Reviews of Social Embodiment for Design of Non-Player Characters in Virtual Reality-Based Social Skill Training for Autistic Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Skill Training in Virtual Reality

1.2. Roles of Non-Player Characters in VR

1.3. Social Embodiment in Designing a Social Robot

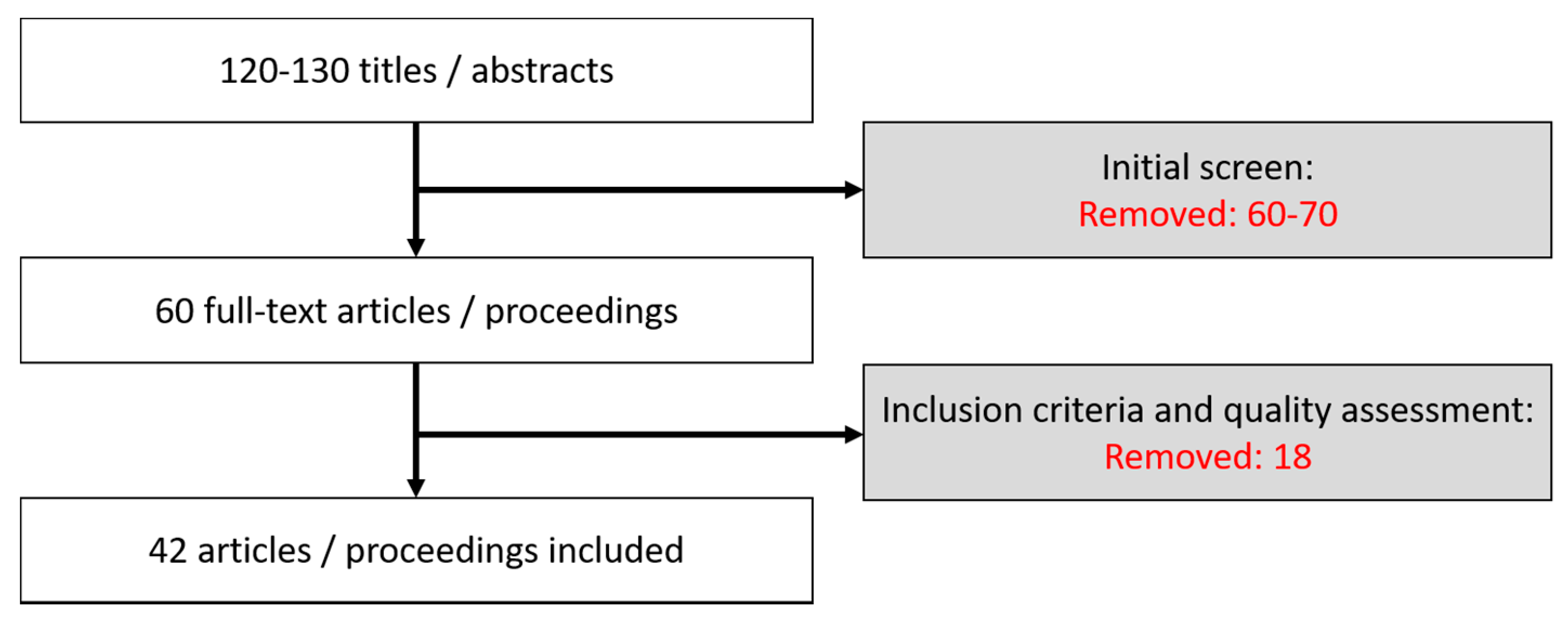

2. Method

- PSYINFO: Governed by the American Psychological Association, this database carries out searching for relevant citation sources from a great number of journal articles in psychology and education fields.

- ACM (Association for Computing Machinery): This database is particularly useful for accessing empirical studies demonstrating how computer-based system applications have been exploited.

- ScienceDirect: This database is remarkable, and includes a large amount of scientific and medical research published by Elsevier. It provides free article abstracts with affordable full-text services for peer-reviewed journal articles.

- Google Scholar: This database allows users to find extensive results for relevant literatures. This website filters in many academic sources from publishers and scholarly societies.

