The Relative Popularity of Video Game Genres in the Scientific Literature: A Bibliographic Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

- [RQ1] What is the distribution of research papers with regard to the video game genres they refer to, and how does it relate to the number of games developed in the respective genres?

- [RQ2] How has the quantity of research papers referring to video game genres evolved over time, and what are the differences among the respective genres?

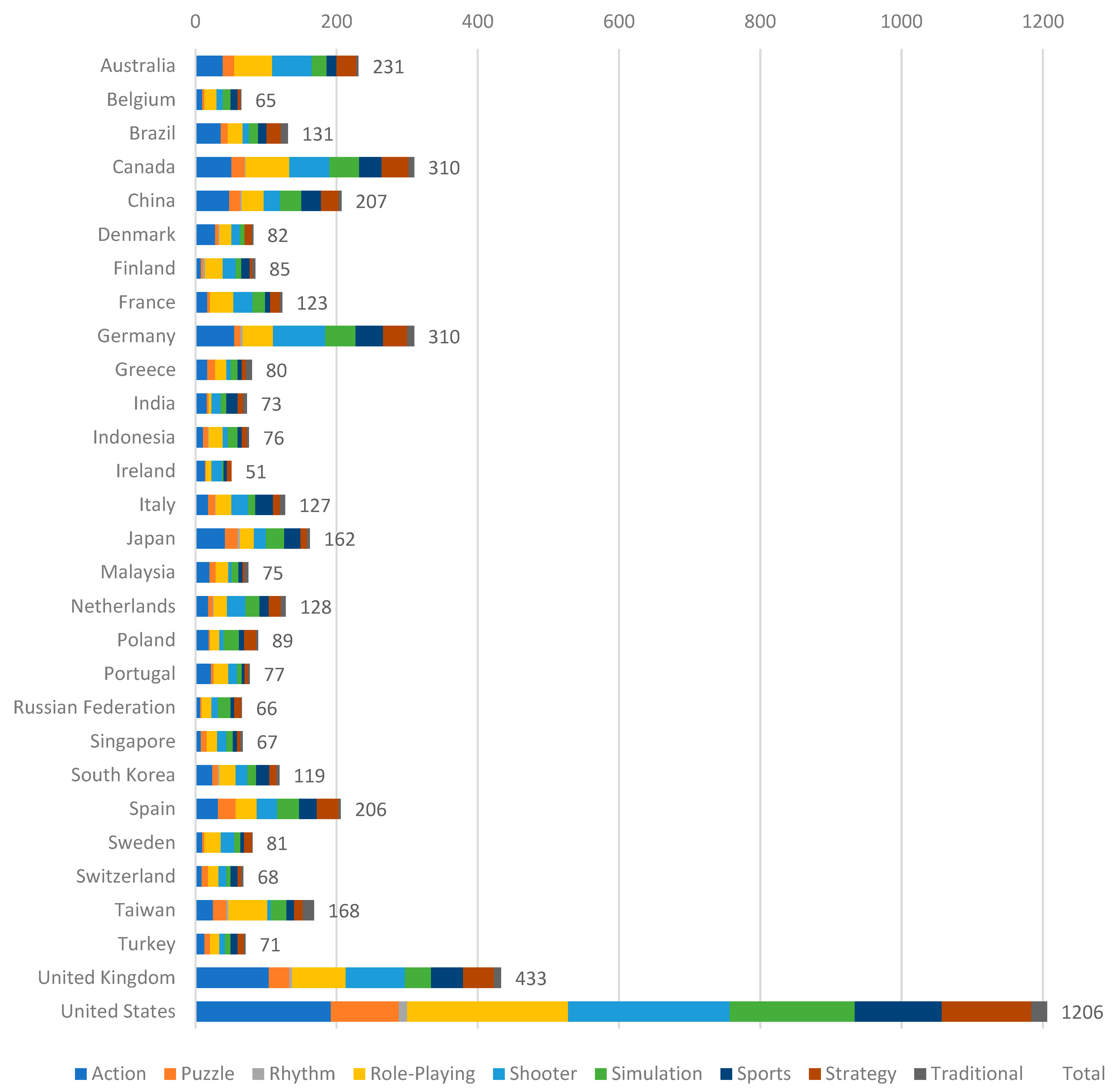

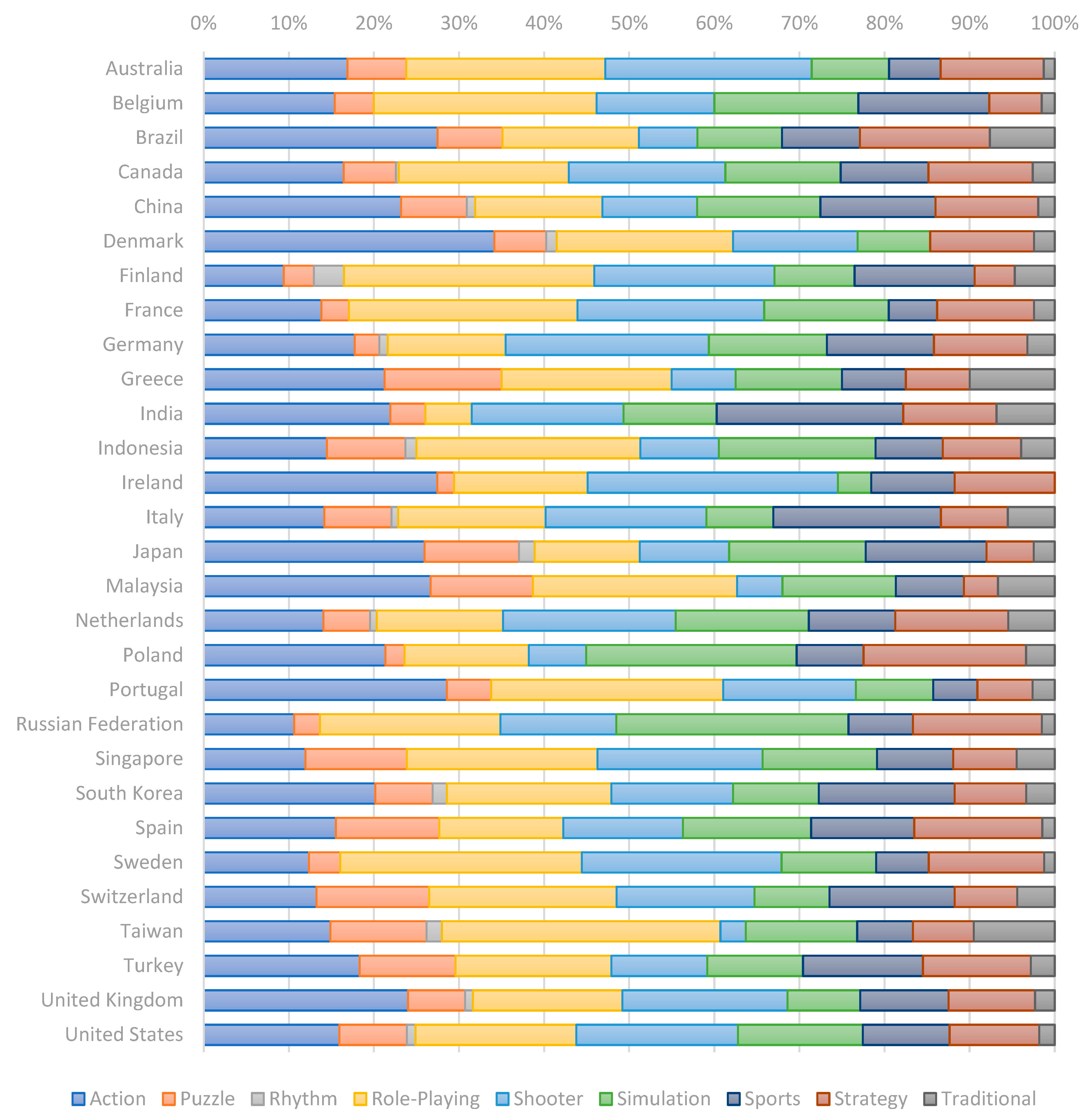

- [RQ3] With which countries are the majority of the authors of the research papers referring to video game genres affiliated, and how does their share of research in this vein compare to the general scientific publication output in these countries?

- [RQ4] What are the most impactful research papers referring to video game genres, and what topics they are on?

2. Classifications of Video Games

2.1. Classic Taxonomies

- Skill-and-action games, which are characterized by real-time play, a heavy emphasis on graphics and sound, and demanding of the player mainly hand–eye coordination and a fast reaction time;

- Strategy games, which emphasize cogitation rather than manipulation, do not put emphasis on motor skills, and typically require more time to play than skill-and-action games.

2.2. Survey-Data-Based Taxonomies

- Mini-games, in which players are challenged by obstacles and time pressure;

- Action, in which players are challenged by opponents and time pressure;

- Adventure, in which the challenges take the form of a puzzle and/or search;

- Role-play, in which players are challenged by opponents and limited resources but may also have to search;

- Resource, in which players are challenged by opponents and limited resources and, to a lesser extent, opponents and time pressure.

2.3. Multi-Aspect Taxonomies

- Competitive (involving opponents) vs. noncompetitive (not involving opponents);

- Interactive (involving game participants who serve to present obstacles to be overcome by an opponent, all in pursuit of the same goal) vs. noninteractive (not having this feature) (note that a game must be competitive in order to also be interactive, but not all competitive games are interactive);

- Physical (requiring participants to pursue the game goal through the use of their motor skills) vs. nonphysical (not having this feature).

- Physical—the game’s physical basis;

- Structural—capturing several formal, abstract aspects of games;

- Communicational—which concerns communication with the player;

- Mental—which concerns the perception of the game as played by an agent.

2.4. Vendors’ Classifications

2.5. Specialized Classifications

- Application area, e.g., education, well-being, or training;

- Activity, which refers to the character of the player’s activity in a game (e.g., physical exertion, psychological, and mental);

- Modality, which describes the channel by which information is sent from the computer to the player (e.g., visual, auditory, haptic, smell, and others);

- Interaction style, which defines whether the interaction between the player and the game is carried out using, e.g., a keyboard or mouse, a brain interface, or eye-gaze movement tracking;

- Environment, which includes social presence, mixed reality, virtual environment, 2D/3D, local awareness, mobility, and online.

- Gameplay, which provides information about how a game is played;

- Purpose, which refers to the designed purpose of a game apart from entertainment;

- Scope, which refers to the target of a game (e.g., the market, the audience, etc.).

- Micromanagement games, which involve multiple resources that the player uses to build an internal economy;

- Single-resource games, in which the player can only produce one resource and spend it to complete upgrades in order to progress in the game;

