QU-Net: Quantum-Enhanced U-Net for Self Supervised Embedding and Classification of Skin Cancer Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Proposed Method

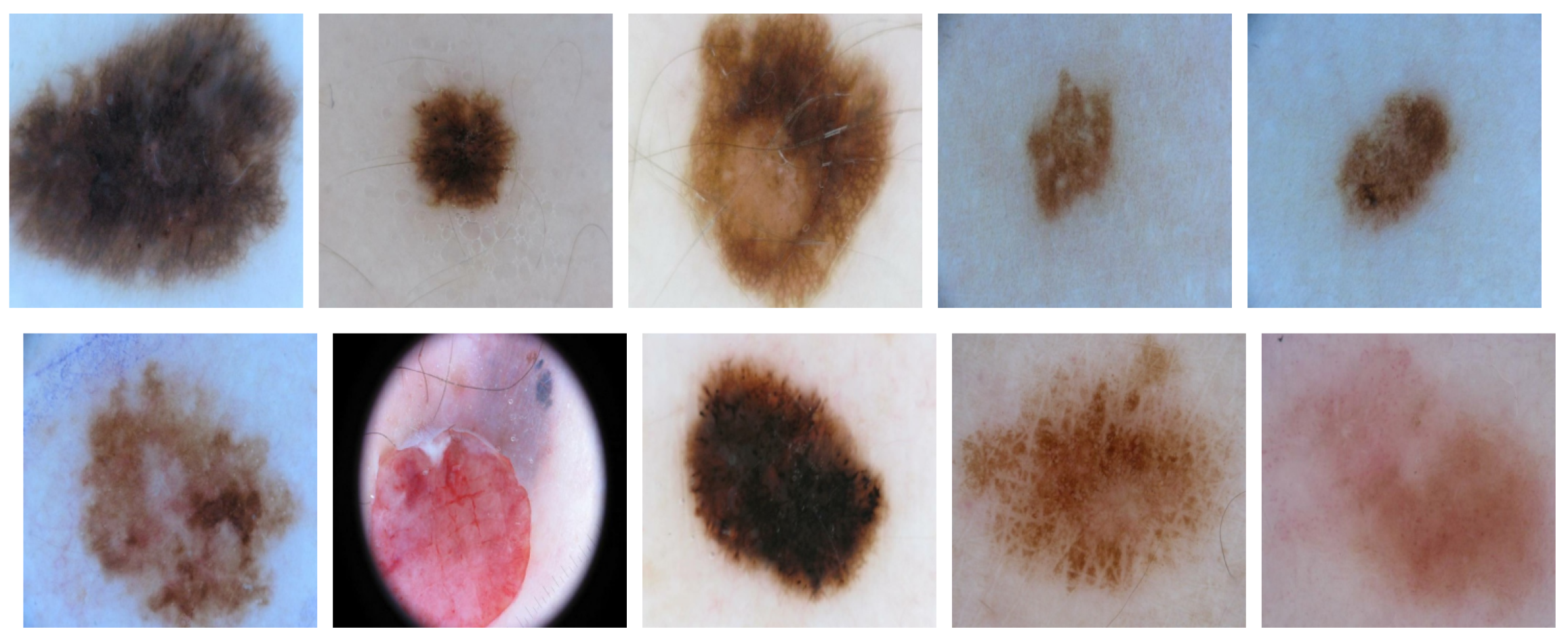

3.1. Data

- 2750 skin cancer images with different sizes.

- Classification labels

- Segmentation masks

- Metadata (age and sex)

3.2. Proposed Model

- Contracting Path (Encoder): The encoder is responsible for capturing context by progressively down-sampling the input image. This is achieved by a series of convolutional and max-pooling layers that reduce the spatial dimensions of the feature maps while increasing the depth.

- Bottleneck: The bottleneck serves as a bridge between the contracting and the expansive paths. Its design compresses the data flow into a limited set of values to capture the most essential information.

- Expansive Path (Decoder): The decoder is responsible for producing the desired output by expanding the feature maps. It consists of a series of up-sampling techniques (transposed convolutions, unpooling, …) and information fusion operations (concatenation, pixel-wise addition, …) with corresponding high-resolution features from the contracting path.