Inclusion Criteria

3. Findings

3.1. Activation of Bodily-Initiated Experiences

3.1.1. Facial Mimicry

3.1.2. Simulation of Body Gestures

3.2. Design Features of Non-Player Characters in Social Skill Training

3.2.1. Emotional Modeling of Non-Player Characters

3.2.2. Naturalistic Design of Social Skill Training

3.2.3. Authentic Social Scenario Design

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ke, F.; Whalon, K.; Yun, J. Social skill interventions for youth and adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 88, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhland, K.; Peters, C.E.; Andrist, S.; Badler, J.B.; Badler, N.I.; Gleicher, M.; Mutlu, B.; McDonnell, R. A review of eye gaze in virtual agents, social robotics and hci: Behaviour generation, user interaction and perception. Comput. Graph. Forum. 2015, 34, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, P.; Puglesi, C.; Borràs-Comes, J.; Arroyo, E.; Blat, J. Exploring the contribution of prosody and gesture to the perception of focus using an animated agent. J. Phon. 2015, 49, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigsti, I.-M. A review of embodiment in autism spectrum disorders. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.E.; Tager-Flusberg, H.E.; Cohen, D.J. Understanding Other Minds: Perspectives from Autism; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, P. Introduction to Theory of Mind: Children, Autism and Apes; Edward Arnold Publishers: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Happé, F.; Frith, U. The weak coherence account: Detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 36, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happé, F.G. Studying weak central coherence at low levels: Children with autism do not succumb to visual illusions. A research note. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 1996, 37, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, J.J.; Baggett, B.A.; Fox, J.; Blevins, L. Treatment integrity: A review of intervention studies conducted with children with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2006, 21, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Lo, Y.-Y.; Tsai, S.; Cartledge, G. The effects of theory-of-mind and social skill training on the social competence of a sixth-grade student with autism. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2008, 10, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, S. Social skill deficits and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2004, 19, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, S.; Mitchell, P. The potential of virtual reality in social skills training for people with autistic spectrum disorders. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2002, 46, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, F.; Im, T. Virtual-reality-based social interaction training for children with high-functioning autism. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 106, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, M.; Sabouret, N.; Corruble, V. Simulation of the dynamics of nonplayer characters’ emotions and social relations in games. IEEE Trans. Comput. Intell. AI Games 2009, 1, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.A. Social stories and comic strip conversations with students with asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. In Asperger Syndrome or High-Functioning Autism? Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 167–198. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J.L.; Bird, G. Atypical social modulation of imitation in autism spectrum conditions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M. Six views of embodied cognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2002, 9, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.L. Embodied cognition: A field guide. Artif. Intell. 2003, 149, 91–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, R.; Lungarella, M.; Sporns, O. The synthetic approach to embodied cognition: A primer. In Handbook of Cognitive Science: An Embodied Approach; Elsevier Science: Oxford, UK, 2008; Chapter 7; pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Mennecke, B.E.; Triplett, J.L.; Hassall, L.M.; Conde, Z.J.; Heer, R. An examination of a theory of embodied social presence in virtual worlds*. Decis. Sci. 2011, 42, 413–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L.W.; Niedenthal, P.M.; Barbey, A.K.; Ruppert, J.A. Social embodiment. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 2003, 43, 43–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rueschemeyer, S.-A.; Lindemann, O.; van Elk, M.; Bekkering, H. Embodied cognition: The interplay between automatic resonance and selection-for-action mechanisms. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, B.R.; Dragone, M.; O’Hare, G.M. In Social Robot Architecture: A Framework for Explicit Social Interaction. 2005. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c9d6/33ab97ea713d9ba75a1248df7b5726deea1e.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2018).

- Breazeal, C.; Takanishi, A.; Kobayashi, T. Social robots that interact with people. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 1349–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Kizilcec, R.; Bailenson, J.; Ju, W. Social robots and virtual agents as lecturers for video instruction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, B. Robots social embodiment in autonomous mobile robotics. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2004, 1, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.A. Intelligence without representation. Artif. Intell. 1991, 47, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2017. Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-TW&lr=&id=335ZDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT19&ots=YCvUNIttsL&sig=x69KiaZpI2vrCVATj6VFMOucKp8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 6 July 2018).

