1. Introduction

In modern cryptographic systems, the identification of the cryptographic algorithms plays a pivotal role in cryptographic analysis [

1,

2]. When plaintext is inaccessible, an adversary typically begins by inferring the cryptographic algorithms underlying the intercepted ciphertext [

3,

4,

5] (e.g., AES, DES, RSA). Once the algorithm is successfully identified, the attacker can launch targeted cryptanalysis by selecting optimized key-recovery strategies, tailoring algebraic or statistical attacks, or leveraging structural vulnerabilities, thereby substantially reducing both the complexity and computational cost of decryption. As a result, cryptographic algorithm identification serves as a practical and highly valuable capability in real-world cryptanalysis and network offense scenarios.

The rapid progress in artificial intelligence in recent years has emerged as a key enabler for cryptographic algorithm identification. Specifically, machine learning-based schemes have shown considerable success in identifying various international standard ciphers [

6,

7]. In such approaches, ciphertexts are first transformed into discriminative statistical representations before being fed into learning models. A common and effective practice is to extract statistical features (e.g., the NIST-15 features) based on the NIST SP 800-22 statistical test suite [

8], which quantifies the degree of randomness and structural regularity within ciphertext sequences. The NIST-15 features such as Frequency Test and Runs Test capture distinct statistical behaviors exhibited by different cryptographic algorithms, due to their internal diffusion and substitution structures. By converting ciphertexts into numerical vectors through these statistical indicators, supervised classifiers (e.g., Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, or Deep Neural Networks) can be trained to automatically learn the mapping between feature distributions and algorithms. Therefore, this method essentially addresses a multi-class classification problem in machine learning, where each class corresponds to a cryptographic algorithm. For illustration,

Figure 1 depicts that legitimate parties Alice and Bob encrypt/decrypt plaintext via a pre-negotiated cipher and key, while adversary Eve passively intercepts the ciphertext and infers its underlying cryptographic algorithm to leverage algorithm-specific vulnerabilities or optimized key recovery. To this end, Eve trains a deep neural network (DNN) with ciphertext samples from known algorithms to automatically predict the type of cryptographic algorithm used in the intercepted ciphertext. Up to now, DNNs have demonstrated promising performance in cryptographic algorithm identification, thus emerging as the mainstream choice.

In this paper, we for the first time apply adversarial example techniques to counter cryptographic algorithm identification. Specifically, we generate adversarial ciphertexts by applying controlled, reversible bit-level perturbations that are designed to mislead cryptographic algorithm-identification models without compromising legitimate decryption. This approach acts as a defense mechanism to enhance ciphertext unidentifiability. For illustration,

Figure 2 depicts that before transmission, the sender imposes the perturbations on her ciphertext, which the receiver removes prior to normal decryption. The adversary intercepts the perturbed ciphertext but fails to infer the type of the cryptographic algorithm, since the statistical characteristics of the ciphertext have been modified to mislead the DNN-based identification model. However, the receiver can correctly decrypt the ciphertext, after removing the perturbations according to the perturbing method he knows. Compared with traditional countermeasures (multi-layer encryption, algorithm obfuscation, protocol camouflage), this approach is simpler and more practical: it acts directly on ciphertexts without modifying algorithms/keys management.

In our method, we implement adversarial perturbations on ciphertexts via bit flipping. Our method employs two strategies to mislead the target classifier: (1) making each class resemble another specific class (i.e., the mimic class) via bit flipping, thereby increasing discrimination difficulty; (2) altering the inherent features of each class through bit flipping, making it less like itself. The key lies in selecting the bit positions for flipping. To reduce implementation complexity, we choose the same bit positions for ciphertexts encrypted with the same algorithm (i.e., class). Hence our method is called the Class-Specific Perturbation Mask Generation algorithm (CSPM), which uses a mask to indicate the bit positions for flipping in the ciphertext. To generate such masks, CSPM first trains a deep neural network to emulate the adversary’s identification model (called the substitute model). By interacting with the substitute model (i.e., perturbing the ciphertext and sending the results to the substitute model for classification), CSPM scores each bit position, determines the mask based on these scores, and selects the bits with the highest scores for flipping. We conduct extensive experiments to evaluate CSPM across multiple cipher families using the NIST-15 statistical suite as the feature extraction backbone. The results demonstrate that CSPM achieves a substantial degradation of identification accuracy in all valid feature–cipher combinations: the accuracy decline consistently exceeds 25%, reaching up to 35.72% in the best case. Moreover, CSPM requires flipping only a small fraction of the ciphertext bits while preserving the underlying cryptographic scheme and keying process, thereby offering a stealthy and practical defense. The main contributions of this work are summarized below:

We propose a class-level adversarial perturbation framework that defeats cryptographic algorithm identification without modifying the encryption scheme or key infrastructure. As we know, our method is the first to resist cryptographic algorithm identification with adversarial perturbations.

Our study indicates that the key to resisting cryptographic algorithm identification lies in the selection of bit positions to flip, rather than the number of flipped bits. Our method determines the flipped bit positions based on two criteria: reducing inter-class distance and altering the class’s own characteristics. This provides a design reference and performance comparison baseline for similar studies.

We conduct extensive evaluation across multiple cryptographic algorithms and NIST-15 statistical features, achieving over 25% accuracy reduction under all settings, demonstrating the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed method.