- Skip Connections: They serve to fuse up-sampled information from the bottleneck with high-resolution feature maps extracted by the encoder. They connect each layer in the encoder with its corresponding symmetric layer on the decoder.

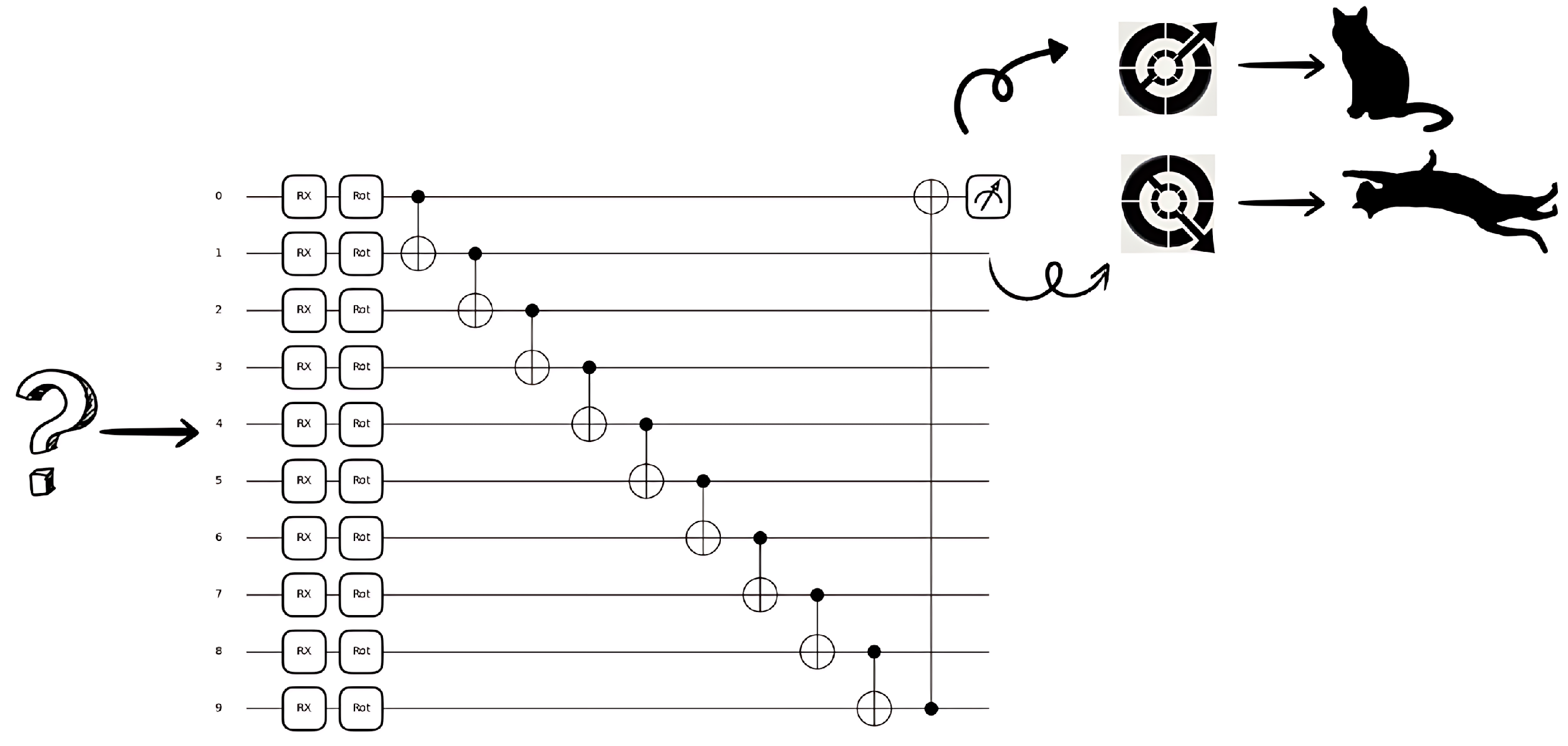

3.2.1. Parametrized Quantum Circuits

- Fixed gates: These are predefined operations that establish entanglement or transformations that do not change during training (CNOT, Hadamard, etc.).

- Parameterized gates: These are quantum operations that depend on adjustable parameters, usually represented as rotation angles (Rx, Ry, etc.).

- represents the unitary transformation at the i-th layer. It may contain multiple parameters or be parameter-free.

