NovAc-DL: Novel Activity Recognition Based on Deep Learning in the Real-Time Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

1.2. Motivation

- The model could improve surveillance systems by distinguishing between typical activity and questionable behavior, such as unauthorized pouring or stirring in forbidden regions.

- Recognizing certain behaviors in aged care could alert carers to atypical behaviors, enhancing patient monitoring and responsiveness.

- Identifying specific vehicle activities to prevent accidents and promote safer driving practices.

- Optimizing production by automating quality control by recognizing pour and stir activities.

1.3. Contribution

- We introduce NovAc-DL, a unified deep learning framework for fine-grained robotic action recognition using real-world “pour” and “stir” tasks, bridging human–robot collaboration domains.

- We conduct a comparative evaluation of three distinct spatiotemporal models, i.e., LRCN, ConvLSTM, and CNN-TD under identical dataset and preprocessing settings, providing quantitative insight into spatial vs. temporal representation strengths.

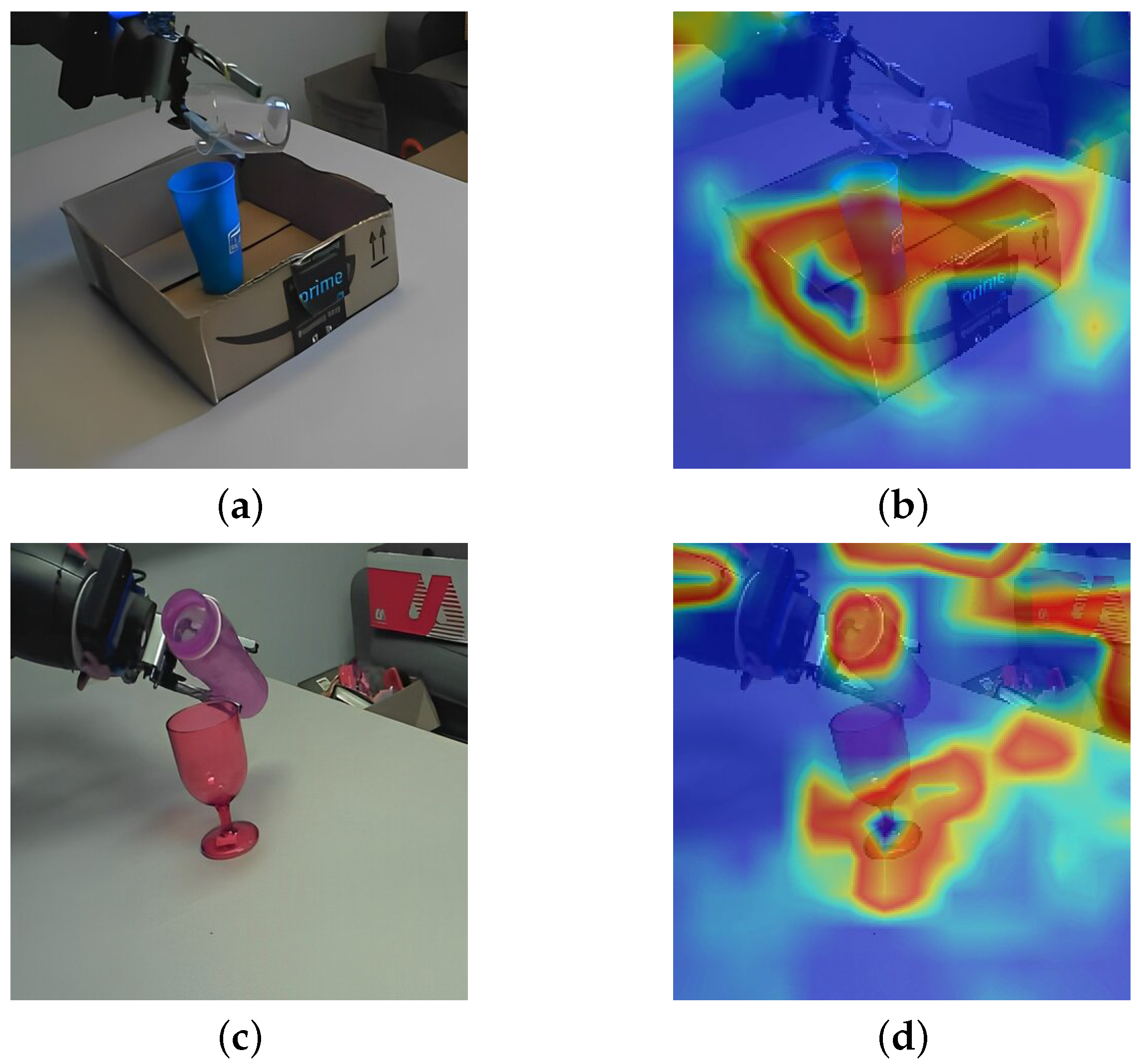

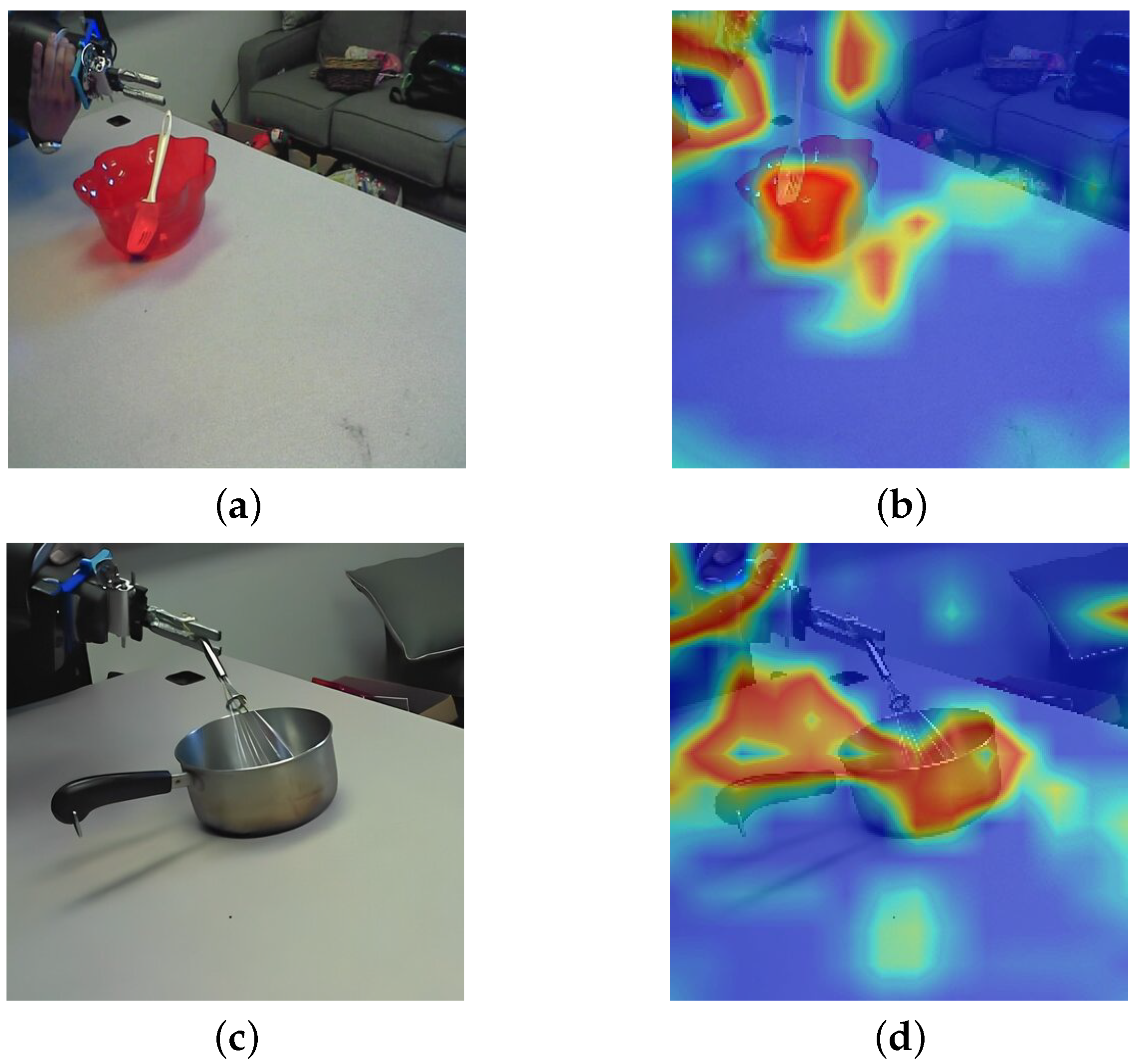

- We provide interpretability through Grad-CAM visualization, linking motion-specific activations to the physical regions of action (e.g., container–target interface during pouring and cyclic motion in stirring).

