Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis through TOUCH Agents in Selected High TB Burden Wards of Kolkata, India: A Mixed Methods Study on Outcomes and Implementation Challenges

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

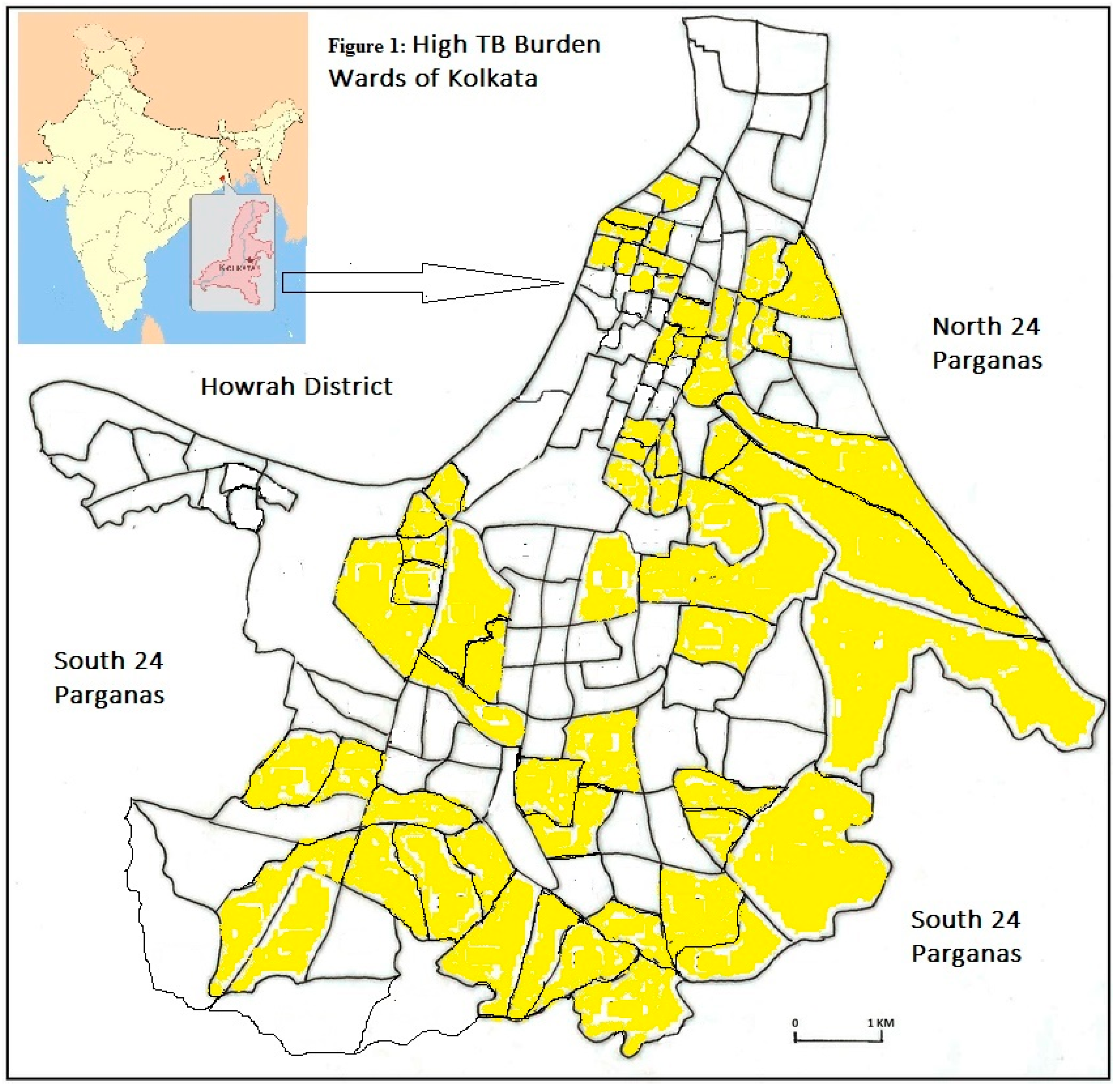

2.2. Study Setting

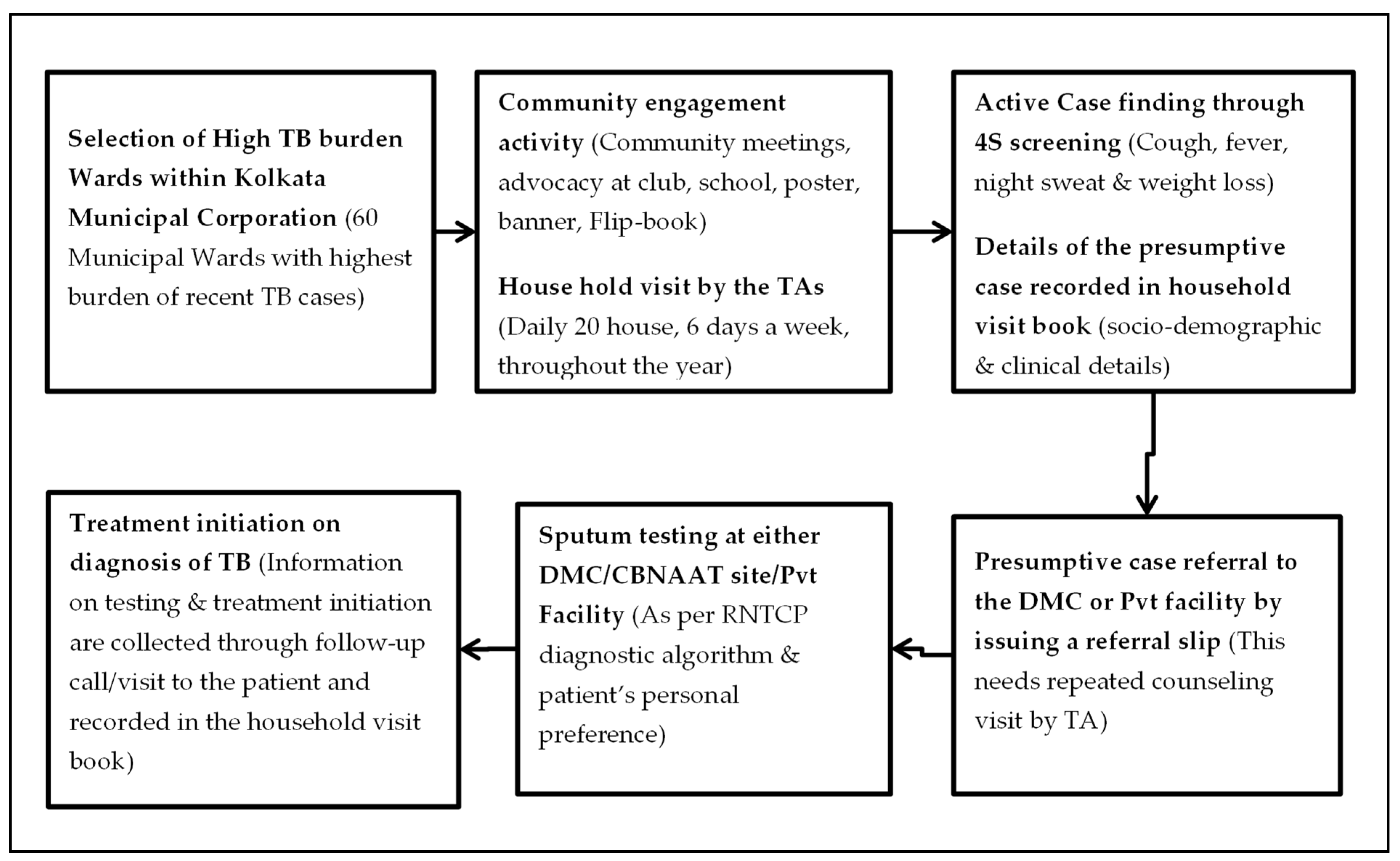

2.2.1. Ward Selection

2.2.2. TOUCH Agent (TA)

2.2.3. Active Case Finding

2.2.4. Recording

2.3. Study Population

2.3.1. Quantitative

2.3.2. Qualitative

2.4. Data Variables, Sources of Data, and Data Collection

2.4.1. Quantitative

2.4.2. Qualitative

2.5. Data Entry and Analysis

2.5.1. Quantitative

2.5.2. Qualitative

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative

3.2. Qualitative

3.2.1. Challenges in House to House Visits and Identification of PTBP:

3.2.2. Challenges in PTBPs Visits to Referred Health Facility for TB Diagnosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2018; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Fox, G.J.; Marais, B.J. Passive case finding for tuberculosis is not enough. Int. J. Mycobact. 2016, 5, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Golub, J.E.; Mohan, C.I.; Comstock, G.W.; Chaisson, R.E. Active case finding of tuberculosis: Historical perspective and future prospects. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2005, 9, 1183–1203. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: http://www.who.int/tb/post2015_TBstrategy.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2018).

