“I-We-I”: Visualizing Adolescents’ Perceptions and Apprehension to Transition to Adult HIV Care at a Supportive Transition Facility in the Cape Town Metropole, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

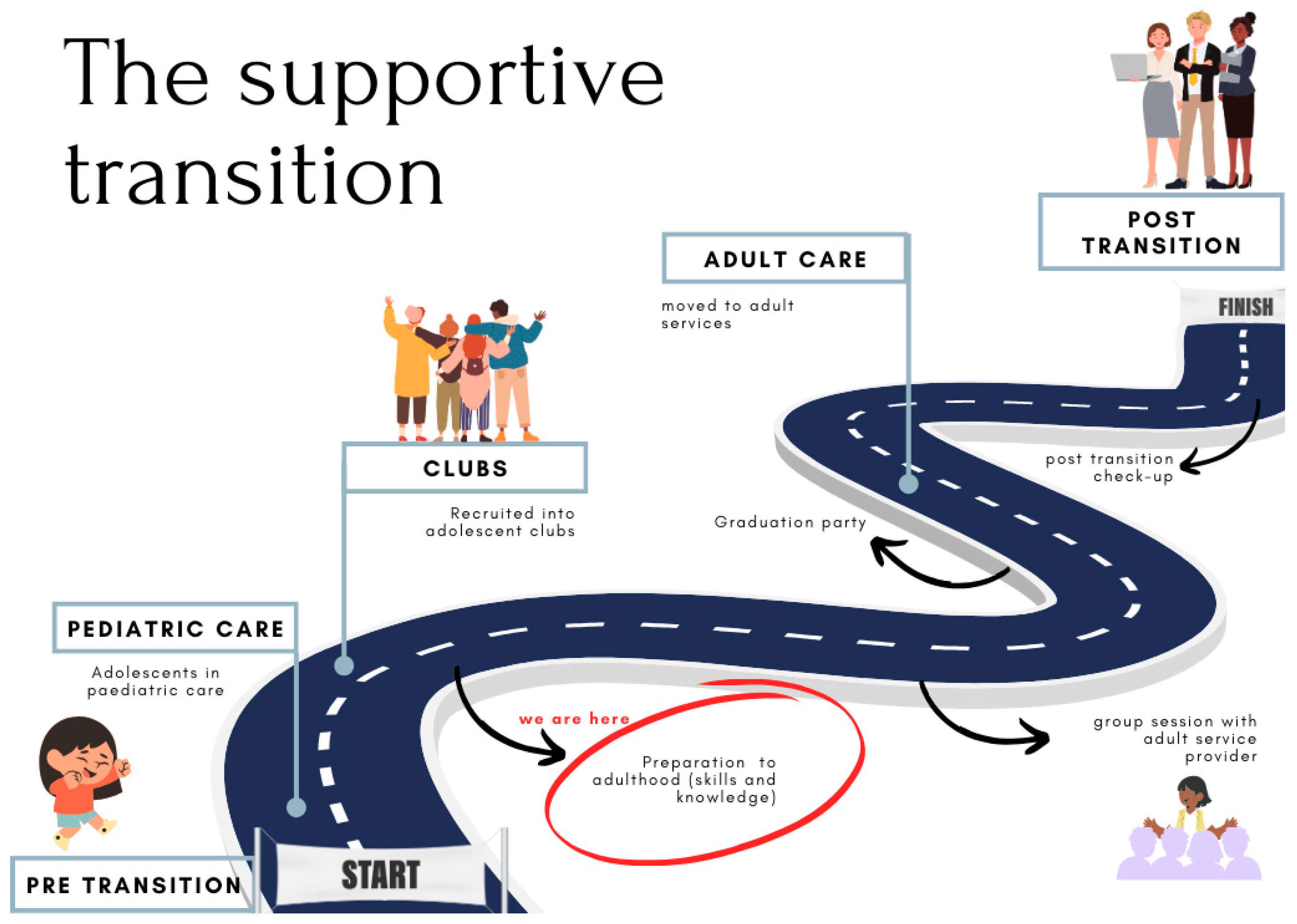

2.2. Study Context

2.3. Sampling and Participants

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Rigour

2.8. Ethics Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Themes

3.2. Theme 1: Not Ready to Transition

3.2.1. Apprehension About Adult Care

So yeah, it made me stand every month outside, cold, around 7. I’ve been standing two hours and another three hours extra inside and another four hours in the pharmacy.(P2, Male, 18 years)

