An Exploratory Study of the Uses of a Multisensory Map—With Visually Impaired Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

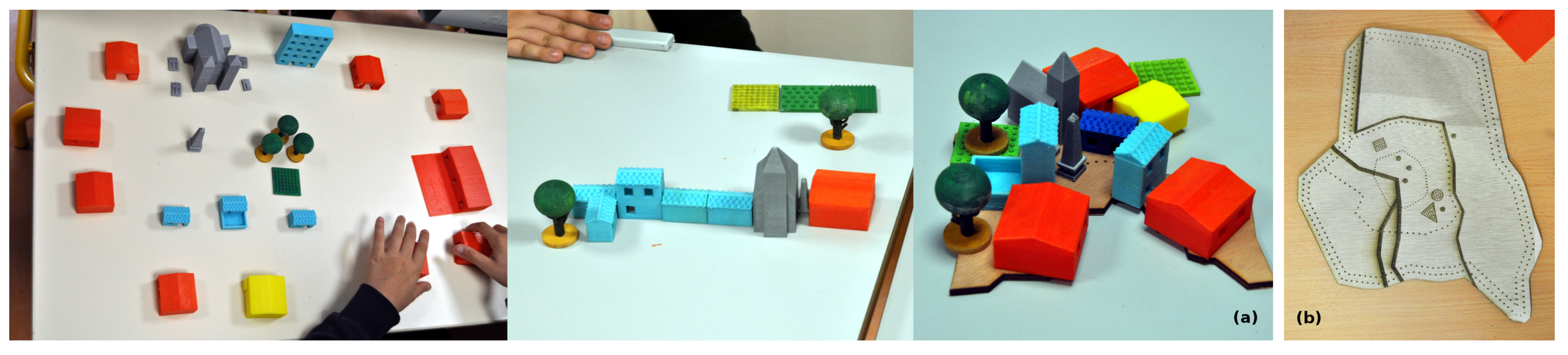

2. Design of the Prototype

2.1. Process

2.2. General Setup

2.3. Interaction Principles

2.4. Map

Tangibles

- housing: a farm, a building, two medium- and three small-sized houses;

- shops: a grocery store, a bank, a restaurant and a supermarket;

- services: two post offices and two schools of different sizes;

- infrastructure: an airport, two planes;

- green spaces: fields, parks and trees;

- historical points of interest: churches, tombs, war memorial;

2.5. Olfactory and Flavor Cues

- Similarity to something children had smelled during a previous field trip;

- Familiarity i.e., cues that all children are expected to have experienced in their daily lives;

- Or unknown cues that could introduce new experiences and meaning. Some cues were direct associations (e.g., colza oil for colza fields), others were metaphors (e.g., goat cheese for the farm).

3. Methods: Study Design

3.1. Context

Ethics

3.2. Research Questions

- How can children best be supported in making sense of multisensory material and how can it be integrated more often? What can we learn about children’s meaning-making processes when using smell and taste in the classroom for geography courses?

- Does multisensory material allow for more connections to be drawn between children’s lives, geography field-trips, and the classroom?

- How are these activities valued by pupils and teacher? Can this prototype be used to support collaboration in children with diverse sensory perceptions and diverse background?

3.3. Activity Design

3.4. Participants

3.5. Procedure

3.6. Analysis

- 1:41 h of video from the third lesson of the sequence (see Appendix C);

- Three interviews with the teacher: one before the three lessons to define the content, two after the lesson presented here. These last two interviews investigated among other things her assessment of learning outcomes;

- Semi-guided interviews with the children, conducted after this study. We discussed the session, what they remembered from it and the goals of learning (this last topic was useful for understanding how they perceived this unit compared to their other school experiences).

