Challenges Perceived by Health Care Providers for Implementation of Contact Screening and Isoniazid Chemoprophylaxis in Karnataka, India

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

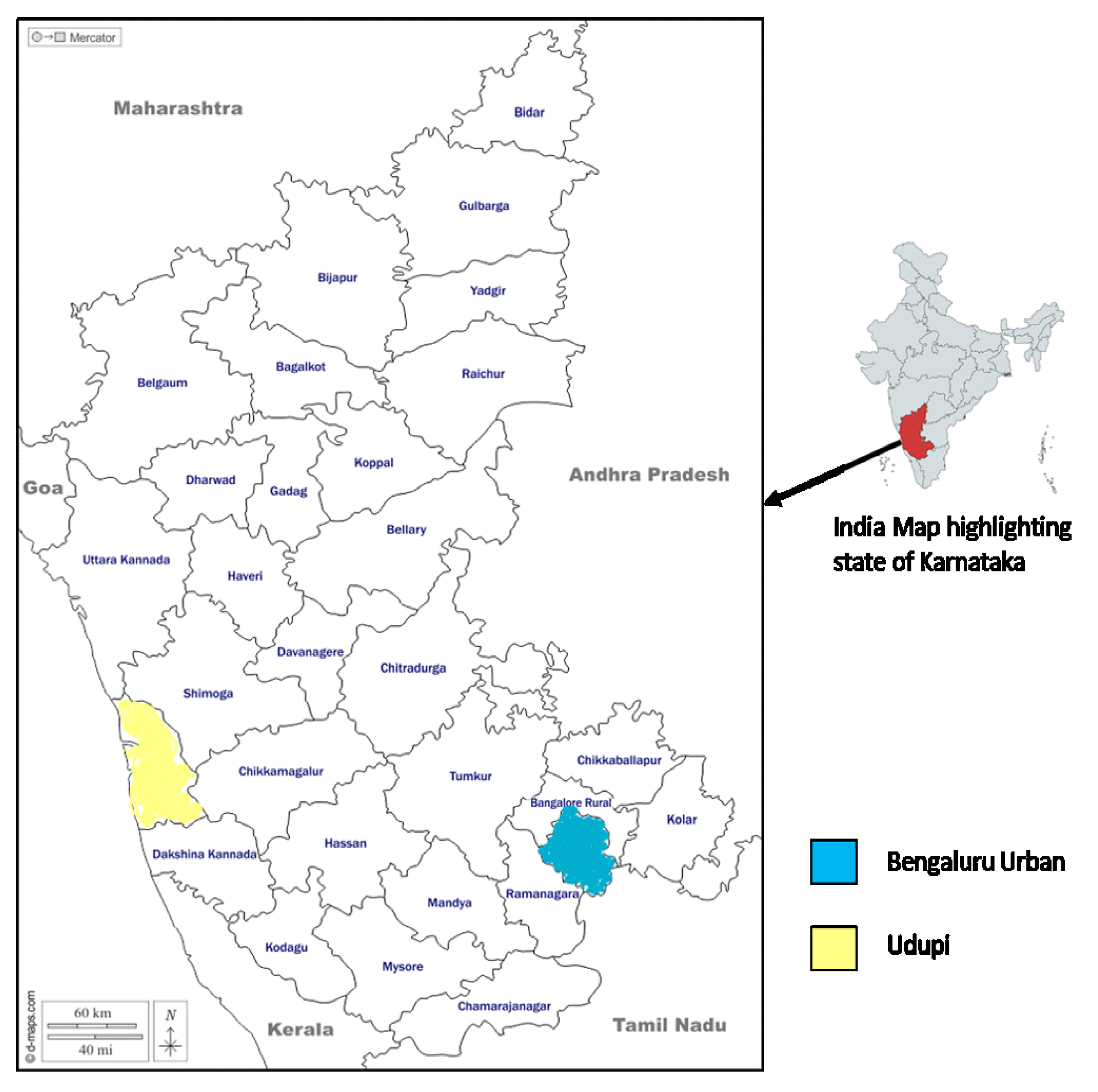

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethics Approval

3. Results

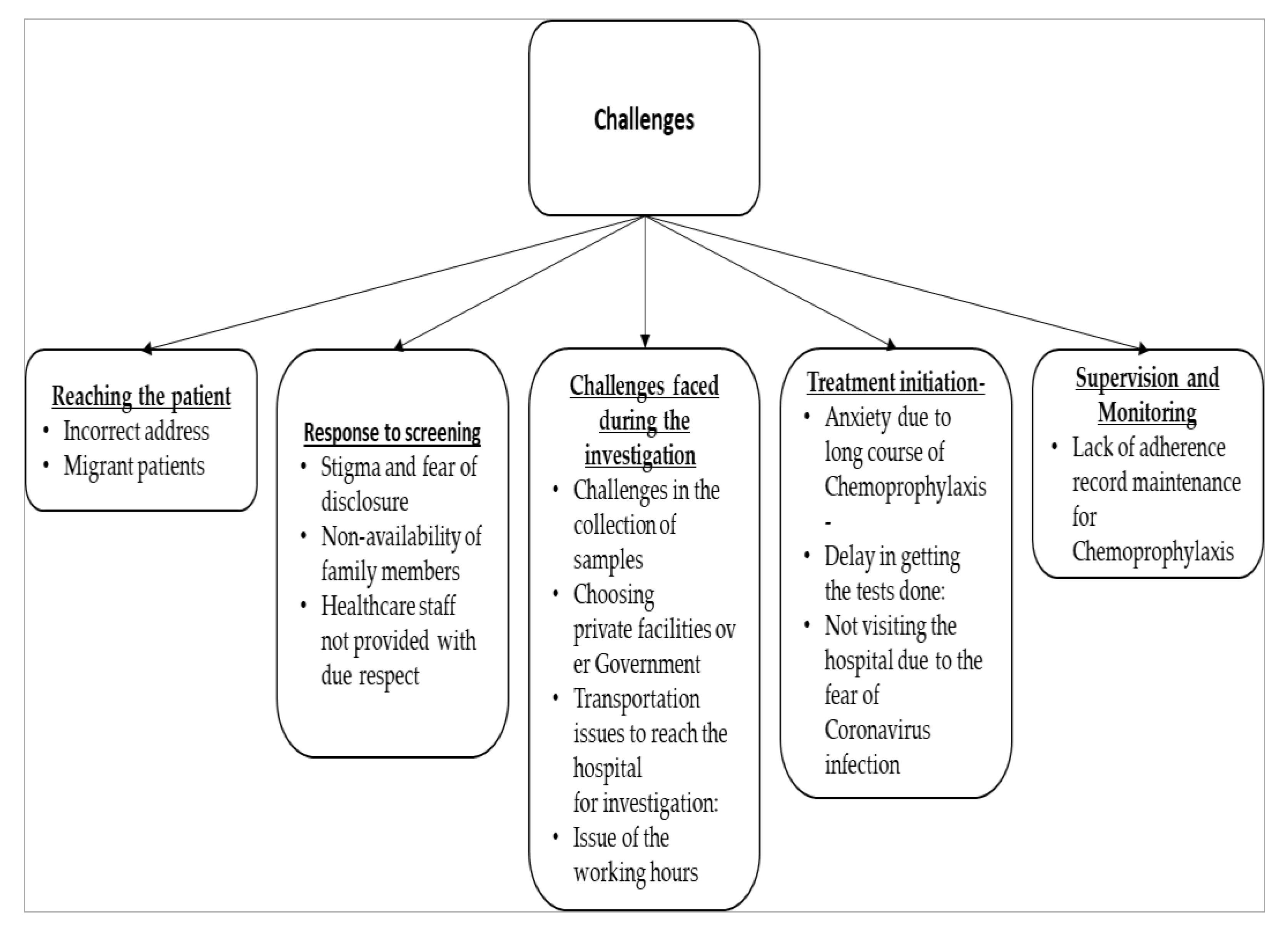

3.1. Challenges

3.1.1. Reaching the Patient

- 1.

- Incorrect address: The health care providers expressed those patients belonging to other districts provided the wrong address and contact number as they did not wish to be traced back and were hesitant to let their family members know about the disease. Although the percentage of people could be small, it still contributes to patients who are lost to follow-up. Some patients refrain from sharing it with their families as they believe that the family might not be supportive. The pediatric contacts from this kind of patient’s household will be missed for screening and evaluation.