I didn’t like the time management. I didn’t like sitting there. It felt like a hospital you gonna die! Yo, I didn’t like I didn’t like that fact. Like, cause every time you just got sick. And then, it’s like you go to pharmacy, eight hours sitting there, eight hours at pharmacy.(P6, Female, 16)

And there you get hungry. I think in more ways than one because you won’t be getting the connection.(P10, Female, 19)

They will split it. I don’t know how to put it, but they will split it into a thousand [different stories] so that everyone knows that you have [HIV]. That is the thing that I don’t want to talk about because people will spread it all over and it’s going to be a thing.(P2, Male, 18)

I can’t be alone. I can’t return there. You see, I’m going to be alone there.(P16, Female, 16)

It feels like a loss, ma’am, a big loss, ma’am, where you, sometimes when you’re alone, you think about life, you also think about, eish.(P21, Male, 18)

3.2.2. Resistance to Transition

Because while we’re waiting for whoever, you make your hot chocolate and eat your food. They don’t have that there.(P1, Female, 19)

Yeah, it’s not easy, it’s not easy to share.(P4, Male, 19)

And I really love that like being feeling safe here. So, I don’t think we’re yet ready to leave here.(P13, Female, 14)

I don’t feel so exactly prepared. I like to go in situations when they come to me. I’m not a forward-thinking person, so I’m not sure about that. So, to me, that I’m not fully equipped to leave [this facility] and go to a clinic.(P23, Female, 18)

3.3. Theme 2: Self-Management

This picture I look at me, and I say to myself “I don’t look like the person that has HIV”. People can talk and say that I am HIV positive, but no one will see me that I am HIV positive. And I am also happy, and I am not asking myself that I should kill myself because I am HIV positive or what. It’s just that I am happy in life.(P9, Female, 19)

