1. Introduction

A city represents a holistic spatial system in which places and parcels are interconnected within functional chains and networks that are balanced, for instance through green infrastructure elements and structures [

1]. However, a city has been shaped throughout various periods and phases, during which several external disturbances have led to the emergence of gaps in the urban fabric that may in a later phase begin to exist and function independently [

2]. Empty spaces always emerge following a retreat from organization, leading to a re-evaluation of areas in cities that have been neglected for many years. They may also result from anthropogenic disturbances, such as war destruction or through natural disasters, such as earthquakes [

3], where informal and ephemeral uses fill the gap for a particular period of time. The devastation from wars and earthquakes can also deeply impact urban landscapes. Such external forces have the potential to destabilize the complex social, political, and economic structures that define a city’s identity. Widespread destruction of the physical environment can lead to the collapse of social structures, creating long-lasting psychosocial and economic challenges for affected populations [

4].

As cities face growing vulnerability to catastrophic events, prioritizing disaster resilience and urban sustainability has become more urgent than ever. Rapid urbanization and population growth in high-risk areas increase the scale of damage inflicted by natural disasters every year [

5].

In every city or urbanized environment, there are places that society does not utilize; such places are referred to by various names due to their lack of a clear or precise definition. By their nature, they provide the observer or visitor with the freedom and space for creative interpretation of these areas [

6].

Lost places often are undesirable urban areas without clear function or use that urgently require redesign. They generate less positive values than they have potential for and offer less benefits to their surroundings or users than they could [

7]. In urbanism, they are undefined, lacking measurable boundaries and communication routes [

8]. In the post-industrial landscapes of Central Europe, the convergence of ecological degradation and spatial neglect has given rise to new forms of landscape thinking.

Lost places and wetlands frequently exist at various thresholds—ecological, spatial, and temporal—disrupting normative assumptions about stability, aesthetics, and functionality within the urban environment [

9].

These spaces are characterized by conceptually flawed intentions—improper placement, neglected or abandoned areas, and dilapidated sites. Modern cities, particularly those rebuilt after 1950, focused primarily on the construction of buildings and residential districts, thereby isolating the surrounding landscape. This led to the emergence of lost places [

8]. In the context of Central European region, the legacy of socialist urbanization, industrial transformation, and shifting land-use regimes has produced a mosaic of neglected, underutilized, or forgotten spaces. These include infrastructural voids, post-agricultural margins, and peripheral green belts—many of which are increasingly subject to spontaneous rewilding, seasonal flooding, or vegetative succession [

6].

Sustainable urban development has become an increasingly pressing issue in response to the rapid pace of urbanization and the intensifying impact of climate change. A central element in addressing this challenge is integrating lost green spaces and urban wetlands into the framework of urban planning and design [

10]. These “forgotten spaces” can provide valuable ecosystem services—such as stormwater management, climate regulation, and habitat preservation—when thoughtfully incorporated into urban planning and design. Urban areas support many aquatic environments, including remnant or modified versions of aquatic systems that existed prior to human settlement, and systems deliberately created or designed to serve a specific purpose [

11]. In contrast, “accidental” urban wetlands are not the result of deliberate construction, nor are they remnant and/or modified environments that existed before human development. Instead, they form as the unplanned result of human activity in the landscape. As with created or remnant systems, accidental ecosystems have many structural elements (organismal, hydrological) that mimic natural, unaltered aquatic ecosystems [

9]. Modified urban aquatic systems are still capable of performing useful functions [

10] that include nutrient processing and removal [

12], the provision of habitat for key organisms [

13] and carbon sequestration and hydrologic functions such as cooling and groundwater recharge [

14].

Recognizing the role of these spaces in promoting urban sustainability allows planners to pursue innovative solutions that leverage their intrinsic ecological value [

11]. With urban expansion putting mounting pressure on natural resources, the need to safeguard and revitalize these neglected spaces has become more critical. Bringing lost green spaces and urban wetlands back into the urban environment can help counteract the negative impacts of land development, reinforce ecosystem functionality, and bolster the resilience of urban systems [

2]. Beyond ecological advantages, reestablishing people’s connection to nature through restoring forgotten spaces can have profound social and psychological effects. Engaging with green spaces and natural surroundings has been shown to enhance well-being, productivity, and overall quality of life [

6]. The conceptual landscape of these spaces is highly diverse. Marc Augé’s notion of “non-places” [

15] describes anthropological spaces of transience and anonymity, which lack historical significance or the capacity to foster social identity. These differ from Roger Trancik’s concept of “lost spaces” [

8], which are more directly the result of failures in urban planning or the neglect of the physical environment, whereas “non-places” are defined by an absence of relational “lost spaces”, referring to physically underutilized or derelict areas embedded within the urban fabric.

“Non-places” refer to anthropological spaces of ephemerality, where human beings remain anonymous and that lack sufficient significance to be categorized as public spaces. They possess no historically significant character and do not foster social or cultural identity [

16]. This term is a neologism that characterizes anthropological spaces of transience, where individuals remain anonymous, and the very nature of the place lacks the necessary qualities to be considered a true place [

7]. We perceive “non-places” as spaces through which individuals merely pass. In contrast, places possess a stable and organized form, transforming into spaces for habitation or interaction. Unlike non-places, which are primarily utilized as transit points or refuges for wildlife, debris, or vegetation [

15], forgotten places emerge as a result of the continuous expansion of cities into rural areas and a reluctance to care for the heritage and history of urbanized landscapes [

8]. As cities expand, forgotten gaps appear in the urban environment, which do not connect with the surrounding landscape and communicate with it only through engineering networks or transport infrastructure [

6]. In certain cases, such processes give rise to informal wetland ecologies—unplanned yet ecologically significant systems that emerge in the absence of human intervention [

16].

These are places that are not maintained and exist independently, creating new formations and natural phenomena directly within the city agglomeration. Anthropogenic nature holds partial scientific value in the context of a metropolis; however, it signifies an untapped potential for chaos and disorder [

2]. Often, we find inundated areas that transition into unorganized seasonal wetlands. The planning answer to undefined and hardly buildable sites, e.g., along railway lines or in flooding zones of rivers [

17], has varied throughout the intensification of urbanization in the 20th century. One common approach was establishing allotment gardens and garden colonies [

18]. In Mediterranean countries, it is common that local communities spontaneously overtake lost places and introduce a new, mostly informal, unofficial, and temporary use such as community gardens [

19]. This phenomenon is widely referred to as squatting or squat farming/gardening [

20].

