The Differential Impact of Human Capital on Social Integration Among Rural–Urban and Urban–Urban Migrants in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Integration

2.2. Human Capital and Migrants’ Integration

2.3. Differences in the Impact of Human Capital on Social Integration Between Rural–Urban and Inter-Urban Migrants

3. Data, Measurement, and Method

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Method

3.3.1. Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition

3.3.2. Quantile Regression Model

3.3.3. Quantile Decomposition

4. Results

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Characteristics Between Inter-Urban and Rural-to-Urban Migrants

4.1.1. Individual Characteristics

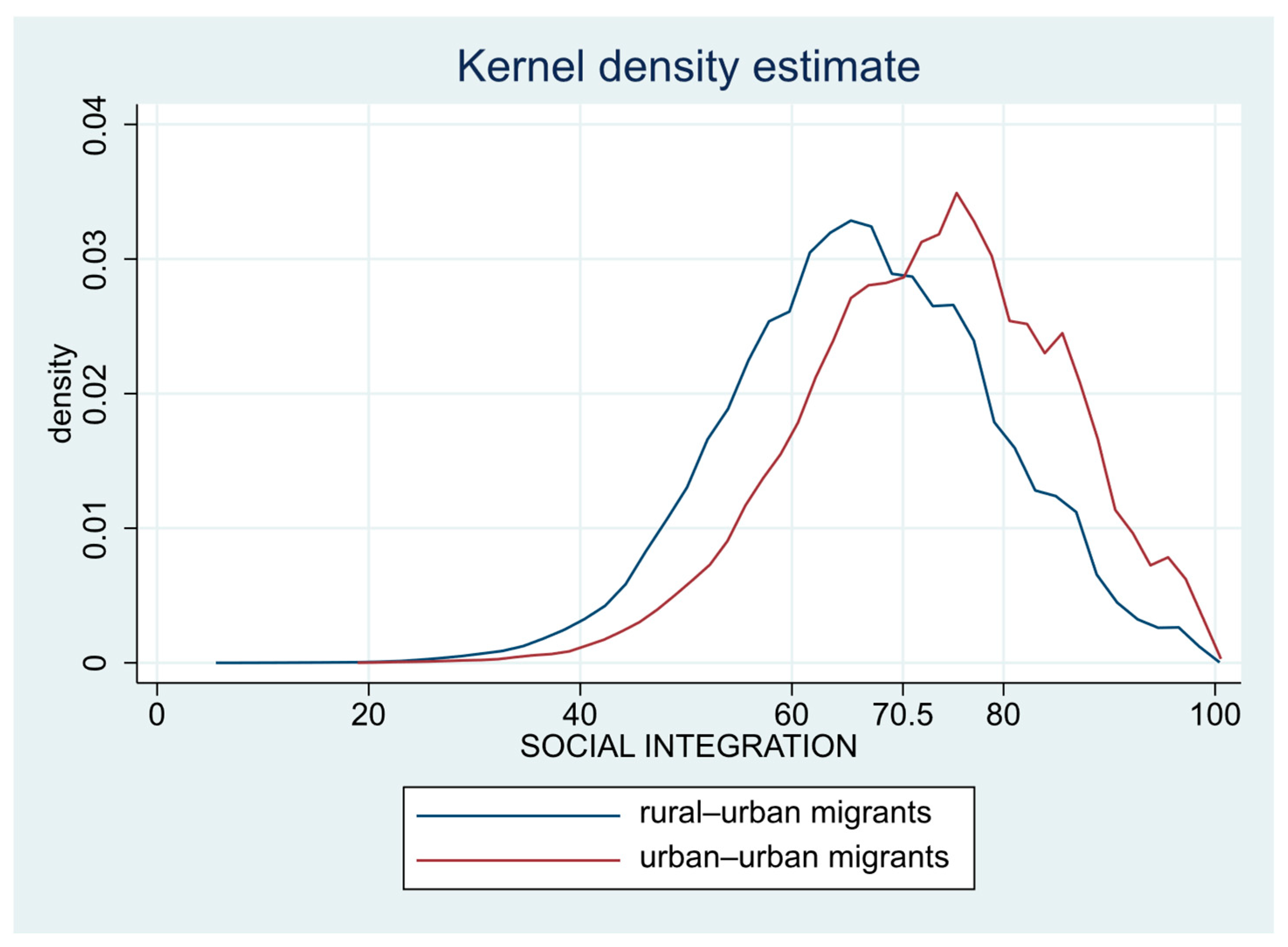

4.1.2. Comparison of Social Integration Levels Between Rural–Urban and Urban–Urban Migrants

4.1.3. Cross-Analysis of Individual Characteristics and Social Integration

4.2. Regression Analysis of Factors Influencing Social Integration

4.3. Robust Test

4.4. Decomposition of Intergroup Differences in Social Integration Between Urban–Urban and Rural–Urban Migrants

4.5. Analysis of Impact Changes and Difference Decomposition Under Different Social Integration Level Distributions

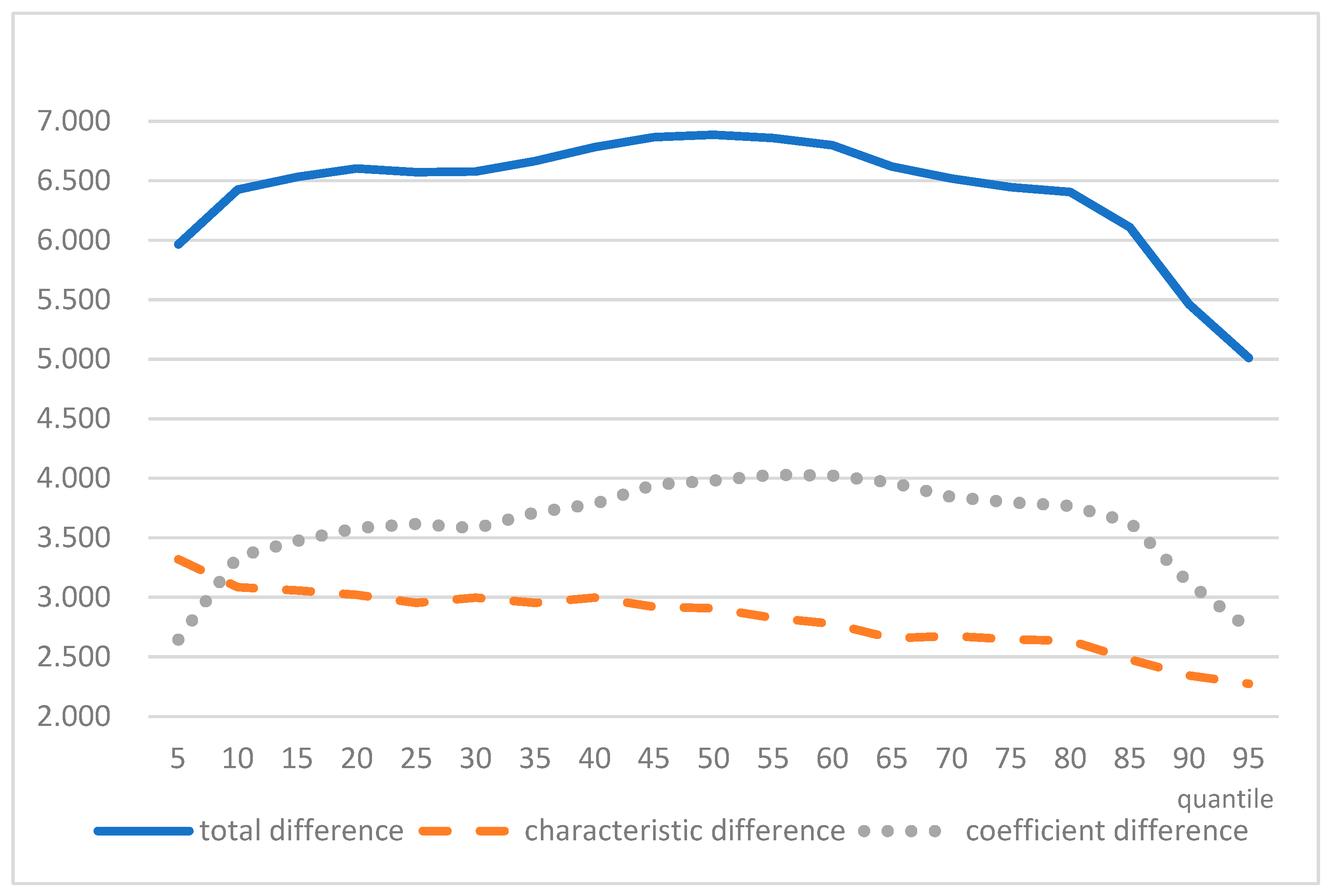

4.6. Decomposition of Social Integration Level Differences at Different Quantiles of the Migrants

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Policy Implications

5.3. Limitations

5.4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, C.; Chen, J. The Impact of the Dual “Hukou Wall” on the Citizenization of Migrant Workers. Economist 2009, 10, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Wang, G. Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Social Integration on the Willingness of Migrant Workers to Become Citizens—Based on the 2016 China Migrant Population Dynamic Monitoring Survey. Northwest Popul. J. 2021, 42, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Urban-Rural Segmentation, Economic Development and Income Integration of Rural-Urban Migrants. Popul. J. 2011, 5, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Research on the Social Integration of China’s Migrant Population. Soc. Sci. China 2015, 2, 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Zheng, X.; Shangguan, S. The Impact of Social Networks on the Social Integration of Migrant Population—Based on Empirical Analysis of China Labor Dynamics Survey. South. China Popul. 2021, 36, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Goldlust, J.; Richmond, A.H. A Multivariate Model of Immigrant Adaptation. Int. Migr. Rev. 1974, 8, 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.E. Human Migration and the Marginal Man. Am. J. Sociol. 1928, 33, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallen, H.M. Cultural Pluralism and the American Idea: An Essay in Social Philosophy; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1956; ISBN 9781512812527. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.; Zhou, M. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 1993, 530, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurh, W.M.; Kim, K.C. Adhesive Sociocultural Adaptation of Korean Immigrants in the U.S.: An Alternative Strategy of Minority Adaptation. Int. Migr. Rev. 1984, 18, 188–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gans, H.J. Second-generation Decline: Scenarios for the Economic and Ethnic Futures of the Post-1965 American Immigrants. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1992, 15, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K. Investigation, Analysis and Reflection on the Urban Adaptability of Migrant Workers. Soc. Sci. Res. 1995, 5, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Lei, K. Analysis of the Structure, Status Quo and Influencing Factors of Social Integration of New Urban Immigrants. Sociol. Stud. 2008, 5, 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L. On the Urban Adaptation of Migrant Workers. Jianghai Acad. J. 2002, 6, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. From Isolation, Selective Integration to Assimilation: Theoretical Reflections on the Social Integration of Migrant Population. Popul. Res. 2009, 33, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X. “Settling Down”?—Social Adaptation of Rural Migrants from the Three Gorges. Sociol. Res. 2004, 19, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. Measurement and Theoretical Reflection on the Social Integration of Migrant Population. Popul. Res. 2012, 36, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T.W. Investment in Human Capital. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, E.F. Education, Economic Growth, and Gaps in Information. J. Polit. Econ. 1962, 70, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education, 3rd ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Mincer, J. Schooling, Experience, and Earnings. Human Behavior & Social Institutions; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Ren, T.; Liu, T. Training, Skill-Upgrading and Settlement Intention of Migrants: Evidence from China. Urban Stud. 2018, 56, 2779–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Tian, F. Intergenerational Comparison of Social Integration of Migrant Workers in China. Society 2012, 32, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, C. Migrant Workers’ Wages: Human Capital, Social Capital, Enterprise System or Social Environment?—A Model for Determining Migrant Workers’ Wages in the Pearl River Delta. Sociol. Res. 2007, 6, 114–137. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, S.; Qing, B.; Tang, J. Occupational Training and Urban Integration of Migrant Population—Based on the Analysis of China Rural Residents Comprehensive Survey. Urban Dev. Res. 2020, 27, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Human Capital and Social Integration of Migrant Population. Popul. Res. 2016, 40, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Wei, C.; Tong, D. Human Capital, Social Support and Social Integration of Migrant Population—Taking Beijing as an Example. Popul. Dev. 2020, 26, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Yue, Z. Research on the Status Quo and Influencing Factors of Migrant Workers’ Social Support Network. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2007, 1, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, G. Human Capital Return and Social Integration of Migrant Population in China. Soc. Sci. China 2012, 4, 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Labor Migration and Earnings Differences: The Case of Rural China. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 1999, 47, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, G.J. Ethnic Capital and Intergenerational Mobility. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 107, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, F. Social Capital and Migration: How Do Rural Migrants Integrate into Urban Society in China. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2014, 23, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, H. Assimilation, Ethnic Stratification, or Selective Acculturation? Recent Theories of the Integration of Immigrants and the Model of Intergenerational Integration. Sociologica 2010, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.; Song, L. The Rural-Urban Divide: Economic Disparities and Interactions in China; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; ISBN 019168497X. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, I.; Smyth, R. Who Wants Safer Cities? Perceptions of Public Safety and Attitudes to Migrants among China’s Urban Population. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 2008, 28, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C. China on the Move: Migration, the State, and the Household; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2007; ISBN 0203937376. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Shi, R. Institutional Constraints, Human Capital, and Employment Differentiation of Migrant Population: An Empirical Analysis Based on the 2015 National Migrant Population Dynamic Data. Lanzhou Acad. J. 2020, 11, 150–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Yin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, Q. Spatial Distribution, Flowing Rules and Forming Mechanism of Inter-Cities Floating Population in China. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 926–936. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Liu, M. Research on the Influence of Education Level on the Employment Quality of Migrant Population. Popul. J. 2023, 45, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Vontroba, J.; Balcar, J.; Šimek, M. Commuting Pays off: Evidence on Wage Returns to Inter-Urban and Intra-Urban Commuting. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2020, 28, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Huang, G.; Xue, D. Spatial Pattern and Influencing Mechanism of Social Integration of Migrants in Chinese Cities. ACTA Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 2474–2493. [Google Scholar]