“Wrong address and mobile numbers are given by daily wage workers particularly from districts like Koppala, Raichur, and Gadag…”(STS, Udupi district)

“It becomes difficult to reach the patient’s address. One of the patients had given us the wrong address. Later STS called them here to the hospital and that is when I got to know that the patient lives in my area”(ASHA, Bengaluru district)

- 2.

- Migrant patients: Many healthcare providers explained that most of the migrant population are from the northern part of the state who travel from place to place for their livelihood. Managing and ensuring treatment adherence becomes challenging when they frequently shift cities. The capital of Karnataka state, Bengaluru, is home to several lakhs of migrant workers who change their homes based on work. In addition, tracking such patients who move from place to place for a livelihood becomes extremely difficult. A good number of lost to follow-up cases belong to migrant workers in both districts. Children of such patients cannot be screened as they do not accompany their parents during migration.

“Migrant patients take the treatment for one month. They are mostly from Bijapur and Gulbarga. They will go back to their place, and we cannot trace them as their phone numbers and address will not be correct…”(STS, Udupi district)

“Bengaluru has a lot of migratory population if they leave this place then it becomes too challenging to monitor. When children go to their relative’s homes there are chances of missing the treatment…”(STS, Bengaluru district)

3.1.2. Response to Screening

- 1.

- Stigma and fear of disclosure: The healthcare providers shared that awareness of TB disease has garnered good attention in the urban area and that the rural area needs to evolve itself from stigmatizing the disease. Once the adults are diagnosed as TB patients, their children are immediately shifted to their relatives or neighboring houses. People possess the fear of disclosure as they fear being treated differently if others knew about their disease condition. Few patients ask the health staff to maintain confidentiality and the staff visit the patient’s household disguising as the patient’s relatives or friends, even a few patients have requested the health care staff not to visit their homes. Hence, screening pediatric contacts could be a missed opportunity. The health care providers generally convey information about the disease to the family in a sensitive manner based on the conduciveness and cultural context. People might face issues surrounding their relationships with regards to their jobs and marital conflict and end up losing their jobs and facing divorce.

“We directly do not start talking about TB. We indirectly talk about it (disease) that time they get convinced. If we suddenly start talking about TB, then there are chances that the family might get divided. We talk to patients first; through patients, we talk to the family…”(TBHV, Udupi district)

“According to our RNTCP, below 6 yrs we give prophylaxis but still there is a taboo. People will try to speak to us and tell ‘Sir we will shift the patient, we will say that no one was there in the house’ because they do not want to take the medication because of side effects…”(Medical officer, Udupi district)

“For people who live in a rented house, the owner can be problematic. Same family members do not know about the patient having TB. If the wife has TB, then the husband does not know. If daughter-in-law has TB, then mother-in-law does not know…”(STS, Bengaluru district)

“Some people ask us not to wear ID and if someone asks us then we tell we are the guests. These 2 things they restrict. Sometimes if the patient lives on the 2nd floor, then the patient comes down to meet us. In such cases, we ask the patient to come to the hospital…”(TBHV, Udupi district)

- 2.

- Non-availability of family members: Healthcare workers describe those patients who were less aware of the necessity of IPT and were more reluctant to participate in latent TB screening. Contact screening cannot be successfully achieved when all the members of the family are not present in the house during the visit of a healthcare provider for screening. Moreover, when the family is dependent on a person’s earnings, it is not feasible for that person to lose his earnings for the day. At times, patients might be the breadwinner of the family, and this compels them to continue working irrespective of their health conditions.

“Not everyone will be present. If a house has 5 members, we might be able to meet 3 members only. We meet only ladies as gents go to work. There are times when we will not be able to meet TB patients as well. Kids will be there since it is corona now…”(STS, Udupi district)

- 3.

- Healthcare staff not provided with due respect: The staff shared their experience of not being treated with due respect by the patients, especially if they have alcohol use disorders. Upon their visits, the health care providers were verbally abused by such patients and lack of co-operation further escalates the problem of screening the pediatric population at their houses.

“When I was working in K.R. Puram, a patient was co-infected with TB. When I went to their home and told even his wife will have to get tested. He had come running to hit me with a metal rod…”(STS, Bengaluru district)

“Chronic alcoholic patients are more in my TB unit. They scold us and try to hit us. They ask us not to come home…”(STS, Udupi district)

3.1.3. Challenges Faced during the Investigation

- 1.