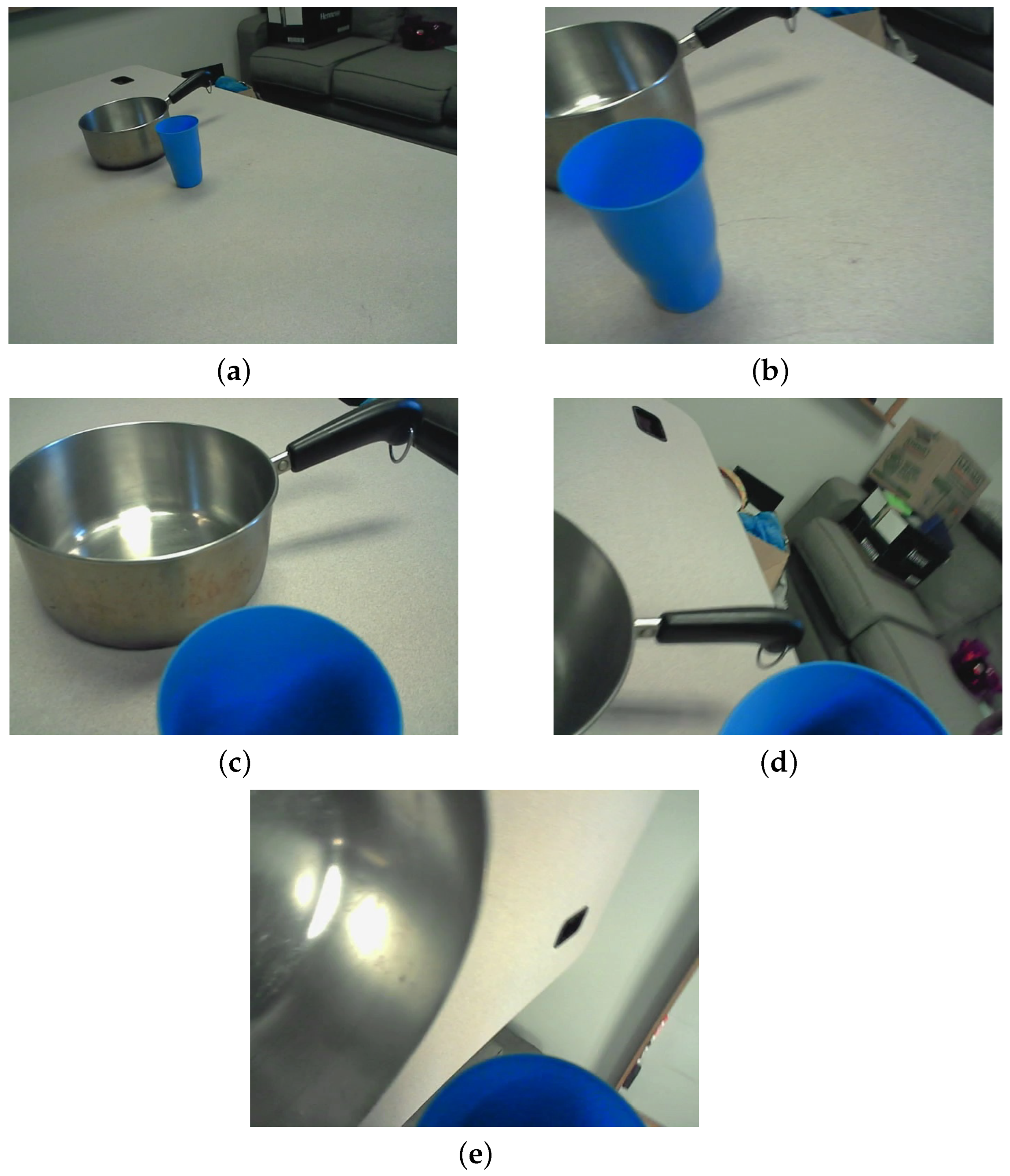

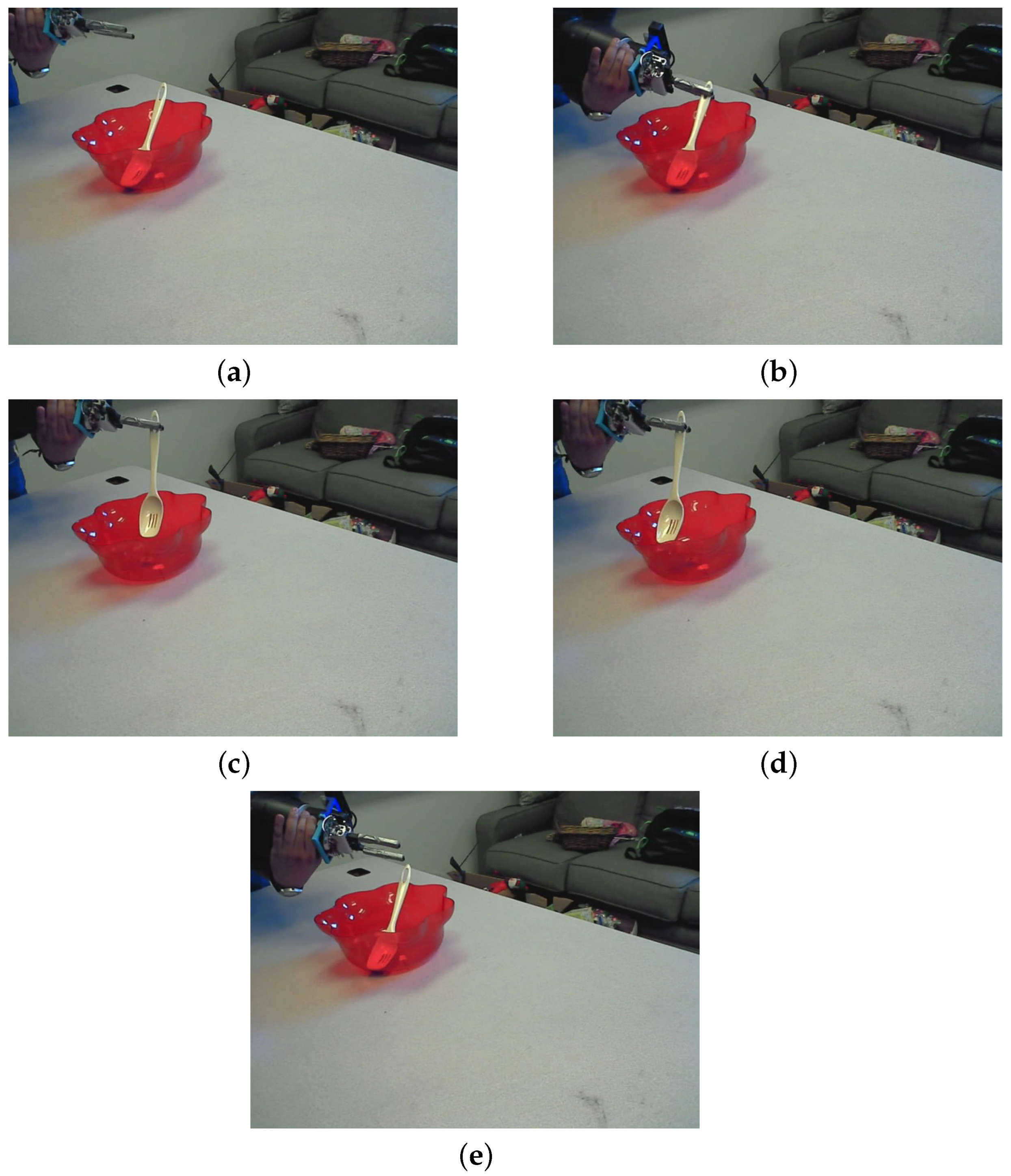

2. Related Dataset

2.1. Data Set Description

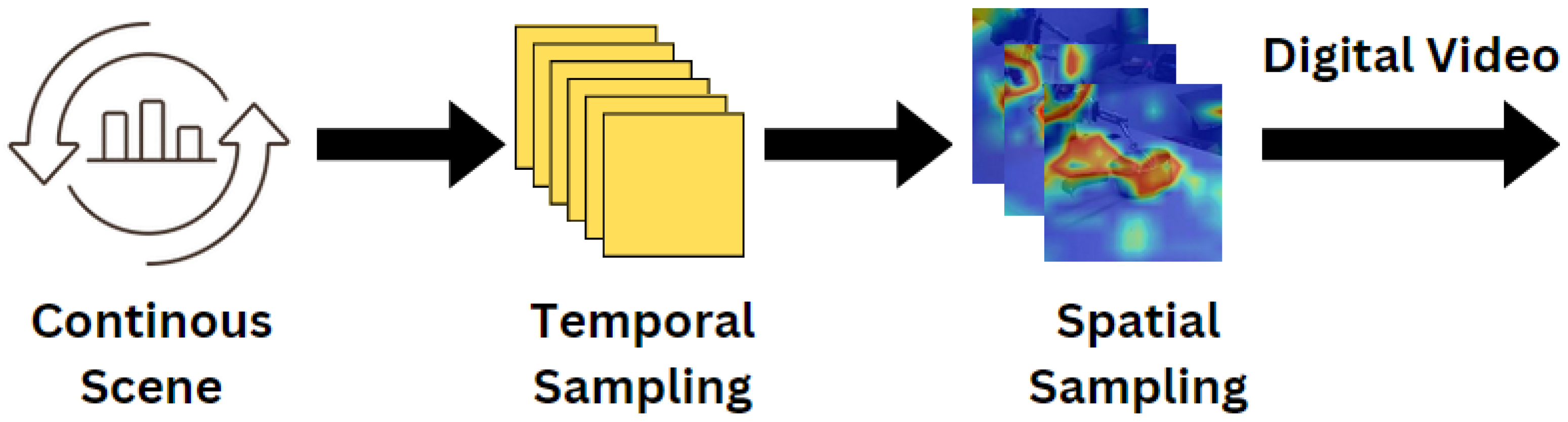

2.2. Data Preprocessing

- Initialize three empty lists: features, labels, and video_files_paths.

- For each class in CLASSES_LIST (which, in our case, would be ‘pour’ and ‘stir’), print out the class currently being processed.

- For each file in the directory of the current class, create the full path to the file and extract the frames from the video using the frame_extractor function.

- Append the extracted frames to the features list, the class index to the labels list, and the video file path to the video_files_paths list. The class index is derived from the enumeration of CLASSES_LIST.

- After all videos have been processed, the features and labels lists are converted into NumPy arrays, a more efficient data structure for subsequent data processing and modeling tasks.

- Finally, the function returns the features, labels, and video_files_paths. At the end of this function, features will contain all the frames of all the videos in a structured format, labels will contain the corresponding class labels, and video_files_paths will contain the file paths of the videos.

| Algorithm 1 Uniform Frame Extraction and Preprocessing |

| Require: video_path, desired_length , target size Ensure: A sequence of at most L preprocessed frames 1: Initialize an empty list F 2: Load the input video from video_path 3: total number of frames in the video 4: ▹ Sampling interval 5: for to do 6: Set video position to frame index 7: Read a frame from the video 8: if frame read fails then 9: break 10: end if 11: Resize the frame to 12: Convert pixel values to the range (normalization) 13: Append the normalized frame to F 14: end for 15: return F |

