1. Introduction

Form-based codes (FBCs) are regulatory tools used in urban planning to shape the physical form of the built environment, focusing on design and spatial relationships rather than land use alone [

1,

2,

3]. Unlike conventional zoning codes that emphasize density and function, FBCs prioritize the visual and experiential qualities of places—such as building placement, façade design, and the relationship between private and public space. They offer a more precise and reliable framework to preserve valued aspects of the built environment and mitigate unwanted changes in urban form [

4]. By providing a structured framework for preserving neighborhood character, guiding new development, and enhancing walkability and social cohesion, FBCs are increasingly adopted across U.S. cities [

5] (p. 1), [

6]. This shift is particularly relevant in fostering a strong sense of place (SoP), as research has shown that the physical form of urban environments significantly influences residents’ emotional attachment, place identity, and satisfaction [

7,

8,

9].

Given earlier research, defining the grammar of the built environment in a way that enhances perceived residential satisfaction and SoP is of crucial importance [

10,

11]. In this study, residential satisfaction is understood as an expression of sense of place, particularly through the dimensions of place attachment, identity, and dependence. FBCs provide a regulatory framework to maintain the aesthetic, functional, and social integrity of neighborhoods by preserving elements that residents value while mitigating undesirable changes [

12,

13]. By emphasizing design quality, walkability, and mixed-use developments, FBCs can enhance place attachment and foster social interactions within communities [

14,

15,

16]. While FBCs can apply to a range of land uses, this study focuses on their application in residential neighborhoods, where maintaining a high level of satisfaction and place attachment is particularly critical. Failure to integrate such principles into urban planning may lead to a disconnect between residents and their built environment, ultimately eroding SoP and contributing to dissatisfaction [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

Although the theoretical value of FBCs in shaping place quality is well documented [

2,

17,

18], empirical studies that examine how these codes influence subjective place experiences remain scarce—particularly in historically established urban neighborhoods. Most existing research either focuses on New Urbanist developments [

11,

12] or emphasizes morphological coherence over lived experience [

13]. Additionally, few studies adopt a scale-sensitive approach to evaluate how place attachment, identity, and dependence vary across zoning categories and spatial hierarchies [

9,

19]. This study addresses these gaps by offering a multi-scalar framework that integrates regulatory zoning types with validated perceptual metrics to assess the emotional, symbolic, and functional dimensions of sense of place (SoP). By doing so, it provides a novel and transferable methodological lens to assess the experiential performance of form-based regulatory tools in established residential contexts.

This study brings together the interrelated concepts of form-based codes and sense of place (SoP) to examine how regulatory frameworks influence lived experiences and satisfaction in established residential settings. Rather than focusing solely on areas experiencing new development, this study examines how FBCs can be utilized as a proactive tool to sustain SoP in neighborhoods that existed before their adoption. Instead of merely discussing the impact of new developments on neighborhood character, the emphasis is placed on measuring the potential benefits of FBCs in preserving existing satisfaction levels and projecting pathways for further enhancement [

17,

18].

To explore these dynamics, this study evaluates Buffalo’s Green Code—a locally developed form-based zoning ordinance that regulates urban development across the city. Although its name might suggest an environmental emphasis, the Green Code is not centered on ecological principles but instead serves as a comprehensive form-based planning framework. While the code applies city-wide, this research focuses specifically on Elmwood Village, one of Buffalo’s most established residential neighborhoods, to assess how form-based regulation functions within a dense, historically rooted, and socially cohesive urban fabric. Located in central Buffalo, Elmwood Village is widely recognized for its stable residential structure, vibrant street life, and strong sense of community. Its national significance was affirmed when it was selected as one of the ten most livable neighborhoods in the United States by the American Planning Association [

20], based on its cultural vitality and inclusive public realm. The neighborhood also benefits from a long-standing physical and emotional connectedness, partly due to its integration into Frederick Law Olmsted’s parkway system, which enhances both accessibility and spatial continuity [

21]. This legacy of place attachment—passed down through generations—continues to shape local identity and reinforces the area’s social and historical depth [

22]. Given these attributes, Elmwood Village offers a meaningful and context-rich setting in which to investigate how form-based regulations influence sense of place in established residential environments [

23]. By systematically measuring subjective perceptions of place identity, attachment, and neighborhood cohesion, this study seeks to establish whether the implementation of Buffalo’s Green Code aligns with residents’ expectations and contributes to the enhancement of SoP [

11,

13,

16].

This research highlights the reciprocal relationship between FBCs and SoP in U.S. residential settings, emphasizing the importance of integrating subjective experiences into planning practices and policymaking [

24,

25]. It contributes to ongoing discussions about how urban form shapes social and psychological well-being, and how regulatory tools can align with lived experience to foster more meaningful and responsive urban environments [

13,

17]. Within this context, the aim of this paper is to evaluate the extent to which Buffalo’s Green Code enhances the sense of place in an established residential neighborhood through the lived experiences of its residents. Given the aim, the research objectives are as follows:

To assess perceptions of place identity, attachment, and neighborhood cohesion in Elmwood Village.

To compare SoP satisfaction across Green Code zoning typologies (mixed-use, residential, single-family).

To examine spatial variations in SoP using a multi-scalar framework (building, street, neighborhood).

To identify spatial patterns in satisfaction levels.

To explore how form-based regulatory tools align with lived experience in the built environment.

In doing so, this study also offers a transferable framework for analyzing how form-based regulations relate not only to the organization of physical space, but also to the symbolic, emotional, and social meanings embedded in place-based experience [

24,

25].

3. Research Gap

Understanding how built environments influence emotional, symbolic, and functional attachment to place has long been a central concern in both environmental psychology and urban planning. Scholars such as Relph [

7] and Tuan [

8] emphasize that place is not merely a physical location but a socially and emotionally constructed space imbued with meaning through human experience. According to Altman and Low [

26], sense of place (SoP) encompasses dimensions such as place attachment, place identity, and place dependence—constructs that have been operationalized and empirically validated in various contexts [

39,

40].

In the planning field, the emergence of form-based codes (FBCs) marks a shift from use-based to design-oriented zoning practices that prioritize the spatial and experiential quality of urban environments. As Parolek et al. [

2] argue, FBCs regulate the public realm through control of building form, frontage, and block structure, with the explicit goal of shaping coherent, human-scale neighborhoods. Talen [

6] further emphasizes that FBCs aim to restore the legibility and walkability of urban form, which are widely recognized as preconditions for fostering a stronger SoP.

