering (RFE) framework

- (2)

- A quality-aware XGBoost classification model

- (3)

- Systematic robustness evaluation

2. Materials and Methods

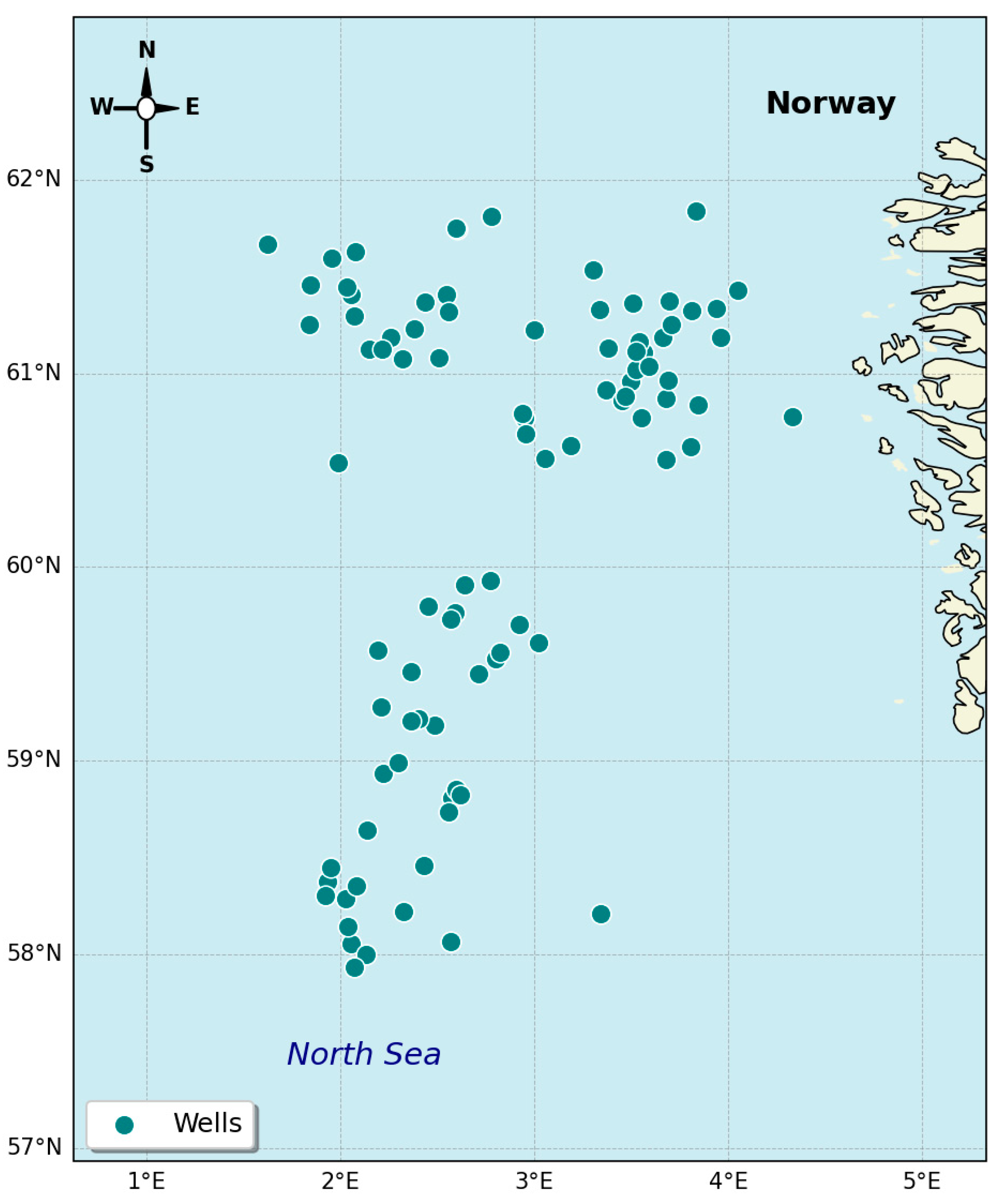

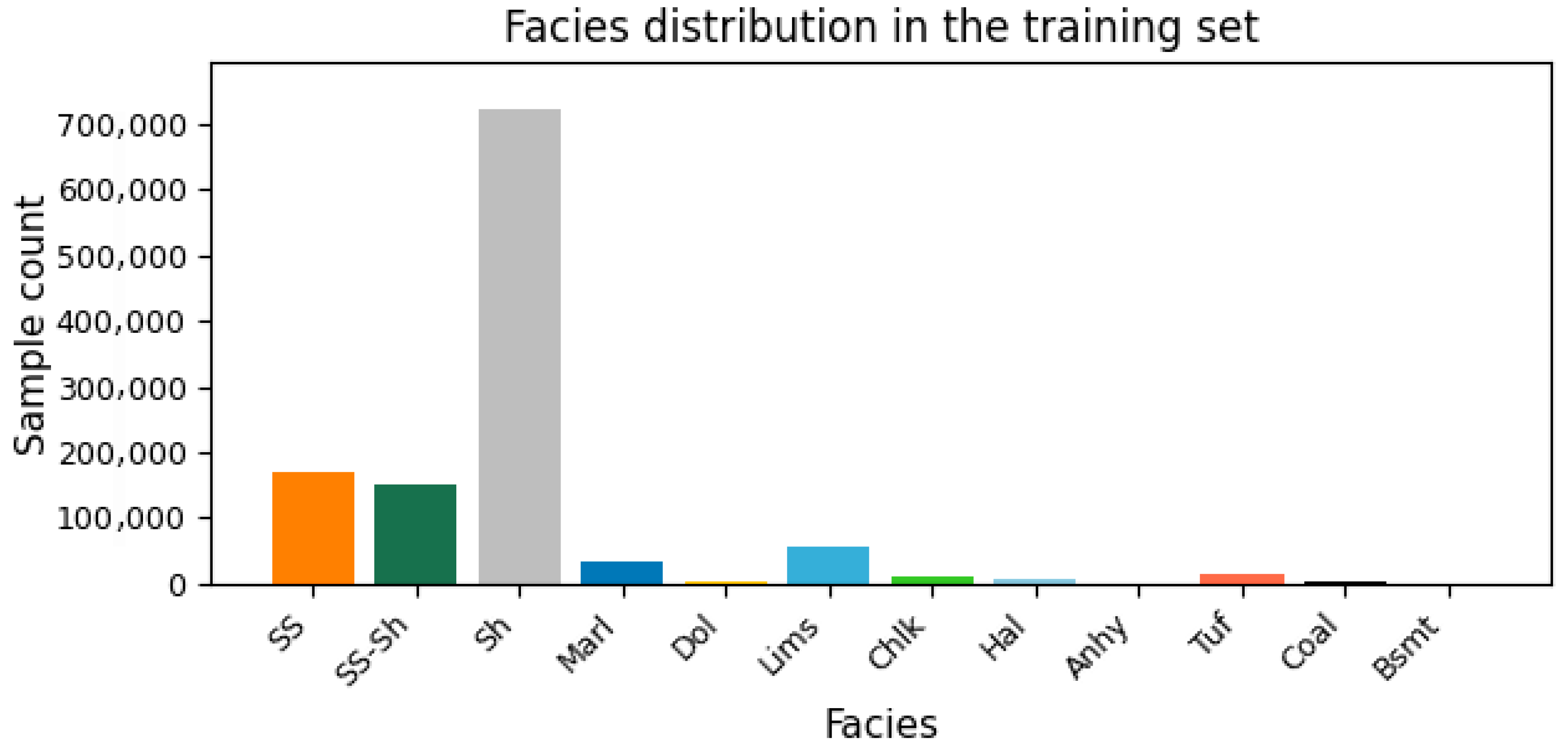

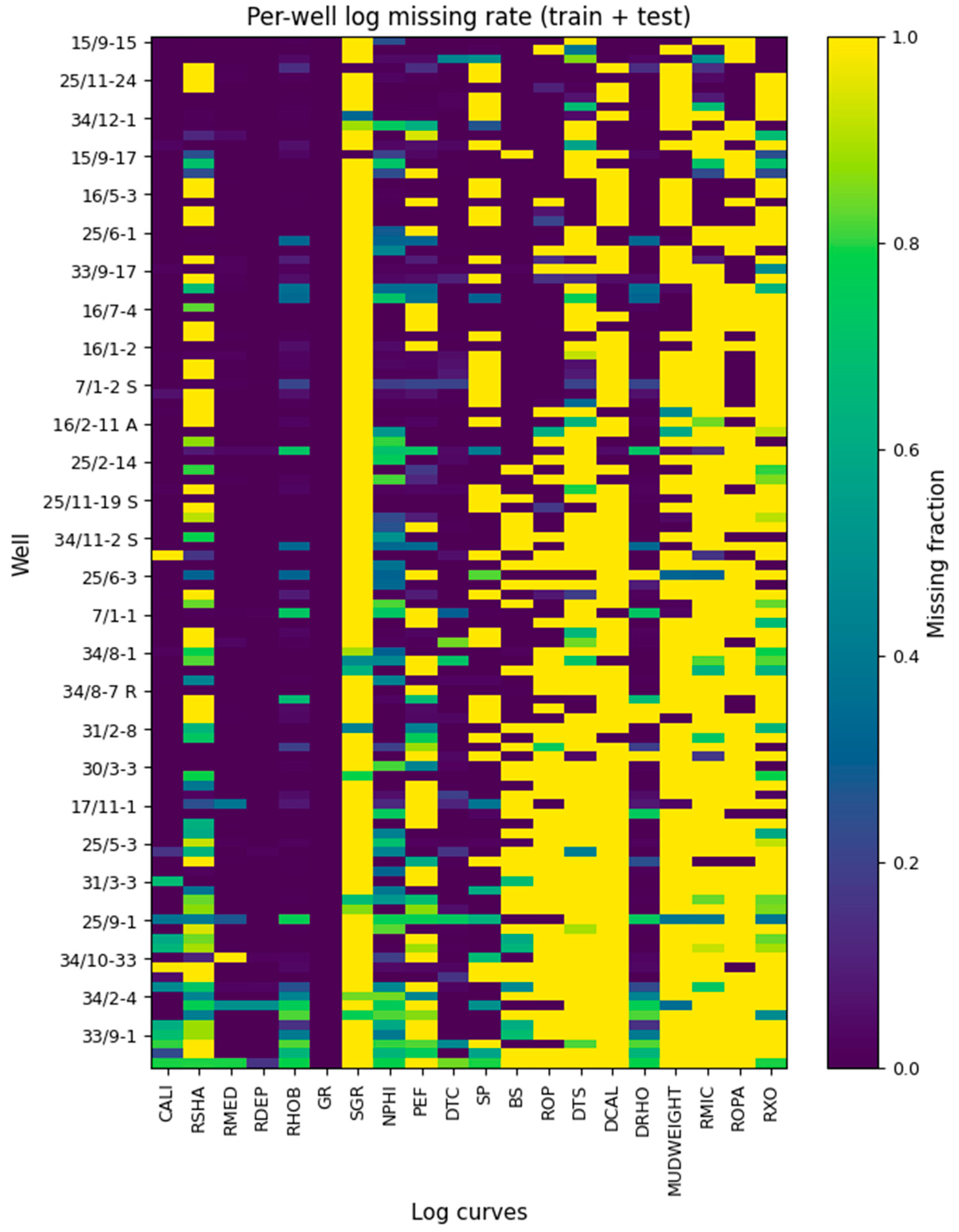

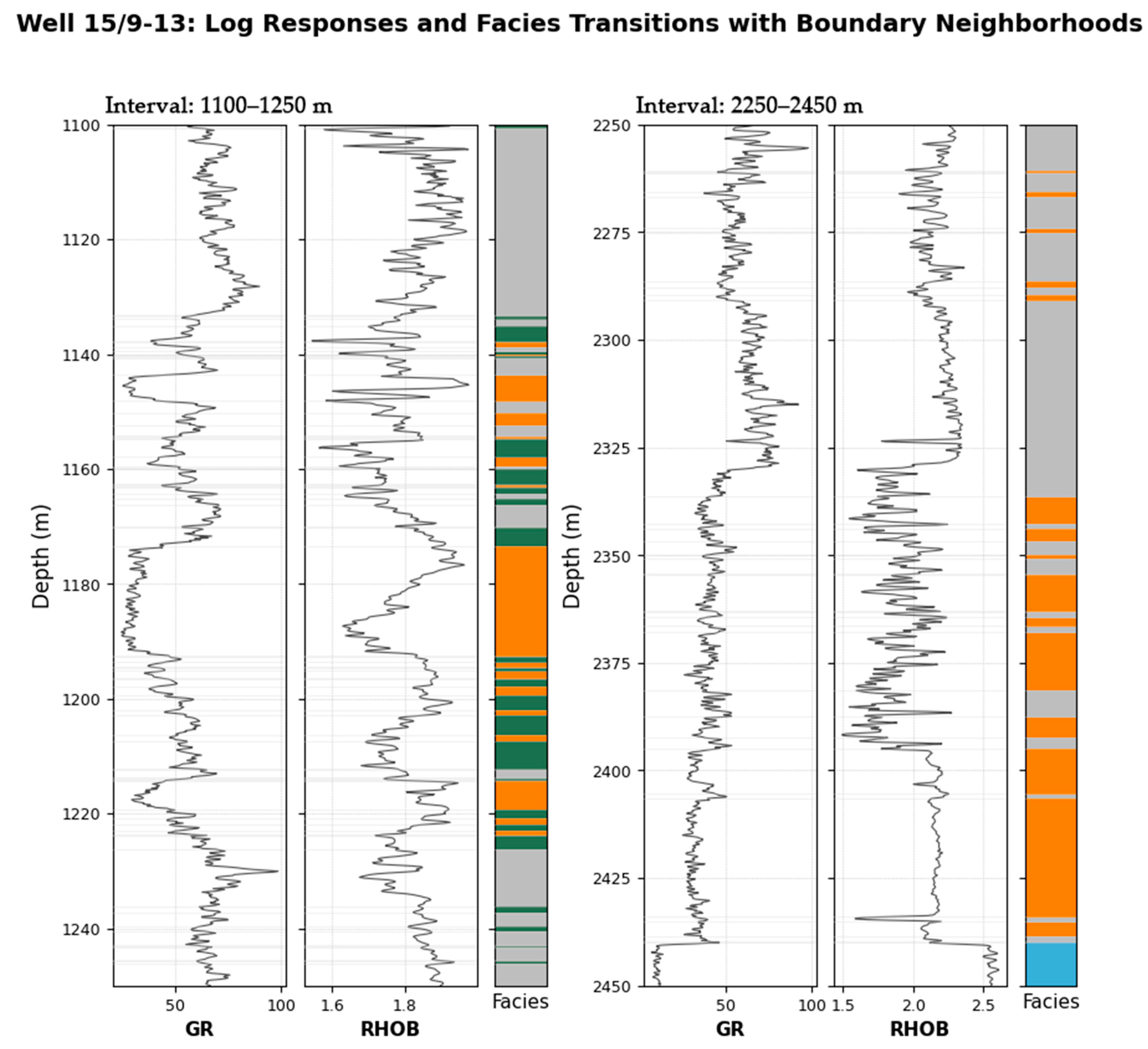

2.1. Dataset and Data Analysis

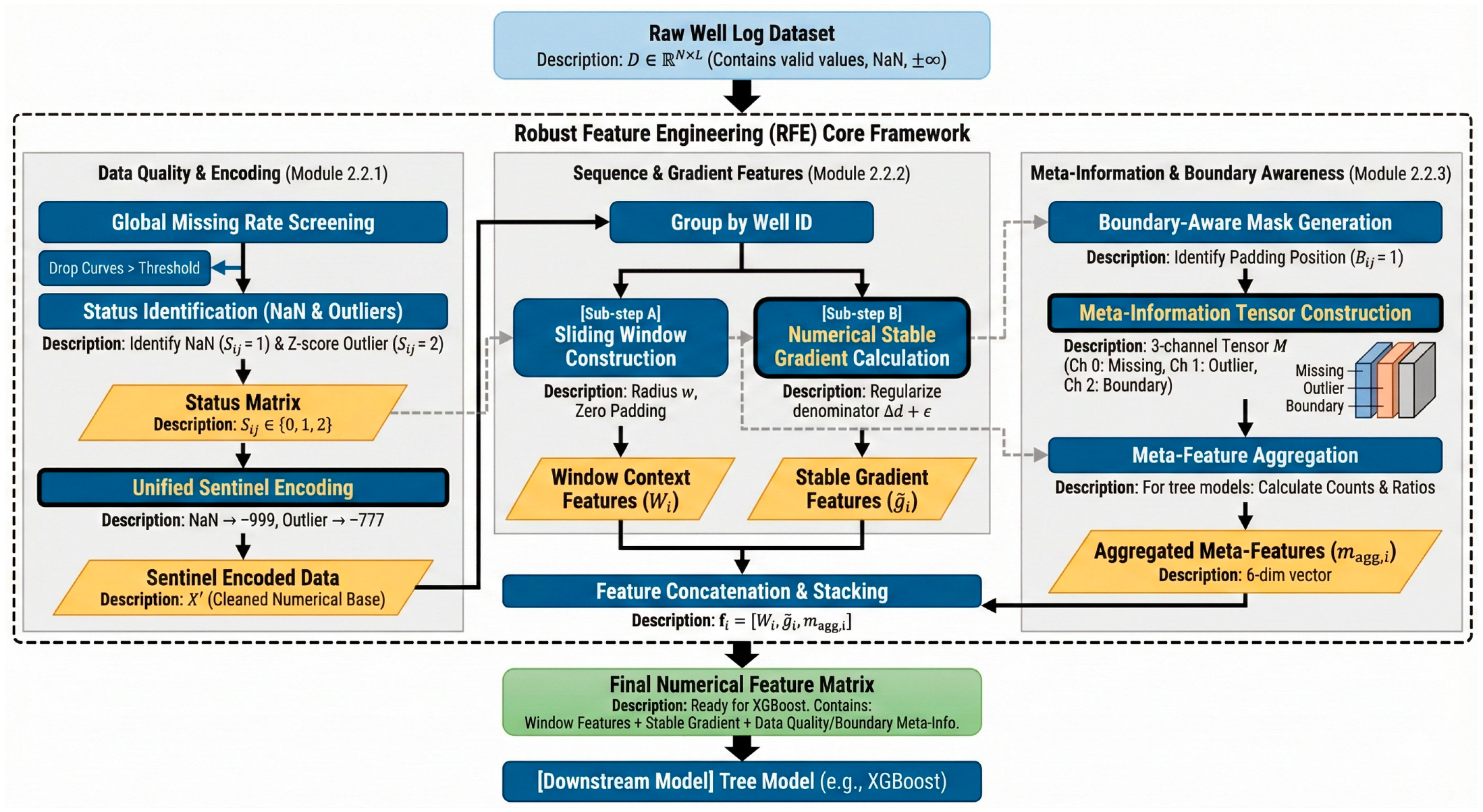

2.2. Robust Feature Engineering (RFE) Framework