- Mouate, O.; Travers, M. The Impact of Cultural Amenities on Inter-Urban Location: A Discrete Choice Experiment on French Students. J. Cult. Econ. 2024, 48, 575–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Zhang, L. Analysis of the Social Integration Status of Ethnic Minority Migrant Population—Based on the 2017 National Migrant Population Dynamic Monitoring Data. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 42, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ren, Y. The Impact of Household Migration on the Social Integration of Migrant Population and Its Heterogeneity Analysis. Popul. Dev. 2021, 27, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Oaxaca, R. Male-Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets. Int. Econ. Rev. 1973, 14, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J.A.F.; Mata, J. Counterfactual Decomposition of Changes in Wage Distributions Using Quantile Regression. J. Appl. Econ. 2005, 20, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Rural Compulsory Education in China: Status Quo, Problems and Solutions. China Rural Econ. 2023, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Poverty Governance and Unequal Distribution of Compulsory Education Resources. J. South China Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 50, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.W.; Zhang, L. The Hukou System and Rural-Urban Migration in China: Processes and Changes. China Q. 1999, 160, 818–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X. Labor Market Outcomes and Reforms in China. J. Econ. Perspect. 2012, 26, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Wage Inequality and the Hukou System in China. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on E-Education, E-Business, E-Management and E-Learning, Tokyo, Japan, 10–13 January 2019; pp. 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T. Segmentation and Increasing Marginal Returns: Characteristics and Trends in Individual Education Returns in Chinese Cities—A Multilevel Analysis Based on CGSS2005. Wuhan Univ. J. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 66, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Pipere, A.; Mārtinsone, K. Metamodernism and Social Sciences: Scoping the Future. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlovič, R.; Matlovičová, K. The Metamodern Shift in Geographical Thought: Oscillatory Ontology and Epistemology, Post-Disciplinary and Post-Paradigmatic Perspectives. Folia Geogr. 2025, 67, 22. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Variable | Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Human Capital | Education level | Measured in years |