- Challenges in the collection of samples—As explained by the healthcare providers, sample collection in children is a complex procedure especially when gastric lavage must be obtained. The staff shared their experience that parents generally object to such procedures. This is one of the potential challenges that hinder the contact investigation procedure. Other additional factors are sparsely available skills and health infrastructure.

“We can do CBNAAT procedure for Gastric lavage also but that is a difficult procedure because we must admit the child, we must do early morning aspiration. We cannot do it whenever we want. We should put a tube in the night and aspiration in the morning. If we put the tube in the morning, then secretion will move on to the duodenum. We will not get a proper sample that is a bit difficult procedure, Parents may not agree…”(Pediatrician, Udupi district)

- 2.

- Choosing private facilities over Government—Healthcare providers have witnessed parents being determined to provide the best of facilities for the well-being of their children in the notion that they opt for private healthcare facilities over the government. The follow-up of the child usually gets missed. The parents prefer to seek private health care services as they feel it is more secure and trustworthy since they believe that their health status is not revealed to the public health sector and hence, there are no follow-up visits by the health personnel. A private patient visits the hospital alone and does not take children to the hospital for evaluation and the opportunity for screening is missed.

“In private cases, it is difficult to follow up. We get the data extremely late from the private sector sometimes after a month. Private patients ask us not to visit their homes or do not want government medicines…”(STS, Udupi district)

- 3.

- Transportation issues to reach the hospital for investigation—The non-availability of a well-established transportation system for the patients to commute to the healthcare facilities is a major drawback for evaluation as there is no equitable distribution of health facilities at most places. Moreover, the transportation cost is an out-of-pocket expenditure for the patient. Hence, people are hesitant to make multiple visits for investigations. It is desired to have a point of care diagnostic test for the pediatric population that can be conducted at the residence.

“See from Kolluru they must come here and Maravanthe patients will have to go to Kundapura which is far. So, in between, if there is an X-ray facility it is better. If all the tests are done at one center it is more convenient rather than going to different places for different tests. At least one center with all the facilities every 20 km is better…”(STS, Udupi district)

“It is challenging to get TST done. If a test is available in the hospital, then it is easier for the patient as well. If they will have to travel to different places for a different test, then investigations will be delayed…”(STS, Bengaluru district)

- 4.

- Issue of the working hours—The population willing to access the public health facility is high in bigger cities such as Bengaluru since it is provided free of cost. However, patients do not want to wait for a longer duration period owing to their work commitments and expect a time slot for their visit.

“It is difficult to get the patient to the hospital. They ask us if the test is done for free, but if we must get a free test done then they do have to come at a specific time. Since parents work it gets delayed and they do not come when we ask them to come…”(TBHV, Bengaluru district)

3.1.4. Treatment Initiation

- 1.

- Anxiety due to long course of Chemoprophylaxis—Chemoprophylaxis is given for 6 months which is the same as the duration of the patient’s treatment. Parents tend to worry when long courses of antibiotics are given.

“If we say the child is positive, needs treatment they will be very anxious. That too when they see the tablet strips, they will be afraid to see so many drugs and big tablets. They will be worried since it must be given for six months. They will repeatedly ask if the child is positive? If the child needs so much treatment…”(Pediatrician, Udupi district)

- 2.

- Delay in getting the tests done—The healthcare staff noted a delay when parents spend money out of their pockets to get the investigations done in private labs. The suggested tests are freely available at select health facilities and many times the patients must shell out their money for such tests at private hospitals if these are not available. There remains a tendency among patients to delay such tests as they are not life-threatening. Bengaluru has a greater number of public and private health facilities in comparison with Udupi. While in Udupi, except the Udupi Taluka, other talukas are dependent mostly on public health facilities since there are only a few options of private health facilities.

“Some people give economic reasons to get the investigations done. They will have to get CXR, TST outside so it might get delayed.…”(TBHV, Bengaluru district)

- 3.

- Not visiting the hospital due to the fear of Coronavirus infection—The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has taken a toll over other infectious diseases since the focus has been shifted towards the COVID diagnosis and contact screening. People do not want to visit the hospital in the fear of contracting infections.

“People neglect the treatment or do not want to come to the hospital now as they have the fear of Corona. Earlier the problem was not being aware…”(ASHA, Udupi district)

3.1.5. Supervision and Monitoring

- 1.

- Lack of adherence record maintenance for Chemoprophylaxis—Adherence is stringently monitored only in the case of the patient but not in the case of a child administered with IPT. Hence, there are chances of missing doses.