2.2.1. Global Missing-Rate Filtering and Unified Sentinel Encoding

2.2.2. Sliding-Window Context Features and Numerically Stable Gradients

2.2.3. Boundary-Aware Mask and Meta-Information Tensor

2.3. Quality-Aware XGBoost Model

- 1.

- : Inverse to class frequency, balancing rare lithologies:

- 2.

- : To enhance the model’s sensitivity to lithological transitions, we assign higher penalties to boundary samples [53]:

- 3.

- : To suppress noise from poor-quality logs, we down-weight samples from wells with severe data loss. Let be the global missing rate of a well. The confidence weight is defined as:

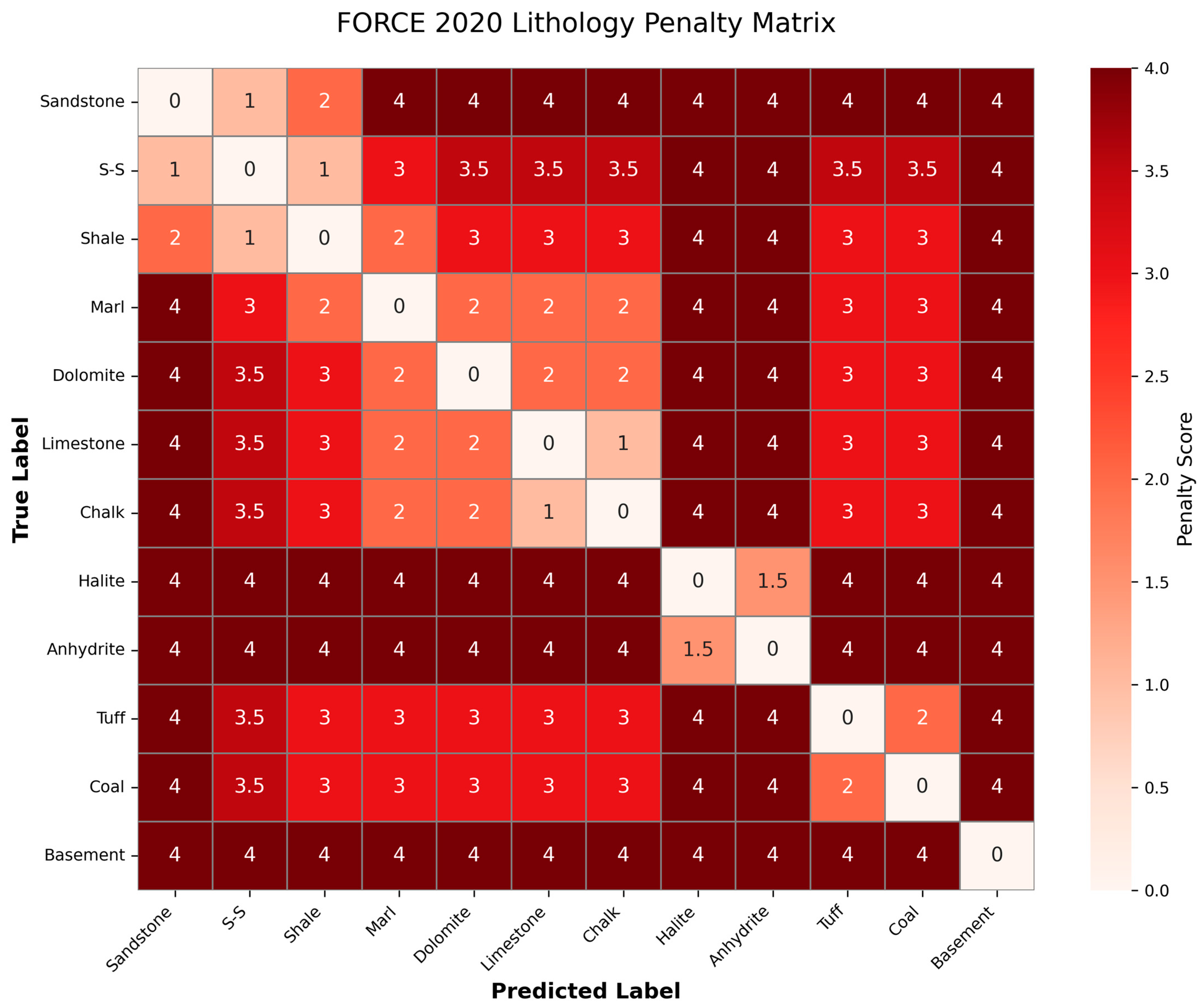

2.4. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

- Weighted F1-Score: To account for class imbalance, we adopt the Weighted F1-Score;

- Boundary F1 Score: Evaluates performance strictly on a boundary sample set defined as indices within radius of a transition

- 3.