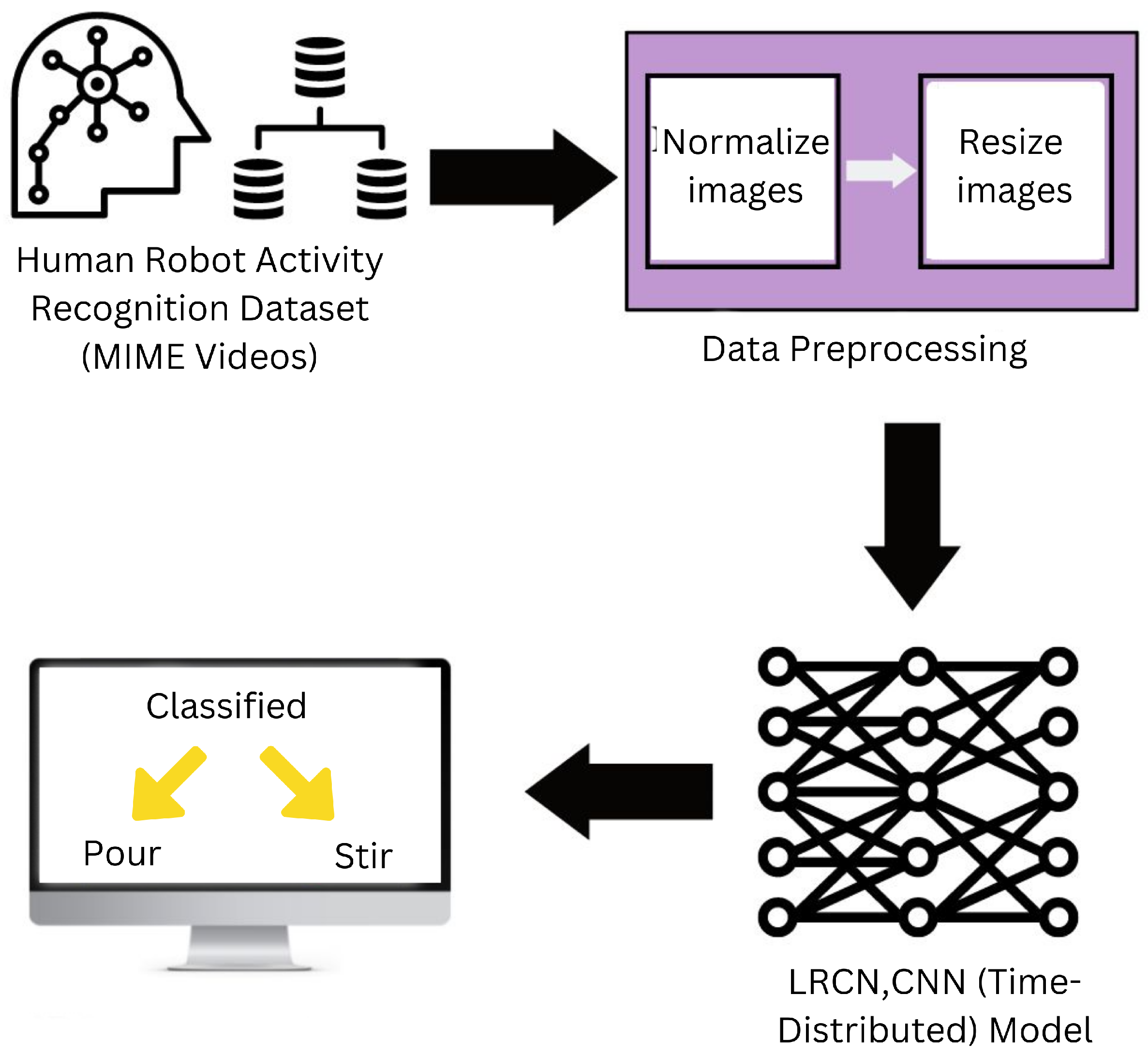

3. Proposed Methods and Descriptions

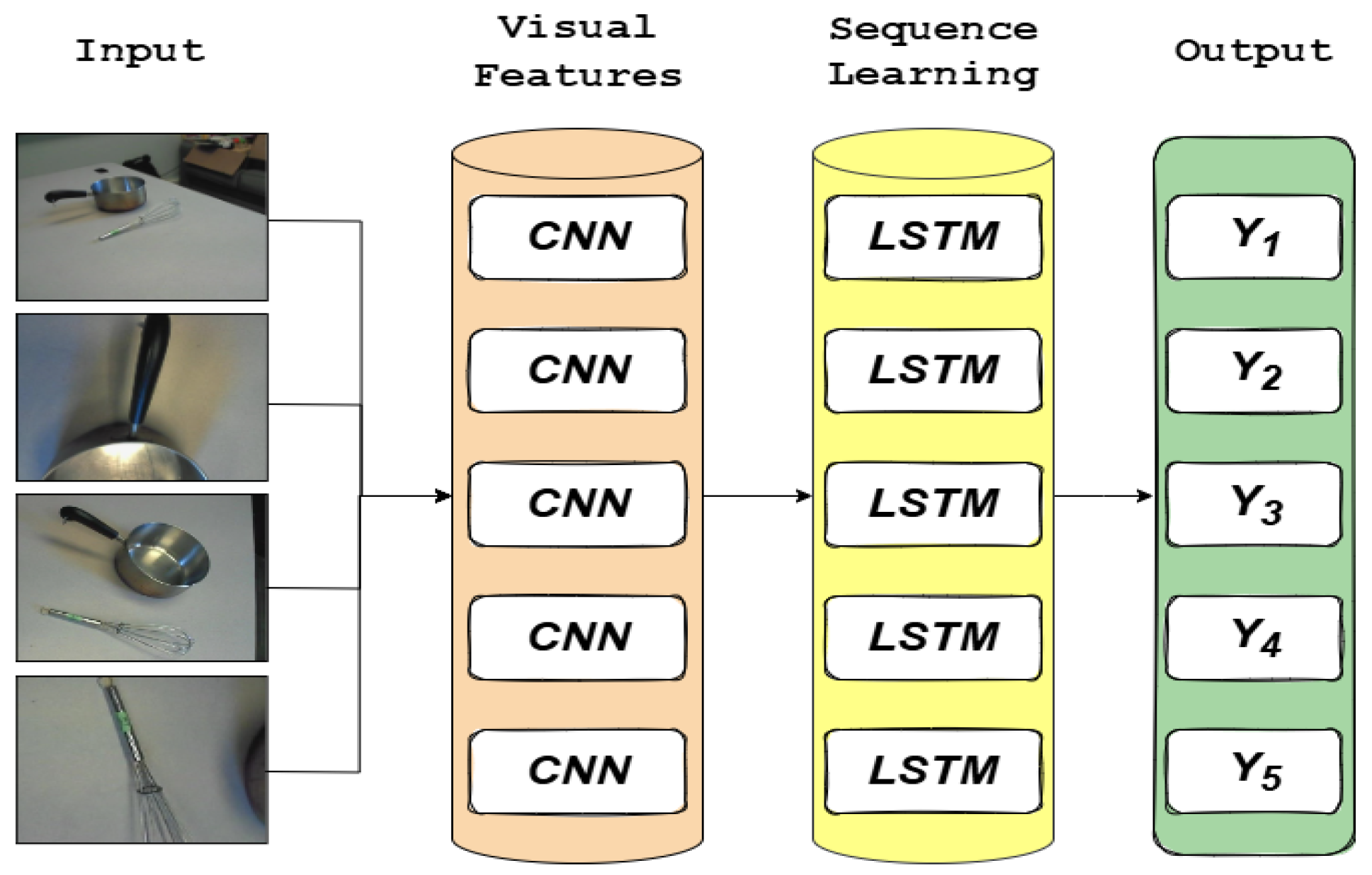

3.1. Long-Term Recurrent Convolutional Networks (LRCN)

- Forget Gate: This gate decides which data from the earlier states will be removed from the cell memory. This is computed using Equation (7).

- Cell Memory: The vital information from previous states is stored within the cell memory to prevent data loss due to diminishing gradients. Each LSTM cell continually updates the cell memory using Equation (8), wherein denote the current memory state, previous memory state, output of the forget gate, output of the input gate, and output of the candidate layer, respectively.

