Validation and Cultural Adaptation of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) Questionnaire in Arabic Language Widely Spoken in a Region with a High Prevalence of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Validation of the PACV Questionnaire in Arabic Language

2.2.1. Forward and Backward Translation

2.2.2. Content Validity and Expert Evaluation

2.2.3. Pilot Testing and Cognitive Interviewing

2.2.4. Score Interpretation, Data Management, and Psychometric Analysis

2.3. Statistical and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Participants

3.2. Predictors of Parental COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy

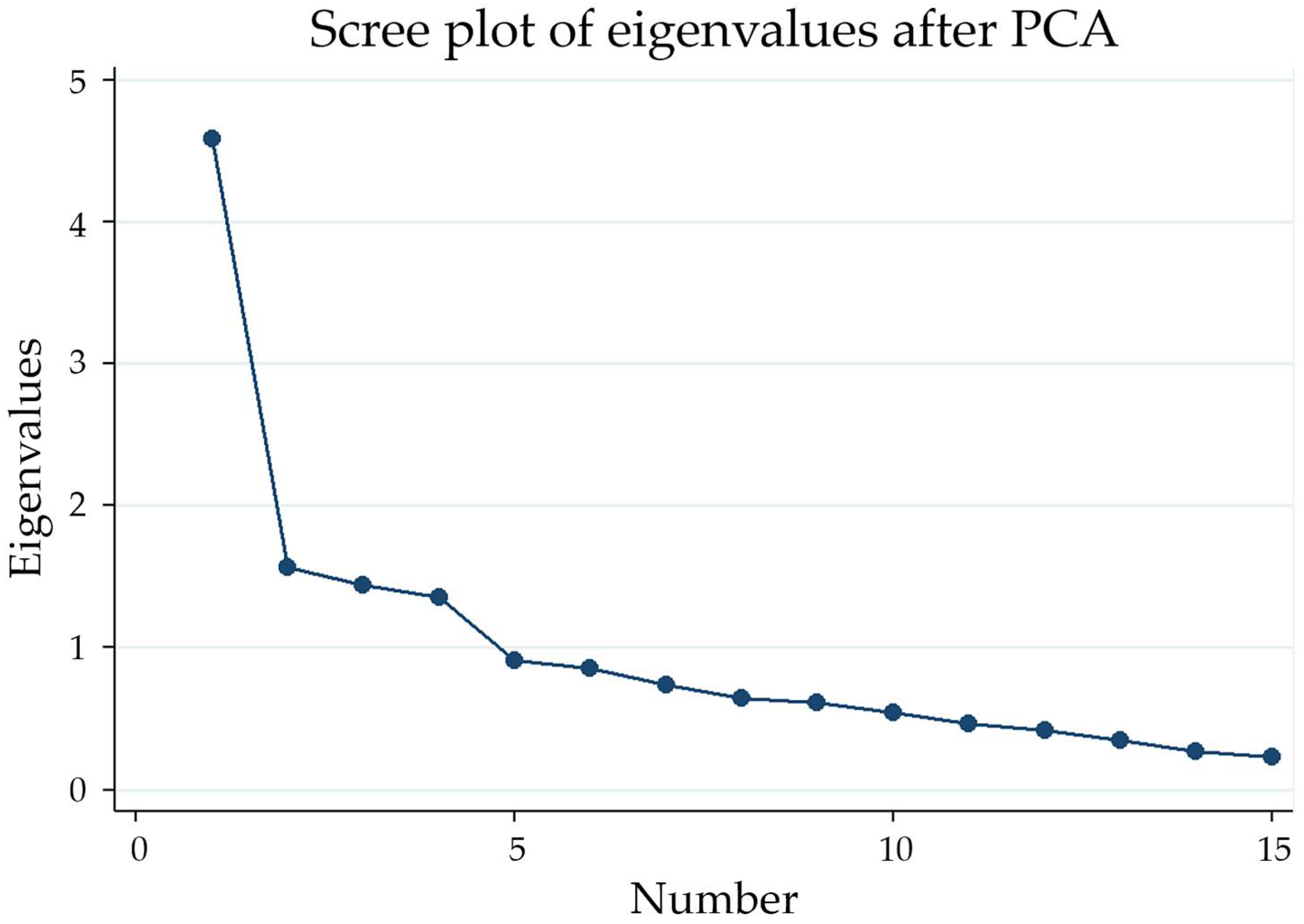

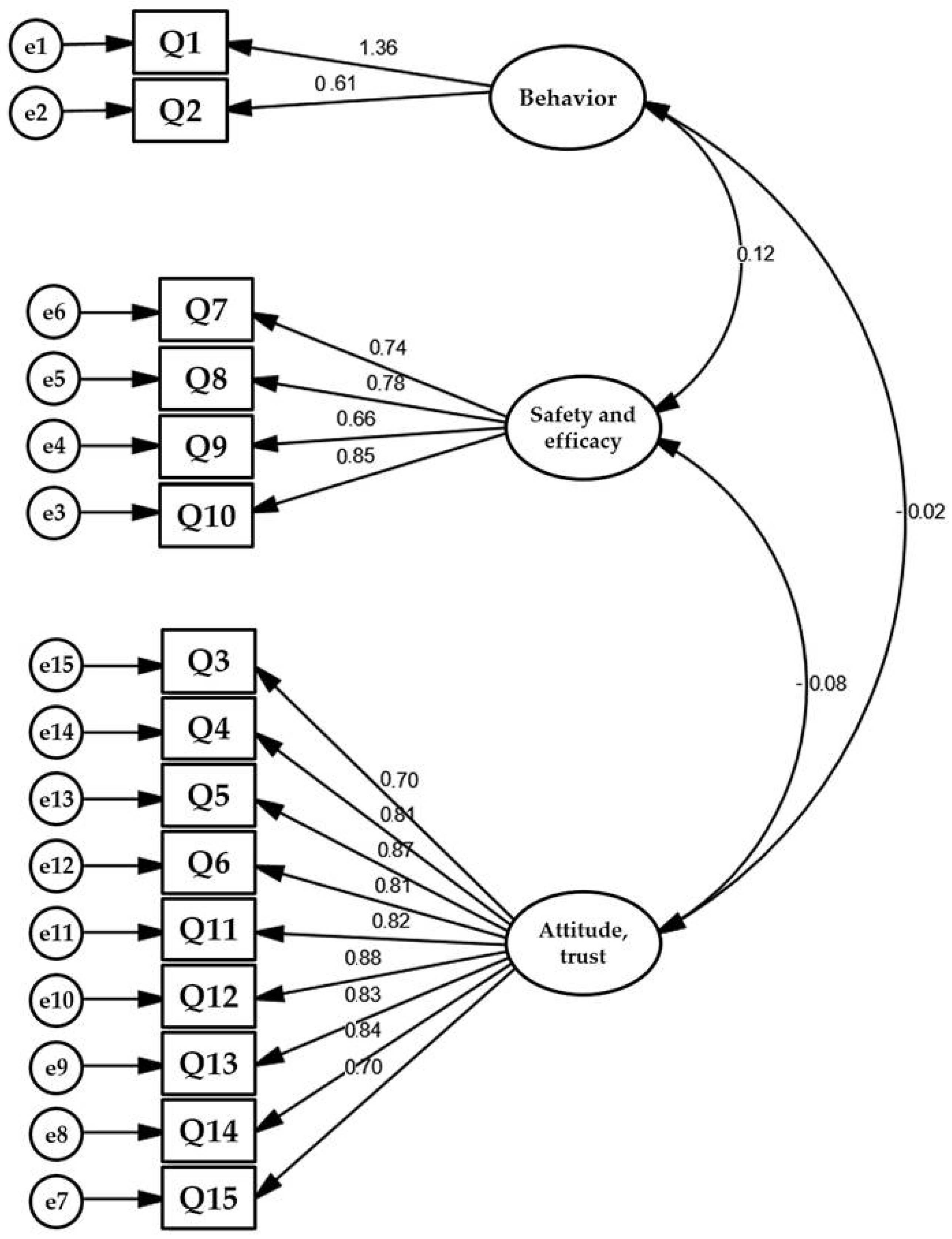

3.3. Factorial Analysis

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Wu, C.P.; Adhi, F.; Culver, D. Vaccination for COVID-19: Is it important and what should you know about it? Cleve Clin. J. Med. 2021, 1–7, (Online ahead of print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazy, R.M.; Ashmawy, R.; Hamdy, N.A.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Reyad, O.A.; Elmalawany, D.; Almaghraby, A.; Shaaban, R.; Taha, S.H.N. Efficacy and Effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgin, E. Omicron is supercharging the COVID vaccine booster debate. Nature 2021. (Online ahead of print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). COVID-19 Confirmed Cases and Deaths: Age- and Sex-Disaggregated Data. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/covid-19-confirmed-cases-and-deaths-dashboard/ (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Zimmermann, P.; Pittet, L.F.; Finn, A.; Pollard, A.J.; Curtis, N. Should children be vaccinated against COVID-19? Arch. Dis. Child. 2022, 107, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götzinger, F.; Santiago-García, B.; Noguera-Julián, A.; Lanaspa, M.; Lancella, L.; Calò Carducci, F.I.; Gabrovska, N.; Velizarova, S.; Prunk, P.; Osterman, V.; et al. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: A multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. Coronavirus Infections in Children Including COVID-19: An Overview of the Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention Options in Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnoli, R.; Votto, M.; Licari, A.; Brambilla, I.; Bruno, R.; Perlini, S.; Rovida, F.; Baldanti, F.; Marseglia, G.L. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Interim Statement on COVID-19 Vaccination for Children and Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/24-11-2021-interim-statement-on-covid-19-vaccination-for-children-and-adolescents (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Say, D.; Crawford, N.; McNab, S.; Wurzel, D.; Steer, A.; Tosif, S. Post-acute COVID-19 outcomes in children with mild and asymptomatic disease. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, e22–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, A.L.; Kuppermann, N.; Florin, T.A.; Tancredi, D.J.; Xie, J.; Kim, K.; Finkelstein, Y.; Neuman, M.I.; Salvadori, M.I.; Yock-Corrales, A.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Conditions Among Children 90 Days After SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2223253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.; Nguyen, V.; Navaratnam, A.M.D.; Shrotri, M.; Kovar, J.; Hayward, A.C.; Fragaszy, E.; Aldridge, R.W.; Hardelid, P. Prevalence of persistent symptoms in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a household cohort study in England and Wales. medRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Tang, K.; Levin, M.; Irfan, O.; Morris, S.K.; Wilson, K.; Klein, J.D.; Bhutta, Z.A. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents. Lancet Infect Dis 2020, 20, e276–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.K.; Pilania, R.K.; Bhatt, G.C.; Atlani, M.; Kumar, A.; Malik, S. Acute kidney injury following multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2022, 1–14, (Online ahead of print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, R.; Russell, S.; Saulle, R.; Croker, H.; Stansfield, C.; Packer, J.; Nicholls, D.; Goddings, A.L.; Bonell, C.; Hudson, L.; et al. School Closures During Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-being Among Children and Adolescents During the First COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnani, G.; Bardanzellu, F.; Pintus, M.C.; Fanos, V.; Marcialis, M.A. COVID-19 Vaccination in Children: An Open Question. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2022, 18, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sam-Agudu, N.A.; Quakyi, N.K.; Masekela, R.; Zumla, A.; Nachega, J.B. Children and adolescents in African countries should also be vaccinated for COVID-19. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA NEWS RELEASE: FDA Authorizes Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine for Emergency Use in Children 5 through 11 Years of Age. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-emergency-use-children-5-through-11-years-age (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- The European Medicines Agency (EMA). EMA Recommends Approval of Spikevax for Children Aged 6 to 11. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-recommends-approval-spikevax-children-aged-6-11 (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Interim Statement on COVID-19 Vaccination for Children. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/11-08-2022-interim-statement-on-covid-19-vaccination-for-children (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Chen, F.; He, Y.; Shi, Y. Parents’ and Guardians’ Willingness to Vaccinate Their Children against COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Jin, H.; Lin, L. Vaccination against COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of acceptability and its predictors. Prev. Med. 2021, 150, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajar, J.K.; Sallam, M.; Soegiarto, G.; Sugiri, Y.J.; Anshory, M.; Wulandari, L.; Kosasih, S.A.P.; Ilmawan, M.; Kusnaeni, K.; Fikri, M.; et al. Global Prevalence and Potential Influencing Factors of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy: A Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allington, D.; McAndrew, S.; Moxham-Hall, V.; Duffy, B. Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2021, 1–12, (Online ahead of print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sanafi, M.; Sallam, M. Psychological Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Healthcare Workers in Kuwait: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the 5C and Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs Scales. Vaccines 2021, 9, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Eid, H.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Yaseen, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M.; Al-Sanafi, M.; Sallam, M. A Global Map of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Rates per Country: An Updated Concise Narrative Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdou, M.S.; Kheirallah, K.A.; Aly, M.O.; Ramadan, A.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Elbarazi, I.; Deghidy, E.A.; El Saeh, H.M.; Salem, K.M.; Ghazy, R.M. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination psychological antecedent assessment using the Arabic 5c validated tool: An online survey in 13 Arab countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qerem, W.; Jarab, A.; Hammad, A.; Alasmari, F.; Ling, J.; Alsajri, A.H.; Al-Hishma, S.W.; Abu Heshmeh, S.R. Iraqi Parents’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices towards Vaccinating Their Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holder, J. The New York Times. Tracking Coronavirus Vaccinations Around the World. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/world/covid-vaccinations-tracker.html (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Ritchie, H.; Mathieu, E.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Beltekian, D.; Roser, M. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Published Online at OurWorldInData.org. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Opel, D.J.; Mangione-Smith, R.; Taylor, J.A.; Korfiatis, C.; Wiese, C.; Catz, S.; Martin, D.P. Development of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents: The parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey. Hum. Vaccin. 