1. Introduction

It has been three decades since the attacks on the Tokyo Subway by terrorists, in which they released Sarin in the morning peak hour on 20 March 1995. The release of this toxic gaseous substance, which led to the death of 11 commuters and more than 5000 persons requiring emergency medical evaluation, brought to the forefront one of the biggest challenges facing authorities, namely the impact of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) incidents in such dense, urban locations. The issue with such incidents is the significant challenge these pose to casualties requiring, as they do, swift, coordinated responses to safeguard the public’s health [

1,

2].

Urban areas are at particular risk from a CBRN attack due to their high population densities, economic and political significance, transportation hubs and the extensive media coverage which will be generated due to these factors. Cities are, therefore, an attractive target for causing high levels of casualties, causing widespread disruption, and amplifying the psychological impact of any attack. City and urban planners must therefore consider how to effectively manage a response to such threats, including the use of mass decontamination, should they materialise.

This paper examines the literature relating to factors that affect casualty behaviours during disasters and emergencies, specifically those involving hazardous materials (Hazmat)/CBRN materials and mass decontamination. It further considers the literature on how emergency responders can influence such behaviours to improve co-operation with those affected. In particular, this review aims to highlight previous scholarship in human factors during disasters and emergencies, specifically those relating to mass decontamination. This will be carried out to prevent duplication, as well as to support the identification of gaps in the research or areas of discrepancy or conflict which require resolution and further research.

With limited literature on human behaviour relating to decontamination incidents, much can be learned from other disaster events which have been extensively studied. Hence, this paper examines the literature in relation to factors that affect public behaviour, including the following: risk perception, fear and anxiety, communication from responders and trust in responders. Most of the publicly available literature in this domain has investigated the role of crowds in influencing these relationships [

3,

4,

5], and this review supplements this by seeking to understand the factors that affect human behaviour at an individual level during disasters and emergencies in general, and with regards to decontamination in particular.

There is increasing recognition that the psychological effects of a Hazmat/CBRN incident on the public will affect their behaviours and, consequently, how they engage with emergency responders, influencing the efficacy of any emergency operations [

6,

7,

8], with the authors of [

9] stating that “the success of government interventions before, during and after a crisis…” relies “on the cooperation of the public” (p. 66).

There is some suggestion in the literature that incidents involving the need for decontamination, likely because of a Hazmat or CBRN event, have the potential for disorderly [

10,

11] or aggressive behaviours [

12], and that these types of non-co-operative behaviour would present a significant challenge for responding emergency services when trying to undertake decontamination operations. Whilst [

13] identified that fear, anxiety and confusion would be likely responses of the public to a Hazmat/CBRN release, ref. [

14] identified how such fear and anxiety during such incidents is likely to be increased if operations are managed ineffectively by emergency services. However, planning and preparations for mass decontamination incidents has primarily revolved around the technical elements of operations, and although this failing has begun to be rectified with the introduction of behavioural science inputs into both guidance and mass decontamination instructor training, there remains only a limited focus on human behavioural aspects [

14,

15]. This can be seen in the aftermath of the Tokyo Sarin attack, where analysis of the incident response focused primarily on the technical effectiveness of response capabilities, as detailed by [

16,

17,

18].

When human behaviour has been considered, it has often led to contradictory planning assumptions. Either it is assumed that members of the public requiring decontamination will be anxious and afraid and consequently simply accept and follow emergency service instructions, or, more commonly, it is assumed that those involved in an incident requiring decontamination will become irritational and even disorderly and will require strong control by emergency services if they are to be decontaminated [

18].

The belief in the need for strong control of casualties is based upon misconceptions of the likelihood of public disorder and myths surrounding mass panic, with many authorities assuming that “large gatherings have a tendency to act illogically and instinctively in the event of an emergency” (p. 220) [

19]. However, the literature on this topic has, for some time, shown such occurrences as being unlikely, with helpful and cooperative behaviours being more likely [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. As recognised by [

9], “when faced with disasters and emergencies, people become co-operative and panic is rare” (p. 72).

