Does Augmented Reality Help to Understand Chemical Phenomena during Hands-On Experiments?–Implications for Cognitive Load and Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical and Empirical Background

- Concrete: The model is expressed by real materials and is often three-dimensional.

- Verbal: The model is expressed by using language, for example, by describing the structure of molecules or their reaction with each other.

- Symbolic: The model is expressed by symbols such as mathematical equations or chemical formulas.

- Visual: The model is expressed by visualizations such as images or animations. This also includes virtual models.

- Gestural: The model is expressed by body actions such as gestures or body movements.

- Combination of virtual and real objects partly overlaying each other;

- Real-time interaction;

- Three-dimensional objects.

1.2. Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

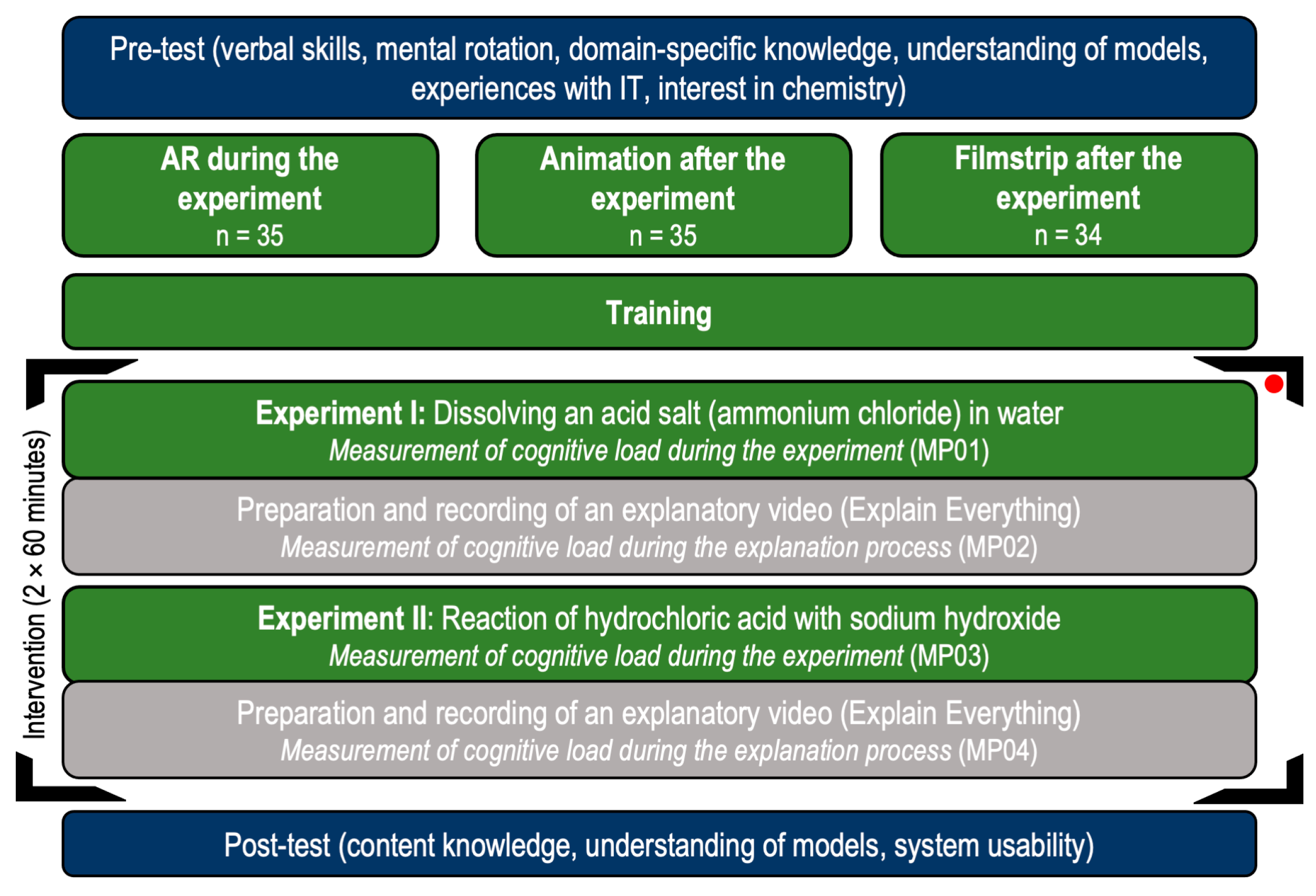

2.1. Study Design

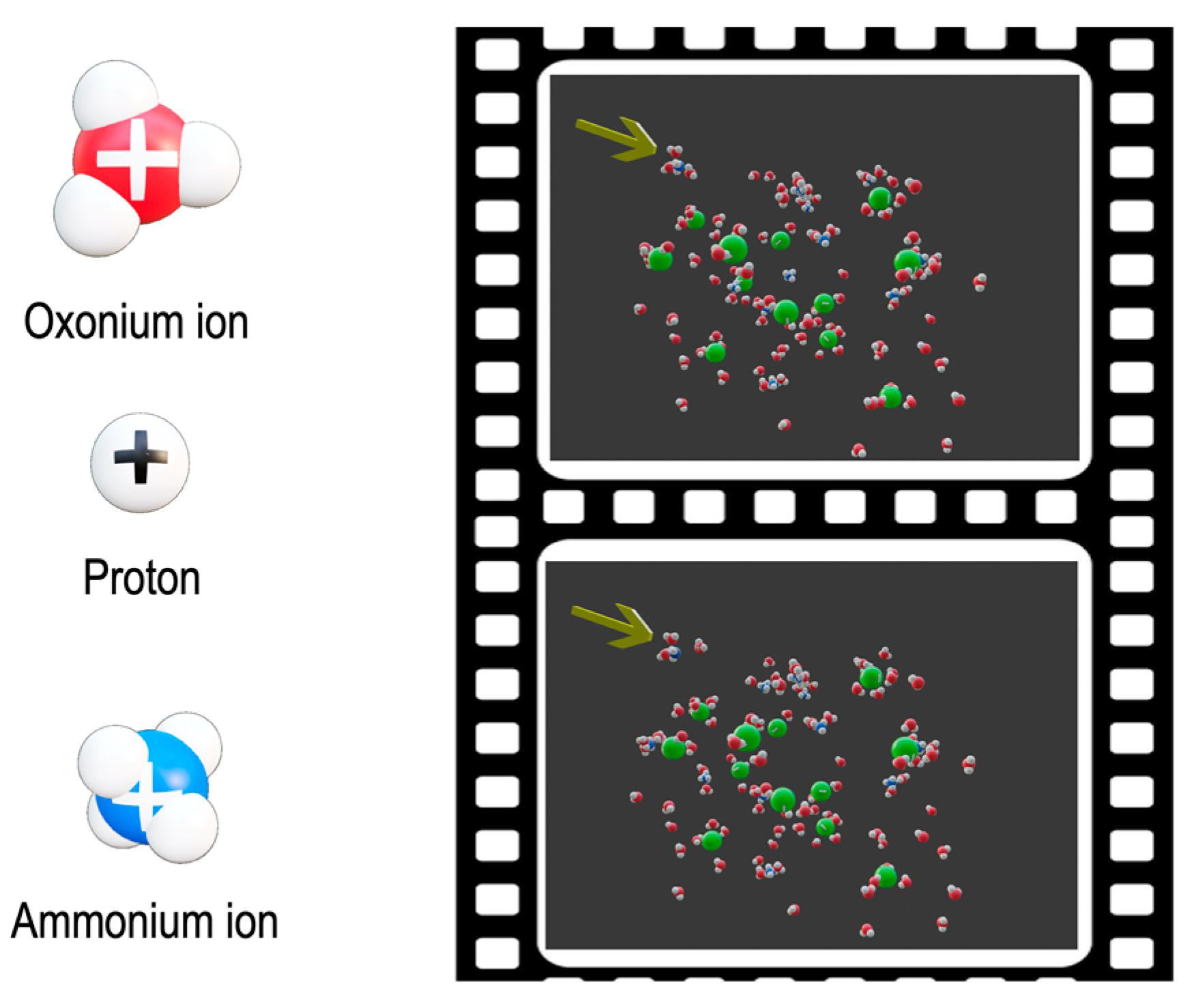

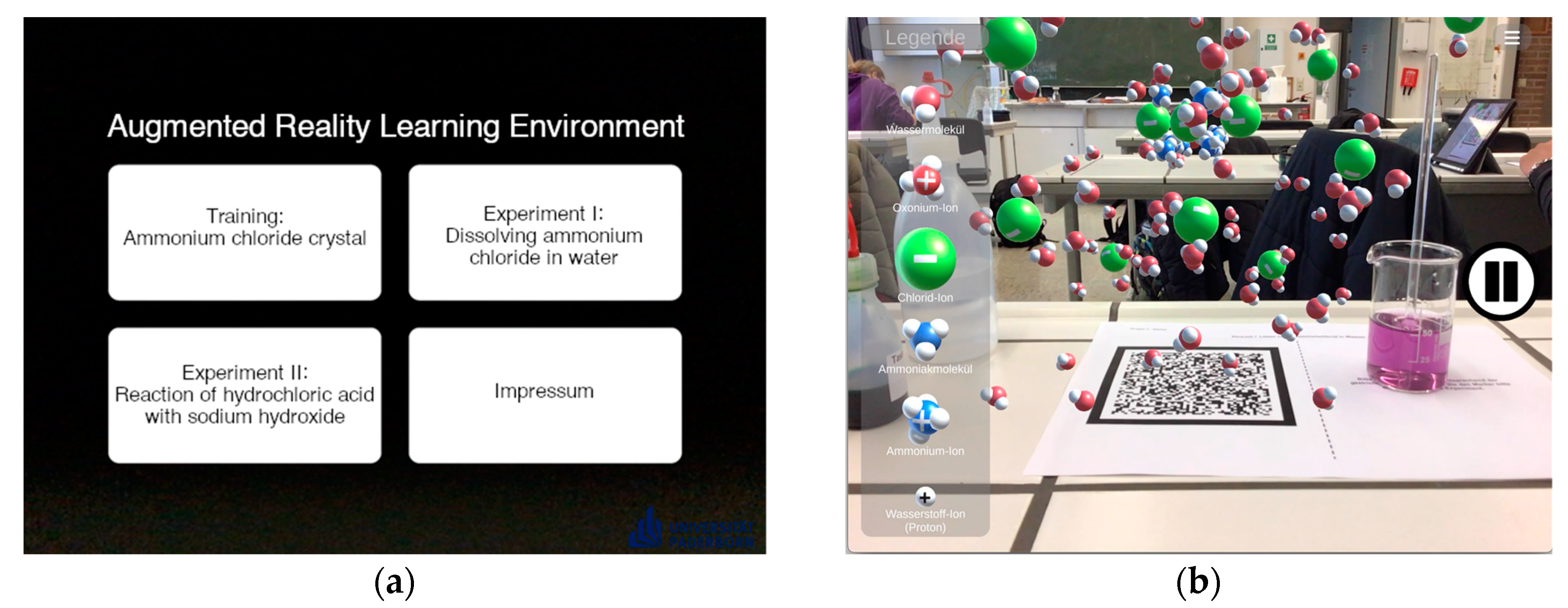

2.2. Learning Materials

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Sample

2.5. Balancing of Groups

3. Results