| Self-rated health | 1 = Unable to take care of oneself, 4 = Healthy | |

| Duration of migration | Calculated as 2017-Year left registered residence | |

| Total work experience | Calculated as 2017-Year of birth- 6-years of education | |

| Personal Characteristics | Gender | 0 = Female, 1 = Male |

| Marital status | 0 = Unmarried, 1 = Married | |

| Family Background | Family members accompanying migration | 0 = No, 1 = Yes |

| Parental migration experience | 0 = No, 1 = Yes | |

| Occupational Status | Industry type | 1 = Primary industry, 2 = Secondary industry, 3 = Tertiary industry |

| Unit type | 1 = No unit, 2 = Individual business owner, 3 = Private enterprise, 4 = State-owned enterprise | |

| Economic Integration | Monthly net income (log) | |

| Perception of economic hardship | 0 = Yes, 1 = No | |

| Behavioral Adaptation | Adherence to customs | 1 = Strongly agree, 4 = Strongly disagree |

| Hygiene habits | 1 = Strongly agree, 4 = Strongly disagree | |

| Identity | Willingness to settle down | 0 = Unwilling, 1 = Undecided, 2 = Willing |

| Sense of belonging | 1 = Strongly disagree, 4 = Strongly agree | |

| Psychological Integration | Willingness to integrate | 1 = Strongly disagree, 4 = Strongly agree |

| Perceived acceptance by locals | 1 = Strongly disagree, 4 = Strongly agree | |

| Perceived discrimination by locals | 1 = Strongly agree, 4 = Strongly disagree |

| Variables | Overall | Urban–Urban | Rural–Urban | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Mean (Std) | Percentage | Mean (Std) | Percentage | Mean (Std) | ||

| Sex | Male | 50.69% | 67.980 (12.606) | 49.69% | 72.735 (12.194) | 51.03% | 66.369 (12.334) |

| Female | 49.31% | 68.484 (12.592) | 50.31% | 73.251 (11.913) | 48.97% | 66.783 (12.389) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 81.04% | 68.229 (12.676) | 80.29% | 73.281 (11.989) | 81.3% | 66.487 (12.437) |

| Unmarried | 18.96% | 68.220 (12.281) | 19.71% | 71.811 (12.264) | 18.7% | 66.935 (12.030) | |

| Family members | With | 88.56% | 68.283 (12.663) | 87.48% | 73.261 (12.018) | 88.93% | 66.575 (12.426) |

| Without | 11.44% | 67.802 (12.111) | 12.52% | 71.109 (12.165) | 11.07% | 66.540 (11.851) | |

| Parents’ migrating experiences | With | 21.28% | 68.101 (12.373) | 16.83% | 72.437 (12.027) | 22.76% | 66.987 (12.220) |

| Without | 78.72% | 68.329 (12.677) | 83.17% | 73.187 (12.052) | 77.24% | 66.511 (12.423) | |

| Industry | Primary | 1.47% | 69.188 (12.644) | 1.2% | 74.214 (11.305) | 1.56% | 67.877 (12.656) |

| Secondary | 30.98% | 67.698 (12.655) | 31.05% | 72.372 (12.276) | 30.94% | 66.142 (12.396) | |

| Tertiary | 67.54% | 68.157 (12.569) | 67.75% | 72.915 (12.012) | 67.5% | 66.580 (12.349) | |

| Unit | No unit | 9.66% | 65.158 (12.520) | 5.11% | 69.633 (12.328) | 11.16% | 64.467 (12.409) |

| Self-employed | 46.21% | 66.980 (12.385) | 35.29% | 71.093 (12.108) | 49.78% | 66.003 (12.246) | |