Even so, planning for emergencies will often “fail to incorporate human behaviour and are based on contradictory expectations” (p. 72) [

9]. Such misconceptions concerning human behaviour have led to strategies relating to human behaviour that focus on controlling those members of the public requiring decontamination in order to guard against disorderly behaviours [

26,

27]. Ref. [

28] also points out that part of these control measures includes withholding information from members of the public and that such a lack of information coupled with controlling strategies can, in fact, create public disorder and reduce casualties’ co-operation with any decontamination process. Furthermore, ref. [

28] suggests that a major reason for this is the perception, held by the public, that the actions carried out by emergency responders are illegitimate.

Beyond the risk of disorder and reduced public co-operation, limiting the information provided to the public is also likely to inhibit the ability of members of the public to participate willingly in the decontamination process. They will require instruction and advice so that they are capable of helping themselves and others [

29].

There is a need, therefore, to explore co-operation and how emergency responders can seek to positively influence and support members of the public to achieve an effective response to any Hazmat/CBRN incident requiring mass decontamination. This is of primary importance, as without such an understanding, inappropriate approaches may be utilised, inhibiting the potential for an effective response.

It is also worth noting that whilst this paper is focused upon the human behavioural elements of a mass decontamination response, emerging work in the science and engineering disciplines offers new opportunities to simulate and model casualty behaviour during Hazmat/CBRN events. Computational modelling, such as agent-based simulations and digital twin frameworks, provides tools to better understand crowd dynamics and response optimisation in mass decontamination.

2. Methodology of This Narrative Review

This literature review uses a narrative approach examining the literature associated with mass decontamination and Hazmat/CBRN events specifically and disasters and emergencies more generally. A narrative approach allows for a comprehensive, critical and objective analysis of the current knowledge on a topic and, as such, enables a wider-ranging consideration across numerous fields to inform understanding in a manner which a systematic review would not allow [

30].

Given the necessity to expand beyond the existing literature, particularly by acknowledging the dominance of Carter’s contributions in the UK CBRN/mass decontamination field, a narrative review approach was deemed appropriate. Unlike traditional systematic reviews, which typically focus on synthesising existing evidence, a narrative review allows for a more exploratory and comprehensive examination of diverse sources, enabling the discovery of new ideas and perspectives. In particular, this narrative review was undertaken with the specific aim of exploring and synthesising a wide range of studies pertaining to the intersection of psychology, human behaviour, and emergency management. This review will focus on risk perceptions and communication in disaster situations, as well as CBRN incidents and mass decontamination procedures.

