Abstract

Blended learning has introduced a more accessible and flexible teaching environment in higher education. However, ensuring that content is inclusive, particularly for students with learning difficulties, remains a challenge. This paper explores how Moodle, a widely adopted learning management system (LMS), can support inclusive and adaptive learning based on Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles. A 16-week descriptive exploratory study was conducted with 70 undergraduate students during a software engineering fundamentals course at Philadelphia University in Jordan. The research combined weekly iterative focus groups, teaching reflections, and interviews with 16 educators to identify and address inclusion barriers. The findings highlight that the students responded positively to features such as conditional activities, flexible quizzes, and multimodal content. A UDL-based framework was developed to guide the design of inclusive Moodle content, and it was validated by experienced educators. To our knowledge, this is the first UDL-based framework designed for Moodle in Middle Eastern computing and engineering education. The findings indicate that Moodle features, such as conditional activities and flexible deadlines, can facilitate inclusive practices, but adoption remains hindered by institutional and workload constraints. This study contributes a replicable design model for inclusive blended learning and emphasizes the need for structured training, intentional course planning, and technological support for implementing inclusivity in blended learning environments. Moreover, this study provides a novel weekly iterative focus group methodology, which enables continuous course refinement based on evolving students’ feedback. Future work will look into generalizing the research findings and transferring the findings to other contexts. It will also explore AI-driven adaptive learning pathways within LMS platforms. This is an empirical study grounded in weekly student focus groups, educator interviews, and reflective teaching practice, offering evidence-based insights on the application of UDL in a real-world higher education setting.

1. Introduction

Information technologies have evolved dramatically in the last few decades, making many changes in our lives. Education is one of the domains that has been significantly impacted. With this rapid change, higher education institutions started integrating technologies such as e-learning and mobile learning into their systems [1,2].

E-learning implies delivering educational content and services through digital technologies, either fully online or blended. Blended learning is an ideal solution for improving the quality of learning, and it is increasingly used in higher education [3]. It integrates face-to-face teaching with online learning, which fosters a supportive and interactive environment that encourages students to participate and reduces anxiety around making mistakes [2].

Learning management systems (LMSs) play a vital role in education when using fully online and blended learning teaching models. Higher education institutions adopted LMSs like Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment (Moodle) [4] and Blackboard to facilitate the learning and teaching process. Moodle enables lecturers to monitor the automated log reports, which show when students have completed their assignments and the time spent on the quiz or the assignment, monitor forums, and facilitate course management. This introduced many benefits; however, it also introduced many challenges specifically related to content development, the suitability of the content delivered to students, and the inclusion of all students, without leaving some of them behind. However, while LMSs are widely spread and adopted, few studies focus on how such platforms support inclusivity and adaptivity in blended learning environments [5,6].

A key principle of modern educational systems that aims to guarantee fair chances for all students while taking into account their various needs is inclusive education [7]. A significant portion of all higher education institutions have students with learning difficulties, and when creating online educational content, educators should consider these students’ needs through user-friendly design and adaptive tools that have the potential to create an effective learning environment.

The use of blended learning to enhance teaching and learning has been the subject of many previous studies, but few studies have examined how educational technology employed for blended learning may be utilized to foster inclusion in these settings. A review by [8] identified that studies on blended learning focus on understanding and outcomes of blended learning rather than on inclusivity of the used tools. Furthermore, ref. [9] identified that UDL and assistive technologies require more research in the context of blended learning. From our review of the literature, we have noticed that within the higher education context, most research focuses on aspects other than inclusivity. To contribute to bridging the gap in the literature, in this paper, we evaluate Moodle (the official LMS used at Philadelphia University) for its suitability for delivering inclusive and adaptive content to students in a blended learning environment. Thus, our paper aims to answer the following research questions:

- How can Moodle be used to support inclusive and accessible learning experiences for students with diverse needs and challenges in blended learning environments?

- What are the available features in Moodle that can promote inclusive and adaptive blended learning?

- How is the role of Moodle in inclusive blended learning perceived by educators in Jordanian higher education institutions?

- What are the challenges in investing in Moodle for achieving inclusive education, and how to deal with such challenges?

A descriptive exploratory investigation incorporating primary and secondary data was used to answer our research questions. Following that, we developed an inclusive and adaptive learning UDL-based framework, which was also evaluated by some educators through interviews. Our framework can help evaluate the capacity of any LMS to provide inclusive and adaptable material. We addressed the gap in the literature on inclusive digital learning environments, as, to the best of our knowledge, this framework is the first UDL-based framework that is explicitly designed for use with Moodle in computing and engineering sciences in the Middle East. Furthermore, the weekly iterative focus group model was designed and employed by the first author which enabled real-time responsiveness to students’ feedback. This supported continuous improvements of the course content throughout the semester. Unlike speculative or conceptual studies, our investigation is grounded in empirical data collected throughout the semester from iterative student focus groups, educator interviews, and the first author’s teaching reflections. These sources were used to systematically evaluate and adapt course content to support inclusivity and accessibility. The utilized “Fundamentals of Software Engineering” course followed a flipped classroom model, where students first engage with new material via two in-person lectures, followed by asynchronous engagement utilizing videos and assignments on Moodle. These videos and assignments are central to learning and assessment and not supplementary; they provide new material that help to deepen conceptual understanding. Thus, this paper contributes to the field by documenting a real-world implementation and a practice-based case study of inclusive and adaptive course design in an undergraduate software engineering course. We integrated the UDL principles into weekly teaching materials, assessment, and student engagement strategies.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: The literature review and research background are presented in Section 2. The research methodology is described in Section 3. Results are provided in Section 4 and discussed in Section 5. Conclusions, recommendations, and future work are presented in Section 6.

2. Literature Review and Research Background

Section 2 reviews the literature and the research background relevant to this study. It is structured into three subsections. Section 2.1 introduces the concept of blended learning, its models, and benefits in higher education. Section 2.2 explores alternative learning environments, focusing on Moodle as a LMS that supports adaptive learning. Section 2.3 discusses the UDL framework and its application in inclusive education, particularly in technology-supported contexts. Thus, the section provides a comprehensive foundation for understanding the study’s focus on designing inclusive and adaptive content in Moodle.

2.1. Blended Learning and Blended Learning Models

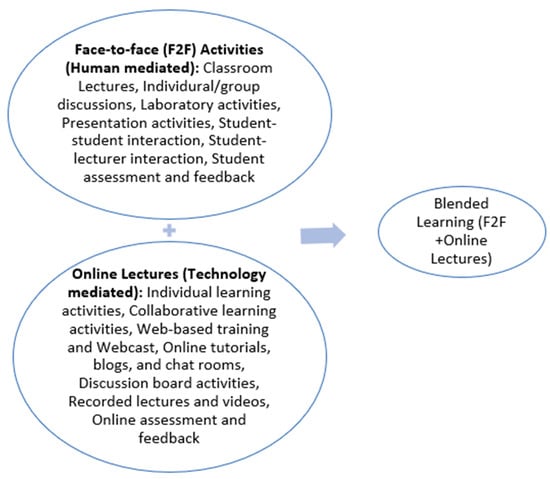

Blended learning combines face-to-face and online learning, as shown in Figure 1. The use of blended learning is increasing among higher education institutions around the world because of its benefits in combining traditional and online teaching methods [10,11,12]. Blended learning brought many models that incorporate in-person and online learning, which may greatly improve the learning process, personalize learning, enhance students’ learning engagement, and improve students’ experience [13,14]. Therefore, employing blended learning facilitates students’ commitment and engagement in the learning process by shifting educators’ attention from teaching to learning [15].