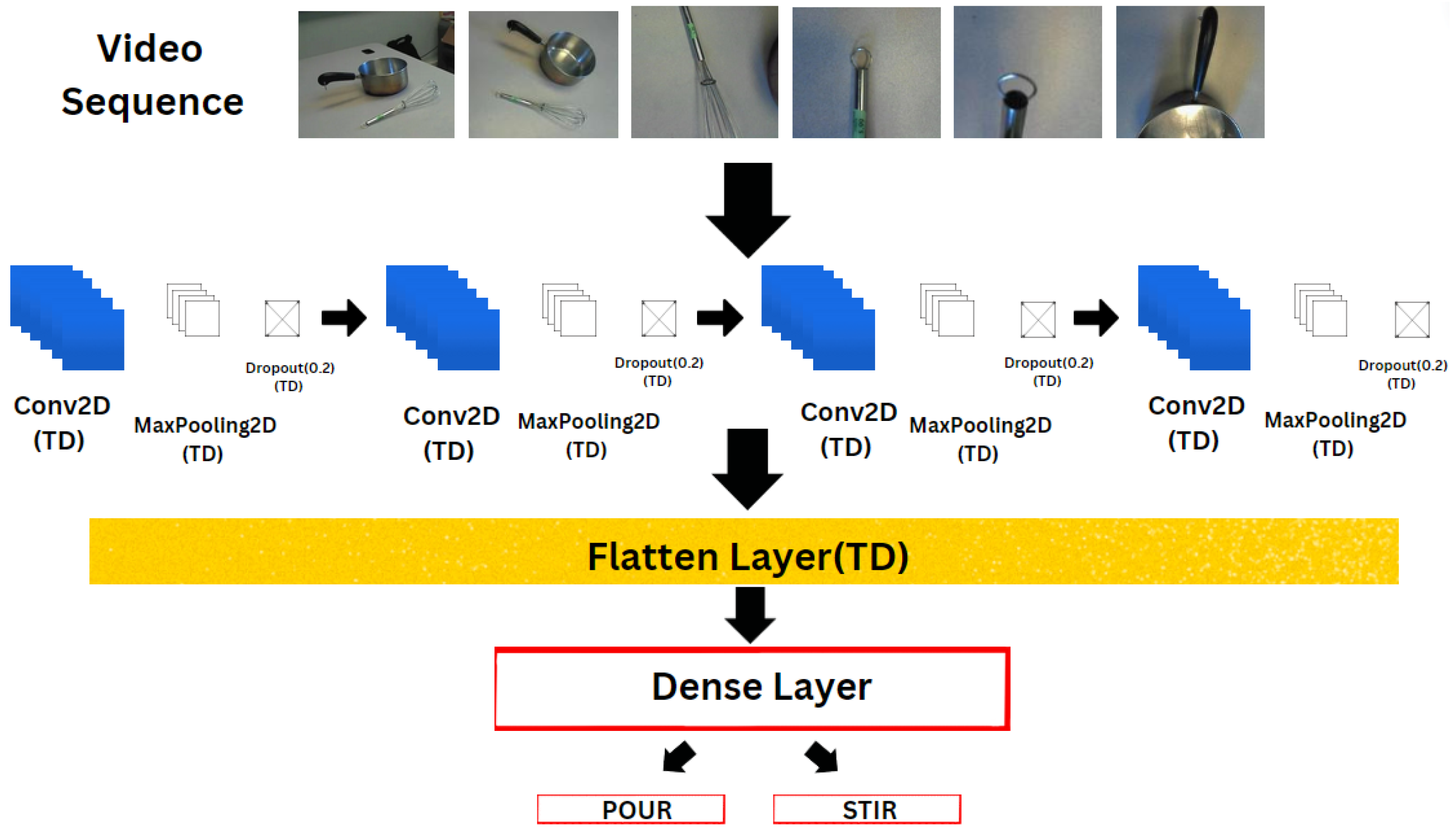

3.2. CNN-TD

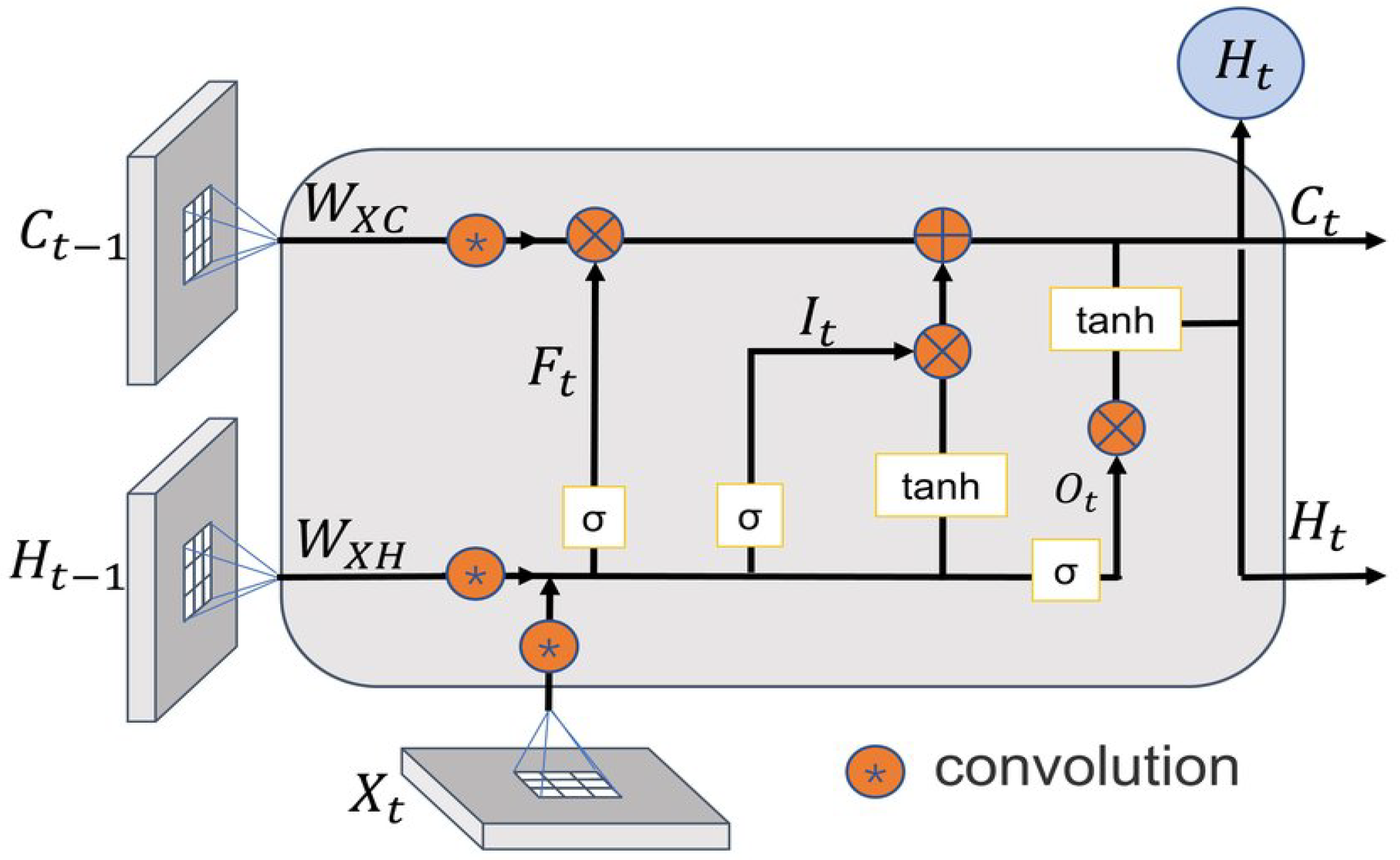

3.3. ConvLSTM (CNN-3D)

3.4. Model Architecture and Hyperparameters

4. Results

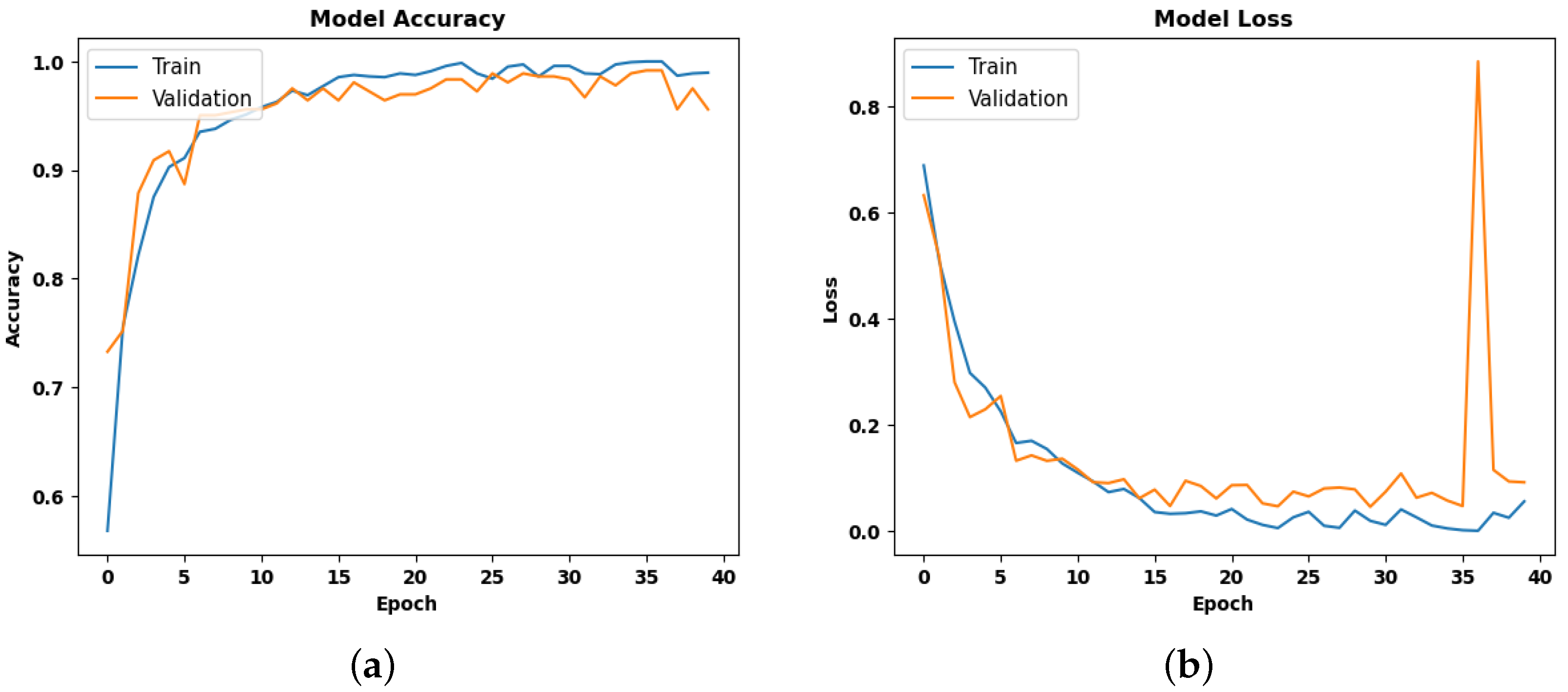

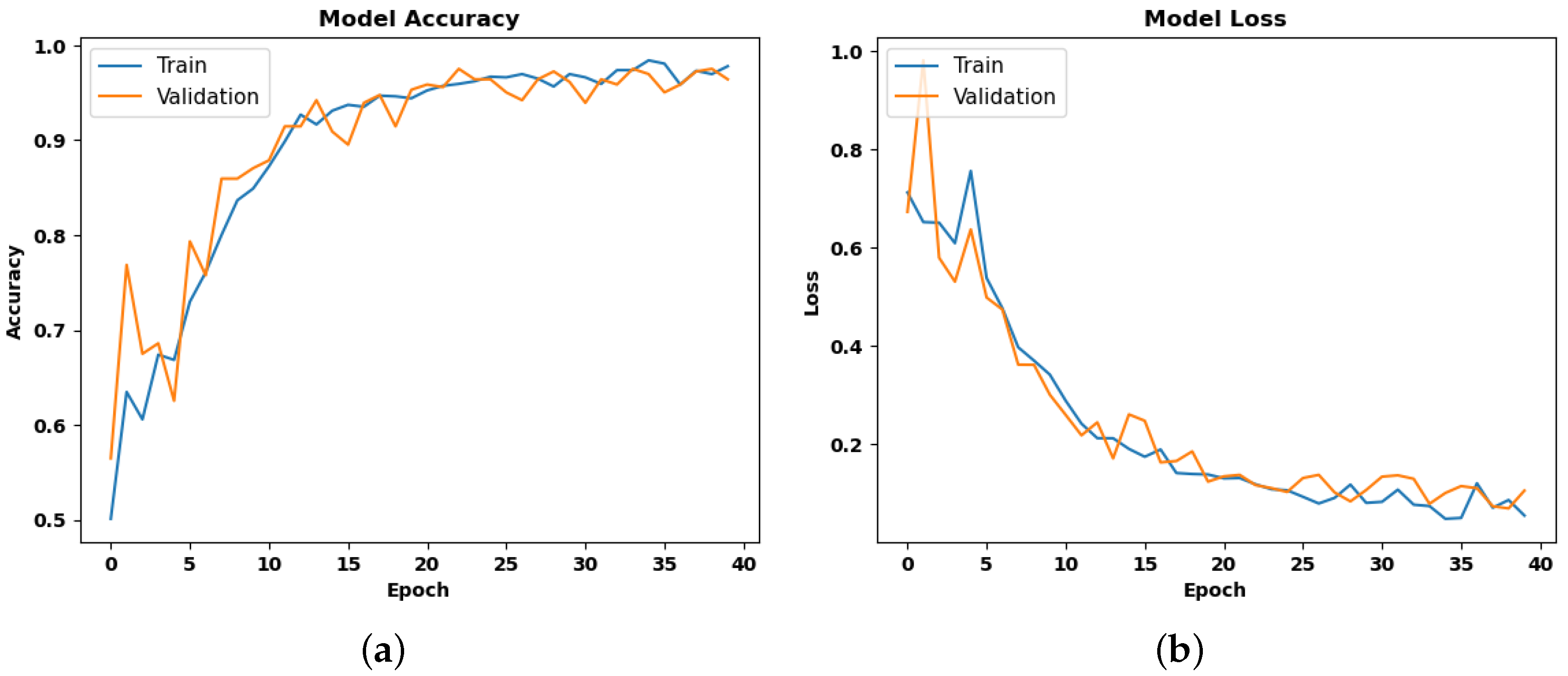

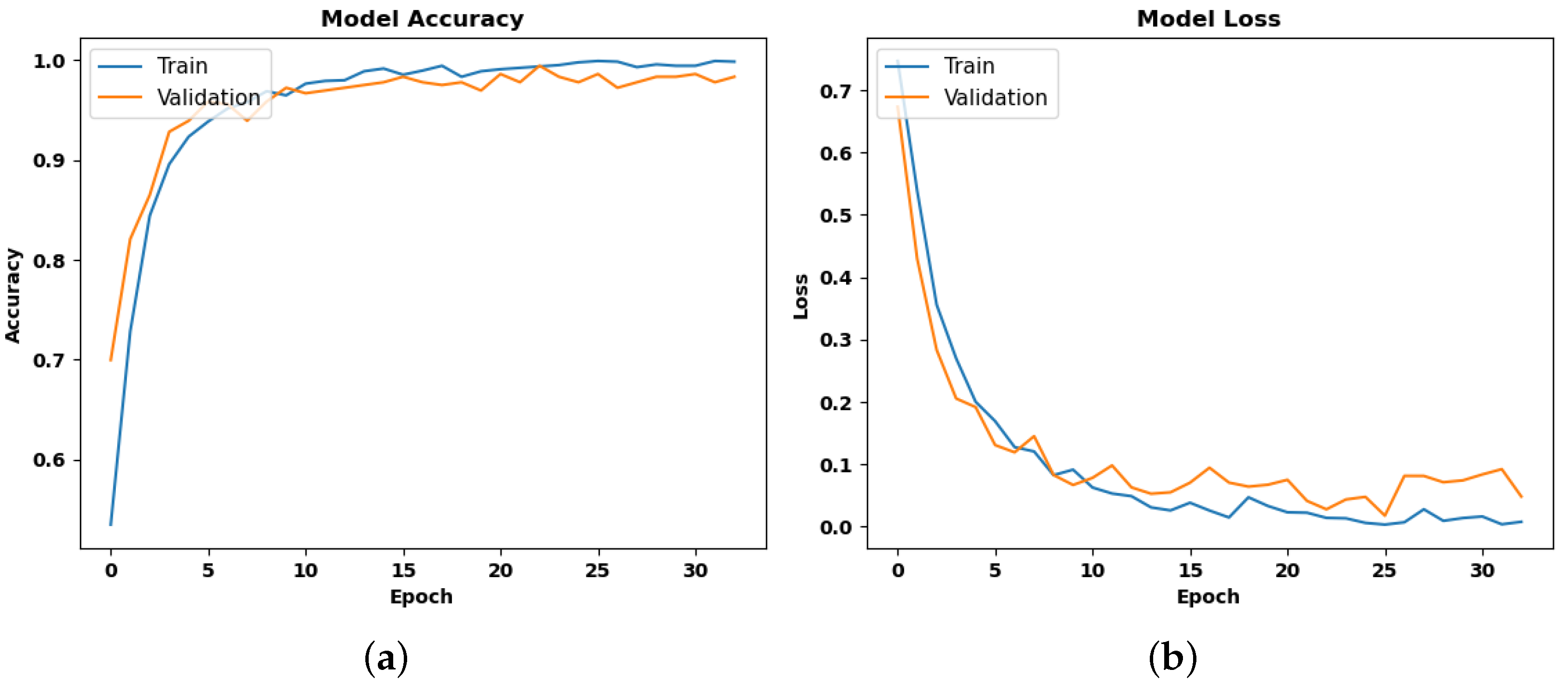

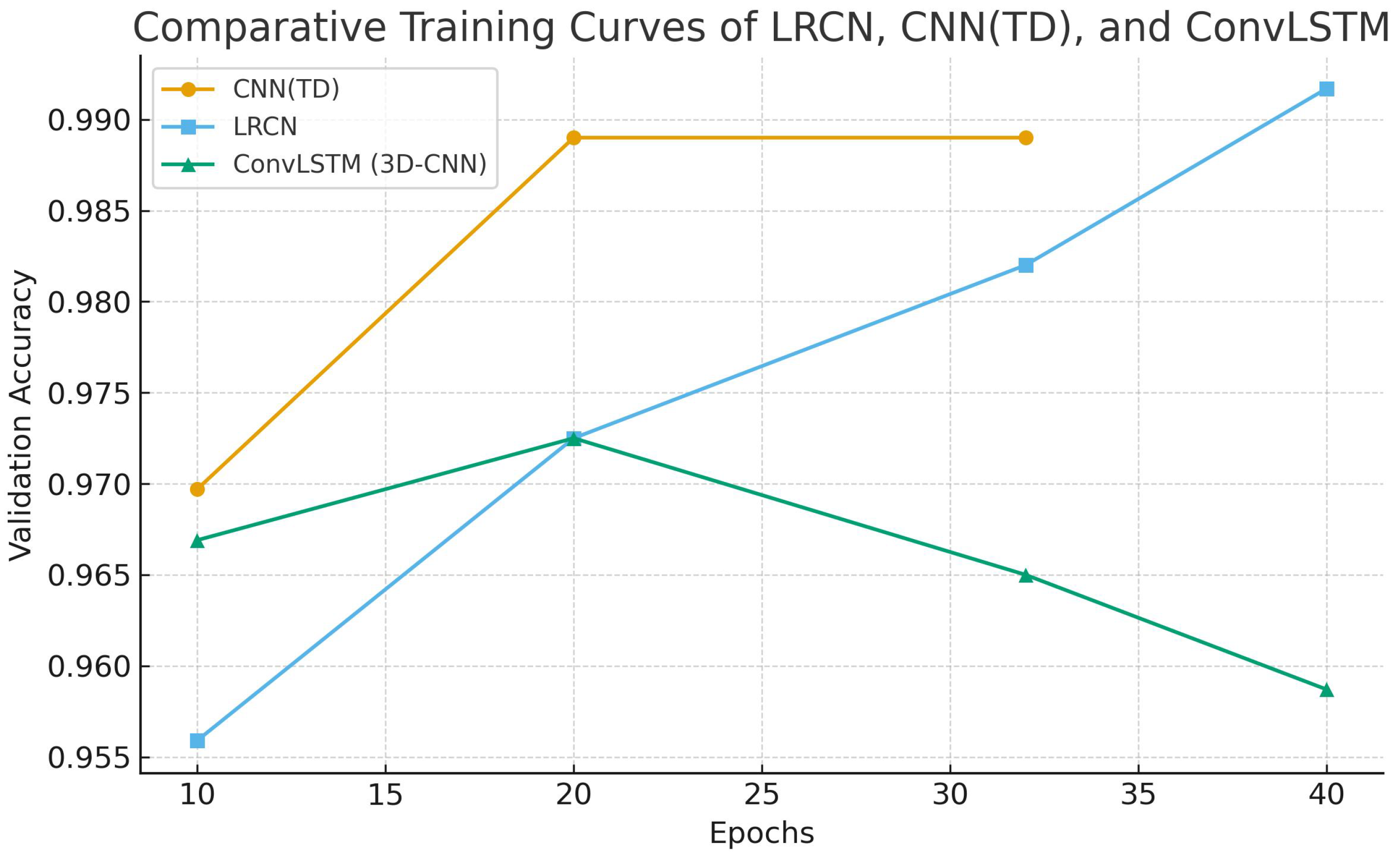

4.1. Training Performance

4.2. Testing Performance

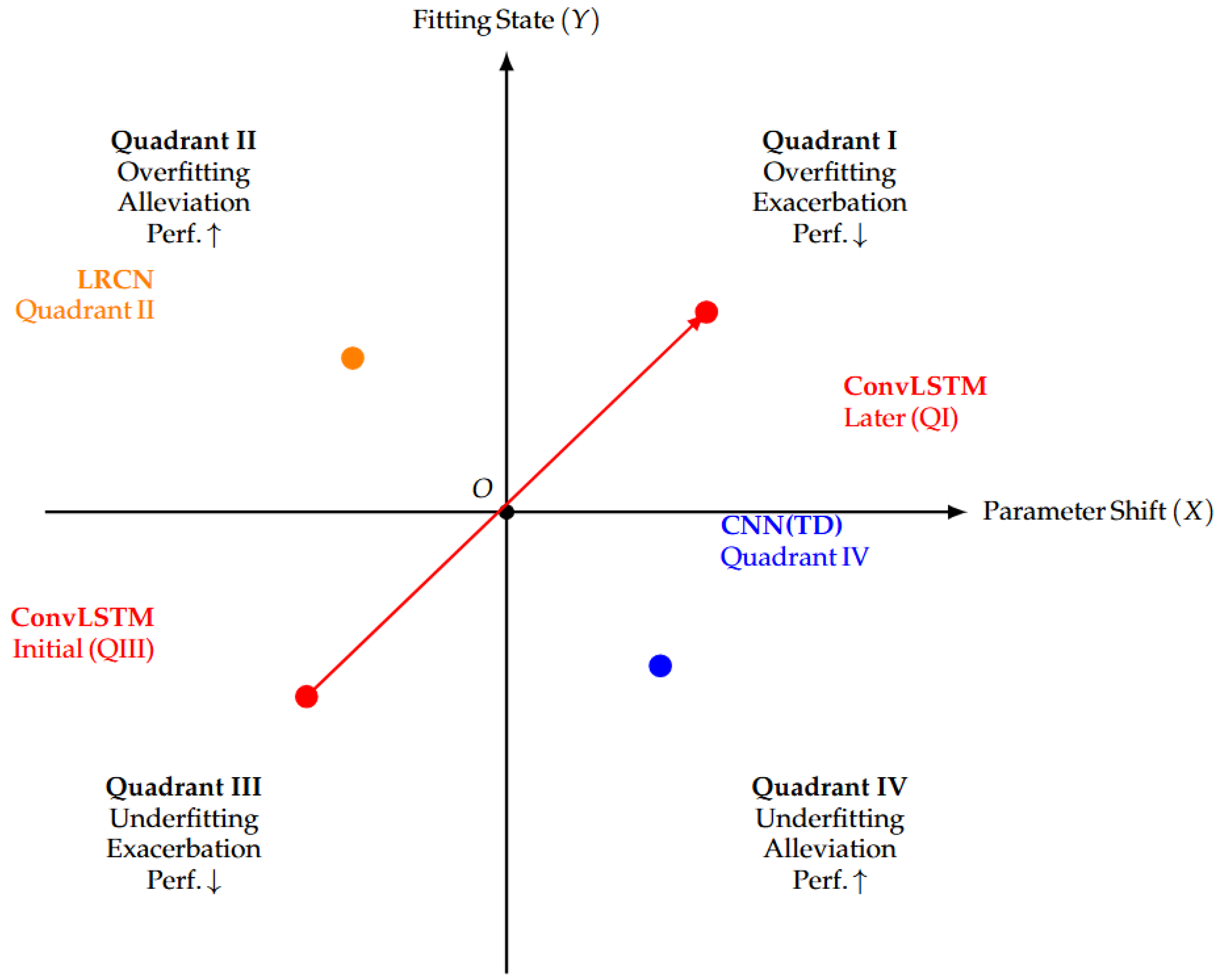

4.3. Experimental Analysis

4.4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y.W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 2006, 18, 1527–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpathy, A.; Toderici, G.; Shetty, S.; Leung, T.; Sukthankar, R.; Fei-Fei, L. Large-scale video classification with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2014), Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 1725–1732. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Two-stream convolutional networks for action recognition in videos. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2014), Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; pp. 568–576. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrish, A.; Majumder, N.; Bharadwaj, R.; Mihalcea, R.; Poria, S. A review of deep learning techniques for speech processing. Inf. Fusion 2023, 99, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.T.T.; Huynh, Q.T.; Kim, K.; Nguyen, V.Q. A Survey on Video Big Data Analytics: Architecture, Technologies, and Open Research Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xiang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ye, W.; Zhang, J. A survey of ai-generated video evaluation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.19884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansal, S.; Jha, S.; Samal, P. DL-DARE: Deep learning-based different activity recognition for the human–robot interaction environment. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 12029–12037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, W.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; Han, X. Human Activity Recognition Based on a Modified Capsule Network. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2023, 2023, 8273546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.A.; Talukder, M.A.; Uzzaman, M.S.; Debnath, C.; Chanda, M.; Paul, S.; Islam, M.M.; Khraisat, A.; Alazab, A.; Aryal, S. Deep learning-based human activity recognition using CNN, ConvLSTM, and LRCN. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 2024, 5, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, J.; Hendricks, L.A.; Guadarrama, S.; Rohrbach, M.; Venugopalan, S.; Saenko, K.; Darrell, T. Long-term Recurrent Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition and Description. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 2625–2634. [Google Scholar]