- Clark, T.F.; Winkielman, P.; McIntosh, D.N. Autism and the extraction of emotion from briefly presented facial expressions: Stumbling at the first step of empathy. Emotion 2008, 8, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, D.N. Spontaneous facial mimicry, liking and emotional contagion. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 37, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Oberman, L.M.; Winkielman, P.; Ramachandran, V.S. Slow echo: Facial emg evidence for the delay of spontaneous, but not voluntary, emotional mimicry in children with autism spectrum disorders. Dev. Sci. 2009, 12, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dapretto, M.; Davies, M.S.; Pfeifer, J.H.; Scott, A.A.; Sigman, M.; Bookheimer, S.Y.; Iacoboni, M. Understanding emotions in others: Mirror neuron dysfunction in children with autism spectrum disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerasinghe, P.; Rajapakse, R.P.C.J.; Marasinghe, A. An empirical analysis on emotional body gesture for affective virtual communication. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Issues 2015, 12, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- So, W.-C.; Shum, P.L.-C.; Wong, M.K.-Y. Gesture is more effective than spatial language in encoding spatial information. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2015, 68, 2384–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fay, N.; Lister, C.J.; Ellison, T.M.; Goldin-Meadow, S. Creating a communication system from scratch: Gesture beats vocalization hands down. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hostetter, A.; Alibali, M. Visible embodiment: Gestures as simulated action. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2008, 15, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, P.A. Nonverbal Communication: Forms and Functions; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrogiuseppe, M.; Capirci, O.; Cuva, S.; Venuti, P. Gestural communication in children with autism spectrum disorders during mother–child interaction. Autism 2015, 19, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, I.M.; Bryson, S.E. Gesture imitation in autism: Ii. Symbolic gestures and pantomimed object use. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2007, 24, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Marchena, A.; Eigsti, I.M. Conversational gestures in autism spectrum disorders: Asynchrony but not decreased frequency. Autism Res. 2010, 3, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whalen, C.; Schreibman, L.; Ingersoll, B. The collateral effects of joint attention training on social initiations, positive affect, imitation, and spontaneous speech for young children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 36, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellawadi, A.B.; Weismer, S.E. Assessing gestures in young children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2014, 57, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedenthal, P.M.; Barsalou, L.W.; Winkielman, P.; Krauth-Gruber, S.; Ric, F. Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 9, 184–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, C. Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. J. Pragmat. 2000, 32, 1489–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, B.; Marchi, E.; Baron-Cohen, S.; O’Reilly, H.; Robinson, P.; Davies, I.; Golan, O.; Friedenson, S.; Tal, S.; Newman, S. Asc-inclusion: Interactive emotion games for social inclusion of children with autism spectrum conditions. In Proceedings of the 8th Foundations of Digital Games, Chania, Greece, 3–7 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gersten, R. Direct instruction with special education students: A review of evaluation research. J. Spec. Educ. 1985, 19, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.W.; Gilles, D.L. Using key instructional elements to systematically promote social skill generalization for students with challenging behavior. Interv. Sch. Clin. 2003, 39, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilov, Y.; Rotem, S.; Ofek, R.; Geva, R. Socio-cultural effects on children’s initiation of joint attention. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S.; Dunkel-Schetter, C.; DeLongis, A.; Gruen, R.J. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, E.V.; Sivanathan, A.; Lim, T.; Suttie, N.; Louchart, S.; Pillen, S.; Pineda, J.A. An effective neurofeedback intervention to improve social interactions in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 4084–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Laffey, J.; Xing, W.; Galyen, K.; Stichter, J. Fostering verbal and non-verbal social interactions in a 3d collaborative virtual learning environment: A case study of youth with autism spectrum disorders learning social competence in isocial. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2017, 65, 1015–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Laffey, J.; Xing, W.; Ma, Y.; Stichter, J. Exploring embodied social presence of youth with autism in 3d collaborative virtual learning environment: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; Lee, S. Virtual reality based collaborative design by children with high-functioning autism: Design-based flexibility, identity, and norm construction. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1511–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Simpson, A.; Danaher, K.; Haesen, J.; Makela, T.; Thomson, K. An evaluation of behavioral skills training for teaching caregivers how to support social skill development in their child with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 1957–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozonoff, S.; Miller, J.N. Teaching theory of mind: A new approach to social skills training for individuals with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1995, 25, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesibov, G.B. Social skills training with verbal autistic adolescents and adults: A program model. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1984, 14, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartaro, A.; Cassell, J. Authorable virtual peers for autism spectrum disorders. In Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Artificial Intellegence, Riva del Garda, Italy, 27 August–1 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Didehbani, N.; Allen, T.; Kandalaft, M.; Krawczyk, D.; Chapman, S. Virtual reality social cognition training for children with high functioning autism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Major Factors | Design Principles | Underlying Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Activation of bodily-initiated experience | Facial mimicry; | Facial elicitation; |

| Simulations of body gestures | Communicative mimicry Online embodiment | |

| Design features of non-player characters in social skill training | Emotional modeling; | Category priming; |

| Role specification | Entrenched situated conceptualizations | |

| Authentic social scenario |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moon, J. Reviews of Social Embodiment for Design of Non-Player Characters in Virtual Reality-Based Social Skill Training for Autistic Children. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2018, 2, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030053

Moon J. Reviews of Social Embodiment for Design of Non-Player Characters in Virtual Reality-Based Social Skill Training for Autistic Children. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2018; 2(3):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030053

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Jewoong. 2018. "Reviews of Social Embodiment for Design of Non-Player Characters in Virtual Reality-Based Social Skill Training for Autistic Children" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2, no. 3: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030053

APA StyleMoon, J. (2018). Reviews of Social Embodiment for Design of Non-Player Characters in Virtual Reality-Based Social Skill Training for Autistic Children. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 2(3), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030053