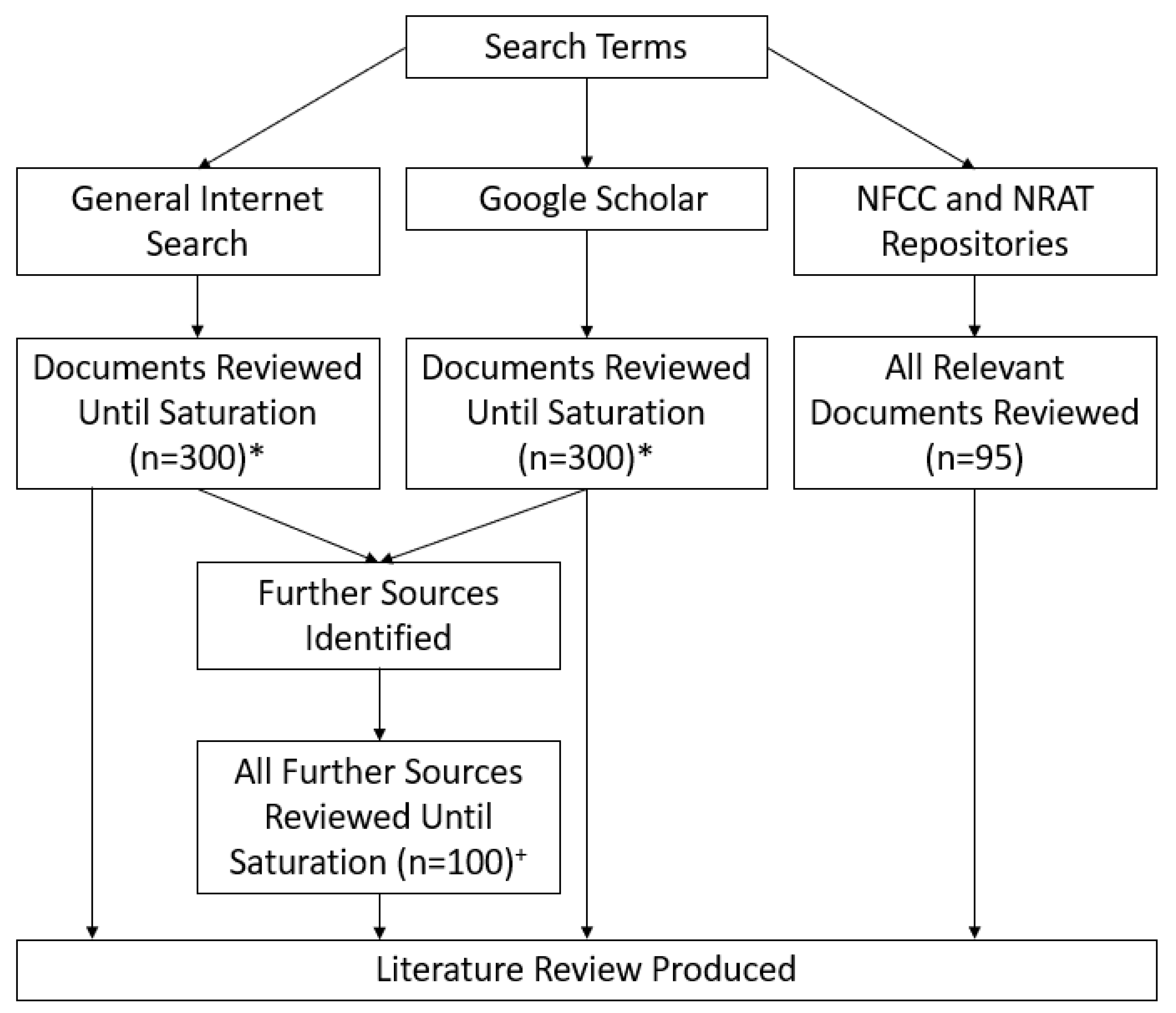

To accomplish this, a search was undertaken using Google Scholar, as was a more general internet search and a review of NFCC (National Fire Chiefs Council) and National Resilience documentation repositories. All documents relating to mass decontamination in the NFCC and National Resilience depositories was reviewed whilst the general internet search and Google Scholar search were conducted to review material until saturation, when there were consistently no new or relevant materials.

Google Scholar was chosen as the primary database for conducting a search of the literature due to the numerous advantages which it holds over other platforms. Google Scholar covers a very wide range of scholarly studies; alongside academic articles, it also includes access to theses, books and conference papers. The nature of this topic is explored in greater depth by emergency practitioners rather than academics and as such, access to conference papers and books in particular helped to ensure crucial studies on the topic were not overlooked by solely focusing on academic work.

Given the sensitive nature of this topic, there is a high likelihood that pertinent documents have not been shared publicly; it was for this reason that reviews of the National Fire Chief Council and National Resilience document repositories were undertaken. The search terms used across these platforms were “Risk Perceptions CBRN”, “Risk Perceptions Mass Decontamination”, Risk Communication CBRN”, Risk Communication Mass Decontamination”, CBRN Communications”, “CBRN Psychology”, CBRN Human Behaviour”, Mass Decontamination Communications”, “Mass Decontamination Psychology”, and “Mass Decontamination Human Behaviour”.

The initial literature identified in the review was then used to inform our search for more studies warranting review. The process for choosing the literature is set out in

Figure 1 below.

A narrative literature review is a type of review that provides a comprehensive summary and analysis of the current knowledge and research on a particular topic or research question [

31]. Unlike systematic reviews, which follow a specific set of guidelines and protocols to identify, select, and evaluate relevant studies, narrative reviews rely on the expertise and judgement of the author to identify and synthesise the relevant literature [

31]. Another feature of this approach is that it also allows for reflexivity to occur in the literature review process, i.e., a process of reflection based upon the researcher’s own background to influence the research process [

32].

A distinction needs to be made between reflection and reflexivity. Reflection seeks to provide insight by looking at an action or event and critically examining what happened, what was learned, and how it could be improved [

32]. A narrative approach allows reflexivity to occur in the literature review process, whereby there is a process of reflection upon the researcher’s own background to influence the research process [

32]. In contrast to reflection, reflexivity is a more active process involving ongoing self-awareness and a critical examination of the researcher’s positionality and assumptions. Furthermore, reflexivity acknowledges that the researcher is embedded in a context and that this will shape the perspectives, biases, and assumptions of the research [

32].

