The Effect of a Life-Stage Based Intervention on Depression in Youth Living with HIV in Kenya and Uganda: Results from the SEARCH-Youth Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context

2.2. Depression Survey—Participants

2.3. Depression Survey—Data Collection

2.4. Depression Survey—Analysis

2.5. Qualitative Study—Participants

2.6. Qualitative Study—Data Collection

2.7. Qualitative Study—Analysis

3. Results

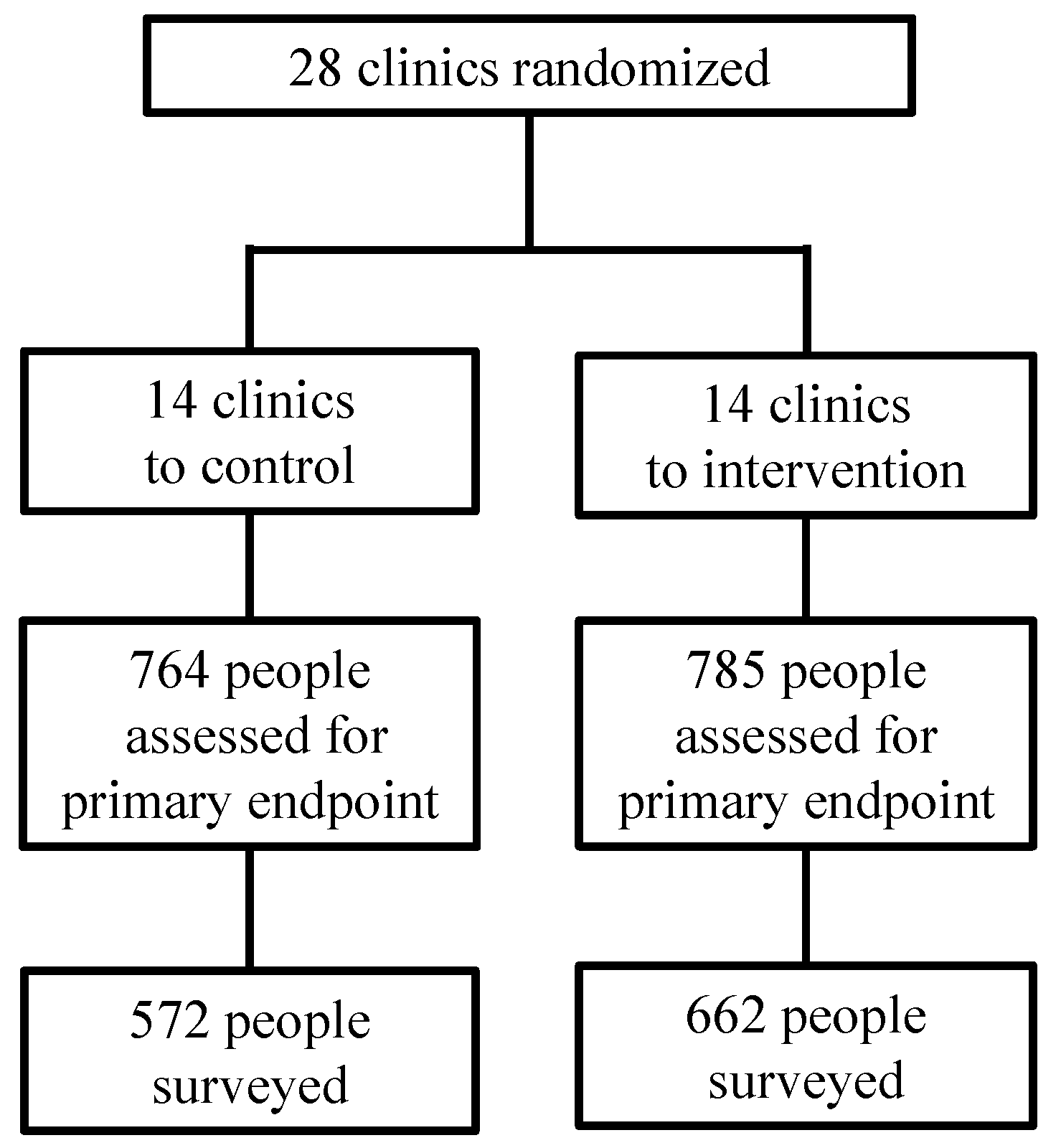

3.1. Participants

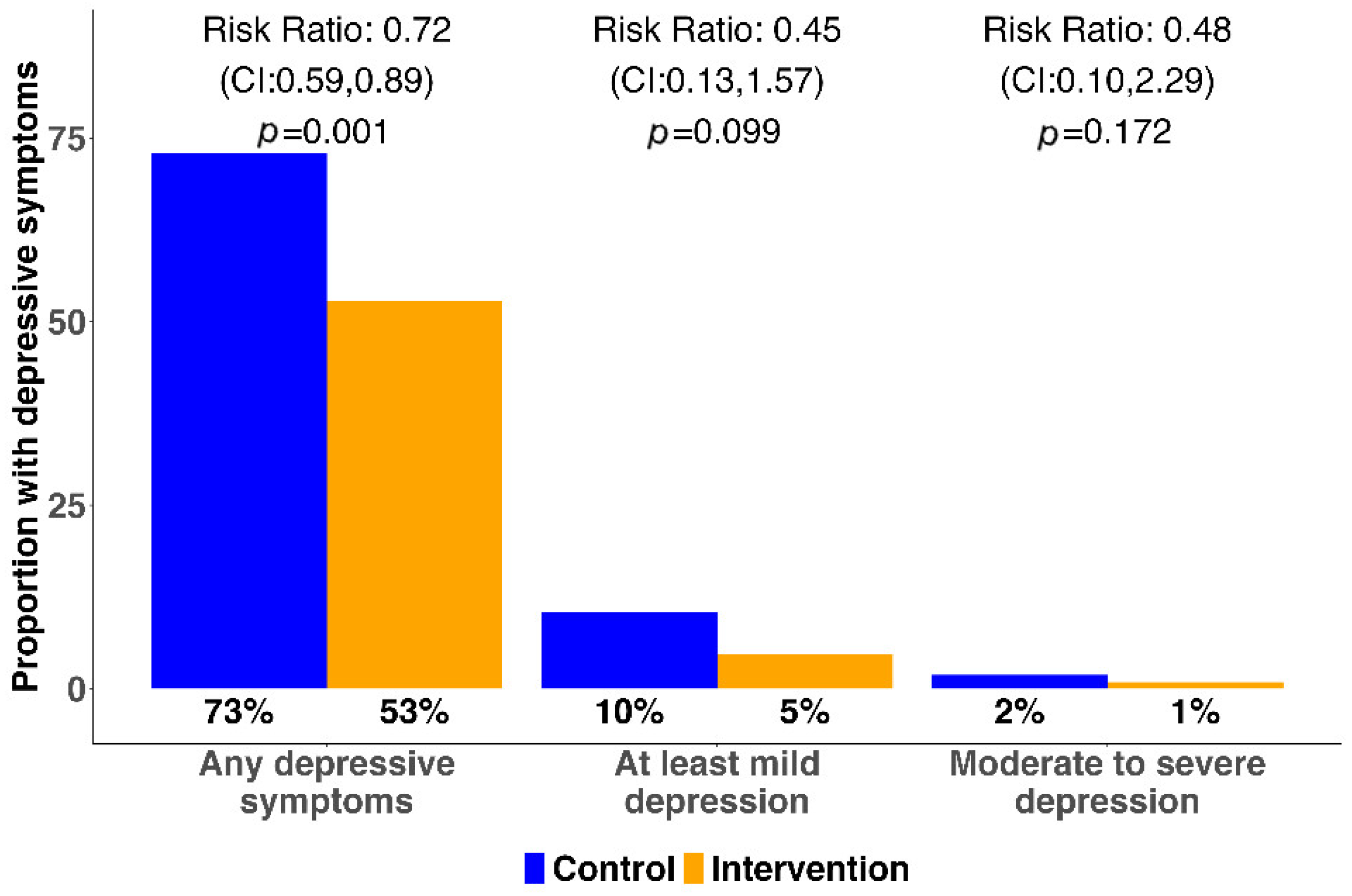

3.1.1. Prevalence of Depression

3.1.2. Prevalence of Recent Major Life Events

3.1.3. Social Pressures, Social Supports, and Substance Use

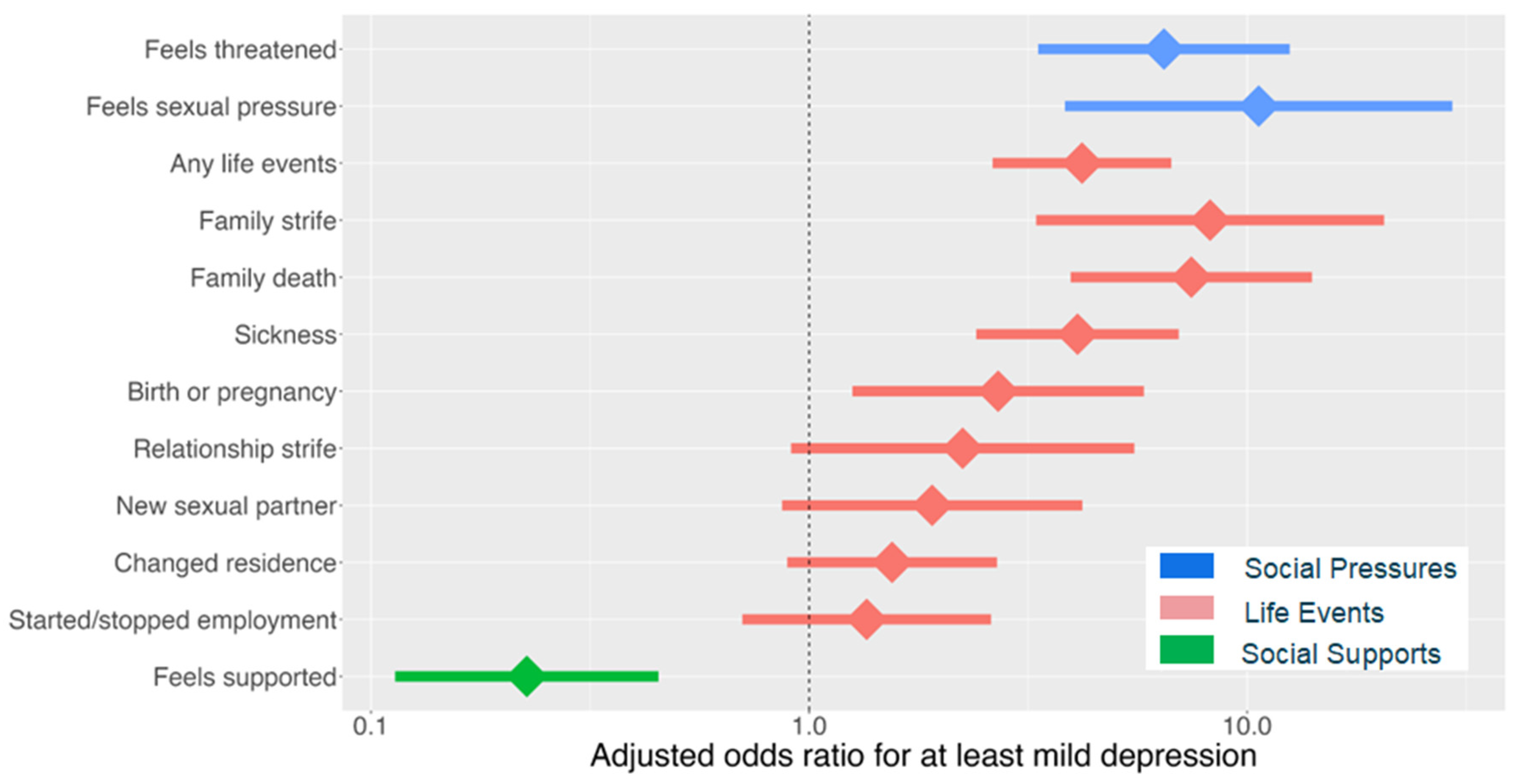

3.1.4. Predictors of at Least Mild Depression

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Depression: Social Etiologies