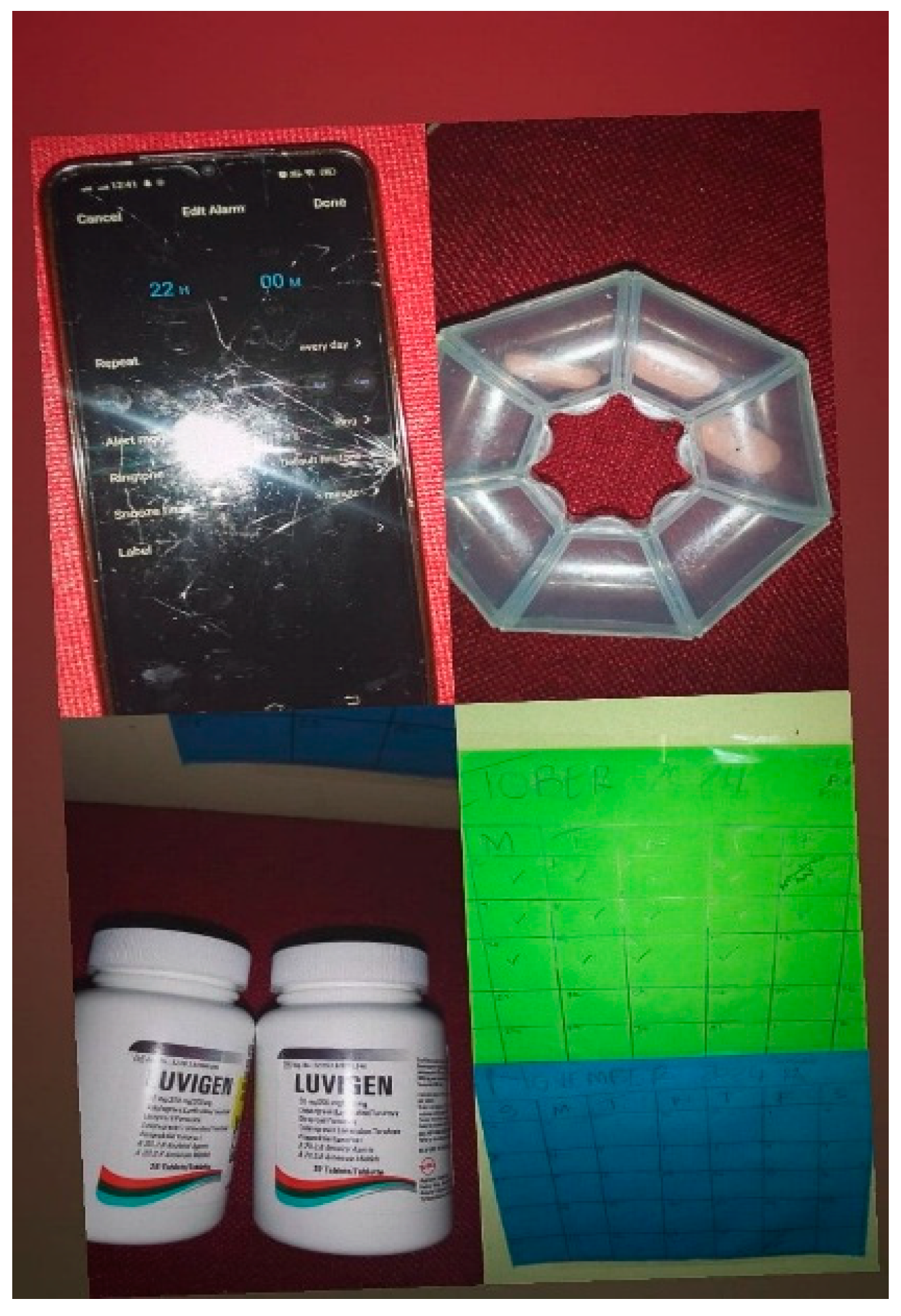

I think of my medication as… my oxygen, part of my life.(P2, Male, 18)

Cause eventually I’m going to be an adult also… So, if I don’t like, try and depend on myself, who will [be there]? If I don’t try to motivate myself, who will motivate me? Because, like, of course, it’s my life.(P23, Female, 18)

I don’t know, um, my escape to, I don’t know, but it is like, this whole picture is an escape to the whole, to the world, because when I write, like, my diary, I just want to be alone.(P1, Female, 19)

3.4. Theme 3: Challenges to Adherence

3.4.1. Physical/Tangible Challenges to Remain Adherent

I always drink my pills from Monday to Friday. The weekend? No, I forget.(P15, Female, 18)

3.4.2. Mental/Emotional Challenges to Remain Adherent

And the reason why I felt like I was all bad is because I have siblings. My siblings don’t have HIV. So, I was like, why me?(P1, Female, 19)

If it wasn’t a bad thing, why would you wake up early in the morning, stay in [the line] 4 hours, then 3 hours [in the pharmacy] extra? And walk miles to… No. It’s not a good thing. It’s a bad thing. Some people die. With just a small mistake.(P2, Male, 18)

3.5. Theme 4: Psychosocial Support

Even at home, there is no one who randomly talks about, like, HIV, like, I don’t live home like, I don’t have a family that—I can’t say acknowledge but something like they are not as supporting because my, my person who I got HIV from, he is no longer.(P12, Female, 19)

Like, see, when this month, oh, it’s close to December and I might be busy, I have to know that I give, like, my cousin my calendars. This is not my room. So, it’s my cousin’s calendar. So that when I take pills, I can tell her that, okay, I’ve taken my pills, then she ticks.(P1, Female, 19)

My father was yelling at me, telling me I’m not taking the tablets. You know what happens now if you don’t take the tablets. It was the wrong medication.(P2, Male, 18)

There must be a limit, yeah.(P3, Male, 18)

And, yeah, I don’t like them to keep reminding me. Because I feel like I have my own strategies that I use.(P4, Male, 19)

3.6. Theme 5: Adolescent-Friendly Services: Filling the Gap

3.6.1. Groups Improve Physical Health

So, yeah, I just appreciate the education, the people, the doctors because they are the ones who put me here. There’s nothing else. Because if it wasn’t for [my doctor], I don’t know what I would have been. Maybe I would have gotten that aids or something.(P15, Female, 18)

I didn’t expect to be where I am, first of all, and I didn’t expect that I would, I would have achieved so many, like, the, I took the picture with the tablets because it is one of the things, okay, pills are one of the things that I suffered, like, to, I was struggling very much to take the pills, so that’s why I took my certificate with the pills because of that, like, if, if, if I didn’t take the pills, I wouldn’t be here, and me taking the pills made me achieve all of those things because it was not easy, like, I mean, like, I was one of the top achievers.(P1, Female, 19)

