The Influence of Eco-Anxiety on Sustainable Consumption Choices: A Brief Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Climate Distress and Sustainable Behavioral Responses

2.2. From Environmental Behavior to Green Consumerism

3. Methods: Literature Search Strategy and Data Extraction

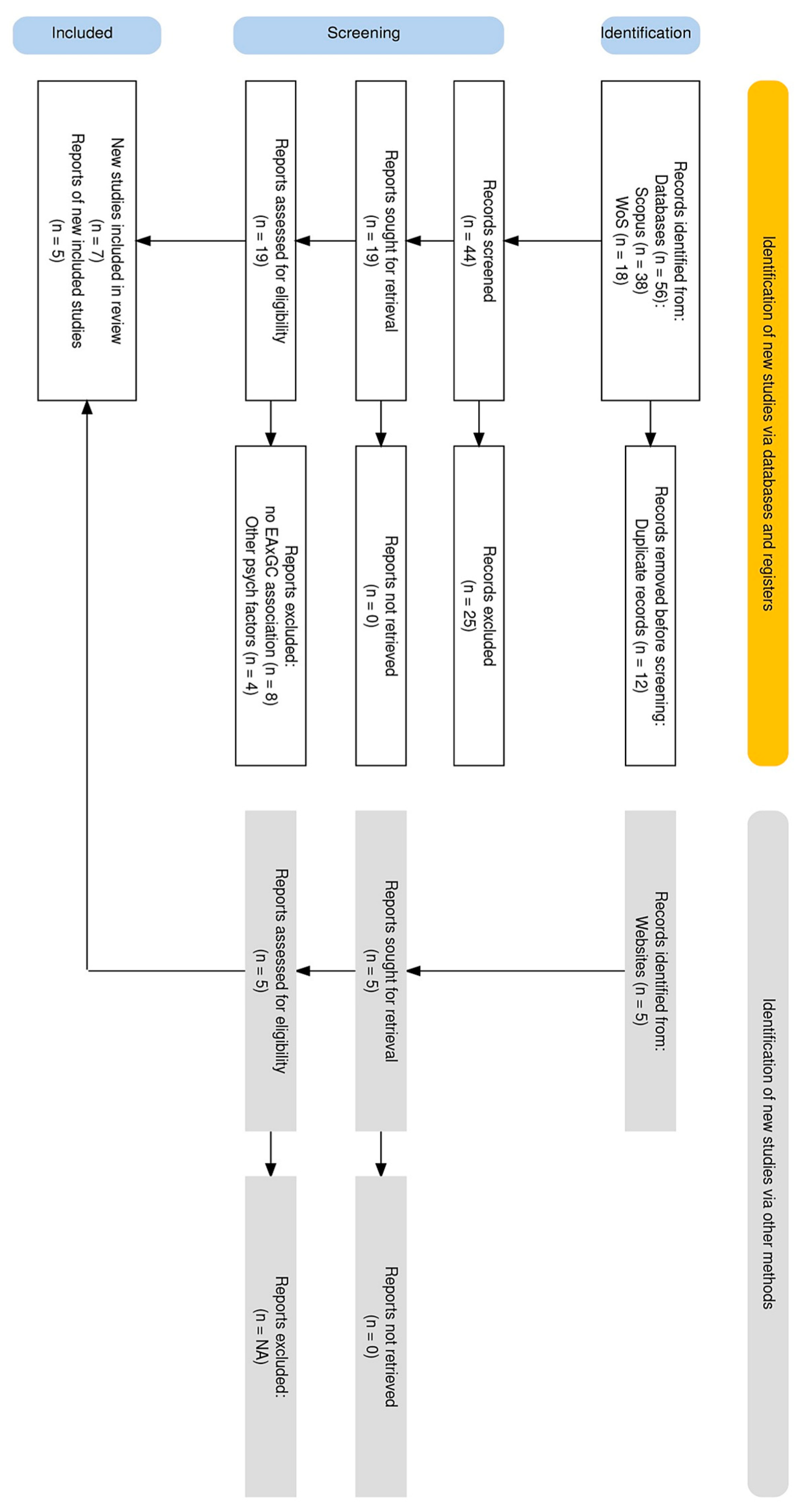

- Study identification includes literature search for all relevant studies using predefined strategies and databases. This step emphasizes comprehensive and unbiased retrieval of the literature, including peer-reviewed articles, gray literature, and agency reports, to avoid missing important data or introducing bias [73,74]. This step involves the establishment of inclusion and exclusion criteria derived from the SIDER framework (refer to Table 2 for detailed eligibility criteria), which in turn result in the development of specific keywords and search strings based on Boolean logic to be used in specific databases. In this review, we implemented the search strategy in Scopus and Web of Science databases using the exact search strings presented in Table 3. Following PRISMA 2020 guidelines, Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the search strategy.

- At this stage, the data from the included studies are synthesized either quantitatively (meta-analysis) or qualitatively (narrative synthesis) [75]. The current review is qualitative by design to align with the initial core objective of a brief narrative review that assesses the impact of eco-anxiety on sustainable consumption. Evidence synthesis follows the screening of all the studies. We used the Rayyan web tool for systematic review to import the .ris files from Scopus and WoS, detect duplicates, and procced with the initial screening process of abstracts, titles, and keywords of all records (n = 56; refer to Figure 1). The final screening procedure entailed full-text evaluation of the records that passed the initial evaluation. Based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of only 7 studies were eligible. Due to the limited number of resulting records, we further employed a supplementary search of gray literature on Google Scholar to search for additional reports (search was limited to 5 first pages of results). The latter procedure revealed 5 new studies that met the inclusion criteria (Table 3).

- Finally, the findings are interpreted in the context of the original research question. This step is about discussing the implications, limitations, and relevance of the results, and includes recommendations for practice, policy, or future research [76]. Accordingly, Table 4 presents an overview of the 12 eligible studies, including information about authors, publication year, databases, journal/source, country, research design, data analysis, sample, basic study measures, and main results concerning the eco-anxiety–sustainable consumption relationship. In Section 4 and Section 5 we critically discuss the review results and make policy and future research recommendations.

