1. Introduction

Cities play an increasingly central role in territorial development, acting as engines of economic growth, innovation, and social well-being [

1,

2,

3]. Since the Industrial Revolution, urban areas have become key loci for the concentration of productive activities, the circulation of goods and services, and the provision of essential infrastructures that support quality of life [

4,

5]. Furthermore, cities are privileged arenas for the formulation, experimentation, and implementation of public policies and governance models aimed at promoting sustainability and territorial cohesion [

6].

In recent decades, the transformation of urban territories has accelerated, driven by processes such as globalisation, digitalisation, and intensified urbanisation. These dynamics have contributed to a compression of space and acceleration of time [

4,

7], rendering urban life more fluid, complex, and volatile. As a result, urban planning and management face heightened challenges, including the need to respond more rapidly and flexibly to evolving social, environmental, and economic conditions [

8,

9].

Traditional urban issues, such as socio-spatial segregation, congestion, environmental degradation, and the overuse of natural resources, have been amplified by these transformations [

3,

10]. At the same time, new and interrelated challenges have emerged, notably the imperative to adapt cities to climate change, to incorporate digital technologies into urban governance, and to address new patterns of mobility, work, and time use [

2,

8]. Together, these factors highlight the urgent need for innovative planning strategies that can ensure the sustainability, resilience, and inclusivity of urban systems.

Among the various models proposed in response to these challenges, the “15-minute city”, a concept introduced by Moreno, has garnered international attention [

11,

12]. This model advocates for a reorganisation of urban space based on proximity, proposing that essential daily functions (housing, employment, commerce, healthcare, education, and leisure) should be accessible within a 15-minute walk or cycle from home. By reducing the need for long commutes, the model aims to restore quality time to residents, foster active mobility, revitalise local economies, and promote environmental sustainability.

Conceptually, the 15-minute city challenges the dominant paradigm of a centralised, car-dependent urban development. It argues for functional diversity and spatial decentralisation as key ingredients in building more liveable, resilient, and socially just cities. It calls for the creation of polycentric neighbourhoods, where mixed-use planning enables residents to meet most of their needs locally [

11].

Methodologically, the model requires a shift in planning frameworks and tools. It draws on principles from tactical urbanism, circular economy, and social innovation, and advocates for participatory governance involving local authorities, citizens, and other urban stakeholders. Rather than a prescriptive solution, the 15-minute city should be understood as a flexible and context-sensitive framework adaptable to different scales and urban realities [

11].

This article addresses the growing interest in proximity-based urban planning by critically examining its applicability within the Portuguese context. Portugal is a country with strong asymmetries in population density, mobility infrastructures, and access to public services, especially between coastal and interior regions. The northern region, in particular, offers a relevant case study: it comprises highly urbanised areas, such as the Porto Metropolitan Area, intermediate territories like Cávado or Ave, and low-density, ageing regions, such as Terras de Trás-os-Montes. This diversity provides a unique opportunity to analyse the operationalisation of the 15-minute city model across distinct urban and territorial contexts. This study explores the extent to which planning instruments, particularly Sustainable Urban Mobility Action Plans (SUMAPs), integrate proximity-based principles in practice and how spatial accessibility varies across these territories. Based on these considerations, this study pursues three specific objectives:

- (1)

To analyse the evolution and scope of the scientific literature on proximity-based urbanism in Portugal, particularly in relation to the 15-minute city model;

- (2)

To examine the degree of integration of the model’s core principles—proximity, diversity, density, digital connectivity, and active mobility—into Sustainable Urban Mobility Action Plans (SUMAPs) from the eight intermunicipal communities (CIMs) of northern Portugal;

- (3)

To assess territorial disparities in access to essential services, namely, healthcare and education, through pedestrian-based isochrone analysis, identifying areas that align with or diverge from the normative proximity thresholds of the 15-minute city.

Based on these objectives, two research questions were defined to structure the research process:

RQ1: How is the “15-minute city” concept being interpreted and integrated into Portuguese academic debate and planning instruments?

RQ2: How do spatial disparities in accessibility to essential services shape the practical feasibility of the “15-minute city” model in Northern Portugal?

This article contributes to the international debate on proximity-based urbanism by offering a critical analysis of how the “15-minute city” model is being indirectly translated into policy and planning practices in a Southern European context. By combining bibliometric, policy, and spatial analyses, this study seeks to understand the extent to which planning instruments in northern Portugal incorporate the model’s core principles and to assess the territorial feasibility of proximity-based access to services. This approach contributes not only empirically to the literature but also raises conceptual reflections on how global urban models are appropriated and adapted under diverse governance and spatial regimes.

2. Theoretical Framework: The 15-Minute City Model

2.1. The State of the Art

The growing unsustainability of contemporary European urban organisations is marked by congestion, socio-spatial segregation, pollution, and long commuting times. In addition, the COVID-19 crisis has intensified critical urban issues, bringing to the fore weaknesses such as economic instability, the climate crisis, social inequalities, the lack of services at the local level, and incoherent land use [

13,

14,

15]. In the face of these challenges, new approaches to sustainable urban transition are emerging, focusing on proximity and the functional reorganisation of the territory.

One of these proposals is the concept of the 15-minute city, in which Moreno advocates the restructuring of urban space to ensure that all citizens can access essential services, such as employment, education, health, or leisure, within 15 min on foot or by bicycle [

11,

16]. In particular, the basis of this model is the creation of multifunctional neighbourhoods, which prioritise the coexistence of multiple functions and optimise the time spent in communities in a given place [

11,

14]. The “15-minute city” model, popularised by Carlos Moreno, builds upon a wider lineage of urban theories, including compact city theory, sustainable urbanism, and neighbourhood unit planning. The model synthesises longstanding concerns with walkability, land-use mix, and local accessibility that date back to Jane Jacobs’ critiques of mono-functional zoning and to sustainable city agendas of the late 20th century. Its guiding principles—proximity, density, diversity, and ubiquity—seek to reconfigure urban life around everyday accessibility rather than commuting efficiency, aligning with chrono-urbanism (the synchronisation of urban time and space) and the “complete neighbourhood” concept developed in planning literature.

This approach reduces the need for long and frequent commutes and reliance on private vehicles [

11], which potentially contributes to a significant reduction in carbon footprint and mitigation of climate change. At the same time, it promotes the active involvement of people in decisions about the territory and favours a higher quality of urban life [

16]. In this context, the notion of chrono-urbanism emerges as a complement to the idea of proximity by proposing the integration of time as an essential dimension of urban planning. According to Eleutério et al. [

17], the synchrony between the uses of territory and the time of urban life is fundamental to ensure the well-being of the population, in line with what Moreno et al. [

11] discussed, and the quality of urban life is inversely associated with the amount of time invested in transport. It is preferable that the pace of the city is defined by people, not by individual vehicles [

16].

In addition to the temporal dimension, the model proposes a profound transformation of the city based on diversity and mixed land use, promoting the coexistence between different activities, cultures, and social profiles [

11,

17]. In this sense, the concept is intrinsically linked to accessibility, and it must be understood holistically, considering infrastructures, spatial organisation, transport times and costs, and urban design [

16]. However, the strategy is not to build, but focuses on adapting existing spaces for multiple uses, with placemaking at the core of urban action.

In general, the 15-minute city is based on four structuring principles: proximity, density, diversity, and ubiquity. As described by Pozoukidou & Angelidou [

14], proximity ensures direct access to essential infrastructures and services; density is related to the population concentration that enables the efficient functioning of equipment and services; diversity requires the existence of mixed land uses and social inclusion; and ubiquity values digitalisation and connectivity as enablers of universal access.