Figure 1.

Blended learning concept [16].

According to [11], blended learning is the most promising teaching strategy for the future. Poon [11] ensured that emphasis should be on how to successfully apply it so that its advantages may be achieved. By combining face-to-face and online learning, this approach enables educators to meet pedagogical goals related to student skill development and improve their teaching qualities [17].

Blended learning has various initiatives that combine 30% of face-to-face interaction with 70% of IT-mediated learning [18]. In the same way, ref. [19] recommended integrating 20% face-to-face teaching with 80% online learning for successful blended learning. Thus, blended learning has many approaches and delivery models.

Personalized learning plays a critical role in transferring the focus of higher education from a teacher-centred environment to a learner-centred environment [20]. In their study, the authors of [21] highlighted the importance of personalized learning in reducing the gaps in learning and practices among students and helping to enhance students’ skills. This aligns with the objectives of blended learning as it enhances personalization and promotes the growth of self-directed learning, which boosts communication between learners and educators as well as amongst learners [22].

Blended learning facilitates access to online resources that provide opportunities for professional collaboration and enhance the adaptability of lectures [23,24]. It also provides students with skills to study at their own pace [25]. However, it faces some challenges, such as insufficient professional development, limited technical resources, and inadequate internet connections [12].

The flipped classroom model is a widely studied form of blended learning in which students engage with instructional content independently (often via videos or readings) before participating in interactive, face-to-face sessions that focus on problem-solving, discussion, or application [26]. This model has been shown to promote active learning, improve student engagement, and allow for differentiated instruction [27,28]. In the context of higher education, flipped learning has also been associated with better academic performance and increased learner autonomy [29]. Our course design adopts this approach and further adapts it using UDL principles to ensure accessibility and inclusivity for students with diverse learning needs.

2.2. Alternative Learning Environments to Traditional Classrooms in Education

Online systems were found to have the capacity to provide platforms with competitive practices that offer alternatives to real-life educational settings, which support students’ learning and improve the quality of learning [30]. Among these systems, Moodle was and still is one of the most popular learning management platforms because of its flexibility as an open source and cost-effectiveness. However, these systems have affected learning environments and teaching pedagogies [31].

Adaptive learning aims to provide learners with the tools they need to learn based on their particular cognitive characteristics and needs [6]. The authors of [6] also added that it is crucial to consider the learners’ current level of knowledge as well as individual demands and variations in learning styles. Moodle is one of the tools for implementing adaptive learning. Although it is not inherently adaptive, it is possible to design adaptive activities within Moodle. It offers a variety of adaptive learning solutions, allowing educators the resources they need to support learners at every step of the learning process, from content delivery to assessment [6]. For example, the authors of [6] demonstrated how Moodle is used at Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University and, therefore, how Ukrainian higher education institutions utilized Moodle to implement adaptive learning through the conditional release of content, role-based access, and analytics-informed decisions. Similarly, ref. [4] noted that Moodle’s flexibility fosters a more student-centered learning environment when appropriately configured.

Furthermore, a study by [3] at Misr University for Science and Technology (MUST) demonstrated that Moodle-based blended learning has the potential to significantly improve university students’ writing performance. This ensures that the design features of Moodle allow for iterative feedback, tracking, and multimodal input. In other words, such design features are consistent and important to inclusive and adaptive pedagogy.

Thus, Moodle does not have automated tailored content; therefore, it is not inherently adaptive. The platform supports teacher-driven adaptivity, which is equally critical in real-time blended learning environments. Such capability aligns with UDL’s principles of providing multiple means of representation, action, and engagement. Thus, there is a need for further investigation and empirical evaluation.

2.3. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Inclusive Learning

To accommodate the various needs of students, the Centre for Applied Special Technology (CAST) originally proposed UDL in the 1990s [32]. By using UDL, all students may benefit from an inclusive and accessible learning environment [33,34]. The objective of lesson planning from a UDL viewpoint is to replace the “one size fits all” teaching approach that is based on an imagined “standard learner” with an already accessible curriculum that takes into account the individual differences among all students [35]. This variation is a reflection of the three brain networks that are involved in learning: (1) the recognition networks that are involved in understanding and interpretation of environmental information; (2) the strategic networks that are in charge of organizing and planning skills and procedures; and (3) the affective networks that have an impact on learner motivation and engagement [35]. The core concept of UDL is the idea that these three learning networks should be addressed with flexible solutions. These three aspects are demonstrated in practice through standards and assessments that motivate educators to offer various channels for representation, communication, behavior, and engaging students in different activities [33,34].

Many research studies have confirmed that UDL may be used in a wide range of educational levels, from young children [36] to students with special education needs [37,38], students who do not have special educational needs [39,40], and even university students [41].

Thus, UDL has been found by researchers to have a positive effect at different educational levels. This framework promotes the structured development of instructional environments that effectively address the diverse needs of an increasingly diverse student population in online education contexts [42]. This paper utilizes UDL in the proposed framework and applies UDL principles to achieve inclusivity in the blended learning environment.

Many studies have explored Moodle’s technical capabilities and its general pedagogical utility [4,13]. Recent studies have also explored intelligent adaptations within Moodle environments. For instance, ref. [43] proposed an unobtrusive method to model learners’ personalities using learning analytics and Bayesian networks in an intelligent Moodle (iMoodle) system, showing promising results in predicting personality dimensions and therefore enhancing the personalization of learning experiences.

It can be seen that few studies have explored how Moodle’s features can be systematically aligned with UDL principles to meet diverse learners’ needs in real classroom settings. This observation is supported by [6], who note that most applications of adaptive learning in Moodle remain manual and lack standardized evaluation frameworks grounded in UDL.

Recent studies have also evaluated Moodle’s effectiveness in supporting accessibility and usability for learners with difficulties. Thus, the Moodle platform has been analyzed in different distribution versions regarding accessibility and compliance with standards [44,45]. Since then, the scope of evaluation has evolved from basic accessibility checks to broader usability studies, examining how well Moodle accommodates user satisfaction, navigation, and content interaction for students with functional diversity. For example, ref. [46] conducted a comprehensive usability study of Moodle for students with functional diversity. Their work assessed how well Moodle met accessibility standards and user needs. They focused on user satisfaction, navigation, and functional adaptation.

However, while these studies provide essential technical insights, they often do not engage with UDL-based instructional design or propose comprehensive frameworks for content adaptation that address learner variability. Such studies provide valuable insights into the user experience of learners with special needs; however, they do not provide actual design frameworks for adapting learning content itself. Our study attempts to bridge this gap by proposing a structured approach to designing both inclusive and adaptive Moodle content tailored to student diversity in higher education, especially within the Arab educational context. This is because the existing literature is dominated by studies conducted in Western or East Asian contexts, while empirical investigations from the Middle East, and Jordan in particular, remain under-represented. Given the increasing reliance on blended learning in Jordanian higher education, this geographic and methodological gap highlights the urgent need for context-specific studies that evaluate the use of Moodle for inclusive education through structured, field-based methodologies.

Our review of the literature has shown that there is a growing adoption of LMS in higher education. However, there is limited empirical research that evaluates how Moodle supports inclusivity and adaptivity from a UDL perspective. The authors of [47] specified that when selecting strategies to implement UDL, it is advisable to introduce its principles gradually—beginning with the replacement of less effective activities—to maintain enthusiasm and engagement among both students and teachers.