- Derivative games, which involve single or multiple resources with which the player can build resource generators to automate the production of the main resource of the game;

- Multi-player incremental games, which allow multiple players to accumulate resources simultaneously, and the accumulated resources are shared.

- Clicker games, which involve clicking, rubbing, or tapping as their core mechanic, with damage caused and/or resources generated by repeating clicking cycles, separated by waiting periods;

- Minimalist games, which reduce the number of available actions to a small subset of options, either through game mechanics that automate gameplay or gameplay phases that reduce player interaction;

- Zero-player games, which require no player involvement after starting or allow limited input during setup but no influence on gameplay. These include

- ○

- Setup-only games, which allow the player to interact with the game only once at the start of the game, and then the game plays itself without further involvement from the player;

- ○

- AI play, in which all progress in the game is controlled solely by the game’s AI.

2.6. Comparison of Classifications

3. Materials and Methods

- Hughes provided an annotated bibliography of the major journals publishing video game scholarship [38];

- Frome and Martin analyzed over 580 articles from two relevant journals to identify the canon of the most-frequently cited games in game scholarship, explicating different functions of game citation, providing an empirical basis for identifying under-researched games and identifying the games with which familiarity is most important in order to understand the existing research [39].

- García-Sánchez et al. analyzed 7133 articles from the 2013–2018 period indexed by Dimensions.ai to identify the change in the number of video game papers published yearly; the authors, universities, and countries most involved in this area of research; the journals most often serving as the publication venues; and the number of video-game papers and citations belonging to different fields of research [40].

- Yoon performed bibliographic coupling, co-citation analysis, and visualization of bibliometric networks using data obtained from Web of Science to map and explore the current state of research on advertising in digital games [41].

- Núñez-Pacheco and Penix-Tadsen presented a bibliographical review of several theoretical trajectories in game studies, concluding that as game studies have evolved as a discipline, the initial theoretical debates on narratology and ludology have undergone profound transformations, bringing depth to the analysis of games’ meanings, and diversified the tools and techniques for analyzing games as digital and cultural artefacts [42].

- Montes Buendia et al. analyzed 30 papers on narrative in video games published between the years 2012 and 2022 and indexed in Scopus, ProQuest, Ebsco, or Science Direct, presenting the number of relevant papers published per year, country with which the authors are affiliated, language, publication license (open or not), and sex of the authors [43].

- Damaševičius et al. used the Scopus database to perform a systematic meta-review of 53 survey papers on the application of serious games and gamification in healthcare, assessing the present status of this vein of research and identifying its challenges and future trends [44].

- Eckert et al. examined 77 publications regarding dementia and video games published from 2004 to 2023 and indexed in PubMed to assess developments and trends in video game technology applicable to dementia care and detection, considering bibliographic, medical, and technical variables [45].

- Nguyen et al. systematically reviewed 1152 Scopus-indexed documents on role-playing games from the 1986 to 2023 period, providing insights into growth patterns, global interest, and influential contributors [46].

(TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Video game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Videogame”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Digital game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Computer game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Console game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Mobile game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Internet game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Web game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Interactive game”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Action game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Action-Adventure”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Arcade game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Block Breaking”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Brawler game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Fighting game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Hack and Slash”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Multiplayer Online Battle Arena”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Music game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Party game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Platform game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Stealth game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Survival game”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Vehicle Combat”)) AND PUBYEAR > 1980 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“ch”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“cp”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“bk”))

4. Results

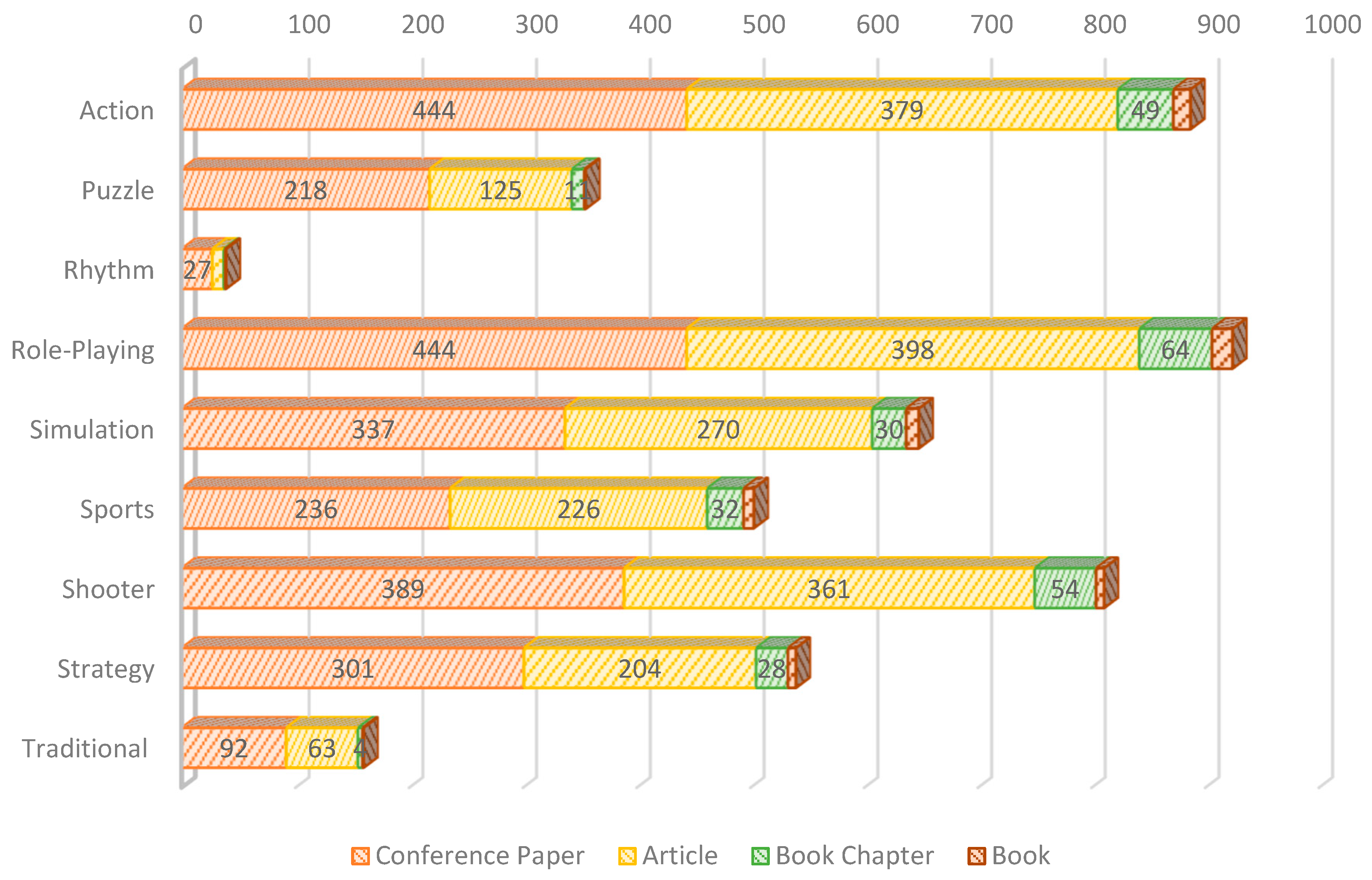

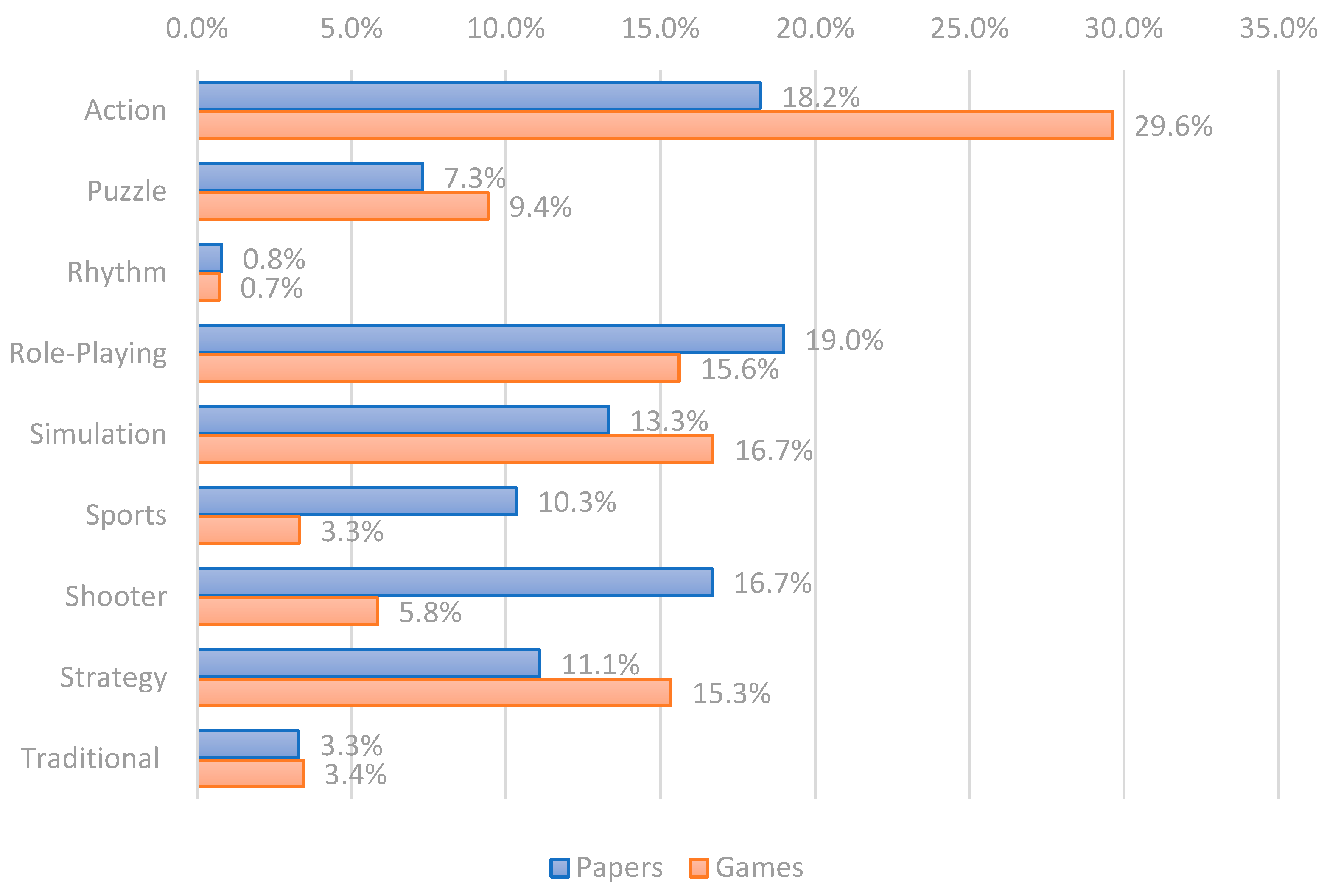

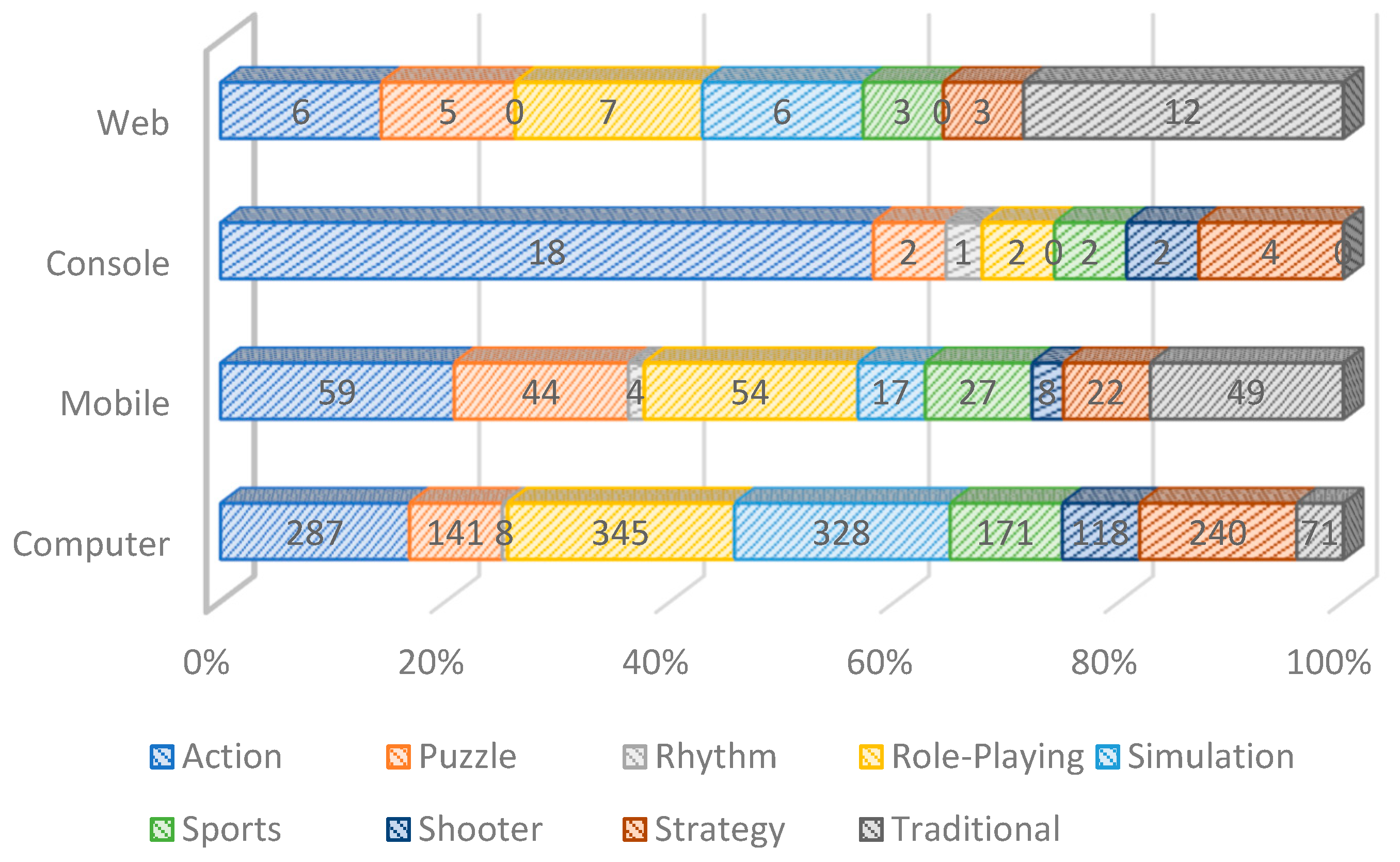

4.1. Genre Popularity Comparison

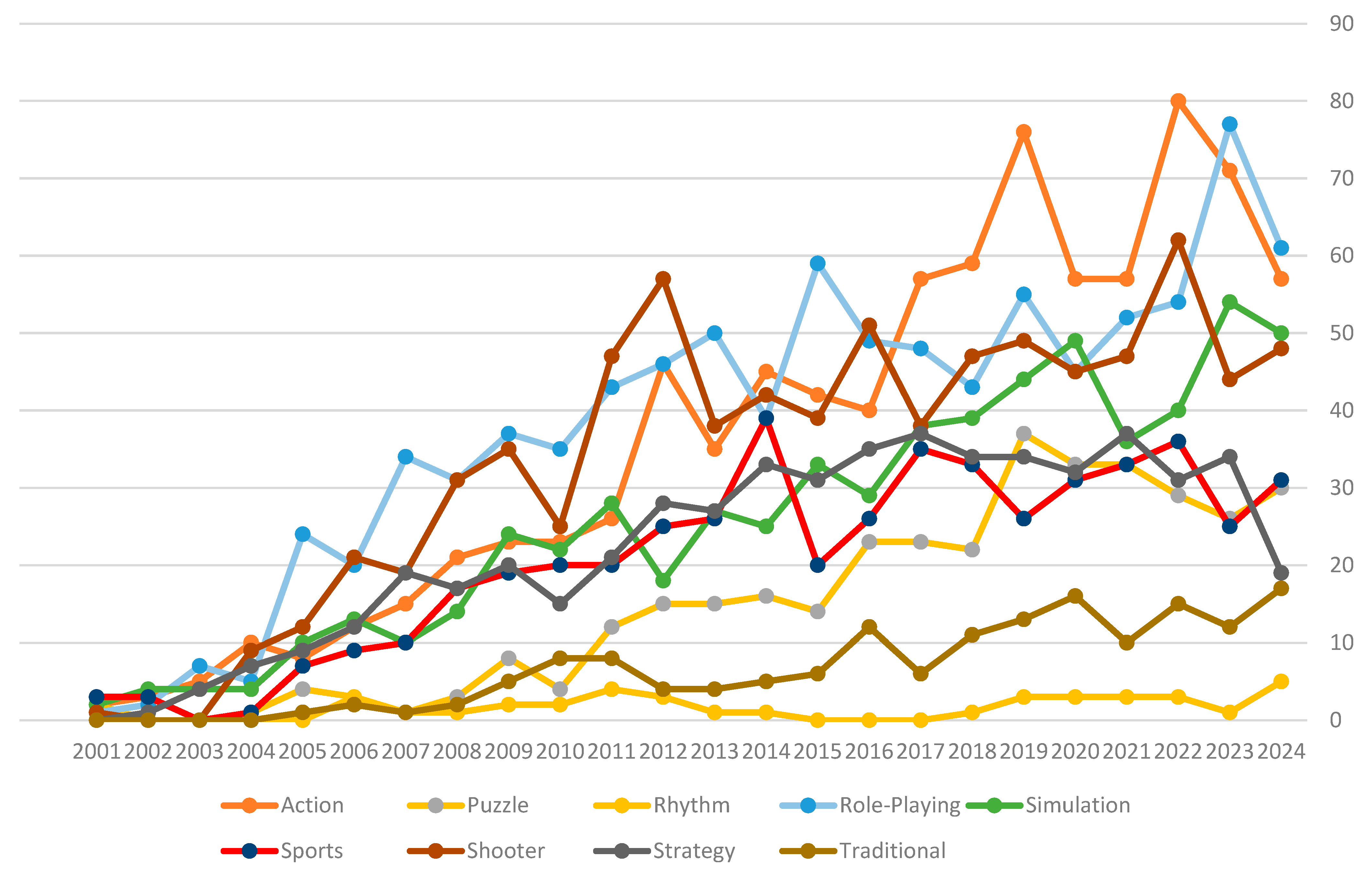

4.2. Evolution of Popularity over Time

- One genre (Rhythm games) that attracted only scarce interest from researchers during the entire period under analysis, achieving a maximum of five publications only in the last wholly covered year (2024);

- One genre (Traditional games) growing (with occasional humps and bumps) with a relatively slow speed, reaching its peak level of 17 publications in 2024;

- Two genres that achieved their peak or near-peak levels early (the research popularity of which has more or less stabilized since then): Sports games, with their peak number of publications, 39, reached in 2014, and Shooter games, with 57 publications in 2012 (second only to 62 publications in 2022);

- Two genres for which research interest seems to have waned in recent years: Strategy games, with 19 publications in 2024 vs. 37 in 2017 and 2021, and Puzzle games, with 30 publications in 2024 vs. 37 in 2019;

- Two genres that attracted the most attention in recent years bur for which attention has decreased last year: Role-Playing games, falling to 61 publications in 2024 from their peak of 77 publications one year earlier, and Action games, falling to 57 publications in 2024 from their peak of 80 publications two years earlier.

4.3. Research Location and Genre Popularity

4.4. Comparing the Impacts of Research on the Respective Genres

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juul, J. The Game, the Player, the World: Looking for a Heart of Gameness. PLURAIS-Rev. Multidiscip. 2010, 1, 248–270. [Google Scholar]