Within this logic, the neighbourhood assumes itself as the fundamental spatial unit of urban life. As Pozoukidou & Chatziyiannaki [

13] point out, this is not just an administrative entity but should be understood as a space for community living and local identity. The objective is to optimally allocate resources on an urban scale, bringing services closer to the population and promoting networks of autonomous, interconnected, and sustainable neighbourhoods [

13,

17].

Regarding the positive impacts, on the one hand, social cohesion and socio-spatial justice are strengthened through the control of dispersed urbanisation, which fosters neighbourhood relations and the construction of a sense of place and community [

11]. In terms of public health, the incentive to active mobility offers positive effects on the reduction of a sedentary lifestyle. From an economic perspective, the walkable city structure values local services, thereby supporting local commerce. It can also boost tourism by creating attractive cycling routes and public spaces that are linked to local heritage.

One of the emblematic examples of the practical application of this concept can be found in the city of Paris. Since 2020, the French capital has adopted urban policies aimed at reducing car dependence, expanding the cycling network and requalifying public spaces [

17].

However, several authors have pointed to the limitations and challenges of this proposal. Montgomery [

18], for example, warns that not all urban functions can be located within walking distance, such as hospitals, universities, or large logistics centres, which require articulation between the logic of proximity and polycentric structures. Pozoukidou & Chatziyiannaki [

13] also reinforce the importance of integrating multiple scales of planning, with a focus on territorial equity. The successful application of the model, therefore, depends on contextual factors, such as urban and social morphology, local legislation, and governance systems, which vary from city to city. More specifically, geographical proximity, understood as the co-location of people, services, and activities, is fundamental for equity in access to urban opportunities [

13].

In addition, resistance to change, the need for adapted infrastructure, and the high costs of urban reorganisation are significant barriers. Additionally, there is a risk of gentrification, real estate speculation, and social exclusion, if there are no effective regulation mechanisms and inclusive policies [

11,

15]. Thus, the implementation of this urban model requires a participatory approach that is sensitive to pre-existing inequalities, incorporating the principles of spatial justice and the right to the city.

Despite its popularity, the model has also been subject to critique. Scholars have questioned its applicability in dispersed territories, the lack of regulatory clarity, and the risk of reproducing socio-economic inequalities under a progressive urbanist discourse. In particular, critiques have drawn attention to its potential for gentrification and exclusion in contexts lacking strong planning safeguards. As such, the 15-minute city should be approached not as a universally applicable template but as a context-sensitive heuristic whose implementation must be critically assessed against its normative aspirations.

In summary, the 15-minute city presents itself as an innovative and multifaceted model, capable of responding to the contemporary challenges of cities, as long as it is adapted to local specificities and supported by integrated public policies. By refocusing planning on the local scale, proximity, and citizen participation, this concept proposes a fairer, more sustainable, and humane urban future, mitigating the dispersion and disconnection promoted by decades of zonal planning.

2.2. 15-Minute City Scientific Research: A Growing Topic Worldwide, but Still Rare in Portugal

Academic interest in the concept of the “15-minute city” and its intersections with urban planning has grown significantly in recent years, as demonstrated by the dataset of 205 publications indexed in the Web of Science. These publications reflect the evolving nature of urban research with a focus on accessibility, proximity, and sustainable urban forms. The trajectory of this body of literature reveals clear shifts in temporal distribution, thematic focus, methodological diversity, and geographical scope.

The academic literature on the “15-minute city” has evolved along three main thematic axes: (i) theoretical elaboration and conceptual framing, often grounded in compact city theory, chrono-urbanism, and sustainable urbanism; (ii) empirical measurement of accessibility and service distribution through GIS-based and quantitative methods; and (iii) critical assessments of governance, implementation barriers, and socio-spatial equity implications. Most recent studies focus on large metropolitan contexts, particularly in France, China, and North America, with limited engagement from Southern Europe.

Initially, the concept of the “15-minute city” was not explicitly referenced in the scholarly literature. Early publications prior to 2020 touched upon adjacent themes, such as urban sustainability, walkability, and accessibility planning, but without naming the model per se [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. For instance, a 1993 article in

Landscape and Urban Planning explored the impact of changes in rural-to-urban migration patterns on landscape perception—an issue indirectly tied to urban transformation and resident accessibility [

25]. These sporadic references continued throughout the 2000s and 2010s, yet it was not until the early 2020s that the term gained significant traction in academic debates.

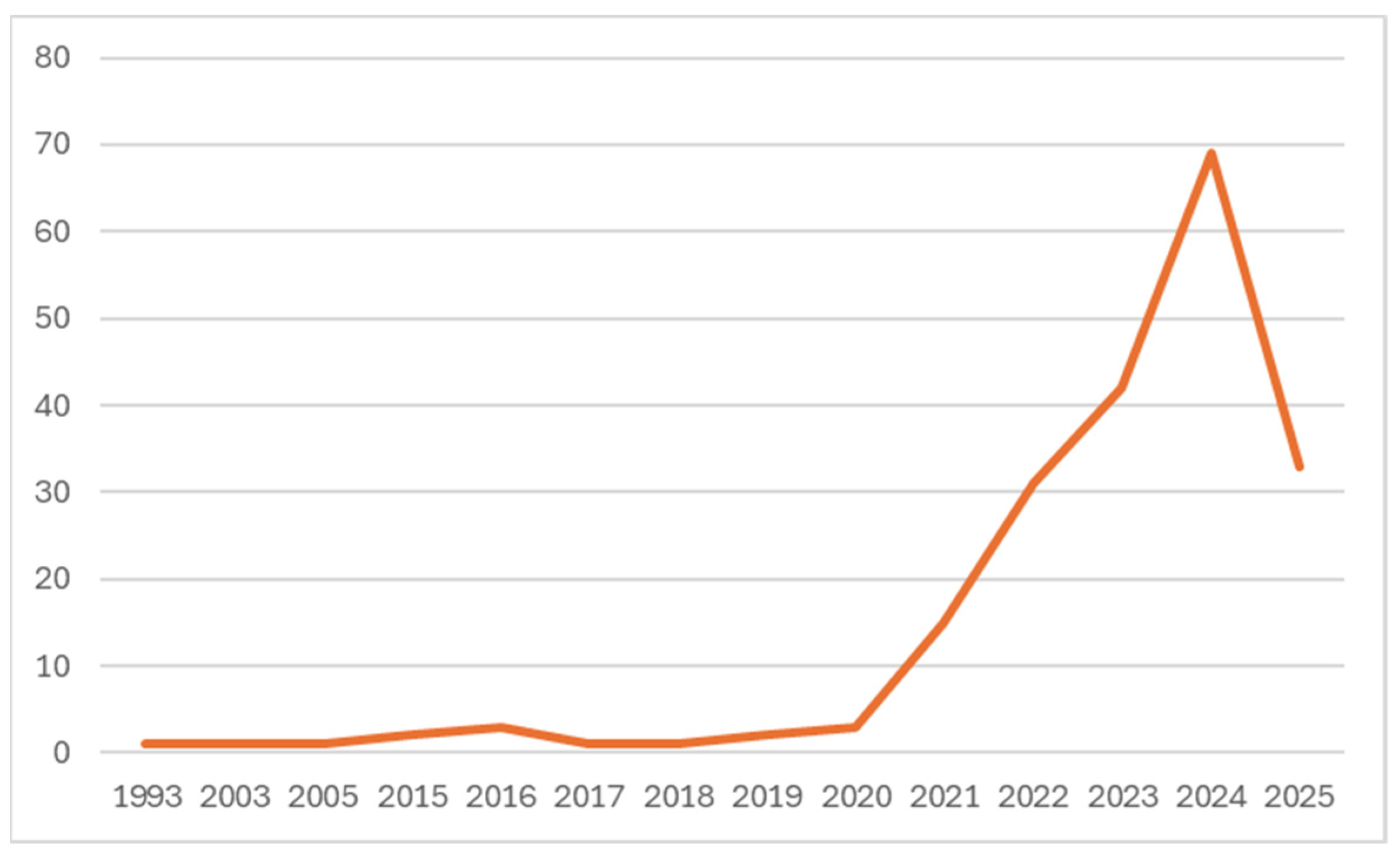

The turning point occurred in 2021, when the number of publications increased sharply. This trend continues with a remarkable rise from 15 publications in 2021 to 31 in 2022, followed by 42 in 2023, and peaking at 69 in 2024. Even the preliminary data for 2025 already lists 33 records (

Figure 1).