2. Preliminary

2.1. Cryptographic Randomness Testing Metrics

Randomness testing of ciphertext is a critical approach to evaluating the security of cryptographic systems. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) [

8] defines 15 randomness testing methods in SP 800-22 to comprehensively assess the global and local randomness properties of binary sequences. These tests effectively determine whether a sequence exhibits statistical characteristics consistent with true randomness. Below is a detailed description of the 15 NIST randomness tests, presented in the original order:

(1) Cumulative Sums Test: examines whether the partial sums of the sequence significantly deviate from the expected value. Excessively large or small sums suggest non-randomness.

(2) Linear Complexity Test: uses the Berlekamp-Massey [

9,

10] algorithm to compute the linear complexity of the sequence and compares it to the expected complexity of a true random sequence. Significant deviations indicate potential non-randomness.

(3) Longest Run of Ones Test: assesses whether the length of the longest run of consecutive 1 s in the sequence aligns with the expected distribution of a true random sequence. Excessively long or short runs may indicate non-randomness.

(4) Overlapping Template Matching Test: counts the occurrences of specific overlapping patterns of consecutive 1 s in the sequence and compares them to the expected distribution in a true random sequence. Large deviations suggest non-randomness.

(5) Random Excursions Test: evaluates whether the number of visits to specific states (e.g., cumulative sums) in the sequence significantly deviates from the expected behavior in a true random sequence. Large deviations indicate potential non-randomness.

(6) Random Excursions Variant Test: assesses whether the frequency of specific states in a random walk deviates significantly from the expected behavior in a true random sequence. Significant deviations suggest non-randomness.

(7) Approximate Entropy Test: compares the frequency of m-bit and (m + 1)-bit subsequences in the sequence and evaluates deviations from the expected distribution of a true random sequence to determine randomness.

(8) Maurer’s Universal Statistical Test: determines whether the sequence can be significantly compressed. A sequence that resists compression is typically considered random.

(9) Discrete Fourier Transform Test: analyzes the periodicity of the sequence through its frequency spectrum and compares it to that of a true random sequence. Significant deviations in periodicity indicate potential non-randomness.

(10) Serial Test: examines whether the frequency of all m-bit subsequences in the sequence is consistent with that of a true random sequence. Uneven frequency distributions may indicate non-randomness.

(11) Binary Matrix Rank Test: constructs matrices from the sequence and evaluates the linear dependence of fixed-length subsequences. Strong linear dependence suggests non-randomness.

(12) Non-overlapping Template Matching Test: counts the occurrences of specific non-overlapping patterns in the sequence and compares them to the expected distribution in a true random sequence. Large deviations suggest non-randomness.

(13) Block Frequency Test: divides the sequence into non-overlapping M-bit blocks and checks whether the distribution of 0 s and 1 s within each block is consistent with randomness. Significant deviations suggest non-randomness.

(14) Frequency Test: examines whether the proportion of 0 s and 1 s in a binary sequence is approximately equal, as expected in an ideal random sequence.

(15) Runs Test: evaluates whether the distribution of runs (consecutive sequences of identical bits) in the sequence aligns with the expected distribution of a random sequence. Anomalous run distributions may indicate non-randomness.

2.2. Adversarial Examples

Adversarial examples are inputs generated by intentionally adding small perturbations [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Such inputs are perceptually indistinguishable from legitimate inputs to humans, yet they can mislead machine learning models. Based on the attacker’s knowledge of the target model, adversarial attacks can be categorized into three types: in white-box attacks, attackers have full knowledge of the target model [

11,

12,

13,

14]; in gray-box attacks, attackers have only partial knowledge of the model [

15,

16,

17]; and in black-box attacks, attackers have no knowledge of the model at all [

18,

19,

20]. Currently, research on adversarial examples has extended to numerous fields [

21,

22,

23,

24]. For instance, in the field of Android malware detection [

21,

22,

23], attackers generate adversarial applications by modifying features such as permissions and API calls, evading detection while retaining malicious functionality.

3. Problem Definition and Threat Model

3.1. Problem Definition

In a typical secure communication scenario, let Alice be the sender and Bob be the legitimate receiver. Alice encrypts a plaintext p to a ciphertext c using a cryptographic algorithm with secret key k, obtaining a ciphertext sequence , where denotes a binary of length n. The ciphertext is transmitted over an open channel to Bob, who can recover the plaintext by applying the corresponding decryption algorithm . However, an adversary, Eve, intercepts the ciphertext during transmission. Although Eve cannot directly decrypt c without the key, she possesses a deep neural network classifier trained on ciphertext samples from multiple cryptographic algorithms . By extracting statistical or structural features from the ciphertext and inputting them into the classifier, Eve can predict the most likely cryptographic algorithms as . Once the cryptographic algorithm is identified, Eve can apply targeted cryptanalysis or side-channel attacks to recover the plaintext more efficiently.

To defend against such model-based ciphertext identification, we propose to introduce an adversarial perturbation in the ciphertext level. Specifically, given an original ciphertext , we define an adversarial perturbation mask , which flips a subset of bits according to the rule , where ⊕ denotes the bitwise XOR operation. The perturbed ciphertext should preserve decryptability for Bob—since Bob, knowing m, can simply recover the original ciphertext as before decryption—but it should simultaneously mislead Eve’s classifier so that outputs an incorrect cryptographic algorithm label. Formally, the defense objective is to find an optimal perturbation mask that minimizes the classifier’s confidence on the true algorithm label while maintaining ciphertext reversibility for legitimate communication. In this setting, the adversarial perturbation acts as a protective layer on top of the ciphertext, directly deceiving model-based algorithm identification and thereby strengthening the robustness of cryptographic systems against attacks.

