A Systematic Scoping Review on Migrant Health Coverage in Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Data Extraction

3. Results

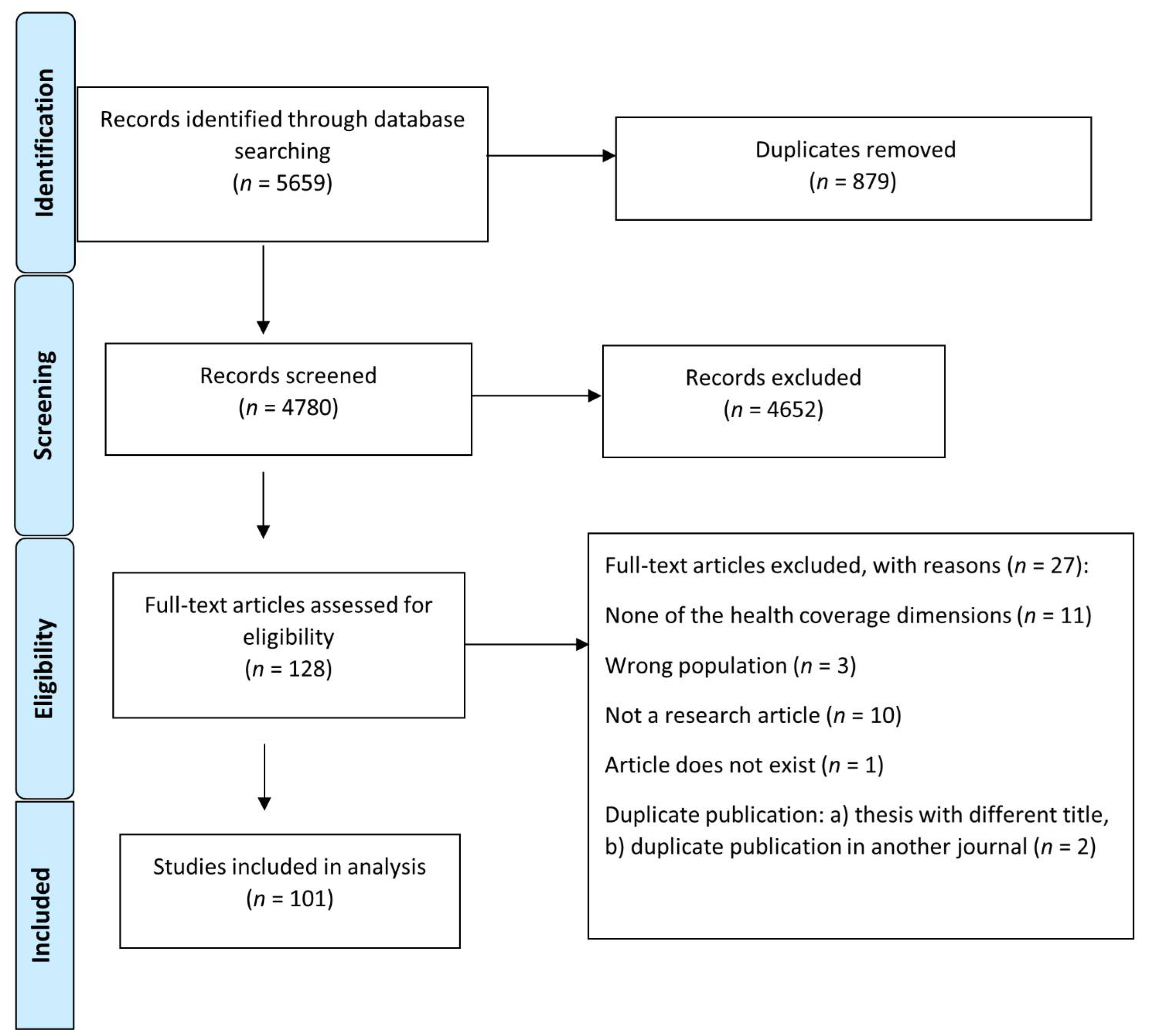

3.1. Study Selection

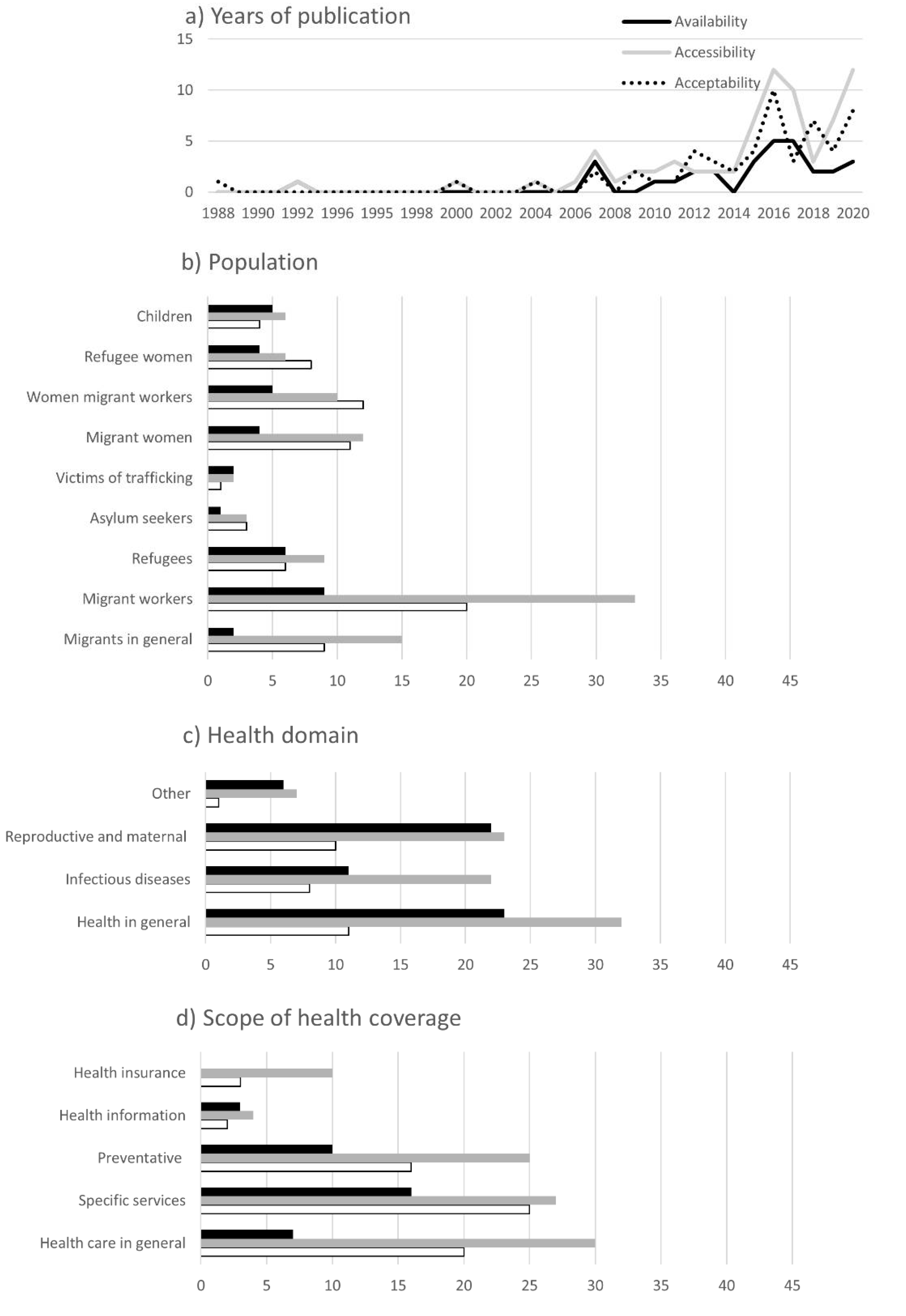

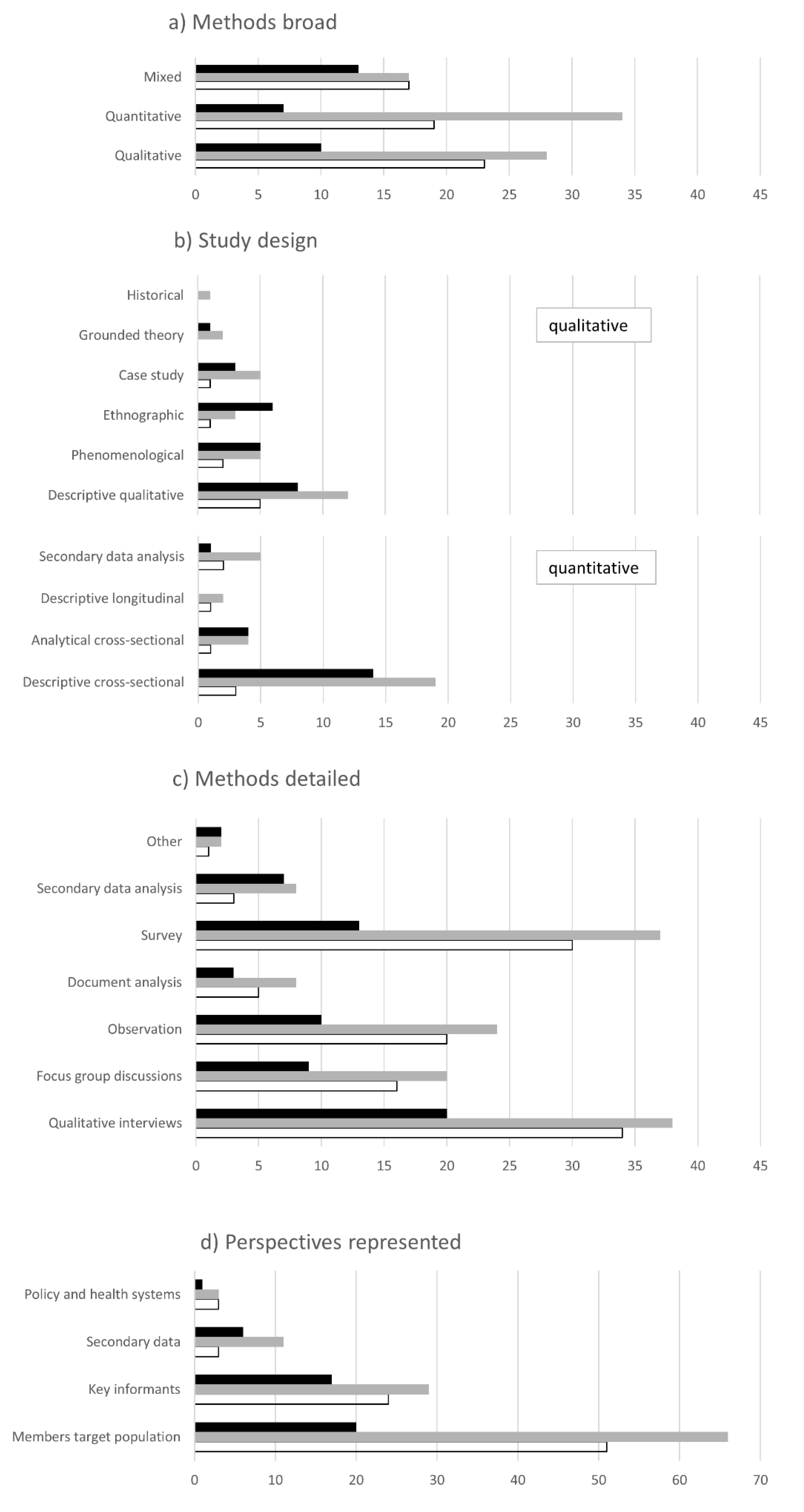

3.2. Characteristics of Studies

3.3. Objectives and Results of Included Publications

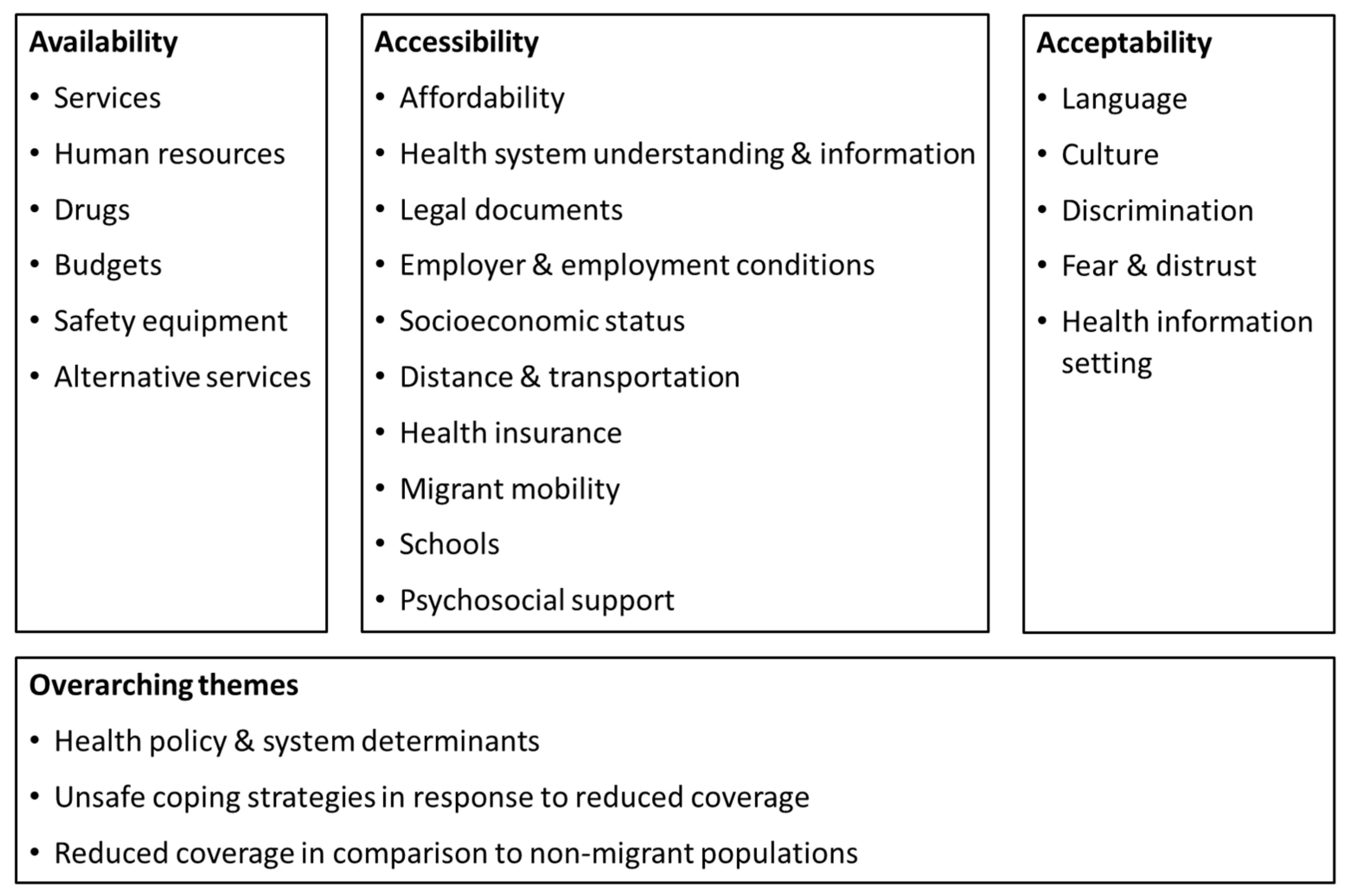

3.3.1. Availability

3.3.2. Accessibility

3.3.3. Acceptability

3.3.4. Overarching Themes

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guinto, R.L.L.R.; Curran, U.Z.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Pocock, N.S. Universal health coverage in “One ASEAN”: Are migrants included? Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 25749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Putthasri, W.; Prakongsai, P.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Evolution and complexity of government policies to protect the health of undocumented/illegal migrants in Thailand—The unsolved challenges. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2017, 10, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). Asia-Pacific Migration Report 2020; ESCAP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harkins, B.; Lindgren, D. Labour Migration in the ASEAN Region: Assessing the Social and Economic Outcomes for Migrant Workers. Available online: www.migratingoutofpoverty.org/files/file.php?name=harkins-labour-migration-in-asean-update.pdf&site=354 (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- World Health Organization South-East Asia Region. Health of Refugees and Migrants; WHO SEARO: New Delhi, India, 2018.

- UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS. The Gap Report; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wangroongsarb, P.; Satimai, W.; Khamsiriwatchara, A.; Thwing, J.; Eliades, J.M.; Kaewkungwal, J.; Delacollette, C. Respondent-driven sampling on the Thailand-Cambodia border. II. Knowledge, perception, practice and treatment-seeking behaviour of migrants in malaria endemic zones. Malar. J. 2011, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschirhart, N.; Nosten, F.; Foster, A.M. Migrant tuberculosis patient needs and health system response along the Thailand-Myanmar border. Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration Key Migration Terms. Available online: https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms#Irregular-migration (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Leiter, K.; Suwanvanichkij, V.; Tamm, I.; Iacopino, V.; Beyrer, C. Human Rights Abuses and Vulnerability to HIV/AIDS: The Experiences of Burmese Women in Thailand. Health and Human Rights. 2006, 9, 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkins, B. Thailand Migration Report 2019; United Nations Thematic Working Group on Migration in Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UN WOMEN. Information Series on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity; UN WOMEN: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tschirhart, N.; Jiraporncharoen, W.; Angkurawaranon, C.; Hashmi, A.; Nosten, S.; McGready, R.; Ottersen, T. Choosing where to give birth: Factors influencing migrant women’s decision making in two regions of Thailand. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Pudpong, N.; Prakongsai, P.; Putthasri, W.; Hanefeld, J.; Mills, A. The Devil Is in the Detail-Understanding Divergence between Intention and Implementation of Health Policy for Undocumented Migrants in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; Prof, N.P.; Tan, S.T.; Pajin, L.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Wickramage, K.; McKee, M.; Prof, K.P. Healthcare is not universal if undocumented migrants are excluded. BMJ 2019, 366, l4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, N.S.; Chan, Z.; Loganathan, T.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Allotey, P.; Chan, W.K.; Tan, D. Moving towards culturally competent health systems for migrants? Applying systems thinking in a qualitative study in Malaysia and Thailand. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakunwisit, D.; Areesantichai, C. Factors Associated with Immunization Status among Myanmar Migrant Children Aged 1–2 Years in Tak Province, Thailand. J. Health Res. 2015, 29, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 Version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 10 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. ILO Global Estimates on Migrant Workers; International Labour Office Geneva: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime|OHCHR 2000. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/protocol-prevent-suppress-and-punish-trafficking-persons (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- UNHCR. What Is a Refugee? Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/what-is-a-refugee.html (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- UNHCR. Asylum-Seekers. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/asylum-seekers.html (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Tanahashi, T. Health service coverage and its evaluation. Bull. World Health Organ. 1978, 56, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Hanan, K.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; Malley, L.O. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toothong, T.; Tipayamongkholgul, M.; Suwannapong, N.; Suvannadabba, S. Evaluation of mass drug administration in the program to control imported lymphatic filariasis in Thailand. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunpeuk, W.; Julchoo, S.; Phaiyarom, M.; Sinam, P.; Pudpong, N.; Suphanchaimat, R. A cross-sectional study on disparities in unmet need among refugees and asylum seekers in thailand in 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunpeuk, W.; Teekasap, P.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Julchoo, S.; Phaiyarom, M.; Sinam, P.; Pudpong, N.; Suphanchaimat, R. Understanding the problem of access to public health insurance schemes among cross-border migrants in Thailand through systems thinking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, B.K. The Work of Inscription: Antenatal Care, Birth Documents, and Shan Migrant Women in Chiang Mai. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2017, 31, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobstetter, M.; Sietstra, C.; Walsh, M.; Leigh, J.; Foster, A.M. “In rape cases we can use this pill”: A multimethods assessment of emergency contraception knowledge, access, and needs on the Thailand-Burma border. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2015, 130, E37–E41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewkuekoonkit, A.; Chantanavich, S. Rohingya in Thailand: Existing Social Protection and Dynamic Circumstances. Asian Rev. 2018, 31, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Saether, S.T.; Chawphrae, U.; Zaw, M.M.; Keizer, C.; Wolffers, I. Migrants’ access to antiretroviral therapy in Thailand. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2007, 12, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Putthasri, W.; Sommanustweechai, A.; Khitdee, C.; Thaichinda, C.; Kantamaturapoj, K.; Leelahavarong, P.; Jumriangrit, P.; Topothai, T.; Wisaijohn, T. HIV/AIDS health care challenges for cross-country migrants in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. HIV/AIDS Res. Palliat. Care 2014, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschirhart, N.; Thi, S.S.; Swe, L.L.; Nosten, F.; Foster, A.M. Treating the invisible: Gaps and opportunities for enhanced TB control along the Thailand-Myanmar border. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschirhart, N.; Sein, T.; Nosten, F.; Foster, A.M. Migrant and Refugee Patient Perspectives on Travel and Tuberculosis along the Thailand-Myanmar Border: A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; Chuah, F.L.H.; Howard, N. Southeast Asian health system challenges and responses to the ‘Andaman Sea refugee crisis’: A qualitative study of health-sector perspectives from Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiyaporn, H.; Julchoo, S.; Phaiyarom, M.; Sinam, P.; Kunpeuk, W.; Pudpong, N.; Allotey, P.; Chan, Z.X.; Loganathan, T.; Pocock, N.; et al. Strengthening the migrant-friendliness of Thai health services through interpretation and cultural mediation: A system analysis. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2020, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thein, S.S.; Thepthien, B. on Unmet need for family planning among Myanmar migrant women in Bangkok, Thailand. Br. J. Midwifery 2020, 28, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Sinam, P.; Phaiyarom, M.; Pudpong, N.; Julchoo, S.; Kunpeuk, W.; Thammawijaya, P. A cross sectional study of unmet need for health services amongst urban refugees and asylum seekers in Thailand in comparison with Thai population, 2019. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, P.P.; Geater, A.F. Healthcare seeking preferences of Myanmar migrant seafarers in the deep south of Thailand. Int. Marit. Health 2021, 72, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.; Pongpanich, S.; Robson, M.G. Health Seeking Behaviours among Myanmar Migrant Workers in Ranong Province, Thailand. J. Health Res. 2009, 23, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Isarabhakdi, P. Meeting at the Crossroads: Myanmar Migrants and Their Use of Thai Health Care Services. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2016, 13, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, Y.W.; Panza, A. Knowledge, Attitude, Barriers and Preventive Behaviors of Tuberculosis among Myanmar Migrants at Hua Fai Village, Mae Sot District, Tak Province, Thailand. J. Health Res. 2014, 28, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kaji, A.; Thi, S.S.; Smith, T.; Charunwatthana, P.; Nosten, F.H. Challenges in tackling tuberculosis on the Thai-Myanmar border: Findings from a qualitative study with health professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanok, S.; Parker, D.M.; Parker, A.L.; Lee, T.; Min, A.M.; Ontuwong, P.; Oo Tan, S.; Sirinonthachai, S.; McGready, R. Empirical lessons regarding contraception in a protracted refugee setting: A descriptive study from Maela camp on the Thai-Myanmar border 1996–2015. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srithongtham, O.; Songpracha, S.; Sanguanwongwan, W.; Charoenmukayananta, S. The Impact of Health Service of the Community Hospital Located in Thailand’s Border: Migrant from Burma, LAOS, and Cambodia. J. Arts Humanit. 2013, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanwichatkul, T.; Schmied, V.; Liamputtong, P.; Burns, E. The perceptions and practices of Thai health professionals providing maternity care for migrant Burmese women: An ethnographic study. Women Birth 2021, 35, e356–e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedeon, J.; Hsue, S.N.; Foster, A.M. “ I came by the bicycle so we can avoid the police ”: Factors shaping reproductive health decision-making on the Thailand-Burma border. Int. J. Popul. Stud. 2016, 2, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellmeth, G.; Plugge, E.H.; Nosten, S.; Oo, M.M.; Fazel, M.; Charunwatthana, P.; Nosten, F.; Fitzpatrick, R.; McGready, R. Living with severe perinatal depression: A qualitative study of the experiences of labour migrant and refugee women on the Thai-Myanmar border. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijken, M.J.; Gilder, M.E.; Thwin, M.M.; Kajeechewa, H.M.L.; Wiladphaingern, J.; Lwin, K.M.; Jones, C.; Nosten, F.; McGready, R. Refugee and migrant women’s views of antenatal ultrasound on the thai burmese border: A mixed methods study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Asgary, R. Community Coping Strategies in Response to Hardship and Human Rights Abuses Among Burmese Refugees and Migrants at the Thai-Burmese Border: A Qualitative Approach. Fam. Community Health 2016, 39, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedeon, J.; Hsue, S.N.; Walsh, M.; Sietstra, C.; MarSan, H.; Foster, A.M. Assessing the experiences of intra-uterine device users in a long-term conflict setting: A qualitative study on the Thailand-Burma border. Confl. Health 2015, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tousaw, E.; Moo, S.N.H.G.; Arnott, G.; Foster, A.M. “It is just like having a period with back pain”: Exploring women’s experiences with community-based distribution of misoprostol for early abortion on the Thailand-Burma border. Contraception 2018, 97, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srisai, P.; Phaiyarom, M.; Suphanchaimat, R. Perspectives of Migrants and Employers on the National Insurance Policy (Health Insurance Card Scheme) for Migrants: A Case Study in Ranong, Thailand. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 2227–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chotiga, P. HIV Testing in Antenatal Care Clinic: The Experience of Burmese Migrant Women in Northern Thailand; University of East Anglia: Norwich, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, S. Borders of fertility: Unplanned pregnancy and unsafe abortion in Burmese women migrating to Thailand. Health Care Women Int. 2007, 28, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phanwichatkul, T.; Burns, E.; Liamputtong, P.; Schmied, V. The experiences of Burmese healthcare interpreters (Iam) in maternity services in Thailand. Women Birth 2018, 31, e152–e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirilak, S.; Okanurak, K.; Wattanagoon, Y.; Chatchaiyalerk, S. Community participation of cross-border migrants for primary health care in Thailand. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 28, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousaw, E.; La, R.K.; Arnott, G.; Chinthakanan, O.; Foster, A.M. “Without this program, women can lose their lives”: Migrant women’s experiences with the Safe Abortion Referral Programme in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Reprod. Health Matters 2017, 25, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webber, G.C.; Spitzer, D.L.; Somrongthong, R.; Cong Dat, T.; Kounnavongsa, S. Migrant Beer Promoters’ Experiences Accessing Reproductive Health Care in Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam: Lessons for Planners and Providers. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2015, 27, NP1128–NP1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mon, H.O.; Xenos, P. Perception and Usage of Compulsory Migrant Health Insurance Scheme by Adult Myanmar Migrants in Bang Khun Thian District, Bangkok Metropolitan Area, Thailand. J. Health Res. 2015, 29, S207–S213. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J. Uneven inclusion: Consequences of universal healthcare in Thailand. Citizsh. Stud. 2013, 17, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskhao, P.; Ninphanomchai, S.; Thongyuan, S.; Sringernyuang, L.; Kittayapong, P. The living and working conditions including accessibility to healthcare of migrants working in rubber plantations in eastern Thailand. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2015, 20, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Phaiyarom, M.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Pudpong, N.; Sinam, P.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Julchoo, S.; Kunpeuk, W. Access to non-communicable disease (Ncd) services among urban refugees and asylum seekers, relative to the thai population, 2019: A case study in Bangkok, Thailand. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 3423–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naing, S.H.H.; Isaramalai, S.