3. Results

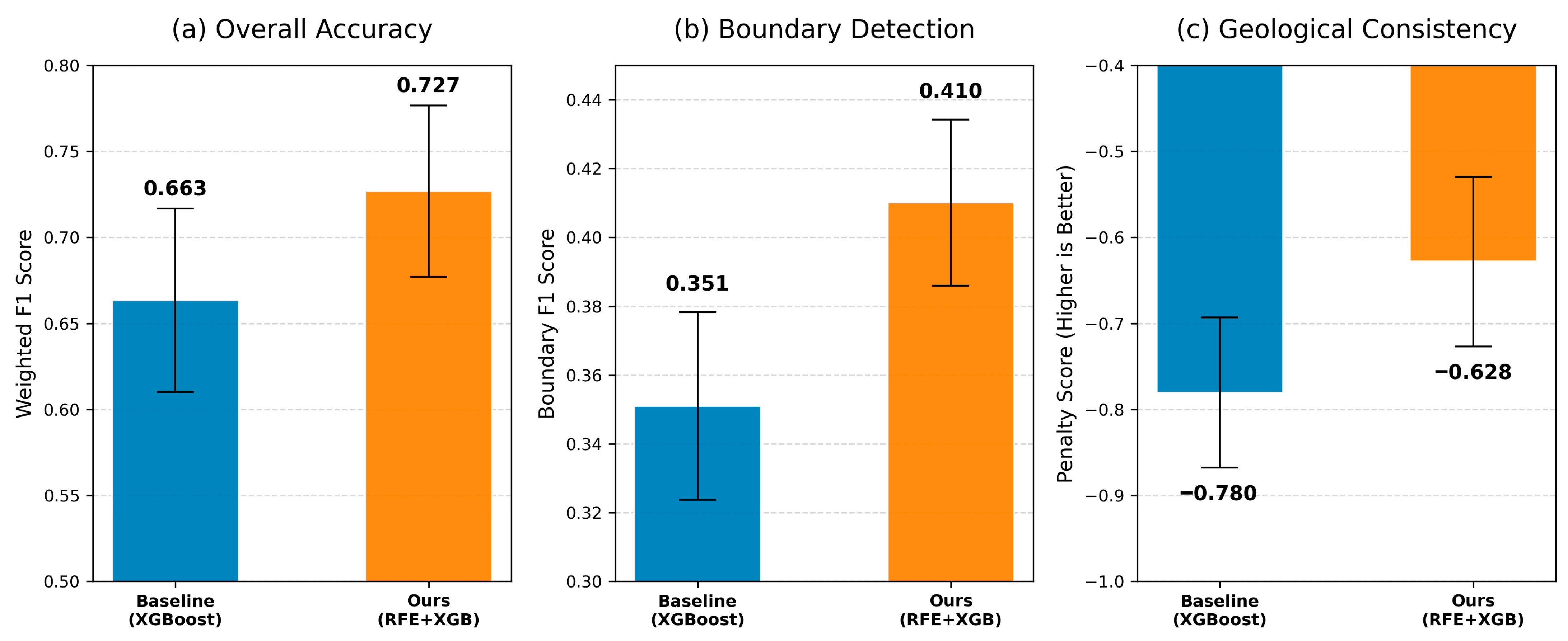

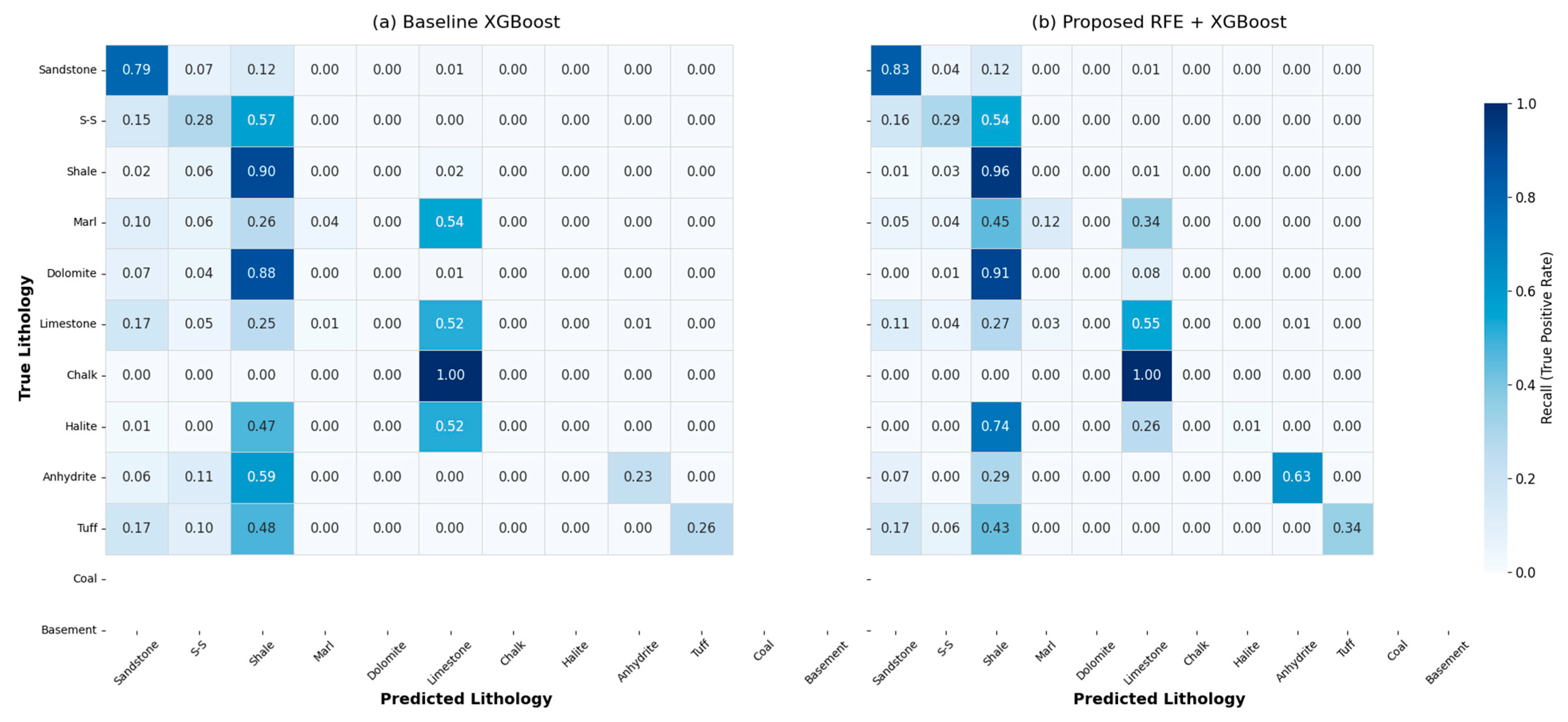

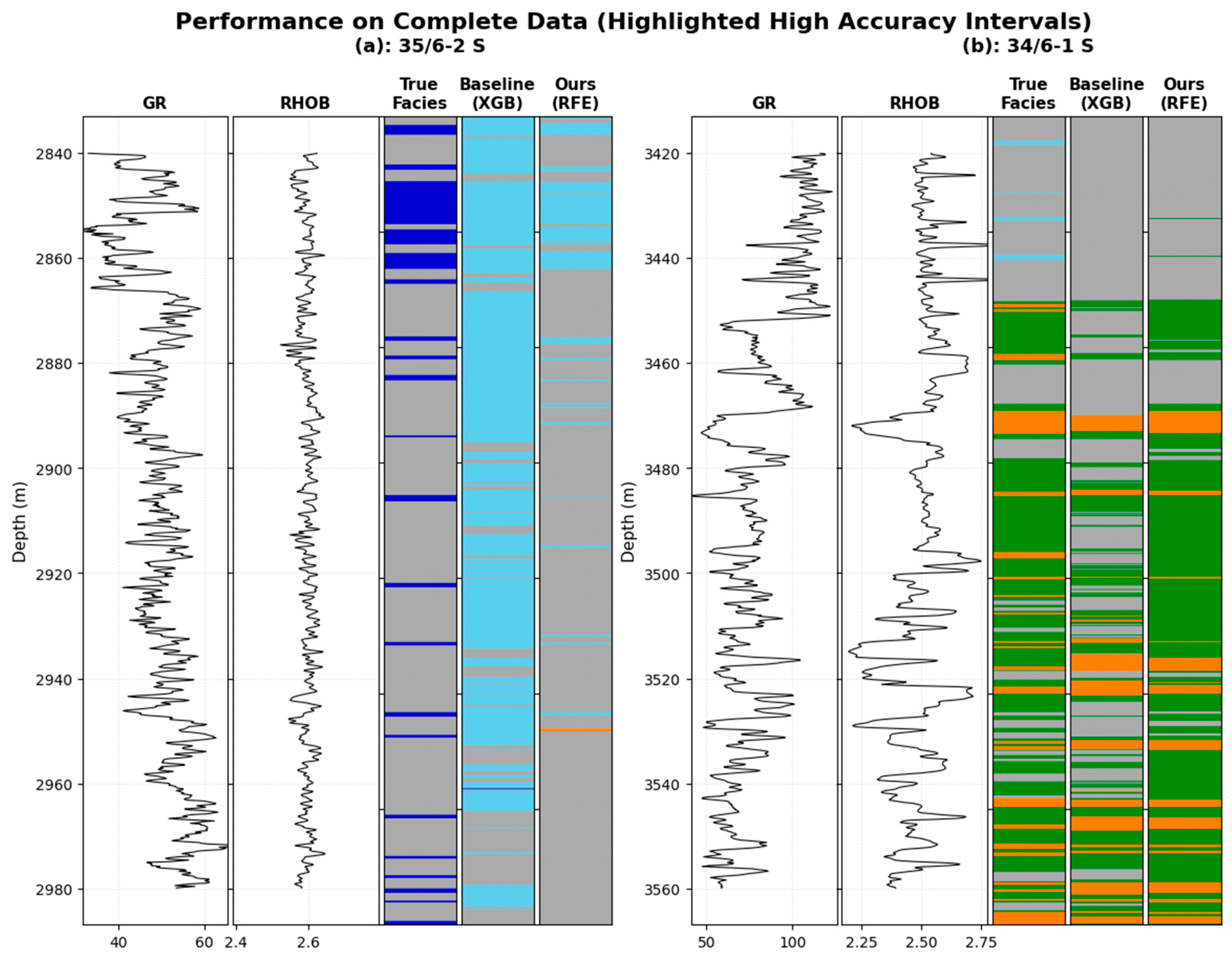

3.1. Baseline Comparison and Ablation Study