- Bergonse, R. Fifty Years on, What Exactly Is a Videogame? An Essentialistic Definitional Approach. Comput. Games J. 2017, 6, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokošnỳ, I. Digital Games as a Cultural Phenomenon: A Brief History and Current State. Acta Ludologica 2018, 1, 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Santasärkkä, S. The Digital Games Industry and Its Direct and Indirect Impact on the Economy. Case Study: Supercell and Finland. Bachelor’s Thesis, Metropolia University of Applied Sciences, Helsinki, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, E.A.; Connolly, T.M.; Hainey, T.; Boyle, J.M. Engagement in Digital Entertainment Games: A Systematic Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E.A.; Hainey, T.; Connolly, T.M.; Gray, G.; Earp, J.; Ott, M.; Lim, T.; Ninaus, M.; Ribeiro, C.; Pereira, J. An Update to the Systematic Literature Review of Empirical Evidence of the Impacts and Outcomes of Computer Games and Serious Games. Comput. Educ. 2016, 94, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, I.; Shimul, A.S.; Phau, I. Motivations of Playing Digital Games: A Review and Research Agenda. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekler, E.D.; Bopp, J.A.; Tuch, A.N.; Opwis, K. A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies on the Enjoyment of Digital Entertainment Games. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 927–936. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D.B.; Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Killingsworth, S.S. Digital Games, Design, and Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, M.J.P. Genre and the Video Game. In The Medium of the Video Game; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2002; pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, C.A. Game Taxonomies: A High Level Framework for Game Analysis and Design. Gamasutra 2003, 3. Available online: https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/game-taxonomies-a-high-level-framework-for-game-analysis-and-design (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Starosta, J.; Kiszka, P.; Szyszka, P.D.; Starzec, S.; Strojny, P. The Tangled Ways to Classify Games: A Systematic Review of How Games Are Classified in Psychological Research. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.I.; Lee, J.H.; Clark, N. Why Video Game Genres Fail: A Classificatory Analysis. Games Cult. 2017, 12, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Most Popular Video Game Genres Among Internet Users Worldwide as of 3rd Quarter 2024, by Age Group. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1263585/top-video-game-genres-worldwide-by-age/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Steam Charts. An Ongoing Analysis of Steam’s Concurrent Players. Available online: https://steamcharts.com (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Zukowski, C. More Evidence of Which Genres Steam Shoppers Love to Play. Available online: https://howtomarketagame.com/2022/05/30/more-evidence-of-which-genres-steam-shoppers-love-to-play/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Berg, H.A. The Computer Game Industry. Master Thesis, Norges Teknisk-Naturvitenskapelige Universitet, Trondheim, Norway. Available online: https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/handle/11250/262074 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Cunha, L.R.; Pessa, A.A.B.; Mendes, R.S. Shape Patterns in Popularity Series of Video Games. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 185, 115081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.P. The (Computer) Games People Play: An Overview of Popular Game Content. In Playing Video Games; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, C. The Art of Computer Game Design; Osborne/McGraw-Hill: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Heintz, S.; Law, E.L.-C. Game Elements-Attributes Model: A First Step towards a Structured Comparison of Educational Games. In Proceedings of the 2015 DiGRA International Conference, Lüneburg, Germany, 14–17 May 2015; Digital Games Research Association: Lüneburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heintz, S.; Law, E.L.-C. The Game Genre Map: A Revised Game Classification. In Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, London, UK, 5–7 October 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Gose, E.; Menchaca, M. Video Game Genres and What is Learned From Them. In Proceedings of the World Conference on E-Learning, New Orleans, LA, USA, 27–30 October 2014; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE): New Orleans, LA, USA, 2014; pp. 673–679. [Google Scholar]

- Apperley, T.H. Genre and Game Studies: Toward a Critical Approach to Video Game Genres. Simul. Gaming 2006, 37, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarseth, E.; Smedstad, S.M.; Sunnanå, L. A Multidimensional Typology of Games. In Proceedings of the DiGRA Conference, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 6 November 2003; University of Utrecht: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Elverdam, C.; Aarseth, E. Game Classification and Game Design: Construction Through Critical Analysis. Games Cult. 2007, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossen, D.P. The Nature and Classification of Games. Avante 2004, 10, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Aarseth, E.; Grabarczyk, P. An Ontological Meta-Model for Game Research. In Proceedings of the 2019 DiGRA International Conference: Game, Play and the Emerging Ludo-Mix, Kyoto, Japan, 6–10 August 2019; Digital Games Research Association: Turin, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Karlova, N.; Clarke, R.I.; Thornton, K.; Perti, A. Facet Analysis of Video Game Genres. In IConference 2014 Proceedings; Humboldt-Universität: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Schmalz, M.; Newman, M.; Koughan, L.D. UW/SIMM Video Game Metadata Schema: Controlled Vocabulary for Genre. Version 1.3. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/uwgamergroup/vocabulary-gameplay-genre/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Google Play Store Categories. Available online: https://developers.apptweak.com/reference/google-play-store-categories (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- App Store Genres. Available online: https://42matters.com/docs/app-market-data/ios/apps/appstore-genres (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- All Steam Game Tags. Available online: https://steamdb.info/tags (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Laamarti, F.; Eid, M.; El Saddik, A. An Overview of Serious Games. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2014, 2014, 358152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaouti, D.; Alvarez, J.; Jessel, J.-P. Classifying Serious Games: The G/P/S Model. In Handbook of Research on Improving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 118–136. [Google Scholar]