3.6.2. Groups Improve Psychological Wellbeing

There’s people for you. If your family doesn’t care about you, we care about you. You’re not alone. You’re with people and friends. You will meet friends, and you’ll meet other people also.(P17, Female, 18)

So, every time I feel like, horrible, I write it in my diary, and I feel like it’s the closest thing to me to [this facility].(P1, Female, 19)

3.6.3. Groups Improve Social Wellbeing

So, the first time I met [my doctor], I lost hope. She held my hand, and she told me that we are with you. You’re not alone.(P9, Female, 19)

Like, I wait for the club to come here. Sometimes the sister is busy, so she can’t maybe, like, check WhatsApp, you see. So, I wait until they come. And then we go to the office, and we can talk.(P7, Female, 14)

I ended up knowing other people, getting involved with each other, bonding, and we fell in love with each other.(P3, Male, 18)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. 2023 Global Snapshot on HIV and AIDS Progress and Priorities for Children, Adolescents and Pregnant Women; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Treatment and care in children and adolescents. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hiv/treatment/treatment-and-care-in-children-and-adolescents (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Simbayi, L.; Zuma, K.; Moyo, S.; Marinda, E.; Mabaso, M.; Ramlagan, S.; North, A.; Mohlabane, N.; Dietrich, C.; Naidoo, I. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2017: Towards Achieving the UNAIDS 90-90-90 Targets; HSRC Press: Cape Town, Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni, B.C.; Archary, M.; Subramony, T.; Sibaya, T.; Psaros, C.; Haberer, J.E. ‘It was not okay because you leave your friends behind’: A prospective analysis of transition to adult care for adolescents living with perinatally-acquired HIV in South Africa. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2021, 16, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.; Reda, S.; Martin, S.; Long, P.; Franklin, A.; Bedoya, S.Z.; Wolters, P.L. The Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults with Chronic Illness: Results of a Quality Improvement Survey. Children 2022, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayman, Y.; Crowley, T.; van Wyk, B. Illustrations of Coping and Mental Well-Being of Adolescents Living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa During COVID: A Photovoice Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okegbe, T.; Williams, J.; Plourde, K.F.; Oliver, K.; Ddamulira, B.; Caparrelli, K. Impact of COVID-19 on HIV Adolescent Programming in 16 Countries with USAID-Supported PEPFAR Programs. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2023, 93, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluver, L.; Meinck, F.; Toska, E.; Orkin, F.M.; Hodes, R.; Sherr, L. Multitype violence exposures and adolescent antiretroviral nonadherence in South Africa. AIDS 2018, 32, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurman, T.R.; Luckett, B.; Zani, B.; Nice, J.; Taylor, T.M. Can Support Groups Improve Treatment Adherence and Reduce Sexual Risk Behavior among Young People Living with HIV? Results from a Cohort Study in South Africa. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabizela, S.; van Wyk, B. Viral suppression among adolescents on HIV treatment in the Sedibeng District, Gauteng province. Curationis 2022, 45, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonji, E.F.; Van Wyk, B.; Mukumbang, F.C. Applying the biopsychosocial model to unpack a psychosocial support intervention designed to improve antiretroviral treatment outcomes for adolescents in South Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 41, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchwood, T.D.; Malo, V.; Jones, C.; Metzger, I.W.; Atujuna, M.; Marcus, R.; Bekker, L.G. Healthcare retention and clinical outcomes among adolescents living with HIV after transition from pediatric to adult care: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, B.; Kriel, E.; Mukumbang, F. Retention in care for adolescents who were newly initiated on antiretroviral therapy in the Cape Metropole in South Africa. South. Afr. J. HIV Med. 2020, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanyon, C.; Seeley, J.; Namukwaya, S.; Musiime, V.; Paparini, S.; Nakyambadde, H.; Bernays, S. “Because we all have to grow up”: Supporting adolescents in Uganda to develop core competencies to transition towards managing their HIV more independently. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23w, e25552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladores, S. Concept Analysis of Health Care Transition in Adolescents with Chronic Conditions. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 30, e119–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, L.S.; Kohrt, B.A.; Battles, H.B.; Pao, M. The HIV experience: Youth identified barriers for transitioning from pediatric to adult care. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbebe, S.; Rabie, S.; Coetzee, B.J. Factors influencing the transition from paediatric to adult HIV care in the Western Cape, South Africa: Perspectives of health care providers. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2023, 22, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahourou, D.L.; Gautier-Lafaye, C.; Teasdale, C.A.; Renner, L.; Yotebieng, M.; Desmonde, S.; Leroy, V. Transition from paediatric to adult care of adolescents living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges, youth-friendly models, and outcomes. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, V.; Zaner, S.; Ryscavage, P. HIV healthcare transition outcomes among youth in North America and Europe: A review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanoni, B.C.; Archary, M.; Sibaya, T.; Musinguzi, N.; Haberer, J.E. Transition from pediatric to adult care for adolescents living with HIV in South Africa: A natural experiment and survival analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegede, O.E.; van Wyk, B. Transition Interventions for Adolescents on Antiretroviral Therapy on Transfer from Pediatric to Adult Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chem, E.D.; Ferry, A.; Seeley, J.; Weiss, H.A.; Simms, V. Health-related needs reported by adolescents living with HIV and receiving antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic literature review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 25, e25921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, T.H.; Wallace, M.L.; Snyder, K.L.; Robson, V.K.; Mabud, T.S.; Kalombo, C.D.; Mabud, T.S. South African healthcare provider perspectives on transitioning adolescents into adult HIV care. South Afr. Med. J. 2016, 106, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petinger, C.; Crowley, T.; van Wyk, B. Experiences of adolescents living with HIV on transitioning from pediatric to adult HIV care in low and middle-income countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis Protocol. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petinger, C.; van Wyk, B.; Crowley, T. Mapping the Transition of Adolescents to Adult HIV Care: A Mixed-Methods Perspective from the Cape Town Metropole, South Africa. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukumbang, F.C.; van Wyk, B. Leveraging the Photovoice Methodology for Critical Realist Theorizing. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406920958981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Sciences Research Council. Western Cape Province Has the Lowest HIV Prevalence Rate in South Africa; Human Sciences Research Council: Cape Town, Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Davey, L.; Jenkinson, E. Doing Reflexive Thematic Analysis. In Bager-Charleson Alistair; McBeath, S., Ed.; Supporting Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Colorafi, K.J.; Evans, B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2016, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cope, D.N. Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Methods Mean. 2014, 41, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taukeni, S.G. Biopsychosocial Model of Health. Psychology and Psychiatry: Open access. Res. Gate 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heniff, L.; France, N.F.; Mavhu, W.; Ramadan, M.; Nyamwanza, O.; Willis, N.; Byrne, E. Reported impact of creativity in the Wakakosha (‘You’re Worth It’) internal stigma intervention for young people living with HIV in Harare, Zimbabwe. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavhu, W.; Willis, N.; Mufuka, J.; Bernays, S.; Tshuma, M.; Mangenah, C.; Cowan, F.M. Effect of a differentiated service delivery model on virological failure in adolescents with HIV in Zimbabwe (Zvandiri): A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e264–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanfuka, E.K.; Kafuko, A.; Nakanjako, R.; Ssenfuuma, J.T.; Kaawa-Mafigiri, D. ‘You Are Always Worried and Have No Peace, You Cannot Be a Normal Adolescent’: A Qualitative Study of the Effects of Mental Health Problems on the Social Functioning of Adolescents Living with HIV in Uganda. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2024, 23, 23259582241298166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Papagni, R.; Segala, F.V.; Pellegrino, C.; Panico, G.G.; Frallonardo, L.; Saracino, A. Stigma and mental health among people living with HIV across the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, B.C.; Sibaya, T.; Cairns, C.; Haberer, J.E. Barriers to Retention in Care are Overcome by Adolescent-Friendly Services for Adolescents Living with HIV in South Africa: A Qualitative Analysis. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanoni, B.C.; Archary, M.; Sibaya, T.; Musinguzi, N.; Gethers, C.T.; Goldstein, M.; Haberer, J.E. Acceptability, feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of the mHealth intervention, InTSHA, on retention in care and viral suppression among adolescents with HIV in South Africa: A pilot randomized clinical trial. AIDS Care–Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. AIDS Care 2024, 36, 983–992. [Google Scholar]