Although the conceptual basis of form-based design and its links to place attachment have been widely discussed, empirical investigations remain sparse—particularly those that examine the lived, emotional, and symbolic implications of zoning tools like FBCs across different spatial contexts. A critical review of the existing literature reveals four key patterns: First, a significant portion of prior research has focused on the formal or morphological impacts of FBCs. For example, Talen [

6] evaluates how FBCs improve spatial legibility and walkability, while Carmona [

41] extends this by linking public space quality with the psychological affordances of urban design. However, these works primarily address design intentions and visual coherence, often neglecting how such interventions translate into subjective meanings or affective bonds with place (see also [

2,

42]).

Second, when perceptual or emotional dimensions are examined, they are often limited to new developments. Kim and Kaplan [

11] explore place satisfaction in Kentlands, a New Urbanist neighborhood, yet their findings offer little insight into how form-based principles perform in long-established, socially layered contexts. Similarly, works such as Nasar & Julian [

43] and Brown et al. [

16] confirm associations between design coherence and satisfaction, but fall short in capturing the temporal depth of place identity rooted in memory and continuity.

Third, recent conceptual work by Mehaffy et al. [

13], Kashef & El-Shafie [

34], and Marshall [

37] highlights the symbolic aspirations of FBCs. These authors argue that well-crafted design codes can foster symbolic resonance and shared identity. Yet these claims are largely unverified empirically, particularly in relation to everyday resident experiences and across multiple scales. Moreover, as Stevens [

44] and Hamilton-Baillie [

45] note, over-coding and excessive design prescription may in fact limit spatial spontaneity and reduce affective engagement, especially at the street level.

Fourth, scale-sensitivity remains underexplored. Although Marshall [

30] points out that FBCs operate across scales—from lot to neighborhood—few studies examine how SoP varies accordingly. Quinn-Smith [

32] and Southworth [

46] show that street-scale experiences are particularly vulnerable to regulatory misalignment, with users often reporting dissatisfaction despite formal improvements. Such findings suggest that regulatory precision does not automatically ensure perceptual performance.

Additionally, the role of mixed-use typologies in shaping place experience is frequently oversimplified. While mixed-use areas are often praised for their diversity, vitality, and visual richness [

15,

28], several studies [

47,

48] caution that such zones can also produce feelings of disconnection, noise stress, or transience—factors that hinder emotional and functional attachment. Yet these dimensions are rarely addressed in FBC evaluations, which tend to emphasize formal compliance over lived experience.

Further, the integration of quantitative place-based metrics into planning research remains limited. As Lewicka [

9] argues, place attachment is not simply a spatial byproduct, but a psychological process shaped by time, interaction, and socio-cultural dynamics. Friedmann [

49] and Seamon [

50] reinforce this by showing that meaningful places arise through habitual use and narrative coherence, aspects that are difficult to capture through conventional zoning logic. In summary, the following research gaps persist:

A lack of empirical research linking FBCs with all three dimensions of SoP (identity, attachment, dependence);

Minimal attention to spatial scale, despite clear evidence that place perception varies significantly between building, street, and neighborhood levels;

Underrepresentation of established neighborhoods where FBCs are retroactively applied rather than designed from the outset;

Limited integration of perceptual and symbolic indicators into zoning performance evaluation;

An overemphasis on morphological and compliance-based outcomes, at the expense of lived and narrative-based place meanings.

This study addresses these gaps by offering a multi-scalar, empirically grounded assessment of SoP under the Buffalo Green Code. It draws on validated survey instruments, typological zoning analysis, and spatial clustering techniques to evaluate how different zoning categories—mixed-use, multi-family residential, and single-family residential—align with residents’ emotional, symbolic, and functional place experiences. In doing so, it contributes not only to the literature on form-based planning but also to broader debates on how regulatory frameworks influence the formation of meaningful urban environments.

4. Methodology

This study adopts a case study approach to evaluate the effectiveness of Buffalo’s Green Code in fostering sense of place (SoP) across multiple spatial scales within Elmwood Village. To establish the regulatory and spatial context, the methodology first introduces the Buffalo Green Code as the city-wide form-based zoning framework and then situates Elmwood Village as the selected residential case study. Following this contextual foundation, the research proceeds through three main stages: (1) delineating Green Code zoning categories within Elmwood Village, (2) collecting data on SoP through a structured resident survey, and (3) evaluating SoP performance using both descriptive statistical analysis and spatial clustering techniques.

4.1. Buffalo’s Green Code and Elmwood Village

Form-based codes (FBCs) have gained increasing traction in American cities seeking to link urban form with livability and place quality. Buffalo, New York, stands as a prominent example of this shift, having adopted the Buffalo Green Code Unified Development Ordinance (UDO) in February 2017, following two decades of local engagement and planning initiatives [

23,

51]. This code was developed as a city-wide zoning overhaul and is one of the most comprehensive applications of FBCs in the United States, comparable to initiatives in Miami, Denver, and Cincinnati [

52].

The Green Code was designed to align zoning regulations with a form-based, place-sensitive approach to urban design. In other words, the Green Code operates as a form-based code (FBC), regulating physical form rather than land use alone and its provisions for building-to-street relationships and pedestrian-scale design align with FBC principles. It focuses on shaping the built environment through standards governing the relationship between buildings and public spaces, building form and massing, and the structure of blocks and streets, rather than prescribing land uses alone [

23]. As such, it reflects a paradigmatic shift from traditional zoning to a vision that integrates urban form with the lived experience of place.

The Green Code organizes Buffalo into a layered system of neighborhood, district, and corridor zones, each addressing different scales of urban design [

23]. These zoning categories align with macro- and micro-scale elements of FBCs discussed by Parolek et al. [

2], where neighborhood-scale zones shape broader spatial frameworks, and building-scale elements define granular built form characteristics. In this research, attention is focused on the neighborhood zones.

Table 2 introduces the city-wide neighborhood zoning codes.

One of the most prominent testing grounds for this above-described policy has been Elmwood Village, often regarded as one of Buffalo’s most emblematic neighborhoods. Elmwood Village is located in the heart of Buffalo, New York, just northwest of Downtown. Centered along Elmwood Avenue, the neighborhood stretches roughly from North Street in the south to Forest Avenue in the north, and is bordered by Richmond Avenue to the west and Delaware Avenue to the east. Its location within Buffalo is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Green Code implementation in Elmwood was seen both as a means to preserve existing character—particularly its walkable streets, traditional architecture, and human-scale development—and as a mechanism to guide future growth [

33,

34,

35]. Community members largely welcomed the change, viewing it as a way to protect the social and spatial fabric they value [

35].