- L is the total number of layers.

- denotes the set of all trainable parameters.

3.2.2. Quantum State Preparation and Encoding

- Basis Encoding: Directly encoding classical bits into qubit states.

- Amplitude Encoding: Encoding classical data as quantum amplitudes, allowing compact representation.

- Angle Encoding: Encoding data using rotation angles of quantum gates.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Reconstruction

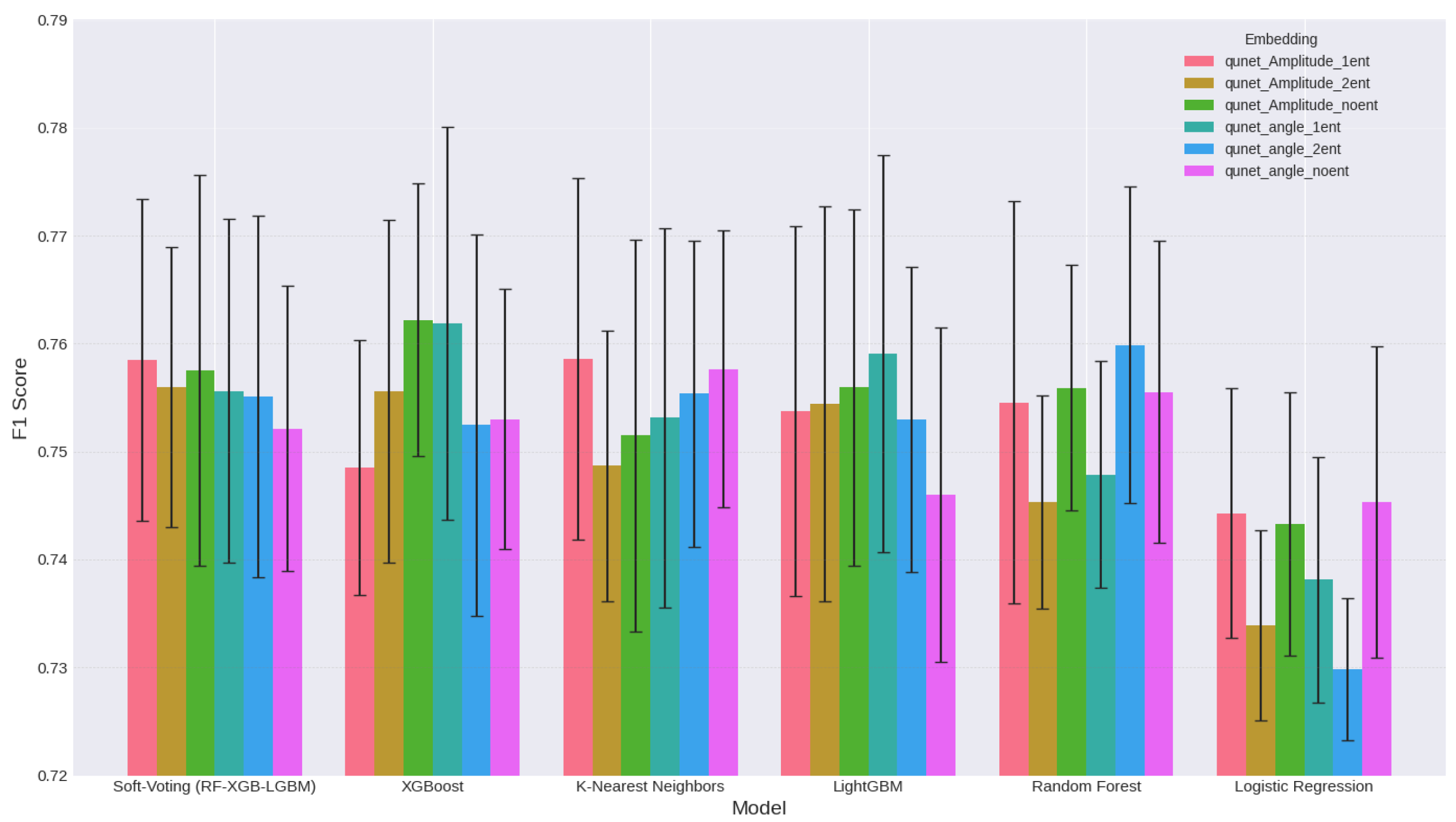

4.2. Classification

5. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QML | Quantum Machine Learning |