This growth coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought renewed attention to the importance of proximity-based urban living [

13,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Restrictions on mobility prompted rethinking of urban systems, placing local access to essential services, green spaces, and employment opportunities at the heart of urban policy and planning discourses.

Thematic developments within the literature have also evolved in line with these socio-political shifts. Initially, research focused on sustainable mobility and non-motorised transport. A typical example is the 2022 study titled “Is the 15-minute city within reach? Evaluating walking and cycling accessibility to grocery stores in Vancouver” [

30], which applied GIS-based models to evaluate cycling networks and their role in facilitating local urban living. These studies [

15,

31,

32,

33,

34] laid the groundwork for subsequent efforts to operationalise the 15-minute framework in planning strategies.

As the literature matured, the thematic scope broadened. Recent studies increasingly focus on the spatial distribution of urban services [

14,

35,

36], urban form adaptation [

37,

38,

39,

40], and mixed-use planning [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. For example, “Planning urban proximities: An empirical analysis of how residential preferences conflict with the urban morphologies and residential practices” [

46] critically examines the adoption of urban proximity planning, questioning its actual ability to promote socially inclusive cities. The results show that preferences are relatively stable but are adaptable to changing circumstances, with spatial variations and a mismatch between aspirations and actual practices. The article “Rethinking urban utopianism: The fallacy of social mix in the 15-minute city” [

47] investigated how spatial proximity does not automatically translate into equitable access, highlighting the risk of reinforcing existing socio-economic divides through ostensibly progressive planning models.

In terms of methodology, early approaches were predominantly conceptual [

48] or policy-oriented [

20,

49]. Over time, however, there has been a marked increase in empirical research using spatial analysis, big data, and simulation models [

50,

51,

52]. The geographical focus of research has also diversified. While early studies were often abstract or based on European capitals, such as Paris, London, and Barcelona [

53,

54], later work has expanded to medium-sized cities [

44,

55] and non-Western contexts [

56,

57]. Paris remains a flagship case, especially following mayor Anne Hidalgo’s promotion of the concept as a core urban strategy.

In sum, the 15-minute city has emerged from an aspirational planning ideal to a multi-dimensional, empirically investigated framework. Its interdisciplinary appeal spans urban design, geography, transport planning, social policy and environmental studies. The literature shows a growing commitment not only to refining the concept but also to testing its real-world viability and interrogating its implications for equity and resilience in contemporary cities.

In Portugal, academic engagement with the model remains limited and fragmented. The small number of scientific publications, mostly post-2021, reflects a delayed adoption that can be explained by several factors: the absence of national strategic references to the model, low institutional capacity in small municipalities, and the persistence of a transport-centric planning culture. These characteristics are emblematic of broader challenges in Southern European urban governance, where institutional inertia and fiscal constraints frequently delay the uptake of international urban agendas. Early works emphasize theoretical and critical reviews of urban compactivity and sustainability models, exploring the political, social, and environmental dimensions of compact city planning [

58]. Others investigate spatial planning strategies that integrate chrono-urbanism and the emergence of new working spaces through comparative case studies, such as Oslo and Lisbon [

59], or apply GIS-based methods to assess the benefits of compactification in Portuguese cities like Coimbra [

51]. These approaches highlight accessibility, equity, and active mobility as core concerns in adapting the 15-minute city principles to the Portuguese context.

More recent contributions reflect an evolution towards nuanced and critical engagements with the concept. These include a call to extend the 15-minute model to nocturnal urban life and social inclusion during nighttime hours [

60], a global review and typology of implementation practices [

61], and a localised case study in Lisbon parishes to test the model’s practical application through measurable indicators [

62]. Together, these studies reveal a trajectory from conceptual framing and broad theoretical reflection to empirical testing and critical refinement of the 15-minute city model, with increasing attention to spatial justice, equity, and governance challenges.

Having mapped the academic evolution of the 15-minute city model, we now examine its explicit incorporation in intermunicipal mobility plans before assessing spatial accessibility across northern Portugal (

Section 4).

3. Methods

The present study employed a multi-step approach to investigate the integration of proximity-based principles in Portuguese urban mobility planning. First, a comprehensive literature review was conducted through systematic analysis of scientific articles and key policy documents. We screened peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings, and official reports, identifying seminal works on urban mobility, compact-city theory, and sustainable planning. Emphasis was placed on extracting conceptual frameworks and empirical findings relevant to the “15-minute city” paradigm, as well as on mapping the evolution of these ideas over time.

Second, a targeted bibliometric review was carried out to map the evolution of scientific literature on the “15-minute city” in both international and Portuguese contexts. The primary database used was Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate), selected due to its curated indexing and suitability for bibliometric analysis. The search strategy combined the terms “15-minute city” with variations of “urban”, “planning”, and “Portugal”, limited to the years 2000–2025 and to articles in English, Portuguese, or Spanish. Boolean operators and truncation (e.g., “urban*”) were applied to capture broader thematic links. Additional searches were conducted in Scopus and Google Scholar to identify relevant national literature and policy documents. The inclusion criteria comprised peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and institutional reports addressing proximity-based planning, urban accessibility, or 15-minute city frameworks. The exclusion criteria included purely technological or engineering studies without spatial planning relevance. A total of 205 articles were retrieved from Web of Science, from which duplicates and non-relevant entries were removed after abstract screening, resulting in a final corpus of 162 publications. Although a formal PRISMA protocol was not followed, we structured the selection process through systematic filtering and ensured thematic consistency throughout the sample.

Third, we performed a structured content analysis of all Sustainable Urban Mobility Action Plans (SUMAPs, or PAMUS in Portuguese) from the eight intermunicipal communities of northern Portugal. The eight SUMAPs analysed were selected because they constitute the first comprehensive and methodologically comparable generation of intermunicipal mobility plans in Portugal, developed in 2016 under the EU Sustainable Mobility framework. Although several municipalities and CIMs are currently revising or updating these plans, at the time of writing, most updated versions were either not public or not standardised, thus compromising comparability. These 2016 plans therefore offer a coherent baseline to assess whether and how proximity-based concepts were incorporated in the initial wave of strategic mobility planning. Each plan was examined according to a six-dimension reading key. The six analytical dimensions selected for the evaluation of SUMAPs were directly derived from the foundational principles of the 15-minute city model, particularly as conceptualised by Moreno et al. [

11] and subsequent operational adaptations [

14,

16,

17]. These principles—proximity, density, diversity, ubiquity, and walkability—serve as the backbone for urban environments where residents can access key daily needs within a short walking distance. Our analytical dimensions thus correspond as follows:

- -

Spatial proximity captures the territorial articulation of functions and the presence (or absence) of polycentric structures.

- -

Access to essential services evaluates the degree to which daily functions (e.g., health, education, employment) are addressed in planning.

- -

Density relates to the critical mass required to sustain services and infrastructure.

- -

Diversity and multifunctionality reflect the functional mix within neighbourhoods.

- -

Ubiquity and digitalisation assess the availability of real-time information systems and smart mobility platforms.