Amongst the given neighborhood types in

Table 2, this paper specifically focusses on the neighborhood types that are available within Elmwood Village.

Table 3 (see below) illustrates the six Green Code neighborhood zones that are present within Elmwood Village. These are categorized for the purposes of comparative evaluation of sense of place (SoP) across three broader typological groups: mixed-use, residential, and single-family. The N-2C (Mixed-Use Center) and N-2E (Mixed-Use Edge) zones represent the mixed-use category, with N-2C supporting higher-intensity development at central nodes and N-2E functioning as a transitional buffer with moderate-scale commercial and residential integration. In the residential category, N-2R and N-3R zones allow for a variety of housing types yet differ in density and form: N-2R is characterized by compact, higher-density development near mixed-use areas, while N-3R reflects a more moderate, streetcar-era neighborhood structure with larger lots and lower unit intensity. Finally, N-4-30 and N-4-50 define the single-family category, both intended for detached houses, with the key distinction being lot size—N-4-30 accommodates smaller, more compact parcels, whereas N-4-50 is oriented toward larger-lot, lower-density suburban fabric. Together, these six zoning types capture the spectrum of urban forms present in Buffalo’s neighborhood planning approach. These classifications form the structural basis for analysis in the subsequent methodology section.

4.2. Defining Green Code Areas in Elmwood Village

Focusing on the neighborhood zones designated by the BGC, this study limits its scope to those zones located within Elmwood Village. To align the spatial framework with survey implementation, Elmwood Village was first divided into individual street-segment blocks, as explained above. These blocks were then overlaid with the official Green Code zoning map to identify the zoning designation of each segment. In cases where a block spanned more than one zone, it was excluded to ensure classification robustness. This process resulted in 230 eligible street-segment blocks, representing six BGC zoning types (as identified in

Table 3). The majority of Elmwood Village falls under the N-2R Residential zone.

Due to the uneven distribution of zoning types across the neighborhood, zones were aggregated into three broader categories to ensure representative sampling for meaningful statistical comparison:

Mixed-use: N-2C, N-2E (27 segments)

Residential: N-2R, N-3R (174 segments)

Single-family: N-4-30, N-4-50 (29 segments)

This grouping was based on both policy logic and sample size thresholds to ensure meaningful comparative analysis. However, it is acknowledged that such aggregation may mask finer spatial distinctions, particularly between closely related residential types (e.g., N-2R vs. N-3R). However, these categories reflect meaningful variations in land use intensity and urban form while enabling statistically valid comparisons across groups (each with >15 samples), while maintaining fidelity to the original zoning framework.

Figure 2 maps these three code categories within the study area. Subsequent analysis of SoP is based on these three categories.

4.3. Evaluating Sense of Place in Elmwood Village

To evaluate SoP, an online structured questionnaire was developed, targeting the three key dimensions of SoP: place attachment (PA), place identity (PI), and place dependence (PD). Each dimension was measured using Likert-scale items, adapted from established instruments in the literature (e.g., [

9,

16,

39,

53]). Importantly, for a total of 42 items, each was assessed at three spatial scales—building, street, and neighborhood—to reflect the scalar variability of place perception on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 4 summarizes the survey content and measurement items used for each SoP dimension across scales.

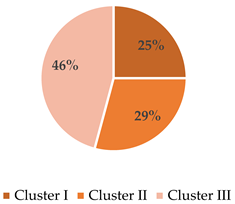

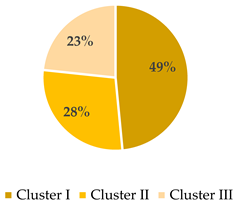

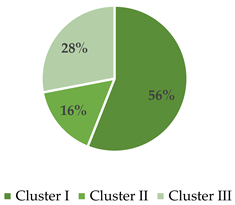

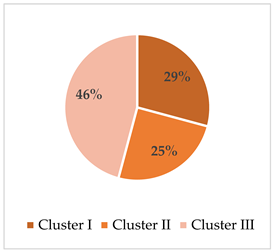

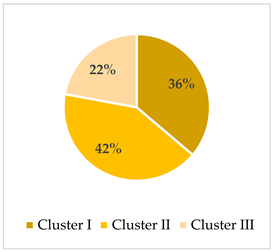

In total, 273 responses were recorded, of which 212 were valid. These responses were linked to specific street segments and grouped under the three Green Code categories identified above (Mixed-Use: 24, Residential: 163, Single-Family: 25). Although the zoning distribution is not uniform, the proportion of responses closely mirrors the actual distribution of zones in Elmwood Village (see

Figure 3) individually, enabling relatively balanced and internally consistent comparative analysis.

4.4. Analytical Framework

The analysis was conducted in two stages:

Step 1—Comparative SoP scores: Mean scores for each SoP indicator were calculated at the building, street, and neighborhood levels. These scores were compared across the three Green Code categories to identify spatial patterns and differences in perceived SoP. Correlations between variables were tested, and linear regressions were used to examine the extent to which each indicator contributed to overall SoP.

Step 2—SoP performance evaluation via cluster analysis: To develop a more nuanced understanding of performance, a scoring system was developed to evaluate Green Code performance in a more integrated manner. This involved a two-step statistical clustering process and employed a two-stage cluster analysis:

Pre-validation via IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 two-step clustering: This step identified the optimal number of clusters per spatial scale based on predictor importance (>0.2), fair model quality, and balanced cluster sizes (largest/smallest < 2 ratio).

K-means clustering for classification: Clusters were characterized by high (4–5), moderate (3–4), and low (<3) levels of SoP. Each level was assigned a satisfaction score (3, 2, 1, respectively).

To enable cross-comparison of SoP performance across zoning categories and spatial scales, each cluster was assigned this satisfaction score on a 3–2–1 ordinal scale: clusters with high mean SoP values (Likert scores ≥ 4.0) were coded as “high satisfaction” (3 points), those with moderate scores (3.0–3.99) as “moderate satisfaction” (2 points), and those with low scores (<3.0) as “low satisfaction” (1 point). This linear point system is a simplified but widely used method in perceptual research and planning studies (e.g., [

16,

54] to translate qualitative satisfaction levels into comparative indices). While more granular weighting could be applied, the 3–2–1 framework offers interpretability and consistency across multi-scalar zones. The aggregated scores serve as a benchmarking tool to highlight which zoning categories perform better in aligning built form with residents’ place-based expectations. A weighted scoring system was developed by multiplying the point values with the percentage of respondents in each cluster per Green Code category. This process was repeated independently for the building, street, and neighborhood scales to understand which spatial level the Green Code most effectively supports. The scoring enabled a comparative performance metric, offering deeper insights into the spatial compatibility of Buffalo’s Green Code with users’ lived experiences.