This phenomenon describes the problem that investors no longer care about the landscape and prefer to build in new locations rather than attempting to revitalize or transform existing urban structures. Thus, in the so-called technological landscape, we often find ourselves trapped [

21]. We are increasingly surrounded by buildings that have lost their purpose—falling into disrepair—while just a few meters away, new structures are being erected. Such an approach prevents the city from forming a functional whole and instead fills the territory with emptiness [

21]. In addition to being valuable habitats, wetlands offer highly appealing recreational landscapes. Their ecosystem functions, services, and benefits can significantly enhance the visual appeal and environmental quality of urban areas. The importance of wetlands is closely linked to their ecosystem roles, which are equally vital for human communities [

20]. Their presence in the landscape is sustained by water, which carries socio-economic significance for the environment and offers numerous options for both active and passive recreation in various forms [

22].

Accidental wetlands exhibit characteristics of novel eco-systems [

9]. Given that these systems form in areas previously or currently under urban development, their soils and hydrology often differ greatly from native wetland systems in the same region [

23]. Geomorphic alterations such as ditching, berms, and waste dumps are common in urban landscapes, and contribute to high variability in soil surface elevation and water tables in urban wetlands and watersheds [

24].

The expansion of cities has favored the development of built environments over the preservation of natural ecosystems, particularly wetlands and green spaces, which were deemed less economically viable. The growing challenges associated with climate change—such as increased flooding, rising temperatures, and loss of biodiversity—have underscored the importance of these natural spaces within urban landscapes. Wetlands serve as natural buffers against flooding, regulate water cycles, and provide habitats for diverse species. Similarly, green spaces offer essential ecosystem services, including air purification, carbon sequestration, and temperature regulation [

25]. Wetlands provide a wide range of essential ecosystem services: they regulate water supplies, reduce the risks of flooding and storms, and support diverse plant and animal life [

26]. Recognition by municipalities of the benefits of integrating or preserving green space with minimal infra-structure will be critical for sustaining the services that many wetlands provide, including accidental wetlands. Little is known about how management intention or intervention influences most wetland functions, as compared to no intention or intervention [

9]. Additionally, urban wetlands will likely be highly dynamic in their characteristics and performance over time, as urbanization and climate change progress. Increased flooding in coastal cities due to urbanization and sea level rise could facilitate, for example, the formation of additional accidental wetlands, but could also result in the loss of remnant and constructed wetlands, or changes in wetland function as former freshwater systems become brackish [

27]. Abandoned and degraded urban spaces such as brownfields, disused industrial sites, or neglected urban fringes are often situated in low-lying or waterlogged areas [

24]. These locations offer significant potential for transformation into urban or peri-urban wetlands, functioning as ecosystem filters, water retention systems, and biodiversity refugia [

28].

However, urban expansion into these fragile ecosystems frequently disrupts these invaluable services, often with disproportionate impacts on the most vulnerable populations [

25]. Despite these crucial functions, many cities have failed to protect or even recognize these areas in urban plans, leading to their degradation or complete loss [

26]. The allure for these forgotten places can be precisely determined by their newly chosen functions, roles, and meanings [

8].

2. Identification of Urban Forgotten Spaces

Following the identification of urban forgotten spaces, individual areas were further categorized based on their functional attributes and their potential for future development. This theoretical reflection aims to reframe such “lost spaces” not as obsolete or wasted, but as productive ecotones that challenge conventional notions of landscape value, function, and authorship. At the same time, this paper proposes a conceptual framework in which wetlands and abandoned spaces are understood not as residual categories within planning, urbanism, or ecology, but as sites primed for interdisciplinary investigation and new forms of interaction.

The objective was to investigate the sources of dissatisfaction observed during the occupancy phase and to develop new design objectives that would meet user needs and enhance the space’s functionality. The quality of space and user satisfaction can be ensured by improving its efficiency.

An extensive literature review was conducted, based on retrieved definitions and terminology related to forgotten spaces, non places, and lost places, incorporating studies focused on the regenerative and intervention aspects of such spaces.

Observations were carried out across a series of urban environments exhibiting various degrees of ecological degradation, infrastructure density, and vulnerability to anthropogenic and natural disturbances. Sites were selected according to predefined criteria, such as evidence of fragmentation within the urban landscape, the presence of “lost” or “forgotten” green areas, proximity to transit networks, and historical exposure to disasters (whether natural or war-related).

2.1. Literature Search and Selection Criteria

An extensive systematic literature review was conducted based on identified definitions and terminology related to forgotten spaces. The search was carried out in the Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases using the keywords: Abandoned Areas, Abandonment, Accidental urban wetlands, Anxious Landscape, Antispaces, Dead Space, Drosscape, Forgotten Space, Leftover space, Lost Spaces, Non-Places, Of Other Spaces: Heterotopias, Opaque Terrain, Places Between Places, Residual space, Subnature, Terrain Vague, The Blind Spot of Urbanism, The Other City, The Third Landscape, Urban Gaps, Urban Jungle, Urban Voids, and Urban Wilderness. Studies addressing regenerative and interventionist approaches to these spaces were also included in the analysis. The search was limited to publications released between 1960 and 2025. Inclusion criteria required that the works examine urban or peri-urban contexts, reflect ecological or social dimensions, and comprise peer-reviewed journal articles, monographs, or conference proceedings. Exclusion criteria encompassed purely technical reports, studies lacking methodological transparency, or texts that did not explicitly address the spatial aspects of forgotten spaces.