2011, 7, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opel, D.J.; Taylor, J.A.; Mangione-Smith, R.; Solomon, C.; Zhao, C.; Catz, S.; Martin, D. Validity and reliability of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6598–6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Azizi, F.S.; Kew, Y.; Moy, F.M. Vaccine hesitancy among parents in a multi-ethnic country, Malaysia. Vaccine 2017, 35, 2955–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.M.; Kerr, G.B.; Orobio, J.; Munoz, F.M.; Correa, A.; Villafranco, N.; Monterrey, A.C.; Opel, D.J.; Boom, J.A. Development of a Spanish version of the parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2019, 15, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opel, D.J.; Furniss, A.; Zhou, C.; Rice, J.D.; Spielvogle, H.; Spina, C.; Perreira, C.; Giang, J.; Dundas, N.; Dempsey, A.; et al. Parent Attitudes Towards Childhood Vaccines After the Onset of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States. Acad. Pediatr. 2022, 0, S1876–S2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. Egypt Authorizes Pfizer’s COVID-19 Vaccine for 12 to 15 Year-Olds. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/egypt-authorizes-pfizers-covid-19-vaccine-12-15-year-olds-2021-11-28/ (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- The Official Saudi Press Agency. SFDA Approves Using Pfizer Vaccine to Age Category 5–11. Available online: https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2301189 (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, A.; Skrutkowski, M. Translating instruments into other languages: Development and testing processes. Cancer Nurs 2002, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjersing, L.; Caplehorn, J.R.M.; Clausen, T. Cross-cultural adaptation of research instruments: Language, setting, time and statistical considerations. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abushariah, M.A.-A.M.; Ainon, R.N.; Zainuddin, R.; Alqudah, A.A.M.; Elshafei Ahmed, M.; Khalifa, O.O. Modern standard Arabic speech corpus for implementing and evaluating automatic continuous speech recognition systems. J. Frankl. Inst. 2012, 349, 2215–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.S.B. ABC of Content Validation and Content Validity Index Calculation. Educ. Med. J. 2019, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M.W. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. J. Black Psychol. 2018, 44, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarewaju, V.O.; Jafflin, K.; Deml, M.J.; Zimmermann, C.; Sonderegger, J.; Preda, T.; Staub, H.; Kwiatkowski, M.; Kloetzer, A.; Huber, B.M.; et al. Application of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) survey in three national languages in Switzerland: Exploratory factor analysis and Mokken scale analysis. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 2652–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuwaidi, A.R.; Elbarazi, I.; Al-Hamad, S.; Aldhaheri, R.; Sheek-Hussein, M.; Narchi, H. Vaccine hesitancy and its determinants among Arab parents: A cross-sectional survey in the United Arab Emirates. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 3163–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Halim, H.; Abdul-Razak, S.; Md Yasin, M.; Isa, M.R. Validation study of the Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines (PACV) questionnaire: The Malay version. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatatbeh, M.; Albalas, S.; Khatatbeh, H.; Momani, W.; Melhem, O.; Al Omari, O.; Tarhini, Z.; A’Aqoulah, A.; Al-Jubouri, M.; Nashwan, A.J.; et al. Children’s rates of COVID-19 vaccination as reported by parents, vaccine hesitancy, and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children: A multi-country study from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, O.S.; Alfayez, O.M.; Al Yami, M.S.; Asiri, Y.A.; Almohammed, O.A. Parents’ Hesitancy to Vaccinate Their 5-11-Year-Old Children Against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: Predictors From the Health Belief Model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 842862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machingaidze, S.; Wiysonge, C.S. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak, M.P.; Domaradzki, J.; Walkowiak, D. Better Late Than Never: Predictors of Delayed COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake in Poland. Vaccines 2022, 10, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, S.B.; Wilson-Genderson, M.; Garcia, D.T.; Akinkugbe, A.A.; Mosavel, M. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Hesitancy in a Sample of US Adults: Role of Perceived Satisfaction With Health, Access to Healthcare, and Attention to COVID-19 News. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 665724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, A.; Montelpare, W.J. Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy: Implications for COVID-19 Public Health Messaging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, S.A.; Siau, C.S.; Chen, W.S.; Low, W.Y.; Faria de Moura Villela, E.; Pengpid, S.; Hasan, M.T.; Sessou, P.; Ditekemena, J.D.; Amodan, B.O.; et al. Adults’ Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine for Children in Selected Lower- and Middle-Income Countries. Vaccines 2021, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voo, J.Y.H.; Lean, Q.Y.; Ming, L.C.; Md Hanafiah, N.H.; Al-Worafi, Y.M.; Ibrahim, B. Vaccine Knowledge, Awareness and Hesitancy: A Cross Sectional Survey among Parents Residing at Sandakan District, Sabah. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Zhao, H.; Nicholas, S.; Maitland, E.; Liu, R.; Hou, Q. Parents’ Decisions to Vaccinate Children against COVID-19: A Scoping Review. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, R.K. Helping patients with ethical concerns about COVID-19 vaccines in light of fetal cell lines used in some COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4242–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.L.; Yap, J.F.C. The role of religiosity in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. J. Public Health 2021, 43, e529–e530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 18–29 | 15 (6.70) |