Overall, within the methodological framework defined above, the Green Code in Elmwood Village represents a form-based code (FBC) approach, where zoning is based not solely on land use but on the physical form of the built environment. The categories used in this study—single-family, residential, and mixed-use—are formal typologies embedded within the Green Code’s FBC framework. Therefore, the SoP outcomes discussed in the following section are directly tied to the spatial and morphological distinctions articulated in the Code.

5. Findings and Analysis

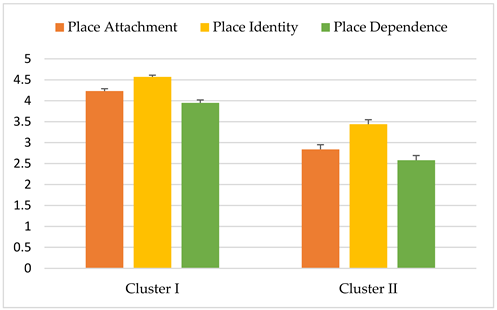

5.1. General Comparative Evaluation of the Satisfaction Scores

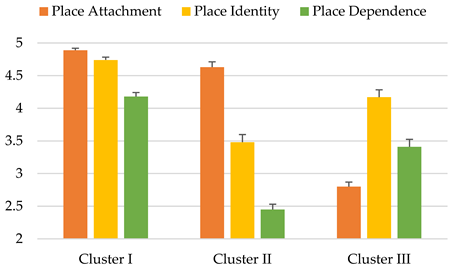

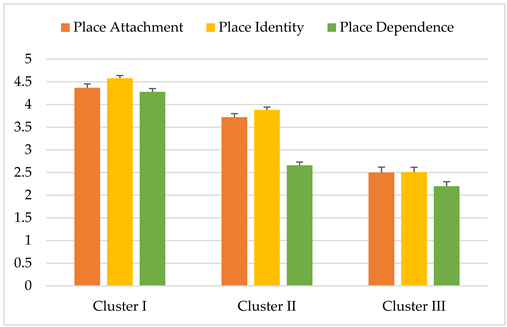

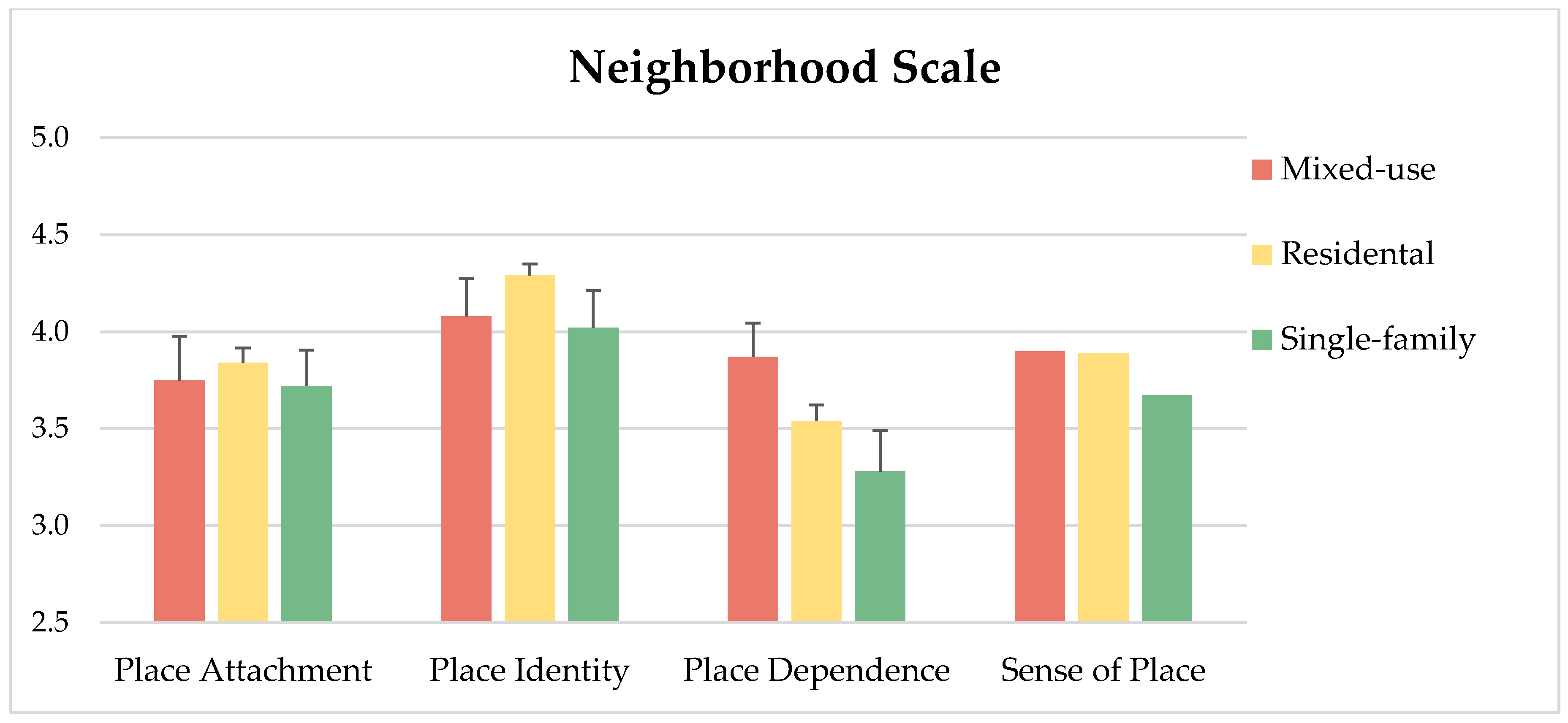

This section compares mean satisfaction scores across the three SoP indicators (place attachment, place identity, and place dependence) at building, street, and neighborhood scales, with differentiation across the three Green Code zoning categories (single-family, residential, and mixed-use zones).

A statistically significant difference was found only in overall SoP scores at the building scale (

p = 0.009). No significant differences were observed among individual SoP parameters (with

p-values ranging from 0.090 to 0.722). As shown in

Figure 4, the building scale consistently yielded higher SoP satisfaction compared to the street and neighborhood scales. Across all indicators, mixed-use areas consistently reported the lowest satisfaction at both building and street scales, while single-family zones reported the highest.