3.2. Threat Model

We consider a realistic ciphertext interception scenario where an adversary, Eve, passively eavesdrops on the communication channel between Alice and Bob. Eve can collect a large number of ciphertext samples encrypted by different algorithms , but she does not have access to the corresponding plaintexts or secret keys. Instead of attempting direct decryption, Eve employs a trained deep neural network classifier to infer the underlying cryptographic algorithms used for each ciphertext. This classifier takes as input a set of statistical or transformed features extracted from the ciphertext sequence , and outputs a predicted algorithm label . The goal of Eve is to correctly identify the cryptographic algorithms, which significantly reduces the search space for subsequent cryptanalytic attacks.

We assume that Eve’s classifier is trained offline on a large-scale, labeled dataset of ciphertexts generated from known cryptographic algorithms, so that it generalizes effectively to unseen ciphertexts. The defenders, i.e., Alice and Bob, are aware that such model-based attackers may intercept and analyze ciphertexts; their primary objective is therefore to mislead Eve’s classifier into predicting an incorrect cryptographic-algorithm label for transmitted ciphertexts.

To counteract this threat, Alice and Bob introduce a reversible adversarial perturbation into the transmitted ciphertext, producing a perturbed ciphertext . The perturbation m is designed to satisfy two requirements: (1) Bob can efficiently recover the original ciphertext (e.g., ), and (2) the classifier is misled, i.e., , where denotes the feature extraction process used by the classifier.

This setting models a black-box attack scenario from the defender’s perspective: the defender does not have access to Eve’s classifier parameters , but can generate perturbations by observing the classifier’s predicted confidence scores or using a substitute model trained on similar data. The design objective is thus to construct an adversarial perturbation that remains effective under model uncertainty, thereby degrading the classification accuracy of cryptographic-algorithm systems while maintaining communication integrity between Alice and Bob.

4. Methodology

4.1. Overview

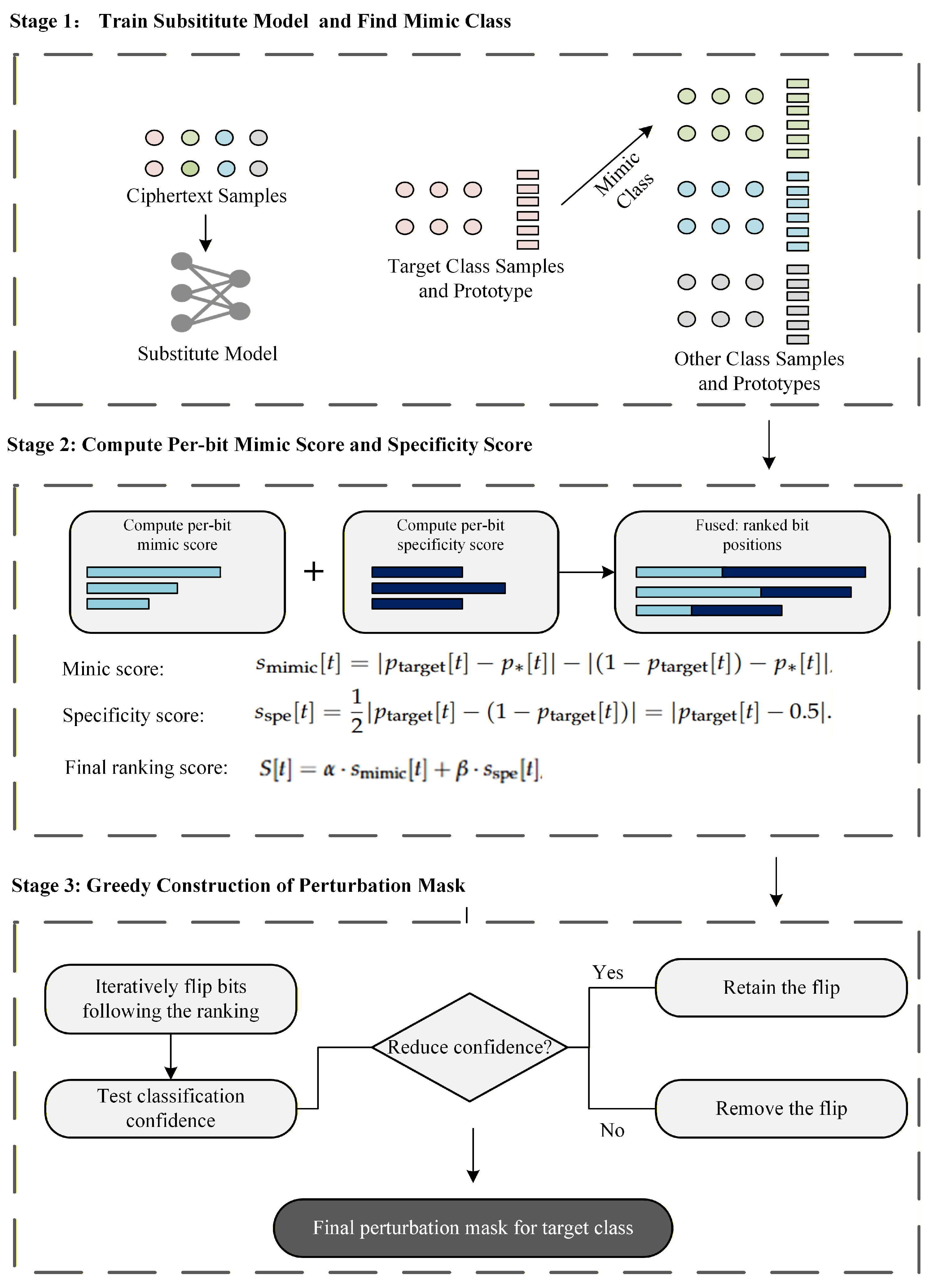

The CSPM method is designed to generate perturbation masks for binary ciphertext samples grouped into k classes, aiming to reduce the classification confidence of a pre-trained deep neural network (DNN) classifier while adhering to a perturbation budget. The perturbation mask is used to flip the chosen bits of the ciphertext with the XOR operation, thereby misleading the classifier. Instead of randomly selecting the bits to be flipped, CSPM employs the following two ideas for optimally choosing and flipping these bits.