- Alharthi, S.A.; Alsaedi, O.; Toups Dugas, P.O.; Tanenbaum, T.J.; Hammer, J. Playing to Wait: A Taxonomy of Idle Games. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; ACM: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Passas, I. Bibliometric Analysis: The Main Steps. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.J. Fetch Quest: A Select Bibliography of Game Studies Journals. Ser. Libr. 2017, 73, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frome, J.; Martin, P. Describing the Game Studies Canon: A Game Citation Analysis. In Proceedings of the DiGRA 2019 Conference: Game, Play and the Emerging Ludo-Mix, Kyoto, Japan, 6–10 August 2019; Digital Games Research Association/Ritsumeikan University: Kyoto, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, P.; Mora, A.M.; Castillo, P.A.; Pérez, I.J. A Bibliometric Study of the Research Area of Videogames Using Dimensions.ai Database. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 162, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, G. Advertising in Digital Games: A Bibliometric Review. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Pacheco, R.; Penix-Tadsen, P. Divergent Theoretical Trajectories in Game Studies: A Bibliographical Review. Artnodes Rev. Arte Cienc. Tecnol. 2021, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes Buendia, V.A.A.; Jácobo Morales, D.; Gonzales Medina, M.A. The Audiovisual Narrative in Videogames. A Systematic Review of Literature between 2012 and 2022. In Proceedings of the 21th LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology (LACCEI 2023), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 19–21 July 2023; LACCEI: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Damaševičius, R.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Blažauskas, T. Serious Games and Gamification in Healthcare: A Meta-Review. Information 2023, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, M.; Ostermann, T.; Ehlers, J.P.; Hohenberg, G. Dementia and Video Games: Systematic and Bibliographic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Pham, H.-H.; May, A.Y.C.; Chin, T.L. Exploring the Landscape of Role-Playing Game Research Through Bibliometric Analysis From 1986 to 2023 Using Scopus Database. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2025, 1, 2315333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setya Murti, H.A.; Dicky Hastjarjo, T.; Ferdiana, R. Platform and Genre Identification for Designing Serious Games. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 30–31 July 2019; IEEE: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Hu, H.; Soares, M.M. Usability Assessment of Nintendo Switch. In Design, User Experience, and Usability; Marcus, A., Rosenzweig, E., Soares, M.M., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 369–385. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, C.-C.; Wu, C.-F. Display and Device Size Effects on the Usability of Mini-Notebooks (Netbooks)/Ultraportables as Small Form-Factor Mobile PCs. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Galeote, D.; Hamari, J. Game-Based Climate Change Engagement: Analyzing the Potential of Entertainment and Serious Games. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-H.; Shen, K.-S.; Ma, M.-Y. The Functional and Usable Appeal of Facebook SNS Games. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromme, J. Computer Games as a Part of Children’s Culture. Game Stud. 2003, 3, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Spence, I.; Pratt, J. Playing an Action Video Game Reduces Gender Differences in Spatial Cognition. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, I.; Feng, J. Video Games and Spatial Cognition. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2010, 14, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, M.W.G.; Green, C.S.; Bavelier, D. The Development of Attention Skills in Action Video Game Players. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 1780–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, W.R.; Kramer, A.F.; Simons, D.J.; Fabiani, M.; Gratton, G. The Effects of Video Game Playing on Attention, Memory, and Executive Control. Acta Psychol. 2008, 129, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oei, A.C.; Patterson, M.D. Enhancing Cognition with Video Games: A Multiple Game Training Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strobach, T.; Frensch, P.A.; Schubert, T. Video Game Practice Optimizes Executive Control Skills in Dual-Task and Task Switching Situations. Acta Psychol. 2012, 140, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Folmer, E. Blind Hero: Enabling Guitar Hero for the Visually Impaired; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Höysniemi, J. International Survey on the Dance Dance Revolution Game. Comput. Entertain. 2006, 4, 8-es. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichlmair, M.; Kayali, F. Levels of Sound: On the Principles of Interactivity in Music Video Games. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference of the Digital Games Research Association DiGRA, Tokyo, Japan, 24–28 September 2007; pp. 424–430. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, H.; Griffiths, M.D. Social Interactions in Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Gamers. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.-J.; Yang, L.-H.; Wang, S.-Y. A Concept Map-Embedded Educational Computer Game for Improving Students’ Learning Performance in Natural Science Courses. Comput. Educ. 2013, 69, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzoni, R.A.; Brunborg, G.S.; Molde, H.; Myrseth, H.; Skouverøe, K.J.M.; Hetland, J.; Pallesen, S. Problematic Video Game Use: Estimated Prevalence and Associations with Mental and Physical Health. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garris, R.; Ahlers, R.; Driskell, J.E. Games, Motivation, and Learning: A Research and Practice Model. Simul. Gaming 2002, 33, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopher, D.; Weil, M.; Bareket, T. Transfer of Skill from a Computer Game Trainer to Flight. Hum. Factors 1994, 36, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhi, A.; Rayati, M.; Bahrami, S.; Ranjbar, A.M. Integrated Demand Side Management Game in Smart Energy Hubs. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 6, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, J.E.; Borbely, M.; Filler, J.; Huhn, K.; Guarrera-Bowlby, P. Use of a Low-Cost, Commercially Available Gaming Console (Wii) for Rehabilitation of an Adolescent with Cerebral Palsy. Phys. Ther. 2008, 88, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labbe, M.; Michaud, F. Appearance-Based Loop Closure Detection for Online Large-Scale and Long-Term Operation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2013, 29, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillot, P.; Perrot, A.; Hartley, A. Effects of Interactive Physical-Activity Video-Game Training on Physical and Cognitive Function in Older Adults. Psychol. Aging 2012, 27, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahan, A. Immersion, Engagement, and Presence: A Method for Analyzing 3-d Video Games. In The Video Game Theory Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kempka, M.; Wydmuch, M.; Runc, G.; Toczek, J.; Jaskowski, W. ViZDoom: A Doom-Based AI Research Platform for Visual Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computatonal Intelligence and Games, CIG, Santorini, Greece, 20–23 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, R.P.; Bowman, D.A.; Zielinski, D.J.; Brady, R.B. Evaluating Display Fidelity and Interaction Fidelity in a Virtual Reality Game. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2012, 18, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, C.; Boot, W.R.; Voss, M.W.; Kramer, A.F. Can Training in a Real-Time Strategy Video Game Attenuate Cognitive Decline in Older Adults? Psychol. Aging 2008, 23, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D. Cooperative Pathfinding. In Proceedings of the 1st Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment Conference, AIIDE 2005, Marina Del Rey, CA, USA, 1–2 June 2005; pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, S.; Anderson, A. Saying What You Mean in Dialogue: A Study in Conceptual and Semantic Co-Ordination. Cognition 1987, 27, 181–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbiadini, A.; Baldissarri, C.; Durante, F.; Valtorta, R.R.; De Rosa, M.; Gallucci, M. Together Apart: The Mitigating Role of Digital Communication Technologies on Negative Affect During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 554678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Wohl, M.J.A.; Salmon, M.M.; Gupta, R.; Derevensky, J. Do Social Casino Gamers Migrate to Online Gambling? An Assessment of Migration Rate and Potential Predictors. J. Gambl. Stud. 2014, 31, 1819–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Alexander, J.; Thomas, P. Publications Output: U.S. Trends and International Comparisons; Technical Report NSB-2023–33; National Science Board: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb202333/publication-output-by-region-country-or-economy-and-by-scientific-field (accessed on 5 March 2025).