Our paper addresses this gap by systematically analyzing Moodle’s features in a real teaching environment using focus groups, reflective practices, and educator interviews, aiming to uncover how Moodle can be operationalized as an adaptive and inclusive platform that supports all learners. We propose a framework for designing inclusive and adaptive Moodle content. Our framework is informed by actual classroom experience and feedback from both students and educators. The framework is then utilized to evaluate Moodle for inclusivity and adaptivity.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

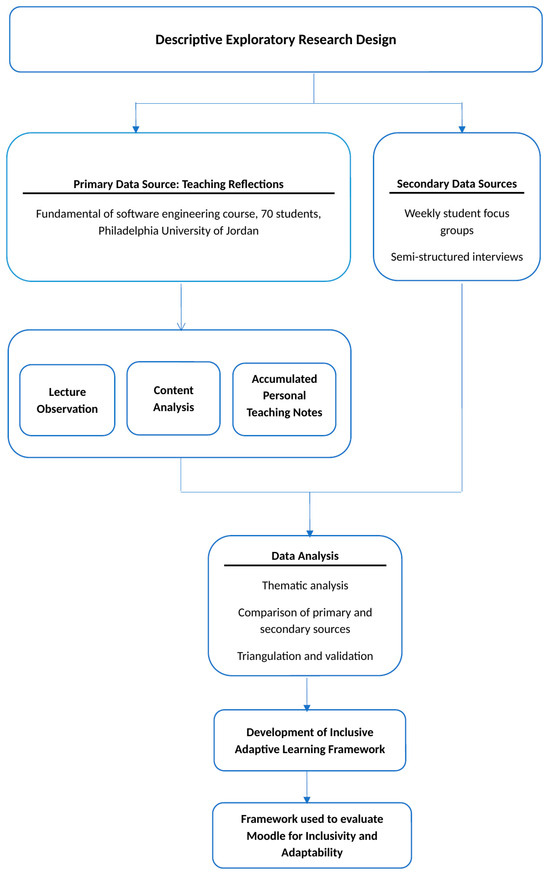

We adopted a descriptive exploratory qualitative design to investigate how Moodle can be utilized to achieve inclusive and adaptive learning in the context of higher education in Jordan. Such descriptive exploratory design is suitable for this unexplored area of educational technology where the goal is to understand a phenomenon from participants’ perspectives to generate a framework [48]. Figure 2 shows the research design approach, which incorporates reflective and thematic analysis, content analysis of course design, and thematic analysis of educators’ and students’ feedback. This multi-method qualitative approach allows for triangulation across different sources, which enriches the context and increases its depth and flexibility [49].

Figure 2.

Descriptive exploratory qualitative design.

Reflective analysis of the first author’s teaching experiences was a key component. Reflection is considered a valid method in practice-based educational research, as reported by [50]. Furthermore, it is considered valid and insightful when specifically exploring inclusive pedagogies [51].

3.2. Data Collection and Participants

Table 1 shows the details of the participants involved in the study, including demographics and experience. The “Fundamentals of Software Engineering” course is a second-semester course taught to first-year undergraduate students in the Software Engineering department. During the academic year 2024/2025, 70 students were enrolled in this course, which was delivered in two parallel sections: Section 1, with 42 students, and Section 2, with 28 students. Both sections followed the same curriculum and were taught by the same lecturer, utilizing identical teaching methods, Moodle resources, and assessment strategies. Therefore, the 70 students enrolled in the course and participated in the weekly focus groups described in this study. On the other hand, educators’ perspectives were gathered from both Philadelphia University and the University of Jordan as another Jordanian university in which Moodle is used as well, student data were limited to the course implementation only. The first author, with extensive experience in inclusive and blended learning design, delivered the course and led the weekly focus groups. The second author, a recognized expert in inclusive education, validated the instructional strategies and methodological framework to ensure their alignment with UDL principles. While a cross-institutional student comparison could be pursued in future work, this study aimed to provide a grounded, empirically supported investigation into inclusive blended learning practices within Jordanian universities settings. We selected educators who are familiar with Moodle and who delivered courses utilizing a blended learning approach. We employed purposeful sampling to ensure relevant experience with blended learning and Moodle [52]. Multiple sources were combined to enable methodological triangulation and to improve credibility, reliability, and scientific accuracy of our results [53].

Table 1.

Participant demographics and experience.

3.2.1. Primary Sources: Teaching Reflections and Observations

We utilized the first author’s accumulated personal teaching notes, content analysis, forum observations, and reflections recorded during teaching and assignment delivery. These reflections provided first-hand insights into how students engaged with the Moodle environment and how different learning materials and tools were received. The lecture observations and forum monitoring offered real-time insights into student behavior and classroom dynamics.

Furthermore, the content analysis enabled us to evaluate the inclusivity and adaptability of the course design by examining recurring expressions related to perceived accessibility, flexibility, clarity, and emotional support. These observations were systematically mapped to the UDL framework—specifically, the principles of providing multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression [3]. Coding and organizing the data was undertaken manually in a careful manner, which allowed patterns to emerge. This indicated the degree to which Moodle-supported elements aligned with inclusive teaching practices.

This approach aligns with an autoethnographic method, where personal experience is systematically analyzed to understand broader cultural and pedagogical phenomena [54]. This autoethnographic and observational data have the potential to help uncover real-time dynamics in inclusive teaching [54].

3.2.2. Secondary Sources: Student and Educator Feedback

To complement the primary data collected through structured teaching reflections, we systematically gathered additional qualitative data through weekly student focus groups and interviews with educators. We conducted both feedback processes through a rigorous approach; however, we consider them to be secondary sources in the context of our study because their primary role was to support and validate the insights drawn from the teaching reflections. This section summarizes the key themes that emerged from these supplementary sources.

- Weekly Student Focus Groups

We need student input from different kinds of learners to determine to what level Moodle has facilitated, or was an obstacle to, their learning experience. The focus groups involved open-ended interviews with students and were conducted to obtain a more in-depth analysis of the findings. Utilizing focus groups helped us to collect direct student feedback on the approach used for blended learning.

We conducted a focus group session of 15 min every week after the first face-to-face lecture to investigate students’ views and experiences with respect to each weekly designed piece of content. The focus groups were conducted in the classroom. The focus group sessions focused on obtaining student feedback on the content.

Students’ responses were used to build a solution that mitigates the challenges, which was then evaluated using the next weekly focus group. We believe that undertaking weekly, short, interactive brainstorming sessions is better than one-time surveys or interviews. This is because we can track the changes in how our students perceive the content and the approach over time. Moreover, iterative enhancements in delivering the content are enabled, which allows us to evaluate and compare different models and to identify the challenges in comprehending the content and the approach. Additionally, this enables us to understand and evaluate to what extent the assignment provided can support different learning needs. We were able to notice and monitor those students who were struggling and to plan group work with a view to engaging all students who were not able to finish the tasks on an individual basis. Having weekly focus group sessions provided continuous dynamic feedback, which allowed us to make refinements on both course content and delivery to meet students’ needs. Using this approach allowed us to monitor changes in student perceptions, which has the potential to provide a clearer picture of how inclusive practices were understood.

Furthermore, such planned group work enabled a reduction in missed deadlines, where we noticed decreased late submissions. Also, with respect to completion rates, we noticed improvement in comparison with the previous scenario of failing to submit individual assignments.

Concerning students’ satisfaction, during the iterative focus groups, students expressed their satisfaction and confidence in the lecturer’s support throughout the learning process.

Our focus groups involved 70 registered students, as explained previously. All students voluntarily participated, wherein their participation was considered a normal course interaction process to improve the blended learning content and approach, and they were told that their feedback would not affect their marks; it was only to enhance the content. By conducting these weekly focus groups, we were able to tailor content format, collaborative opportunities, and engagement. We did not record these discussions to encourage open, interactive discussions; however, the first author, who is the lecturer, documented the notes for later thematic analysis. Thus, using these focus groups helped us to encourage all students to participate in designing inclusive content.