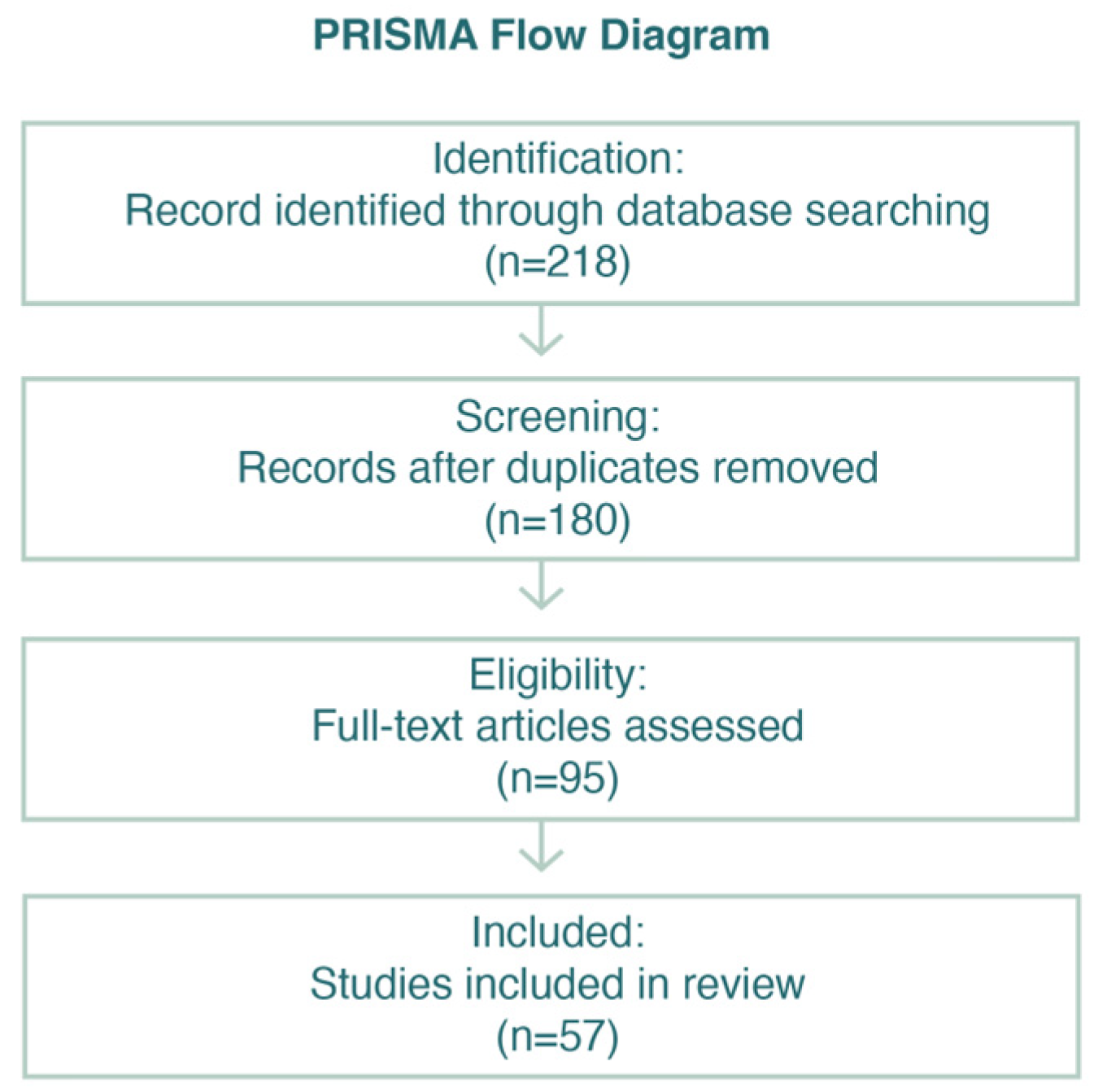

In total, 218 records were identified. After removing 38 duplicates, 180 unique records remained for the screening phase. Based on title and abstract assessment, 85 studies were excluded for failing to meet the thematic focus or being limited to technical and engineering perspectives without ecological or social relevance. Ninety-five publications proceeded to full-text evaluation, of which thirty-eight were excluded due to a lack of comparative assessment (n = 12), methodological opacity (n = 9), or irrelevance to spatial, ecological, or social dimensions (n = 17). Ultimately, 57 studies met all inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the systematic review.

The entire selection process, illustrated in the PRISMA diagram, see

Figure 1.

2.2. Urban Public Places

Within the broader typology of forgotten urban spaces, public spaces constitute a distinct and methodologically relevant category. These include neglected squares, abandoned courtyards, underused pedestrian zones, and residual land between infrastructure systems. Despite often being overlooked, such spaces possess both symbolic and functional value, offering potential for social activation, ecological reintegration, and community-driven transformation. Their inclusion in the analytical framework is based on their accessibility and visibility, as well as their capacity to serve as platforms for participatory placemaking processes. By recognizing these spaces as latent connectors within the urban fabric, the methodology expands the scope of transformation beyond ecological restoration to include social cohesion, cultural identity, and inclusive urban regeneration.

Lost and Abandoned Spaces in Landscape Theory

The concept of the “lost space” emerged in urban and landscape discourse as a critique of the functionalist planning paradigms that dominated the 20th century.

Lost space defines such spaces as “anti-spaces”—residual, fragmented, and often degraded urban areas resulting from a lack of spatial integration or coherent design [

8]. These include infrastructural voids, derelict industrial zones, and neglected interstitial zones at the edges of planned development. While these sites were historically considered as urban failures or blight, recent theoretical developments have reinterpreted them as potentially generative terrains [

21].

The notion of terrain vague, introduced by de Solà-Morales, further nuanced this discussion by emphasizing the ambiguity and openness of abandoned spaces. These sites resist fixed identity or function; they are perceived not just as spatial leftovers, but as symbolically charged voids, open to reinterpretation and transformation [

29]. Their marginality, in this sense, becomes their value—an invitation to rethink spatial order, temporality, and ecological presence. In the Central European context, particularly in Slovakia and other post-socialist states, such spaces are widespread due to the rapid deindustrialization and land reform processes of the 1990s [

29]. The fall of state-controlled planning systems led to fragmented land ownership, disinvestment in infrastructure, and a proliferation of urban and rural in-between spaces [

30]. These zones, see

Table 1, are often legally unresolved, socially overlooked, and ecologically unstable—yet they are precisely where spontaneous processes of natural recovery and wetland emergence are now visible.

2.3. Methods for Identifying Forgotten Spaces

Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody [

21]. Placemaking is a collaborative process with the community to redefine public spaces [

6]. It enforces the connection between people and place. To make a place have better urban design is not a priority; rather, providing a wide range of activities and incorporating physical, cultural, and social identities that define a place are the primary objectives [

15]. Placemaking is a continuous process and evolves over time.

The relationships between forgotten spaces and the city are analyzed from physical, social, and economic perspectives to determine the role such spaces play in the city and how they may function as fully integrated public spaces, see

Table 2. Urban forgotten spaces come in various forms, name, sizes, ranging from small, neglected land remnants left untended and forgotten wetlands to large, abandoned ruins in city centers. These spaces are categorized into organized forgotten spaces and unorganized forgotten spaces. Alongside the creation of residential areas, all sites included in the working database can be evaluated and compared, with their immediate surroundings assessed through comparative research methods. Data were gathered using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to capture the ecological, social, and spatial dynamics of neglected urban spaces.

