Strategies Used for Implementing and Promoting Adherence to Antibiotic Guidelines in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

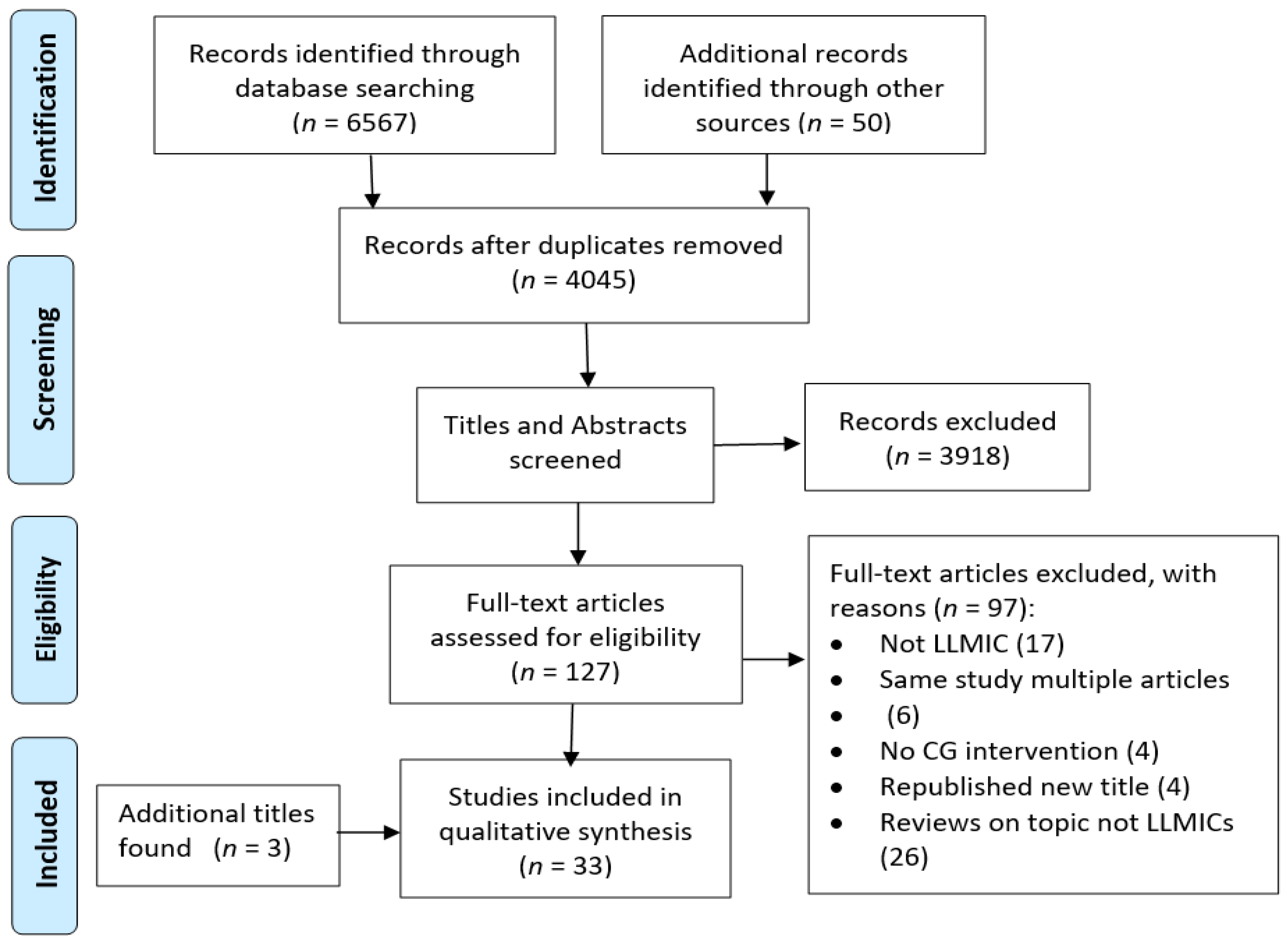

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Terminology

2.2. Search Methods for Identification of Studies

2.3. Study Screening and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion

- Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cluster RCTs, controlled clinical trials, quasi experimental studies, controlled pre- and post-intervention studies (CPPI), pre- and post-intervention studies (PPI) and interrupted time series (ITS) studies.

- The LLMICs include those listed by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Development Assistance Committee for 2018 to 2020 [22].

- Health workers in LLMICs who prescribe antibiotic therapy.

- Patients from all age groups in LLMICs who receive antibiotic therapy.

- Any strategy which was aimed at promoting CG uptake or compliance for the purpose of improving rational antibiotic prescription.

- Studies published in English language between 2000 and July 2020.

- The primary outcomes included health worker performance based on appropriateness of prescribing including:

- ■

- Correct agent, correct dose, correct duration, correct route of administration or time of administration.

- ■

- Proportion of antibiotics prescribed in accordance with CG.

- ■

- Consumption of antibiotics expressed as defined daily doses per 100 or 1000 patient days.

- ■

- Patient encounters with an antibiotic.

- ■

- Patient outcomes—mortality and hospital re-admission rates.

- ■

- Adverse effects impacting patient outcomes.

2.3.2. Exclusion

- Commentaries, conference proceedings and literature reviews

- Languages other than English.

