Public Awareness of Rabies and Post-Bite Practices in Makkah Region of Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Data Collection and Instrument

2.3.1. Instrument Development, Translation, and Pilot Testing

2.3.2. Ethics and Consent

2.3.3. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Pet Dog Ownership

3.3. Community Dog Contact and Perceived Stray Burden

3.4. Dog Bite History and Immediate Response

3.5. Awareness, Attitudes, and Post-Bite Actions

3.6. Association Between Pet Ownership and Awareness Indicators

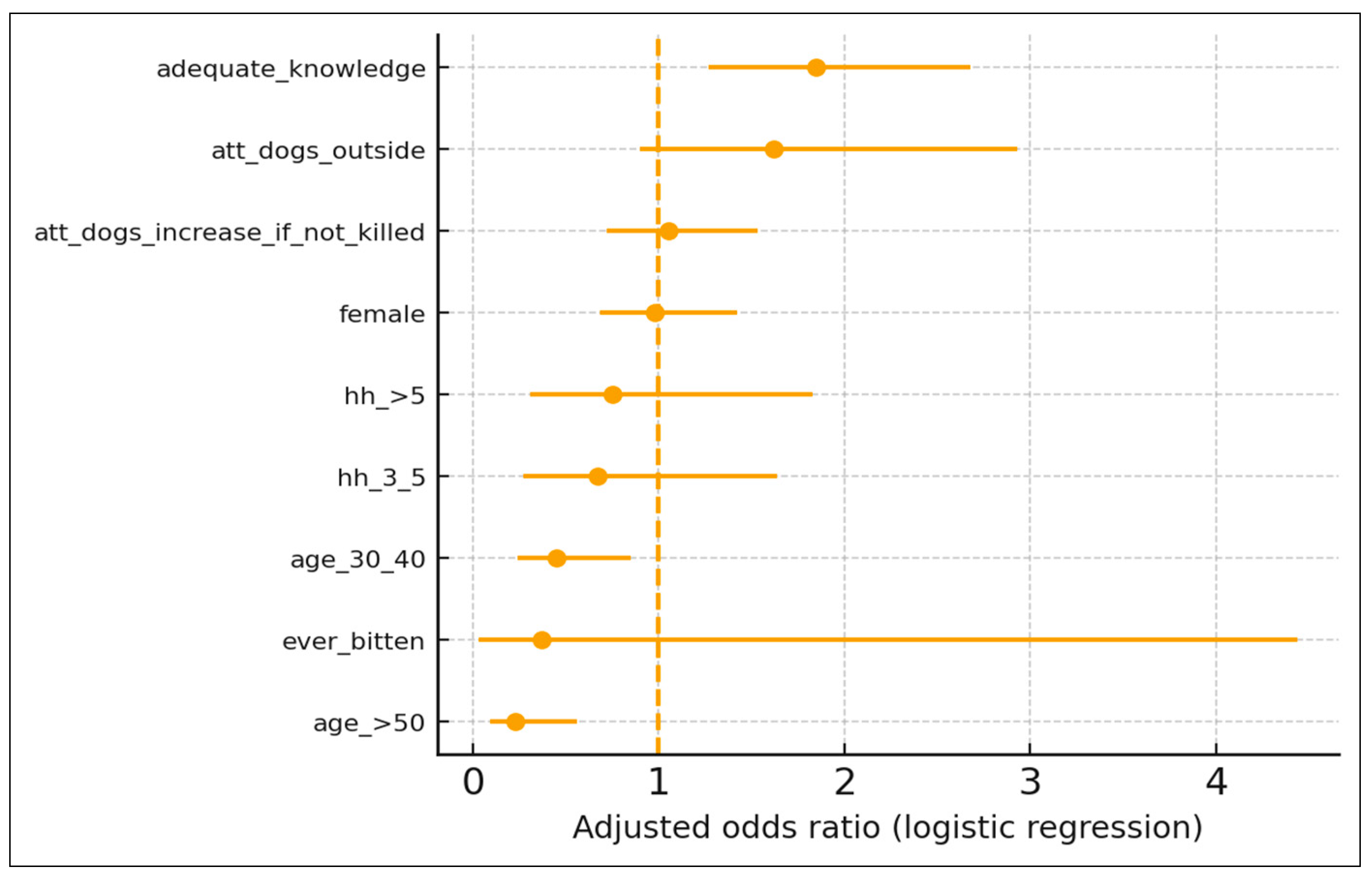

3.7. Predictors of Appropriate Intended Post-Bite Action

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Rabies: Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Katie, H.; Coudeville, L.; Lembo, T.; Sambo, M.; Kieffer, A.; Attlan, M.; Barrat, J.; Blanton, J.D.; Briggs, D.J.; Cleaveland, S.; et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fooks, A.R.; Cliquet, F.; Finke, S.; Freuling, C.M.; Hemachudha, T.; Mani, R.S.; Müller, T.; Nadin-Davis, S.; Picard-Meyer, E.; Wilde, H.; et al. Rabies. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghui, R.; Stone, M.; Semedo, M.H.; Nel, L. New global strategic plan to eliminate dog-mediated rabies by 2030. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e828–e829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH/OIE); Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Global Alliance for Rabies Control. Zero by 30: The Global Strategic Plan to End Human Deaths from Dog-Mediated Rabies by 2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513838 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Tidman, R.; Fahrion, A.S.; Thumbi, S.M.; Wallace, R.M.; De Balogh, K.; Iwar, V.; Yale, G.; Dieuzy-Labaye, I. United Against Rabies Forum: The first 2 years. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1010071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeaim, N.; Suwanwong, C.; Prasittichok, P.; Mohan, K.P.; Hudrudchai, S. Effectiveness of educational interventions for improving rabies prevention in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2024, 13, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A.; Assiri, A.M.; Gautret, P. Rabies in Saudi Arabia: A need for epidemiological data. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tayib, O.A. An Overview of the Most Significant Zoonotic Viral Pathogens Transmitted from Animal to Human in Saudi Arabia. Pathogens 2019, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetta, H.F.; Albalawi, K.S.; Almalki, A.M.; Albalawi, N.D.; Albalawi, A.S.; Al-Atwi, S.M.; Alatawi, S.E.; Alharbi, M.J.; Albalawi, M.F.; Alharbi, A.A.; et al. Rabies vaccination and public health insights in the extended Arabian Gulf and Saudi Arabia: A systematic scoping review. Diseases 2025, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.M.; Naeem, A.; Mshelbwala, P.P.; Dutta, P.; Hassan, M.M.; Elfadl, A.K.; Kodama, C.; Zughaier, S.M.; Farag, E.; Bansal, D. Epidemiology, transmission dynamics, risk factors, and future directions for dog-mediated rabies in the Arabian Peninsula: A review. Eur. J. Public Health 2025, 35 (Suppl. S1), i14–i22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Haider, N.; Bhowmik, R.K.; Rana, M.S.; Prue Marma, A.S.; Hossain, M.B.; Debnath, N.C.; Ahmed, B.N. Awareness of rabies and response to dog bites in a Bangladesh community. Vet. Med. Sci. 2016, 2, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouky, D.E.S.; Abu-Zaid, H. Mobile phone use patterns and addiction in relation to depression and anxiety. East Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 26, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, A.D. Translation and validation of study instruments for cross-cultural research. Gastroenterology 2004, 126 (Suppl. S1), S124–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper—April 2018. Weekly Epidemiological Record. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9316 (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- World Health Organization. Accelerating programmatic progress and access to human rabies vaccines and immunoglobulins. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2024, 99, 307–318. [Google Scholar]