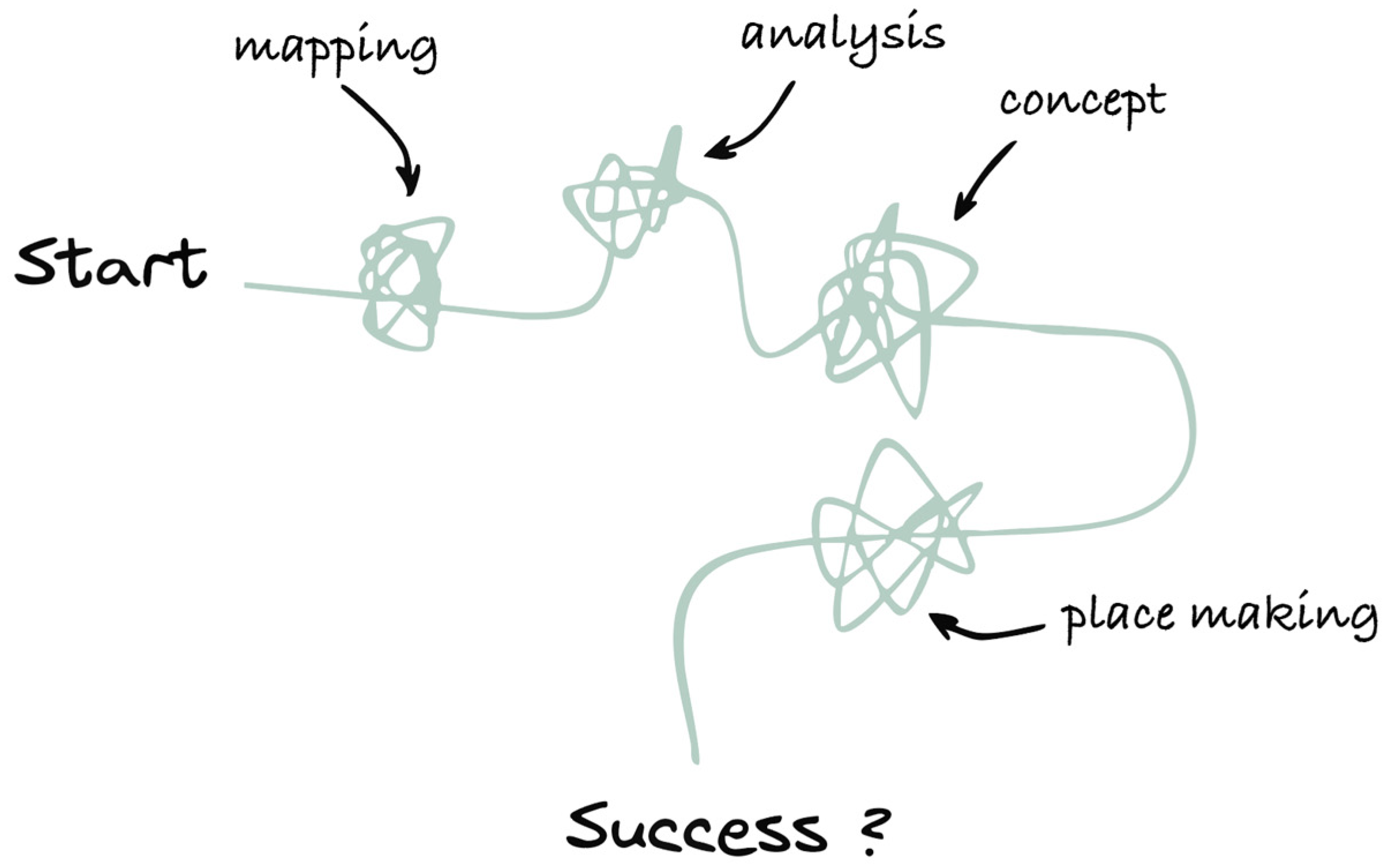

2.4. Phases of Spatial Analysis and Design Interpretation

Mapping: This initial phase involves the identification and documentation of neglected urban spaces using GIS tools, on-site observations, and historical map research. The aim is to understand their spatial distribution and temporal evolution.

Analysis: A detailed examination follows, focusing on spatial, ecological, social, and functional attributes of each site. This stage reveals both the hidden potential and the inherent limitations that must be considered in future planning.

Conceptualization: This step entails a theoretical classification of the identified spaces—for example, distinguishing between organized and unorganized forgotten spaces—and considers their potential contributions to urban regeneration processes.

Place-Making: The final phase explores possible interventions that holistically integrate cultural, social, and ecological dimensions. The goal is to transform overlooked spaces into valuable and meaningful elements of the urban space, see

Figure 2.

2.5. Impact of Urbanization on Wetland Biodiversity

Fragmentation of wetland habitats caused by urbanization can negatively impact native flora and fauna, resulting in shifts in species diversity, distribution patterns, population structure, and overall ecosystem function. Wetlands are natural or artificially created ecosystems located at the transitional zone between terrestrial and aquatic environments. They are typically characterized by permanently or temporarily elevated groundwater levels or periodic flooding, which create specific conditions conducive to the presence of hydrophilic vegetation and hydric soils [

9]. This occurs because changes in land use associated with urbanization often lead to a decrease in available habitat for plants and animals, increased habitat fragmentation, and overall decline in environmental quality [

3]. Additionally, the expansion of boundary habitats and related edge effects can limit the spread of pollen and seeds, increasing the number of soil patches vulnerable to invasive species and facilitating species invasions. The reduction and loss of biodiversity will critically impact the stability and ecological balance of wetland ecosystems, deteriorate soil fertility and water quality, affect food supplies as well as industrial and agricultural resources, and ultimately threaten ecological security and sustainable human development [

18].

Wetlands as Liminal Landscapes

Wetlands are, by their very nature, liminal landscapes—positioned between terrestrial and aquatic realms. Ecologically, they serve as buffers, filters, and transition zones, enabling nutrient cycling, biodiversity maintenance, and water regulation. However, their cultural and spatial marginality has long been embedded in planning and land-use discourses. In many parts of Europe, wetlands were historically viewed as undesirable, unhealthy, or economically unproductive, leading to widespread drainage, infill, and conversion into farmland or development zones [

9].

Within landscape theory, however, wetlands have reemerged as critical spaces of resilience, hybridity, and renewal. We embody the processual and dynamic nature of landscape—one that resists rigid categorization or control [

11]. Wetlands are not static landforms but living systems, shaped by hydrological fluctuation, climatic variability, and multi-species interactions [

14].

3. Results

The research will explore innovative approaches for future use of these spaces, primarily through graphic representations. These areas display unique, non-urban characteristics, despite not being fully developed public spaces. They are marked by disorder, random vegetation, unattractiveness, and neglect, litter is commonly found, and they lack dominant architecture or specific vegetation. Transform these places into aesthetically pleasing, organized spaces, bringing structure and offering them to residents as recreational areas. Redesigned public spaces offer more than just aesthetic or ecological value—they serve as vital nodes for community well-being. When formerly neglected or undefined urban voids are reimagined for public use, they support physical and mental health by encouraging outdoor activity, social interaction, and relaxation. These spaces become especially important for vulnerable or underserved groups, such as children, the elderly, and people with disabilities, by providing accessible, inclusive environments that foster a sense of belonging. By integrating flexible, multi-functional elements tailored to various age groups and cultural contexts, such public spaces can act as intergenerational and intercultural meeting points, contributing to stronger social cohesion and resilience within urban communities.