2.4. Study Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction Method

2.6. Data Synthesis and Presentation

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies

3.1.1. Search Results and Study Quality

3.1.2. Settings and Study Participants

3.1.3. Clinical Guidelines

3.2. Interventions

3.2.1. Strategies Used

3.2.2. Organisational Strategies

3.2.3. Capacity-Building Strategies

3.2.4. Monitoring and Review Strategy

3.2.5. Clinical Decision Support Systems

3.2.6. Persuasive Strategies

3.3. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klein, E.; Van Boeckeld, T.; Martineza, E.; Panta, S.; Gandraa, S.; Levine, S.; Goossensh, H.; Laxminarayana, R. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E3463–E3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509763 (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Ombelet, S.; Ronat, J.; Walsh, T.; Yansouni, C.; Cox, J.; Vlieghe, E.; Martiny, D.; Semret, M.; Vandenberg, O.; Jacobs, J. Clinical bacteriology in low-resource settings: Today’s solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, S1473–S3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, M.; Stewardson, A.; Naidu, R.; Coghlan, B.; Jenney, J.; Kepas, A.; Lavu, E.; Munamua, A.; Peel, T.; Sahai, S.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance in the Pacific Island countries and territories. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Healthcare Facilities in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A WHO Practical Toolkit. Available online: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo) (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Olayemi, E.; Asare, E.; Benneh-Akwasi Kuma, A. Guidelines in lower-middle income countries. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 177, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. In Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust; Graham, R., Mancher, M., Miller Wolman, D., Greenfield, S., Steinberg, E., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ament, S.; de Groot, J.; Maessen, J.; Dirkson, C.; van de Weijden, T.; Kleijinen, J. Sustainability of professionals’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines in medical care: A systematic review. BMJ Open Qual. 2015, 5, e008073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleuren, M.; Van Dommelen, P.; Dunnink, T. A systematic approach to implementing and evaluating clinical guidelines: The results of fifteen years of preventive child health care guidelines in the Netherlands. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 136–137, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, J.; Eccles, M.; Thomas, R.; MacLennan, G.; Ramsay, C.; Fraser, C.; Vale, L. Toward evidence-based quality improvement. Evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966–1998. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21 (Suppl. S2), S14–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickell, K.D.; Mangale, D.I.; Tornberg-Belanger, S.N.; Bourdon, C.; Thitiri, J.; Timbwa, M.; Njirammadzi, J.; Voskuijl, W.; Chisti, M.J.; Ahmed, T.; et al. A mixed method multi-country assessment of barriers to implementing pediatric inpatient care guidelines. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francke, A.; Smit, M.; de Veer, A.; Mistiaen, P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: A systematic meta-review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2008, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.; Peason, T.; Bennett, G.; Cushman, W.; Gaziano, T.; Gorman, P.; Handler, J.; Krumholz, H.; Kushner, R.; MacKenzie, T.; et al. Clinical practice guideline implementation strategies: A summary of systematic reviews by the NHLBI Implementation Science Work Group. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 1076–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, P.A.; Pujat, D. Implementing Practice Guidelines for Appropriate Antimicrobial Usage: A Systematic Review. Med. Care 2001, 39, II55–II69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque, F.M.T.; Herdeiro, M.; Soares, S.; Rodrigues, A.; Breitenfeld, L.; Figueiras, A. Educational interventions to improve prescription and dispensing of antibiotics: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grol, R. Successes and Failures in the Implementation of Evidence-Based Guidelines for Clinical Practice. Med. Care 2001, 39 (Suppl. S2), 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squires, J.; Sullivan, K.; Eccles, M.; Worswick, J.; Grimshaw, J. Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single-component interventions in changing health-care professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, s13012–s13014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimshaw, J.M.; Thomas, R.E.; MacLennan, G.; Fraser, C.; Ramsay, C.R.; Vale, L.; Whitty, P.; Eccles, M.P.; Matowe, L.; Shirran, L.; et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol. Assess. 2004, 8, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijck, C.; Vliegheb, E.; Cox, J. Antibiotic stewardship interventions in hospitals in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018, 96, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Grande, A.; Hogazeil, H.; Haaijer-Ruskamp, F. Intervention research in rational use of drugs: A review. Health Policy Plan. 1999, 14, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development Assistance Committee. DAC List of ODA Recipients: Effective for Reporting on 2018, 2019 and 2020 Flows. Available online: DAC_List_ODA_Recipients2018to2020_flows_En.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Downs, S.; Black, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, C.; Matowe, L.; Grilli, R.; Grimshawe, J.; Thomas, R. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: Lessons from two systematic reviews of behaviour change strategies. Int. J. Health Technol. Assess. Health Care 2003, 19, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; López-López, J.A.; Becker, B.J.; Davies, S.R.; Dawson, S.; Grimshaw, J.M.; McGuinness, L.A.; Moore, T.H.M.; Rehfuess, E.A.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesising quantitative evidence in systematic reviews of complex health interventions. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4 (Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Biostats 1995, 536, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, M.H.; Thomson, H. The effect direction plot revisited: Application of the 2019 Cochrane Handbook guidance on alternative synthesis methods. Res. Synth Methods 2021, 12, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dizon, J.M.; Machingaidze, S.; Grimmer, K. To adopt, to adapt, or to contextualise? The big question in clinical practice guideline development. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, s13104–s13116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Taxonomy. 2015. Available online: http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Bernasconi, A.; Crabbe’, F.; Raab, M.; Rossi, R. Can the use of digital algorithms improve quality care? An example from Afghanistan. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Heller, R.; Smith, A.; Milly, A. Impact of a training intervention on use of antimicrobials in teaching hospitals. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2009, 3, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chowdhury, A.K.; Khan, M.O.F.; Matin, M.A.; Begum, K.; Galib, M.A. Effect of standard treatment guidelines with or without prescription audit on prescribing for acute respiratory tract infection and diarrhoea in some Thana health complexes of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Med. Res. Counc. Bull. 2007, 33, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, F.; Ball, R.L.; Khatun, S.; Ahmed, M.; Kache, S.; Chisti, M.J.; Sarker, S.A.; Maples, S.D.; Pieri, D.; Vardhan Korrapati, T.; et al. Evaluation of a Smartphone Decision-Support Tool for Diarrheal Disease Management in a Resource-Limited Setting. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, H.; Gerth-Guyette, E.; Shakil, S.; Alom, K.; Abu-Haydar, E.; D’Rozario, M.; Tariquijaman, M.; Arifeen, S.; Ahmed, T. Evaluating the use of job aids and user instructions to improve adherence for the treatment of childhood pneumonia using amoxicillin dispersible tablets in a low-income setting: A mixedmethod study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamer, S.; Soad, F.; Amr, K.; Amany, E.K.; Ghada, I.; Mariam, A.; Ehab, A.; Ahmad, H.; Ossama, A.; Elham, E.; et al. Antimicrobial stewardship to optimize the use of antimicrobials for surgical prophylaxis in Egypt: A multicenter pilot intervention study. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2015, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebretekle, G.B.; Mariam, D.H.; Taye, W.A.; Fentie, A.M.; Degu, W.A.; Alemayehu, T.; Beyene, T.; Libman, M.; Fenta, T.G.; Yansouni, C.P.; et al. Half of prescribed antibiotics are not needed: A pharmacist led antmicrobial stewardship intervention and clinical outcomes in a referral hospital in Ethiopia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, H.S.; Shaikh, F.A.; Deepak, R.; Poddutoor, P.K.; Chirla, D. Antimicrobial Justification form for Restricting Antibiotic Use in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Indian Pediatr. 2016, 53, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandy, S.J.; Naik, G.S.; Charles, R.; Jeyaseelan, V.; Naumova, E.N.; Thomas, K.; Lundborg, C.S. The impact of policy guidelines on hospital antibiotic use over a decade: A segmented time series analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehn Lunn, A. Reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in upper respiratory tract infection in a primary care setting in Kolkata, India. BMJ Open Qual. 2018, 7, e000217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaggi, N.; Sissodia, P.; Sharma, L. Control of Multidrug Resistant Bacteria in a Tertiary Care Hospital in India. 2012. Available online: http://www.aricjournal.com/content/1/1/23 (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Patel, S.; Vasavada, H.; Damor, P.; Parmar, V. Impact of antibiotic stewardship strategy on the outcome of non-critical hospitalized children with suspected viral infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 2016, 8, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Menon, V.P.; Mohamed, Z.U.; Kumar, V.A.; Nampoothiri, V.; Sudhir, S.; Moni, M.; Dipu, T.S.; Dutt, A.; Edathadathil, F.; et al. Implementation and Impact of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at a Tertiary Care Center in South India. Open Forum Infect. Dis 2019, 6, ofy290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattal, C.; Khanna, S.; Goel, N.; Oberoi, J.; Rao, B. Antimicrobial Prescribing Patterns of Surgical Speciality in a Tertiary Care Hospital in India: Role of Persuasive Intervention for Changing Antibiotic Prescription Behaviour. Indian J. Microbiol. 2017, 35, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, U.; Keuter, M.; van Asten, H.; Van Den Broek, P. Optimizing antibiotic usage in adults admitted with fever by a multifaceted intervention in an Indonesian governmental hospital. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2008, 13, 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murni, I.K.; Duke, T.; Kinney, S.; Daley, A.J.; Soenarto, Y. Reducing hospital-acquired infections and improving the rational use of antibiotics in a developing country: An effectiveness study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, A.M.; Wanyoro, A.K.; Mwangi, J.; Juma, F.; Mugoya, I.K.; Scott, J.A. Changing use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in Thika Hospital, Kenya: A quality improvement intervention with an interrupted time series design. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korom, R.R.; Onguka, S.; Halestrap, P.; McAlhaney, M.; Adam, M.B. Brief educational interventions to improve performance on novel quality metrics in ambulatory settings in Kenya: A multi-site pre-post effectiveness trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opondo, C.; Ayieko, P.; Ntoburi, S.; Wagai, J.; Opiyo, N.; Irimu, G.; Allen, E.; Carpenter, J.; English, M. Effect of a multi-faceted quality improvement intervention on inappropriate antibiotic use in children with non-bloody diarrhoea admitted to district hospitals in Kenya. BMC Pediatrics 2011, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.; Soukaloun, D.; Soumphonphakakdy, B.; BDuke, T. Implementing WHO hospital guidelines improves quality of paediatric care in central hospitala in Lao PDR. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2015, 20, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlstrom, R.; Kounnavong, S.; Sisounthone, B.; Phanyanouvong, A.; Southammavong, T.; Eriksson, B.; Tomson, G. Effectiveness of feedback for improving case management of malaria, diarrhoea and pneumonia—a randomized controlled trial at provincial hospitals in Lao PDR. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2003, 8, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, R.D.; Zervos, M.; Kaljee, L.M.; Shrestha, B.; Maki, G.; Prentiss, T.; Bajracharya, D.; Karki, K.; Joshi, N.; Rai, S.M. Evaluation of a Hospital-Based Post-Prescription Review and Feedback Pilot in Kathmandu, Nepal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.; Samir, K.C.; Baltussen, R.; Kafle, K.K.; Bishai, D.; Niessen, L. Practical approach to lung health in Nepal: Better prescribing and reduction of cost. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2006, 11, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Hussein, K.; Manasia, R.; Samad, A.; Salahuddin, N.; Zafar, A.; Hoda, M.Q. Impact of antibiotic restriction on broad spectrum antibiotic usage in the ICU of a developing country. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2007, 57, 484–487. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, D.; Bugg, I.; Hamilton, D.; Bugg, I. Improving antimicrobial stewardship in the outpatient department of a district general hospital in Sierra Leone. BMJ Open Qual. 2018, 7, e000495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillekeratne, L.; Baghchevan, V.; Nagahawatte, A.; Vidanagama, D.; Devasiri, V.; Arachchi, W.; Kurukulasooriya, R.; De Silva, A.; Østbye, T.; Reller, M.; et al. Use of Rapid Influenza Testing to Reduce Antibiotic Prescriptions among Outpatients with Influenza-Like Illness in Southern Sri Lanka. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 93, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, A.; Eltayeb, I.; Baraka, O. Changing antibiotics prescribing practices in health centers of Khartoum State, Sudan. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 62, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keitel, K.; Kagoro, F.; Samaka, J.; Masimba, J.; Said, Z.; Temba, H.; Mlaganile, T.; Sangu, W.; Rambaud-Althaus, C.; Gervaix, A.; et al. A novel electronic algorithm using host biomarker point-of-care tests for the management of febrile illnesses in Tanzanian children (e-POCT): A randomized, controlled non-inferiority trial. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, A.; Rambaud-Althaus, C.; Samaka, J.; Faustine, A.; Perri-Moore, S.; Swai, N.; D’Acremont, V. New Algorithm for Managing Childhood Illness Using Mobile Technology (ALMANACH): A controlled non-inferiority study on clinical outcome and antibiotic use in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalker, J. Improving antibiotic prescribing in Hai Phong Province, Viet Nam: The “antibiotic-dose” indicator. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Do, N.T.T.; Ta, N.T.; Tran, N.; Than, H.; Vu, B.; Hoang, L.; Van Doorn, H.; Vu, D.; Cals, J.; Chandna, A.; et al. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing to reduce inappropriate use of antibiotics for non-severe acute respiratory infections in Vietnamese primary health care: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Glob. Health 2016, 4, E633–E641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, N.Q.; Thi Lan, P.; Phuc, H.D.; Chuc, N.T.K.; Stalsby-Lundborg, C. Antibiotic prescribing and dispensing of acute respiratory infections in children: Effectiveness of a multi-faceted intervention for health-care providers in Vietnam. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1327638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trap, B.; Todd, C.H.; Moore, H.; Laing, R. The impact of supervision on stock management and adherence to treatment guidelines: A randomized controlled trial. Health Policy Plan. 2001, 16, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, M.; Guerin, M.; Grimmer-Somers, K. The effectiveness of clinical guideline implementation strategies—a synthesis of systematic review findings. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2008, 14, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, K.; Wood, H.; Schneider, C.; Cliffod, R. Effectiveness of implementation strategies for clinical guidelines to community pharmacy: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hecke, O.; Butler, C.; Mendelson, M.; Tonkin-Crine, S. Introducing new point-of-care tests for common infections in publicly funded clinics in South Africa: A qualitative study with primary care clinicians. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Essential In Vitro Diagnostics List (IDL) Focussing on the Need to Improve Access to Health Systems. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311567/9789241210263-eng.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Poushter, J.; Pew Research Centre. Smartphone Ownership and Internet Usage Continues to Climb in Emerging Economies. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2016/02/22/smartphone-ownership-and-internet-usage-continues-to-climb-in-emerging-economies/ (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Doyle, M. Implementing an antimicrobial stewardship programme. In Antimicrobial Stewardship; Laundy, M., Gilchrist, M., Whitney, L., Eds.; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kredo, T.; Bernhardsson, S.; Machingaidze, S.; Young, T.; Louw, Q.; Ochodo, E.; Grimmer, K. Guide to clinical practice guidelines: The current state of play. Int. J. Qual. Healthc. 2016, 28, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaoye, O.; Tuck, C.; Khor, W.P.; McMenamin, R.; Hudson, L.; Northall, M.; Panford-Quainoo, E.; Asima, D.M.; Ashiru-Oredope, D. Improving Access to Antimicrobial Prescribing Guidelines in 4 African Countries: Development and Pilot Implementation of an App and Cross-Sectional Assessment of Attitudes and Behaviour Survey of Healthcare Workers and Patients. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantoja, T.; Opiyo, N.; Lewin, S.; Paulsen, E.; Ciapponi, A.; Wiysonge, C.; Herrera, C.; Rada, G.; Panaloza, B.; Dudley, L.; et al. Implementation strategies for health systems in low-income countries: An overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Libr. Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year) | Titles | Country | Description of Context | Participants | Study Length; Outcome Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised Control Trials | |||||