| Class | Subclass | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skill-and-action games | Combat games | Players must destroy the opposing force; the challenge is to position oneself to avoid being hit by the enemy. | Space Invaders |

| Maze games | These games are characterized by a maze of paths through which the player must move, sometimes while being pursued by enemies. | Pac-Man | |

| Sports games | These are based on real-world sports but bear little resemblance to actual gameplay. | Tennis | |

| Paddle games | Players use a ball as a weapon to batter and must catch or deflect the ball. | Arkanoid | |

| Race games | Players must reach the finish line while avoiding various hazards on the route. | Pole Position | |

| Miscellaneous games | These concern all skill-and-action games not fitting into the above categories. | Qix | |

| Strategy games | Adventures | Players move through a complex world, accumulating tools and booty to overcome obstacles, aiming for the ultimate treasure or goal; obstacles are static and become trivial once solved. | Raiders of the Lost Ark |

| D&D games | These resemble non-digital fantasy roleplaying games; players gather treasure and defeat opponents, with the computer serving as the game master. | Pool of Radiance | |

| Wargames | These feature complicated rules and long play times; they may be computer versions of boardgames or original computer games. | Eastern Front (1941) | |

| Educational/Children’s | These are designed with explicit educational goals in mind. | Hangman | |

| Interpersonal games | These games focus on relationships between individuals or groups (e.g., gossip groups). | Trust & Betrayal |

| Genre | Description | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Abstract | Such games feature nonrepresentational graphics; objectives are not organized as a narrative. | Arkanoid |

| Adaptation | Representative games are adapted from another medium or gaming activity, closely following a narrative from another work. | Spy vs. Spy |

| Adventure | These games are set in a world of multiple, connected rooms/screens; solving objectives requires the completion of multiple steps (e.g., finding keys, unlocking doors, etc.). | The Secret of Monkey Island |

| Artificial Life | Such games involve growth/maintenance of digital creatures that can die without care. | The Sims |

| Board Games | These games are adaptations or similar to existing board games. | Chess, Monopoly |

| Capturing | Primary objective: capture objects that try to evade the player. | Keystone Kapers |

| Card Games | These are adaptations of existing or newly designed card-based games. | Solitaire |

| Catching | Primary objective: catch objects that do not actively evade the player. | Circus Atari |

| Chase | Games involve chasing or being chased. | Out Run |

| Collecting | Primary objective: collect stationary objects or surround areas. | Pac-Man, Qix |

| Combat | Players shoot projectiles at each other, using similar weaponry. | Outlaw |

| Demo | Demos allow players to try out a game for free. | |

| Diagnostic | This type is designed to test system functioning and is not a game in and of itself. | |

| Dodging | Primary objective: avoid projectiles or moving objects. | Frogger |

| Driving | These games require driving skills: steering, maneuverability, speed, and fuel conservation. | Pole Position |

| Educational | Such games are designed to teach the players; the main objective involves learning. | Museum Madness |

| Escape | Main objective: escape pursuers or an enclosure. | Maze Craze |

| Fighting | Such games entail hand-to-hand combat in a one-on-one scenario, with no firearms/projectiles. | Mortal Kombat |

| Flying | Representative games require flying skills: steering, altitude, takeoff/landing, maneuverability, speed, and fuel. | Descent |

| Gambling | Games involve betting a stake; assets increase or decrease in rounds. | Video Poker |

| Interactive Movie | Corresponding games involve branching video clips, with players’ decisions affecting the outcome. | Dragon’s Lair |

| Management Simulation | Balance limited resources to build/expand an institution/empire, and deal with opposition and competition. | Railroad Tycoon |

| Maze | Objective: successfully navigate a maze. | Doom |

| Obstacle Course | Traverse a difficult path with obstacles, entailing running, jumping, and avoiding danger. | Pitfall! |

| Pencil-and-Paper Games | Such games are adaptations of games played with a pencil and paper. | Tic-Tac-Toe |

| Pinball | Corresponding games simulate pinball games. | Pinball Fantasies |

| Platform | Move through levels by running, climbing, or jumping. | Super Mario Bros. |

| Programming Games | Players write programs to control agents within a game. | RobotWar |

| Puzzle | Solve enigmas, use tools, and manipulate objects to find solutions. | Lemmings |

| Quiz | Objective: successfully answer questions. | You Don’t Know Jack |

| Racing | Objective: win a race. | Mario Kart 64 |

| Rhythm and Dance | Players keep time with a musical rhythm. | Beatmania |

| Role-Playing | Players create/take on a character with various statistics. | Fallout |

| Shoot ’Em Up | Shoot at a series of opponents or objects. | Centipede |

| Simulation | This category includes any form of simulation. | Fortune Builder |

| Sports | Corresponding games are adaptations or variations of existing sports. | Kick Off |

| Strategy | These games emphasize strategy over fast action or quick reflexes. | Othello |

| Table-Top Games | These are adaptations of table-top games requiring physical skill or action. | Pool |

| Target | Primary objective: aim and shoot at targets. | Missile Command |

| Text Adventure | Gameplay primarily consists of a text-based interface and world description. | Zork |

| Training Simulation | Simulate realistic situations for training physical skills (e.g., steering). | Flight Unlimited |

| Utility | This category has purposes beyond entertainment. | Mario Teaches Typing |

| Meta Category | Category | Options (Examples) |

|---|---|---|

| Space | Perspective | Omni-present (e.g., Chess), Vagrant (e.g., Doom) |

| Topography | Geometrical (e.g., Doom), Topological (e.g., Chess) | |

| Environment | Dynamic (e.g., Lemmings), Static | |

| Time | Pace | Realtime (e.g., StarCraft), Turn-Based (e.g., Chess) |

| Representation | Mimetic (e.g., Morrowind), Arbitrary (e.g., Age of Empires) | |

| Teleology | Finite, Infinite | |

| Player Structure | Player Structure | Singleplayer, Two-Player, Multi-Player, Single-Team, Two-Team, Multi-Team |

| Control | Mutability | Static, Powerups, Experience-Leveling |

| Savability | Non-saving, Conditional, Unlimited | |

| Determinism | Deterministic, Non-Deterministic | |

| Rules | Topological rules | Yes, No |

| Time-based rules | Yes, No | |

| Objective-based rules | Yes, No |

| Meta Category | Category | Options |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual space | Perspective | Omni-present, vagrant |