1. Mimicry for reducing inter-class distance. This idea is to make samples of a certain class (target class) more similar to those of another class (mimic class) through bit flipping, thereby making it more difficult for the cryptographic algorithm classifier to identify them. By comparing the differences between the ciphertexts produced by different cryptographic algorithms, CSPM identifies the most similar cryptographic algorithm (i.e., mimic class) for each cryptographic algorithm (i.e., target class). It then selects the positions of the bits to be flipped based on the degree of difference between the two algorithms at each bit position. Specifically, bits at positions with greater differences are flipped first, making the modified ciphertext more similar to the one generated by the mimic cryptographic algorithm. In this way, CSPM can mislead the cryptographic algorithm classifier of the adversary.

2. Distortion for altering class features. The idea is to alter the features of samples in each class through bit flipping, thereby making it more difficult for the cryptographic algorithm classifier to identify them. In general, if bit 0 or 1 appears more frequently at certain bit positions of the ciphertext (instead of occurring randomly with equal probability), this can be regarded as a typical feature of the class (i.e., cryptographic algorithm). Hence, CSPM evaluates the randomness of the ciphertext generated by each cryptographic algorithm at every bit position, and identifies bit positions where the probability difference between the occurrence of 0 s and 1 s is significant and flips those bits. This alters the inherent features of the class, making it harder to be accurately identified by the adversary.

It is worth noting that the first step in implementing mimicry and distortion is to represent the feature of every class or cryptographic algorithm. We can use the “average” sample (referred to as the prototype) of each class to accomplish this task. In summary, we use

Figure 3 to depict our method, which operates in three stages: (1) Train substitute model and find mimic class, (2) Compute Per-bit Mimic score and specificity score, (3) Greedy construction of perturbation mask.

Formally, let denote the set of k cryptographic algorithms or classes. Each class has the same number of samples. For any class, say , its binary ciphertext samples are of length (Please note that ciphertext lengths obtained by different cryptographic algorithms for plaintexts of the same length may vary.), and split into a training subset with samples and a test subset with samples. A feature extractor maps binary ciphertext samples to a feature space, and a pre-trained DNN classifier predicts the probability that a ciphertext sample belongs to each class. Furthermore, positive weight coefficients and are introduced to balance the impacts of mimicry and distortion methods in the evaluation of bit positions. CLMP aims to produce a perturbation mask for each class that minimizes the classifier’s confidence on the target class. To achieve this goal, CLMP needs to perform the following three main steps.

4.2. Computing the Prototype for Every Class

As mentioned earlier, generating a prototype for each class is a prerequisite for mimicry and distortion. To this end, we prepare a sample subset for each class

, denoted as

, which can usually be the training subset

. For a class

, its prototype

is calculated as the average of the binary samples in

. Then, the

t-th bit of

is given by:

where

is the number of samples in

, and

is the

t-th bit of sample

c. The prototype

represents the empirical probability that bit

t is 1 in class

, providing a compact summary of the class’s bit distribution.

4.3. Evaluating Bit Positions in Misleading Classifiers

In the second step, CSPM evaluates the potential of bit positions in misleading classifiers for every class, serving as the foundation for the third step (i.e., perturbation mask generation). More specifically, CSPM analyzes each bit position according to criteria similarity and specificity respectively, and derives the score of bit positions by taking them into account.

First, CSPM identifies the mimic class, and then computes a score for each bit position based on the difference between the target class and the mimic class. The identification of mimic classes is based on the similarity between the prototypes of two classes. Note that the lengths of samples (ciphertexts) from different classes may differ. For the sake of fairness, when evaluating the similarity between the prototypes of two classes, only the minimum length of the two class prototypes is considered. For a target class

, the mimic class

is selected as the class whose prototype is most similar to

, measured by cosine similarity:

In the remainder of this paper,

is used to denote the prototype of the mimic class. Then we can use the

mimicry score to evaluate the

t-th bit position of the target class prototype. Here the mimicry score reflects the change in distance between the target and mimic prototypes when bit

t is flipped, which can be calculated as:

According to the above equation, a positive indicates that flipping bit t reduces the distance to the mimic class.

Second, CSPM computes the score of each bit position for every class, based on the probabilities of bits 0 and 1 occurring at this bit position. This score, which we refer to as

specificity score, is used to characterize the degree of difference between the occurrence probabilities of bits 0 and 1 at a certain bit position. Compared to the purely random scenario where bits 0 and 1 occur with equal probability, the greater the difference between their occurrence probabilities, the more distinct the specificity of this bit position, making this bit position easier to use for identifying the target class (i.e., cryptographic algorithm). In CSPM, the specificity score of the

t-th bit position is thus calculated as:

here,

quantifies the deviation of the target probability from the uniform distribution (0.5). It is worth noting that this metric is symmetric: a low probability (e.g.,

) yields the same specificity score as a high probability (e.g.,

). This is intentional, as both cases indicate a strong structural bias (towards 0 or 1, respectively) that distinguishes the ciphertext from random noise, whereas a value close to 0.5 implies high uncertainty and low distinguishability.