| Keitel, K. et al. (2017) [57] | A novel electronic algorithm using host biomarker point-of-care tests for the management of febrile illnesses in Tanzanian children (e-POCT): A randomized, controlled non-inferiority trial. | Tanzania | Outpatient departments at 3 district hospitals and 6 health centre clinics in Dar es Salaam; in parallel, routine care documented in 2 additional health centres. | 3716 paediatric patients: age 24 to 59 months with acute febrile illness (≤7 days fever ≥37.5 °C temperature): ALMANACH plus e-POCT: 1586 (intervention) and ALMANACH alone: 1583 (control); 547 in parallel control. | • 13 months long; • No. clinical failures day 7; • No. prescriptions day 0; • No. primary referrals. |

| Do, N.T.T. et al. (2016) [60] | Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing to reduce inappropriate use of antibiotics for non-severe acute respiratory infections in Vietnamese primary health care: a randomised controlled trial. | Vietnam | 9 urban polyclinics and the outpatient clinic of a rural district general hospital within a 60 km radius of Hanoi. | 2037 patients presenting with non-severe ARTIs: 1017 intervention and 1019 control group. | • 15 months long; • No. prescriptions within 14 days; • Antibiotics in urine days 3/4/5. |

| Shao, A.F. et al. (2015) [58] | New Algorithm for Managing Childhood Illness Using Mobile Technology (ALMANACH): A controlled non-inferiority study on clinical outcome and antibiotic use in Tanzania. | Tanzania | Two pairs of primary healthcare facilities, 1 pair in urban Dar es Salaam and 1 pair in rural Morogoro with similar catchment populations and services. | Paediatric patients 2 to 59 months; Total 842 in intervention (ALMANACH) and 623 in control group. Illness not reported. | • 7 months long; • No. prescriptions day 0; • Cured day 7. |

| Trap, B. et al. (2001) [62] | The impact of supervision on stock management and adherence to treatment guidelines: a randomized controlled trial. | Zimbabwe | 62 rural health centres across 7 of the 8 Provinces randomized into 3 groups: 21 to stock management; 23 to standard treatment guideline and 18 to a control group. | 10 pharmacy officers and 1–2 nursing staff per rural health centre. Illness: non-bloody diarrhoea; ARTIs, genital ulcer. | • 12 months long; • No. correct drug, dose, duration. |

| Wahlstrom, R. et al. (2003) [50] | Effectiveness of feedback for improving case management of malaria, diarrhoea and pneumonia—a randomized controlled trial at provincial hospitals in Lao PDR. | Lao PDR | 8 Provincial hospitals in the Vientiane Municipality—24 departments matched into 4 pairs of 3 departments: internal medicine, paediatrics and outpatients and randomised to intervention and control groups | Prescribers: doctors and medical assistants: 53 in intervention and 69 in control. Illness: diarrhoeal disease, malaria, pneumonia. | • 12 months long; • Changes in key CG indicator scores. |

| Cluster Randomised Control Trials | |||||

| Awad, A.I. et al. (2006) [56] | Changing antibiotics prescribing practices in health centres of Khartoum State, Sudan. | Sudan | 20 health centres in Khartoum State: 1 control and 3 intervention groups. | 1800 patient encounters; 1 general practitioner and 1 or 2 medical officers per health centre. Illness not reported. | • 6 months long; • % Encounters with antibiotics. |

| Chowdhury, A.K. et al. (2007) [32] | Effect of Standard Treatment Guidelines with or without Prescription Audit on Prescribing for Acute Respiratory Tract Infection and Diarrhoea in some Thana Health Complexes of Bangladesh. | Bangladesh | 24 randomly selected health complexes from 120 Thana health complexes, primary health centres in Dakar district: 2 groups of 8 in intervention and 1 group of 8 in control. | 6000 prescriptions collected baseline and total number post-intervention not reported. Illness: ARTIs and diarrhoeal disease. | • 7 months long; • % Encounters with antibiotics. |

| Hoa, N.Q. et al. (2017) [61] | Antibiotic prescribing and dispensing of acute respiratory infections in children: Effectiveness of a multi-faceted intervention for health-care providers in Vietnam. | Vietnam | A rural 150-bed district hospital, 3 regional polyclinics and 32 commune health clinics in Bavi district north of Hanoi; randomised to 2 arms: STIs and ARTIs. | Total of 299 health care practitioners: 139 pre- and 160 post-intervention. Illness: mild ARTIs. Total prescriptions: 1279 intervention; 742 control. | • 7 months long; • Mean KAP scores; • % Appropriate prescription. |

| Opondo, C. et al. (2011) [48] | Effect of a multi-faceted quality improvement intervention on inappropriate antibiotic use in children with non-bloody diarrhoea admitted to district hospitals in Kenya. | Kenya | 8 district hospitals randomised into 2 groups of 4 across 4 Provinces. | 130 health workers in 4 intervention group hospitals and 135 health workers in: 4 control; 1160 admission records of children < 5years old with non-bloody diarrhoea not requiring antibiotics. | • 36 months long; • No. inappropriate prescriptions received. |

| Shrestha, N. et al. (2006) [52] | World Health Organization’s (WHO) ractical approach to lung health in Nepal: better prescribing and reduction of cost. | Nepal | 40 primary health facilities randomized into 19 control groups and 21 intervention groups. | 84 patients pre- and 67 post-intervention in the control group and 155 pre- and 101 post-intervention in the intervention group. Illness: lung disease. | • 12 months long; • % Encounters with antibiotics; • Adherence to WHO’s PAL. |

| Interrupted Time Series Studies | |||||

| Aiken, A.M. et al. (2013) [46] | Changing use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in Thika Hospital, Kenya: a quality improvement intervention with an interrupted time series design. | Kenya | Public hospital with 300 beds 50 km northeast of Nairobi performing 300 surgical procedures monthly. | 3343 patients undergoing surgical procedures involving overnight stay; 6 surgeons and 16 to 20 junior doctors and clinical officers. Illness: SSIs | • 16 months long; • 66 data points • % Operations with correct prophylaxis. |