- United Against Rabies. Global Monitoring and Evaluation of ‘Zero by 30’. 2024. Available online: https://unitedagainstrabies.org/global-monitoring-and-evaluation-of-zero-by-30/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Swedberg, C.; Bote, K.; Gamble, L.; Fénelon, N.; King, A.; Wallace, R.M. Eliminating invisible deaths: The woeful state of global rabies data. Front. Trop. Dis. 2024, 4, 1303359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyere, D.P.; Yaa, A.N.; Anthony, O.T.; Sakran, A.K.; David, K.; Solomon, O.; Gyan, L. Empowering dog owners and One Health teams to eliminate rabies: A community-Led approach from Techiman metropolitan, Ghana. One Health Outlook 2025, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memish, Z.; Ebrahim, S.H.; Brennan, R.; Kodama, C.; Haji-Jama, S.; Mollet, T.; Abubakar, A. Perspectives and future directions on the prevention and control of emerging and re-emerging vector-borne and zoonotic diseases: Findings from across the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. Eur. J. Public Health 2025, 35 (Suppl. S1), i1–i2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Against Rabies. Zero by 30: The Global Strategic Plan to End Human Deaths from Dog-Mediated Rabies by 2030. 2018–2025 Updates. Available online: https://unitedagainstrabies.org/publications/zero-by-30-the-global-strategic-plan-to-end-human-deaths-from-dog-mediated-rabies-by-2030/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- WHO South-East Asia. Rabies—Zero Deaths by 2030. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/rabies/rabies-zero-deaths-by-2030 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Mohanty, P.; Durr, S.; Heydtmann, S.; Sarkar, A.; Tiwari, H.K. Improving awareness of rabies and free-roaming dogs in schools of Guwahati, Assam, India: Exploring the educators’ perspective. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, J.; Zhou, S.; Zhan, Z.; Tang, J.; Wang, W.; Tang, H. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing Unmasks Atypical Rabies—Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China, 2024. China CDC Wkly. 2025, 7, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqatifi, W.H.; Alshubaith, I.H. Rabies epidemiology and health authorities efforts in control and prevention of the disease in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A narrative review. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 12, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Ministry of Health. Communicable Diseases—Rabies. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/HealthAwareness/EducationalContent/Diseases/Infectious/Pages/002.aspx (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Weber, A.S.; Turjoman, R.; Shaheen, Y.; Al Sayyed, F.; Hwang, M.J.; Malick, F. Systematic thematic review of e-health research in the Gulf Cooperation Council (Arabian Gulf): Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 23, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasem, S.; Hussein, R.; Al-Doweriej, A.; Qasim, I.; Abu-Obeida, A.; Almulhim, I.; Alfarhan, H.; Hodhod, A.A.; Abel-Latif, M.; Hashim, O.; et al. Rabies among animals in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Saudi Arabia—Traveler View: Rabies. 2025. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/traveler/none/saudi-arabia (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Gan, H.; Hou, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Lin, R.; Xue, M.; Hu, H.; Liu, M.; et al. Global burden of rabies in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 126, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Category | n |

|---|---|---|

| Resident of Makkah Region | Yes | 509 (97.3%) |

| No | 14 (2.7%) | |

| Residence area | Makkah | 480 (91.8%) |

| Jeddah | 29 (5.5%) | |

| Al Laith | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Qunfudha | 3 (0.6%) | |

| Ta’if | 10 (1.9%) | |

| Gender | Male | 247 (47.2%) |

| Female | 276 (52.8) | |

| Household size | <3 | 27 (5.2%) |

| 3–5 | 159 (30.4%) | |

| >5 | 337 (64.4%) |

| A | ||

| Parameter | Category | n |

| Pet dog ownership | Yes | 10 (1.9%) |

| No | 513 (98.1%) | |

| B | ||

| Parameter | Category | n (% of owners) |

| Dogs cared for | <3 | 8 (80%) |

| 3–7 | 1 (10.0%) | |

| >7 | 1 (10.0%) | |

| Dog sex | Male | 6 (60.0%) |

| Female | 4 (40.0%) | |

| Dog age | Puppy | 2 (20.0%) |

| Adult | 8 (80.0%) | |

| Breed | Unknown | 5 (50.0%) |

| Border collie | 1 (10.0%) | |

| Chihuahua | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Caucasian | 2 (20.0%) | |

| Hybrid | 2 (20.0%) | |

| Source | Previous dog litter | 9 (90.0%) |

| Adoption from street | 1 (10.0%) | |

| Reason for ownership | Guarding (Yes) | 8 (80.0%) |

| Sterilization | Yes | 6 (60.0%) |

| Maybe | 4 (40.0%) | |

| Official registration | Yes | 3 (30.0%) |

| No | 7 (70.0%) | |

| A | |||

| Parameter | Category | n | % of owners |

| Ever cared for/fed community dogs | Yes | 6 | 60.0 |

| No | 4 | 40.0 | |

| B | |||

| Category | n (%) | ||

| None | 137 (26.2%) | ||

| I don’t know | 111 (21.2%) | ||

| 1–5 | 206 (39.4%) | ||

| 6–10 | 40 (7.6%) | ||

| 11–20 | 10 (1.9%) | ||

| >20 | 19 (3.6%) | ||

| Attacking Dog | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Stray | 2 (50.0%) |