“Adherence is not maintained in the Nikshay application (a web-based online portal for TB notification and patient care management in India). We will just mention the date when the medicines were given…”(STS, Bengaluru district)

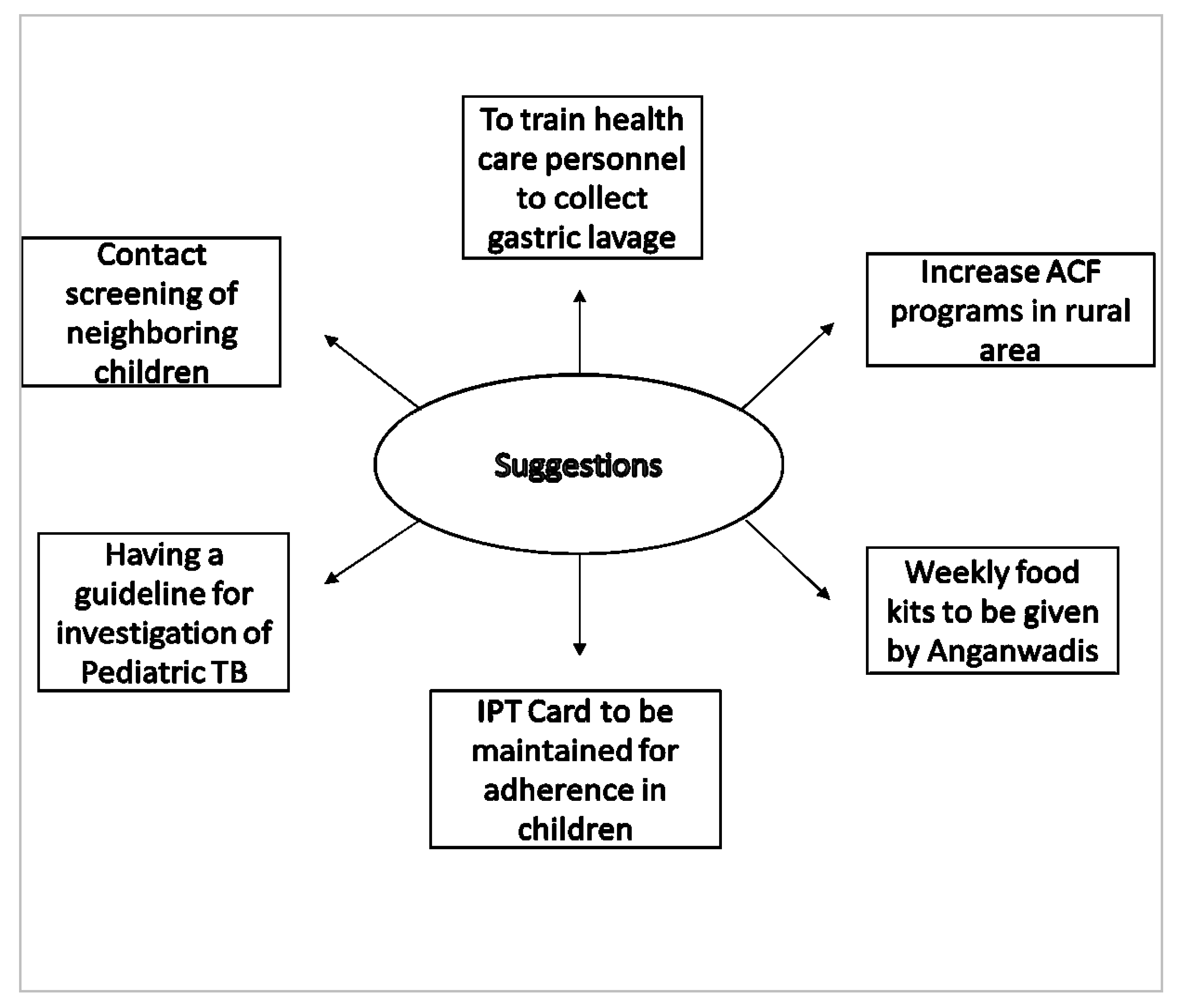

3.2. Suggestions

- 1.