| Chalker, J. (2001) [59] | Improving antibiotic prescribing in Hai Phong Province, Viet Nam: the antibiotic-dose indicator. | Vietnam | 217 commune health stations in 12 Provincial Districts. | 6270 records examined; total number health workers not reported. Illness not reported. | • 18 months long; • 6 datapoints • % Encounters with antibiotics; • % Receiving adequate dose. |

| Chandy, S.J. et al. (2014) [38] | The Impact of Policy Guidelines on hospital antibiotic use over a decade: A segmented time series analysis. | India | 2140-bed teaching hospital in south India serving 6000 outpatients per day with Drugs and Therapeutics Committee and Formulary Sub-Committee. | All inpatients in the hospital over a 10-year period prescribed an antibiotic. Illness: not reported. | • 10 years long; • 110 datapoints • DDD per 100 bed-days. |

| Hadi, U. et al. (2008) [44] | Optimizing antibiotic usage in adults admitted with fever by a multifaceted intervention in an Indonesian governmental hospital. | Indonesia | Internal medicine department of a 1432-bed teaching hospital with 60,000 annual admissions. | 501 patients’ consultations within first 24 hours of admission; 155 clinicians. Illness: fever. | • 1 year long; • 28 datapoints • DDD per 100 bed-days. |

| Wattal, C. et al. (2017) [43] | Antimicrobial prescribing patterns of surgical speciality in a tertiary care hospital in India: Role of persuasive intervention for changing antibiotic prescription behaviour. | India | 45 clinical units across a 675-bed tertiary hospital in New Delhi. | 90 clinicians, all prescribers across all specialities. Illness: SSIs. | • 9 months long; • DDD per 100 bed-days. |

| Quasi-Experimental Studies | |||||

| Gebretekle, G.B. et al. (2020) [36] | Half of prescribed antibiotics are not needed: a pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship intervention and clinical outcomes in a referral hospital in Ethiopia. | Ethiopia | Referral and teaching hospital in Addis Ababa, with 800 beds (191 paediatric beds) | 1264 prescriptions (707 patients) intervention and 1138 (402 patients) post-intervention. Illness: sepsis, febrile neutropenia, CA & HA pneumonia. | • 15 months long; • Mean no. days patient receives antibiotic; • Days of therapy per 1000 bed-days. |

| Sarma, H. et al. (2019) [34] | Evaluating the use of job aids and user instructions to improve adherence for the treatment of childhood pneumonia using amoxicillin dispersible tablets in a low-income setting: a mixed method study. | Bangladesh | Community health centres and Union health and family welfare centres in Ghatail and Kalihati sub-districts: 55 and 17; 54 and 18, respectively | 94 health workers: 56 in intervention group; 38 in control group. Illness: pneumonia. | • 4 months long; • % Receiving appropriate antibiotic prescription & treatment. |

| Controlled Pre- and Post-intervention Studies | |||||

| Akter, S.F. et al. (2009) [31] | Impact of a training intervention on use of antimicrobials in teaching hospitals. | Bangladesh | 3 medical college hospitals providing tertiary care and referral to secondary and primary level hospitals: 1 intervention and 2 control. | 3466 paediatric patients receiving antibiotics: 2171 pre- and 1295 post-intervention. Illness: pneumonia, diarrhoeal disease. | • 12 months long; • % Receiving appropriate antibiotic prescription & treatment. |

| Bernasconi, A. et al. (2018) [30] | Can the use of digital algorithms improve quality care? An example from Afghanistan. | Afghanistan | 3 Afghan Red Cross Society health centres in Kabul Province. | 767 paediatric patient: age 2–5 years.: 404 pre- and 362 post-intervention. Illness: acute childhood illness | • 16 months long; • % Receiving appropriate antibiotic prescription & treatment. |

| Haque, F. et al. (2017) [33] | Evaluation of a Smartphone Decision-Support Tool for Diarrheal Disease Management in a Resource-Limited Setting. | Bangladesh | Main district hospital and a sub-district hospital (1 0f 8) in the rural northern district of Nekrokona, a resource-limited area with a population of 2.2 million. | 85 clinicians; 841 patients ≥2 months with diarrheal disease without comorbidities or severe malnutrition: 325 pre- and 516 post-intervention. | • 3 months long; • % Appropriate antibiotic prescription. |

| Pre- and Post-intervention Studies | |||||

| Bhullar, H.S. et al. (2016) [37] | Antimicrobial Justification form for Restricting Antibiotic Use in a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit. | India | 14-bed paediatric intensive care unit in Children’s Hospital, Hyderabad. | 1693 paediatric patients: 872 pre- and 821 post-intervention. Illness not reported. | • 21 months long; • % Receiving restricted antibiotics (RA). |

| Dehn Lunn, A. (2018) [39] | Reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in upper respiratory tract infection in a primary care setting in Kolkata. | India | Outreach primary care clinics in rural Kolkata and West Bengal serving homeless and slum communities. | 311 patients: 222 pre- and 92 post-intervention; 10 doctors, pharmacists, and other health workers. Illness: URTIs. | • 4 months long; • % Encounters with antibiotics. |

| Gray, A.Z. et al. (2015) [49] | Implementing WHO hospital guidelines improves quality of paediatric care in central hospital in Lao PDR. | Lao PDR | 3 hospitals in Vientiane with a total 140-beds and a paediatric ICU in each hospital. | 91 clinicians; 681 patients: 356 pre- and 325 post-intervention. Illness: pneumonia, diarrhoeal disease, LBW. | • 15 months long; • Mean Key CG indicator scores. |