| Private enterprise | 34.68% | 69.335 (12.573) | 42.09% | 73.735 (11.881) | 32.26% | 67.451 (12.393) | |

| Public enterprise | 9.46% | 71.406 (12.600) | 17.51% | 74.704 (11.904) | 6.80% | 68.568 (12.496) | |

| Variable | Entire Sample | Urban–Urban Migration | Rural–Urban Migration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | Mean (Standard Deviation) | Mean (Standard Deviation) | |

| Years of Education | 10.472 (3.444) | 12.410 (3.311) | 9.809 (3.232) |

| Self-Rated Health | 3.790 (0.472) | 3.794 (0.466) | 3.788 (0.474) |

| Total Work Experience | 20.181 (12.832) | 19.653 (13.779) | 20.365 (12.489) |

| Migration Duration (Years) | 11.125 (7.883) | 10.862 (8.188) | 11.211 (7.774) |

| Variable | Model 1 (Entire Sample) | Model 2 (Urban–Urban) | Model 3 (Rural–Urban) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban–Urban Migrant | 3.875 *** (0.10) | ||

| Education | 0.807 *** (0.02) | 0.944 *** (0.03) | 0.758 *** (0.02) |

| Self-Rated Health | 3.421 *** (0.10) | 3.792 *** (0.21) | 3.319 *** (0.12) |

| Migration Duration | 0.045 *** (0.01) | 0.042 *** (0.01) | 0.046 * (0.01) |

| Total Work Experience | 0.024 *** (0.01) | 0.048 *** (0.01) | 0.018 * (0.01) |

| Gender (Male = 1) | −0.426 *** (0.08) | −0.562 *** (0.16) | −0.372 *** (0.10) |

| Marital Status (Married = 1) | −0.055 (0.16) | −0.082 (0.32) | −0.067 (0.19) |

| Accompanying Family Members (Yes = 1) | 1.117 *** (0.19) | 2.334 *** (0.36) | 0.644 ** (0.22) |

| Parental Migration Experience (Yes = 1) | −0.442 *** (0.10) | −0.581 *** (0.21) | −0.393 *** (0.12) |

| Secondary Industry | −3.698 *** (0.35) | −2.917 *** (0.74) | −3.840 *** (0.40) |

| Tertiary Industry | −2.858 *** (0.35) | −1.695 * (0.73) | −3.122 *** (0.40) |

| Self-Employed | 0.585 *** (0.14) | 0.658 (0.37) | 0.628 *** (0.16) |

| Private Enterprise | 1.505 *** (0.15) | 1.808 *** (0.37) | 1.409 *** (0.17) |

| State-Owned Enterprise | 1.729 *** (0.19) | 1.613 (0.40) | 1.816 *** (0.23) |

| Constant | 45.935 *** (0.58) | 44.180 (1.25) | 47.547 *** (0.66) |

| N | 92,397 | 23,051 | 69,346 |

| R2 | 0.103 | 0.083 | 0.052 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.102 | 0.082 | 0.052 |

| Before Matching | After Matching | After Matching | After Matching | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1st Matching) | (2nd Matching) | (3rd Matching) | ||

| Urban–Urban Migrant | 3.875 *** | 3.901 *** | 3.564 *** | 3.799 *** |

| (0.10) | (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.10) | |

| Education | 0.807 *** | 0.892 *** | 0.866 *** | 0.796 *** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Self-Rated Health | 3.421 *** | 3.911 *** | 3.402 *** | 2.655 *** |

| (0.10) | (0.11) | (0.08) | (0.09) | |

| Migration Duration | 0.045 *** | 0.061 *** | 0.016 * | 0.056 *** |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.00) | |

| Total Work Experience | 0.024 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.057 *** | 0.009 # |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| Gender (Male = 1) | −0.426 *** | −0.967 *** | −1.170 *** | −0.148 # |

| (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.08) | |

| Marital Status (Married = 1) | −0.055 | 0.182 | −1.103 *** | −0.434 ** |

| (0.16) | (0.16) | (0.16) | (0.16) | |

| Accompanying Family Members (Yes = 1) | 1.117 *** | 1.014 *** | 1.114 *** | 0.705 *** |