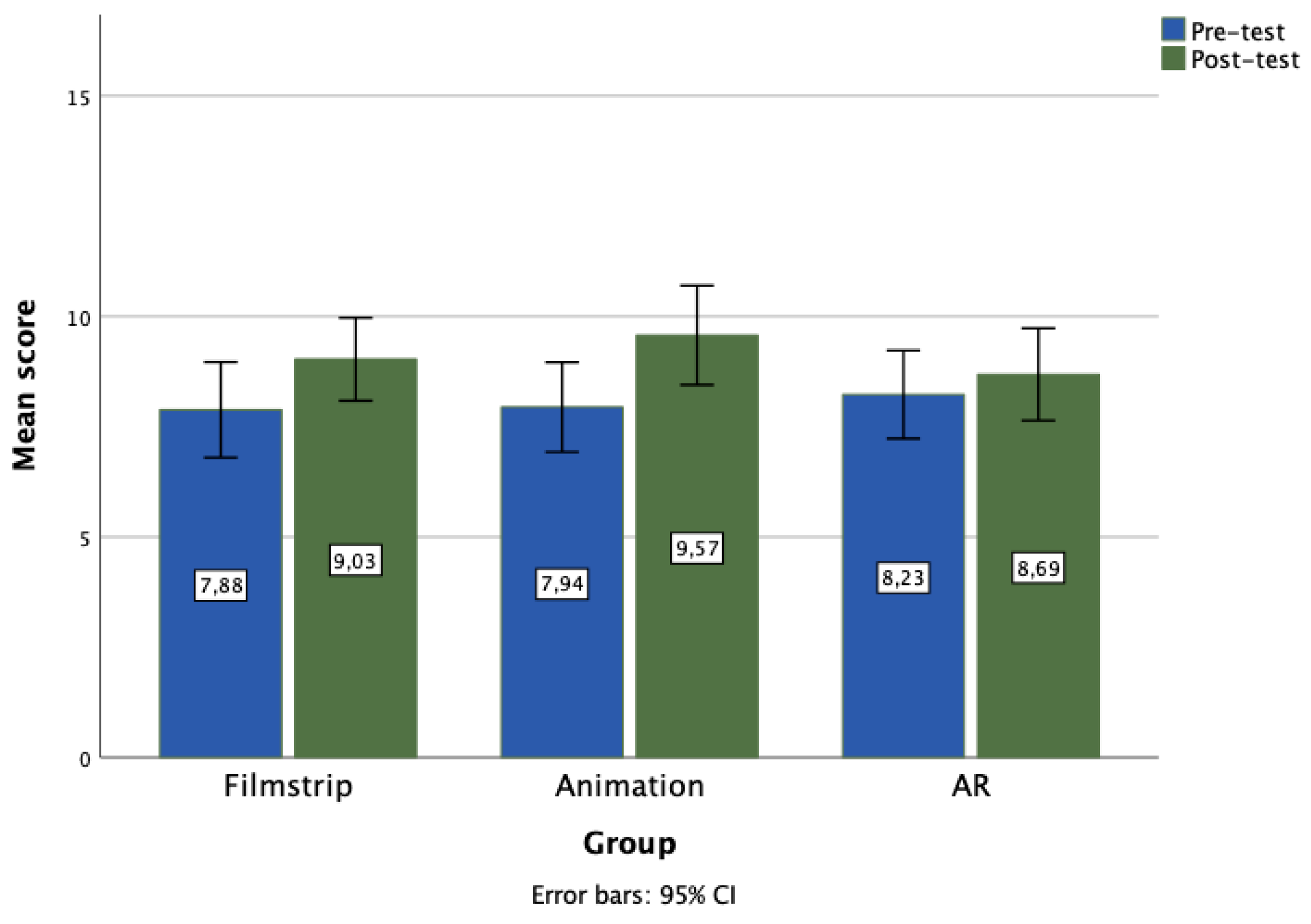

3.1. Domain-Specific Knowledge

3.2. Cognitive Load

4. Discussion

4.1. Domain-Specific Knowledge

4.2. Cognitive Load

4.3. Limitations and Outlook

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Score Pre-test | Score Post-Test | ICL_MP01 | GCL_MP01 | ECL_MP01 | ICL_MP03 | GCL_MP03 | ECL_MP03 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score Pre-test | ||||||||