- Broad phases in the lesson: subtasks, moments of switching from a theme to another;

- Modes of interaction: overall classroom setting including the types of interactions with the map, speaker, utterance, gestures, gaze, olfactory representation, gustatory representation, and tangibles. Here, gaze is mainly denoted by body orientation, which suggests efforts to listen, focus on manipulation, etc.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Smell and Taste: (in)Congruities

or, in other words, less space for individuals. C2’s initial answer was a reference to a bodily and personal experience, but it is the smell of rubber that makes it fit into a larger pattern Let’s note the pollution due to agricultural activities was not discussed. It creates a false dichotomies between cities and countryside, or culture and nature. However, this should be understood as a first step to understand the link between human activities and pollution, which harnesses children’s beliefs about the difference between the countryside and cities, enabling appropriation. Here, the congruity between the experiences and the representation in the classroom is very visible: C2 discussed the lack of space as affecting the ability to breathe—When manipulating the rubber C5 turned his head away to signify disgust, and C1 agitated his hands under his nose as if he was dissipating the odor. This is a particularly evocative representation of pollution. It is also an unpleasant one, which might be a limit of this approach (see Section 5).C5: “it smells like cars”C2: “because there are more cars, because there are more humans”,

4.2. Reconfiguring Space

4.3. Making the Classroom Pervasive to Children’s Lives

4.3.1. Children’s Spatial Lives

4.3.2. Children’s Emotional and Social Lives

4.4. Opportunities for Citizenship Education

5. Perspectives and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Timeline of Design Iterations

Appendix B. Elements to Understand Meaning Construction during Field-Trips

| Time | 011831 | 011850 | 011854 | 011907 | 011928 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classroom setting | C2 interacts with the interactive map, assisted by teacher, C3 observes C2, others are seated, first author stands up | Idem | Idem | Idem, researcher introducing rubber as an olfactory resource to C1 | Idem, researcher presents the rubber to C3, which leads C1 and C3 to engage in a discussion |

| Speaker | C1 | First author | C1 | C1 | C1 |

| Utterance | “in Toulouse, there are services, a hospital and so on. In the countryside, there are no hospitals.” | “so what feels different in the city and the countryside?” | “space is reduced” | “What is that? Oooh it’s rubber” | “the pollution!” |

| Comment | He repeats a remark made earlier by the teacher | emphasis on “feels” (which in French is a synonym for smell) | - | - | - |

| Gestures | hands below the table | move around the classroom | - | - | points upward |

| Gaze | turns regularly towards and away his classmates | nothing in particular | - | - | follows the olfactory representation, turns towards C3 |

| Olfactory representation | - | - | - | - | rubber |

| Gustatory representation | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tangible representation | - | - | - | - | - |

Appendix C. Pedagogical Unit

Appendix C.1. Learning Objectives

- Themes. Describe, schematize and compare different types of human environments (e.g., urban, suburban or rural), and their organization (e.g., in terms of population, economical activities, or infrastructures); understand the different kinds of transportation infrastructures (local, regional, national);

- Skills. Developing the understanding of environmental cues; Map reading; following an itinerary; constructing the itinerary followed during a class trip; work collaboratively by formulating hypotheses and discuss them; Discover new technologies (the prototypes);

- Content. Learning about regional geography, especially the regional capital;

- More broadly, developing general culture and vocabulary, and fostering engagement with geography.

Appendix C.2. Organization

- First lesson. The first lesson was a field-trip. It focused primarily on developing the understanding of environmental cues and covered all the themes cited above.

- Second lesson. This lesson took place in the special education center. The children freely explored the tangibles designed for the pedagogical unit. The teacher reminded the children about the field trip. Pupils were then instructed to elaborate on hypotheses about what each tangible represented, before discussing these hypotheses with the rest of the class. The teacher provided cues when needed. These cues were of different types: associations with previously explored tangibles (e.g., “it is related to the one you’ve guessed before”), with previous class trips, or with everyday scenarios (e.g., “this is where you go when you have to send a letter”). This lesson was preparation for the third lesson and an occasion to discuss the themes again.

- Third lesson. The third lesson was conducted in the classroom and is described in this paper. It focused on synthesizing the elements to be acquired in the pedagogical unit.