- Lönnroth, K.; Tomlin, K.; Afnan-Holmes, H.; Schaap, A.; Golub, J.E.; Shapiro, A.E.; Glynn, J.R.; Kranzer, K.; Corbett, E.L.; Afnan-Holmes, H.; et al. The benefits to communities and individuals of screening for active tuberculosis disease: A systematic review [State of the art series. Case finding/screening. Number 2 in the series]. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2013, 17, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhimbira, F.A.; Cuevas, L.E.; Dacombe, R.; Mkopi, A.; Sinclair, D. Interventions to increase tuberculosis case detection at primary healthcare or community level services. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 11, CD011432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewade, H.D.; Gupta, V.; Satyanarayana, S.; Kharate, A.; Sahai, K.N.N.; Murali, L.; Kamble, S.; Deshpande, M.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, S.; et al. Active case finding among marginalised and vulnerable populations reduces catastrophic costs due to tuberculosis diagnosis. Glob. Health Action 2018, 11, 1494897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewade, H.D.; Gupta, V.; Satyanarayana, S.; Pandey, P.; Bajpai, U.N.; Tripathy, J.P.; Kathirvel, S.; Pandurangan, S.; Mohanty, S.; Ghule, V.H.; et al. Patient characteristics, health seeking and delays among new sputum smear positive TB patients identified through active case finding when compared to passive case finding in India. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, B.M.; Satyanarayana, S.S.; Chadha, A.; Das, B.; Thapa, S.; Mohanty, S.; Pandurangan, E.R.; Babu, J.; Tonsing, K.S.S. Experience of active tuberculosis case finding in nearly 5 million households in India. Pub. Health Act. 2016, 6, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Myint, O.; Saw, S.; Isaakidis, P.; Khogali, M.; Reid, A.; Hoa, N.B.; Kyaw, T.T.; Zaw, K.K.; Khaing, T.M.M.; Aung, S.T. Active case-finding for tuberculosis by mobile teams in Myanmar: Yield and treatment outcomes. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2017, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Central TB Division Directorate General of Health Services. Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme: National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Elimination 2017–2025; Central TB Division Directorate General of Health Services: Delhi, India, 2017.

- USAID U.S. Announces $21 Million in Awards to Address and Treat TB in India|U.S. Embassy & Consulates in India. Available online: https://in.usembassy.gov/u-s-announces-21-million-in-awards-to-address-and-treat-tb-in-india/ (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Abstract Book-47th World Conference on Lung Health of of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Available online: https://thehague.worldlunghealth.org/programme/abstract-book/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Saha, I.; Paul, B. Private sector involvement envisaged in the National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Elimination 2017–2025: Can Tuberculosis Health Action Learning Initiative model act as a road map? Med. J. Armed Forces India 2019, 75, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Website of Kolkata Municipal Corporation. KMC signs MOU with USAID Funded Project THALI. Available online: https://www.kmcgov.in/KMCPortal/outside_jsp/THALI_18_07_2017.jsp (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Nari-O Sishu-Kalyan Kendra Tuberculosis Health Action Learning Initiative (THALI)|www.noskk.in. Available online: http://www.noskk.in/?post_causes=tuberculosis-health-action-learning-initiative-thali (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 1412927927. [Google Scholar]