- -

Investment in active mobility corresponds to the model’s emphasis on walkability and low-carbon transport modes.

These dimensions enable a structured and comparative assessment of how SUMAPs translate the core tenets of the 15-minute city into planning language and policy instruments. For each dimension, text passages were coded and synthesised to identify explicit objectives, proposed measures, and implementation mechanisms. This thematic coding enabled systematic comparison across territories and the identification of shared priorities and gaps.

To assess territorial accessibility in alignment with the principles of the 15-minute city, this study focused on healthcare (primary health centres and hospitals) and education (primary and secondary schools) services. These services were selected due to their essential role in daily life and their centrality in the proximity-based urban model. Importantly, they are also spatially stable and georeferenced in official datasets, allowing for objective isochrone modelling. Other functions, such as employment, recreation, or commerce, although relevant to the 15-minute city concept, lack fixed spatial anchors or sufficient data resolution to be analysed consistently across territories. Employment locations in particular are highly dispersed, subject to temporal variability, and often unknown at the individual level, making them unsuitable for isochronal analysis with the same methodological robustness. The 15-minute pedestrian threshold was chosen, as it corresponds to the core normative parameter of the model proposed by Moreno et al. [

11], which defines ideal proximity as access to essential services within 15 min on foot or by bicycle. The isochrones thus operationalise this definition, allowing a spatially grounded assessment of proximity and accessibility in different territorial contexts. An empirical spatial analysis of service accessibility was undertaken. Using ArcGIS Pro 3.0.0’s Network Analyst extension, pedestrian isochrones were calculated for cutoffs of 5, 10, and 15 minutes’ walking time, based on the ArcGIS

® StreetMap™ Premium Europe 2025 network dataset. We mapped isochrones centred on healthcare facilities (primary health centres and hospitals) and educational institutions (primary and secondary schools) to quantify the proportion of each Intermunicipal Community (CIM) population within each travel-time threshold. These spatial metrics provided an objective measure of proximity to key services, complementing the qualitative insights from the SUMAPs review and allowing for a robust assessment of metropolitan–rural disparities in service accessibility.

4. Results

4.1. 15-Minute City: Integration on Regional Planning?

In the 15-minute-city context, Sustainable Urban Mobility Action Plans (SUMAPs), such as those adopted in Portugal, represent a strategic tool for operationalising this conceptual paradigm because, unlike traditional planning focused on car fluidity, SUMAPs prioritise population well-being, equity in access to mobility, and the improvement of urban environmental quality, which are assumed as ambitions of this type of city.

Thus, in recent years, the Portuguese CIMs have sought to modernise regional mobility frameworks by integrating principles of proximity, equity, and sustainability. Through the six analytical dimensions, we can discern both shared ambitions and local specificities across the eight CIMs: Alto Minho, Alto Tâmega, Área Metropolitana do Porto (AMP), Ave, Cávado, Douro, Terras de Trás-os-Montes, and Tâmega e Sousa (

Table 1).

Across the board, explicit invocation of the 15-minute city remains rare. Most CIMs articulate goals of reducing trip lengths and strengthening local networks without adopting the terminology itself. Alto Minho and AMP alike emphasise improved local accessibility through closer clustering of transport nodes, yet neither directly references the proven urbanist model of 15-minute proximity. Cávado and Terras de Trás-os-Montes similarly acknowledge modal integration and distance barriers but stop short of embedding proximity-based land use. Tâmega e Sousa is the sole outlier, with effectively no treatment of spatial proximity logic, signalling a persistent reliance on traditional catchment and intermunicipal flows rather than hyper-local neighbourhood planning. Alto Tâmega’s plan hints at cluster-based service provision around council seats, indicating nascent sensitivity to spatial proximity although without explicit framing.

All CIMs record substantial attention to ensuring multimodal connectivity to schools, healthcare, and employment hubs. AMP’s integrated fare system and coordinated Andante ticketing exemplify a mature metropolitan approach. Ave quantifies success in that 82 percent of residents access urgent care within fifteen minutes, setting a benchmark for service accessibility. Alto Tâmega and Cávado integrate school transport schemes and centralised scheduling of health appointments to overcome rural service deserts. Terras de Trás-os-Montes, with its low and ageing population, employs transport-on-demand systems to reach isolated settlements. Tâmega e Sousa remains comparatively underdeveloped, offering only broad mobility goals without service-specific stratagems. The Douro leverages its integrated Territorial Investment Initiative (ITI) to underwrite new healthcare and educational facilities, thereby improving baseline access.

Detailed demographic analysis underpins most mobility strategies. AMP’s granular density maps and pendular-movement studies inform high-frequency corridors and demand-responsive services. Cávado and Ave employ similar mapping to distinguish core urban nodes (e.g., Braga, Guimarães) from peripheries, ensuring investments track population clusters. In Alto Minho and Alto Tâmega, relatively sparse densities—33 hab/km2 overall in Alto Tâmega, with peaks of 69.8 hab/km2 in Chaves—necessitate flexible or demand-responsive transport solutions rather than fixed-route networks. Terras de Trás-os-Montes constitutes the most extreme case of demographic dispersion, where transport planning must reconcile widely scattered settlements with economies of scale. The Douro’s polycentric reinforcement under its PDCT and PEDU schemes seeks to consolidate urban–rural linkages through targeted densification of defined nodes. Tâmega e Sousa again lags in translating density data into concrete spatial planning.

Most CIMs incorporate social equity and inclusion as guiding principles, yet true multifunctional land-use planning remains limited. AMP and Ave support inclusive mobility policies and urban regeneration projects that promote mixed uses, albeit without robust zoning instruments. Cávado and Alto Minho highlight social cohesion through flexible transport modes, yet multifunctional urban cores receive only cursory treatment. In the more rural CIMs, inclusion efforts focus on service reach, such as transport-on-demand for isolated seniors in Terras de Trás-os-Montes and school-transport subsidies in Alto Tâmega but stop short of fostering mixed-use hubs that might combine residential, commercial, and civic functions. The Douro’s emphasis on territorial asset valorisation gestures toward multifunctionality but does not yet underpin explicit land-use reforms. Tâmega e Sousa offers the weakest articulation of diversity, relying on broad terms of social inclusion without clear multifunctional strategies.

Digital platforms and intelligent transport systems (ITS) feature prominently in AMP, Cávado, Alto Minho, Ave, and Douro. These CIMs deploy mobile applications (e.g., MOVE-ME), real-time passenger information, and integrated back-office observatories to optimise operations and user experience. Alto Tâmega’s Innovation Pole for Smart Transport Systems indicates an advanced commitment to vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure communication. Terras de Trás-os-Montes and Tâmega e Sousa display only rudimentary digital solutions, such as basic transport-information websites, reflecting both lower ridership volumes and budgetary constraints. Nevertheless, even in these contexts, initial forays into digitalisation provide a foundation for future expansion of ITS functionalities.

Active mobility emerges as a unifying investment priority. AMP’s extensive pedestrian corridors and urban ecovias are matched by cycle-parking expansions at Park & Ride facilities. Cávado and Ave propose large-scale bike sharing and “quiet zones” to encourage walking, while Alto Minho and Alto Tâmega allocate substantial PAMUs funds (c. EUR 23 million in Alto Tâmega) to intermunicipal cycling and pedestrian networks. Even in predominantly rural Terras de Trás-os-Montes, modest infrastructure upgrades (e.g., new sidewalks and rural cycle paths) are a signal of a shift toward accommodating non-motorised travel. In contrast, Tâmega e Sousa’s active-mobility measures remain under-specified, lacking concrete targets or dedicated budgets.