4. Main Findings on Climate Anxiety and Green Consumerism

4.1. Prevalence and Predictive Role of Eco-Anxiety

4.2. Emotional and Psychological Mediators

4.3. Cross-Cultural and Demographic Moderators

4.4. Real-World Consumer Behavior Outcomes

5. Interpretation and Policy Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. Assessing values, attitudes, and threats towards marine biodiversity in a Greek coastal port city and their interrelationships. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 167, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. A Multi-dimensional Measure of Environmental Behavior: Exploring the Predictive Power of Connectedness to Nature, Ecological Worldview and Environmental Concern. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 143, 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers-Jones, J.; Todd, J. Ecological anxiety and pro-environmental behaviour: The role of attention. J. Anxiety Disord. 2023, 98, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavani, J.-B.; Nicolas, L.; Bonetto, E. Eco-Anxiety motivates pro-environmental behaviors: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study. Motiv. Emot. 2023, 47, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Newman, D.B. Eco-anxiety in daily life: Relationships with well-being and pro-environmental behavior. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 4, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkarslan, K.K.; Kozak, E.D.; Yıldırım, J.C. Psychometric properties of the Hogg Eco-anxiety scale (HEAS-13) and the prediction of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 92, 102147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M.; Fiorenza, M.; Bellotti, M.; Severino, F.P.; Valdrighi, G.; Guazzini, A. Highly Sensitive People and Nature: Identity, Eco-Anxiety, and Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becht, A.; Spitzer, J.; Grapsas, S.; van de Wetering, J.; Poorthuis, A.; Smeekes, A.; Thomaes, S. Feeling anxious and being engaged in a warming world: Climate anxiety and adolescents’ pro-environmental behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2024, 65, 1270–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’BRien, L.V.; Watsford, C.R.; Walker, I. Clarifying the nature of the association between eco-anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, Z.; Kelly, M.; Brown, S. The Relationship between Climate Anxiety and Pro-Environment Behaviours. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühner, C.; Rudolph, C.W.; Zacher, H. Reciprocal Relations Between Climate Change Anxiety and Pro-Environmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2024, 56, 408–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Broek, K.L.v.D.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S.D.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J.A.; et al. Climate anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental action: Correlates of negative emotional responses to climate change in 32 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to green consumption: A systematic review. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 23, pp. 4826–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.P. Consumers’ purchase behaviour and green marketing: A synthesis, review and agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Haley, E. Green consumer segmentation: Consumer motivations for purchasing pro-environmental products. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 1477–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W.; Hung, C.-Z. Sustainable consumption: Research on examining the influence of the psychological process of consumer green purchase intention by using a theoretical model of consumer affective events. In Environment, Development and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduku, D. How environmental concerns influence consumers’ anticipated emotions towards sustainable consumption: The moderating role of regulatory focus. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabasakal-Cetin, A. Association between eco-anxiety, sustainable eating and consumption behaviors and the EAT-Lancet diet score among university students. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 111, 104972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, S. HEXACO traits, emotions, and social media in shaping climate action and sustainable consumption: The mediating role of climate change worry. Psychol. Int. 2024, 6, 937–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.M.; Nguyen, N.T.; Ngo, T.L.; Le, T.T. How climate change anxiety enhances sustainable trust and consumption behavior: Evidence from Vietnam and Italy. In Business Strategy & Development; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Matsiori, S. Development and validation of a scale for measuring Multiple Motives toward Environmental Protection (MEPS). Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 58, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, P.; Betrò, S.; Janiri, L. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health: A Systematic Descriptive Review. Front. Psychiatry. 2020, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S. Climate Change and Mental Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2021, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurth, C.; Pihkala, P. Eco-anxiety: What it is and why it matters. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 981814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedzwiedz, C.; Katikireddi, S.V. Determinants of eco-anxiety: Cross-national study of 52,219 participants from 25 European countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, ckad160.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.M.; Krygsman, K.; Speiser, M. Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance; American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica: Washington, WA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The psychological impacts of global climate change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, G. Psychoterratic conditions in a scientific and technological world. In Ecopsychology: Science, Totems, and the Technological Species; Kahn, P.H., Jr., Hasbach, P.H., Eds.; Boston Review: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 241–264. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluda-Verdú, I.; Senent-Valero, M.; Casas-Escolano, M.; Matijasevich, A.; Pastor-Valero, M. Fear for the future: Eco-anxiety and health implications, a systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, H.; Olson, J.; Paul, P. Eco-anxiety in youth: An integrative literature review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 633–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Lutz, P.K.; Howell, A.J. Eco-Anxiety: A Cascade of Fundamental Existential Anxieties. J. Constr. Psychol. 2022, 36, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, K.; Durkin, J.; Bhullar, N. Eco-anxiety: How thinking about climate change-related environmental decline is affecting our mental health. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 1233–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, C. We need to (find a way to) talk about … Eco-anxiety. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2020, 34, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’BRien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, M.-L.; Weiss, K.; Aroua, A.; Betry, C.; Rivière, M.; Navarro, O. The influence of environmental crisis perception and trait anxiety on the level of eco-worry and climate anxiety. J. Anxiety Disord. 2024, 101, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innocenti, M.; Santarelli, G.; Faggi, V.; Castellini, G.; Manelli, I.; Magrini, G.; Galassi, F.; Ricca, V. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Marks, E.; Dobromir, A.I. On the nature of eco-anxiety: How constructive or unconstructive is habitual worry about global warming? J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Poortinga, W.; Williams, M. Climate Anxiety in the United Kingdom: Associations with Environmentally Relevant Behavioural Intentions, and the Moderating Role of Efficacy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 105, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, L.; Latorre, F.; Vecina, M.L.; Díaz-Silveira, C. What Drives Pro-Environmental Behavior? Investigating the Role of Eco-Worry and Eco-Anxiety in Young Adults. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullenkord, M.C.; Johansson, M.; Loy, L.S.; Menzel, C.; Reese, G. Go out or stress out? Exploring nature connectedness and cumulative stressors as resilience and vulnerability factors in different manifestations of climate anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Santarelli, G.; Lombardi, G.S.; Ciabini, L.; Zjalic, D.; Di Russo, M.; Cadeddu, C. How Can Climate Change Anxiety Induce Both Pro-Environmental Behaviours and Eco-Paralysis? The Mediating Role of General Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, L.; Yu, G. Media coverage of climate change, eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior: Experimental evidence and the resilience paradox. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 91, 102130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, A.; Mouguiama-Daouda, C.; McNally, R.J. A network approach to climate change anxiety and its key relaed features. J. Anxiety Disord. 2023, 93, 102625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangervo, J.; Jylhä, K.M.; Pihkala, P. Climate anxiety: Conceptual considerations, and connections with climate hope and action. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 76, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, Â.; Lopes, D.; Pereira, L. Pro-Environmental Behavior and Climate Change Anxiety, Perception, Hope, and Despair According to Political Orientation. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.; Wu, Q.; Bi, C.; Deng, Y.; Hu, Q. The relationship between climate change anxiety and pro-environmental behavior in adolescents: The mediating role of future self-continuity and the moderating role of green self-efficacy. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, S.K.; Harichandan, S. Green marketing innovation and sustainable consumption: A bibliometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haba, H.F.; Bredillet, C.; Dastane, O. Green consumer research: Trends and way forward based on bibliometric analysis. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 8, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Maimaituerxun, M. Research Progress of Green Marketing in Sustainable Consumption based on CiteSpace Analysis. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why Do Consumers Make Green Purchase Decisions? Insights from a Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megha, M. Determinants of green consumption: A systematic literature review using the TCCM approach. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1428764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotisarn, N.; Phuthong, T. Green production processes and consumer behaviour: A theory-context-characteristics-methodology framework-based systematic review and future research agenda. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2025, 18, 2480100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, A.; Catană, Ș.-A.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Cioca, L.-I.; Ioanid, A. Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior toward Green Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, M.D.; Attri, R.; Salam, M.A.; Yaqub, M.Z. Bright and dark sides of green consumerism: An in-depth qualitative investigation in retailing context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M.; Manolova, T.S. Sustainable development: Predictors of green consumerism in Slovenia. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1695–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ka, L.S.; Nguyen, T.K. What Leads Households to Green Consumption Behavior: Case of a Developing Country. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nga, L.P.; Tam, P.T. Managerial Recommendations for Enhancing Green Consumption Behavior and Sustainable Consumption. Emerg. Sci. J. 2024, 8, 2245–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustam, A.; Wang, Y.; Zameer, H. Environmental awareness, firm sustainability exposure and green consumption behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.M.; Gomes, S.; Trancoso, T. Navigating the green maze: Insights for businesses on consumer decision-making and the mediating role of their environmental concerns. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2024, 15, 861–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.F.; Yuan, J.; Shahzad, K.; Huang, Y. Drivers of green consumption: Ethical ideologies and corporate social responsibility in sustainability awareness. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 3196–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W. Consumer behaviour and environmental sustainability. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, G.; Secer, A.; Ghazalian, P.L. What Factors Influence Consumers to Buy Green Products? An Analysis through the Motivation–Opportunity–Ability Framework and Consumer Awareness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecer, K.; Çetiïn, M.; Ülker, S.V. The Climate Crisis and Consumer Behavior: The Relationship between Climate Change Anxiety and Sustainable Consumption. Kahramanmaraş Sutcu Imam Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 20, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.; Booth, A.; Varley-Campbell, J.; Britten, N.; Garside, R. Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: A literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed-Shaffril, H.A.; Samsuddin, S.F.; Abu Samah, A. The ABC of systematic literature review: The basic methodological guidance for beginners. Qual. Quant. 2021, 55, 1319–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Khatri, P.; Duggal, H.K. Frameworks for developing impactful systematic literature reviews and theory building: What, Why and How? J. Decis. Syst. 2023, 33, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausman, P.R. Preparing effective systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J. Wildl. Manag. 2024, 88, e22547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P.A. Methodological Guidance Paper: The Art and Science of Quality Systematic Reviews. Rev. Educ. Res. 2020, 90, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakó, F.; Szeberényi, A. Young Adults’ Feelings and Knowledge of Climate Anxiety. J. Sustain. Res. 2025, 7, e250025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, I.; Dal, N. The Effects of Death Anxiety, Health Anxiety and Environmental Anxiety on the Intention to Purchase Eco-Friendly Product and Consumption Behavior. Istanb. Bus. Res. 2024, 53, 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, A.M. Climate Change and Consumer Behaviour—The Impact of Eco-Anxiety on the Consumption Habits of Finns Below 30 Years of Age. Master’s Thesis, Jyväskylä University, School of Business and Economics, Jyväskylä, Finland, 2022. Available online: https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstreams/654c1717-6c3e-4df9-a739-4cb67a18ac62/download (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Wesselow, K. Don’t Worry, Be Hungry? Assessing the Relationship Between Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Eco-Anxiety Using Climate-Friendly Food Systems Labels. Student Reports (Undergraduate), UBC Social Ecological Economic Development Studies (SEEDS), Vancouver/Okanagan, BC, Canada, 2022. Available online: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/undergraduateresearch/18861/items/1.0421612 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Balaskas, S.; Komis, K. Predicting Sustainable Consumption Behavior from HEXACO Traits and Climate Worry: A Bayesian Modelling Approach. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Paço, A.; Rocha, R.G.; Palazzo, M.; Siano, A. Examining a theoretical model of eco-anxiety on consumers’ intentions towards green products. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1868–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Zhou, Y.; Geng, L. Low-carbon consumption in extreme heat in eastern China: Climate change anxiety as a facilitator or inhibitor? J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 483, 144271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Bristow, J. At the intersection of mind and climate change: Integrating inner dimensions of climate change into policymaking and practice. Clim. Change 2022, 173, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhong, W.; Naz, S. Can Environmental Knowledge and Risk Perception Make a Difference? The Role of Environmental Concern and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Fostering Sustainable Consumption Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosh, S.M.; Ryan, R.; Fallander, K.; Robinson, K.; Tognela, J.; Tully, P.J.; Lykins, A.D. The relationship between climate change and mental health: A systematic review of the association between eco-anxiety, psychological distress, and symptoms of major affective disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (S) Ample | Adult and Young Individuals/General Population Samples |