- Kolkata City Population Census 2011–2019 | West Bengal. Available online: https://www.census2011.co.in/census/city/215-kolkata.html (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Official Web Site of Department of Municipal Affairs, Govt. of West Bengal. Total Number of Slum Pockets, Slum Population Percentage of Slum Population, Total Number of CDS, NHC and NHG Formed in the Urban Local Bodies; Kolkata. Available online: www.wbdma.gov.in/PDF/Total_Number_of_Slum.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Kolkata Municipal Corporation Official Website of Kolkata Municipal Corporation. Available online: https://www.kmcgov.in/KMCPortal/jsp/KMCHealthServiceHome.jsp (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Central TB Division TOG-Chapter 3-Case Finding & Diagnosis Strategy: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Available online: https://tbcindia.gov.in/showfile.php?lid=3216 (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aye, S.; Majumdar, S.S.; Minn Oo, M.; Tripathy, J.P.; Satyanarayana, S.; Thu, N.; Kyaw, T.D.; Wut, K.; Kyaw, Y.; Lynn Oo, N.; et al. Evaluation of a tuberculosis active case finding project in peri-urban areas, Myanmar: 2014–2016. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 70, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorent, N.; Choun, K.; Malhotra, S.; Koeut, P.; Thai, S.; Eam Khun, K.; Colebunders, R.; Lynen, L. Challenges from Tuberculosis Diagnosis to Care in Community-Based Active Case Finding among the Urban Poor in Cambodia: A Mixed-Methods Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshi, D.; Omeje, J.; Oshi, S.; Alobu, I.; Chukwu, N.; Nwokocha, C.; Emelumadu, O.; Ogbudebe, C.; Meka, A.; Ukwaja, K. An evaluation of innovative community-based approaches and systematic tuberculosis screening to improve tuberculosis case detection in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Int. J. Mycobact. 2017, 6, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, B.M.; Satyanarayana, S.; Chadha, S.S. Lessons learnt from active tuberculosis case finding in an urban slum setting of Agra city, India. Indian J. Tuberc. 2016, 63, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamvithayapong-Yanai, J.; Luangjina, S.; Thawthong, S.; Bupachat, S.; Imsangaun, W. Stigma against tuberculosis may hinder non-household contact investigation: A qualitative study in Thailand. Pub. Heal. Act. 2019, 9, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabartty, A.; Basu, P.; Ali, K.M.; Sarkar, A.K.; Ghosh, D. Tuberculosis related stigma and its effect on the delay for sputum examination under the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program in India. Indian J. Tuberc. 2018, 65, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delva, G.J.; Francois, I.; Claassen, C.W.; Dorestan, D.; Bastien, B.; Medina-Moreno, S.; St Fort, D.; Redfield, R.R.; Buchwald, U.K. Active Tuberculosis Case Finding in Port-au-Prince, Haiti: Experiences, Results, and Implications for Tuberculosis Control Programs. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Armstrong-Hough, M.; Turimumahoro, P.; Meyer, A.J.; Ochom, E.; Babirye, D.; Ayakaka, I.; Mark, D.; Ggita, J.; Cattamanchi, A.; Dowdy, D.; et al. Drop-out from the tuberculosis contact investigation cascade in a routine public health setting in urban Uganda: A prospective, multi-center study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in Years | ||

| 0–14 | 36 | (3.2) |

| 15–29 | 206 | (18.2) |

| 30–44 | 323 | (28.5) |

| 45–59 | 280 | (24.7) |

| 60–74 | 184 | (16.3) |

| 75 and above | 32 | (2.8) |

| Not recorded | 71 | (6.3) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 647 | (57.2) |

| Female | 485 | (42.8) |

| Alcohol use * | ||

| Yes | 45 | (3.9) |

| No | 1087 | (96) |

| Tobacco user * | 26 | (2.3) |

| Yes | 175 | (15.5) |

| No | 957 | (84.5) |

| Presenting Symptoms | ||

| Cough with other symptoms | 101 | (8.9) |

| Only cough | 687 | (60.7) |

| No cough but other symptoms | 344 | (30.4) |

| Previous history of TB | ||

| Yes | 84 | (7.4) |

| No | 1048 | (92.6) |

| History of TB of other family # | ||

| Yes | 118 | (10.4) |

| No | 1014 | (89.6) |

| Diabetes | ||

| Yes | 244 | (21.5) |

| No/Unknown $ | 888 | (78.5) |

| HIV | ||

| Yes | 13 | (1.2) |

| No/Unknown $ | 1119 | (98.8) |

| Variable | Total | Not Visiting the Health Facility, n (%) * | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1132 | 419 (37.0) | ||

| Age in Years | ||||

| 0–14 | 36 | 10 (27.8) | 1 | 1 |

| 15–29 | 206 | 63 (30.6) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 1.3 (0.7–2.2) |

| 30–44 | 323 | 117 (36.2) | 1.3 (0.8–2.3) | 1.5 (0.8–2.5) |

| 45–59 | 280 | 93 (33.2) | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) |

| 60–74 | 184 | 64 (34.8) | 1.3 (0.7–2.2) | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) |

| 75 and above | 32 | 4 (12.5) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) |

| Not recorded | 71 | 68 (95.8) | 3.4 (2.0–5.9) | 3.3 (1.9–5.6) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 647 | 211 (32.6) | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 485 | 208 (42.9) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 1.3 (1.2–1.6) |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| Yes | 45 | 28 (62.2) | 1.7 (1.4–2.2) | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) |

| No | 1087 | 391 (36.0) | 1 | 1 |

| Tobacco use | ||||

| Yes | 175 | 74 (42.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| No | 957 | 345 (36.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Presenting Symptom | ||||

| Cough with other symptoms | 101 | 26 (25.7) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) |

| Only cough | 687 | 312 (45.4) | 1.9 (1.6–2.4) | 1.8 (1.5–2.2) |

| No cough but other symptoms | 344 | 81 (23.5) | 1 | 1 |

| Previous history of TB | ||||

| Yes | 84 | 27 (32.1) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 1048 | 392 (37.4) | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) |

| Family history of TB | ||||

| Yes | 118 | 70 (59.3) | 1.7 (1.5–2.0) | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) |