Thus, to systematically analyze how Moodle supported inclusion and accessibility, students’ feedback during the focus groups was thematically coded in light of the UDL framework. Particularly, we examined their input in relation to key UDL principles, such as providing multiple means of representation (e.g., multimedia content), action, expression (e.g., flexible deadlines and group submissions), and engagement (e.g., emotional support via messaging and feedback). This mapping allowed us to identify patterns on how different learners—specifically those who reported struggles with workload, digital access, or learning pace—experienced the course design. Although we did not explicitly organize student groups based on diagnosed learning difficulties, our approach captured and addressed a wide spectrum of accessibility needs as they emerged organically from classroom interactions.

- 2.

- Educator Interviews

The educator interview method was selected to address the second and third research questions regarding Moodle’s support of inclusivity and adaptability. Furthermore, we investigated how design strategies align with inclusive pedagogical frameworks through interviews. Thus, we conducted 16 interviews with educators to evaluate their understanding of inclusive blended learning and their familiarity and perceptions regarding Moodle’s features to support diverse learners- interview questions are shown in Appendix A. Moreover, we discussed the challenges that educators face in familiarizing themselves with such tools and the challenges that hinder achieving inclusive blended learning in higher education. The 16 educators interviewed in this study were not involved in teaching or managing the specific course under investigation. Instead, they were selected based on their expertise in inclusive education and their experience using Moodle or similar LMS platforms in Jordanian higher education. Their feedback was used to validate the inclusive teaching strategies applied by the first author and to provide broader insights that informed the framework presented in this study.

We used semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative insights from educators, as interviews allow deeper investigation of educators’ observations. Moreover, interviews provide educators with the flexibility to elaborate on the challenges and solutions they have faced. This can provide first-hand insights into the perceptions of inclusive blended learning among educators in Jordanian higher education. Therefore, utilizing semi-structured interviews complemented students’ feedback from the focus groups and gave sufficient secondary data. Thus, the analysis of the interviews was critical for triangulating students’ perspectives and content analysis.

The interviewed educators were from two higher education institutions (eight from Philadelphia University and eight from the University of Jordan). All educators have experience with blended learning as they were chosen after making sure that all of them have delivered a blended learning course at least two times. We also ensured that the interviewed educators knew the basics of inclusivity in teaching.

We invited educators for the interviews and selected the 16 interviewees to ensure diversity in disciplines and backgrounds, opting not to focus on the faculty of information technology. All the participants voluntarily participated in the interviews, which were conducted openly, ensuring that the interviewees felt comfortable during the interviews so as to encourage honest feedback.

Each semi-structured interview was conducted face-to-face, with each interview ranging from 20 to 30 min in length. We first asked about the educators’ understanding of inclusive and adaptive blended learning. Then, we asked about the familiarity of the tools that enable inclusive and adaptive learning in Moodle. Finally, we asked about the challenges that they faced while integrating Moodle for inclusive and adaptive learning.

We took notes during the interviews and promptly summarized them at the end of each session. Ten of the participants chose not to allow the interview to be recorded, while six of them agreed to have audio recordings and transcripts created for the interviews. For those ten who rejected the recording, we relied on note-taking.

To conclude, our research explored the challenges, experiences, and adaptive strategies related to inclusive education in a blended learning environment. Weekly focus groups provided flexibility for exploring students’ and educators’ experience with Moodle in depth. We chose this qualitative approach over a quantitative one to obtain rich, context-sensitive insights into how inclusion and adaptability were implemented and experienced throughout the course.

3.3. Data Analysis

We employed thematic analysis [55,56] to analyze the results from teaching reflections, content analysis, and classroom observations. The first author summarized the weekly teaching reflections to identify the recurring challenges. The second author’s experience in inclusive learning was used to revise the challenges and to identify the Moodle content features that help to achieve inclusivity. We coded the features of Moodle that help to achieve adaptive and inclusive learning based on students’ engagement levels.

We also utilized thematic analysis to specify the recurring themes in students’ feedback. We selected this approach because it is flexible and suitable for exploring the research questions related to inclusion and adaptivity. The key insights were documented immediately after each brainstorming session to avoid recall bias, where the focus was to identify student engagement trends, to specify the challenges faced while completing the assignments and quizzes, and finally, to collect suggestions for improvements to achieve inclusivity.

We started by familiarizing ourselves through repeated readings of the transcripts and reflective notes. An inductive approach was utilized to generate the initial codes, guided by concepts from the UDL framework. The coding process was conducted in three phases: (1) open coding to capture meaningful data segments; (2) axial coding to group related codes; and (3) theme development and refinement to identify higher-level patterns.

Themes were identified based on frequency and relevance to the research questions. We collaborated to review and refine the themes. Having many discussions between the researchers ensured internal coherence and analytical clarity. This iterative process ensured that the resulting themes accurately represented participants’ experiences and aligned with the study’s focus on inclusive and adaptive learning practices in Moodle-based blended learning environments.

We compared the recurring themes across multiple weeks to monitor how they change over time and to ensure consistent feedback, which assures the validity of our study.

After completing the analysis, we specified the following themes: content-related challenges, accessibility-related challenges, and technical difficulties.

We used thematic analysis to identify the themes in educators’ responses during the interviews. We transcribed and summarized the key points after each interview; then, we performed the initial coding and specified the major themes as awareness of inclusive adaptive learning principles, challenges in engaging Moodle for inclusive and adaptive learning, identifying the barriers to achieving inclusivity, and finally, the recommendations to achieve inclusivity in blended learning.

3.4. Triangulation Strategy

We then specified the frequency of each issue and the shared concerns among participants. After that, we compared the results with students’ feedback to specify the gaps between educators’ approaches and students’ needs. We ensured different perspectives by including educators from various disciplines who have different levels of expertise in using Moodle. We adopted a methodological triangulation strategy by collecting and analyzing data from different primary sources to ensure consistency, reliability, and greater accuracy [53]. Weekly student reflections and focus group transcripts, the first author’s autoethnographic teaching notes and observations, and semi-structured interviews with educators were the main sources used. Following this approach and drawing on these resources allows us to compare different perspectives on how Moodle facilitated inclusive and adaptive learning in a blended learning environment.

We followed the triangulation protocol established by [57], starting by sorting and separating the data. Then, convergence coding was used to compare the findings in terms of the meaning and interpretation of themes. Later, convergence assessment was accomplished, followed by completeness assessment. Finally, research comparison and feedback were conducted to finish the triangulation process.

For the secondary data, we also cross-checked educators’ responses with student feedback and content analysis to ensure validity. Utilizing qualitative methods provided us with rich, contextual data that cannot be obtained through quantitative methods such as surveys.