Suicidal Thoughts

“I had just tested positive, and I never wanted to take HIV drugs, that’s why I wanted to kill myself. What saved me was the people at home who came to my rescue when I was still vomiting, they gave me water and porridge, and I became okay. After some days I was taken to the health facility where counsellors educated me about the goodness of being on HIV medication. That’s when I accepted to start care, and by the way, I was able to regain my energy thereafter”.(Female, 23 y.o., intervention arm, Uganda)

“People always conflict when staying together, and so instead of sitting down and talking about the issue he just takes an overdose of the medication; he always believes that is the only solution. <Later in the interview> I think that is what runs through his mind <that I will leave him> but I told him that leaving would not solve anything and if I were to leave, I would not have come back after I left. The provider is the one who called and convinced me to come back, so we came to the same provider who counselled him, and he promised that he had understood. … [But] it did not even take a month before he took another overdose”.(Spouse of 23 y.o. male, control arm, Kenya)

Loneliness

“I did not feel good at that time, I hated myself inside me. I asked myself, at this age of mine, I am HIV positive, what is my future going to be like? I had so many thoughts. After I started coming here to the clinic, I would meet young people, those who are breast feeding, and those who are older than me. I saw my age-mates; I saw that everyone is affected, and I accepted my situation the way it was. I believed that HIV does not kill, it only kills fools”.(Female, 18 y.o., intervention arm, Uganda)

Self-Hatred

“I have been motivated through pieces of advice and health education from the providers as well as family members. They always try to offer me counselling and advise me because they would not want to lose me. Therefore, I just adhere to my medication for the sake of my family but to me, I hate it. … I do not understand why I was born with the virus. This has been my concern ever since. My younger brother, who passed on, was not infected; yet the first-born is infected, and I do not know why. … The second born and third born are not infected; hence, I cannot understand why it is so”.(Male, 18 y.o., intervention arm, Kenya)

“I was thinking to myself, if people get to learn that I am on ART—I am the last born of five girls—if they get to learn that I am HIV positive, won’t they reject me? But later, it did not matter to me whether they rejected me; I just decided to take my ARVs—you never know what the future holds. … Later on, I realized that most of the people at the HIV clinic were from my village, and I also felt strongly that I was not alone in this situation”. (ARV = antiretroviral medication).(Female, 22 y.o., intervention arm, Uganda)

“The issue I had with S is that he hated himself; he suffered self-rejection, but ‘death’ also rejected him, and his situation was so bad. He was not like a human being, S consumed a lot of alcohol to the extent that sometimes we had to carry him off the road. When he would get home, he would say, ‘If only it was possible, I would take poison and die’. … I was bothered about the fact that he is a young person that hates himself. But now I am happy that at this point in time, he loves himself and his partner as well. I ask God that S stays with his wife”.(Sister of 23 y.o. male, control arm, Uganda)

3.2.2. Self-Acceptance

“It happened that she visited the hospital for her antenatal services and there she [my wife] got tested HIV positive. She immediately called me, and I did not show up but instead invited the nurse to our home a few days later. The nurse visited, and we had very good times together full of counselling. That night after the nurse, we also talked about our own life and how to live and we basically accepted the condition. I assured her that despite not being HIV positive, I am ready to live with her”.(Husband of 20 y.o. female, intervention arm, Kenya)

Importantly, acceptance sometimes preceded enrolment in care; in these cases, the intervention functioned as a support for structures already in place at home. For example, family members mentioned how providers (who were sometimes also relatives) counseled them on how to handle AYAH: “Other days he <my son> would call and tell me he was sick and I told my sister-in-law about it. She told me to handle my son gently and encourage my son to come back so that we could help him. ‘If you handle him harshly, he will feel rejected because of his status.’”(Mother of 24 y.o. male, intervention arm, Kenya)

3.2.3. Life-Stage-Based Assessment, from the Provider’s Perspective

“In the past, if [AYAH] had an issue, they would deal with it personally … Currently, if they come, we start by asking them about their issues before we even open the files. We talk to them about general issues not regarding their medication. I believe that SEARCH Youth brought that aspect and created time for talking about their issues without worrying about reducing the queue. Most of the clients feel that this is the best thing that happened to them. Most of them would call and write messages asking if I am at the clinic. If I tell them I am not around, they will not come because they believe that they need to talk”.(Nurse, intervention arm, Kenya)

“Another thing I have learnt is if a youth does not like you, the health provider, you cannot offer them HIV care at all. …Yes, you must build a rapport. Those youth rarely give their trust to anyone; if they, for instance, have not liked you, they won’t share with you anything, and actually they might not keep you as their provider. It’s better to refer them to someone else they are free with and whom they like”.(Clinical Officer, intervention arm, Uganda)

“For them to trust me, they discovered that I would keep their secrets…. Those already in care always refer their friends to me in case they need any HIV care services, after assuring them that I would confidentially keep their health information”.(Peer Educator 4, intervention arm, Uganda)

“The things that adolescents don’t like and how these can be communicated to them? For example, the adolescent may come, and they have been raped, you ask them, and they cannot give you a response. But when you observe, you notice that the way she is sitting is not right…the sitting posture. How to handle them when they have a challenge, getting them treatment buddies. You link them to a fellow youth and let them know that this one is in the same situation as they are”.(Peer educator 2, intervention arm, Uganda)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Potential Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statements

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Prompt: Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? | ||||

| Not At All | Several Days | More than Half the Days | Nearly Every Day | |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| □ | □ | □ | □ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ |

If an individual scores 1 or more on question 9:

| Yes Yes | No No | ||

If an individual scored 2 or 3 on any 5 symptoms:

| Yes Yes Yes Yes | No No No No | ||

| Life Events | ||||

| Have you visited any other clinic services in the last 3 months? 1: Reproductive health services 2: Mental health services 3: Peer support 4: Facilitated disclosure services 5: Other 99: Did not access other clinic service Do any of the following apply to you? 1: Currently pregnant 2. Gave birth in the last 1 month 3. Suffered pregnancy loss 4. None of the above Any recent major life events in the last 3 months? 1: Start or stop school or employment 2: Change in residence 3: Divorce, separation or relationship strife 4: New sexual partner 5: Family death 6: Sickness 7: Incarceration 8: Family strife 9: Birth or pregnancy -8: Refuse 99: None of the Above | Describe details about major recent life events Do you feel supported by people around you? 1: Yes 0: No [If yes] Who is your support? Does anyone ever hurt or threaten you? 1: Yes 0: No 8: Refuse If yes, who? Parent Partner Other None Do you feel pressured to have sexual activity? Yes No Refuse | |||

| Control (N = 34) | Intervention (N = 79) # | Overall (N = 113) # | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Median [min., max.] | 20.5 [15.0, 24.0] | 21.0 [15.0, 24.0] | 21.0 [15.0, 24.0] |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 18 (52.9%) | 52 (68.4%) | 70 (63.6%) |

| Country | |||

| Kenya | 19 (55.9%) | 45 (59.2%) | 64 (58.2%) |

| Uganda | 15 (44.1%) | 31 (40.8%) | 46 (41.8%) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single, never married | 16 (47.1%) | 29 (38.2%) | 45 (40.9%) |

| Married, monogamous | 14 (41.2%) | 32 (42.1%) | 46 (41.8%) |

| Widowed | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Divorced | 2 (5.9%) | 8 (10.5%) | 10 (9.1%) |

| Married, polygamous | 2 (5.9%) | 5 (6.6%) | 7 (6.4%) |

| Education | |||

| No school | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Primary school | 26 (76.5%) | 55 (72.4%) | 81 (73.6%) |

| Secondary school | 7 (20.6%) | 19 (25.0%) | 26 (23.6%) |

| Tertiary school | 1 (2.9%) | 2 (2.6%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 10 (29.4%) | 26 (34.2%) | 36 (32.7%) |

| In school | 9 (26.5%) | 16 (21.1%) | 25 (22.7%) |

| Unemployed | 15 (44.1%) | 34 (44.7%) | 49 (44.5%) |

| Number of children | |||

| Median [min., max.] | 0 [0, 3.00] | 1.00 [0, 3.00] | 0 [0, 3.00] |

| Baseline care status | |||

| New to care ^ | 19 (55.9%) | 39 (51.3%) | 58 (52.7%) |

| Engaged in care * | 13 (38.2%) | 29 (38.2%) | 42 (38.2%) |

| Re-engaging in care # | 2 (5.9%) | 8 (10.5%) | 10 (9.1%) |

| Control | Intervention | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 572) | (N = 662) | (N = 1234) | |

| Total PHQ-9 score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.11 (2.33) | 1.16 (1.73) | 1.60 (2.08) |

| Median [min., max.] | 1.00 [0, 15.0] | 1.00 [0, 11.0] | 1.00 [0, 15.0] |

| Score >= 1 | |||

| Score = 0 | 154 (26.9%) | 313 (47.3%) | 467 (37.8%) |

| Score >= 1 | 418 (73.1%) | 349 (52.7%) | 767 (62.2%) |

| Score >= 5 | |||

| Score < 5 | 512 (89.5%) | 631 (95.3%) | 1143 (92.6%) |

| Score >= 5 | 60 (10.5%) | 31 (4.7%) | 91 (7.4%) |

| Score >= 10 | |||

| Score < 10 | 561 (98.1%) | 656 (99.1%) | 1217 (98.6%) |

| Score >= 10 | 11 (1.9%) | 6 (0.9%) | 17 (1.4%) |

| PHQ-1: Little interest or pleasure in doing things | |||

| Not at all | 442 (77.3%) | 601 (90.8%) | 1043 (84.5%) |

| Several days | 113 (19.8%) | 55 (8.3%) | 168 (13.6%) |

| More than half the days | 12 (2.1%) | 5 (0.8%) | 17 (1.4%) |

| Nearly every day | 5 (0.9%) | 1 (0.2%) | 6 (0.5%) |

| PHQ-2: Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | |||

| Not at all | 425 (74.3%) | 596 (90.0%) | 1021 (82.7%) |

| Several days | 129 (22.6%) | 54 (8.2%) | 183 (14.8%) |

| More than half the days | 15 (2.6%) | 11 (1.7%) | 26 (2.1%) |

| Nearly every day | 3 (0.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.3%) |

| PHQ-3: Trouble falling/staying asleep, sleeping too much | |||

| Not at all | 385 (67.3%) | 552 (83.4%) | 937 (75.9%) |

| Several days | 164 (28.7%) | 98 (14.8%) | 262 (21.2%) |

| More than half the days | 19 (3.3%) | 12 (1.8%) | 31 (2.5%) |

| Nearly every day | 4 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (0.3%) |

| PHQ-4: Feeling tired or having little energy | |||

| Not at all | 361 (63.1%) | 485 (73.3%) | 846 (68.6%) |

| Several days | 181 (31.6%) | 153 (23.1%) | 334 (27.1%) |

| More than half the days | 27 (4.7%) | 21 (3.2%) | 48 (3.9%) |

| Nearly every day | 3 (0.5%) | 3 (0.5%) | 6 (0.5%) |

| PHQ-5: Poor appetite or overeating | |||

| Not at all | 410 (71.7%) | 519 (78.4%) | 929 (75.3%) |

| Several days | 142 (24.8%) | 126 (19.0%) | 268 (21.7%) |

| More than half the days | 17 (3.0%) | 10 (1.5%) | 27 (2.2%) |

| Nearly every day | 3 (0.5%) | 7 (1.1%) | 10 (0.8%) |

| PHQ-6: Feeling bad about yourself | |||

| Not at all | 494 (86.4%) | 614 (92.7%) | 1108 (89.8%) |

| Several days | 70 (12.2%) | 44 (6.6%) | 114 (9.2%) |

| More than half the days | 6 (1.0%) | 4 (0.6%) | 10 (0.8%) |

| Nearly every day | 2 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| PHQ-7: Trouble concentrating on things | |||