| ISIC | International Skin Imaging Collaboration |

| QU-Net | Quantum-Enhanced U-Net |

| PQC | Parameterized Quantum Circuit |

| QNN | Quantum Neural Network |

| BCC | Basal Cell Carcinoma |

| SCC | Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| NISQ | Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| QSVM | Quantum Support Vector Machine |

| QCNN | Quantum Convolutional Neural Network |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| FCL | Fully Connected Layer |

| VQC | Variational Quantum Circuit |

| IoMT | Internet of Medical Things |

| VQE | Variational Quantum Eigen-Solver |

| MHEA | Modified Hardware Efficient Ansatz |

| QuanvNN | Quanvolutional Neural Network |

| QPCA | Quantum Principal Component Analysis |

| RF | Random Forest |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

Appendix A. Quantum Machine Learning

Appendix A.1. Quantum Neural Networks

Structure of a Quantum Neural Network

- Data Encoding Layer: in this layer, we embed the classical representation of data into a quantum state in the space in order to manipulate it by the next parametrized gates. There are several encoding techniques, each with its advantages, like amplitude encoding and angle encoding [39].

- Parameterized Quantum Layers: This is the part where the quantum states are manipulated and prepared by parametrized gates; the parameters of these gates are adjusted during training to minimize a cost function.

- Measurement Layer: After applying the quantum layers, we take measurements of the quantum states to make predictions and compare them to ground labels.

Appendix A.2. Quantum Models Are Kernel Methods

Appendix A.3. The Parameter Shift Rule

Appendix B. CO2 Emissions

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| CO2 Emission per Hour | 244.125 g |