| Score Post-Test | 0.604 ** | |||||||

| ICL_MP01 | −0.165 | 0.033 | ||||||

| GCL_MP01 | −0.127 | −0.066 | −0.040 | |||||

| ECL_MP01 | 0.127 | 0.100 | −0.027 | −0.281 * | ||||

| ICL_MP03 | −0.289 * | −0.256 * | 0.250 * | 0.001 | 0.045 | |||

| GCL_MP03 | −0.157 | −0.044 | 0.001 | 0.334 ** | −0.202 | 0.287 * | ||

| ECL_MP03 | −0.214 | −0.161 | 0.109 | −0.283 * | 0.318 ** | 0.475 ** | 0.047 |

| Pre-Test score | Post-Test score | ICL_MP01 | GCL_MP01 | ECL_MP01 | ICL_MP03 | GCL_MP03 | ECL_MP03 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test score | ||||||||

| Post-test score | 0.638 ** | |||||||

| ICL_MP01 | 0.132 | −0.106 | ||||||

| GCL_MP01 | 0.258 | 0.176 | 0.370 * | |||||

| ECL_MP01 | −0.152 | −0.144 | 0.182 | −0.447 * | ||||

| ICL_MP03 | −0.146 | −0.292 | 0.328 | −0.099 | 0.446 ** | |||

| GCL_MP03 | 0.107 | 0.046 | 0.145 | 0.129 | 0.012 | 0.161 | ||

| ECL_MP03 | −0.360 * | −0.402 * | 0.141 | −0.346 * | 0.529 ** | 0.544 ** | −0.081 |

References

- Scavarelli, A.; Arya, A.; Teather, R.J. Virtual reality and augmented reality in social learning spaces: A literature review. Virtual Real. 2021, 25, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, J.; Pavón, J.; Baldiris, S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of augmented reality in educational settings. Virtual Real. 2019, 23, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmigniani, J.; Furht, B.; Anisetti, M.; Ceravolo, P.; Damiani, E.; Ivkovic, M. Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2011, 51, 341–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M.J.; Hughes, J.M. Virtual, augmented and mixed reality in K–12 education: A review of the literature. Technol. Pegagogy Educ. 2020, 29, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, R.T. A survey of augmented reality. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1997, 6, 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, M.; Volmerg, J.S.; Friedrich, C.M. Augmented reality in medicine: Systematic and bibliographic review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2019, 7, e10967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattullo, M.; Scurati, G.W.; Fiorentino, M.; Uva, A.E.; Ferrise, F.; Bordegoni, M. Towards augmented reality manuals for industry 4.0: A methodology. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2019, 56, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, J. An overview of twenty-five years of augmented reality in education. MTI 2021, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacca Acosta, J.L.; Baldiris Navarro, S.M.; Fabregat Gesa, R.; Graf, S. Augmented reality trends in education: A systematic review of research and applications. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2014, 17, 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.-W.; Su, C.-Y.; Hu, Y.; Chen, C.-H. Exploring the effectiveness and moderators of augmented reality on science learning: A meta-analysis. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2022, 31, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkitzia, V.; Salta, K.; Tzougraki, C. Students’ competence in translating between different types of chemical representations. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2020, 21, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, A.H. The development of chemistry teaching: A changing response to a changing demand. J. Chem. Educ. 1993, 70, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. Three levels of chemistry educational research. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2013, 14, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, R.B.; Russell, J. Multimedia and understanding: Expert and novice responses to different representations of chemical phenomena. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1997, 34, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidowitz, B.; Chittleborough, G.D.; Murray, E. Student-generated submicro diagrams: A useful tool for teaching and learning chemical equations and stoichiometry. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2010, 11, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, V.; Freire, S.; Baptista, M. Constructing scientific explanations: A system of analysis for students’ explanations. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.K. Models and modelling: Routes to more authentic science education. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2004, 2, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisi, P.-L.; Thomas, R.M. The pictographic molecular paradigm. Naturwissenschaften 1990, 77, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giere, R.N. An agent-based conception of models and scientific representation. Synthese 2010, 172, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedaste, M.; Mäeots, M.; Siiman, L.A.; De Jong, T.; Van Riesen, S.A.; Kamp, E.T.; Manoli, C.C.; Zacharia, Z.C.; Tsourlidaki, E. Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 14, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, P.; Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory and the Format of Instruction. Cogn. Instr. 1991, 8, 293–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J.; Ayres, P.; Kalyuga, S. Cognitive Load Theory, 1st ed.; Springer Science+Business Media LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-8125-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sweller, J. Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 22, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.G.W.C.; Sweller, J. Implication of cognitive load theory for multimedia learning. In Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning, 2nd ed.; Mayer, R.E., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.E.; Fiorella, L. Principles for reducing extraneous processing in multimedia learning: Coherence, signaling, redundancy, spatial contiguity, and temporal contiguity principle. In Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning, 2nd ed.; Mayer, R.E., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 279–315. [Google Scholar]