We systematically categorized the potential applications and described them in terms of their positive environmental impact, as they represent an initial step toward improving the selected areas. Based on the placement of these applications, further categorization of the space is possible, allowing additional elements to be incorporated during landscape or architectural design interventions. In structured passageways or inner courtyards, it is essential to rediscover functionality and ensure these places are accessible and available to the public. That urban voids offer habitats for a variety of plants and animals, enriching urban biodiversity.

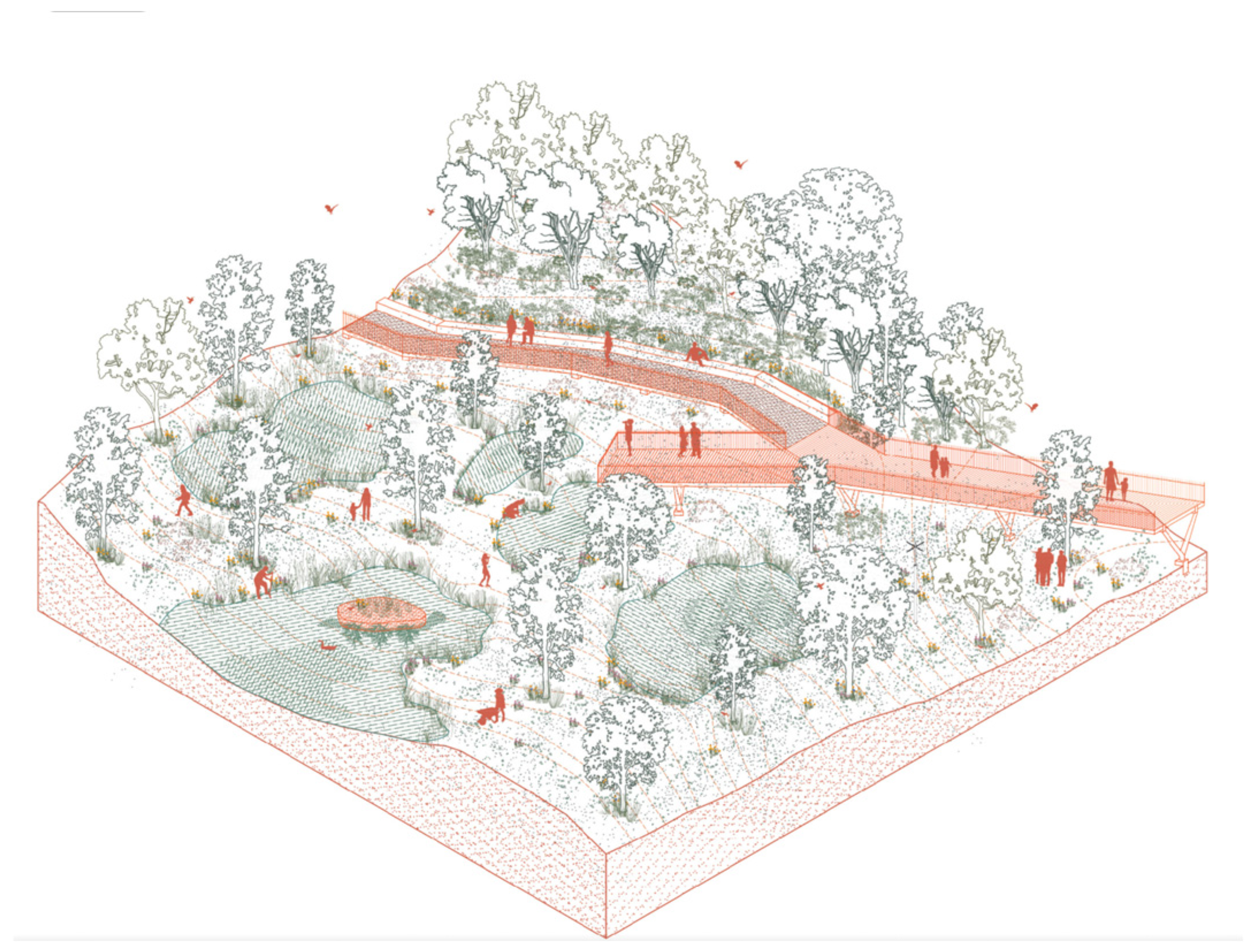

3.1. Strategy Design Tactics

The focus of this inquiry is the relationship between urban voids and public spaces. The aim is to examine how these neglected or underutilized areas can be reimagined and transformed into functional public spaces that address the needs of residents, foster social interactions, and contribute to the overall quality of the urban environment [

35]. A central aspect of this relationship lies in the potential of such voids to shift from overlooked zones into valuable and active components of the urban structure of the city. The relationship between constructs and dimensions explores how urban voids can be effectively transformed into functional public spaces, see

Figure 3.

3.1.1. Void Transformation

The redesigned structure transforms the urban room, which for decades has been little more than a neglected space used for parking and debris. For the first time in history, it provides shelter from the dynamic environment, offering the community a space for relaxation and leisure, while also becoming a symbol that captures the collective imagination [

35], see

Figure 4.

Moreover, in low-traffic areas, the natural growth of vegetation (ruderal species) adds biodiversity, which can be particularly beneficial for urban ecology. The research suggests that redesigning these spaces as multifunctional areas can help cities move toward sustainable futures by fostering human-nature interactions, improving ecological stability, and mitigating some negative impacts of urban expansion, see

Figure 5.

Figure 4 is an example of design strategy for transforming a specific type of urban space—such as a low-traffic area with spontaneous natural growth, a lost or abandoned site, or an accidental wetland—into a functional ecological system. The newly introduced spatial structure assign’s identity to the formerly forgotten space, allowing it to serve both ecological and social functions. The new structure gives identity to the forgotten space.

3.1.2. Wetland Transformation Strategy

Transforming and updating such spaces requires an understanding of the dynamic, living nature of our communities. The balance between open spaces and structures, private and public areas, and individualism and social interaction shifts over time. We are entering a new era in which urban planning must prioritize human health and well-being, along with planetary factors [

20]. In areas with minimal traffic, ruderal vegetation flourishes, contributing to greater biodiversity [

21].

As part of design strategy, a shade was proposed with linear wall of the site, which acts as a datum that gives the open space a shape. It was imagined as a place that holds many events, programs, and a public life incubator for the future. The shading work was a powerful tool to activate the residue space with programs and activities [

48]. Furthermore, the ecological potential of these voids extends beyond ruderal vegetation. Studies suggest that when designed appropriately, these areas can support a surprising range of urban wildlife, including pollinators, birds, and small mammals, contributing to the creation of micro-habitats within the dense urban fabric [

49]. The introduction of native plant species not only enhances biodiversity but also ensures greater resilience to climate stressors such as drought or heatwaves, which are increasingly relevant in contemporary urban planning [

24].

3.1.3. Application of Landscape Transformation

To provide a comprehensive understanding of various approaches to transforming underutilized urban spaces, five case studies were selected from different geographic and cultural contexts.