At the street scale, only place dependence in mixed-use zones fell below the satisfaction threshold (<3). In contrast, place attachment and place identity received high scores (>4) from respondents in single-family and residential zones at the building scale, and from residential and mixed-use zones at the neighborhood scale.

5.2. Correlation Analysis: Significance of SoP Indicators

To determine the relative importance of each SoP indicator, Pearson correlation coefficients (R

2) were calculated at all three spatial scales (

Table 5), referencing Cohen’s [

38] standards: low (< 0.3), moderate (0.3–0.5), large (>0.5–0.7), and very large (>0.7). All indicators exceeded the 0.2 threshold, suggesting meaningful relationships. The only exception was place dependence in mixed-use areas at the building scale, with an R

2 of 0.238 and a non-significant

p-value (>0.05). In contrast, strong and very strong correlations (R

2 > 0.7) were found across most categories and scales, especially in residential and single-family zones.

Overall, the analysis revealed distinct spatial dynamics among the three SoP indicators across different Green Code categories. Place identity emerged as the most influential factor in mixed-use areas, showing strong correlation scores across all spatial scales. In residential zones, place attachment was consistently the most significant indicator, particularly evident at the street and neighborhood levels. Place dependence, while generally strong, played a more critical role in single-family areas, especially at the building scale. The only notable low correlation was observed for place dependence in mixed-use areas at the building scale, whereas all other R

2 values exceeded 0.5—with many surpassing 0.7, indicating strong relationships. Notably, at both the street and neighborhood scales, all indicators demonstrated very strong correlations across Green Code categories. Place attachment was especially dominant in single-family areas at these scales, and residential zones showed the highest correlation for place dependence at the neighborhood level. As depicted in

Figure 5, place attachment and identity followed similar patterns across street and neighborhood scales, with place identity being most associated with mixed-use zones.

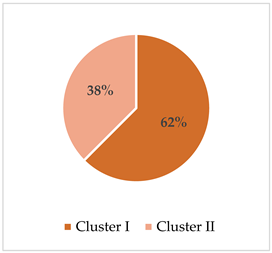

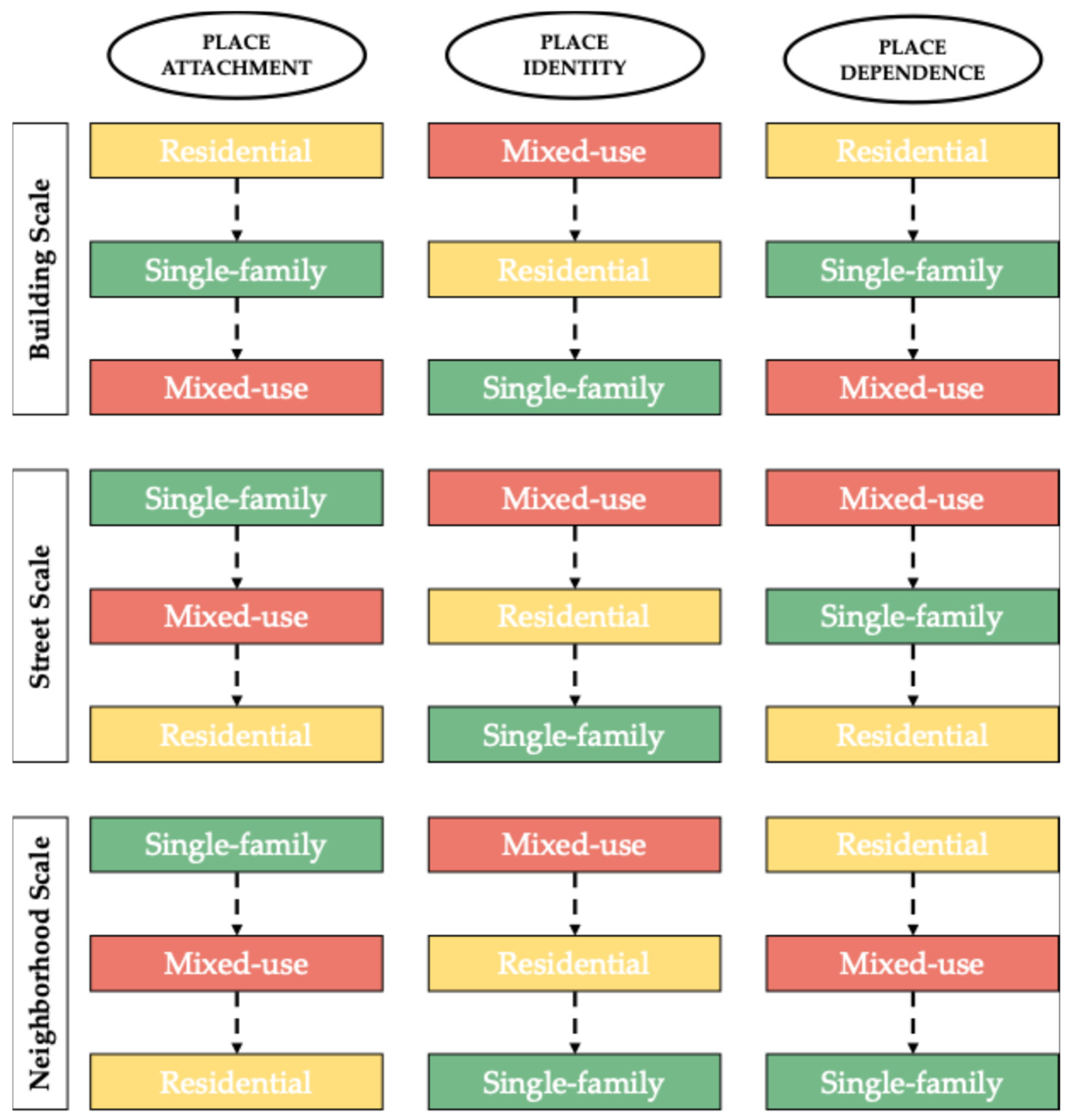

5.3. SoP Performance Mapping Through K-Means Clustering Method

The analysis of sense of place (SoP) performance with its three input variables (place attachment, place identity and place dependence) was carried out using k-means clustering, following a two-step cluster validation procedure in via IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 to identify the optimal number of clusters at each spatial scale. It was the pre-validation stage before applying the k-means clustering to identify the final center clusters for SoP performance evaluation. At this first step, cluster quality (aimed at least fair quality > 0.2), the number of clusters and their identifying characteristics and predictor importance (min > 0.2) have been determined by achieving a successful model where the cluster sizes are not disproportionately distributed. The clustering was conducted independently at the building, street, and neighborhood scales to determine the differentiated effects of the Green Code typologies on residents’ place-based satisfaction.