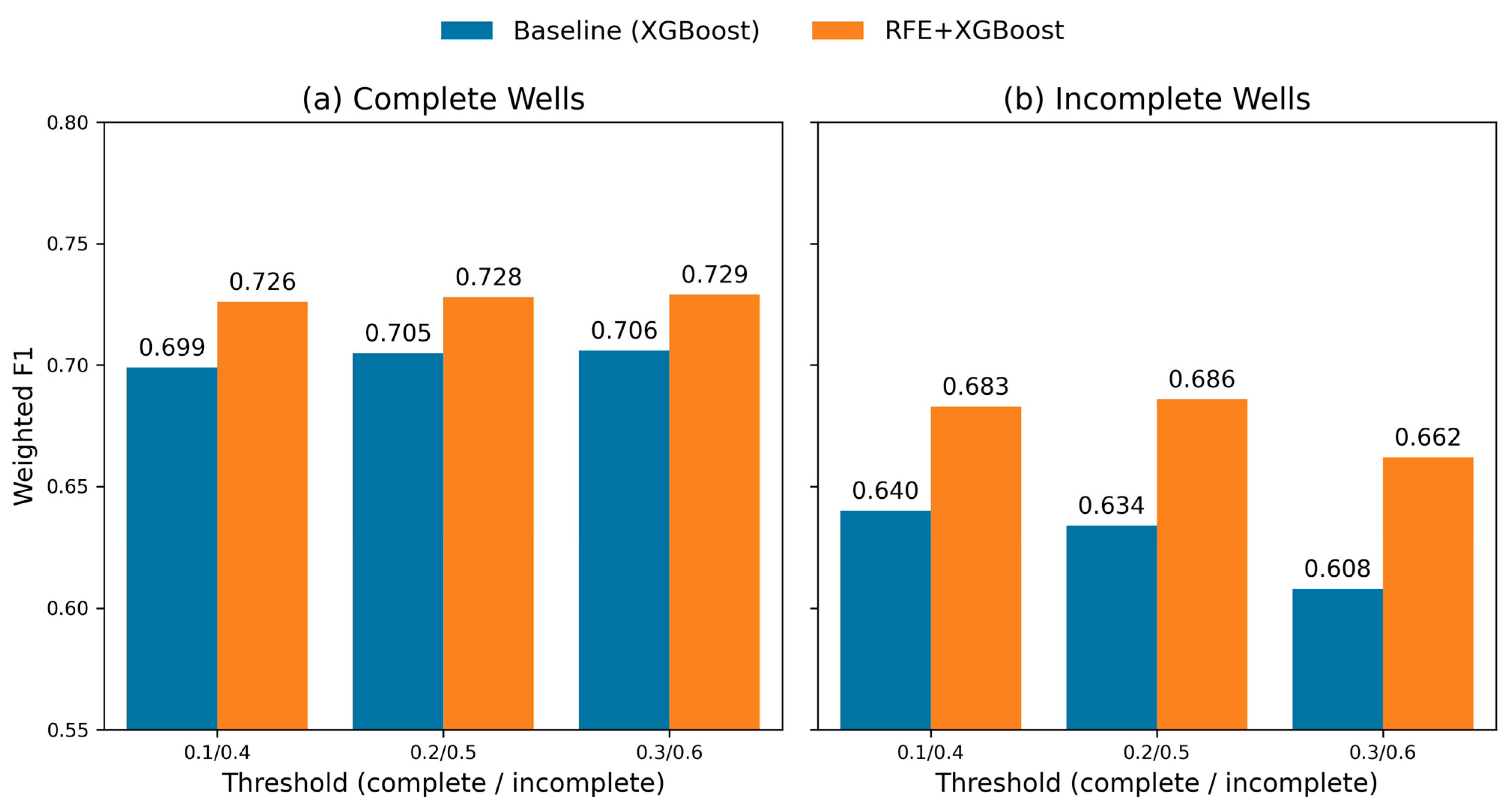

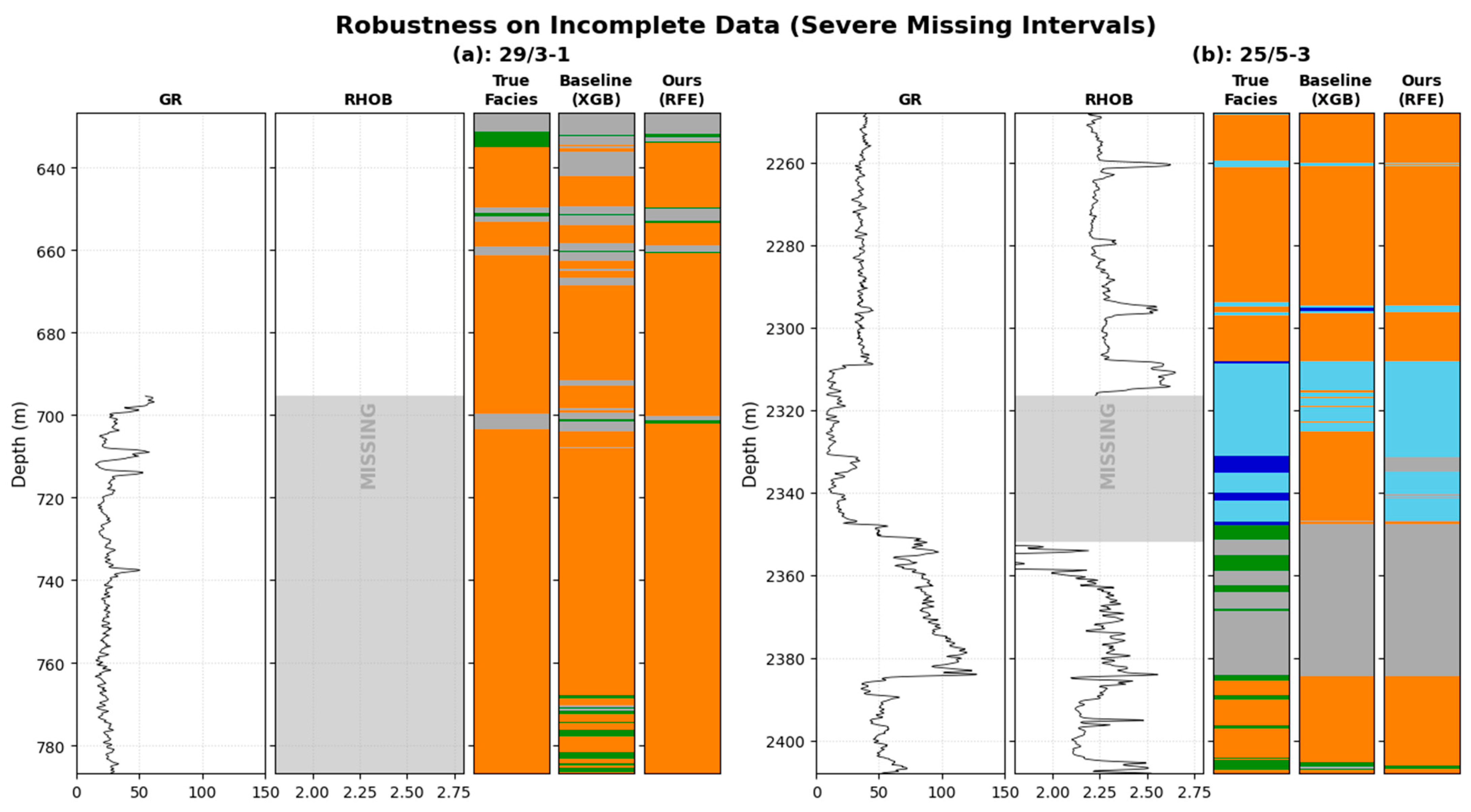

3.2. Robustness Analysis Under Varying Data Completeness

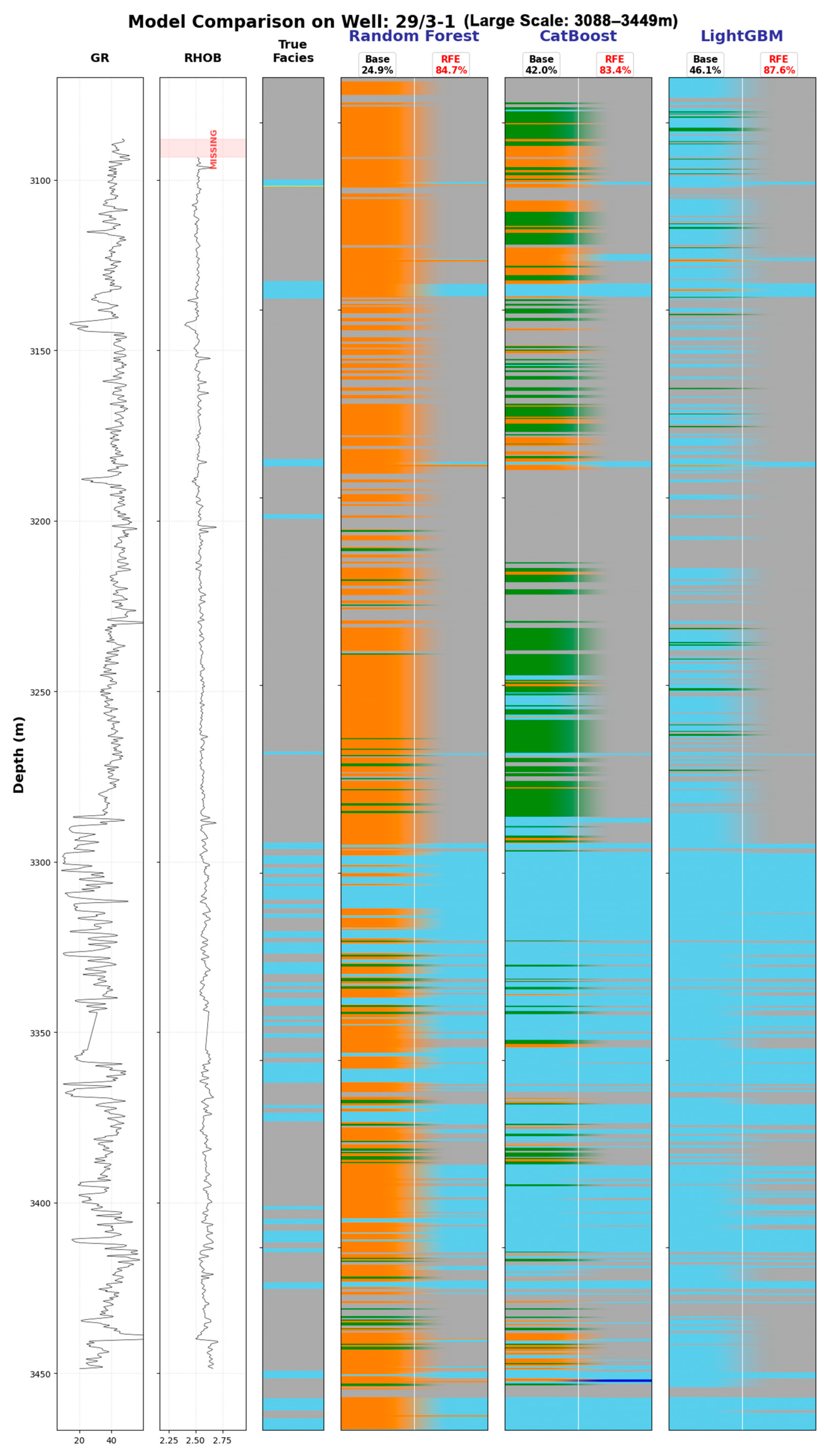

3.3. Applicability on Different Tree Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism Analysis: Why RFE Suits Tree Models Better than Interpolation