| (0.19) | (0.18) | (0.19) | (0.19) | |

| Parental Migration Experience (Yes = 1) | −0.442 *** | −0.321 ** | 0.862 *** | −0.939 *** |

| (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.10) | |

| Secondary Industry | −3.698 *** | −2.546 *** | −5.327 *** | −4.397 *** |

| (0.35) | (0.35) | (0.38) | (0.36) | |

| Tertiary Industry | −2.858 *** | −2.052 *** | −4.521 *** | −3.662 *** |

| (0.35) | (0.35) | (0.37) | (0.36) | |

| Self-Employed | 0.585 *** | 1.020 *** | 0.459 ** | 0.858 *** |

| (0.14) | (0.14) | (0.15) | (0.15) | |

| Private Enterprise | 1.505 *** | 2.553 *** | 1.051 *** | 0.750 *** |

| (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.16) | (0.15) | |

| State-Owned Enterprise | 1.729 *** | 2.577 *** | 2.178 *** | 1.792 *** |

| (0.19) | (0.18) | (0.19) | (0.19) | |

| Constant | 45.935 *** | 40.979 *** | 48.259 *** | 50.595 *** |

| (0.58) | (0.66) | (0.57) | (0.55) | |

| N | 92,397 | 92,256 | 91,993 | 91,816 |

| R2 | 0.103 | 0.091 | 0.103 | 0.088 |

| adj. R2 | 0.102 | 0.090 | 0.103 | 0.088 |

| Social Integration Level Difference | ||

|---|---|---|

| Difference Value (Urban–Urban vs. Rural–Urban) | Percentage | |

| Total Difference | 6.302 *** | 100 |

| Characteristic Effect | 2.417 *** | 38.35 |

| Coefficient Effect | 3.885 *** | 61.65 |

| Variable | OLS | 10th Quantile | 25th Quantile | 50th Quantile | 75th Quantile | 90th Quantile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban–Urban Migrant | 3.875 *** (0.10) | 3.917 *** (0.17) | 4.045 *** (0.15) | 4.333 *** (0.12) | 3.970 *** (0.14) | 3.277 *** (0.16) |

| Education | 0.807 *** (0.02) | 0.915 *** (0.03) | 0.850 *** (0.02) | 0.822 *** (0.02) | 0.787 *** (0.02) | 0.713 *** (0.03) |

| Self-Rated Health | 3.421 *** (0.10) | 3.398 *** (0.18) | 3.177 *** (0.15) | 3.393 *** (0.12) | 3.736 *** (0.14) | 3.753 *** (0.16) |

| Migration Duration | 0.045 *** (0.01) | 0.020 * (0.01) | 0.033 *** (0.01) | 0.049 *** (0.01) | 0.074 *** (0.01) | 0.049 *** (0.01) |

| Total Work Experience | 0.024 *** (0.01) | 0.027 ** (0.01) | 0.021 ** (0.01) | 0.021 ** (0.01) | 0.030 *** (0.01) | 0.037 *** (0.01) |

| Gender (Male = 1) | −0.426 *** (0.08) | −0.618 *** (0.14) | −0.523 *** (0.12) | −0.315 *** (0.10) | −0.370 *** (0.12) | −0.447 *** (0.13) |

| Marital Status (Married = 1) | −0.055 (0.16) | −0.034 (0.29) | 0.148 (0.24) | 0.035 (0.20) | −0.369 (0.23) | −0.440 (0.26) |

| Accompanying Family (Yes = 1) | 1.117 *** (0.19) | 1.300 *** (0.33) | 0.927 *** (0.28) | 1.146 *** (0.23) | 1.489 *** (0.27) | 1.367 *** (0.30) |

| Parental Migration (Yes = 1) | −0.442 *** (0.10) | −0.397 * (0.18) | −0.587 *** (0.15) | −0.435 *** (0.12) | −0.399 *** (0.14) | −0.350 ** (0.17) |