- Evidence-based diagnosis is important for confirmation of pediatric TB. In practice, gastric lavage is being collected in pediatric age groups for which the child must be admitted to the hospital overnight but, in most cases, parents disagree with such elaborate procedures. As per the recently revised guidelines, collection of induced sputum is recommended. With consistent training for the practitioner at the peripheral level, challenges concerning sample collection can be resolved.

“There is little difficulty at implementation level mainly because gastric lavage is a challenging procedure, but revised guideline has a collection of induced sputum. But our public pediatricians are not yet trained for it. Even in the private sector, the diagnosis of pediatric TB is done clinically. Less importance is given to microbiological confirmation by obtaining a sputum sample. This is a major drawback both in the public and private sectors. We must tell them about the importance frequently. One fine day all the guidelines will be implemented…“(DTO)

- 2.

- Health workers describe that the awareness of various programmes must be given on various programmes and benefits under the government. Educating people about the disease and the symptoms will lead to better enrolment thereby early diagnosis.

“IEC should be there. We must guide them and educate them about the symptoms of HIV and TB. Awareness regarding every disease. Symptoms and spread of TB should be known. All the patients should be referred to the government. Now for TB, leprosy, and HIV, we have the best medicines here. The main thing is awareness about these diseases and facilities given by the government. Rural people should know. Automatically they will come. They will spread the word and guide other people also…”(Medical officer, Udupi district)

- 3.

- The NTEP is providing an incentive of nearly USD 7 per month as support for nutritious food under Nikshay Poshan Yojana for all the patients under the programme through a direct benefit transfer. Few patients have the opinion that rather than providing monetary support, nutritious food could have been distributed to patients and their families.

“Packets of protein-rich food can be provided. Perishables like milk and egg we cannot do anything, but protein-rich food provided by taluka level will help. Because Rs.500 they may spend it before going home also and some will have the habit of alcoholism. Usually, this disease is more prevalent in low socioeconomic status people so seeing that money they may use for something else also…”(Pediatrician, Udupi district)

- 4.

- Under the NTEP, only patient treatment adherence is maintained. Adherence to IPT can also be maintained for children. It can be done by updating the Nikshay application or by providing a treatment card.

“If a card is maintained for taking INH also then it will be more helpful…”(STS, Udupi district)

- 5.

- Children less than 6 years are examined for symptoms and investigated, while the age group above 6 years is only examined for symptoms. A systematic guideline based on the age criteria and latency of the disease can prevent the occurrence of the disease.

“We do not have a guideline for screening latent TB yet. For children above 6 years and adults, we can try to find out latent TB infection if included in the programme. Once we have guidelines for latent TB infection then everyone will be included, and evaluation can be carried out. For now, we do not have such guidelines. For children above 6 years old, they will have symptoms but one symptom, that is neglected is weight loss or no gain in weight by our staff. Weight loss is also one of the signs of TB not always pediatric contact presents with fever and cough. Because our staff will be mainly concentrating only on pediatric contact less than 6. This is the main problem in the programme concerning pediatric contact. For more than 6 years of age, we treat like other contacts which should not happen in my opinion…”(DTO)

- 6.

- In India, houses are placed closely, and the families have constant interaction with each other. Hence, it is important to screen not only the children living in the same household but also children living in the neighborhood as they are also in constant contact with the TB patient. Few of the healthcare professionals suggest that screening of neighboring children will certainly be helpful in the prevention of the disease which might otherwise appear in the future.