3.5. Fundamentals of Software Engineering Course

In Jordanian higher education institutions, the academic year begins with the first semester (Fall), which runs from October to February, followed by the second semester (Spring), which runs from March to July. According to the academic study plan, the “Fundamentals of Software Engineering” course is typically undertaken by students in their second semester of study (i.e., in the spring semester of their first year). However, students may register for the course in either semester depending on course availability. In the case examined in this study, the course was delivered during the first semester of the 2024/2025 academic year, from October 2024 to February 2025. The course is delivered by the first author to the first-year students in their second semester. The blended learning (BL) model is used to deliver the course. Every course at Philadelphia University of Jordan follows the blended learning approach and incorporates the flipped classroom model as a core strategy. The course is taught utilizing two face-to-face, 50-min-long lectures per week for 16 weeks in addition to three short videos and a short assignment every week. The short videos were not presented during the face-to-face sessions; rather, they were made available to students on Moodle, where they could be accessed independently at home as part of the blended learning model. We followed the proposed framework for inclusive and adaptive content to ensure the inclusivity and adaptability of our course. Our course is designed and delivered based on this pedagogical framework. Thus, every face-to-face lecture has its goals, and every weekly video has its own goals where the learning outcomes are measured through solving problem-based assignments. Students acquire core concepts during the face-to-face lectures. They are then required to watch three videos to complete the individual problem-solving assignments. Students were informed of the goals and skills that they had to learn before starting with the videos and the assignment. Offering these videos ensures that students have the relevant resources, and providing students with special educational challenges with specific materials and occasionally having group assignments instead of individual assignments sometimes helps students to overcome the difficulties they face due to their special educational needs. The availability of the teacher for such students and the flexibility of asking questions made Moodle a suitable environment for inclusion in the blended learning model. It enhanced the collaboration between the lecturer and the students. Although in-person lectures accounted for the greater proportion of the instructional time (approximately 65%), the online content served as the primary source of new material, assignments, and student engagement. This aligns with flipped learning principles, where the online component initiates learning and classroom time is used to consolidate knowledge.

In [58], the authors emphasized the significance of evaluating current learning settings for appropriateness and taking into account the requirements of students with various impairments. Therefore, we systematically reviewed and analyzed the course materials for clarity, inclusivity, accessibility of the content, and their suitability for diverse students’ needs. Thus, it was evaluated for the inclusivity of multimedia materials and the ease of navigation. We evaluated the content for readability (color contrast, font size, etc.), multimodal learning support (alternative formats, availability of transcripts, etc.), and adaptive learning paths (flexible deadlines, conditional activities, etc.).

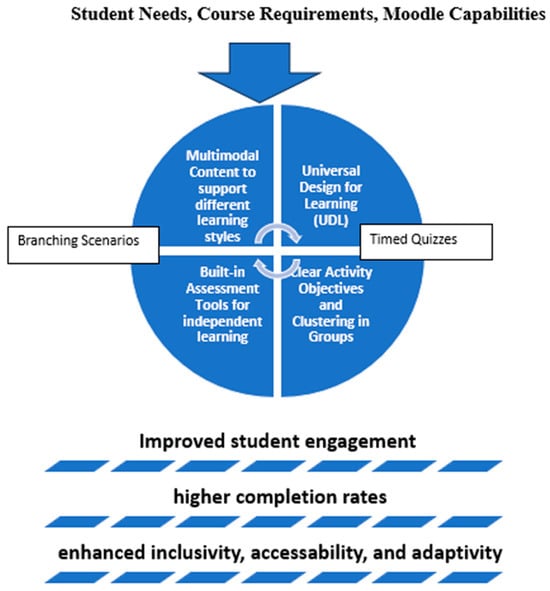

3.6. Development of a Framework of Inclusive and Adaptive Content

We established a framework for inclusive and adaptive content (Figure 3) to evaluate inclusivity and adaptability in Moodle. In our framework, we focus on maintaining clear activity objectives and multimodal content that has the potential to support multiple means of representation, which enables students to engage with material through visual and textual formats. Furthermore, we focus on maintaining built-in assessment tools to achieve independent learning.

Figure 3.

Framework for inclusive and adaptive content.

The framework described was developed after analyzing the data. It was not predefined or used during the coding process. Instead, it was created to summarize and organize the main themes that emerged from the analysis. An inductive process grounded in the thematic analysis of the data collected from student reflections, educator interviews, and teaching observations was used. Rather than beginning with a predefined model, we identified recurring patterns and organized them into three central areas: inclusive design practices, adaptive use of Moodle features, and ongoing feedback mechanisms. The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) guidelines informed our interpretation of the data but were not used as a base. To ensure the framework’s relevance and accuracy, we invited two participating educators to review the initial version and confirm that it aligned with their teaching experiences and course design choices.

We emphasized following the UDL, which provides a widely used comprehensive framework and principles for addressing students’ needs [59]. UDL aims to design an accessible learning environment that is challenging for all learners in which they can take responsibility for the learning process [60]. Employing UDL has the potential to support not only students with disabilities but all of the students in the classroom. UDL offers many ways to engage students and encourage their participation in the learning process. Moreover, UDL promotes providing multiple sources and means of representation, where learners can choose among the available resources. We chose these principles because they are related to technological integration, which is relevant to our study. Educators can benefit from technology through the provision of multiple data forms, such as text, videos, and diagrams. Any used technology should be evaluated for its capacity to provide multiple sources and representations of data to suit various learners’ needs.

The framework for inclusive and adaptive content is utilized to evaluate Moodle for inclusivity and adaptability. Furthermore, it can be used for evaluating any LMS.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

Although we had ethical clearance to conduct this research, we did not collect any personal information, and students voluntarily participated. Students participated in normal classroom settings to ensure that they were not stressed or forced to discuss the topics and give feedback. Thus, all students felt comfortable in the blended learning settings. Therefore, we maintained student confidentiality and adhered to educational and academic research ethics.

4. Results

This section presents the results of our research, which reflect student responses to the inclusive and adaptive teaching strategies implemented throughout the course, including different content styles, flexible submission formats, and structured weekly engagement through Moodle.

4.1. Teaching Reflections, Focus Groups, and Interviews Codes

The teaching reflections, insights from focus groups, and the resulting codes and themes are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Thematic code table from teaching reflections, focus groups, and interviews

After analyzing the notes and transcripts from the focus group sessions, reviewing the teaching reflections, and analyzing the interview transcripts, we organized the results into the codes demonstrated in Table 2. From the codes, we began to see some emerging themes. We then categorized the codes into the following themes, which are also shown in Table 2:

- Barriers for engaging learners in blended learning environments: This theme identified the challenges related to the participation and engagement of students in blended learning settings, such as the strict deadlines and content consumption levels in Moodle.

- Learning preferences and adaptive learning: This theme explains how adaptive content could enhance inclusivity in a blended learning environment.

- Educators’ perceptions of Moodle’s adaptability and inclusivity features: This theme analyses Moodle from the viewpoints of Jordanian educators.

- Educators’ readiness and preparedness: This theme focuses on the ability of educators to learn the adaptability and inclusive features available in Moodle, where it has two perspectives, namely, the usability of Moodle and the time available for educators to learn with the workload they have.

- Best practices for designing inclusive and adaptive blended learning: This theme focuses on providing recommendations for enhancing inclusivity using features available in Moodle.

4.2. Adaptive Inclusive Learning in Moodle

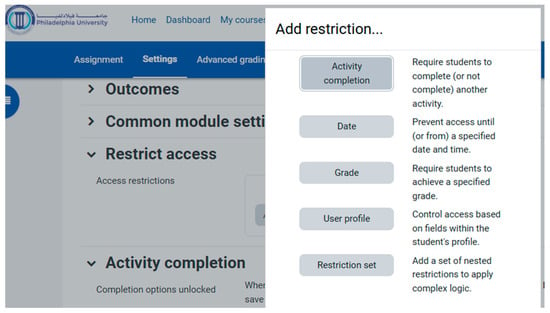

Even though Moodle does not directly offer personalized, inclusive learning or adaptation, it might facilitate inclusive and adaptive learning. A set of prerequisites for accessing activities was created when teaching the fundamentals of the software engineering course, where students’ progress determines their learning paths. For example, students are encouraged to complete specific learning tasks, such as viewing short videos or completing a quiz, to unlock additional learning resources. This approach was designed to reinforce foundational concepts before students advance, while still offering flexibility in how they engage with content, in alignment with UDL’s emphasis on providing multiple pathways. Figure 4 shows how to build such learning paths to adapt to students’ needs.