At the building scale, the most influential predictor was place attachment, with a cluster quality exceeding 0.5. The optimal number of clusters was identified as three, based on the size ratio of 1.29 between the largest and smallest clusters. k-means clustering achieved convergence in six iterations (

p < 0.001). Following that, k-means cluster analysis has been run for three clusters, and the model was achieved with an iteration value of 6 (supposed to be less than 10). Differences between groups have also been statistically proven (

p: 0.000). Then, the three Green Code classes were evaluated regarding the distribution of these SoP clusters, shown below in

Table 6.

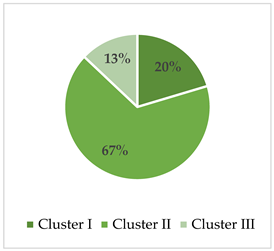

The first cluster was characterized by high satisfaction across all three SoP indicators and was predominantly composed of residents from single-family areas (56%), followed by the residential coded areas. The second cluster exhibited high place attachment, moderate place identity, and low place dependence, largely representing residential zones. The third cluster reflected low place attachment, high place identity, and moderate place dependence, and was mainly found in mixed-use areas. This pattern suggests that spatial recognition and symbolic value in mixed-use zones do not necessarily translate into emotional anchoring or functional reliance—highlighting a disjunction between visual legibility and day-to-day experience. The resulting performance scores, based on a maximum of 900 points, showed the strongest SoP satisfaction in single-family areas (768), followed by residential zones (747), and mixed-use areas (675).

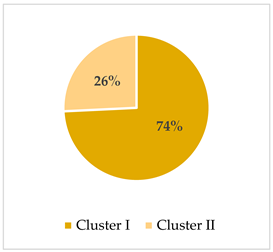

At the street scale, place dependence emerged as the strongest predictor (cluster quality > 0.4). k-means clustering stabilized after five iterations (

p < 0.001), resulting in three clusters (Ratio of sizes: 1.82). Following that, k-means cluster analysis has been run for three clusters and achieved the model with an iteration value of 5 (supposed to be less than 10). Differences between groups have also been statistically proven (

p: 0.000). Then, the three Green Code classes were evaluated regarding the distribution of these SoP clusters, as shown in

Table 7 below. The first cluster, representing the highest satisfaction across all three indicators, was largely dominated by residential areas. The second cluster reflected moderate satisfaction levels, while the third cluster showed low satisfaction across all indicators. Notably, 46% of mixed-use areas fell into this low-satisfaction cluster, indicating potential incompatibility between the built environment and user expectations at the street scale. This finding may reflect contextual issues, such as maintenance, traffic conditions, or perceived safety, which are not always addressed by form-based zoning but strongly influence street-level experience. It reinforces the need to pair physical design standards with ongoing urban management strategies. This makes the mixed-use areas have the lowest SoP performance. Single-family coded areas are probably the best in terms of SoP performance due to achieving 67% in Cluster II. The corresponding performance scores were highest for residential areas (600), followed by single-family (554), and mixed-use areas (524 out of 900).

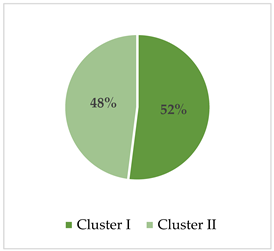

At the neighborhood scale, the clustering model also highlighted place dependence as the key predictor (cluster quality > 0.4). In this case, two clusters were identified, with a final size ratio of 1.30, and model convergence occurred after four iterations (

p < 0.001). Differences between groups have also been statistically proven (

p: 0.000). Then, the three Green Code classes were evaluated regarding the distribution of these SoP clusters, as shown in

Table 8 below. The first cluster, representing high satisfaction in place attachment and identity and moderate satisfaction in place dependence, mainly comprised respondents from residential areas. The second cluster included lower satisfaction across all indicators and was more evenly distributed. The final performance scores for this scale placed residential zones at the top (696), followed by mixed-use (648), and single-family areas (608).

The clustering results overall suggest that distinct affective responses are associated with different spatial types even within the same category. For instance, high symbolic identification in mixed-use zones coexists with lower functional satisfaction—indicating a possible disjunction between spatial recognition and everyday usability. This reinforces the need to distinguish between visual identity and lived functionality in future form-based code assessments.