| Hours per Week | 35 |

| Total Duration (Weeks) | 10.43 weeks |

| Total Hours Worked | 365.05 h |

| Total CO2 Emission | 89.12 kg |

References

- Cerezo, M.; Verdon, G.; Huang, H.Y.; Cincio, L.; Coles, P.J. Challenges and opportunities in quantum machine learning. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2022, 2, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shor, P. Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 20–22 November 1994; pp. 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, L.K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, New York, NY, USA, 22–24 May 1996; STOC ’96. pp. 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, J.; Ahmed, S.; Schuld, M. Better than Classical? The Subtle Art of Benchmarking Quantum Machine Learning Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.07059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Skin Cancer. 2025. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/sun-safety/skin-cancer.html (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Codella, N.C.F.; Gutman, D.; Celebi, M.E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.A.; Dusza, S.W.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Mishra, N.; Kittler, H.; et al. Skin lesion analysis toward melanoma detection: A challenge at the 2017 International symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI), hosted by the international skin imaging collaboration (ISIC). In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018), Washington, DC, USA, 4–7 April 2018; pp. 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, V.; Kumar, M.; Gupta, A.; Sachdeva, M.; Mittal, A.; Saluja, K. Self-supervised learning for medical image analysis: A comprehensive review. Evol. Syst. 2024, 15, 1607–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Culp, L.; Freyberg, J.; Mustafa, B.; Baur, S.; Kornblith, S.; Chen, T.; Tomasev, N.; Mitrović, J.; Strachan, P.; et al. Robust and data-efficient generalization of self-supervised machine learning for diagnostic imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 756–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahlschmidt, S.; Ulfenborg, B.; Synnergren, J. Multimodal deep learning for biomedical data fusion: A review. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S.; Schuld, M.; Ijaz, A.; Izaac, J.; Killoran, N. Quantum embeddings for machine learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.03622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hengjin, k.; Cai, C. Deep Wavelet Self-Attention Non-negative Tensor Factorization for non-linear analysis and classification of fMRI data. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 182, 113522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Knackstedt, T.; Yan, S.; Hassanpour, S. Artificial intelligence-based image classification methods for diagnosis of skin cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 127, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Nasrolahzadeh, M.; Mohammadpoory, Z.; Zare Kordkheili, A. Skin Lesion Classification via ensemble method on deep learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 84, 19379–19397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xiang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Du, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H. Multi-Scale Transformer Architecture for Accurate Medical Image Classification. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computational Intelligence, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14–16 February 2025; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinthya, M.; Yustanti, W.; Nuryana, I.K.D.; Putra, C.D.; Putra, R.W.; Dayu, D.P.K.; Faradilla, A.E.; Kurniasari, C.I. Automated Skin Cancer Classification Using VGG16-Based Deep Learning Model. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, Surabaya, Indonesia, 5 July 2025; Volume 645, p. 04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; Bromley, T.R.; Izaac, J.; Schuld, M.; Killoran, N. Transfer learning in hybrid classical-quantum neural networks. Quantum 2020, 4, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagingalieva, A.; Kordzanganeh, M.; Kenbayev, N.; Kosichkina, D.; Tomashuk, T.; Melnikov, A. Hybrid quantum neural network for drug response prediction. Cancers 2023, 15, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahwar, T.; Zafar, J.; Almogren, A.; Zafar, H.; Rehman, A.U.; Shafiq, M.; Hamam, H. Automated detection of Alzheimer’s via hybrid classical quantum neural networks. Electronics 2022, 11, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebentrost, P.; Mohseni, M.; Lloyd, S. Quantum Support Vector Machine for Big Data Classification. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 130503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhuri, R.; Halder, A. Brain MRI tumour classification using quantum classical convolutional neural net architecture. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 35, 4467–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Li, Y.; Tiwari, P. QNMF: A quantum neural network based multimodal fusion system for intelligent diagnosis. Inf. Fusion 2023, 100, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoieb, D.; Younes, A.; Youssef, S.; Fathalla, K. HQMC-CPC: A Hybrid Quantum Multiclass Cardiac Pathologies Classification Integrating a Modified Hardware Efficient Ansatz. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 18295–18314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathi, G.; Altalbe, A.; Kumar, R.P. QuCNet: Quantum-Inspired Convolutional Neural Networks for Optimized Thyroid Nodule Classification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 27829–27842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reka, S.; Karthikeyan, L.; Shakil, J.; Venugopal, P.; Muniraj, M. Exploring Quantum Machine Learning for Enhanced Skin Lesion Classification: A Comparative Study of Implementation Methods. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 104568–104584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Fujii, K. SantaQlaus: A resource-efficient method to leverage quantum shot-noise for optimization of variational quantum algorithms. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.15791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, M.; Hölle, M.; Periyasamy, M.; Meyer, N.; Ufrecht, C.; Scherer, D.D.; Plinge, A.; Mutschler, C. An Empirical Comparison of Optimizers for Quantum Machine Learning with SPSA-Based Gradients. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), Bellevue, WA, USA, 17–22 September 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Rashid, M.; Al-Kuwari, S.; Shafique, M. Alleviating Barren Plateaus in Parameterized Quantum Machine Learning Circuits: Investigating Advanced Parameter Initialization Strategies. In Proceedings of the 2024 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Valencia, Spain, 25–27 March 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nha Minh Le, I.; Kiss, O.; Schuhmacher, J.; Tavernelli, I.; Tacchino, F. Symmetry-invariant quantum machine learning force fields. New J. Phys. 2025, 27, 023015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T West, M.; Sevior, M.; Usman, M. Reflection equivariant quantum neural networks for enhanced image classification. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2023, 4, 035027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatkowski, N.; Gerlach, T.; Hugues, R.; Sifa, R.; Bauckhage, C.; Barbaresco, F. Towards Bundle Adjustment for Satellite Imaging via Quantum Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 25th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Linköping, Sweden, 4–7 July 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, S.; Stanev, D.; Santantonio, T.; Giagu, S. Long-Lived Particles Anomaly Detection with Parametrized Quantum Circuits. Particles 2023, 6, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, F.J.; Eisert, J.; Meyer, J.J. Classical Surrogates for Quantum Learning Models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 100803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Proceedings, Part III 18. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madabhushi, A.; Metaxas, D. Combining low-, high-level and empirical domain knowledge for automated segmentation of ultrasonic breast lesions. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2003, 22, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, K.; Cervera-Lierta, A.; Kyaw, T.H.; Haug, T.; Alperin-Lea, S.; Anand, A.; Degroote, M.; Heimonen, H.; Kottmann, J.S.; Menke, T.; et al. Noisy intermediate-scale quantum algorithms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2022, 94, 015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M.; Bocharov, A.; Svore, K.M.; Wiebe, N. Circuit-centric quantum classifiers. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 101, 032308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranga, D.; Rana, A.; Prajapaat, S.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, K.; Vasilakos, A. Quantum Machine Learning: Exploring the Role of Data Encoding Techniques, Challenges, and Future Directions. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M.; Sinayskiy, I.; Petruccione, F. The quest for a Quantum Neural Network. Quantum Inf. Process. 2014, 13, 2567–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, K.; Bondarenko, D.; Farrelly, T.; Osborne, T.; Salzmann, R.; Scheiermann, D.; Wolf, R. Training deep quantum neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, S.; Mohseni, M.; Rebentrost, P. Quantum Principal Component Analysis. Nat. Phys. 2014, 10, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M. Supervised quantum machine learning models are kernel methods. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.11020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubregtsen, T.; Wierichs, D.; Gil-Fuster, E.; Derks, P.J.H.S.; Faehrmann, P.K.; Meyer, J.J. Training quantum embedding kernels on near-term quantum computers. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 106, 042431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, G.E. Gradients of parameterized quantum gates using the parameter-shift rule and gate decomposition. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.13311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M.; Bergholm, V.; Gogolin, C.; Izaac, J.; Killoran, N. Evaluating analytic gradients on quantum hardware. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 032331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Method | Description | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| [13] | Inception-ResNet-v2 + EfficientNet-B4 | Ensemble with Soft-Attention | 79% |