According to the above equation, a higher specificity score indicates that bit 0 or 1 appears more frequently at the corresponding bit position. This phenomenon (e.g., bit 0 or 1 appearing more frequently at certain bit positions) is likely to help adversaries identify the cryptographic algorithm.

Finally, we combine the mimicry score and specificity score to derive a final score for each bit position, which is given by:

where

and

control the trade-off between two criteria, i.e., mimicry and specificity. The purpose of this score is to comprehensively evaluate the potential of bit flipping at each position in misleading the classifier owned by the adversary, thereby providing a basis for the implementation of adversarial perturbations, as discussed in the following subsection.

4.4. Sorting Bit Positions and Generating Perturbation Masks

In the final step, CSPM sorts the bit positions for every class in descending order based on their final scores, and this order guides the subsequent bit-flipping operations to mislead the cryptographic algorithm classifier as much as possible. The main idea is described below. The CSPM will sequentially try performing bit-flipping at the corresponding positions in accordance with the aforementioned order, and observe the misleading effect of this operation on the cryptographic algorithm classifier. Once it can reduce the classifier’s confidence in the target class, the position will be retained and recorded on the perturbation mask. Otherwise, the position will be ignored by CSPM. For simplicity, we adopt a greedy strategy that iteratively performs the aforementioned operations. This process sequentially identifies and records the bit positions worthy of perturbation, finally forming a perturbation mask for every class. This perturbation mask is then used to perturb other samples of the same class, helping to protect them from being accurately identified by the classifier regarding their corresponding cryptographic algorithm type. The detailed steps are described as follows.

Let

denote the perturbation mask of the

j-th class. The mask is initialized as

. In descending order of final scores, CSPM sequentially selects bit positions, performs bit-flipping operations on all samples in the perturbation set

, and calculates the average value of the classifier’s output confidence for the target class (i.e., class

j). The average confidence is calculated with the

EvalAvgConfidence function, i.e.,

where ⊕ represents the XOR operation,

denotes the perturbed sample,

reflects the features extracted from the perturbed sample, and

is the probability predicted by the classifier that the perturbed sample belongs to class

j. For ease of understanding, we have incorporated the aforementioned process (along with the previous steps) into Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 CSPM |

Require: Binary ciphertext samples grouped into k classes , each sample of length ; - 1:

For each class : train subset with samples and test subset with samples; - 2:

Feature extractor ; pre-trained DNN classifier ; - 3:

Weight coefficients .

Ensure: perturbation mask for each class . - 4:

for to k do - 5:

- 6:

end for - 7:

for target = 1 to k do ▹ Identify mimic class - 8:

for to k, do - 9:

- 10:

end for - 11:

, ▹ Compute combined score for each bit - 12:

for to n do - 13:

- 14:

- 15:

- 16:

- 17:

- 18:

end for - 19:

- 20:

- 21:

- 22:

for idx in indices do - 23:

- 24:

- 25:

if then - 26:

- 27:

- 28:

end if - 29:

end for - 30:

Store m as the perturbation mask for class - 31:

end for

|

- 1:

function EvalAvgConfidence - 2:

- 3:

for each do - 4:

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

end for - 9:

return total/ - 10:

end function

|

5. Evaluation

In this section, we assess CSPM through the following four research questions (RQs):

RQ1 (Effectiveness): How effectively can CSPM reduce the identification accuracy of cipher-classification models?

RQ2 (Efficiency): What is the computational overhead of CSPM in terms of perturbation generation time and perturbation magnitude?

RQ3 (Mechanistic Insight): How does the perturbation strength relate to attack effectiveness, and can the adversarial behavior of CSPM be explained in terms of its underlying mechanisms?

RQ4 (Ablation Study): How do the individual components of CSPM contribute to its overall performance?

5.1. Experiment Setup

All experiments are conducted on a computing platform equipped with an Intel Core i5-13600 CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU. Unless otherwise specified, the hyperparameters are set to (weight coefficient) throughout all experiments.

Dataset: The plaintext corpus used in our experiments is sourced from the Open American National Corpus (OANC). The original text is first segmented into 500,000 fixed-length fragments, from which 10,000 fragments are randomly selected to form the plaintext samples for our evaluation. Each plaintext sample is then encrypted under seven representative international cryptographic algorithms using randomly generated keys, producing a total of 70,000 binary ciphertext sequences (7 classes × 10,000 samples per class).

Identification Model: The cryptographic algorithms identification model is implemented as a three-layer fully connected multi-layer perceptron (MLP). Specifically, the network consists of an input layer matching the ciphertext feature dimension, followed by two hidden layers of 512 and 256 neurons, respectively, each activated by the ReLU function. A final softmax output layer produces the probability distribution over the seven cipher classes. The model is trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 128 for 50 epochs. Cross-entropy loss is employed as the objective function to optimize classification accuracy.

Cryptographic Algorithms for Experiments: To ensure that our study exhibits broad applicability and practical relevance, we incorporate seven widely used international standard ciphers representing three major categories of modern cryptography: block ciphers, stream ciphers, and public-key ciphers. These algorithms collectively cover diverse design paradigms and operational structures, providing a representative benchmark for evaluating the universality and robustness of the proposed method.

DES [

3]: is a symmetric-key block cipher standardized by NIST in 1977. It operates on 64-bit plaintext blocks with a 56-bit effective key length and adopts a 16-round Feistel network structure. DES is historically significant as one of the earliest widely deployed encryption standards in commercial applications.

AES-128 [

4]: is a symmetric-key substitution–permutation network (SPN) block cipher standardized by NIST in 2001. It encrypts 128-bit plaintext blocks using a 128-bit key across 10 transformation rounds. AES is currently the de facto international standard for government, banking, and embedded security systems.