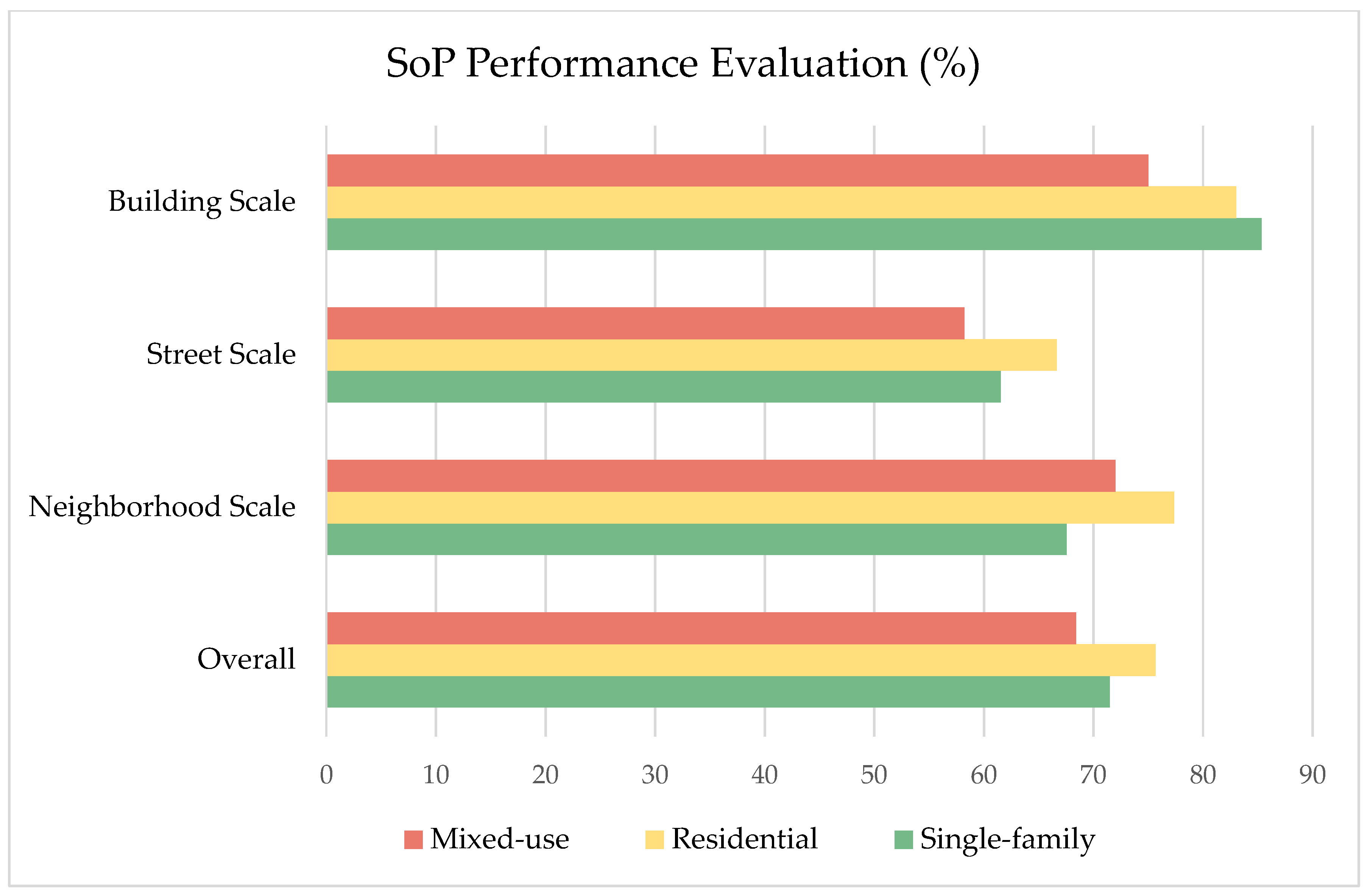

5.4. Overall SoP Performance Evaluation

The comparative SoP evaluation across spatial scales and Green Code categories as seen in

Figure 6 reveals meaningful patterns regarding how residents relate to their environment in Elmwood Village. The consistently higher satisfaction scores at the building scale suggest that intimate, immediate environments play a central role in shaping a strong sense of place. This may reflect the importance of architectural character, residential familiarity, and personal space in daily lived experience. Notably, residential and single-family coded areas outperformed other typologies, particularly at the street and neighborhood scales, indicating a stronger alignment between the physical environment and residents’ place-based expectations in these zones. Although mixed-use areas scored lower overall, they demonstrated comparatively higher ratings in place identity, pointing to a more symbolic or cognitive form of attachment. This may indicate that such areas, while perhaps lacking in functional or emotional resonance, still serve as meaningful landmarks or social hubs within the broader urban fabric.

6. Discussion

This research investigated how different urban form typologies—classified under the Green Code—contribute to residents’ lived experiences of place, namely sense of place (SoP) within the established residential context of Elmwood Village. Using a multi-scalar empirical framework that integrates spatial zoning classifications and perceptual indicators of place attachment, identity, and dependence, it built upon prior scholarship highlighting the role of physical form in shaping emotional and functional bonds to place [

7,

8,

9], and offered new empirical insights into the scale-sensitive performance of form-based codes (FBCs) in a U.S. urban context.

The findings reveal a differentiated pattern of SoP across spatial scales and zoning categories. The building scale emerged as the most positively perceived environment, particularly within residential and single-family coded areas. This suggests that immediate, private or semi-private spaces—such as homes and blocks—play a dominant role in shaping affective and functional bonds to place. This outcome resonates with earlier studies emphasizing the symbolic and emotional centrality of the domestic environment in sustaining place-based identity and attachment (e.g., [

9,

16,

53]). Architectural coherence, human-scale design, and visual familiarity in these zones may contribute to the continuity between form and experience that underpins strong SoP [

10,

11].

In contrast, mixed-use zones showed relatively lower satisfaction in place attachment and dependence, though they scored highest in place identity. This dichotomy suggests that although mixed-use environments may enhance recognition and legibility, they do not necessarily fulfill deeper emotional or functional place needs (e.g., [

9,

11]). This points to a potential mismatch between the intended goals of mixed-use design and the lived realities of residents. These findings challenge conventional assumptions within urban design that mixed-use automatically equates to livability or social satisfaction. Rather, they highlight the need to distinguish between the perceptual qualities of place identity and the more intimate, behaviorally grounded experiences associated with place attachment and dependence.

Another critical observation is the relatively weak SoP reported at the street scale. Although form-based codes emphasize the pedestrian realm and street design as key levers for placemaking [

2,

31], our findings suggest that this scale may be more vulnerable to contextual and managerial shortcomings. Several factors may explain this discrepancy. First, implementation gaps could be at play [

32]: although the Green Code establishes design intentions for street environments, the actual physical upgrades (e.g., sidewalk conditions, greenery, lighting, seating) may lag behind policy due to funding or coordination constraints. Second, street-level satisfaction is more vulnerable to transient elements like traffic, noise, cleanliness, and perceived safety [

14,

15]—factors often outside the scope of zoning regulations but central to daily experience. Third, streets are inherently shared and dynamic spaces, shaped by both design and social behavior. In contrast to private or semi-private spaces, like homes or blocks, the public nature of streets may reduce emotional attachment or create a sense of detachment, especially if upkeep or social cues are inconsistent. This reflects a gap between policy aspirations and operational implementation. While codes may regulate building frontages, setbacks, or sidewalk widths, the actual experience of the street is shaped by a complex mix of physical and social variables—many of which lie outside the reach of regulatory tools. These results support the argument that effective placemaking at the street level requires not only design control but also sustained urban management strategies that address the dynamic and shared nature of public space. The uneven distribution of SoP across different Green Code categories also raises questions about the one-size-fits-all application of form-based regulations. Although the code aims to standardize the relationship between built form and public realm, the results demonstrate that residents’ experience of place is highly contextual. For instance, while single-family areas performed well across all indicators, mixed-use areas generated more polarized responses. Lynch’s [

55] concept of urban ‘legibility’—emphasizing paths, edges, and nodes as key perceptual elements—aligns with our finding that street-scale design critically influences place identity. Similarly, Robert Venturi’s [

56] work on symbolic urban form contextualizes why mixed-use zones score high in identity but low in functional attachment. This underscores the importance of adaptive zoning strategies that are responsive to both spatial scale and user perception. The assumption that formal consistency leads to experiential consistency is not supported by the data.