| [14] | Improved ViT | Weighted loss + lesion-focused regularization | 88.4% |

| [14] | ResNet50/VGG19/ResNeXt/ViT | Baseline comparison models | 85.2%, 83.5%, 86%, 87% |

| [15] | Modified VGG-16 | Transfer learning approach | 71% |

| References | Tasks | Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | Patient drug response prediction | GCN for drugs + CNN for cell lines + QNN | 15% better than FCL |

| [18] | Alzheimer detection | ResNet34 + QSVM | 97.2% (QSVM) vs. 92.2% (classical) |

| [20] | Brain MRI binary classification | QCNN | 98.72% (QCNN) vs. 94.23% (CNN) |

| [21] | Breast cancer and COVID-19 diagnosis | QCNN + VQC | 97.07% (breast), 97.61% (COVID) |

| [22] | Cardiac pathology classification | QHEA + multimodal data | 3.19–7.77% better than other models |

| [23] | Thyroid cancer classification | Quantum filter + QCNN | 97.63% vs. 93.87% (classical) |

| [25] | Skin cancer classification (HAM10000) | QuanvNN + QSVM | 82.86% (QNN) vs. 73.42% (MobileNet) |

| Gate Name | Qubits | Circuit Symbol | Unitary Matrix | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pauli-X (NOT) | 1 |  | Analogous to classical NOT gate: switches to and vice versa | |

| Pauli-Y | 1 |  | Rotation through radians around Bloch sphere Y-axis | |

| Pauli-Z (phase flip) | 1 |  | Rotation through radians around Bloch sphere Z-axis | |

| X-Rotation | 1 |  | Rotates state vector about the Bloch sphere X-axis by | |

| Y-Rotation | 1 |  | Rotates state vector about the Bloch sphere Y-axis by | |

| Z-Rotation | 1 |  | Rotates state vector about the Bloch sphere Z-axis by | |

| Hadamard | 1 |  | Transforms a basis state into an even superposition of the two basis states | |

| CNOT (Controlled-NOT) | 2 |  | Applies Pauli-X to target qubit if control qubit is | |

| SWAP | 2 |  | Swaps the states of two qubits | |

| Rot () | 1 |  | A general rotation gate that combines rotations around Z and Y axes: . Provides flexible state preparation and transformation. |

| Amplitude | Angle | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss (MSE) | 1-Ent | 2-Ent | 1-NoEnt | 1-Ent | 2-Ent | 1-NoEnt | U-Net |

| Train | 0.000106 | 0.000079 | 0.000075 | 0.000084 | 0.000071 | 0.000072 | 0.000115 |

| Validation | 0.000133 | 0.000160 | 0.000155 | 0.000170 | 0.000146 | 0.000149 | 0.000147 |

| Test | 0.000151 | 0.000172 | 0.000172 | 0.000190 | 0.000165 | 0.000163 | 0.000172 |