- Höffler, T.N.; Leutner, D. Instructional animation versus static pictures: A meta-analysis. Learn. Instr. 2007, 17, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berney, S.; Bétrancourt, M. Does animation enhance learning? A meta-analysis. Comput. Educ. 2016, 101, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, P.; Takemura, H.; Utsumi, A.; Kishino, F. Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum. Proc. SPIE-Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 1994, 2351, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçayır, M.; Akçayır, G. Advantages and challenges associated with augmented reality for education: A systematic review of the literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, J.; Acevedo, J. Meta-analysis of the impact of augmented reality on students’ learning gains. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuco, A.; Krassmann, A.L.; Reategui, E.; Gomes, R.S. A systematic review of augmented reality in chemistry education. Rev. Educ. 2022, 10, e3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmeyer, K.; Kapp, S.; Thees, M.; Malone, S.; Kuhn, J.; Brünken, R. The use of augmented reality to foster conceptual knowledge acquisition in STEM laboratory courses—Theoretical background and empirical results. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thees, M.; Kapp, S.; Strzys, M.P.; Beil, F.; Lukowicz, P.; Kuhn, J. Effects of augmented reality on learning and cognitive load in university physics laboratory courses. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yu, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, Q.; Xu, S. The effects of an augmented reality based magnetic experimental tool on students’ knowledge improvement and cognitive load. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2021, 37, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habig, S. Who can benefit from augmented reality in chemistry? Sex differences in solving stereochemistry problems using augmented reality. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.; Rumann, S.; Habig, S. Cognitive load implications for Augmented Reality supported chemistry learning. Information 2021, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Wang, X.; Chiang, F.-K. A case study of augmented reality simulation system application in a chemistry course. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Alfaro, J.L.; Gantois, S.; Blattgerste, J.; de Croon, R.; Verbert, K.; Pfeiffer, T.; van Puyvelde, P. Mobile augmented reality laboratory for learning acid–base titration. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Han, M.; Su, Z.; Li, W.; Pan, Z. An augmented reality-based multimedia environment for experimental education. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltun, W.L. Precision space-filling atomic models. Biopolymers 1965, 3, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, K.A.; Perleth, C. Kognitiver Fähigkeitstest für 4. bis 12. Klassen (Cognitive Abilities Test for Year 4 to 12); Beltz Testgesellschaft: Göttingen, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.Y. Psychometric Properties of the Revised Purdue Spatial Visualization Tests: Visualization of Rotations (the Revised PSVT:R). Ph.D. Thesis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bodner, G.M.; Guay, R.B. The purdue visualization of rotations test. Chem. Educ. 1997, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A ‘quick and dirty’ usability scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry, 1st ed.; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., Weerdmeester, B.A., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bangor, A.; Kortum, P.; Miller, J. Determining what individual SUS scores mean: Adding an adjective rating scale. J. Usability Stud. 2009, 4, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ropohl, M. Modellierung von Schülerkompetenzen im Basiskonzept Chemische Reaktion. Entwicklung und Analyse von Testaufgaben (Modeling Student Competencies in the Basic Concept of Chemical Reaction. Development and Analysis of Test Items); Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kehne, F. Analyse des Transfers von Kontextualisiert Erworbenem Wissen im Fach Chemie (Analysis of the Transfer of Contextualized Acquired Knowledge in Chemistry); Logos: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Akman, P. Konkret Oder Abstrakt?: Externe Repräsentationen bei der Informationsentnahme und im Modellierprozess aus Lernerperspektive (Concrete or Abstract?: External Representations in Information Retrieval and in the Modeling Process from the Learner’s Perspective). Ph.D. Thesis, Paderborn University, Paderborn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Klepsch, M.; Schmitz, F.; Seufert, T. Development and validation of two instruments measuring intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781526419514. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Buchner, J.; Kerres, M. Media comparison studies dominate comparative research on augmented reality in education. Comput. Educ. 2023, 195, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | 𝛂 |