Figure 4.

Building adaptive content in Moodle.

Thus, branching scenarios were designed to help students and to achieve inclusion. The analytics and reporting features offered by Moodle were helpful for us. In other words, we carried out manual adaptation. This conditional adaptation is insufficient, though, and we may run into issues when we need to modify the content in real time.

Timed quizzes and deadlines are two further ways that Moodle makes learning accessible. These methods might help students who require more time. Without notifying other students, those students might be granted more time to complete their assignments. In other words, as students require more time to complete activities, face-to-face interactions may lead them to feel neglected; however, blended learning allows for this to happen while protecting students’ privacy.

During the course, the first author identified students who were struggling to complete weekly assignments. Students reported during the focus group sessions that this is due to the required viewing of three separate videos. Based on focus group feedback, we implemented a practical adaptation by providing alternative formats for the video content, including downloadable PDFs with the video transcripts and summarized key points. These materials were distributed to small student groups who reported difficulties with video-based learning. This intervention enabled students to complete the same assignments using different content formats, thereby supporting the UDL principle of “multiple means of representation.” Rather than suggesting a future action, this was an active, iterative modification made during the course based on observed challenges.

Tools that allow students to rewatch recorded videos and review material at their own pace have proven beneficial for supporting diverse learning needs. Such features can be thoughtfully integrated into curricula to promote adaptability and inclusion.

4.3. Inclusivity Through Project-Based Learning in Moodle

In response to the first research question, we clarify here how Moodle was intentionally used to design inclusive and adaptive course content. The course consists of digital materials, including weekly multimedia lectures, structured discussion forums, interactive activities, and conditional quizzes. These were designed based on UDL guidelines to offer multiple means of engagement and representation. For instance, core concepts were delivered through both visual slides and audio narration, while students could choose between video- or reading-based assignments for reflection tasks. The use of conditional release allowed students to receive supplementary resources based on quiz outcomes or forum participation. These design choices were identified by students in their weekly reflections as supportive, especially in terms of flexibility, clarity, and autonomy in navigating the content.

Moodle is found to significantly facilitate and promote inclusivity through project-based learning. It enabled the formation of student groups, the distribution of tasks, the tracking of individual contributions, and the monitoring of group progress. Group assignments supported collaboration and cooperative learning, both of which aligned with the course’s inclusive objectives. Collaborative forums and real-time feedback tools also allowed students with special educational needs, including those with language difficulties or varied learning preferences, to fully participate in coursework and classroom dialogue. Teachers can provide students with customized access to learning materials, where students who require support can benefit and participate in project-based learning.

Moodle allows teachers to monitor students while pairing advanced learners with those who struggle with learning. Furthermore, it facilitates collaboration and continuous assessment. Collaborations improve the participation of such learners who are experiencing difficulties and mitigate the isolation that may arise during face-to-face lectures. Thus, such features help to reduce disengagement and feeling isolated.

Interactive tools such as forums, group workspaces, and interactive quizzes help Moodle support inclusivity through project-based learning, which has the potential to help ensure inclusivity. These elements reflected the UDL principle of providing “multiple means of action and expression,” particularly by encouraging students to complete assignments collaboratively rather than in isolation.

We noticed that some students viewed the assignments during the first two weeks without attempting to finish them. We then established groups to support such students and found that the usage frequency was better. We found that more than 70% of our students access Moodle more than four times a week, which is a good percentage. Thus, providing students with this collaborative workspace helped them to benefit from their peers, which supports UDL’s principle of “multiple means of action and expression”.

4.4. Emotional Inclusion Through Moodle

Moodle provides many features and tools that have the potential to ensure emotional inclusion, which can be considered a key element of inclusive learning. Such features can help in interacting with and engaging those students who feel lonely or disengaged. Building on the UDL-based thematic coding described in Section 3.2.2, we examined how specific emotional inclusion practices—such as encouraging messages, private communication, and peer support—were perceived by students in weekly focus groups. Students consistently highlighted these features as crucial for sustaining motivation, especially those who reported anxiety, difficulty staying on track, or those who hesitate to participate. By aligning student feedback with UDL engagement principles (e.g., offering options for sustaining effort and persistence), we were able to evaluate how emotionally supportive features in Moodle contributed to a more inclusive learning environment. This analysis confirmed that emotional inclusion—often overlooked in RE design—plays a significant role in supporting diverse learners and improving participation and completion rates.

Educator interviews revealed the deliberate use of Moodle features to personalize learning experiences. For example, educators used forum ratings, activity completion tracking, and branching scenarios to guide learners through differentiated paths. These practices were highlighted as aligning with inclusive teaching strategies, enabling varied forms of participation and expression.

Thus, Moodle’s feedback features, such as forums and messaging, may facilitate the emotional inclusion of those struggling students. Through encouragement and a one-to-one setting, which is what these students want, the lecturer’s guidance and support may also help to promote emotional inclusion. Students discussed these features and characteristics in the weekly focus groups, and they reported that the feeling that the lecturer is there is great and supportive even though it is virtual. This promotes their feeling that they are connected and safe, where some students reported that even acknowledging receiving assignments or classwork from the lecturer makes them able to continue. When we discussed the issue of receiving encouragement statements like “well done” and emojis, 83% of the students stated that this boosts their encouragement and gives them motivation to study. They were particularly happy with the capabilities that allow them to communicate with their teachers privately and discuss with them any concerns that they do not want to share with their colleagues. Additionally, the lecturer’s response gives students the impression that they are being watched and tracked. For students who struggle with learning or disengagement, this feeling is crucial since they will experience isolation and a lack of confidence when they are by themselves. This demonstrates how, when utilized effectively by teachers, Moodle’s educational technology can foster emotional inclusion and support real-life interactions.

Furthermore, more interaction and cooperation with other students (peer-to-peer) are also seen as significant emotional inclusion factors. Students reported many benefits and expressed satisfaction with having group assignments and group discussions, which helped them to establish collaborations. Furthermore, educator interviews revealed specific uses of Moodle to support inclusive and adaptive learning strategies. For example, several educators described the use of conditional activities to create multiple learning pathways based on quiz performance. One educator explained, “I set up different resources that become available depending on whether the student completes the first task successfully or not.” Others used group workspaces and forum subscriptions to increase peer interaction and reduce student isolation. Customizing deadlines and access levels was also reported as an important practice to accommodate students with different needs and schedules. These findings illustrate how educators actively used Moodle’s built-in tools to adapt content delivery and foster engagement among a diverse group of learners.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that when used appropriately, Moodle may promote emotional inclusion and engagement in addition to content delivery.

4.5. Performance Trends

Table 3 shows the statistics of the assignments and quiz completion for multiple scenarios.

Table 3.

Statistics of assignments and quiz completion for multiple scenarios.

In Scenario C, flexible deadlines were implemented through Moodle by allowing students to take the quiz at any point within a predefined window (e.g., over three days). However, to maintain academic integrity, each student had a strict time limit once they opened the quiz (e.g., 15 min) and received a randomized set of questions distinct from those of their peers. In contrast, Scenarios A and B involved inflexible quizzes, where all students had to complete the quiz simultaneously at a specific time. The observed increase in completion rate in Scenario C (85%) suggests that the flexibility in quiz timing improved student participation. Importantly, the average performance did not decline compared to the inflexible scenarios, indicating that the flexible approach supported diverse learning needs without compromising assessment standards.