The comparative analysis reveals a clear metropolitan–rural gradient. Metropolitan CIMs, such as AMP and Ave, exhibit mature, digitally integrated mobility frameworks with explicit service-level targets and diverse active-mobility investments. Mid-density territories, like Cávado and Alto Minho, combine flexible service models with burgeoning ITS deployments. Rural CIMs, including Terras de Trás-os-Montes and Alto Tâmega, prioritise demand-responsive solutions and foundational active-mobility infrastructure, while Tâmega e Sousa lags behind in almost every dimension. Despite varying degrees of emphasis, all eight CIMs demonstrate a shared commitment to enhancing accessibility, promoting sustainability, and reinforcing intermunicipal cooperation.

4.2. Territorial Diversity and the Challenges of Implementing the 15-Minute City Model in Northern Portugal

The implementation of the 15-minute city model across different territorial contexts in northern Portugal is marked by significant heterogeneity. While the model advocates for spatial justice and quality of life through the proximity of essential services, its real-world application reveals notable asymmetries across the eight NUTS III regions of the north.

The data reveal that while educational services, particularly at lower levels, tend to be more accessible throughout the region, access to healthcare is a critical weakness. At the regional level, only 39.23% of the population in the north has a primary healthcare unit or family health unit within a 15-minute walk, in contrast to 76.7% with access to pre-school and 74.12% to basic education.

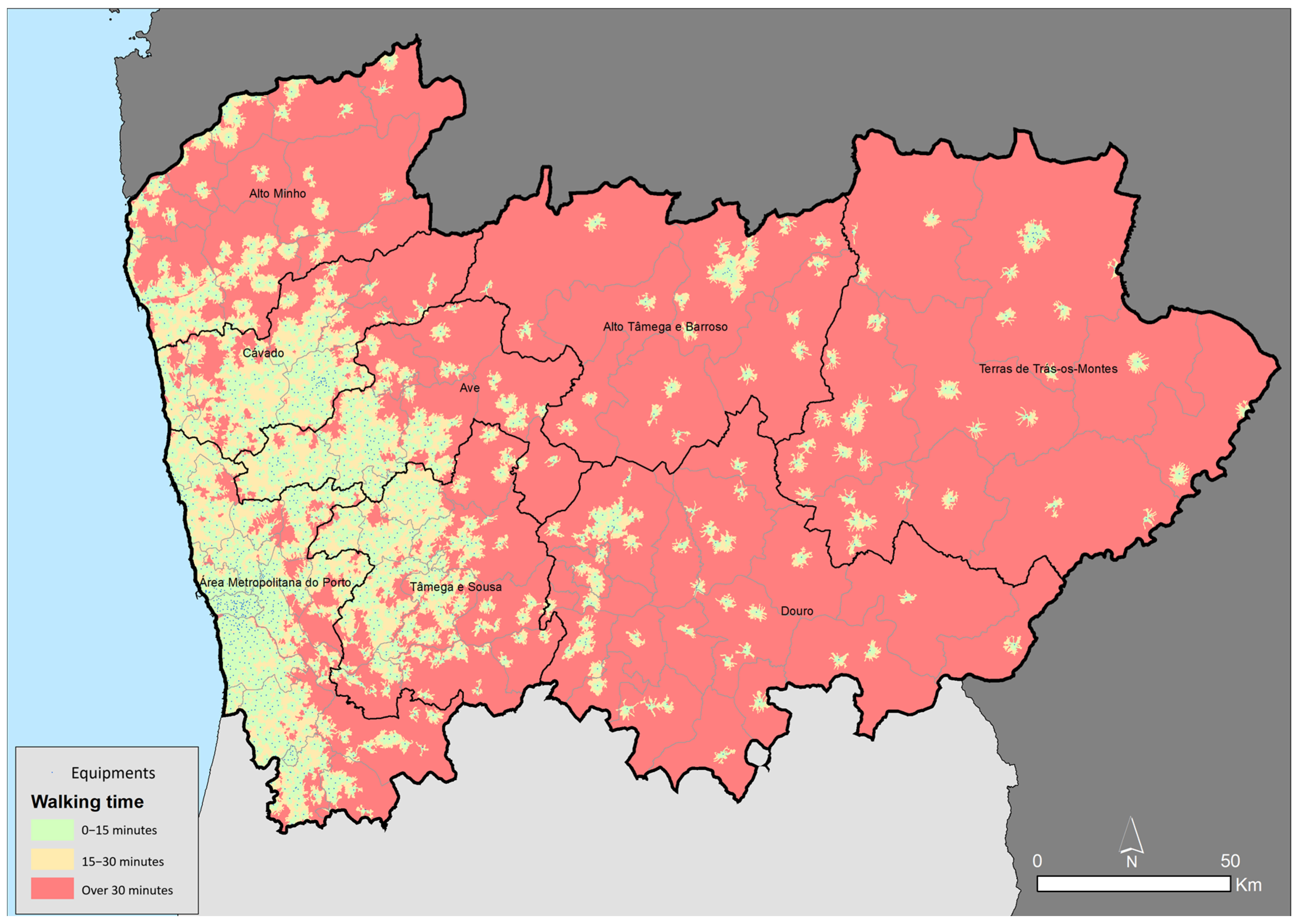

There is some evidence of proximity-based access to key services, particularly in education. However, this proximity is largely the result of uncoordinated or unplanned dynamics, especially in early childhood education. The relatively high levels of access to pre-school establishments (

Figure 2) are, in many cases, underpinned by private sector initiatives, notably, the “Creche Feliz” programme. This has played a decisive role in bridging accessibility gaps, particularly where public provision remains insufficient.