The first example,

Paley Park in Manhattan, New York, see

Figure 6, serves as an archetypal model of permanent urban infill public space. This project successfully transformed a former vacant lot—previously an urban void—into a pocket park that offers a high-quality, human-scaled retreat within the dense fabric of the city. Its enduring design provides permanent public access and amenities, proving that even small and constrained sites can become essential components of urban life. By converting an underutilized site into a vibrant green oasis, Paley Park revitalized the surrounding neighborhood, providing residents and workers with a welcoming place to relax, socialize, and escape the urban hustle. The introduction of natural elements and thoughtful design significantly enhanced the area’s livability. Exemplifies how careful spatial articulation, integration of water features, greenery, and seating can convert a residual space into a socially meaningful and psychologically accessible urban environment. It welcomes more than 500,000 visitors annually, which is approximately 60 people per hour. This number of visitors makes Paley Park the most used park in New York per square meter [

50].

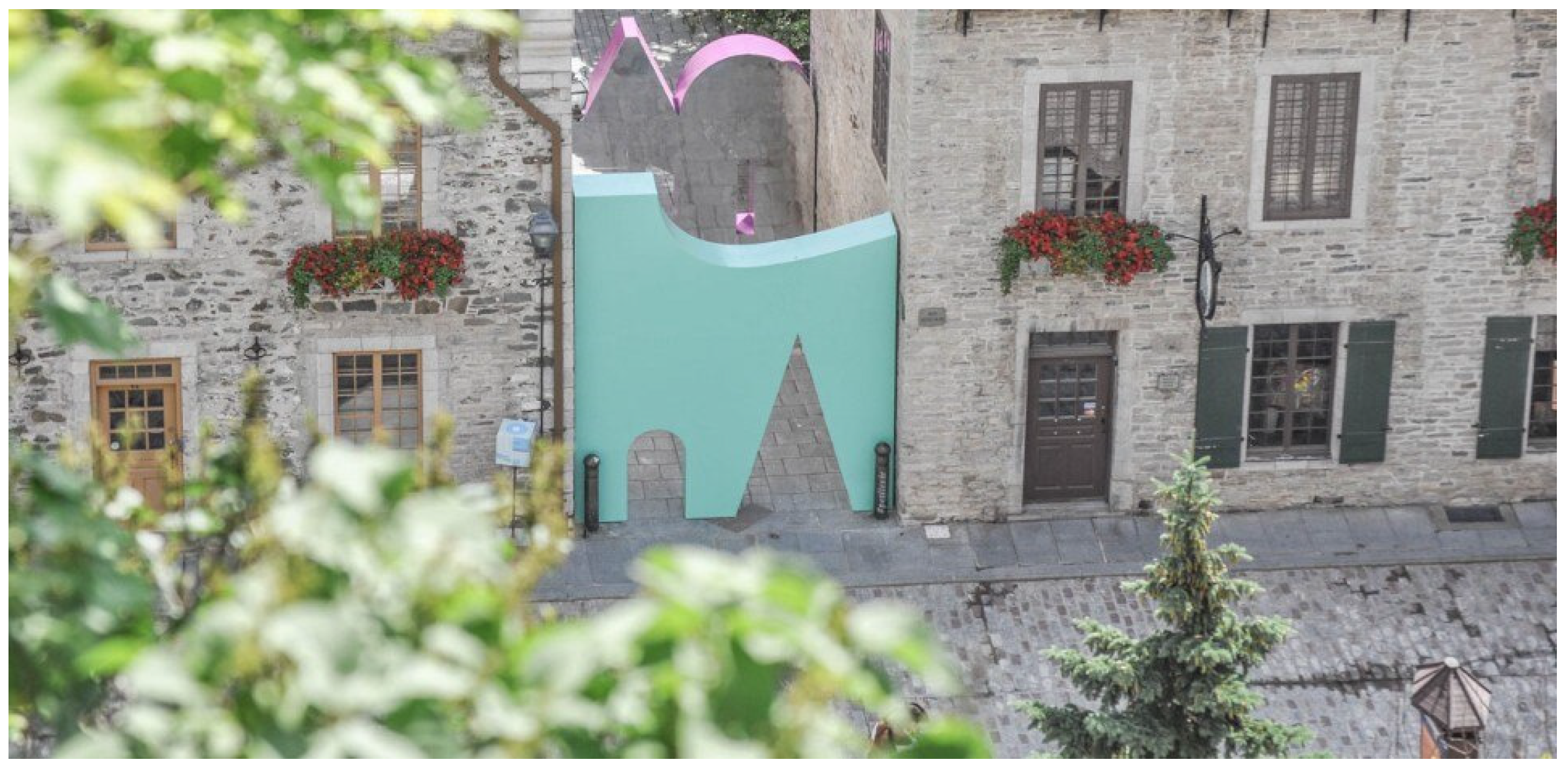

In contrast,

Petite Vie in Quebec, Canada, see

Figure 7, represents a temporary artistic intervention within an urban gap. This project emphasizes the use of ephemeral, site-specific art installations to activate neglected plots and stimulate public imagination. The installation functions as an agent of placemaking by inviting curiosity, gathering, and reflection, without requiring permanent physical transformation. The installation consists of colorful structures and artistic elements designed to activate the underused space and attract public attention. Such temporary artistic endeavors illustrate the capacity of creative practices to bridge the gap between urban voids and potential future uses, thereby challenging conventional notions of public space ownership, use, and temporality [

52]. These interventions also support community engagement by encouraging local participation and dialogue about the use and meaning of public spaces. The temporary nature allows for experimentation and innovation and provides valuable insights for future sustainable development and aesthetic perception of public space.

Mudroňova Street in Bratislava, Slovakia, see

Figure 8, is an example of tactical urbanism, applied to a lost or leftover space. This case study embodies the principles of low-cost, scalable, and community-driven interventions that serve as prototypes for long-term transformation. Tactical urbanism enables local stakeholders to experiment with new uses—such as pop-up public amenities, pedestrianization, or micro-installations—without committing to irreversible changes. These interventions had a positive impact on the neighborhood—more people started to meet and communicate, the space became safer thanks to better lighting and greater clarity, and people started to appreciate it more and feel like a place of their own. The temporary modifications attracted more pedestrians, which revived local traffic and helped to reawaken a forgotten part of the neighborhood. Temporary redesign employs modular seating, painted ground markings, and planters to test potential long-term improvements in walkability and public usability. This approach fosters public involvement and reveals the latent potential of forgotten urban interstices while addressing immediate spatial deficiencies [

54].