| 30–39 | 134 (59.82) | |

| 40–49 | 62 (37.68) | |

| ≥50 | 13 (5.80) | |

| Sex | Male | 69 (30.80) |

| Female | 155 (69.20) | |

| Education | Below university education | 25 (11.21) |

| University education | 103 (46.19) | |

| Postgraduate | 95 (42.60) | |

| Number of children | One child | 91 (40.63) |

| Two children | 83 (37.05) | |

| Three children | 39 (17.41) | |

| Four children | 11 (4.91) | |

| Relation to the child | Mother | 155 (69.20) |

| Father | 69 (30.80) | |

| Place of work | Government | 150 (66.96) |

| Private | 42 (18.75) | |

| Not employed | 32 (14.29) | |

| Health-insured | Yes | 177 (79.02) |

| No | 47 (20.98) | |

| Income | Not enough; on a loan and cannot pay back | 15 (6.70) |

| Not enough; on a loan but can pay back | 48 (21.43) | |

| Enough | 135 (60.27) | |

| Enough and saving | 26 (11.61) | |

| Older adults living in the same home | Yes | 64 (28.70) |

| No | 159 (71.30) | |

| Family size | 2 | 12 (5.36) |

| 3–4 | 102 (45.54) | |

| ≥5 | 110 (49.11) | |

| Previous COVID-19 infection | Yes | 96 (42.86) |

| No | 68 (30.36) | |

| Not sure | 60 (26.79) | |

| COVID-19 vaccine status | Does not want to take the vaccine | 30 (13.64) |

| Took the first dose and is awaiting the second | 15 (6.82) | |

| Took the first dose but does not want to take the second dose | 3 (1.36) | |

| Took the first and second doses and is awaiting the booster dose | 96 (43.64) | |

| Took the first and second doses but did not want to take the booster dose | 31 (14.09) | |

| Took the three doses | 31 (14.09) | |

| Wants to take the vaccine, but it is not scheduled yet | 14 (6.36) | |

| Parent with chronic diseases | Yes | 54 (24.11) |

| No | 170 (75.89) | |

| Children with chronic disease | Yes | 13 (5.80) |

| No | 211 (94.20) | |

| Children received scheduled vaccines | Yes | 163 (72.77) |

| No | 61 (27.23) | |

| Children received influenza vaccine | Yes | 51 (22.77) |

| No | 168 (75.0) | |

| I do not know | 5 (2.23) | |

| Children with previous COVID-19 Infection | Yes | 31 (13.84) |

| No | 151 (67.41) | |

| I do not know | 42 (18.75) | |

| Parents intentions to allow COVID-19 vaccination for children | Yes | 98 (43.75) |

| No | 126 (56.25) | |

| Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines (PACV) dichotomized | Non-hesitant (PACV Score < 21) | 11 (7.56) |

| Hesitant (PACV Score ≥ 21) | 208 (92.44) |

| Variables | Category | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 1 | Ref. |

| Female | 1.94 (1.09–3.44) | 0.020 | |

| Age | 18–29 | 1 | Ref. |

| 30–39 | 1.47 (0.50–4.30) | 0.480 | |

| 40–49 | 0.63 (0.20–1.96) | 0.430 | |

| ≥50 | 1.40 (0.31–6.33) | 0.660 | |

| Relation to the child | Mother | 1 | Ref. |

| Father | 0.52 (0.29–0.92) | 0.020 | |

| Education | High school and below | 1 | Ref. |

| Undergraduate degree | 5.45 (2.07–14.33) | 0.001 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 2.62 (1.00–6.86) | 0.040 | |