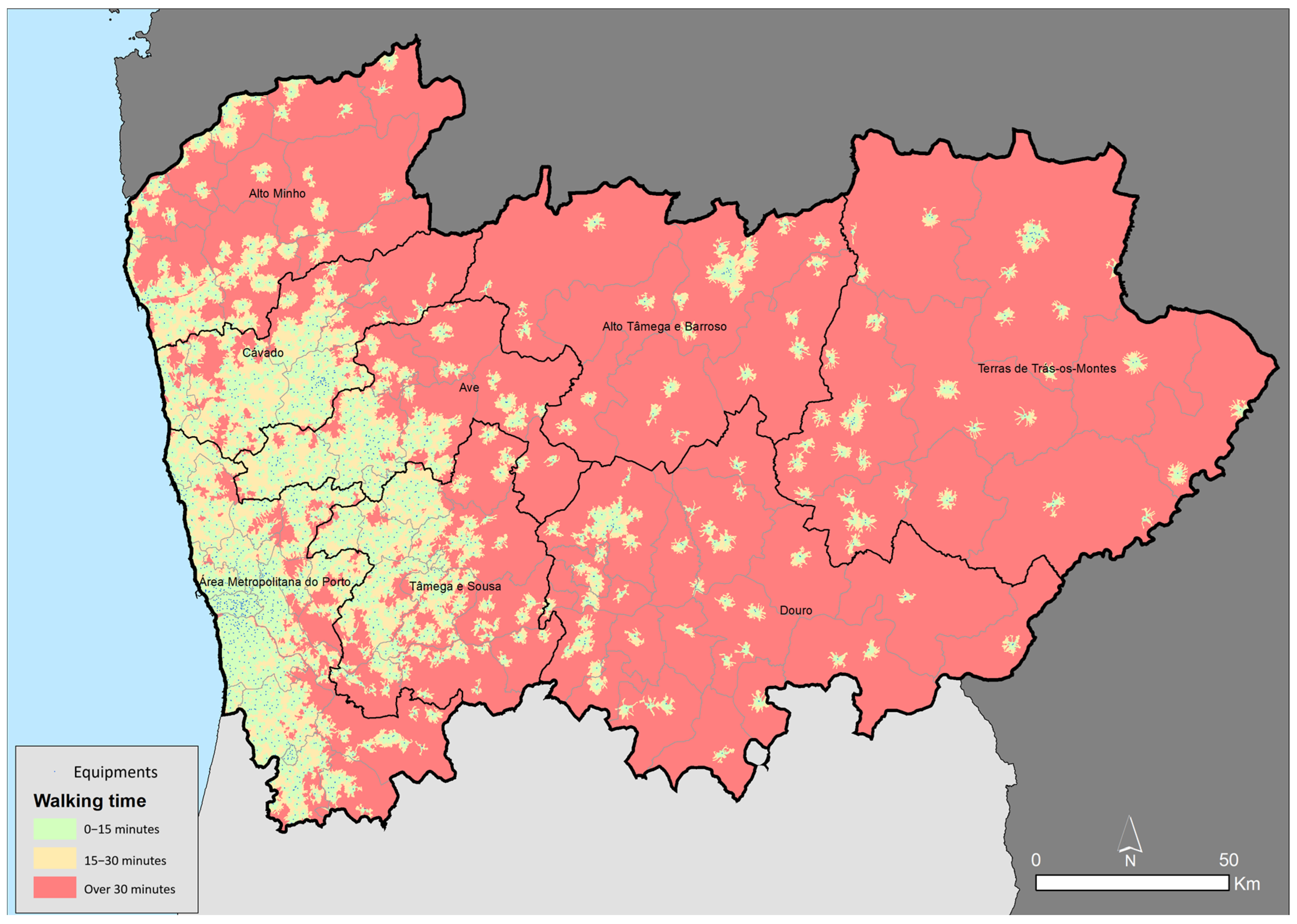

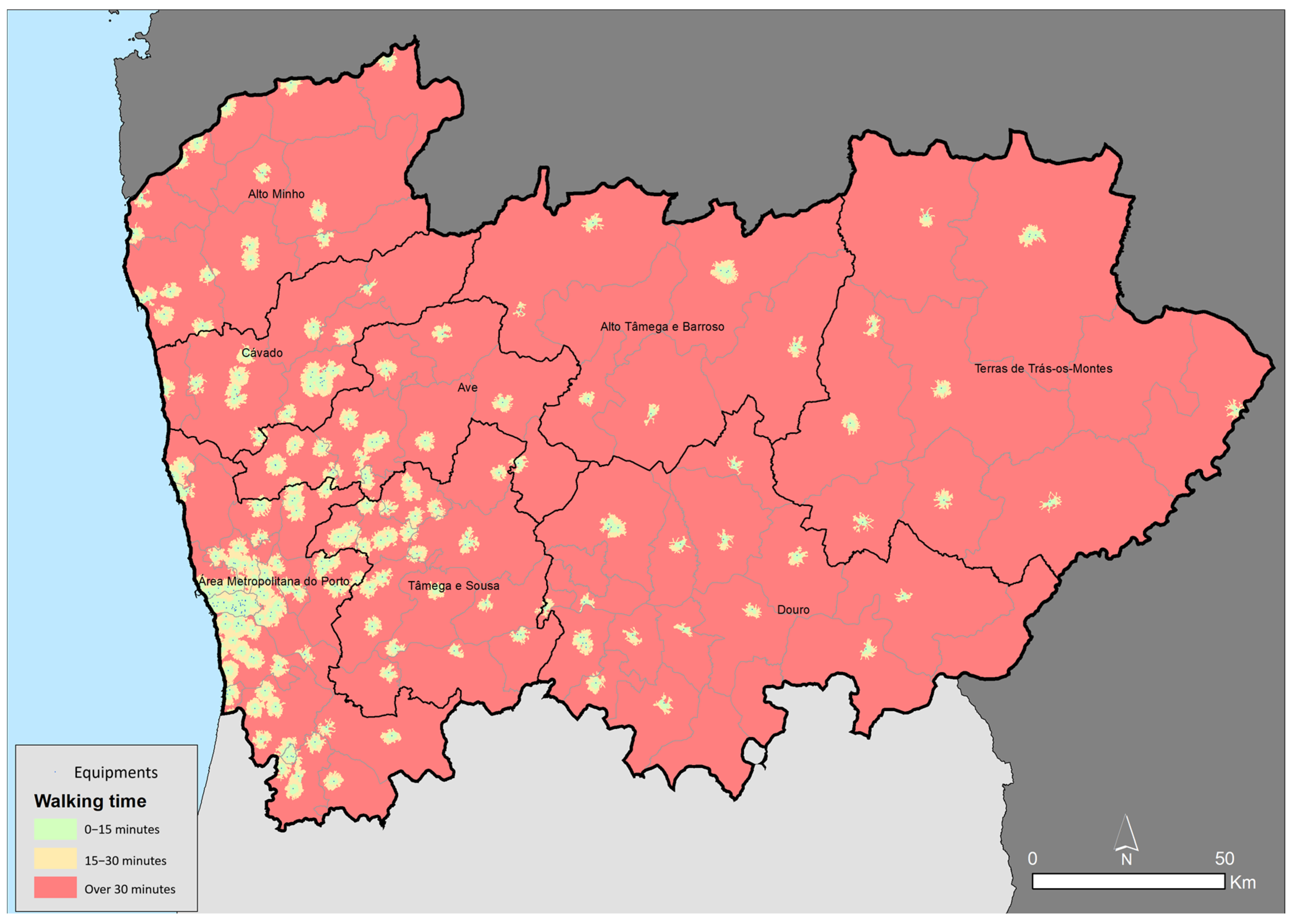

Despite this, sharp territorial disparities persist. The Metropolitan Area of Porto (AMP) stands out across all indicators, with over 86% of the population having access to pre-school (89.31%), and primary (86.19%) (

Figure 3) and basic schools (88.42%) (

Figure 4) within a 15-minute walking distance. AMP also registers the highest proximity to upper secondary schools (42.51%) (

Figure 5) and primary healthcare units (50.67%) (

Figure 6). The Cávado and Ave regions also perform relatively well in educational services, although with noticeably lower levels of accessibility to healthcare (35.51% and 28.68%, respectively). Conversely, rural and peripheral regions, such as Alto Tâmega and Douro, reveal clear disadvantages. In Alto Tâmega, for example, only 36.44% of the population lives within 15 min of a primary school, and merely 19.47% have such access to upper secondary education. Similarly, access to healthcare units is considerably lower across most non-metropolitan areas, with figures ranging from 22.5% in Tâmega e Sousa to 30.11% in Douro. Even in regions like Ave, where educational access is relatively high, the accessibility to health services remains limited (28.68%).

These findings underscore the influence of territorial typologies in shaping the feasibility and operationalisation of the 15-minute city model. Urban areas, characterised by greater density and infrastructural concentration, are naturally more aligned with the model’s principles. In contrast, peri-urban and rural territories face structural limitations that hinder the establishment of essential services within a short walking radius.

While pedestrian accessibility is a core dimension of the 15-minute city model, it is essential to acknowledge the role of motorised transport in ensuring access to services in territories where density and proximity are structurally constrained. The data on road-based accessibility to upper-level education and healthcare services in Northern Portugal reveal further nuances regarding the territorial disparities already identified.

At the regional level, northern Portugal shows higher coverage in road-based access than pedestrian access. For instance, 74.46% of the population has access to hospital units within 15 min by car, compared to only 39.23% to primary healthcare units on foot. Nonetheless, the accessibility advantage provided by road transport does not compensate for the deeper structural asymmetries in service distribution and does not align with the sustainability goals embedded in the 15-minute city model.