The project

Jardin du Tiers Paysage in Saint-Nazaire, France, see

Figure 9, offers a unique interpretation of urban transformation through the temporary ecological enrichment of a so-called “third landscape”. This conceptual framework, introduced by landscape theorist Gilles Clément, acknowledges the ecological value of unmanaged and spontaneous urban vegetation. Ruderal plant species were introduced to an abandoned site to promote biodiversity and spontaneous vegetation growth. The establishment and careful management of this “third landscape” enhanced local biodiversity by creating habitats for various flora and fauna that typically struggle to survive in highly managed urban environments. The minimal human intervention allowed natural ecological processes to flourish, fostering a resilient and self-sustaining ecosystem within the forgotten space. By deliberately encouraging ruderal plant growth and minimal human intervention, this project reframes neglected spaces as reservoirs of biodiversity, memory, and environmental resilience. Such interventions underscore the importance of integrating ecological processes into urban design and recognize the performative role of nature in shaping the urban environment over time [

31].

Finally,

The Xibei Lake Wetland in Wuhan, China, see

Figure 10, exemplifies a permanent ecological restoration of a formerly degraded wetland. As a large-scale environmental infrastructure project, this intervention reinstates the site’s ecological functions—such as water purification, habitat creation, and flood control—within the urban ecosystem. The restoration involved the revitalization of natural waterways, the reintroduction of native vegetation, and the removal of pollutants, which significantly enhanced habitat diversity and facilitated the return of numerous plant and animal species. This process also increased the appeal of the area, transforming it into a popular recreational space for residents. The project contributes to the long-term sustainability of the city by mitigating climate-related risks and enhancing urban biodiversity [

56]. Moreover, the restored wetland doubles as an educational and recreational landscape, demonstrating the multifunctionality of contemporary green infrastructure in cities facing rapid expansion and ecological stress [

57].

Collectively, these case studies reveal the wide spectrum of possibilities for the transformation of urban voids—from temporary artistic and tactical interventions to permanent ecological and spatial redesigns. They demonstrate that underutilized spaces are not fixed categories but dynamic entities with potential to serve multiple roles—social, ecological, aesthetic, and functional—depending on the adopted design strategy. This pluralism reflects an evolving understanding of public space in urban planning theory, where the boundaries between permanence and temporariness, nature and culture, or design and spontaneity are increasingly blurred. These examples represent a diverse range of spatial types, durations of intervention, and design strategies, see in

Table 3, highlighting the flexibility and adaptability of urban regeneration practices [

43].

4. Discussion

We do not attempt to define what cannot be named. As Thomas Sieverts [

35] states, “What is necessary in this situation of uncertainty… is the highest degree of openness” [

35]. Along similar lines, James Corner [

58] notes that “to name something is, to some extent, to claim it” [

48] while Sergio Lopez-Pineiro [

59] emphasizes that “to preserve space’s openness, marginality, and indeterminacy… it must remain unnamable” [

58]. Space must remain undisturbed until its intrinsic qualities are fully explored. Despite their diversity, these remnants share common traits, which is why many related concepts exist, each offering variations adapted to specific languages and locales.

Sieverts [

35] observed that “our contemporary view of urban development is shaped by the concept of uncertainty” [

60]. This uncertainty introduces potential and openness, allowing for numerous possibilities for analysis and intervention. “Uncertainty is understood as a ‘challenge,’ an adventure in urban development, a space that cannot be defined or fixed but can be shaped through the projection of an activating image and brought into a concrete ‘disposition.’ This space cannot be ‘functionally defined,’ but it can at least be imbued with a positive ‘mood,’ allowing it to be perceived as an open space of possibilities” [

59]. Given this expansive scope, it becomes challenging to delineate and present all the endless potential applications.

The distinction between “empty spaces” and “forgotten spaces” remains conceptually significant in contemporary urban studies, yet these terms are often used interchangeably in both scholarly discourse and practical urban planning.

“Empty spaces” are typically understood as deliberately unoccupied or underutilized areas within the urban fabric. Their emptiness is relative and context-dependent; such spaces may result from intentional urban design [

43] or from socio-economic processes such as depopulation or market shifts. Importantly, their “emptiness” often reflects potentiality—a latent capacity for future appropriation, transformation, or intervention. Thus, they are framed as sites of possibility, aligned with concepts such as “urban voids” or “terrain vague”, which scholars [

29] have interpreted as spaces offering opportunities for alternative, non-prescribed uses.

In contrast, “forgotten spaces” carry a distinct socio-cultural and temporal dimension. They are not merely unused but have slipped from the collective urban consciousness, neglected by planners, authorities, and sometimes even residents [

8]. These spaces often bear traces of past functions—industrial ruins, abandoned infrastructure, obsolete transport nodes—that mark them as relics of previous urban epochs. As such, they embody a form of urban memory, albeit one obscured or repressed, making their reactivation a culturally and politically charged process.

The natural ecology of wetlands and their design plays a pivotal role in restoring and reimagining neglected wetlands. Wetland ecosystems rely on the application of core ecological principles and methods to construct, restore, and adapt these environments in ways that preserve their essential functions while fostering sustainable ecosystem development [

19]. A deep understanding of vital ecosystem services—beyond terrestrial resources—is critical. These include urban safety protection, mitigating the urban heat island effect, disaster impact reduction, and wildlife conservation. For example, The Xibei Lake Wetland in Wuhan, China, highlights how permanent ecological restoration can transform degraded wetlands into valuable natural habitats that enhance urban resilience. However, there remains a notable lack of tools for integrating forgotten spaces, both in size and scope, into urban development. Institutional barriers frequently hinder progress. These include fragmented land ownership, outdated spatial regulations that fail to recognize the value of such “in-between spaces”, a lack of specialized financial mechanisms for their revitalization, and insufficient cross-sectoral coordination within local governments [

33]. These spaces are not being given the opportunities needed to support sustainable urban growth while minimizing land use. The objective is to transform urbanized wetlands into a holistic model of ecological security [

26]. Perceptions and values wetlands have long been perceived as undesirable, nuisance systems [

61] and vacant urban lots are not typically considered desirable or aesthetically pleasing. Many cities have ordinances mandating vacant lots be maintained by clipping “weeds” and draining water from the site (to reduce mosquito populations). Many urban dwellers may consider accidental wetlands to be unsightly, disease-breeding, garbage-collecting blights on the landscape, rather than viable ecosystems that provide important ecological and sociological services. However, some see them as areas for recreating, viewing wildlife, and observing local traditions or cultural activities [

62]. An important research need is to engage with people to determine their perceptions and values in terms of urban environments and the services they can provide. This may allow urban planners to help people living in cities use accidental wetlands more effectively, and could increase the perceived value of these environments [

9].