4.2. Geological Consistency and Engineering Safety

4.3. Boundary Delineation Capabilities

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wood, D.A. Extracting Useful Information from Sparsely Logged Wellbores for Improved Rock Typing of Heterogeneous Reservoir Characterization Using Well-Log Attributes, Feature Influence and Optimization. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 2307–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fan, Y. Fast Inversion of Logging-While-Drilling Azimuthal Resistivity Measurements for Geosteering and Formation Evaluation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 176, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Hou, M.; Chen, A.; Zhong, H.; Qi, Z.; Ren, Q.; You, J.; Wang, H.; Ma, C. Application of Machine Learning in the Identification of Fluvial-Lacustrine Lithofacies from Well Logs: A Case Study from Sichuan Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 215, 110610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, D. Lithofacies Identification from Well-Logging Curves via Integrating Prior Knowledge into Deep Learning. Geophysics 2024, 89, D31–D41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B. Facies Classification Using Machine Learning. Lead. Edge 2016, 35, 906–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, A.; Mukherjee, D.; Chassagne, R. Multivariate Imputation via Chained Equations for Elastic Well Log Imputation and Prediction. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 2022, 14, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, P.; Aursand, P.; Dilib, F.; Manral, S.; Dischington, P. FORCE 2020 Well Well Log and Lithofacies Dataset for Machine Learning Competition; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/4351156 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- The FORCE 2020 Machine Learning Contest with Wells and Seismic. Available online: https://www.sodir.no/en/force/Previous-events/2020/machine-learning-contest-with-wells-and-seismic (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Equinor. Force-Ml-2020-Wells. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/bolgebrygg/Force-2020-Machine-Learning-competition (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Gama, P.H.T.; Faria, J.; Sena, J.; Neves, F.; Riffel, V.R.; Perez, L.; Korenchendler, A.; Sobreira, M.C.A.; Machado, A.M.C. Imputation in Well Log Data: A Benchmark for Machine Learning Methods. Comput. Geosci. 2025, 196, 105789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Liu, D.; Lu, J.; Qiu, F.; Hu, J.; Li, Z.; Gamage, R.P. A Review of Machine Learning Applications to Geophysical Logging Inversion of Unconventional Gas Reservoir Parameters. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 258, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, L.; Huang, G.; Shang, Z.; Sun, J. A Review on Intelligent Recognition with Logging Data: Tasks, Current Status and Challenges. Surv. Geophys. 2024, 45, 1493–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamverdiyev, Y.; Sukhostat, L. Lithological Facies Classification Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 174, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Li, H.; Liu, N.; Gao, J.; Li, Z. Automatic Lithology Identification by Applying LSTM to Logging Data: A Case Study in X Tight Rock Reservoirs. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 18, 1361–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Pang, S.; Li, H.; Qiao, S.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced Lithology Classification Using an Interpretable SHAP Model Integrating Semi-Supervised Contrastive Learning and Transformer with Well Logging Data. Nat. Resour. Res. 2025, 34, 785–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Hou, J.; Song, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Dou, L. Lithology Identification Using Well Logs: A Method by Integrating Artificial Neural Networks and Sedimentary Patterns. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 182, 106336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Chen, C.; Li, W.; Pang, S. Multi-Domain Masked Reconstruction Self-Supervised Learning for Lithology Identification Using Well-Logging Data. Knowl. Based Syst. 2025, 323, 113843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Kang, Y.; Lv, W. Partial Domain Adaptation for Building Borehole Lithology Model Under Weaker Geological Prior. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 6645–6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, Z.; Li, K.; Liu, H.; Liu, G.; Lv, W. Cross-Well Lithology Identification Based on Wavelet Transform and Adversarial Learning. Energies 2023, 16, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Yang, X.; Xu, T.; Zeng, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Niu, Y.; Xiong, G. Semi-Supervised Neural Network for Complex Lithofacies Identification Using Well Logs. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5926519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhong, Z.; Hao, J.; Zeng, L. A Deep Kernel Method for Lithofacies Identification Using Conventional Well Logs. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 1411–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Z.; Purushotham, S.; Cho, K.; Sontag, D.; Liu, Y. Recurrent Neural Networks for Multivariate Time Series with Missing Values. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fakih, A.; Koeshidayatullah, A.; Mukerji, T.; Al-Azani, S.; Kaka, S.I. Well Log Data Generation and Imputation Using Sequence Based Generative Adversarial Networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Grana, D.; Balling, N. Imputation of Missing Well Log Data by Random Forest and Its Uncertainty Analysis. Comput. Geosci. 2021, 152, 104763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from Imbalanced Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.H.R.; Hosseini-Nasab, S.M. A Novel Approach to Classify Lithology of Reservoir Formations Using GrowNet and Deep-Insight with Physic-Based Feature Augmentation. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 4453–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Si, X.; Wu, X. FlexLogNet: A Flexible Deep Learning-Based Well-Log Completion Method of Adaptively Using What You Have to Predict What You Are Missing. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 191, 105666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhu, C.; Luo, W.; Wang, Q. Enhanced Cross-Domain Lithology Classification in Imbalanced Datasets Using an Unsupervised Domain Adversarial Network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-R.; Yang, R.-Z.; Li, T.-T.; Xu, Y.-D.; Sun, Z.-P. Reconstruction of Well-Logging Data Using Unsupervised Machine Learning-Based Outlier Detection Techniques (UML-ODTs) under Adverse Drilling Conditions. Appl. Geophys. 2025, 22, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Cho, Y. Imputation of Missing Values in Well Log Data Using K-Nearest Neighbor Collaborative Filtering. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 193, 105712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalsen, K.Ø.; Bianchi, F.M.; Soguero-Ruiz, C.; Jenssen, R. Time Series Cluster Kernel for Learning Similarities between Multivariate Time Series with Missing Data. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 76, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wei, H.; Wu, T.; Zhang, P.; Zhong, Z.; Li, C. Missing Well-Log Reconstruction Using a Sequence Self-Attention Deep-Learning Framework. Geophysics 2023, 88, D391–D410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Xu, Y.; Liao, H.; Liu, J.; Geng, Y.; Han, L. Missing Data Interpolation in Well Logs Based on Generative Adversarial Network and Improved Krill Herd Algorithm. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 246, 213538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elreedy, D.; Atiya, A.F. A Comprehensive Analysis of Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) for Handling Class Imbalance. Inf. Sci. 2019, 505, 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority over-Sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2999–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; Bahn, V.; Ciuti, S.; Boyce, M.; Elith, J.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Hauenstein, S.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.; Schröder, B.; Thuiller, W.; et al. Cross-Validation Strategies for Data with Temporal, Spatial, Hierarchical, or Phylogenetic Structure. Ecography 2016, 40, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Narayanan, A. Leakage and the Reproducibility Crisis in Machine-Learning-Based Science. Patterns 2023, 4, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, M.; Tejavibulya, L.; Jiang, R.; Noble, S.; Scheinost, D. Data Leakage Inflates Prediction Performance in Connectome-Based Machine Learning Models. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasiak, N.; Dejoux, J.-F.; Monteil, C.; Sheeren, D. Spatial Dependence between Training and Test Sets: Another Pitfall of Classification Accuracy Assessment in Remote Sensing. Mach. Learn. 2022, 111, 2715–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, A. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Labeled Data Can Bias the Validation and Selection of Supervised Learning Algorithms: A Marine Remote Sensing Example. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 187, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.J.; Garland, L.; Ochoa, J.; Pyrcz, M.J. Fair Train-Test Split in Machine Learning: Mitigating Spatial Autocorrelation for Improved Prediction Accuracy. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 209, 109885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Khodadadzadeh, M.; Zurita-Milla, R. Spatial+: A New Cross-Validation Method to Evaluate Geospatial Machine Learning Models. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 121, 103364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D.; Delarue, A.; Pauphilet, J. Adaptive Optimization for Prediction with Missing Data. Mach. Learn. 2025, 114, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josse, J.; Chen, J.M.; Prost, N.; Varoquaux, G.; Scornet, E. On the Consistency of Supervised Learning with Missing Values. Stat. Pap. 2024, 65, 5447–5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz-Ziv, R.; Armon, A. Tabular Data: Deep Learning Is Not All You Need. Inf. Fusion 2022, 81, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Zhu, P.; Huolin, M.; Pan, H.; Abbas, K.; Ashraf, U.; Ullah, J.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, H. A Novel Machine Learning Approach for Detecting Outliers, Rebuilding Well Logs, and Enhancing Reservoir Characterization. Nat. Resour. Res. 2023, 32, 1047–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zou, C.; Zhang, S.; Shu, J.; Wang, C. Geophysical Logs as Proxies for Cyclostratigraphy: Sensitivity Evaluation, Proxy Selection, and Paleoclimatic Interpretation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 252, 104735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Fu, Y. Lithology Recognition and Porosity Prediction from Well Logs Based on Convolutional Neural Networks and Sliding Window. J. Appl. Geophys. 2025, 242, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. Geological Information-Driven Deep Learning for Lithology Identification from Well Logs. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1662760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, S. Improving GBDT Performance on Imbalanced Datasets: An Empirical Study of Class-Balanced Loss Functions. Neurocomputing 2025, 634, 129896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Tang, J.; Li, Y.; Fu, S.; Tian, Y. MVQS: Robust Multi-View Instance-Level Cost-Sensitive Learning Method for Imbalanced Data Classification. Inf. Sci. 2024, 675, 120467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S. DECIDE: A Decoupled Semantic and Boundary Learning Network for Precise Osteosarcoma Segmentation by Integrating Multi-Modality MRI. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 174, 108308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adin, A.; Krainski, E.T.; Lenzi, A.; Liu, Z.; Martínez-Minaya, J.; Rue, H. Automatic Cross-Validation in Structured Models: Is It Time to Leave out Leave-One-out? Spat. Stat. 2024, 62, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, P.; Romero-Garcia, N.; Badenes, R.; Lora-Pablos, D.; Morales, T.G.; Gómez de la Cámara, A.; García-Gómez, J.M.; Sáez, C. Extremely Missing Numerical Data in Electronic Health Records for Machine Learning Can Be Managed through Simple Imputation Methods Considering Informative Missingness: A Comparative of Solutions in a COVID-19 Mortality Case Study. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 242, 107803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lim, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, D. Evaluating Missing Data Handling Methods for Developing Building Energy Benchmarking Models. Energy 2024, 308, 132979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yan, F.; Qiao, F.; Wang, J.; Qian, Y. Fusing Monotonic Decision Tree Based on Related Family. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinsztajn, L.; Oyallon, E.; Varoquaux, G. Why Do Tree-Based Models Still Outperform Deep Learning on Typical Tabular Data? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Q.; Lan, C.; Zhang, H.; Tan, W.; Xiao, J.; Pu, S. UN-η: An Offline Adaptive Normalization Method for Deploying Transformers. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 300, 112141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Datta Gupta, S.; Devi, V.; Yalamanchi, P. Using Rock Physics Analysis Driven Feature Engineering in ML-Based Shear Slowness Prediction Using Logs of Wells from Different Geological Setup. Acta Geophys. 2024, 72, 3237–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, B.; Cao, Z. Well Logging Super-Resolution Based on Fractal Interpolation Enhanced by BiLSTM-AMPSO. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2025, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonenko, A.R.; Petrov, A.M.; Danilovskiy, K.N. A Method for Correction of Shoulder-Bed Effect on Resistivity Logs Based on a Convolutional Neural Network. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2023, 64, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Shi, Y.; Bamber, J.L.; Tuo, Y.; Ludwig, R.; Zhu, X.X. Physics-Aware Machine Learning Revolutionizes Scientific Paradigm for Process-Based Modeling in Hydrology. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2025, 271, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class of Rock | Facies | Label | Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sandstone | 0 | SS | ████ |