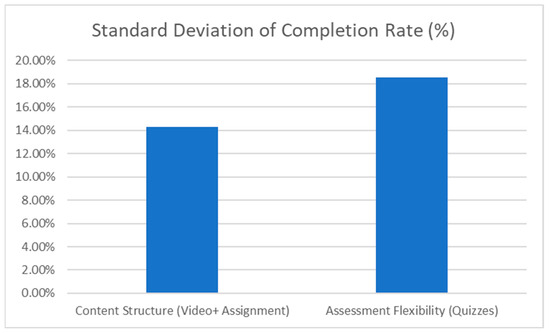

The 15-min video scenario and the flexible timed quizzes achieved the best results, with the highest number of completions (95.7%) and no unresponsive students for the flexible quizzes. The one long video and an assignment had a reasonable performance (71.4%) but were not as effective as the flexible quiz approach; when we examined the standard deviation of completion rates for the two conditions, content structure (i.e., video and assignment formats) recorded a variability of 14.29%, while assessment flexibility (strict vs. flexible quizzes) showed a higher variability of 18.57%, as shown in Figure 5. While we use these values illustratively to reflect differences in consistency of student engagement across scenarios, we acknowledge that standard deviation alone does not provide sufficient statistical evidence to claim significance. However, these results suggest that students responded more sensitively to how quizzes were structured than to the content format. According to student feedback, this may be due to quiz grades carrying higher weight than assignments, as well as the timing flexibility reducing pressure and improving engagement. Further studies with formal statistical testing are needed to substantiate this preliminary insight. According to our discussions with students, this was because the mark’s weight for the quizzes is more than the weight for the assignments. The three short videos and an assignment scenario recorded the highest number of students who did not complete the process. Students reported that this was because of a higher perceived workload.

Figure 5.

Standard deviation of completion rates for content structure and assignment flexibility.

The strictly timed quizzes had a critical drop in engagement, recording a noticeable number of students who did not respond at all. This means that flexible deadlines appear to not only increase completion rates but also provide more consistent engagement across different students. This highlights the importance of building adaptive assessment mechanisms—such as flexible deadlines—that accommodate diverse student needs. In our case, offering flexible quiz deadlines helped reduce barriers for learners experiencing time-related or cognitive challenges, and it was associated with improved completion rates and engagement. This aligns with inclusive design principles in blended learning.

4.6. Challenges

4.6.1. Content-Related Challenges

The difficulty in handling multiple video materials assigned for a single task was a main challenge that was identified from students’ feedback. A total of 57% of students felt overwhelmed when they had to watch many video lectures to complete one assignment. This confused them and hurt their time management. This challenge increases when the videos differ in format or teaching methodologies. There is a heavy cognitive load associated with navigating and integrating information from several sources within a short period, which makes maintaining focus or perceiving new concepts more difficult for students. Our results highlight the need for a more effective approach to content delivery, where each assignment is linked to specific, concise resources.

4.6.2. Accessibility-Related Challenges

Accessibility-related challenges are another issue that students face. Such challenges affect their capacity to fully engage with the learning process. The strict quiz schedules were one of the main concerns the students talked about. Personal obligations or time conflicts did not enable students to attend such strict quizzes, particularly in a blended learning environment where asynchronous participation is often necessary. Some students mentioned that missing deadlines was not due to a lack of motivation but rather a mismatch between course timelines and their availability. These challenges highlight the significance of integrating more adaptive timing mechanisms and offering alternatives for assessments to achieve an inclusive and flexible learning environment. This framework, which was developed as a result of our analysis, helps illustrate how inclusive and adaptive teaching practices emerged through Moodle-supported course design.

5. Discussion

This section discusses the results of our study and answers the research questions. Furthermore, it maps these answers to the inclusive learning framework. We built our discussion on the results from student feedback, classroom observations, and the interviews that we conducted with educators. We interpreted these results to provide insights on how Moodle’s features and design practices can influence inclusive and adaptive learning. We organized these insights to answer the research questions, and they were mapped to the inclusive and adaptive frameworks’ principles.

5.1. How Can Moodle Be Used to Support Inclusive and Accessible Learning Experiences for Students with Diverse Needs and Challenges in Blended Learning Environments?

We identified that having multiple files for multimodal content and frequent submissions might discourage students and make it more difficult for them to manage many tasks at once, which lowers their ability to concentrate on learning new information or improving their skills. This conclusion was based on student interactions and the authors’ experience. This finding suggests, furthermore, that students who struggled with delayed learning felt more relaxed with timed quizzes that had flexible due dates rather than strict ones. Many students stated that flexible quiz deadlines decreased stress and enabled them to adequately study and prepare, which improved their performance. This aligns with the UDL principle of having “multiple means of engagement”. The emotional inclusion and students’ feeling that they are safe play an important role in promoting students’ motivation. It is clear that the flexible times for quizzes helped students to conduct and submit their quizzes without fear, which improves their academic performance. Though online flexibility can support learners and allow them to engage with content at their own pace, it is important to consider that students with learning difficulties may also require more direct and structured guidance. Our blended learning model ensures that these students benefit from both the autonomy of online materials and the personalized support of face-to-face sessions. Although the asynchronous elements (e.g., videos, Moodle activities) provide flexibility, they are complemented by synchronous lectures and interactive in-person activities that foster emotional support, real-time feedback, and peer collaboration. Therefore, our model avoids the limitations of a predominantly online environment and instead promotes a hybrid approach, which has been proven effective in maintaining accessibility, reducing stress, and enhancing engagement for students with learning difficulties. The first author, who is the lecturer, noted this reduction in missed responses after introducing flexibility in deadlines.

Moreover, our results ensured the importance of delivering multi-modal content, which is considered one of the main principles of our inclusive learning framework. A number of the students who participated in this study talked about the importance of having explanations for the videos to simplify the process of following complex topics in the course, such as the “software architecture” chapter. The authors of [61] emphasized the importance of having new methods for teaching subjects related to software architecture because the traditional lecture method used to teach software architecture in the classroom is not sufficient to provide students with the necessary practical experience to pursue a career as software architects in the future. Therefore, having multimodal content that students can explore on their own time is beneficial. Students emphasized the importance of pausing and replaying the videos in understanding complex topics. This aligns with our framework’s “multimodal content to support different learning styles” principle. This principle assures the importance of providing visual content that fits different learning styles instead of only having lecture slides.

While our work focuses on inclusive content design and pedagogical adaptability, other studies, such as [43], have advanced Moodle’s personalization capabilities by modeling learners’ personalities through unobtrusive learning analytics. Such complementary approaches highlight the growing potential of Moodle to support both inclusive instruction and personalized learning pathways in diverse educational settings.

Our study expands previous studies by focusing on university students in a blended learning environment, applying inclusive pedagogical strategies grounded in the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework.

Furthermore, unlike previous studies that focus on usability evaluations, such as the work by [46], which focused on assessing how students with disabilities interact with Moodle, we move beyond interface-level accessibility and address instructional design. Our study introduces a framework for developing inclusive and adaptive content. Thus, our approach is not limited to evaluating user experience but instead emphasizes how course content itself can be designed to accommodate diverse learner needs, foster engagement, and improve learning outcomes in a blended learning context. This distinction is critical in regions like Jordan, where the use of LMSs and blended learning are expanding fast but pedagogical adaptation for diverse learners remains underdeveloped.

Thus, our results contribute to understanding the characteristics of a blended learning course that help to achieve inclusion. Students’ behavior helped us to provide recommendations on how to design a blended learning course that can guarantee inclusion. Feedback from both students and educators highlights the importance of well-designed content and multimodal content, which directly maps to our framework.