KASUMI [

25]: is a symmetric 64-bit block cipher standardized by 3GPP for use in 2G and 3G mobile communication security. It adopts a Feistel-like structure derived from the MISTY1 cipher, with design optimizations for efficient hardware implementation in mobile network baseband environments.

Grain-128 [

26]: is a lightweight stream cipher designed for constrained devices. It employs a combination of a Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR) and a Nonlinear Feedback Shift Register (NLFSR) to generate keystream bits. It is widely adopted in low-power wireless security and sensor networks.

RSA [

5]: is a public-key cryptosystem based on the hardness of integer factorization. Unlike symmetric ciphers, RSA uses a pair of asymmetric keys (public/private) and operates on large integers instead of fixed-size blocks. It is commonly used for key exchange, authentication, and digital signatures.

PRESENT [

27]: is an ultra-lightweight block cipher and commonly used in RFID tags and IoT devices. It encrypts 64-bit blocks with either an 80-bit or 128-bit key using an SPN structure optimized for low-area hardware deployment.

Camellia [

28]: is a symmetric-key block cipher developed by NTT and Mitsubishi Electric and later standardized by ISO/IEC. It uses a 128-bit block size and supports key lengths of 128, 192, and 256 bits. Its structure resembles AES but includes additional Feistel-type layers, providing both performance efficiency and strong security guarantees across hardware and software platforms.

Owing to the structural differences among cryptographic algorithms, the ciphertext samples do not share a uniform length, even though the plaintext samples are partitioned into fixed-size segments. The length of ciphertext corresponding to each class is summarized in

Table 1. The unit of length in the table is bits. In addition, we identified the corresponding mimic class for each target class through experiments. For relevant details, please refer to

Table 2, where original algorithm indicates the target class and the mimic algorithm corresponds to the mimic class.

5.2. RQ1: Effectiveness

Goal and Setup. To comprehensively assess the effectiveness of the proposed CSPM method, we first perform a global greedy search across all cipher classes to measure the maximum achievable degradation in classification accuracy. The experiments cover all seven cryptographic algorithms under fifteen NIST feature configurations. For fairness and interpretability, cryptographic algorithms whose baseline classification accuracy falls below 50% under certain feature settings are excluded from subsequent evaluations. A classifier with such low baseline accuracy lacks sufficient discriminative capability, making it difficult to meaningfully assess the degradation effect introduced by CSPM. As a result, algorithms such as AES and PRESENT, which consistently exhibit weak baseline performance across all feature configurations, are omitted from the reported perturbation results.

Result and Analysis.

Table 3 summarizes the effectiveness of CSPM on five cryptographic algorithms under 15 NIST feature configurations. Here, Fe denotes the corresponding feature extraction methods (see details in

Section 2), whose definitions are provided in

Section 2 O refers to the original classification accuracy (%) before perturbation, F denotes the final accuracy (%) after applying the adversarial mask, and D indicates the accuracy decline (i.e., O − F), which quantifies the effectiveness of CSPM in misleading the classifier. For the remaining algorithms, cases where the baseline accuracy falls below 50% are considered non-informative and are marked as ‘x’.

As shown in

Table 3, CSPM consistently achieves substantial degradation—exceeding 25% in all valid attack scenarios—demonstrating strong capability to mislead the classifier. The most significant drop is observed for KASUMI under Feature 12, where the accuracy decreases from 71.82% to 2.32%, yielding a decline of 69.50%. Furthermore, for a certain cryptographic algorithm, the perturbation effectiveness varies with the feature representation. For example, KASUMI experiences a 58.09% decline under Feature 3 (Linear Complexity test) but only 44.06% under Feature 7 (Approximate Entropy test). This discrepancy arises from the distinct sensitivity of different statistical features to adversarial perturbations: Linear Complexity (i.e., Feature 3) captures structural regularities that are more susceptible to perturbations, while Approximate Entropy (i.e., Feature 7) measures higher-order randomness, which is inherently more robust.

5.3. RQ2: Efficiency

Goal and Setup. To further assess the practicality of CSPM, we evaluate the perturbation cost, measured as the number of flipped bits. This number is a critical indicator because it reflects both the visibility and the feasibility of CSPM in real-world scenarios: fewer bit-flipping times correspond to lower modification overhead and stronger stealthiness. In addition, to quantify the computational burden of the proposed method, we measured the execution time required for each perturbation mask generation round. This analysis allows us to examine whether CSPM can construct perturbation masks under a reasonable time budget.

Result and Analysis.

Table 4 indicates the performance of CSPM on five cryptographic algorithms across 15 feature settings, along with the corresponding perturbation ratios. Here, D denotes the accuracy decline, while P represents the perturbation percentage (i.e., the number of flipped bits relative to the total ciphertext length). Since ciphertext lengths differ among cryptographic algorithms, the absolute number of flipped bits is not directly comparable; therefore, perturbation percentages provide a normalized and fair metric. As shown in the table, the average perturbation percentage is 13.06% and the lowest perturbation percentage is only 7.94%, indicating that CSPM can cause substantial classifier degradation with only a small number of bit flips, demonstrating both high stealthiness and efficiency.