-A.; Sukmag, P. Policy Literacy, Barriers, and Gender Impact on Accessibility to Healthcare Services under Compulsory Migrant Health Insurance among Myanmar Migrant Workers in Thailand. Hindawi J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020, 8165492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivirojana, N.; Punpuing, S.; Robinson, C.; Sciortino, R.; Vapattanawong, P. Marginalization, morbidity and mortality: A case study of Myanmar migrants in Ranong Province, Thailand. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2014, 22, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatchawanchanchanakij, P. Factors Affecting Access to Health Service Management of Transnational Myanmar Labours in Ranong, Thailand. PSAKU Int. J. Interdiscip. Res. 2018, 6, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myo-Lin-Zaw; Tiraphat, S.; Hongkrailert, N. Factors affecting the utilization of quality antenatal care services among Myanmar migrants in Thai health care facilities: Tak and Samut Sakhon Province. J. Public Health Dev. 2016, 14, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrook, E.; Min, M.C.; Kajeechiwa, L.; Wiladphaingern, J.; Paw, M.K.; Paw, M.; Pimanpanarak, J.; Hiranloetthanyakit, W.; Min, A.M.; Tun, N.W.; et al. Distance matters: Barriers to antenatal care and safe childbirth in a migrant population on the Thailand-Myanmar border from 2007 to 2015, a pregnancy cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kågesten, A.E.; Zimmerman, L.; Robinson, C.; Lee, C.; Bawoke, T.; Osman, S.; Schlecht, J. Transitions into puberty and access to sexual and reproductive health information in two humanitarian settings: A cross-sectional survey of very young adolescents from Somalia and Myanmar. Confl. Health 2017, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khongthanachayopit, S.; Laohasiriwong, W. Accessibility to health services among migrant workers in the Northeast of Thailand. F1000Research 2017, 6, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musumari, P.M.; Chamchan, C. Correlates of HIV Testing Experience among Migrant Workers from Myanmar Residing in Thailand: A Secondary Data Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thetkathuek, A.; Jaidee, W.; Jaidee, P. Access to Health Care by Migrant Farm Workers on Fruit Plantations in Eastern Thailand Access to Health Care by Migrant Farm Workers on Fruit Plantations in. J. Agromedicine 2017, 22, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongvattananon, P.; Phochai, S.; Thongbai, W. Factors Predicting Healthcare Behaviors of Pregnant Migrant Laborers. Bangk. Med. J. 2020, 16, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonchutima, S.; Sukonthasab, S.; Sthapitanonda, P. Myanmar Migrants ’ Access to Information on HIV/AIDS in Thailand. J. Sports Sci. Health 2020, 1, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kamonroek, N.; Turnbull, N.; Suwanlee, S.R.; Peltzer, K. Health Care Accessibility of Migrants in Border Areas of Northeast, Thailand. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2020, 11, 792–796. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, S.; Whittaker, A. Kathy Pan, sticks and pummelling: Techniques used to induce abortion by Burmese women on the Thai border. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1512–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veerman, R.; Reid, T. Barriers to Health Care for Burmese Migrants in Phang Nga Province, Thailand. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2011, 13, 970–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Xu, J.Z.; Tanongsaksakul, W.; Suksangpleng, T.; Ekwattanakit, S.; Riolueang, S.; Telen, M.J.; Viprakasit, V. Feasibility of and barriers to thalassemia screening in migrant populations: A cross-sectional study of Myanmar and Cambodian migrants in Thailand. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.K.; Distefano, A.S.; Yang, J.S.; Wood, M.M. Displacement and HIV: Factors Influencing Antiretroviral Therapy Use by Ethnic Shan Migrants in Northern Thailand HHS Public Access. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2016, 27, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tschirhart, N.; Nosten, F.; Foster, A.M. Access to free or low-cost tuberculosis treatment for migrants and refugees along the Thailand-Myanmar border in Tak province, Thailand. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, G.; Spitzer, D.; Somrongthong, R.; Dat, T.C.; Kounnavongsa, S. Facilitators and barriers to accessing reproductive health care for migrant beer promoters in Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam: A mixed methods study. Global Health 2012, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonah, L.; Corwin, A.; January, J.; Shamu, S.; Van Der Putten, M. Barriers to Healthcare Access and Coping Mechanisms among Sub-Saharan African Migrants living in Bangkok, Thailand: A Qualitative Study. Med. J. Zambia 2016, 43, 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hegde, S.; Hoban, E.; Nevill, A. Unsafe abortion as a birth control method: Maternal mortality risks among unmarried cambodian migrant women on the Thai-Cambodia border. Asia Pacific J. Public Health 2012, 24, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunpuwan, M.; Punpuing, S.; Jaruruengpaisan, W.; Kinsman, J.; Wertheim, H. What is in the drug packet?: Access and use of non-prescribed poly-pharmaceutical packs (Yaa Chud) in the community in Thailand. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holumyong, C.; Ford, K.; Sajjanand, S.; Chamratrithirong, A. The Access to Antenatal and Postpartum Care Services of Migrant Workers in the Greater Mekong Subregion: The Role of Acculturative Stress and Social Support. J. Pregnancy 2018, 2018, 9241923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. The Role of Health Insurance in Improving Health Services Use by Thais and Ethnic Minority Migrants. Asia Pacific J. Public Health 2010, 22, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, T.; Geater, A.; Pungrassami, P. Migrant workers’ occupation and healthcare-seeking preferences for TB-suspicious symptoms and other health problems: A survey among immigrant workers in Songkhla province, southern Thailand. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2012, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pudpong, N.; Durier, N.; Julchoo, S.; Sainam, P.; Kuttiparambil, B.; Suphanchaimat, R. Assessment of a voluntary non-profit health insurance scheme for migrants along the thai-myanmar border: A case study of the migrant fund in thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunstadter, P. Ethnicity, socioeconomic characteristics and knowledge, beliefs and attitudes about HIV among Yunnanese Chinese, Hmong, Lahu and Northern Thai in a north-western Thailand border district. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 15 (Suppl. S3), S383–S400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosiyaporn, H.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Nipaporn, S.; Wanwong, Y.; Nopparattayaporn, P.; Poungkanta, W.; Puthasri, W. Budget Impact and Situation Analysis on the Basic Vaccination Service for Uninsured Migrant Children in Thailand. J. Health Syst. Res. 2018, 12, 404–419. [Google Scholar]