| Not at all | 496 (86.7%) | 622 (94.0%) | 1118 (90.6%) |

| Several days | 66 (11.5%) | 38 (5.7%) | 104 (8.4%) |

| More than half the days | 9 (1.6%) | 2 (0.3%) | 11 (0.9%) |

| Nearly every day | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| PHQ-8: Moving or speaking slowly | |||

| Not at all | 530 (92.7%) | 641 (96.8%) | 1171 (94.9%) |

| Several days | 38 (6.6%) | 19 (2.9%) | 57 (4.6%) |

| More than half the days | 3 (0.5%) | 2 (0.3%) | 5 (0.4%) |

| Nearly every day | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| PHQ-9: Thoughts that you would be better off dead | |||

| Not at all | 555 (97.0%) | 652 (98.5%) | 1207 (97.8%) |

| Several days | 11 (1.9%) | 7 (1.1%) | 18 (1.5%) |

| More than half the days | 6 (1.0%) | 2 (0.3%) | 8 (0.6%) |

| Nearly every day | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| ProgramName | Description |

| YAPS | Young Adolescent Peer Support (YAPS), a youth peer support program |

| PATA | Pediatric and adolescent Treatment Africa, which supports children and adolescents to start and remain on ART |

| NAYA | Provides psychosocial support to increase resilience among young people with HIV in Kenya |

| Blue Cross | An alcohol and substance abuse and mental health support program |

| Ariel Club | A program of the Elizabeth Glazer foundation (EGPAF) targeting children and adolescents up to 19 years old with group psychosocial support at a health facility |

| TASO | The AIDS Support Organization, which places trained counsellors in public health facilities for adherence support |

| TPO | Transcultural Psychosocial Organization, which targets the mental health of youth with viral non-suppression in Uganda, offering home visits and food |

| Mwendo | Supports orphans and vulnerable children with physical and psychosocial needs |