Moreover, the general trend suggests a positive correlation between the performance drop and perturbation percentage, i.e., larger perturbation percentages tend to induce stronger degradation. However, some cases deviate from this tendency. For example, for RSA, the attack under Feature 5 (Random Excursions Test) causes a 26.35% drop with a 9.38% perturbation percentage, whereas Feature 10 (Serial Test) results in a slightly larger drop of 27.14% while using only an 8.46% perturbation percentage. This discrepancy highlights that perturbation effectiveness also depends on feature sensitivity: certain features are more responsive to local bit flips and can be effectively disrupted with fewer modifications, while others require more substantial perturbation to trigger misclassification. Thus, CSPM does not merely rely on perturbation magnitude; it exploits structurally “critical” bit positions to maximize attack impact, demonstrating its precision and robustness against cryptanalysis.

We measured the per-iteration time of CSPM’s greedy lookup procedure, where each trial flip requires applying the candidate mask to the test samples (via bitwise XOR), extracting features through , and performing inference with the pre-trained DNN. Because each of these steps—especially feature extraction—has variable computational cost, the per-lookup latency is strongly dependent on the chosen NIST feature. In our experiments across 15 NIST feature extractors, the per-iteration evaluation time was observed to range approximately from 25 s to 85 s on the experimental platform. It is important to emphasize that this timing reflects an offline mask-generation cost, not an online or real-time requirement. CSPM produces class-level masks that are computed once (or periodically) and then applied to many ciphertexts, so the one-time generation cost can be amortized over large volumes of traffic. Consequently, an individual mask’s apparent per-iteration expense becomes negligible when distributed over lots of ciphertexts.

5.4. RQ3: Mechanistic Insight

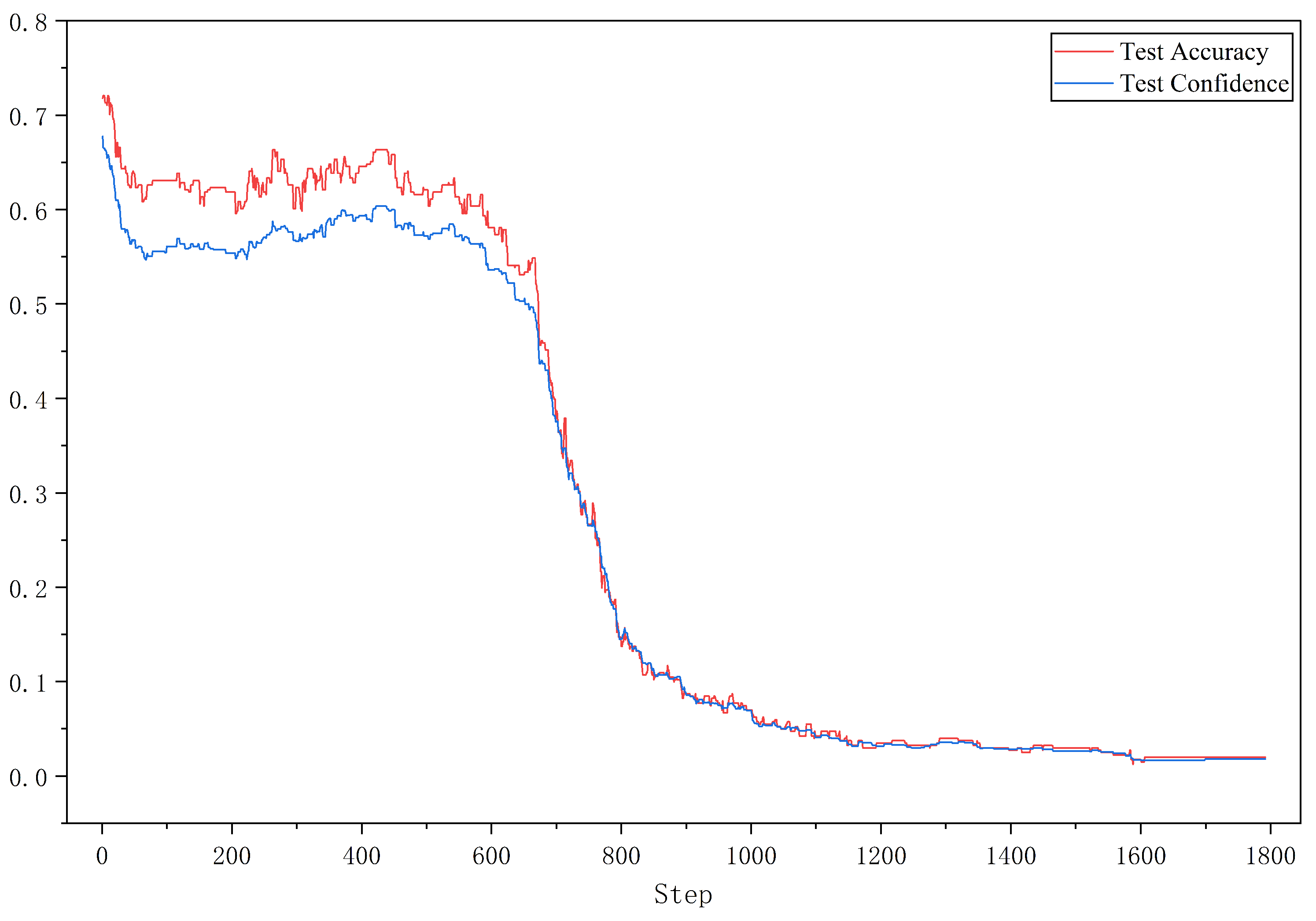

Goal and Setup. To further investigate how the perturbation strength impacts attack performance, we analyze the dynamic variation of model confidence and classification accuracy during the bit-flipping process. Two representative cases are selected under the Feature 12 configuration: KASUMI (which achieves the most significant degradation, with accuracy dropping to 2.32%) and RSA (which exhibits strong initial identification performance under the same setting).