Appendix D. Structure of the Activity

| Introduction | Eating a pastry, setting the goal: synthesizing the differences between human habitats and their reasons |

| Body | Smelling grass and eating strawberries |

| Discovery of the map | |

| Associating the three smellables/tastables with different areas of the map | |

| Finding different types of roads on the map | |

| Discussing the transportation infrastructure (e.g., national/regional roads) | |

| Discussing the transportation infrastructure (national/regional roads; canals) | |

| Smelling rubber | |

| Discussing pollution and its causes | |

| Synthesizing differences between farming and industry, countryside and cities | |

| Discussing the evolutions of work and how they shape cities | |

| Discussing the evolutions of work and how they shape cities | |

| Smelling colza and cheese (returning to the village) | |

| Synthesizing the similarities of structures between all habitats, starting by the village (e.g., church, town hall) | |

| Licking an envelope | |

| Discussing communication services (introducing the term infrastructure) through the example of postal services | |

| Conclusion | Synthesis the concepts learned, asking pupils for feedback on the lesson |

References

- Firth, R. Teaching Geography 11–18: A Conceptual Approach. Curric. J. 2011, 22, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catling, S. Children’s Personal Geographies and the English Primary School Geography Curriculum. Child. Geogr. 2005, 3, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersmehl, P. Teaching Geography; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt, J.; Storksdieck, M. A Short Review of School Field Trips: Key Findings from the Past and Implications for the Future. Visit. Stud. 2008, 11, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahenbuhl, K. Collaborative Field Trips: An Opportunity to Connect Practice With Pedagogy. Geogr. Teach. 2014, 11, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.; Jenkins, A. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory and Its Application in Geography in Higher Education. J. Geogr. 2000, 99, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, D. Sound and the Geographer. Geography 1989, 74, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.E. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. Geography and Landscape Science. Belgeo Revue Belge de GéOgraphie 2000, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, F. Situated Knowledge and Visual Education: Patrick Geddes and Reclus’s Geography (1886–1932). J. Geogr. 2017, 116, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P. Thinking geographically. Geogr.-Lond. 2006, 91, 199. [Google Scholar]