| Sandstone/Shale | 1 | SS-Sh | ████ |

| Shale | 2 | Sh | ████ |

| Marl | 3 | Marl | ████ |

| Dolomite | 4 | Dol | ████ |

| Limestone | 5 | Lims | ████ |

| Chalk | 6 | Chlk | ████ |

| Halite | 7 | Hal | ████ |

| Anhydrite | 8 | Anhy | ████ |

| Tuff | 9 | Tuf | ████ |

| Coal | 10 | Coal | ████ |

| Basement | 11 | Bsmt | ████ |

| Model Configuration | FE | Weighing | F1 | Penalty Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (XGBoost) | × | × | 66.35 | −0.7804 |

| Baseline + Weighting | × | √ | 72.3 | −0.6346 |

| Baseline + FE | √ | × | 72.59 | −0.6327 |

| RFE + XGBoost | √ | √ | 72.72 | −0.6289 |

| Proportion | Model | Com/Incom | Weighted F1 | Boundary F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1/0.4 | XGBoost | Complete | 0.699 | 0.385 |

| 0.1/0.4 | XGBoost | Incomplete | 0.640 | 0.371 |

| 0.1/0.4 | Ours | Complete | 0.726 | 0.407 |

| 0.1/0.4 | Ours | Incomplete | 0.683 | 0.387 |

| 0.2/0.5 | XGBoost | Complete | 0.705 | 0.390 |

| 0.2/0.5 | XGBoost | Incomplete | 0.634 | 0.357 |

| 0.2/0.5 | Ours | Complete | 0.728 | 0.404 |

| 0.2/0.5 | Ours | Incomplete | 0.686 | 0.378 |

| 0.3/0.6 | XGBoost | Complete | 0.706 | 0.394 |

| 0.3/0.6 | XGBoost | Incomplete | 0.608 | 0.341 |

| 0.3/0.6 | Ours | Complete | 0.729 | 0.409 |

| 0.3/0.6 | Ours | Incomplete | 0.662 | 0.367 |

| Model | F1 | Boundary F1 | Penalty Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.6918 | 0.3840 | −0.6776 |

| RFE+RF | 0.7051 | 0.392 | −0.6467 |

| CatBoost | 0.6501 | 0.3510 | −0.7895 |

| RFE+CatBoost | 0.6866 | 0.3725 | −0.7156 |

| LightGBM | 0.6550 | 0.3768 | −0.808 |

| RFE+LightGBM | 0.7092 | 0.4147 | −0.6691 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, W.; Zhong, G.; Diao, F.; Ding, P.; He, J. Lithology Identification from Well Logs via Meta-Information Tensors and Quality-Aware Weighting. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2026, 10, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10020047

Chen W, Zhong G, Diao F, Ding P, He J. Lithology Identification from Well Logs via Meta-Information Tensors and Quality-Aware Weighting. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2026; 10(2):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10020047

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Wenxuan, Guoyun Zhong, Fan Diao, Peng Ding, and Jianfeng He. 2026. "Lithology Identification from Well Logs via Meta-Information Tensors and Quality-Aware Weighting" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 10, no. 2: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10020047

APA StyleChen, W., Zhong, G., Diao, F., Ding, P., & He, J. (2026). Lithology Identification from Well Logs via Meta-Information Tensors and Quality-Aware Weighting. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 10(2), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10020047