| Classifier | U-Net | QU-Net | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 Score (%) | Accuracy (%) | F1 Score (%) | Accuracy (%) | |

| Random Forest (RF) | 74.14 | 81.33 | 75.86 | 80.17 |

| LightGBM (LGBM) | 72.93 | 79.33 | 76.68 | 80.17 |

| XGBoost (XGB) | 77.38 | 81.33 | 78.27 | 80.50 |

| Logistic Regression | 70.78 | 79.33 | 73.07 | 80.17 |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | 70.43 | 74.00 | 76.05 | 78.33 |

| Soft-Voting (RF-XGB-LGBM) | 73.33 | 80.00 | 79.03 | 81.83 |

| References | Method | Description | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| [15] | Modified VGG-16 | Transfer learning approach | 71% |

| [13] | Inception-ResNet-v2 + EfficientNet-B4 | Ensemble with Soft-Attention | 79% |

| Ours | QU-Net (quantum-enhanced U-Net) | Quantum embeddings + metadata + baseline classifier | 79.03% |

| [14] | ResNet50/VGG19/ ResNeXt/ViT | Baseline comparison models | 85.2%, 83.5%, 86%, 87% |

| [14] | Improved ViT | Weighted loss + lesion-focused regularization | 88.4% |

| Classifier | U-Net F1 | QU-Net F1 | Difference (Q − U) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 71.11 | 72.97 | +1.86 |

| LightGBM | 72.29 | 73.23 | +0.94 |

| XGBoost | 69.77 | 73.73 | +3.96 |

| Logistic Regression | 70.78 | 71.80 | +1.02 |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | 72.39 | 71.87 | −0.52 |

| Soft-Voting (RF–XGB–LGBM) | 71.00 | 72.78 | +1.78 |

| Classifier | U-Net | QU-Net | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Metadata (%) | Without Metadata (%) | With Metadata (%) | Without Metadata (%) | |

| Random Forest | F1: 74.14 | F1: 71.11 | F1: 75.86 | F1: 72.97 |

| Acc: 81.33 | Acc: 80.00 | Acc: 80.17 | Acc: 80.00 | |

| LightGBM | F1: 72.93 | F1: 72.29 | F1: 76.68 | F1: 73.23 |

| Acc: 79.33 | Acc: 80.00 | Acc: 80.17 | Acc: 78.83 | |

| XGBoost | F1: 77.38 | F1: 69.77 | F1: 78.27 | F1: 73.73 |

| Acc: 81.33 | Acc: 77.33 | Acc: 80.50 | Acc: 78.33 | |

| Logistic Regression | F1: 70.78 | F1: 70.78 | F1: 73.07 | F1: 71.80 |

| Acc: 79.33 | Acc: 79.33 | Acc: 80.17 | Acc: 80.50 | |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | F1: 70.43 | F1: 72.39 | F1: 76.05 | F1: 71.87 |

| Acc: 74.00 | Acc: 76.00 | Acc: 78.33 | Acc: 76.00 | |

| Soft-Voting (RF-XGB-LGBM) | F1: 73.33 | F1: 71.00 | F1: 79.03 | F1: 72.78 |

| Acc: 80.00 | Acc: 78.00 | Acc: 81.83 | Acc: 78.83 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Halab, K.; Marzoug, N.; El Meslouhi, O.; Abou Elassad, Z.E.; Akhloufi, M.A. QU-Net: Quantum-Enhanced U-Net for Self Supervised Embedding and Classification of Skin Cancer Images. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2026, 10, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010012

Halab K, Marzoug N, El Meslouhi O, Abou Elassad ZE, Akhloufi MA. QU-Net: Quantum-Enhanced U-Net for Self Supervised Embedding and Classification of Skin Cancer Images. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2026; 10(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalab, Khidhr, Nabil Marzoug, Othmane El Meslouhi, Zouhair Elamrani Abou Elassad, and Moulay A. Akhloufi. 2026. "QU-Net: Quantum-Enhanced U-Net for Self Supervised Embedding and Classification of Skin Cancer Images" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 10, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010012

APA StyleHalab, K., Marzoug, N., El Meslouhi, O., Abou Elassad, Z. E., & Akhloufi, M. A. (2026). QU-Net: Quantum-Enhanced U-Net for Self Supervised Embedding and Classification of Skin Cancer Images. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 10(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010012