|---|---|

| (P) henomenon of (I) nterest |

|

| (D) esign |

|

| (E) valuation |

|

| (R) esearch Type |

|

| No | Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Type of studies |

|

|

| 2 | Type of population |

|

|

| 3 | Type of evaluations/constructs of interest |

|

|

| 4 | Type of outcome |

|

|

| 5 | Limits |

|

|

| Database | Keywords/Search Strings (Boolean Logic) | Records |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“eco-anxiety” OR “climate anxiety” OR “ecological anxiety”OR “climate distress” OR “eco distress”) AND (“sustainable consumption” OR “green consumption” OR “green consumerism” OR “sustainable consumer behavior” OR “environmentally responsible consumption”)) | 38 |

| Web of Science | TS = (“eco-anxiety” OR “climate anxiety” OR “environmental anxiety” OR “ecological distress” OR “eco-worry” OR “eco-emotions” OR “ecological grief” OR “ecological worry” OR “climate emotion”) AND TS = (“sustainable consumption” OR “green consumerism” OR “green consumption” OR “green purchase behavior” OR “consumer behavior” OR “consumption behavior” OR “buying behavior” OR “purchase intention” OR “sustainable purchasing” OR “green buying”) and Preprint Citation Index (Exclude–Database) | 18 |

| Google Scholar (Gray Literature) | Key words and Query String: ALL(Eco-anxiety OR (climate AND anxiety)) AND (Consumption OR consumerism) AND (sustainable OR green) | 5 |

| Authors and Publication Year | Database | Source Title | Country | Research Design | Data Analysis | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| López-García et al. (2025) [43] | Scopus/WoS | Sustainability | Spain | Cross-sectional | CFA SEM | n = 308 young adults aged 18–30 |

| Bakó & Szeberényi (2025) [77] | Scopus | Journal of Sustainability Research | Hungary | Cross-sectional | Naive Bayes, logistic regression, and random forests, | N = 696 university students |

| Korkmaz, Ilknur & Nil Esra (2024) [78] | WoS | Istanbul business research | Türkiye | Cross-sectional | PLS-SEM | n = 465 |

| Kohl (2022) ** [79] | Google Scholar | Jyväskylä University Library School of Business and Economics | Finland | Cross-sectional | χ2 tests | Total n = 2070 (343 under 30 years target group) |

| Wesselow (2022) * [80] | Google Scholar | University of British Columbia, Social Ecological Economic Development Studies (SEEDS) Sustainability Program, Student Research Report | Multi-cultural participation (Qualtrics survey/Study 1) Great Britain (Study 2) | Cross-sectional (Study 1) Quasi-experimental study (Study 2) | Pearson’s correlation Linear Regression t-tests χ2 tests | Study 1 n = 251 Study 2 n = 15,379 (sales data) |

| Ecer et al. (2023) * [68] | Google Scholar | Kahramanmaraş Sutcu Imam University Journal of Social Sciences | Türkiye | Cross-sectional | SEM | n = 450 |

| Kabasakal-Cetin (2023) [19] | Scopus/WoS | Food Quality and Preference | Türkiye | Cross-sectional | Pearson correlational analysis Multiple regression analysis | n = 605 |

| Balaskas (2024) * [20] | Google Scholar | Psychology International | Greece | Cross-sectional | Hierarchical regression analysis | n = 604 |

| Balaskas & Komis (2025) [81] | Google Scholar | Psychology International | Greece | Cross-sectional | Bayesian Pearson correlation Bayesian regression approach | n = 604 |

| Sharma et al. (2024) [82] | Scopus/WoS | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | India Italy | Cross-sectional | PLS-SEM | Total n = 557 (316 from India; 241 from Italy). |

| Wan et al. (2024) [83] | WoS | Journal of Cleaner Production | China | Experimental design | Mediation analysis (Process) t-tests | n = 198 (Study 1) n = 203 (Study 2) |

| Nguyen et al. (2025) [21] | WoS | Business Strategy & Development | Vietnam Italy | Mixed-methods design | Semi-structured in-depth interviews, participant observation, and expert interviews PLS-SEM | n = 681 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkargkavouzi, A.; Halkos, G.; Halkou, P. The Influence of Eco-Anxiety on Sustainable Consumption Choices: A Brief Narrative Review. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9070286

Gkargkavouzi A, Halkos G, Halkou P. The Influence of Eco-Anxiety on Sustainable Consumption Choices: A Brief Narrative Review. Urban Science. 2025; 9(7):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9070286

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkargkavouzi, Anastasia, George Halkos, and Panagiota Halkou. 2025. "The Influence of Eco-Anxiety on Sustainable Consumption Choices: A Brief Narrative Review" Urban Science 9, no. 7: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9070286

APA StyleGkargkavouzi, A., Halkos, G., & Halkou, P. (2025). The Influence of Eco-Anxiety on Sustainable Consumption Choices: A Brief Narrative Review. Urban Science, 9(7), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9070286