In terms of education, access within a 15-minute drive to professional (

Figure 7) and artistic education (

Figure 8) establishments is generally high in the more urbanised regions. The Cávado, AMP, and Ave regions stand out, with over 90% of the population having access to professional education (95.15%, 89.76%, and 92.79%, respectively) and similarly high figures for artistic education (92.7%, 95.38%, and 81.52%). This concentration reflects the centralisation of specialised education infrastructures in urban centres, reinforcing the metropolitan advantage. By contrast, rural and less populated regions, such as Alto Tâmega and Terras de Trás-os-Montes, register significantly lower accessibility. In Alto Tâmega, only 37.24% of the population lives within a 15-minute drive of a professional school, and 47.76% have access to artistic education facilities. Terras de Trás-os-Montes performs even worse regarding artistic education (27.12%). These figures suggest structural deficits in the distribution of specialised educational offerings, which often require commuting beyond local limits, thereby undermining the principles of territorial equity.

In the domain of healthcare, access to emergency medical services (

Figure 9) and hospital care (

Figure 10) also reflects marked territorial asymmetries. The AMP region again leads in terms of access, with 85.92% of the population within a 15-minute drive of an emergency service and 91.46% within reach of hospital care. The Cávado and Ave regions also maintain relatively high levels of accessibility (75.07% and 75.39% for emergency care, 75.07% and 79.19% for hospital care, respectively). However, Tâmega e Sousa, despite its proximity to urban centres, records alarmingly low figures—only 34.26% of the population can reach an emergency service and 32.53% can reach a hospital in 15 min by car. These values highlight the uneven distribution of healthcare infrastructure even in semi-urban regions. Alto Tâmega and Douro also presented moderate-to-low access, with less than half of the population within proximity to hospital units (47.12% and 52.35%, respectively).

5. Discussion

This study offers a comprehensive assessment of how proximity-based principles have permeated Portuguese intermunicipal mobility planning and highlights striking contrasts between metropolitan and rural contexts. First, while the notion of the 15-minute city has gained international traction among urban scholars and practitioners, explicit reference to this paradigm is largely absent from Portuguese SUMAPs. Instead, CIMs speak in terms of reducing travel distances, enhancing local node connectivity, and strengthening intermunicipal links without adopting the exact “15-minute” label. In metropolitan settings, such as the AMP and Ave, policies centre on optimising modal hubs and consolidating pedestrian and cycling networks within existing urban fabrics. By contrast, mid-density territories tend to embrace flexible transport-on-demand services alongside conventional fixed-route systems to address the patchwork of dense cores and low-density peripheries. In truly rural CIMs (Terras de Trás-os-Montes, Alto Tâmega, and Tâmega e Sousa), planners recognised the logic of proximate service delivery only insofar as it can be achieved through subsidised school transport, community shuttles, or occasional demand-responsive buses; the spatial reality of sprawling settlements makes a uniform “15-minute” model impractical without complementary land-use interventions. The results of the isochrone analysis provide an empirical lens through which to evaluate the extent to which different regions approximate or deviate from the principles of the 15-minute city. By applying a pedestrian-based 15-minute threshold to healthcare and education services, the analysis directly operationalises the model’s proximity criterion. The findings reveal a clear gradient: metropolitan territories like AMP approach the ideal of service proximity, while peripheral or low-density regions fall significantly short, exposing the spatial limitations of applying a universal proximity threshold to territorially diverse contexts. This underscores the need for differentiated and context-sensitive adaptations of the model, particularly in rural settings, where physical co-location of services may be structurally constrained.

Second, across all eight CIMs, there is an unambiguous commitment to improving access to essential services, such as schools, healthcare, employment, and emergency response, through multimodal integration and coordinated fare systems. AMP’s Andante ticketing and MOVE-ME real-time app exemplify a high degree of digital maturity, offering residents seamless transfers between metro, bus, and bike-share. Ave quantifies success by noting that over 80 percent of its population can reach urgent care facilities within fifteen minutes, setting an operational benchmark. In more rural CIMs, however, the lack of nearby facilities means that motorised modes remain essential for bridging gaps; service-on-demand schemes mitigate some isolation but cannot fully substitute for denser, mixed-use neighbourhoods.

The spatial disparities observed in the isochrone analysis and the fragmented integration of proximity principles in SUMAPs reflect deeper structural challenges in Portuguese urban and territorial governance. Intermunicipal coordination remains fragile, regulatory tools for mixed-use neighbourhoods are underdeveloped, and planning practices still privilege mobility infrastructure over spatial–functional integration. These patterns are not merely technical but politically and institutionally conditioned, shaped by unequal capacities, historical infrastructural investment biases, and the persistence of sectorial planning cultures. The rhetorical uptake of inclusivity and sustainability in planning documents often lacks translation into enforceable instruments, revealing a gap between discourse and implementation. The comparative analysis reveals not only whether these dimensions are mentioned but how effectively they are spatialised, regulated, and operationalised. While many CIMs reference access, mobility, or inclusivity, fewer articulate how these goals are supported by zoning instruments, performance indicators or governance mechanisms. In particular, functional diversity is often reduced to generic mentions of inclusion, without robust planning tools to ensure mixed-use urban cores. Similarly, while digital platforms proliferate, they are rarely tied to participatory governance or integrated with land-use strategies. These gaps underscore the need to distinguish between rhetorical alignment with the 15-minute city model and its actual territorial implementation.

Third, the linkage between population concentration and mobility investment is sharply delineated. In AMP, detailed GIS-based density mapping informs the prioritisation of high-frequency corridors and dynamic demand-responsive services in the densest wards (over 5 700 inh/km2 in Porto proper). Cávado and Ave replicate this evidence-based approach by distinguishing primary urban cores from rural peripheries. Essentially, investment is followed by the population. Conversely, Alto Tâmega’s overall density of roughly 33 inh/km2 dictates a hybrid strategy combining subsidised inter-municipal buses with promising cycling paths. Terras de Trás-os-Montes and Tâmega e Sousa illustrated the limits of conventional planning: widely dispersed settlements render fixed routes inefficient and undermine cycling and walking modes unless accompanied by significant infrastructural densification or relocate incentives.

Fourth, although all CIMs profess inclusive and multifunctional ideals, land-use policies to foster mixed-use neighbourhoods remain underdeveloped. Metropolitan CIMs leverage urban regeneration grants to retrofit disused sites for housing and local services, yet explicit zoning for true functional diversity is rare. Rural territories focus instead on social equity through transport subsidies and digital call centres, without parallel efforts to co-locate residential, commercial, and civic uses. The result is a partial translation of inclusionary rhetoric into practice: physical proximity of services improves somewhat, but the co-presence of daily needs, employment, and leisure within walkable distances remains aspirational.

Fifth, digitalisation and active-mobility investments converge as core strategies. ITS platforms proliferate in AMP, Cávado, Ave, Alto Minho, and Alto Tâmega, while Terras de Trás-os-Montes and Tâmega e Sousa deploy basic web portals at best. Across all CIMs, substantial PAMUS funding has been earmarked for cycle-path extensions, pedestrian corridors, and “quiet zones,” signalling a shared conviction that non-motorised modes are essential to any proximity model. Yet, the efficacy of these measures will depend on complementing infrastructure with strategic densification and mixed-use planning so that walking and cycling deliver genuine reductions in motorised travel.

Finally, the data on motorised accessibility complement the pedestrian-based analysis and further illustrate the spatial inequalities across northern Portugal. While car-based travel extends the reach of essential services, particularly higher education and hospital care, this mode of access cannot replace the need for local proximity in the everyday functioning of the 15-minute city. These findings reinforce the argument that any territorial adaptation of the model must consider not only urban form and population density but also the spatial allocation of services and the limitations of transport infrastructure in low-density contexts. Thus, the implementation of the 15-minute city model in northern Portugal must be understood through a differentiated territorial lens. While some areas, particularly AMP and Cávado, display favourable conditions for adopting proximity-based urban policies, other territories require targeted, context-sensitive strategies that address spatial inequalities and service deficits. Without such an approach, the model risks reinforcing existing territorial disparities rather than mitigating them.