- Briand, M. Geography School Teaching through the Prism of School Outings: For an Approach by Means of Sensitiveness at Primary School. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Caen Basse-Normandie, Caen, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brulé, E.; Bailly, G. Taking into Account Sensory Knowledge: The Case of Geo-techologies for Children with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 236:1–236:14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, B.J.; McDaniel, M.A. Memory for Odors and Odor Names: Modalities of Elaboration and Imagery. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cognit. 1990, 16, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, N.; Lee, B.; Qiao, Y.; Muntean, G.M. Olfaction-enhanced multimedia: A survey of application domains, displays, and research challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2016, 48, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, E.P. The Specific Characteristics of the Sense of Smell. In Olfaction, Taste, and Cognition; Rouby, C., Schaal, B., Dubois, D., Gervais, R., Holley, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Quercia, D.; Schifanella, R.; Aiello, L.M.; McLean, K. Smelly Maps: The Digital Life of Urban Smellscapes. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Oxford, UK, 26–29 May 2015; pp. 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaud, J.P. A sonic paradigm of urban ambiances. J. Sonic Stud. 2011, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, M.; Nolan, J. Situating Olfactory Literacies: An Intersensory Pedagogy by Design. In Designing with Smell: Practices, Techniques and Challenges; Henshaw, V., Medway, D., Perkins, C., Warnaby, G., McLean, K.C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, C. The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Coffield, F.; Moseley, D.; Hall, E.; Ecclecstone, K. A Critical Analysis of Learning Styles and Pedagogy in Post-16 Learning: A Systematic and Critical Review; Technical Report; Learning and Skills Research Centre: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Husmann, P.R.; O’Loughlin, V.D. Another nail in the coffin for learning styles? Disparities among undergraduate anatomy students’ study strategies, class performance, and reported VARK learning styles. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, R.; Jonas, W. Case transfer: A design approach by artifacts and projection. Des. Issues 2010, 26, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulé, E.; Bailly, G.; Gentes, A. Identifying the Needs of Children Living with Visual Impairment: State of the Art and French Field-study. In Proceedings of the 27th Conference on L’Interaction Homme-Machine, Toulouse, France, 27–30 October 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 11:1–11:10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brule, E.; Bailly, G.; Brock, A.; Valentin, F.; Denis, G.; Jouffrais, C. MapSense: Multi-Sensory Interactive Maps for Children Living with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druin, A. The Role of Children in the Design of New Technology. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2002, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, A.M.; Truillet, P.; Oriola, B.; Picard, D.; Jouffrais, C. Interactivity Improves Usability of Geographic Maps for Visually Impaired People. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2015, 30, 156–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.; Sheridan, J.G.; Falcao, T.P.; Roussos, G. Towards a framework for investigating tangible environments for learning. Int. J. Arts Technol. 2008, 1, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauenberger, C.; Rauhala, M.; Fitzpatrick, G. In-Action Ethics. Interact. Comput. 2017, 29, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.; Powell, M.; Taylor, N.; Anderson, D.; Fitzgerald, R. Ethical Research Involving Children; UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti: Florence, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale. Socle Commun de Connaissances, de Compétences et de Culture. 2015. Available online: http://www.education.gouv.fr/pid285/bulletin_officiel.html?cid_bo=87834 (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Jewitt, C. Multimodal Methods for Researching Digital Technologies. In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Technology Research; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 250–265. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K.S.; Delgado, C.; Birr Moje, E. An Integrative Framework for the Analysis of Multiple and Multimodal Representations for Meaning-Making in Science Education. Sci. Educ. 2014, 98, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndyke, P.W.; Hayes-Roth, B. Differences in spatial knowledge acquired from maps and navigation. Cognit. Psychol. 1982, 14, 560–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthers, D.D. Technology Affordances for Intersubjective Meaning Making: A Research Agenda for CSCL. Int. J. Comput.-Support. Collab. Learn. 2006, 1, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, M.; Sassi, F. Social inequalities in obesity and overweight in 11 OECD countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2011, 23, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilmers, A.; Hilmers, D.C.; Dave, J. Neighborhood disparities in access to healthy foods and their effects on environmental justice. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1644–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuan, Y.F. Thought and Landscape: The Eye and the Mind’s Eye. In The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, A.H.; Manstead, A.S.; Zaalberg, R. Social influences on the emotion process. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 14, 171–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.Y.; Gilligan, C. When Boys Become Boys: Development, Relationships, and Masculinity; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cousteau, L. ABCD de l’égalité: Benoît Hamon n’avait Pas Le Choix. Available online: https://www.lexpress.fr/education/abcd-de-l-egalite-benoit-hamon-n-avait-pas-le-choix_1554708.html (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Borsari, A.; Brulé, E. Le sensible comme projet: Regards croisés. Hermès La Revue 2016, 1, 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, E. How to Bake Pi: An Edible Exploration of the Mathematics of Mathematics; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rowat, A.C.; Sinha, N.N.; Sörensen, P.M.; Campàs, O.; Castells, P.; Rosenberg, D.; Brenner, M.P.; Weitz, D.A. The kitchen as a physics classroom. Phys. Educ. 2014, 49, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metatla, O.; Serrano, M.; Jouffrais, C.; Thieme, A.; Kane, S.; Branham, S.; Brulé, É.; Bennett, C.L. Inclusive Education Technologies: Emerging Opportunities for People with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; p. W13. [Google Scholar]

| Id | Gender | Age | Grade | Impairments | SES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | M | 10 | 3rd grade | Blindness with light perception, motor, memory difficulties and psychological impairment | Disadvantaged |

| C2 | M | 11 | 5th grade | Blindness with light perception | Disadvantaged |

| C3 | M | 11 | 5th grade | Severe visual impairment and dyslexia | Middle class |

| C4 | M | 10 | 4th grade | Severe visual and hearing impairment | Advantaged |

| C5 | M | 11 | 4th grade | Blindness with light perception, multiple learning difficulties | Disadvantaged |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brulé, E.; Bailly, G.; Brock, A.; Gentès, A.; Jouffrais, C. An Exploratory Study of the Uses of a Multisensory Map—With Visually Impaired Children. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2018, 2, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030036

Brulé E, Bailly G, Brock A, Gentès A, Jouffrais C. An Exploratory Study of the Uses of a Multisensory Map—With Visually Impaired Children. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2018; 2(3):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030036

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrulé, Emeline, Gilles Bailly, Anke Brock, Annie Gentès, and Christophe Jouffrais. 2018. "An Exploratory Study of the Uses of a Multisensory Map—With Visually Impaired Children" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2, no. 3: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030036

APA StyleBrulé, E., Bailly, G., Brock, A., Gentès, A., & Jouffrais, C. (2018). An Exploratory Study of the Uses of a Multisensory Map—With Visually Impaired Children. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 2(3), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti2030036