“The search for a balance between ecological restoration and the risk of gentrification remains a central challenge in the revitalization of forgotten spaces, which play a significant role in enhancing urban resilience to the impacts of climate change. Owing to their undefined and flexible character, these spaces enable spontaneous ecological processes such as natural succession, water retention, and the support of biodiversity. However, their valorization simultaneously creates pressures that may alter the social structure of the area and contribute to the displacement of original communities [

61]. Forgotten spaces, as a distinct category of urban voids, represent a unique potential for ecological renewal and for cities’ adaptations to changing climatic conditions. Their temporary disuse and lack of fixed functions allow for the spontaneous development of vegetation, the emergence of natural habitats, the improvement of microclimatic conditions, and the retention of rainwater—factors that significantly contribute to the enhancement of urban ecological resilience [

63]. At the same time, the ecological transformation of these areas brings the inherent risk of gentrification, which can lead to shifts in the social fabric of local communities and the displacement of long-term residents [

64]. The introduction of community gardens, green parks, or ecological corridors increases the attractiveness of such spaces on the real estate market, making them targets for speculative investment and development projects. This process may paradoxically reduce their original environmental and social value by eliminating their spontaneity, openness, and informality of use [

65]. Striking this balance is particularly crucial in the context of urban climate adaptation, where forgotten spaces may serve not only as key areas for the development of green-blue infrastructure but also as loci preserving the historical memory and identity of local communities.

We define forgotten spaces because these areas often represent untapped potential for community, ecological, and economic improvements [

32]. The effective utilization of all available urban spaces contributes to the reduction of urban sprawl, enhances quality of life, and supports the sustainability of cities [

56]. Forgotten spaces can be transformed into parks, community gardens, or public places, thereby fostering social cohesion and increasing urban biodiversity [

11]. Consequently, their identification and integration into urban planning strategies are essential for the healthy and efficient development of cities.

The utilization of all urban spaces is imperative due to the need for efficient management of limited urban resources and to prevent uncontrolled urban expansion (sprawl), which leads to environmental degradation and increased transportation costs [

66]. The preservation and integration of natural areas, such as wetlands, are crucial for flood risk management and for promoting biodiversity within urban environments [

61]. Moreover, optimizing the use of existing spaces contributes to the conservation of natural resources and biodiversity, which is vital for maintaining ecological balance in the urban context [

56].

Cities can only experiment on themselves, so why not use these ambiguous remnants to develop new strategies enabling spontaneous and diverse appropriation approaches [

60]? The goal would be to turn them into public spaces teeming with diversity, where ideas converge in an open arena of expression and interaction, akin to a public stage [

42].

5. Conclusions

Cities can only experiment on themselves, so why not leverage these forgotten spaces to craft new strategies that facilitate spontaneous and varied appropriation approaches? The aim is to transform them into public spaces rich in urban diversity, where ideas merge into a broader urbanism designed for public interaction. Additionally, a significant disparity persists in the recognition and utilization of forgotten spaces and wetlands in terms of their size and scope. There is a pressing need to create a framework that provides room for sustainable urban development while ensuring minimal effective land use, thus transforming urbanized wetlands into a comprehensive model of ecological security; a framework that provides room for sustainable urban development while ensuring effective land use. Ultimately, wetlands in abandoned spaces do not merely restore lost nature; they enact a liminal ecology of the Anthropocene, where landscape becomes a dialogic process of forgetting, remembering, and imagining new futures.

Urban development must remain focused on discovering more inclusive approaches that tackle urban challenges while expanding its dialogue with other disciplines. This involves formulating strategies that encourage direct community involvement to drive meaningful changes in areas where such transformations are possible. Interventions in neglected spaces could redefine the boundaries of urban dynamics, enhancing their capacity to benefit specific communities directly. These efforts should integrate community-led initiatives, eliminate negative perceptions, and allow for adaptive planning and use of these spaces.

This study has identified several key findings related to the conceptualization and transformation of urban voids. Commonly referred to as interstitial spaces, residual spaces, or terrain vague, urban voids are characterized by spatial fragmentation, marginality, and latent ecological or social potential. A typological framework was used to classify these voids, including abandoned lots, post-industrial lands, infrastructural remnants, and urban wetlands. Design interpretations include adaptive reuse, ecological restoration, and temporary or tactical interventions that respond to both environmental and social needs. Transformation strategies center on inclusive, bottom-up approaches that engage stakeholders and promote multifunctionality. Illustrative case studies demonstrate how such spaces can be reimagined into vibrant, inclusive, and ecologically resilient public realms. These findings support the development of integrated frameworks that combine community engagement, ecological sensitivity, and spatial innovation to guide future interventions in neglected urban landscapes.

A fundamental change in perception and shift in mindset is required, moving from viewing forgotten spaces as problems to recognizing them as opportunities for innovative urban greening. Finding the right balance between urban space type and transformation for environment, culture, social, and economic, including selecting a public space type, as compared to a green or blue space type.

Addressing systemic barriers: significant challenges persist in integrating these spaces into formal planning frameworks, largely due to institutional inertia, fragmented governance, and a lack of dedicated financial resources. Effective optimization of land use, particularly for urban wetlands aimed at ecological security, necessitates overcoming these systemic obstacles.

Strengthening collaboration between local governments and the non-profit or academic sectors is essential for unlocking the transformative potential of underutilized urban spaces. One effective mechanism is the establishment of “urban laboratories”—institutional platforms through which municipalities can engage in structured partnerships with universities, civic associations, and architectural professionals to co-develop pilot projects. A notable example is the Metropolitan Institute of Bratislava (MIB), which serves as a model for how such institutions can foster innovation in urban policy and design; similar frameworks could be replicated in other Slovak cities. Moreover, there is a critical need for the formal recognition of grassroots initiatives. Many bottom-up activities currently lack the legal infrastructure necessary to access public space or funding, thereby limiting their scalability and institutional legitimacy. Developing regulatory pathways that acknowledge and support these civic-driven processes would significantly enhance their capacity to contribute to inclusive urban regeneration. The identification of institutional barriers, including fragmented land ownership and outdated regulations, underscores the need for targeted policy instruments. Municipal and regional authorities should implement adaptive zoning regulations, promote land consolidation, and support green infrastructure initiatives, while fiscal incentives could encourage landowners to maintain vacant areas as ecological or community assets. Moreover, the establishment of governance mechanisms and participatory management models can facilitate the effective development of these spaces and concurrently enhance urban biodiversity.

Multidisciplinary stakeholders, including architects and artists, have the opportunity to design compelling, dynamic, and functional solutions that act as catalysts for change and public engagement. The key is uncovering these spaces. Forgotten places can be effectively transformed and imbued with added value by considering all stakeholders connected to the space and its surrounding context, developing tools tailored to their needs.

In future research, we intend to expand the scope of analysis by identifying and mapping forgotten green spaces and accidental urban wetlands across Slovak cities. Furthermore, we will explore international best practices for reactivating such spaces to support ecological resilience, biodiversity, and community well-being. This comparative approach will provide deeper insights into systemic challenges and potential opportunities for sustainable transformation.