“I think one belt of surrounding house children also must be sent for contact screening, that should be improved…”(Medical officer, Udupi district)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global TB Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240013131 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- India TB Report. 2021. Available online: https://tbcindia.gov.in/showfile.php?lid=3587 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Marais, B.J.; Obihara, C.C.; Warren, R.; Schaaf, H.S.; Gie, R.P.; Donald, P.R. The burden of childhood tuberculosis: A public health perspective. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2005, 9, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, T.A. Challenges in Diagnosing Childhood Tuberculosis. Infect. Dis. J. IDJ 2016, 25, 26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan, S.; Rekha, B. Pediatric Tuberculosis: Global Overview and Challenges. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, S184–S194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, G.J.; Nhung, N.V.; Sy, D.N.; Hoa, N.L.; Anh, L.T.; Anh, N.T.; Hoa, N.B.; Dung, N.H.; Buu, T.N.; Loi, N.T.; et al. Household-Contact Investigation for Detection of Tuberculosis in Vietnam. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Recommendations for Investigating Contacts of Persons with Infectious Tuberculosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/77741/9789241504492_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Campbell, J.I.; Sandora, T.J.; Haberer, J.E. A scoping review of paediatric latent tuberculosis infection care cascades: Initial steps are lacking. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch-Moverman, Y.; Mantell, J.E.; Lebelo, L.; Howard, A.A.; Hesseling, A.C.; Nachman, S.; Frederix, K.; Maama, L.B.; El-Sadr, W.M. Provider attitudes about childhood tuberculosis prevention in Lesotho: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pothukuchi, M.; Nagaraja, S.B.; Kelamane, S.; Satyanarayana, S.; Shashidhar; Babu, S.; Dewan, P.; Wares, F. Tuberculosis Contact Screening and Isoniazid Preventive Therapy in a South Indian District: Operational Issues for Programmatic Consideration. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nikshay Reports. Available online: https://reports.nikshay.in/Reports/TBNotification (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- WHO. Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis: Systematic Screening for Tuberculosis Disease. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/340255/9789240022676-eng.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Karnataka Population Sex Ratio in Karnataka Literacy Rate Data. 2011. Available online: https://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/karnataka.html (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belgaumkar, V.; Chandanwale, A.; Valvi, C.; Pardeshi, G.; Lokhande, R.; Kadam, D.; Joshi, S.; Gupte, N.; Jain, D.; Dhumal, G.; et al. Barriers to screening and isoniazid preventive therapy for child contacts of tuberculosis patients. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2018, 22, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.R.; Kharate, A.; Bhat, P.; Kokane, A.M.; Bali, S.; Sahu, S.; Verma, M.; Nagar, M.; Kumar, A.M. Isoniazid Preventive Therapy among Children Living with Tuberculosis Patients: Is It Working? A Mixed-Method Study from Bhopal, India. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2017, 63, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Banu Rekha, V.V.; Jagarajamma, K.; Wares, F.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Swaminathan, S. Contact screening and chemoprophylaxis in India’s Revised Tuberculosis Control Programme: A situational analysis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2009, 13, 1507–1512. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19919768 (accessed on 18 May 2021). [PubMed]

- Shivaramakrishna, H.R.; Frederick, A.; Shazia, A.; Murali, L.; Satyanarayana, S.; Nair, S.A.; Kumar, A.M.; Moonan, P. Isoniazid preventive treatment in children in two districts of South India: Does practice follow policy? Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2014, 18, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, R.; Khayyam, K.U.; Singla, N.; Anand, T.; Nagaraja, S.B.; Sagili, K.D.; Sarin, R. Nikshay Poshan Yojana (NPY) for tuberculosis patients: Early implementation challenges in Delhi, India. Indian J. Tuberc. 2020, 67, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chawla, K.; Burugina Nagaraja, S.; Siddalingaiah, N.; Sanju, C.; Shenoy, V.P.; Kumar, U.; Das, A.; Hazra, D.; Shastri, S.; Singarajipur, A.; et al. Challenges Perceived by Health Care Providers for Implementation of Contact Screening and Isoniazid Chemoprophylaxis in Karnataka, India. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6030167

Chawla K, Burugina Nagaraja S, Siddalingaiah N, Sanju C, Shenoy VP, Kumar U, Das A, Hazra D, Shastri S, Singarajipur A, et al. Challenges Perceived by Health Care Providers for Implementation of Contact Screening and Isoniazid Chemoprophylaxis in Karnataka, India. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2021; 6(3):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6030167

Chicago/Turabian StyleChawla, Kiran, Sharath Burugina Nagaraja, Nayana Siddalingaiah, Chidananda Sanju, Vishnu Prasad Shenoy, Uday Kumar, Arundathi Das, Druti Hazra, Suresh Shastri, Anil Singarajipur, and et al. 2021. "Challenges Perceived by Health Care Providers for Implementation of Contact Screening and Isoniazid Chemoprophylaxis in Karnataka, India" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 6, no. 3: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6030167

APA StyleChawla, K., Burugina Nagaraja, S., Siddalingaiah, N., Sanju, C., Shenoy, V. P., Kumar, U., Das, A., Hazra, D., Shastri, S., Singarajipur, A., & Reddy, R. C. (2021). Challenges Perceived by Health Care Providers for Implementation of Contact Screening and Isoniazid Chemoprophylaxis in Karnataka, India. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 6(3), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6030167