| Hamilton, D. et al. (2018) [54] | Improving antimicrobial stewardship in the outpatient department of a district general hospital in Sierra Leone. | Serra Leone | Outpatient department of Medusa Hospital, a rural district general hospital. | 128 patient’s baseline; 139 phase 1; 128 phase 2. ASP. | • 6 months long; • % Correct drug, dosage, duration. |

| Jaggi, N. et al. (2012) [40] | Control of multidrug resistant bacteria in a tertiary care hospital in India. | India | A 300-bed tertiary care private hospital in Gurgaon, Haryana. | 28,971 clinical samples cultured. Illness: HAIs | • 36 months long; • DDD per 1000 bed-days. |

| Joshi, R.D. et al. (2019) [51] | Evaluation of a Hospital-Based Post-Prescription Review and Feedback Pilot in Kathmandu, Nepal. | Nepal | 125-bed tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu Valley. | 451 patients’ charts reviewed: 221 baseline and 230 post-intervention. ASP. | • 24 months long; • % Appropriate antibiotic therapy |

| Korom, R.R. et al. (2017) [47] | Brief educational interventions to improve performance on novel quality metrics in ambulatory settings in Kenya: a multi-site pre-post effectiveness trial. | Kenya | 2 semi-urban primary health centres in Nairobi. | 24 clinical officers; 475 charts of female patients aged 14 to 49 years. Illness: UTIs. | • 12 months long; • % Encounters with antibiotics; • % Appropriate antibiotic therapy. |

| Murni, I.K. et al. (2015) [45] | Reducing hospital-acquired infections and improving the rational use of antibiotics in a developing country: an effectiveness study. | Indonesia | Referral teaching hospital with 39-bed paediatric ward and 9-bed paediatric intensive care in Yogyakarta servicing 2.4 million people. | 2646 paediatric inpatients with more than 48 hours hospital stay: 1227 pre- and 1419 post-intervention. Illness: HAIs. | • 26 months long; • Incidence of HAIs; • % Exposed to inappropriate antibiotics. |

| Patel, S. (2016) [41] | Impact of antibiotic stewardship strategy on the outcome of non-critical hospitalized children with suspected viral infection. | India | Paediatric ward of Shardaben Hospital, NHL Medical College, Ahmedabad. | 1760 non-critical paediatric patients with suspected viral infections. Illness: suspected viral infection. | • 44 months long; • % RA used appropriately. |

| Singh, S. et al. (2019) [42] | Implementation and impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program at a tertiary care centre in South India. | India | Academic tertiary care referral hospital in Kerala with 1300 beds and 254 beds across 13 ICUs. | 4613 patients received at least 1 antibiotic during inpatient stay. ASP. | • 23 months long; • Mean length of inpatient days; |

| Siddiqui, S. et al. (2007) [53] | Impact of antibiotic restriction on broad spectrum antibiotic usage in the ICU of a developing country | Pakistan | Tertiary care teaching hospital with 12-bed ICU in Karachi. | Sample size not reported. Illness: HAIs. | • 6 months long; • % RA prescribed as per CG; • % Cost RA • Mortality per 1000 inpatients. |

| Tamer, S. et al. (2015) [35] | Antimicrobial stewardship to optimize the use of antimicrobials for surgical prophylaxis in Egypt: a multicentre pilot intervention study. | Egypt | Five tertiary acute care surgical hospitals with infection control programs and ASPs teams. | 1303 patients: 745 patients pre- and 558 post-intervention: ASP. | • 12 months long; • % Correct dose, duration, timing of antibiotics. |

| Tillekeratne, L.G. et al. (2015) [55] | Use of rapid influenza testing to reduce antibiotic prescriptions among outpatients with influenza-like illness in Southern Sri Lanka. | Sri Lanka | Outpatient department in a 1500-bed teaching hospital in Karapitiya with >1000 patients daily. | 10 clinicians and 571 outpatients ≥ 1 year: 316 in phase 1 and 241 in phase 2. Illness: influenza-like illness. | • 20 months long; • % Encounters with antibiotics; • % Appropriate prescription. |

| Intervention Activities | Aiken, AM et al. (2013) [46] | Akter, SF et al. (2009) [31] | Awad, AI et al. (2006) [56] | Bernasconi, A et al. (2018) [30] | Bhuller, HS et al. (2016) [37] | Chalker, J (2001) [59] | Chandy, SJ et al. (2014) [38] | Chowdhury, AK et al. (2007) [32] | Dehn-Lunn, A et al. (2018) [39] | Do, NTT et al. (2016) [60] | Gebretekle, GB et al. (2020) [36] | Gray, AZ et al. (2016) [49] | Hadi, U et al. (2008) [44] | Hamilton, D et al. (2018) [54] | Haque, F et al. (2017) [33] | Hoa, NQ et al. (2017) [61] | Jaggi, N et al. (2012) [40] | Joshi, RD et al. (2019) [51] | Keitel, K et al. (2017) [57] | Korom, RR et al. (2017) [47] | Murni, IK et al. (2015) [45] | Opondo, C et al. (2011) [48] | Petal, S et al. (2016) [41] | Sarma, H et al. (2019) [34] | Shao, AF et al. (2016) [58] | Shrestha, N et al. (2006) [52] | Singh, S et al. (2019) [42] | Siddiqui, S et al. (2007) [53] | Tamer, S et al. (2015) [35] | Tillekeratne, L et al. (2015) [55] | Trap, B et al. (2001) [62] | Wahstrom, R et al. (2003) [50] | Wattal, C et al. (2017) [43] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG origin | Antibiotic Guideline or Policy | D | U | U | A | D | C | D | C | D | A | D | C | D | C | C | A | U | A | A | D | C | A | U | D | A | A | A | D | C | U | U | D | U |