- Ljajic, A. Deep Learning-Based Body Action Classification and Ergonomic Assessment. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W.; Kang, H.S. Three-stage deep learning framework for video surveillance. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshidomi, T.; Kume, S.; Aizawa, H.; Furui, A. Classification of Carotid Plaque with Jellyfish Sign Through Convolutional and Recurrent Neural Networks Utilizing Plaque Surface Edges. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.18919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulalan, V. Deep Learning Based Methods for Improving Object Detection, Classification and Tracking in Video Surveillance. Ph.D. Thesis, Anna University, Chennai, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tabassum, I. A Hybrid Deep-Learning Approach for Multi-Class Cyberbullying Classification of Cyberbullying Using Social Medias’ Multi-Modal Data. Master’s Thesis, University of South-Eastern Norway, Notodden, Norway, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Mistry, D.; Kamal, R.; Ganguly, S.; Chakraborty, S. Facemask and Hand Gloves Detection Using Hybrid Deep Learning Model. In Smart Medical Imaging for Diagnosis and Treatment Planning; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 176–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J.; Sun, W.; Fang, Y.; Ye, N.; Yang, S.; Wu, J. A Model for Detecting Abnormal Elevator Passenger Behavior Based on Video Classification. Electronics 2024, 13, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, E.S.; Yuniarno, E.M.; Purnama, I.K.E.; Purnomo, M.H. Human activity classification using deep learning based on 3D motion feature. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2023, 12, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmi, A.M.; Al-qaness, M.A.; Dahou, A.; Abd Elaziz, M. Human activity recognition using marine predators algorithm with deep learning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 142, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Nooruddin, S.; Karray, F.; Muhammad, G. Multi-level feature fusion for multimodal human activity recognition in Internet of Healthcare Things. Inf. Fusion 2023, 94, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, S.; García-Nieto, J.; Popov, A.; Navas-Delgado, I. Human Activity Recognition From Sensorised Patient’s Data in Healthcare: A Streaming Deep Learning-Based Approach. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2023, 8, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, D. Video processing using deep learning techniques: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 139489–139507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savran Kızıltepe, R.; Gan, J.Q.; Escobar, J.J. A novel keyframe extraction method for video classification using deep neural networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 35, 24513–24524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, K.J.; Soni, A. Video classification using 3D convolutional neural network. In Advancements in Security and Privacy Initiatives for Multimedia Images; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. A sports training video classification model based on deep learning. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, 7252896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentyala, S.; Dowsley, R.; De Cock, M. Privacy-preserving video classification with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8487–8499. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, A.; Belhaouari, S.B. Deep Learning for Video Classification: A Review. TechRxiv 2021, 1, 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.P.; Tan, J.; Shun-Shin, M.J.; Mahdi, D.; Nowbar, A.N.; Arnold, A.D.; Ahmad, Y.; McCartney, P.; Zolgharni, M.; Linton, N.W.; et al. Improving ultrasound video classification: An evaluation of novel deep learning methods in echocardiography. J. Med. Artif. Intell. 2020, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, D.; Tang, X.; Gool, L.V. Temporal Segment Networks: Towards Good Practices for Deep Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9912, pp. 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, G. Big data and deep learning-based video classification model for sports. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 1140611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, T.; Dubey, S. Prediction of diseased rice plant using video processing and LSTM-simple recurrent neural network with comparative study. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 29267–29298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kwong, S.; Xu, L.; Zhao, T. Advances in Deep-Learning-Based Sensing, Imaging, and Video Processing. Sensors 2022, 22, 6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, T.; Sogi, N.; Niinuma, K.; Fukui, K. Visually explaining 3D-CNN predictions for video classification with an adaptive occlusion sensitivity analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2–7 January 2023; pp. 1513–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, D.E.; Kulhare, S.; Millin, R.; Laverriere, Z.; Mehanian, C.; Delahunt, C.B.; Banik, D.