Analysis and Result.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate the change in average confidence and accuracy on the test set with respect to the number of bit-flips. For both algorithms, the trends of confidence decay and accuracy decline are largely consistent. Since CSPM selects perturbation positions based on confidence reduction estimated from the training set, minor fluctuations appear on the test curves; yet the overall trend is a monotonic improvement in attack effectiveness as the flipping process proceeds.

Specifically, for KASUMI, the degradation is relatively mild at the beginning and end of the flipping sequence, while the middle stage exhibits a noticeably steeper decline, indicating that certain structural regions of the cipher are more sensitive to perturbations. In contrast, RSA shows a more uniform and nearly linear degradation trend, suggesting a more stable relationship between perturbation scale and identification failure. These results confirm that the evolution of attack effectiveness is inherently linked to the structural characteristics of different cipher designs.

5.5. RQ4: Ablation Study

Goal and Setup. To further investigate the effectiveness of each component in our ranking-based greedy search, we conduct an ablation study on Feature 4 for four representative ciphers: Camellia, DES, KASUMI, and RSA. Feature 4 is selected because it provides the largest number of valid algorithms under consistent experimental conditions, allowing us to perform comparative analysis across multiple ciphers within the same feature configuration. Specifically, we examine how each scoring mechanism contributes to the construction of the mask by individually isolating the mimicry score and the specificity score, and comparing them with a random flipping strategy and our complete CSPM method.

For each feature, we design four experimental settings: (1) Sorting and flipping based solely on the mimicry score (without using the specificity score); (2) Sorting and flipping based solely on the specificity score (without using the mimicry score); (3) Random flipping as an uninformed baseline; (4) Full CSPM, where both scores are jointly used for ranking.

To ensure a fair comparison, all four experiments use the same number of flipped bits, which is equal to the final number of flipped positions determined by the full CSPM in that scenario. The random flipping strategy is also constrained to this same perturbation budget.

Result and Analysis. As shown in

Table 5, CSPM consistently achieves the best performance across all evaluated feature settings. Compared with the random flipping baseline, the accuracy drop is improved by more than 15% in all cases, with the maximum improvement reaching

38.92% (59.30–20.38%). This demonstrates that the effectiveness of misleading the classifier primarily depends on which bits are flipped rather than how many bits are perturbed, emphasizing the importance of perturbation position selection.

Moreover, CSPM also outperforms the two single-score variants, i.e., mimicry-score-only and specificity-score-only flipping. This indicates a complementary relationship between the two ranking mechanisms: the mimicry score tends to identify bits that directly steer the ciphertext samples toward the decision boundary of the classifier, while the specificity score captures the bits that globally distort the extracted feature distribution.

Additionally, the relative improvement observed across different ciphers suggests that the internal redundancy and diffusion properties of cryptographic algorithms also influence their susceptibility to adversarial perturbations. For example, block ciphers with higher diffusion depth (e.g., Camellia, DES) exhibit moderate degradation margins, indicating partial resilience to localized bit manipulations, whereas algorithms with lower diffusion complexity (e.g., KASUMI) are more easily disrupted due to their stronger dependence on low-order statistical structures.

Overall, the ablation study validates that both the dual-score ranking mechanism and the cipher-dependent feature sensitivity are critical to the success of CSPM, confirming its robustness and adaptability across heterogeneous cryptographic algorithms.

6. Discussion and Future Work

6.1. Discussion

Dependence on statistics features. CSPM is primarily designed to interfere with feature-based cipher identification models that rely on handcrafted statistical descriptors such as NIST-15 features, which reflect observable bit-level regularities in ciphertexts. If the adversary instead employs deep representation learning or end-to-end neural fingerprinting models, the mapping between perturbations and extracted features may become highly nonlinear, thereby diminishing the transferability and effectiveness of the generated perturbations.

Limited transferability. The perturbation is generated at the class level but assumes distributional consistency between the samples in perturbation subset and the samples in the test set. In real-world heterogeneous deployments (e.g., different implementations, or channel noise), prototype drift may occur, leading to reduced transferability of the generated masks.

Generalizability to End-to-End Deep Learning Models. While the current implementation of CSPM primarily targets feature-based identifiers relying on handcrafted descriptors (e.g., NIST-15), its core optimization mechanism—black-box greedy search—is inherently model-agnostic. This framework can be readily extended to end-to-end deep learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) or Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), which learn representations directly from raw ciphertext bits.

Practical Deployment in Encryption Workflows. CSPM is designed for seamless integration into practical secure communication systems such as TLS or VPN workflows. The key advantage lies in the offline capability of mask generation. In a real-world deployment, the adversarial mask does not need to be computed per packet. Instead, it can be pre-generated and negotiated during the initial handshake phase, similar to a session key or initialization vector (IV). During runtime transmission, the sender applies the mask via a lightweight bitwise XOR operation immediately after encryption. This decoupling of generation and application ensures that CSPM introduces negligible computational overhead and zero latency penalties, acting as a transparent privacy layer compatible with existing protocols.

6.2. Future Work

In this work, we validated the efficacy of CSPM primarily against feature-based classifiers implemented via Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP). Recognizing the rapid advancement of deep learning in cryptanalysis, our future work will focus on evaluating the robustness of CSPM against end-to-end deep learning architectures, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Residual Networks (ResNets). Specifically, we aim to investigate whether the perturbations generated based on statistical features can maintain their adversarial effectiveness when transferred to models that learn representations directly from raw ciphertext bits. Additionally, we plan to explore the integration of CSPM into a real-time feedback loop to adaptively counter evolving deep-learning-based traffic analysis models.