5.2. What Are the Available Features in Moodle That Can Promote Inclusive and Adaptive Blended Learning?

To answer this question, we first looked at the literature on Moodle’s current features that might support inclusive and adaptable learning. Additionally, the first author investigated how Moodle may support inclusive and adaptable blended learning. She made an effort to use Moodle for inclusive learning in an efficient manner. Lastly, interviews with educators were conducted to find out how they utilize Moodle to achieve inclusive and adaptive learning and how experienced they are in both inclusive learning and in using Moodle’s features.

Our findings reveal that Moodle promotes inclusive education by making resources like screen readers and translation plugins available to students with impairments. Conditional activities, which guarantee that students receive information appropriate to their needs, also encourage adaptive learning. In addition, educators can gain insight into how students behave, which might help in tailoring the material to meet their requirements. The analytical tools available may be utilized to do this.

5.3. How Is the Role of Moodle in Inclusive Blended Learning Perceived by Educators in Jordanian Higher Education Institutions?

Among the educators interviewed, 31% acknowledged Moodle’s flexibility in allowing them to create courses that are tailored to the requirements of their students and to personalize the material. When those instructors found that Moodle offers an inclusive and adaptable environment, the capabilities that support adaptive learning were beneficial. Additionally, 88% of respondents valued Moodle’s capacity to offer information in both Arabic and English. Additionally, 50% of educators agreed that having both synchronous and asynchronous learning options was important. They suggested a variety of resources, including forums, assignments, and tests.

Nearly all teachers expressed dissatisfaction about the inadequate instruction on how to use Moodle for inclusive blended learning. They stated that while they have no problem utilizing the basic capabilities, they find it difficult to use the advanced ones.

5.4. What Are the Challenges in Investing in Moodle for Achieving Inclusive Education, and How to Deal with Such Challenges?

Although Moodle facilitates inclusive and adaptable learning, the use of these resources in the classroom is dependent on the expertise and training of the educators. Additionally, in remote locations with limited infrastructure, students are unable to take advantage of the well-designed information due to inconsistent Internet access.

Although Moodle is free and open-source, hosting, customization, and staff training are expensive aspects of its deployment and maintenance. Institutions of higher education must employ staff who will customize Moodle and provide several workshops to train educators.

Moodle might not be able to meet the accessibility needs of certain students with severe impairments unless specific settings are made. Accessible technologies from third parties may be integrated within Moodle.

To mitigate learning fatigue, educators should ensure that the learning materials they post do not impose a significant mental workload. This result is consistent with the results of [62], who focused on the importance of developing learning material that does not need a high cognitive load as determined by cognitive load theory [63,64], which ensures the importance of addressing limited cognitive processing abilities when designing instructional material.

Another major problem we found is that teachers could be unwilling to utilize Moodle and to switch from traditional to Moodle-based teaching. To overcome these obstacles, institutions might concentrate on trial projects that use blended learning to teach certain modules and demonstrate the outcomes. Higher education institutions should also take into account the workload of teachers, avoiding assigning them too many courses that they are unable to handle.

Finally, our framework is designed to evaluate the inclusive and adaptive capabilities of Moodle. However, many of the key design elements we explored—such as adaptive content pathways, multimedia integration, and collaborative assignments—are not exclusive to Moodle. Similar functions exist in other learning management systems (LMSs), including Canvas and Blackboard. Therefore, while there might be various workflows, we believe that the inclusive and adaptive strategies discussed in this study can inform course design across different platforms. Future studies could investigate the application and comparative effectiveness of such practices in diverse LMS environments.

6. Conclusions, Recommendations, and Future Work

We explored how Moodle, as a widely adopted LMS, can be utilized to deliver inclusive and adaptive content in blended learning environments. We built our research on classroom experiences, focus group discussions, and educator interviews. Furthermore, we identified many barriers that hinder inclusive practices, such as the lack of educator training, the cognitive overload caused by poorly structured content, and the underutilization of Moodle’s adaptive features.

To deal with these challenges, we developed and applied a practical framework for designing inclusive and adaptive content. Our framework aligns with the principles of UDL and emphasizes clarity of learning objectives, ensures the importance of multimodal content delivery, and builds flexible assessments.

Our results demonstrate that if educators receive the necessary support and employ Moodle’s conditional activities, branching scenarios, and collaborative tools, students with diverse learning needs can be better supported.

Practical insights include the following:

Universities should have structured training programs for educators on how to design inclusive and adaptive content within existing LMS platforms.

Course designers should minimize cognitive load by using concise multimedia and offering alternative formats for essential content to meet different students’ needs.

Adaptive learning paths and conditional access features in Moodle can be utilized to personalize the learning experience.

Regular feedback loops, such as weekly focus groups, can inform iterative improvements to course design and delivery. Through utilizing the resources offered by Moodle, educators may be properly trained by their institutions to provide inclusive and adaptable blended learning.

As universities increasingly adopt blended learning models, we highly recommend that they integrate design principles for inclusive and adaptive blended learning in their programs. Applying the proposed framework to evaluate the capabilities of LMSs for inclusion might be helpful and may provide structural pathways. Moreover, we think that universities should ensure the training of educators on achieving inclusivity in education and on inclusivity features in LMSs.

7. Limitations and Future Work

Our study follows a descriptive exploratory empirical approach utilizing qualitative data from a single course experience at one university. This provided deep, rich, and real practice insights; however, it also limits the generalizability of our findings because it does not fully represent the Jordanian or international higher education settings. Instructional factors in other settings might have an impact on the results. Therefore, in future research, we need to adopt a mixed-method research design that combines quantitative and qualitative data to conduct a cross-institutional comparative study to generalize our results and to ensure their validity in other contexts. Future studies could benefit from utilizing the framework to evaluate Moodle in other academic disciplines and other universities to evaluate its applicability in diverse blended learning environments. It can also be used to evaluate the capacity of other LMSs (such as Blackboard, Google Classroom, and Canvas) to provide inclusive and adaptable material, as well as to conduct additional analysis of the findings. Furthermore, the course’s flipped blended structure emphasized in-person lectures while delivering core material and assessments online. As such, results may be less generalizable to fully online or more equally distributed blended models.

Future research should also focus on the use of AI tools that have the potential to enhance inclusion and adaptability by including AI-driven content. In other words, future work should be focused on developing machine learning-based systems that can respond to students’ behavior and suggest tasks according to students’ real-time performance. To conclude, we look to strengthen the validity of our framework in different blended learning contexts through future, deeper empirical testing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.A.-Q. and J.T.N.; methodology, L.F.A.-Q.; validation, L.F.A.-Q., J.T.N. (overall validation), and F.M.A. (interview data validation); analysis, L.F.A.-Q.; data curation, L.F.A.-Q. (primary data collection and weekly student focus groups) and F.M.A. (interview data); writing—original draft preparation, L.F.A.-Q.; writing—review and editing, L.F.A.-Q. and J.T.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Scientific Research Committee, Philadelphia University, on 3 November 2024. The approval ID is QFO-SR-DR-033.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all students and educators who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Interview Questions and Their Rationale

The questions asked during the interviews and the reasons why we asked them are as follows.

| No | Question | Rationale |

| 1 | From your experience, what does inclusive blended learning mean? And how do you define its key principles in higher education? | The first question is designed to see the level of understanding of inclusive blended learning among the participants |

| 2 | What specific tools or features in Moo-dle have you used (or are aware of) that support adaptive and inclusive learning for students with diverse learning needs? | The second question is designed to find out the level of familiarity with Moodle’s inclusive features |