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, M.; Ji, Y.; et al. Deep Learning Video Classification of Lung Ultrasound Features Associated with Pneumonia. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 3102–3111. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, M.; Mahesh, K. Sports Video Classification Framework Using Enhanced Threshold-Based Keyframe Selection Algorithm and Customized CNN on UCF101 and Sports1-M Dataset. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 3218431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Ding, L.; Wu, S.; Ren, B.; Sebe, N.; Rota, P. Deep unsupervised key frame extraction for efficient video classification. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2023, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnusdei, G.P.; Elia, V.; Gnoni, M.G. A classification proposal of digital twin applications in the safety domain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 154, 107137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cameron, I.; Hassall, M. Improving process safety: What roles for Digitalization and Industry 4.0? Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 132, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, R. Hand hygiene video classification based on deep learning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.08127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelliah, B.J.; Harshitha, K.; Pandey, S. Adaptive and effective spatio-temporal modelling for offensive video classification using deep neural network. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Inform. 2023, 11, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cryer, S.; Acharya, L.; Raymond, J. Video and image classification using atomisation spray image patterns and deep learning. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 200, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sabzi, S.; Pourdarbani, R.; Kalantari, D.; Panagopoulos, T. Designing a fruit identification algorithm in orchard conditions to develop robots using video processing and majority voting based on hybrid artificial neural network. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Y.; Chen, L.; Zahiri, M.; Balaraju, N.; Patil, S.; Mehanian, C.; Gregory, C.; Gregory, K.; Raju, B.; Kruecker, J.; et al. Weakly Semi-Supervised Detector-Based Video Classification with Temporal Context for Lung Ultrasound. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 2483–2492. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, R.; Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yang, M.H.; Belongie, S.; Cui, Y. Multimodal open-vocabulary video classification via pre-trained vision and language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.07646. [Google Scholar]