References

- Dessauvagie, A.S.; Jorns-Presentati, A.; Napp, A.K.; Stein, D.J.; Jonker, D.; Breet, E.; Charles, W.; Swart, R.L.; Lahti, M.; Suliman, S.; et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in sub-Saharan adolescents living with HIV: A systematic review. Glob. Ment. Health 2020, 7, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayano, G.; Demelash, S.; Abraha, M.; Tsegay, L. The prevalence of depression among adolescent with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Res. Ther. 2021, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AIDS Info: Global Data on HIV Epidemiology and Response. Available online: https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Vreeman, R.C.; McCoy, B.M.; Lee, S. Mental health challenges among adolescents living with HIV. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20 (Suppl. S3), 21497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Marotta, C.; Saracino, A.; Occa, E.; Putoto, G. Mental health needs of adolescents with HIV in Africa. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A.D.; Lienhard, R.; Didden, C.; Cornell, M.; Folb, N.; Boshomane, T.M.G.; Salazar-Vizcaya, L.; Ruffieux, Y.; Nyakato, P.; Wettstein, A.E.; et al. Mental Health, ART Adherence, and Viral Suppression Among Adolescents and Adults Living with HIV in South Africa: A Cohort Study. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashaba, S.; Cooper-Vince, C.; Maling, S.; Rukundo, G.Z.; Akena, D.; Tsai, A.C. Internalized HIV stigma, bullying, major depressive disorder, and high-risk suicidality among HIV-positive adolescents in rural Uganda. Glob. Ment. Health 2018, 5, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinyanda, E.; Salisbury, T.T.; Levin, J.; Nakasujja, N.; Mpango, R.S.; Abbo, C.; Seedat, S.; Araya, R.; Musisi, S.; Gadow, K.D.; et al. Rates, types and co-occurrence of emotional and behavioural disorders among perinatally HIV-infected youth in Uganda: The CHAKA study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau, J.W.; Kuria, W.; Mathai, M.; Atwoli, L.; Kangethe, R. Psychiatric morbidity among HIV-infected children and adolescents in a resource-poor Kenyan urban community. AIDS Care 2012, 24, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaitho, D.; Kumar, M.; Wamalwa, D.; Wambua, G.N.; Nduati, R. Understanding mental health difficulties and associated psychosocial outcomes in adolescents in the HIV clinic at Kenyatta National Hospital, Kenya. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2018, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemigisha, E.; Zanoni, B.; Bruce, K.; Menjivar, R.; Kadengye, D.; Atwine, D.; Rukundo, G.Z. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in South Western Uganda. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluver, L.D.; Zhou, S.; Orkin, M.; Rudgard, W.; Meinck, F.; Langwenya, N.; Vicari, M.; Edun, O.; Sherr, L.; Toska, E. Impacts of intimate partner violence and sexual abuse on antiretroviral adherence among adolescents living with HIV in South Africa. AIDS 2023, 37, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtge, J.; Theron, L.; van Rensburg, A.; Cowden, R.G.; Govender, K.; Ungar, M. Investigating the Interrelations Between Systems of Support in 13- to 18-Year-Old Adolescents: A Network Analysis of Resilience Promoting Systems in a High and Middle-Income Country. Child Dev. 2021, 92, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Too, E.K.; Abubakar, A.; Nasambu, C.; Koot, H.M.; Cuijpers, P.; Newton, C.R.; Nyongesa, M.K. Prevalence and factors associated with common mental disorders in young people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24 (Suppl. S2), e25705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugo, C.; Kohler, P.; Kumar, M.; Badia, J.; Kibugi, J.; Wamalwa, D.C.; Kapogiannis, B.; Agot, K.; John-Stewart, G.C. Effect of HIV stigma on depressive symptoms, treatment adherence, and viral suppression among youth with HIV. AIDS 2023, 37, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wonde, M.; Mulat, H.; Birhanu, A.; Biru, A.; Kassew, T.; Shumet, S. The magnitude of suicidal ideation, attempts and associated factors of HIV positive youth attending ART follow ups at St. Paul’s hospital Millennium Medical College and St. Peter’s specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filiatreau, L.M.; Pettifor, A.; Edwards, J.K.; Masilela, N.; Twine, R.; Xavier Gomez-Olive, F.; Haberland, N.; Kabudula, C.W.; Lippman, S.A.; Kahn, K. Associations Between Key Psychosocial Stressors and Viral Suppression and Retention in Care Among Youth with HIV in Rural South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 2358–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, M.; Adams, H.R.; Mwanza-Kabaghe, S.; Mbewe, E.G.; Kabundula, P.P.; Mweemba, M.; Birbeck, G.L.; Bearden, D.R. Evaluating the Relationship Between Depression and Cognitive Function Among Children and Adolescents with HIV in Zambia. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 2669–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.T.; Birgegard, G.; Strivens, J.; Hollegien, W.W.G.; van Hattem, N.; Saris, M.T.; Wondergem, M.J.; Toh, C.H.; Almeida, A.M. The European Hematology Exam: The Next Step toward the Harmonization of Hematology Training in Europe. Hemasphere 2019, 3, e291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remien, R.H.; Stirratt, M.J.; Nguyen, N.; Robbins, R.N.; Pala, A.N.; Mellins, C.A. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: The need for an integrated response. AIDS 2019, 33, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurenzi, C.A.; Toit, S.; Ameyan, W.; Melendez-Torres, G.; Kara, T.; Brand, A.; Chideya, Y.; Abrahams, N.; Bradshaw, M.; Page, D.T.; et al. Psychosocial interventions for improving engagement in care and health and behavioural outcomes for adolescents and young people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24, e25741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhana, A.; Abas, M.A.; Kelly, J.; van Pinxteren, M.; Mudekunye, L.A.; Pantelic, M. Mental health interventions for adolescents living with HIV or affected by HIV in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavazos-Rehg, P.; Byansi, W.; Xu, C.; Nabunya, P.; Sensoy Bahar, O.; Borodovsky, J.; Kasson, E.; Anako, N.; Mellins, C.; Damulira, C.; et al. The Impact of a Family-Based Economic Intervention on the Mental Health of HIV-Infected Adolescents in Uganda: Results From Suubi + Adherence. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthiyane, N.; Rapulana, A.M.; Harling, G.; Copas, A.; Shahmanesh, M. Effect of multi-level interventions on mental health outcomes among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dow, D.E.; Mmbaga, B.T.; Gallis, J.A.; Turner, E.L.; Gandhi, M.; Cunningham, C.K.; O’Donnell, K.E. A group-based mental health intervention for young people living with HIV in Tanzania: Results of a pilot individually randomized group treatment trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, N.; Napei, T.; Armstrong, A.; Jackson, H.; Apollo, T.; Mushavi, A.; Ncube, G.; Cowan, F.M. Zvandiri-Bringing a Differentiated Service Delivery Program to Scale for Children, Adolescents, and Young People in Zimbabwe. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2018, 78 (Suppl. S2), S115–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavhu, W.; Willis, N.; Mufuka, J.; Bernays, S.; Tshuma, M.; Mangenah, C.; Maheswaran, H.; Mangezi, W.; Apollo, T.; Araya, R.; et al. Effect of a differentiated service delivery model on virological failure in adolescents with HIV in Zimbabwe (Zvandiri): A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e264–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, V.; Weiss, H.A.; Chinoda, S.; Mutsinze, A.; Bernays, S.; Verhey, R.; Wogrin, C.; Apollo, T.; Mugurungi, O.; Sithole, D.; et al. Peer-led counselling with problem discussion therapy for adolescents living with HIV in Zimbabwe: A cluster-randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, T.; Mwangwa, F.; Balzer, L.B.; Ayieko, J.; Nyabuti, M.; Mugoma, W.E.; Kabami, J.; Kamugisha, B.; Black, D.; Nzarubara, B.; et al. A multilevel health system intervention for virological suppression in adolescents and young adults living with HIV in rural Kenya and Uganda (SEARCH-Youth): A cluster randomised trial. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e518–e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tele, A.K.; Carvajal-Velez, L.; Nyongesa, V.; Ahs, J.W.; Mwaniga, S.; Kathono, J.; Yator, O.; Njuguna, S.; Kanyanya, I.; Amin, N.; et al. Validation of the English and Swahili Adaptation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for Use Among Adolescents in Kenya. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, S61–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, T.L.; Kleinman, A.; Weisz, J.R. Complementing standard western measures of depression with locally co-developed instruments: A cross-cultural study on the experience of depression among the Luo in Kenya. Transcult. Psychiatry 2021, 58, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.P.; Espinosa da Silva, C.; Ziegel, L.; Mugamba, S.; Kyasanku, E.; Malyabe, R.B.; Wagman, J.A.; Mia Ekstrom, A.; Nalugoda, F.; Kigozi, G.; et al. Construct validity and internal consistency of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression screening measure translated into two Ugandan languages. Psychiatry Res. Commun. 2021, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaggwa, M.M.; Namatanzi, B.; Kule, M.; Nkola, R.; Najjuka, S.M.; Al Mamun, F.; Hosen, I.; Mamun, M.A.; Ashaba, S. Depression in Ugandan Rural Women Involved in a Money Saving Group: The Role of Spouse’s Unemployment, Extramarital Relationship, and Substance Use. Int. J. Women’s Health 2021, 13, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaggwa, M.M.; Najjuka, S.M.; Ashaba, S.; Mamun, M.A. Psychometrics of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in Uganda: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 781095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzer, L.B.; van der Laan, M.; Ayieko, J.; Kamya, M.; Chamie, G.; Schwab, J.; Havlir, D.V.; Petersen, M.L. Two-Stage TMLE to reduce bias and improve efficiency in cluster randomized trials. Biostatistics 2023, 24, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangwa, F.; Peng, J.; Balzer, L.B.; Ayieko, J.; Litunya, J.; Johnson-Peretz, J.; Black, D.; Nakigudde, J.; Bukusi, E.; Kamya, M.R.; et al. Impact of the SEARCH-Youth intervention on symptoms of depression in Kenyan and Ugandan youth with HIV in a randomized trial. In Proceedings of the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Denver, CO, USA, 3–6 March 2024; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Lowe, B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhana, A.; Kreniske, P.; Pather, A.; Abas, M.A.; Mellins, C.A. Interventions to address the mental health of adolescents and young adults living with or affected by HIV: State of the evidence. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24 (Suppl. S2), e25713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenzi, C.A.; Gordon, S.; Abrahams, N.; du Toit, S.; Bradshaw, M.; Brand, A.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Tomlinson, M.; Ross, D.A.; Servili, C.; et al. Psychosocial interventions targeting mental health in pregnant adolescents and adolescent parents: A systematic review. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangwa, F.; Charlebois, E.D.; Ayieko, J.; Olio, W.; Black, D.; Peng, J.; Kwarisiima, D.; Kabami, J.; Balzer, L.B.; Petersen, M.L.; et al. Two or more significant life-events in 6-months are associated with lower rates of HIV treatment and virologic suppression among youth with HIV in Uganda and Kenya. AIDS Care 2023, 35, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonji, E.F.; Mukumbang, F.C.; Orth, Z.; Vickerman-Delport, S.A.; Van Wyk, B. Psychosocial support interventions for improved adherence and retention in ART care for young people living with HIV (10–24 years): A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, M.; Bowers, T.; Manda, E.; Cooper, S.; Machando, D.; Verhey, R.; Lamech, N.; Araya, R.; Chibanda, D. ‘Opening up the mind’: Problem-solving therapy delivered by female lay health workers to improve access to evidence-based care for depression and other common mental disorders through the Friendship Bench Project in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2016, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibanda, D.; Weiss, H.A.; Verhey, R.; Simms, V.; Munjoma, R.; Rusakaniko, S.; Chingono, A.; Munetsi, E.; Bere, T.; Manda, E.; et al. Effect of a Primary Care-Based Psychological Intervention on Symptoms of Common Mental Disorders in Zimbabwe: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 316, 2618–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazos-Rehg, P.; Xu, C.; Kasson, E.; Byansi, W.; Bahar, O.S.; Ssewamala, F.M. Social and Economic Equity and Family Cohesion as Potential Protective Factors from Depression Among Adolescents Living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 2546–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okawa, S.; Mwanza Kabaghe, S.; Mwiya, M.; Kikuchi, K.; Jimba, M.; Kankasa, C.; Ishikawa, N. Psychological well-being and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adolescents living with HIV in Zambia. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okinyi, H.M.; Wachira, C.M.; Wilson, K.S.; Nduati, M.N.; Onyango, A.D.; Mburu, C.W.; Inwani, I.W.; Owens, T.L.; Bukusi, D.E.; John-Stewart, G.C.; et al. “I have actually not lost any adolescent since i started engaging them one on one:” training satisfaction and subsequent practice among health providers participating in a standardized patient actor training to improve adolescent engagement in HIV care. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care (JIAPAC) 2022, 21, 23259582221075133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grose, R.G.; Roof, K.A.; Semenza, D.C.; Leroux, X.; Yount, K.M. Mental health, empowerment, and violence against young women in lower-income countries: A review of reviews. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 46, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinck, F.; Cluver, L.D.; Boyes, M.E.; Mhlongo, E.L. Risk and protective factors for physical and sexual abuse of children and adolescents in Africa: A review and implications for practice. Trauma Violence Abus. 2015, 16, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwale, M.; Muula, A.S. Systematic review: A review of adolescent behavior change interventions [BCI] and their effectiveness in HIV and AIDS prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pajares, F. Current directions in self-efficacy research. In Advances in Motivation and Achievement; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1997; Volume 10, pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Eggum-Wilkens, N.D.; Zhang, L.; An, D. An exploratory study of Eastern Ugandan adolescents’ descriptions of social withdrawal. J. Adolesc. 2018, 67, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, I.; Bhana, A.; Myeza, N.; Alicea, S.; John, S.; Holst, H.; McKay, M.; Mellins, C. Psychosocial challenges and protective influences for socio-emotional coping of HIV+ adolescents in South Africa: A qualitative investigation. AIDS Care 2010, 22, 970–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dow, D.E.; Turner, E.L.; Shayo, A.M.; Mmbaga, B.; Cunningham, C.K.; O’Donnell, K. Evaluating mental health difficulties and associated outcomes among HIV-positive adolescents in Tanzania. AIDS Care 2016, 28, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sougou, N.M.; Diedhiou, A.; Diallo, A.I.; Diongue, F.B.; Ndiaye, I.; Ba, M.F.; Ndiaye, S.; Mbaye, S.M.; Samb, O.M.; Faye, A. Analysis of care for adolescent victims of gender-based violence in Senegal: A qualitative study. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2024, 28, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhaye, M.S.; Mkhize, S.M.; Sibanyoni, E.K. Female students as victims of sexual abuse at institutions of higher learning: Insights from Kwazulu-natal, South Africa. SN Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahourou, D.L.; Gautier-Lafaye, C.; Teasdale, C.A.; Renner, L.; Yotebieng, M.; Desmonde, S.; Ayaya, S.; Davies, M.A.; Leroy, V. Transition from paediatric to adult care of adolescents living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges, youth-friendly models, and outcomes. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20 (Suppl. S3), 21528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Depression Survey | Qualitative Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 572) | Intervention (N = 662) | Overall (N = 1234) | Overall (N = 113 #) | |