| Place of work | Government | 1 | Ref. |

| Private | 1.40 (0.69–2.80) | 0.350 | |

| Not employed | 2.84 (1.20–6.73) | 0.017 | |

| Work Sector | Health | 1 | Ref. |

| Non-health | 1.21 (0.71–2.06) | 0.480 | |

| Insurance | Yes | 1 | Ref. |

| No | 1.32 (0.68–2.56) | 0.397 | |

| Income | Not enough; took a loan and cannot pay back | 1 | Ref. |

| Not enough; took a loan but can pay back | 1.33 (0.42–4.30) | 0.630 | |

| Enough | 0.97 (0.33–2.83) | 0.980 | |

| Enough and save | 1.96 (0.53–7.31) | 0.310 | |

| Older adults living within the same home | Yes | 1 | Ref. |

| No | 1.08 (0.62–2.00) | 0.730 | |

| Family size | 2 | 1 | Ref. |

| 3–4 | 1.02 (0.30–3.43) | 0.974 | |

| ≥5 | 0.83 (0.25–2.76) | 0.757 | |

| Previous COVID-19 infection | Yes | 1 | Ref. |

| No | 0.36 (0.19–0.68) | 0.002 | |

| Not sure | 0.46 (0.23–0.88) | 0.020 | |

| Vaccine status | Does not want to take the vaccine | 1 | Ref. |

| Took the first dose and is awaiting the second | 0.13 (0.03–0.58) | 0.007 | |

| Took the first dose but does not want to take the second dose | 0.31 (0.02–4.23) | 0.380 | |

| Took the first and second doses and is awaiting the booster dose | 0.12 (0.08–0.37) | <0.001 | |

| Took the first and second doses but did not want to take the booster dose | 1.03 (0.23–4.59) | 0.960 | |

| Took the three doses | 0.08 (0.02–0.30) | <0.001 | |

| Wants to take the vaccine, but it is not scheduled yet | 0.38 (0.08–1.84) | 0.232 | |

| Children with chronic disease | No | 1 | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.8 (0.53–6.05) | 0.337 | |

| Children intake of scheduled vaccines | Yes | 1 | Ref. |

| No | 1.55 (0.84–2.84) | 0.158 | |

| Children intake for the influenza vaccine | Yes | 1 | Ref. |

| No | 1.65 (0.88–3.10) | 0.117 | |

| I do not know | 0.75 (0.11–4.87) | 0.763 | |

| A child with previous COVID-19 Infection | Yes | 1 | Ref. |

| No | 0.88 (0.40–1.94) | 0.760 | |

| I do not know | 0.52 (0.20–1.34) | 0.180 | |

| Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines (PACV) | Non-hesitant (PACV Score < 21) | 1 | Ref. |

| Hesitant (PACV Score ≥ 21) | 11.20 (2.50–50.28) | 0.002 |

| Variables | Adjusted OR (95%) CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Education | ||

| High school and below | 1 | Ref. |

| Undergraduate degree | 3.58 (1.02–11.7) | 0.045 |

| Postgraduate degree | 1.57 (0.40–6.05) | 0.051 |

| Previous COVID-19 infection | ||

| Yes | 1 | Ref. |

| No | 0.25 (0.10–0.58) | 0.001 |

| Not sure | 0.20 (0.11–0.62) | 0.002 |

| Vaccine status | ||

| Does not want to take the vaccine | 1 | Ref. |

| Took the first dose and is awaiting the second | 0.07 (0.01–0.46) | 0.005 |

| Took the first dose but does not want to take the second dose | 0.18 (0.01–3.53) | 0.262 |

| Took the first and second doses and is awaiting the booster dose | 0.08 (0.02–0.35) | 0.001 |

| Took the first and second doses but did not want to take the booster dose | 0.61 (0.10–3.75) | 0.600 |

| Took the three doses | 0.04 (0.01–0.23) | <0.001 |

| Wants to take the vaccine, but it is not scheduled yet | 0.20 (0.03–1.42) | 0.109 |

| Parent Attitudes About Childhood Vaccines (PACV) | ||

| Non-hesitant (PACV Score < 21) | 1 | Ref. |

| Hesitant (PACV Score ≥ 21) | 10.80 (1.92–60.9) | 0.007 |

| Domain | Mean ± SD | Item-to-Score Correlation | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 224 | |||