The clustering analysis further deepens these insights by illustrating how different combinations of SoP indicators cluster around specific code typologies. For example, while place identity was highest in mixed-use areas, these zones failed to generate equally strong outcomes in place attachment and dependence. Conversely, more balanced SoP clusters were associated with single-family and residential zones. These findings underscore the importance of holistic design strategies—those that do not merely generate visual distinctiveness or spatial variety but also nurture day-to-day usability, emotional bonds, and community continuity. They further suggest that successful form-based planning must not rely on assumed benefits of typologies such as mixed-use development but rather should be rigorously evaluated in relation to residents’ situated experiences.

Taken together, these findings contribute to the broader discussion on how regulatory frameworks can be evaluated not just by their formal logic, but by their ability to sustain or enhance meaningful human–place relationships. While form-based codes provide a valuable tool for shaping urban form, their true success lies in how well they align with lived experience. This study demonstrates that such alignment is uneven and spatially dependent, reinforcing the need for grounded, empirically informed revisions to code practices. Urban planners and policymakers must consider the limits of design-based regulation and recognize that the experiential outcomes of place depend on a complex interplay between form, function, and daily life.

Methodologically, this research offers a transferable framework for evaluating SoP in form-based regulatory contexts. The integration of validated psychological indicators with spatial zoning data and cluster analysis enables a more fine-grained understanding of how urban regulations affect perceived place quality. The use of a multi-scalar approach allows for the identification of where design interventions succeed or fail. This framework may serve as a practical tool for municipalities aiming to assess the experiential performance of zoning policies.

Nonetheless, this study has limitations. While the six official Green Code zoning types offer valuable granularity, they were aggregated into three broader typologies (mixed-use, residential, and single-family) for the purposes of statistical validity and sample size balance. However, this simplification may obscure local morphological distinctions and reduce sensitivity to nuanced spatial variation—particularly between N-2R and N-3R residential types. This limitation is acknowledged, and future studies are recommended to adopt a finer-grained analytical lens where sample distribution allows. Furthermore, demographic variation among respondents was not isolated in the analysis, although factors such as age, tenure, or socio-economic status are likely to influence perceptions of place [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. While this study controls for spatial variables, demographic factors (e.g., length of residency, income) may moderate place attachment. Future work should incorporate these covariates to isolate zoning effects. Moreover, the emphasis on quantitative indicators—while valuable for generalizability—leaves out the richer narratives that qualitative methods could provide. Future research might enhance the current framework by incorporating interviews, ethnographic observation, or participatory mapping to uncover latent meanings and emotional nuances that surveys may overlook [

24]. A particularly promising direction would be to focus further on the N-2R residential areas, which represent over 70% of Elmwood Village and offer an ideal microcosm for refining the relationship between built form and perceived continuity. Exploring which specific spatial characteristics within this zone correlate with high SoP scores could guide future code amendments or preservation strategies.

These findings resonate with prior studies on New Urbanist environments that found symbolic place identity often higher in mixed-use areas but not always matched by emotional or functional attachment (e.g., [

9,

11]). Similarly, Quinn-Smith [

32] noted implementation gaps in street-level FBC performance. Unlike those studies, however, this research contributes a multi-scalar evaluation of lived experience within an established neighborhood, offering empirical insight into how typologies perform differently across spatial scales. These patterns also demonstrate the nuanced relationship between regulatory design and lived experience, which holds clear relevance for future code evaluations and revisions. However, while Buffalo’s Green Code represents a form-based approach, the findings should not be generalized to all FBCs.

7. Conclusions

Building on these findings, this study concludes that while Buffalo’s Green Code demonstrates notable capacity to foster sense of place (SoP), its impact is spatially uneven and typology-dependent. Residential and single-family zones, particularly at the building scale, consistently support stronger place attachment, identity, and dependence, reflecting a close alignment between physical form and lived experience. In contrast, mixed-use zones—though symbolically rich—underperform in emotional and functional dimensions, challenging conventional assumptions about the inherent social value of mixed-use planning. These results systematically fulfil the study’s objectives: perceptions of SoP were assessed across three core dimensions, compared across zoning typologies, analyzed at multiple spatial scales, and mapped to reveal emergent spatial patterns of satisfaction. In doing so, the study reveals not only the strengths and shortcomings of form-based codes but also the complex interplay between design intention and lived meaning.

Beyond its empirical findings, this study offers practical implications for urban zoning practice. The findings of this study offer several actionable insights for future form-based code revisions. First, the scale-dependent variation in sense of place (SoP) suggests that zoning regulations should be calibrated more precisely across spatial levels—providing differentiated design guidelines for buildings, streetscapes, and neighborhoods rather than a uniform regulatory approach. Second, the performance disparities across typologies highlight the need for typology-specific refinements. For instance, mixed-use zones—despite their high symbolic identity—exhibited lower levels of place attachment and dependence, indicating that future code revisions might prioritize enhancing functional amenities, managing transitions between uses, and reinforcing residential usability in these zones. Finally, the integration of perceptual data—such as residents’ emotional and functional satisfaction—into zoning performance evaluation offers a replicable model for planning agencies aiming to align regulatory intent with lived experience. These implications reinforce the potential of form-based codes not only as spatial tools but as adaptive frameworks responsive to human–place relationships.

This research contributes a replicable, multi-scalar evaluative framework that integrates spatial classification with perceptual metrics to assess how zoning codes align with place-based experience. Methodologically, the study demonstrates how lived experience can be empirically incorporated into planning evaluation, offering planners a diagnostic tool to calibrate form-based interventions. Importantly, it argues that while design codes may structure urban form, they cannot—on their own—guarantee meaningful or coherent place experiences. Codes must remain flexible, responsive, and informed by ongoing feedback from the communities they shape.

As cities increasingly turn to form-based planning in pursuit of livable, inclusive, and character-rich environments, this study highlights the need to bridge regulatory intention with perceptual reality. Elmwood Village offers both caution and promise: it illustrates the potential of well-aligned design to nurture belonging, but also the risks of assuming that formal coherence translates into experiential satisfaction. Place is not produced by code alone—it emerges through the evolving dialogue between people and the spaces they inhabit. While typological aggregation enabled a robust comparison, future studies should explore zoning diversity at a more granular level to capture overlooked local variation.

*

* *

* *

*