| Positioning | Absolute, relative | |

| Environment Dynamics | None, fixed, free | |

| Physical space | Perspective | Omni-present, vagrant |

| Positioning | Location-based, proximity-based, both | |

| Internal time | Perspective | Present, absent |

| Synchronicity | Present, absent | |

| Interval control | Present, absent | |

| External time | Representation | Mimetic, arbitrary |

| Teleology | Finite, infinite | |

| Player composition | Composition | Singleplayer, two-player, multi-player, single-team, two-team, multi-team |

| Player relation | Bond | Dynamic, static |

| Evaluation | Individual, team, both | |

| Struggle | Challenge | Predefined, instanced, adversary |

| Goals | Explicit, implicit | |

| Game state | Mutability | Temporal, finite, infinite |

| Savability | None, conditional, unlimited |

| Layer | Sublayer | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Platform | The material medium used to implement a game (e.g., console, computer, gaming board, football field) |

| Physical Interface | The physical means used by players (e.g., gamepad, joystick, baseball bat) | |

| Behavioral | Physical actions required for play (e.g., pushing buttons, moving a piece, kicking a ball) | |

| Structural | Computational | The game’s software |

| Mechanical | Game mechanics (rules and systems) | |

| Economic | How the game is initiated, sustained, and finished in economic terms (e.g., inserting a coin in an arcade) | |

| Communicational | Presentational | Aesthetic aspects of the game |

| Semantic | Semantic information communicated (from simple commands to whole narratives) | |

| Interface | Non-diegetic information communicated to the player | |

| Mental | Phenomenal | How the game is experienced by the player |

| Conceptual | How the player understands the game | |

| Social | How players interact and perceive each other in the game |

| Facet | No. of Foci | Examples of Foci |

|---|---|---|

| Gameplay | 10 | Action, Fighting, RPG, Strategy |

| Style | 100 | Under gameplay: Action—Beat ’Em Up, Platformer, Rhythm; Under gameplay: Shooter—Shmup, Light Gun, Run and Gun |

| Purpose | 7 | Education, Entertainment, Party |

| Target Audience | 18 | Everyone (ESRB), 12+ (iTunes), MA-17 (VRC) |

| Presentation | 10 | 2D, 3D, Grid-Based, Side Scrolling |

| Artistic style | 9 | Abstract, Cel-Shaded, Retro |

| Temporal Aspect | 7 | Real-time, Turn-based, Multiple Game Clocks, Timed Action |

| Point-of-view | 4 | First-Person, Third-Person, Overhead, Multiple Perspectives |

| Theme | 22 parent 127 child | Nature: Animals, Dinosaurs Food: Restaurant, Bakery Fantasy: Princess, Knights Sports: Baseball, Basketball |

| Setting–Spatial | 16 | Casino, Spaceship, Western, Urban |

| Setting–Temporal | 8 | Medieval, Modern, Futuristic, Steampunk |

| Mood/Affect | 15 | Horror, Humorous, Dark, Peaceful |

| Type of ending | 5 | Finite, Branching, Circuitous, Infinite, Post-game |

| Type | Description | Subtypes |

|---|---|---|

| Action | Games that revolve around a fast-paced experience, often emphasizing reaction-based challenges in terms of how the player interacts with the game world. | Action–Adventure, Arcade, Block Breaking, Brawler, Fighting, Hack and Slash, Multiplayer Online Battle Arena, Music, Party, Platform, Stealth, Survival, Vehicle Combat |

| Puzzle | Games that emphasize solving puzzles and/or organizing pieces. | Block Fill, Hidden Object, Match Puzzles, Point and Click, Word Puzzles |

| Rhythm | Games that involve the player inputting commands or completing actions while synchronizing to a rhythm. | – |

| Role-Playing | Games related to tabletop role-playing, involving a heavy focus on the statistical advancement (like “leveling up”) of characters, combined with exploration. | Japanese RPG, Massively Multiplayer Online RPG, Rogue-Like, Western RPG |

| Simulation | Games that simulate actions or situations based on either an existing or fictional reality. | Breeding, Construction and Management Simulation, Flight Simulator, God Game, Interactive Movie, Programming Game, Sandbox, Social Simulator, Virtual Life, Visual Novel |

| Sports | Games that simulate real-world sports. | Racing |

| Shooter | Games that are based on a shooting mechanic where players target and shoot objects or enemies to progress. | First-Person Shooter, Light-Gun Shooter |

| Strategy | Games that revolve around strategic or tactical planning, often involving building, resource management, and exploration components. | 4X, Military Simulator, Real-Time Strategy, Tactics, Tower Defense, Turn-Based Strategy |

| Traditional | Games based on mechanics that exist in the real world and can be played in a physical setting. | Board Games, Card Games, Exercise, Gambling, Game Shows, Mazes, Pinball, Puzzles, Trivia Games |

| Genre | Also in | Alternative Names | Close Genres | Subset or Superset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | [22,23,31,32,33] | Skill-and-Action [20] | Capturing [10], Catching [10], Collecting [10], Dodging [10] | |

| Puzzle | [10,23,31,32,33] | Adventure [20,22] | ||

| Rhythm | [33] | Rhythm and Dance [10] | Kinetic-controlled [23], Music [31,32] | Miscellaneous [20] |

| Role-Playing | [10,23,31,32] | D&D Games [20], Role Play [22], RPG [33] | ||

| Simulation | [10,23,31,32,33] | |||

| Sports | [10,20,23,31,32,33] | |||

| Shooter | [33] | Shoot’ Em Up [10], Target [10], Combat [20], First-Person Shooter [23] | ||

| Strategy | [10,20,31,32,33] | Resource [22] | Real-Time strategy [23], Turn-Based [23] | |

| Traditional | Adaptation [10] | Board [31,32,33], Card [31,32,33], Casino [31,32]/Gambling [33], Trivia [31,32,33], Word [31,32,33] |

| Genre | Citations of Top 10 papers | Most Cited Papers |

|---|---|---|

| Action | 3170 | [53,54,55] |

| Puzzle | 2042 | [56,57,58] |

| Rhythm | 430 | [59,60,61] |

| Role-Playing | 3635 | [62,63,64] |

| Simulation | 3920 | [65,66,67] |

| Sports | 2526 | [68,69,70] |

| Shooter | 2442 | [71,72,73] |

| Strategy | 3219 | [55,74,75] |

| Traditional | 1079 | [76,77,78] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Swacha, J. The Relative Popularity of Video Game Genres in the Scientific Literature: A Bibliographic Survey. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9060059

Swacha J. The Relative Popularity of Video Game Genres in the Scientific Literature: A Bibliographic Survey. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2025; 9(6):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9060059

Chicago/Turabian StyleSwacha, Jakub. 2025. "The Relative Popularity of Video Game Genres in the Scientific Literature: A Bibliographic Survey" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 9, no. 6: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9060059

APA StyleSwacha, J. (2025). The Relative Popularity of Video Game Genres in the Scientific Literature: A Bibliographic Survey. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 9(6), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9060059