| Total score | 26.68 ± 4.46 | ||

| Behavior | 3.89 ± 0.57 | ||

| Q1 | 1.95 ± 0.38 | 0.88 | <0.001 |

| Q2 | 1.94 ± 0.29 | 0.79 | <0.001 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.57 | ||

| Attitude | 15.73 ± 3.28 | ||

| Q3 | 1.51 ± 0.76 | 0.60 | <0.001 |

| Q4 | 2.15 ± 0.83 | 0.41 | <0.001 |

| Q5 | 1.18 ± 0.46 | 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Q6 | 2.39 ± 0.75 | 0.02 | 0.811 |

| Q7 | 1.76 ± 0.80 | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Q11 | 1.21 ± 0.55 | 0.48 | <0.001 |

| Q12 | 1.53 ± 0.81 | 0.64 | <0.001 |

| Q13 | 1.38 ± 0.62 | 0.73 | <0.001 |

| Q14 | 1.25 ± 0.58 | 0.50 | <0.001 |

| Q15 | 1.36 ± 0.58 | 0.58 | <0.001 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.74 | ||

| Safety and efficacy | 7.05 ± 2.14 | ||

| Q8 | 2.53 ± 0.77 | 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Q9 | 2.42 ± 0.91 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Q10 | 2.10 ± 0.70 | 0.79 | <0.001 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.82 | ||

| Overall Scale Cronbach’s alpha | 0.80 |

| Factors | Attitude | Safety and Efficacy | Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 1 | - | - |

| Safety and efficacy | 0.51 | 1 | - |

| Behavior | −0.093 | 0.032 | 1 |

| Item | Attitude | Safety and Efficacy | Behavior | Uniqueness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.66 |

| Q2 | −0.14 | −0.10 | 0.60 | 0.59 |

| Q3 | 0.55 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.64 |

| Q4 | 0.16 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.98 |

| Q5 | 0.78 | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.39 |

| Q6 | −0.21 | −0.18 | −0.02 | 0.89 |

| Q7 | 0.21 | −0.09 | −0.09 | 0.96 |

| Q8 | −0.02 | 0.80 | −0.04 | 0.38 |

| Q9 | 0.00 | 0.85 | −0.03 | 0.27 |

| Q10 | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.07 | 0.55 |

| Q11 | 0.42 | 0.04 | −0.10 | 0.79 |

| Q12 | 0.64 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.50 |

| Q13 | 0.76 | 0.11 | −0.03 | 0.32 |

| Q14 | 0.67 | −0.19 | −0.02 | 0.64 |

| Q15 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.66 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

ElSayed, D.A.; Bou Raad, E.; Bekhit, S.A.; Sallam, M.; Ibrahim, N.M.; Soliman, S.; Abdullah, R.; Farag, S.; Ghazy, R.M. Validation and Cultural Adaptation of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) Questionnaire in Arabic Language Widely Spoken in a Region with a High Prevalence of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7090234

ElSayed DA, Bou Raad E, Bekhit SA, Sallam M, Ibrahim NM, Soliman S, Abdullah R, Farag S, Ghazy RM. Validation and Cultural Adaptation of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) Questionnaire in Arabic Language Widely Spoken in a Region with a High Prevalence of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2022; 7(9):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7090234

Chicago/Turabian StyleElSayed, Doaa Ali, Etwal Bou Raad, Salma A. Bekhit, Malik Sallam, Nada M. Ibrahim, Sarah Soliman, Reham Abdullah, Shehata Farag, and Ramy Mohamed Ghazy. 2022. "Validation and Cultural Adaptation of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) Questionnaire in Arabic Language Widely Spoken in a Region with a High Prevalence of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 7, no. 9: 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7090234

APA StyleElSayed, D. A., Bou Raad, E., Bekhit, S. A., Sallam, M., Ibrahim, N. M., Soliman, S., Abdullah, R., Farag, S., & Ghazy, R. M. (2022). Validation and Cultural Adaptation of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) Questionnaire in Arabic Language Widely Spoken in a Region with a High Prevalence of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 7(9), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7090234