| Own pet dog | 1 (25.0%) |

| Other’s pet dog | 1 (25.0%) |

| A | ||

| Item | Category | n (%) |

| Know what rabies is | Yes | 317 (60.6%) |

| Rabies is vaccine-preventable | Yes | 333 (63.5%) |

| Only way to get rabies is dog bite | Agree | 273 (52.2%) |

| Dogs should be kept outside | Agree | 469 (89.7%) |

| Dogs will increase if not killed | Agree | 265 (50.7%) |

| B | ||

| Action | n (%) | |

| Visit clinic/hospital for rabies vaccine | 493 (94.3%) | |

| Wash wounds | 316 (60.4%) | |

| Search for traditional treatment | 45 (8.6%) | |

| I don’t know | 29 (5.5%) | |

| Do nothing | 15 (2.9%) | |

| Sterilize the area (antiseptic only) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| C | ||

| Item | Category | n |

| Where vaccine is available | Hospital | 417 (79.7%) |

| Health center | 414 (79.2%) | |

| Pharmacy | 31 (5.9%) | |

| Perceived severity | Human deaths from rabies are high (Agree) | 162 (31.0%) |

| Animals die from rabies (Agree) | 306 (58.5%) | |

| Information source | Social media | 390 (74.6%) |

| Doctors | 216 (41.3%) | |

| TV | 94 (18.0%) | |

| Other | 21 (4.0%) | |

| General knowledge | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Awareness Item | Ownership = No (n = 513), n (%) | Ownership = Yes, (n = 10) n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Know what rabies is (Yes vs. No) * | 312 (60.8) vs. 201 (39.2) | 5 (50.0) vs. 5 (50.0) | 0.488 |

| Only way is dog bite (Agree vs. Disagree) | 265 (51.7) vs. 248 (48.3) | 8 (80.0) vs. 2 (20.0) | 0.076 |

| Human deaths high (Agree vs. Disagree) | 159 (31.0) vs. 354 (69.0) | 3 (30.0) vs. 7 (70.0) | 0.946 |

| Animals die (Agree vs. Diagree) | 302 (58.9) vs. 211 (41.1) | 4 (40.0) vs. 6 (60.0) | 0.230 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hariri, N.H.; Alrougi, K.S.; Almogbil, A.A.; Kassar, M.H.; Alharbi, R.G.; Krenshi, A.O.; Altayyar, J.M.; Alibrahim, A.S.; Alandiyjany, M.N.; Bashal, F.B.; et al. Public Awareness of Rabies and Post-Bite Practices in Makkah Region of Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10120337

Hariri NH, Alrougi KS, Almogbil AA, Kassar MH, Alharbi RG, Krenshi AO, Altayyar JM, Alibrahim AS, Alandiyjany MN, Bashal FB, et al. Public Awareness of Rabies and Post-Bite Practices in Makkah Region of Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(12):337. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10120337

Chicago/Turabian StyleHariri, Nahla H., Khalid S. Alrougi, Abdullah A. Almogbil, Mona H. Kassar, Reman G. Alharbi, Abdullah O. Krenshi, Jory M. Altayyar, Abdullah S. Alibrahim, Maher N. Alandiyjany, Fozya B. Bashal, and et al. 2025. "Public Awareness of Rabies and Post-Bite Practices in Makkah Region of Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 12: 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10120337

APA StyleHariri, N. H., Alrougi, K. S., Almogbil, A. A., Kassar, M. H., Alharbi, R. G., Krenshi, A. O., Altayyar, J. M., Alibrahim, A. S., Alandiyjany, M. N., Bashal, F. B., Bawahab, N. S., Saleh, S. A. K., & Adly, H. M. (2025). Public Awareness of Rabies and Post-Bite Practices in Makkah Region of Saudi Arabia: Cross-Sectional Study. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(12), 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10120337