| No | 1014 | 349 (34.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Yes | 244 | 63 (25.8) | 1 | 1 |

| No/Unknown # | 888 | 356 (40.1) | 1.6 (1.2–1.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) |

| HIV | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 1 (7.7) | 1 | 1 |

| No/Unknown # | 1119 | 418 (37.4) | 4.9 (0.7–32.0) | 6.0 (0.9–39.8) |

| Variable | Total | Diagnosed as TB, n (%) * | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 713 | 177 (24.8) | ||

| Age in years | ||||

| 0–14 | 26 | 10 (38.5) | 2.7 (1.5–4.8) | 2.2 (1.2–3.9) |

| 15–29 | 143 | 70 (49.0) | 3.4 (2.3–5.0) | 2.4 (1.6–3.5) |

| 30–44 | 206 | 47 (22.8) | 1.6 (1.0–2.4) | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) |

| 45–59 | 187 | 27 (14.4) | 1 | 1 |

| 60–74 | 120 | 19 (15.8) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) |

| 75 and above | 28 | 3 (10.7) | 0.7 (0.2–2.3) | 0.7 (0.2–1.8) |

| Not recorded | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2.3 (0.4–11.9) | 2.4 (0.4–14.2) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 436 | 95 (21.8) | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 277 | 82 (29.6) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

| Alcohol user | ||||

| Yes | 17 | 4 (23.5) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 696 | 173 (24.9) | 1.1 (0.4–2.5) | 1.3 (0.7–2.5) |

| Tobacco user | ||||

| Yes | 101 | 9 (8.9) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 612 | 168 (27.5) | 3.1 (1.6–5.8) | 2.2 (1.1–4.2) |

| Presenting Symptoms | ||||

| Cough with other symptoms | 75 | 50 (66.7) | 4.4 (3.3–5.8) | 3.3 (2.4–4.4) |

| Only cough | 375 | 57 (15.2) | 1 | 1 |

| No cough but other symptoms | 263 | 70 (26.6) | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | 1.4 (1.1–2.0) |

| Previous history of TB | ||||

| Yes | 57 | 7 (12.3) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 656 | 170 (25.9) | 2.1 (1.0–4.3) | 3.6 (1.7–7.6) |

| Family history of TB | ||||

| Yes | 48 | 29 (60.4) | 2.7 (2.1–3.6) | 2.7 (2.0–3.6) |

| No | 665 | 148 (22.3) | 1 | 1 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Yes | 181 | 54 (29.8) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) |

| No | 532 | 123 (23.1) | 1 | 1 |

| HIV | ||||

| Yes | 12 | 1 (8.3) | 1 | 0.8 (0.1–5.8) |

| No/Unknown | 701 | 176 (25.1) | 3.0 (0.5–19.8) | 1 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dey, A.; Thekkur, P.; Ghosh, A.; Dasgupta, T.; Bandopadhyay, S.; Lahiri, A.; Sanju S V, C.; Dinda, M.K.; Sharma, V.; Dimari, N.; et al. Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis through TOUCH Agents in Selected High TB Burden Wards of Kolkata, India: A Mixed Methods Study on Outcomes and Implementation Challenges. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4040134

Dey A, Thekkur P, Ghosh A, Dasgupta T, Bandopadhyay S, Lahiri A, Sanju S V C, Dinda MK, Sharma V, Dimari N, et al. Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis through TOUCH Agents in Selected High TB Burden Wards of Kolkata, India: A Mixed Methods Study on Outcomes and Implementation Challenges. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2019; 4(4):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4040134

Chicago/Turabian StyleDey, Abhijit, Pruthu Thekkur, Ayan Ghosh, Tanusree Dasgupta, Soumyajyoti Bandopadhyay, Arista Lahiri, Chidananda Sanju S V, Milan K. Dinda, Vivek Sharma, Namita Dimari, and et al. 2019. "Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis through TOUCH Agents in Selected High TB Burden Wards of Kolkata, India: A Mixed Methods Study on Outcomes and Implementation Challenges" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 4, no. 4: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4040134

APA StyleDey, A., Thekkur, P., Ghosh, A., Dasgupta, T., Bandopadhyay, S., Lahiri, A., Sanju S V, C., Dinda, M. K., Sharma, V., Dimari, N., Chatterjee, D., Roy, I., Choudhury, A., Shanmugam, P., Saha, B. K., Ghosh, S., & Nagaraja, S. B. (2019). Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis through TOUCH Agents in Selected High TB Burden Wards of Kolkata, India: A Mixed Methods Study on Outcomes and Implementation Challenges. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 4(4), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4040134