| Organisational | Management Endorsement | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stakeholder Consensus | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Champions | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Institution Incentives | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AMS Programme | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capacity buidling | WORKSHOPS & Seminars | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Follow-up Training | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Academic Detailing | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Focus Group Discussion | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monitoring & review | Audit & Feedback | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antimicrobial Restriction | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reminders | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Practice Supervision & Feedback | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CDSS | Quick Reference | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clinical Algorithms | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rapid Diagnostic Testing Tools | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Persua-Sive Activities | Sharing audit results across depts. | X | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conditional Donation of Equipment and Funds | X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Result | Studies Showing the Intervention Had a Positive Direction of Effect | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adherence to Clinical Guidelines Indicated by Improvement in Domain Areas | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study Design (Risk of Bias) | Reduction in Encounters with an Antibiotic | Antibiotics Prescribed Appropriate: Dose, Timing, Duration | Reduction in Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) Per 100/1000 Bed-Days | Reduction in Rate of Clinical Failure | Clinical Guideline Performance Indicator Scores |

| Keitel, K et al. (2017) [57] | RCT (L) | ▲ | ▲ | |||

| Do, NTT et al. (2016) [60] | RCT (L) | ▲ | ||||

| Shoa, AF et al. (2017) [58] | RCT (L) | ▲ | ▲ | |||

| Hoa, NQ et al. (2017) [61] | CRCT (L) | ▼ | ▲ | |||

| Tillekeratne, L et al. (2015) [55] | PPI (L) | ▲ | ||||

| Wahlstrom, R et al. (2003) [50] | RCT (M) | ▲^ | ||||

| Awad, AI et al. (2006) [56] | CRCT (M) | ▲ | ||||

| Opondo, C et al. (2011) [48] | CRCT (M) | ◄► | ||||

| Gebretekle, GB et al. (2020) [36] | QE (M) | ▲ | ||||

| Sarma, H et al. (2019) [34] | QE (M) | ▲^ | ||||

| Chandy, SJ (2014) [37} | ITS (M) | ◄► | ||||

| Hadi, U et al. (2008) [44] | ITS (M) | ▲^ | ||||

| Wattal, C et al. (2017) [43] | ITS (M) | ◄► | ||||

| Bernasconi, A et al. (2018) [30] | CPPI (M) | ▲ | ▲ | |||

| Haque, F et al. (2017) [33] | CPPI (M) | ▲ | ||||

| Bhuller, HS et al. (2016) [37] | PPI (M) | ▲ | ||||

| Joshi, RD et al. (2019) [51] | PPI (M) | ◄► | ||||

| Murni, IK et al. (2015) [45] | PPI (M) | ▲ | ||||

| Tamar, S et al. (2015) [35] | PPI (M) | ▲ | ▲ | |||

| §Two-tailed Sign Test: †L & M risk of bias | p = 0.0027 | p = 0.1024 | ||||

| Trap, B et al. (2001) [62] | RCT (H) | ◄► | ||||

| Chowdhury, AK et al. (2007) [32] | CRCT (H) | ◄► | ||||

| Shrestha, N et al. (2006) [52] | CRCT (H) | ◄► | ◄► | |||

| Aiken, AM et al. (2013) [46] | ITS (H) | ◄► | ||||

| Chalker, J et al. (2001) [59] | ITS (H) | ▲ | ▲ | |||

| Akter, SF et al. (2009) [31] | CPPI (H) | ▲ | ||||

| Dehn Lunn, A et al. (2018) [39] | PPI (H) | ▲^ | ||||

| Gray AZ et al. (2015) [49] | PPI (H) | ▲ | ||||

| Hamilton, D et al. (2018) [54] | PPI (H) | ◄► | ||||

| Jaggi, N et al. (2012) [40] | PPI (H) | ◄► | ◄► | |||

| Korom, RR et al. (2017) [47] | PPI (H) | ▲ | ||||

| Patel, S et al. (2016) [41] | PPI (H) | |||||

| Siddique, S et al. (2007) [53] | PPI (H) | ▲ | ▲^ | |||

| Singh, S et al. (2019) [42] | PPI (H) | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ||

| §Two-tailed Sign Test: for all studies | p = 0.0005 | p = 0.0066 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Foxlee, N.D.; Townell, N.; Heney, C.; McIver, L.; Lau, C.L. Strategies Used for Implementing and Promoting Adherence to Antibiotic Guidelines in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6030166

Foxlee ND, Townell N, Heney C, McIver L, Lau CL. Strategies Used for Implementing and Promoting Adherence to Antibiotic Guidelines in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2021; 6(3):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6030166

Chicago/Turabian StyleFoxlee, Nicola D., Nicola Townell, Claire Heney, Lachlan McIver, and Colleen L. Lau. 2021. "Strategies Used for Implementing and Promoting Adherence to Antibiotic Guidelines in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 6, no. 3: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6030166

APA StyleFoxlee, N. D., Townell, N., Heney, C., McIver, L., & Lau, C. L. (2021). Strategies Used for Implementing and Promoting Adherence to Antibiotic Guidelines in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 6(3), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6030166