|---|---|

Domain-specific knowledge

| 0.705 0.708 |

| Verbal skills | 0.498 |

| Mental rotation | 0.788 |

Cognitive load (MP01) 1

| 0.728 0.521 0.675 |

Cognitive load (MP03) 1

| 0.776 0.590 0.690 |

| System Usability (n = 34) 2 | 0.863 |

| Measure | Filmstrip | Animation | AR | F(2, 101) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Domain-specific knowledge 1 | 7.88 | 3.10 | 7.94 | 2.96 | 8.22 | 2.91 | 0.04 (n.s.) |

| Verbal skills 2 | 7.21 | 2.56 | 7.14 | 2.66 | 7.03 | 2.64 | 0.00 (n.s.) |

| Mental rotation 2 | 13.12 | 3.30 | 13.17 | 4.00 | 13.11 | 3.81 | 0.13 (n.s.) |

| Group | Mean Difference | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filmstrip | 1.15 | 0.45 | 0.013 |

| Animation | 1.63 | 0.45 | <0.001 |

| AR | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.306 |

| Measure | No-AR | AR | t(102) | p | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Intrinsic 1 | 1.33 | 0.48 | 2.00 | 0.95 | 3.94 | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| Germane | 4.16 | 1.18 | 4.45 | 1.48 | 1.08 | 0.285 | 0.22 |

| Extraneous | 2.18 | 1.16 | 2.66 | 1.32 | 1.90 | 0.061 | 0.39 |

| Measure | No-AR | AR | t(99) | p | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Intrinsic 1 | 1.61 | 0.85 | 2.36 | 1.13 | 3.45 | 0.001 | 0.79 |

| Germane 1 | 4.07 | 1.43 | 4.71 | 1.09 | 2.53 | 0.013 | 0.49 |

| Extraneous | 1.97 | 1.03 | 2.64 | 1.20 | 2.90 | 0.007 | 0.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peeters, H.; Habig, S.; Fechner, S. Does Augmented Reality Help to Understand Chemical Phenomena during Hands-On Experiments?–Implications for Cognitive Load and Learning. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti7020009

Peeters H, Habig S, Fechner S. Does Augmented Reality Help to Understand Chemical Phenomena during Hands-On Experiments?–Implications for Cognitive Load and Learning. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2023; 7(2):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti7020009

Chicago/Turabian StylePeeters, Hendrik, Sebastian Habig, and Sabine Fechner. 2023. "Does Augmented Reality Help to Understand Chemical Phenomena during Hands-On Experiments?–Implications for Cognitive Load and Learning" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 7, no. 2: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti7020009

APA StylePeeters, H., Habig, S., & Fechner, S. (2023). Does Augmented Reality Help to Understand Chemical Phenomena during Hands-On Experiments?–Implications for Cognitive Load and Learning. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 7(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti7020009