| Secondary Industry | −3.698 *** (0.35) | −3.934 *** (0.62) | −4.102 *** (0.52) | −3.694 *** (0.42) | −3.539 *** (0.50) | −3.799 *** (0.57) |

| Tertiary Industry | −2.858 *** (0.35) | −3.208 *** (0.61) | −3.070 *** (0.51) | −2.824 *** (0.42) | −2.682 *** (0.49) | −3.139 *** (0.56) |

| Self-Employed | 0.585 *** (0.14) | 0.368 (0.25) | 0.889 *** (0.21) | 0.747 *** (0.17) | 0.718 *** (0.20) | 0.441 * (0.23) |

| Private Enterprise | 1.505 *** (0.15) | 1.458 *** (0.27) | 1.905 *** (0.22) | 1.729 *** (0.18) | 1.494 *** (0.22) | 1.303 *** (0.25) |

| State-Owned Enterprise | 1.729 *** (0.19) | 1.382 *** (0.33) | 1.921 *** (0.28) | 1.979 *** (0.23) | 2.015 *** (0.27) | 1.671 *** (0.31) |

| Constant | 45.935 *** (0.58) | 30.058 *** (1.01) | 38.621 *** (0.85) | 45.581 *** (0.69) | 52.423 *** (0.82) | 61.403 *** (0.93) |

| N | 92,397 | 92,397 | 92,397 | 92,397 | 92,397 | 92,397 |

| Quantile (%) | Total Difference | Characteristic Difference | Coefficient Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Percentage | Value | Percentage | ||

| 5 | 5.965 | 3.319 | 55.64% | 2.646 | 44.36% |

| 10 | 6.426 | 3.084 | 47.99% | 3.342 | 52.01% |

| 15 | 6.532 | 3.057 | 46.80% | 3.475 | 53.20% |

| 20 | 6.603 | 3.021 | 45.75% | 3.582 | 54.25% |

| 25 | 6.571 | 2.954 | 44.96% | 3.617 | 55.04% |

| 30 | 6.578 | 2.998 | 45.58% | 3.580 | 54.42% |

| 35 | 6.665 | 2.954 | 44.32% | 3.711 | 55.68% |

| 40 | 6.782 | 2.998 | 44.21% | 3.784 | 55.79% |

| 45 | 6.866 | 2.920 | 42.53% | 3.946 | 57.47% |

| 50 | 6.887 | 2.907 | 42.21% | 3.980 | 57.79% |

| 55 | 6.858 | 2.828 | 41.24% | 4.030 | 58.76% |

| 60 | 6.799 | 2.777 | 40.84% | 4.022 | 59.16% |

| 65 | 6.619 | 2.655 | 40.11% | 3.964 | 59.89% |

| 70 | 6.518 | 2.675 | 41.04% | 3.843 | 58.96% |

| 75 | 6.445 | 2.647 | 41.07% | 3.798 | 58.93% |

| 80 | 6.405 | 2.636 | 41.16% | 3.769 | 58.84% |

| 85 | 6.109 | 2.478 | 40.56% | 3.631 | 59.44% |

| 90 | 5.460 | 2.342 | 42.89% | 3.118 | 57.11% |

| 95 | 5.012 | 2.275 | 45.39% | 2.737 | 54.61% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, T.; Ren, J. The Differential Impact of Human Capital on Social Integration Among Rural–Urban and Urban–Urban Migrants in China. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080292

Xu T, Ren J. The Differential Impact of Human Capital on Social Integration Among Rural–Urban and Urban–Urban Migrants in China. Urban Science. 2025; 9(8):292. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080292

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Tao, and Jiyan Ren. 2025. "The Differential Impact of Human Capital on Social Integration Among Rural–Urban and Urban–Urban Migrants in China" Urban Science 9, no. 8: 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080292

APA StyleXu, T., & Ren, J. (2025). The Differential Impact of Human Capital on Social Integration Among Rural–Urban and Urban–Urban Migrants in China. Urban Science, 9(8), 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9080292