In sum, Portuguese CIMs display a clear trajectory toward embedding proximity, sustainability, and equity in regional mobility planning. However, the full realisation of a 15-minute ethos will require a deeper integration of land-use reforms, multifunctional zoning, and participatory governance, especially in low-density contexts, where physical proximity cannot emerge from transport policy alone.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Learnings from Portugal

This study has successfully addressed its three main objectives. First, it has demonstrated that international academic production on the “15-minute city” has grown exponentially since 2021, with an increasingly sophisticated articulation of proximity-based planning in urban research. In contrast, Portuguese academia is only incipiently engaging with the concept, with just six scientific publications up to mid-2025. Nevertheless, a shift is observable from conceptual framing and critical theory towards applied case studies using geospatial methods and accessibility metrics. This reveals both the potential and the still-limited maturity of the topic in national scholarship.

Second, the analysis of Sustainable Urban Mobility Action Plans (SUMAPs) across eight intermunicipal communities (CIMs) in northern Portugal has shown that while most plans adopt dimensions aligned with the 15-minute city model—such as promoting active modes, digital integration, or access to services—they do so without explicitly referencing the model or applying it as a comprehensive planning framework. The integration is thus fragmented and technocratic, lacking regulatory, zoning, or governance mechanisms to ensure true multifunctionality and socio-spatial equity.

Third, the spatial accessibility analysis highlights stark territorial asymmetries. Metropolitan areas, such as AMP, offer high walkability to key services, consistent with the 15-minute principle. Conversely, rural and peri-urban territories display structural limitations that inhibit its feasibility. Accessibility to healthcare remains particularly deficient. While motorised travel extends reach, this undermines the core sustainability rationale of the model and reinforces dependence on car-centric infrastructures.

These findings have several implications for urban planning in Portugal, particularly in terms of policy coherence, governance architecture, and spatial justice. Firstly, they highlight the need to reframe Sustainable Urban Mobility Action Plans (SUMAPs) not as isolated technical exercises but as integrated components of broader spatial planning strategies aligned with sustainable development objectives. The current absence of explicit references to the “15-minute city” model in SUMAPs reflects a conceptual and regulatory fragmentation that weakens the coherence between mobility policies, land use planning, and socio-territorial inclusion. It is crucial that national and local planning instruments, such as Municipal Master Plans (PDMs), Urban Rehabilitation Strategies, and Territorial Cohesion Plans, explicitly adopt and adapt the principles of proximity, density, diversity, and ubiquity. This implies the development of binding zoning mechanisms that promote mixed-use neighbourhoods, incentives for adaptive reuse of underutilised spaces, and minimum thresholds for service distribution based on walkability metrics.

Secondly, these findings suggest that a deeper integration of urban planning with social policy and public health is essential to ensure that proximity-based planning does not result in spatially selective benefits or reinforce existing inequalities. In rural and low-density contexts, the practical implementation of the 15-minute logic requires creative solutions, such as mobile services, multifunctional community hubs, and flexible governance instruments, that acknowledge territorial diversity. Intermunicipal coordination emerges as a strategic axis to overcome scale limitations and optimise resource allocation, particularly in dispersed territories. Furthermore, the growing digitalisation of mobility systems should be complemented by inclusive planning practices that do not exclude digitally marginalised populations, ensuring that technological innovation does not exacerbate spatial exclusion.

Finally, a central implication is the need for a cultural and institutional shift in the planning community itself. Urban and regional planners must move beyond sectorial approaches and develop new competences in participatory methods, spatial data analysis, and interscalar negotiation. Planning schools, professional associations, and public institutions should invest in training programmes focused on proximity-based urbanism, enabling a new generation of planners to design, implement, and evaluate policies grounded in the ethos of the 15-minute city, adapted to the Portuguese territorial context.

Thus, in response to the two research questions, this study shows that Portuguese academic engagement with the “15-minute city” remains incipient and fragmented, contrasting with the rapid and diversified international debate, and that the integration of proximity-based principles into Sustainable Urban Mobility Action Plans is partial and largely implicit. Furthermore, the spatial analysis demonstrates that territorial disparities strongly condition the feasibility of the model: while metropolitan areas such as Porto approach its normative thresholds of accessibility, rural and peri-urban contexts reveal structural limitations, underscoring the need for differentiated, context-sensitive adaptations rather than a uniform application of the “15-minute city” framework.

6.2. Recommendations

Based on the concluding remarks, it is recommended that urban and territorial policies be guided by the incorporation of the 15-minute ethos, in which territorial instruments must explicitly integrate the four pillars of proximity, density, diversity, and ubiquity not as abstracts principles but as criteria that are spatially operationalised at all planning scales. This integration should be supported by targeted financial incentives for urban-regeneration projects and the establishment of intermunicipal observatories that monitor accessibility indicators in real time. Such mechanisms can enhance territorial cohesion, enabling adjustments based on concrete data and promoting collaboration between territories. In addition, participatory governance and regulatory safeguards are crucial to ensure a functional mix, prevent gentrification, and secure equitable service distribution. These measures highlight the importance of governance capacity and spatial justice in translating the 15-minute city model into solid territorial strategies. Although grounded in the Portuguese case, our analytical framework and GIS-based accessibility protocol can be directly applied to other territories to diagnose proximity gaps and inform mixed-use policy instruments. These transferable tools offer a practical blueprint for evaluating and strengthening 15-minute city strategies under diverse governance regimes.

Beyond technical gaps, these findings underscore structural needs for integrated governance, regulatory instruments, and community participation to translate the 15-minute city ethos into equitable territorial strategies.

6.3. Study Limitations

Future research should address several gaps that emerged from this study and contribute to the consolidation of a research agenda on the 15-minute city adapted to the Portuguese context. Firstly, it is essential to incorporate the forthcoming generation of SUMAPs (expected after 2025) into new analyses, assessing whether the lessons learned from the first implementation cycle and the post-pandemic recovery have led to a more explicit and operational integration of proximity-based principles. Comparative evaluations between the first and second generations of SUMAPs could reveal patterns of institutional learning and governance adaptation across different CIMs. Secondly, more qualitative, actor-centred research is needed to understand how local stakeholders, including municipal planners, civil society organisations, and residents, perceive and engage with the concept of proximity. Ethnographic studies, participatory mapping, focus groups, and deliberative processes can generate critical insights into the socio-cultural dimensions of proximity, including issues of trust, safety, time-use patterns, and symbolic geographies of everyday life. These approaches are particularly relevant in contexts where formal planning instruments are weak or slow to change and where informal practices play a significant role in shaping access to services. Thirdly, future studies should explore the integration of temporal dimensions, such as daily and seasonal rhythms of urban life, into spatial accessibility modelling. Chrono-urbanism, while conceptually acknowledged in the literature, remains underexplored in applied research. Dynamic isochrone modelling, coupled with GPS or mobile phone data, can shed light on real-time accessibility variations and inform adaptive service provisioning. Fourthly, longitudinal assessments of pilot interventions inspired by the 15-minute city logic, such as neighbourhood retrofitting, street requalification, school cluster redesign, or mobility hubs, can provide empirical evidence on implementation challenges, behavioural impacts, unintended consequences (e.g., gentrification), and governance bottlenecks. These case studies should ideally be co-produced with local stakeholders, contributing to action-research models that simultaneously advance theory and practice. Moreover, transdisciplinary collaborations between geographers, architects, sociologists, transport engineers, and public health experts are vital to fully grasp the complex interdependencies that proximity-based planning entails.