- Kansal, S.; Kansal, P. Robotic Hand Pour & Stir Video Dataset. 2023. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/8baa9574ce5ae310af601d342765670b61246e37140a6d190270f4601424a058 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Soomro, K.; Zamir, A.R.; Shah, M. UCF101: A dataset of 101 human actions classes from videos in the wild. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1212.0402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehne, H.; Jhuang, H.; Garrote, E.; Poggio, T.; Serre, T. HMDB: A large video database for human motion recognition. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2011), Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 2556–2563. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G.E. Rectified Linear Units Improve Restricted Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Haifa, Israel, 21–24 June 2010; pp. 807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.Y.; Wong, W.K.; Woo, W.C. Convolutional LSTM network: A machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2015), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 201; pp. 802–810.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Q.; Wang, X.; Lei, L.; Song, Y. Dynamic bound adaptive gradient methods with belief in observed gradients. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 168, 111819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Wang, X.; Lai, J.; Lei, L.; Song, Y.; He, J.; Li, R. Quadruplet depth-wise separable fusion convolution neural network for ballistic target recognition with limited samples. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 235, 121182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradski, G. The OpenCV Library. Dr. Dobb’S J. Softw. Tools 2000. Available online: https://jacobfilipp.com/DrDobbs/articles/DDJ/2000/0011/0011k/0011k.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October; pp. 618–626.

| Sr. No. | Model | Epoch | Validation Loss | Validation Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LRCN | 10 | 0.1314 | 0.9559 |

| 20 | 0.0920 | 0.9725 | ||

| 40 (Last) | 0.0403 | 0.9917 | ||

| 2 | CNN-TD | 10 | 0.0806 | 0.9697 |

| 20 | 0.0395 | 0.9890 | ||

| 32 (Early Stop) | 0.0533 | 0.9890 | ||

| 3 | ConvLSTM (3D-CNN) | 10 | 0.1217 | 0.9669 |

| 20 | 0.1766 | 0.9725 | ||

| 40 (Last) | 0.2345 | 0.9587 |

| No. | Model | Loss | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LRCN | 0.0574 | 0.9868 | 0.978 | 0.975 | 0.975 |

| 2 | CNN-TD | 0.0236 | 0.9868 | 0.982 | 0.982 | 0.981 |

| 3 | ConvLSTM | 0.1236 | 0.9736 | 0.967 | 0.965 | 0.965 |

| Optimizer | Best Val. Acc. | Epoch@Best | Final Val. Loss | Final Val. Acc. | Test Acc. | Test Loss | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adam | 0.9890 | 32 | 0.0533 | 0.9890 | 0.9868 | 0.0412 | 18.2 |

| AdaBoB | 0.9915 | 28 | 0.0487 | 0.9908 | 0.9879 | 0.0398 | 18.0 |

| Category | Specification |

|---|---|

| Hardware Configuration | CPU: Intel Core i7-5600 (6 cores @ 3.2 GHz); RAM: 16 GB; |

| GPU: fixed 16 GB configuration (used across all models). | |

| Software Environment | Python 3.x; TensorFlow (TF–Keras backend); Keras layers (Conv2D, MaxPooling2D, |

| LSTM, ConvLSTM2D, TimeDistributed, Dropout); OpenCV [56] for video preprocessing. | |

| Dataset Parameters | Total videos: 2000 (Pour: 1000; Stir: 1000 after balancing); |

| Frame size: 224 × 224 pixels; FPS: 30; sequence length: 30 frames/video; | |

| dataset split: 64% training, 16% validation, 20% testing. | |

| Common Training Settings | Optimizer: Adam [51]; learning rate: ; , , ; |

| batch size: 16; epochs: 40 (CNN-TD early-stopped at 32); | |

| loss function: categorical cross-entropy. | |

| LRCN Configuration | Backbone: VGG16 pre-trained on ImageNet (first 10 conv layers frozen, last 5 fine-tuned); |

| LSTM: 256 units; dropout: 0.5; dense: 64 units + softmax (3 classes); | |

| ensemble: 5 seeds (0, 7, 21, 37, 45) with majority voting. | |

| CNN-TD Configuration | Conv2D filters: 64, 128, 256 (kernel size 3 × 3); maxpooling: 2 × 2; |

| dropout: 0.2; TimeDistributed wrapper applied to CNN layers. | |

| ConvLSTM Configuration | ConvLSTM2D: 64 filters, 3 × 3 kernel; ReLU activation; dropout: 0.1; |

| preserved spatial–temporal structure via 3D convolutional gating. | |

| Inference Metrics | Real-time throughput: CNN-TD = 18 FPS; LRCN = 13 FPS; ConvLSTM = 10 FPS; |

| CPU memory usage: LRCN = 2.3–2.7 GB; CNN-TD = 3.0–3.5 GB; ConvLSTM = 2.5–3.2 GB. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Singla, S.; Singla, S.; Singla, K.; Kansal, P.; Kansal, S.; Bishnoi, A.; Narayan, J. NovAc-DL: Novel Activity Recognition Based on Deep Learning in the Real-Time Environment. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2026, 10, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010011

Singla S, Singla S, Singla K, Kansal P, Kansal S, Bishnoi A, Narayan J. NovAc-DL: Novel Activity Recognition Based on Deep Learning in the Real-Time Environment. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2026; 10(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingla, Saksham, Sheral Singla, Karan Singla, Priya Kansal, Sachin Kansal, Alka Bishnoi, and Jyotindra Narayan. 2026. "NovAc-DL: Novel Activity Recognition Based on Deep Learning in the Real-Time Environment" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 10, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010011

APA StyleSingla, S., Singla, S., Singla, K., Kansal, P., Kansal, S., Bishnoi, A., & Narayan, J. (2026). NovAc-DL: Novel Activity Recognition Based on Deep Learning in the Real-Time Environment. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 10(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010011