- Tuangratananon, T.; Julchoo, S.; Wanwong, Y.; Sinam, P.; Suphanchaimat, R. School health for migrant children: A myth or a must? Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2019, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinna, C.; Kaewkungwal, J.; Hattasingh, W.; Swaddiwudhipong, W.; Methakulchart, R.; Moungsookjareoun, A.; Lawpoolsri, S. Evaluation of immunization services for children of migrant workers along thailand–myanmar border: Compliance with global vaccine action plan (2011–2020). Vaccines 2020, 8, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzezinski, A.; Ann, L.B.; Morley, K.; Laohasiriwong, W. Developing mHealth System to Improve Health Services for the Burmese Migrant Population Living in the Mae Sot Region of Thailand; Harvard Medical School: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, A.M.; Arnott, G.; Hobstetter, M. Community-based distribution of misoprostol for early abortion: Evaluation of a program along the Thailand–Burma border. Contraception 2017, 96, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, S.; Mongkolpuet, L.P. Evaluative research in a refugee cAMP: The effectiveness of community health workers in khao I dang holding center, Thailand. Disasters 1988, 12, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suphanchaimat, R.; Kunpeuk, W.; Phaiyarom, M.; Nipaporn, S. The Effects of the Health Insurance Card Scheme on Out-of-Pocket Expenditure Among Migrants in Ranong Province, Thailand. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2019, 12, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnott, G.; Tho, E.; Guroong, N.; Foster, A.M. To be, or not to be, referred: A qualitative study of women from Burma’s access to legal abortion care in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittaporn, S.; Boonmongkon, P. Thailand’s health screening policy and practices: The case of Burmese migrants with tuberculosis. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 37, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pocock, N.S.; Kiss, L.; Oram, S.; Zimmerman, C. Labour Trafficking among Men and Boys in the Greater Mekong Subregion: Exploitation, Violence, Occupational Health Risks and Injuries. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusakabe, K.; Pearson, R. Working through exceptional space: The case of women migrant workers in Mae Sot, Thailand. Int. Sociol 2016, 31, 268–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodeker, G.; Neumann, C. Revitalization and Development of Karen Traditional Medicine for Sustainable Refugee Health Services at the Thai-Burma Border. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2012, 10, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkongdech, R.; Srisaenpang, S.; Tungsawat, S. Pulmonary TB among Myanmar Migrants in Samut Sakhon Province, Thailand: A Problem or not for the TB Control Program? Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2015, 46, 296–305. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.Z.; Foe, M.; Tanongsaksakul, W.; Suksangpleng, T.; Ekwattanakit, S.; Riolueang, S.; Telen, M.J.; Kaiser, B.N.; Viprakasit, V. Identification of Optimal Thalassemia Screening Strategies for Migrant Populations in Thailand: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Blood 2019, 134, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavati, S.; Plugge, E.; Suwanjatuporn, S.; Nosten, F. Barriers to immunization among children of migrant workers from Myanmar living in Tak province, Thailand. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maybin, S. A comparison of health provision and status in ban napho refugee cAMP and nakhon phanom province, northeastern Thailand. Disasters 1992, 16, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, N.S.; Tadee, R.; Tharawan, K.; Rongrongmuang, W.; Dickson, B.; Suos, S.; Kiss, L.; Zimmerman, C. “Because if we talk about health issues first, it is easier to talk about human trafficking”; findings from a mixed methods study on health needs and service provision among migrant and trafficked fishermen in the Mekong. Global Health 2018, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traisuwan, W. Oral health status and behaviors of pregnant migrant workers in Bangkok, Thailand: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yimyam, S. Accessibility to Health Care Services and Reproductive Health Care Behavior of Female Shan Migrant Workers. J. Public Health 2014, 42, 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kaji, A.; Parker, D.M.; Chu, C.S.; Thayatkawin, W.; Suelaor, J.; Charatrueangrongkun, R.; Salathibuppha, K.; Nosten, F.H.; McGready, R. Immunization Coverage in Migrant School Children Along the Thailand-Myanmar Border. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuangratananon, T.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Julchoo, S.; Sinam, P.; Putthasri, W. Education Policy for Migrant Children in Thailand and How It Really Happens; A Case Study of Ranong Province, Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, N.S.; Nguyen, L.H.; Lucero-Prisno III, D.E.; Zimmerman, C.; Oram, S. Occupational, physical, sexual and mental health and violence among migrant and trafficked commercial fishers and seafarers from the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS): Systematic review. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2018, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwi, S.H.; Katonyoo, C.; Chiangmai, N.N. Health Seeking Behaviors and Access To Health Services of Shan Migrant Workers in Hang Dong District, Chiang Mai Province. Kuakarun J. Nurs. 2016, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Boonchutima, S.; Sukonthasab, S.; Sthapitanonda, P. Educating Burmese migrants working in Thailand with HIV/AIDS public health knowledge—A perspective of public health officers. HIV AIDS Rev. 2017, 16, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration Thailand. Migration and HIV/AIDS in Thailand: Triangulation of Biological, Behavioural and Programmatic Response Data in Selected Provinces; International Organization for Migration Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sweileh, W.M.; Wickramage, K.; Pottie, K.; Hui, C.; Roberts, B.; Sawalha, A.F.; Zyoud, S.H. Bibliometric analysis of global migration health research in peer-reviewed literature (2000–2016). BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweileh, W.M. Global output of research on the health of international migrant workers from 2000 to 2017 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. Global Health 2018, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phanwichatkul, T.; Schmied, V.; Burns, E.; Liamputtong, P. Working Together to Provide Antenatal Care for Migrant Burmese Women: The Perspectives of Health Professionals and Bicultural Health Workers in Southern Thailand. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2016, 14, S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| Availability | Studies [31,32,33] aimed to identify available health services for certain migrant populations. |