- Adhiambo, H.F.; Mwamba, C.; Lewis-Kulzer, J.; Iguna, S.; Ontuga, G.M.; Mangale, D.I.; Kwena, Z.A. Enhancing engagement in HIV care among adolescents and young adults: A focus on phone-based navigation and relationship building to address barriers in HIV care. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0002830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metje, A.; Shaw, S.; Mugo, C.; Awuor, M.; Dollah, A.; Moraa, H.; Njuguna, I. Sustainability of an evidence-based intervention supporting transition to independent care for youth living with HIV in Kenya. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0004111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernays, S.; Tshuma, M.; Willis, N.; Mvududu, K.; Chikeya, A.; Mufuka, J.; Mavhu, W. Scaling up peer-led community-based differentiated support for adolescents living with HIV: Keeping the needs of youth peer supporters in mind to sustain success. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23, e25570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atujuna, M.; Simpson, N.; Ngobeni, M.; Monese, T.; Giovenco, D.; Pike, C.; Bekker, L.G. Khuluma: Using Participatory, Peer-Led and Digital Methods to Deliver Psychosocial Support to Young People Living with HIV in South Africa. Front. Reprod. Health 2021, 3, 687677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonkhai, A.A.; Kuti, K.M.; Hirschhorn, L.R.; Kuhns, L.M.; Garofalo, R.; Johnson, A.K.; Taiwo, B.O. Successful Implementation Strategies in iCARE Nigeria—A Pilot Intervention with Text Message Reminders and Peer Navigation for Youth Living with HIV. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Sub-Category | Total (N = 24) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 13–15 | 8 |

| 16–19 | 16 | |

| Sex | Female | 15 |

| Male | 9 |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Not ready to transition | Apprehension about adult care | Negative experiences at local clinic |

| Reluctance to transition to adult care | ||

| Anticipated loss of peer connection at local clinic | ||

| Experiences of stigma and discrimination | ||

| “We’ll be hungry at the adult clinic” | ||

| Resistance to transition | Improved service at current facility | |

| Difficulty talking in groups | ||

| Not ready to transition | ||

| Self-management | Taking responsibility | Acceptance of living with HIV |

| Healthy living | ||

| Management of mental wellness | ||

| Internal motivation | ||

| Sublimation | ||

| Navigating personal accountability and self-reliance | ||

| “Taking my medication is like oxygen” | ||

| Challenges to adherence | Physical/tangible challenges | Forgetting to breathe; forgetting to take medication |

| Pill fatigue | ||

| Mental/emotional challenges | Negative feelings about self | |

| Negative feelings about HIV | ||

| Psychosocial support | Positive support outside of healthcare | Support from family |

| Multiple sources of support | ||

| Insufficient support outside of healthcare | Overbearing caregivers | |

| Lack of support at home | ||

| Adolescent-friendly services: filling the gap | Groups improve physical health | Increasing HIV knowledge |

| Linking adherence to personal success | ||

| Health care provider helping adherence | ||

| Groups improve psychological wellbeing | Group mitigating isolation | |

| Remembering to breathe/strategies to remain adherent | ||

| Supplement to the facility | ||

| Groups improve social wellbeing | Group mitigating isolation | |

| Remembering to breathe/strategies to remain adherent | ||

| Supplement to the facility |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petinger, C.; van Wyk, B.; Crowley, T. “I-We-I”: Visualizing Adolescents’ Perceptions and Apprehension to Transition to Adult HIV Care at a Supportive Transition Facility in the Cape Town Metropole, South Africa. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10050126

Petinger C, van Wyk B, Crowley T. “I-We-I”: Visualizing Adolescents’ Perceptions and Apprehension to Transition to Adult HIV Care at a Supportive Transition Facility in the Cape Town Metropole, South Africa. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(5):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10050126

Chicago/Turabian StylePetinger, Charné, Brian van Wyk, and Talitha Crowley. 2025. "“I-We-I”: Visualizing Adolescents’ Perceptions and Apprehension to Transition to Adult HIV Care at a Supportive Transition Facility in the Cape Town Metropole, South Africa" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 5: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10050126

APA StylePetinger, C., van Wyk, B., & Crowley, T. (2025). “I-We-I”: Visualizing Adolescents’ Perceptions and Apprehension to Transition to Adult HIV Care at a Supportive Transition Facility in the Cape Town Metropole, South Africa. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(5), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10050126