| Age | ||||

| Median [min., max.] | 21.0 [15.0, 24.0] | 21.0 [15.0, 24.0] | 21.0 [15.0, 24.0] | 21.0 [15.0, 24.0] |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 451 (78.8%) | 539 (81.4%) | 990 (80.2%) | 70 (63.6%) |

| Country | ||||

| Kenya | 258 (45.1%) | 313 (47.3%) | 571 (46.3%) | 64 (58.2%) |

| Uganda | 314 (54.9%) | 349 (52.7%) | 663 (53.7%) | 46 (41.8%) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 230 (40.2%) | 297 (44.9%) | 527 (42.7%) | 45 (40.9%) |

| Married, monogamous | 239 (41.8%) | 258 (39.0%) | 497 (40.3%) | 46 (41.8%) |

| Widowed | 4 (0.7%) | 4 (0.6%) | 8 (0.6%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Divorced | 59 (10.3%) | 67 (10.1%) | 126 (10.2%) | 10 (9.1%) |

| Married, polygamous | 40 (7.0%) | 36 (5.4%) | 76 (6.2%) | 7 (6.4%) |

| Education | ||||

| No school | 22 (3.8%) | 25 (3.8%) | 47 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Primary school | 376 (65.7%) | 420 (63.4%) | 796 (64.5%) | 81 (73.6%) |

| Secondary school | 139 (24.3%) | 172 (26.0%) | 311 (25.2%) | 26 (23.6%) |

| Tertiary school | 35 (6.1%) | 45 (6.8%) | 80 (6.5%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 227 (39.7%) | 221 (33.4%) | 448 (36.3%) | 36 (32.7%) |

| In school | 127 (22.2%) | 155 (23.4%) | 282 (22.9%) | 25 (22.7%) |

| Unemployed | 218 (38.1%) | 286 (43.2%) | 504 (40.8%) | 49 (44.5%) |

| Baseline care status | ||||

| New to care ^ | 136 (23.8%) | 188 (28.4%) | 324 (26.3%) | 58 (52.7%) |

| Engaged in care * | 425 (74.3%) | 444 (67.1%) | 869 (70.4%) | 42 (38.2%) |

| Re-engaging in care ## | 11 (1.9%) | 30 (4.5%) | 41 (3.3%) | 10 (9.1%) |

| Control | Intervention | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 572) | (N = 662) | (N = 1234) | |

| Major life events: | |||

| Had events in prior 3 months | 232 (40.6%) | 219 (33.1%) | 451 (36.5%) |

| Changed residence | 99 (17.3%) | 72 (10.9%) | 171 (13.9%) |

| Changed employment | 62 (10.8%) | 62 (9.4%) | 124 (10.0%) |

| Sickness | 61 (10.7%) | 44 (6.6%) | 105 (8.5%) |

| New partner | 34 (5.9%) | 26 (3.9%) | 60 (4.9%) |

| Birth in last month or pregnant | 24 (4.2%) | 27 (4.1%) | 51 (4.1%) |

| Family death | 23 (4.0%) | 27 (4.1%) | 50 (4.1%) |

| Family strife | 14 (2.4%) | 7 (1.1%) | 21 (1.7%) |

| Relationship strife | 14 (2.4%) | 25 (3.8%) | 39 (3.2%) |

| Incarceration | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.3%) | 3 (0.2%) |

| Control | Intervention | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 572) | (N = 662) | (N = 1234) | |

| Social pressures and supports: | |||

| Does not feel supported | 32 (5.6%) | 17 (2.6%) | 49 (4.0%) |

| Feels threatened | 28 (4.9%) | 20 (3.0%) | 48 (3.9%) |

| Feels pressured to have sex | 13 (2.3%) | 3 (0.5%) | 16 (1.3%) |

| Alcohol use: | |||

| Does not drink alcohol | 436 (76.2%) | 533 (80.5%) | 969 (78.5%) |

| Drinks alcohol | 110 (19.2%) | 129 (19.5%) | 239 (19.4%) |

| Missing | 26 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) | 26 (2.1%) |

| Other Substance use: | |||

| Uses other (e.g., marijuana) | 6 (1.0%) | 12 (1.8%) | 18 (1.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mwangwa, F.; Johnson-Peretz, J.; Peng, J.; Balzer, L.B.; Litunya, J.; Nakigudde, J.; Black, D.; Owino, L.; Akatukwasa, C.; Onyango, A.; et al. The Effect of a Life-Stage Based Intervention on Depression in Youth Living with HIV in Kenya and Uganda: Results from the SEARCH-Youth Trial. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10020055

Mwangwa F, Johnson-Peretz J, Peng J, Balzer LB, Litunya J, Nakigudde J, Black D, Owino L, Akatukwasa C, Onyango A, et al. The Effect of a Life-Stage Based Intervention on Depression in Youth Living with HIV in Kenya and Uganda: Results from the SEARCH-Youth Trial. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(2):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10020055

Chicago/Turabian StyleMwangwa, Florence, Jason Johnson-Peretz, James Peng, Laura B. Balzer, Janice Litunya, Janet Nakigudde, Douglas Black, Lawrence Owino, Cecilia Akatukwasa, Anjeline Onyango, and et al. 2025. "The Effect of a Life-Stage Based Intervention on Depression in Youth Living with HIV in Kenya and Uganda: Results from the SEARCH-Youth Trial" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 2: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10020055

APA StyleMwangwa, F., Johnson-Peretz, J., Peng, J., Balzer, L. B., Litunya, J., Nakigudde, J., Black, D., Owino, L., Akatukwasa, C., Onyango, A., Atwine, F., Arunga, T. O., Ayieko, J., Kamya, M. R., Havlir, D., Camlin, C. S., & Ruel, T. (2025). The Effect of a Life-Stage Based Intervention on Depression in Youth Living with HIV in Kenya and Uganda: Results from the SEARCH-Youth Trial. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(2), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10020055