| Migrant health needs | Study [34] stated to assess migrant health or service needs. |

| Health system responsiveness | Publications [28,35,36,37,38,39,40] went further to investigate health system functioning for migrants or responsiveness to health needs. Studies [17,41,42,43,44] aimed to explore health-seeking behaviours or preferences of migrants. |

| Health system stakeholder perspective | The focus of studies [2,16,45,46,47,48] was directed on the state, policy maker or provider perspective on challenges to migrant health coverage |

| Target population perspective | Studies [7,13,30,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] chose to examine target population perspectives. |

| Policy impact | Studies [2,14,33,63] looked at the effects of a new policy, policy reform, policy gaps or policy implementation on migrants. |

| Determinants, barriers and facilitators to health coverage | Studies [13,29,40,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] explored determinants of health coverage openly, whereas the authors of studies [27,31,44,49,51,78,79,80] directly aimed to identify barriers and/or facilitators and studies [66,81,82,83,84] coping strategies related to coverage. |

| Coping strategies related to limited health coverage | Referring to barriers, studies [57,85,86] focused on unsafe coping strategies or problematic use of services. |

| Role of specific factors for health coverage | Specific factors assumed to determine coverage, such as insurance, social support, bicultural translators, occupation, geographic factors or the human rights situation were focused on in articles [10,58,70,87,88,89,90]. |

| Health coverage in comparison to other populations | Studies [40,63,65,91,92] went further to detect in-between group differences, such as between migrants and Thai, ethnic minority or stateless populations. |

| Evaluate migrant health intervention | The goal of studies [2,54,93,94,95,96,97,98,99] was to evaluate a certain health intervention, such as migrant health insurance or health promotion or a community-based programme to determine the impact or feasibility of the intervention. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

König, A.; Nabieva, J.; Manssouri, A.; Antia, K.; Dambach, P.; Deckert, A.; Horstick, O.; Kohler, S.; Winkler, V. A Systematic Scoping Review on Migrant Health Coverage in Thailand. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7080166

König A, Nabieva J, Manssouri A, Antia K, Dambach P, Deckert A, Horstick O, Kohler S, Winkler V. A Systematic Scoping Review on Migrant Health Coverage in Thailand. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2022; 7(8):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7080166

Chicago/Turabian StyleKönig, Andrea, Jamila Nabieva, Amin Manssouri, Khatia Antia, Peter Dambach, Andreas Deckert, Olaf Horstick, Stefan Kohler, and Volker Winkler. 2022. "A Systematic Scoping Review on Migrant Health Coverage in Thailand" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 7, no. 8: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7080166

APA StyleKönig, A., Nabieva, J., Manssouri, A., Antia, K., Dambach, P., Deckert, A., Horstick, O., Kohler, S., & Winkler, V. (2022). A Systematic Scoping Review on Migrant Health Coverage in Thailand. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 7(8), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7080166