Throughout the literature review, the narrative process, coupled with an engagement with reflexivity, allowed for the researcher’s own background and experiences in the field to shape the review whilst acknowledging their positionality and how it influenced the review. To reiterate, this enabled the researcher to synthesise a much broader range of the literature than would have been achieved in a systematic review.

3. Results

The evidence from this narrative literature review indicates that individual and group responses are critically influenced by perceptions of risk, shaped through both cognitive and affective processes.

Trust in the legitimacy and competence of emergency responders emerges as a fundamental determinant of cooperative behaviour, mediating the public’s willingness to engage with protective actions. Effective risk communication—transparent, culturally sensitive, and practically oriented communication—plays a pivotal role in fostering this trust and guiding decision making under conditions of uncertainty.

This review further challenges outdated assumptions regarding mass panic, demonstrating that public behaviours during emergencies are more frequently rational and socially structured than chaotic. Crowd dynamics, influenced by social identity processes, can either facilitate or hinder the efficacy of decontamination operations depending on the strategies employed by responders. The findings also underscore the necessity of securing informed public agreement, addressing anxiety, and supporting vulnerable groups to enable successful decontamination outcomes.

Finally, advancements in computational modelling offer valuable tools to simulate and optimise these complex behavioural interactions, contributing to more evidence-based and adaptive emergency response planning. Collectively, these insights underscore the imperative to integrate behavioural and social considerations into the design and implementation of mass decontamination strategies.

3.1. Risk Perceptions

The authors of [

28] identify how casualties will respond to both a perceived threat, such as being contaminated, as well as to the [

28] way the threat is managed, and also acknowledge that this perception of risk being faced by casualties will influence how they behave during the decontamination process, therefore directly affecting the operations of emergency responders.

This is termed risk perception, and it is the subjective judgements of the perceived characteristics, likelihood and severity of a risk being faced [

33,

34,

35]. How risks are perceived is dependent upon a wide range of factors, including the traits of the individuals involved, such as personality traits, previous experience, and age, and aspects of the situation, such as the framing of risk information and the availability of alternative information sources, as well as how the risks are processed by individuals, such as through affective or cognitive processing [

34,

36]. When people are faced with a hazard, their risk perceptions of that hazard will affect how they react to it. It is crucial that emergency responders consider how members of the public requiring decontamination view the risks to their life and health [

7].

Any strategy put in place by emergency responders to manage a Hazmat/CBRN incident must consider the public’s perceptions of their risk, or else there is significant potential for a non-cooperative or even hostile response and there is certainly a likelihood that trust in emergency responders will be eroded [

37].

Feelings such as anxiety and fear resulting from the uncertainty, unfamiliarity and lack of control which a Hazmat/CBRN incident requiring mass decontamination will create will not be equally experienced the same way in all contexts as further factors such as past experiences and varying sociocultural factors will create differences between how social groups, cultures and nationalities perceive risks. A comparative study undertaken by [

38] compared the differences between people from Germany and the UK in their levels of fatalistic response to the use of a radiological explosive device more commonly referred to as a dirty bomb. The research showed fatalism to be stronger in Germany and related this to the dread risk widely felt in relation to nuclear risks due to the country’s association with the Chernobyl disaster.

There is a considerable body of literature that has been published on how the general public perceives risk [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45], but of particular interest to this paper are the mental processes which influence risk perceptions and how these can be influenced by emergency responders. Two factors stand out most prominently from the literature on risk perceptions: affect and trust [

46,

47]. Affect refers to the general positive or negative feelings which are felt toward a particular event, situation, or person [

48,

49], whilst trust is defined as the willingness to make oneself vulnerable to another because of expected beneficial outcomes [

50].

3.2. Risk Perception and Affect

Hazmat/CBRN releases are associated with strong emotional responses by any members of the public affected by them [

36]. These emotional responses are termed ‘Affect’. Affect has been used to explain how risks are perceived [

48,

51] by acting to provide a positive or negative evaluation of a stimulus. Ref. [

52] proposed the idea of affective primacy, suggesting that an affective evaluation of risk will occur before a cognitive evaluation of a stimulus does. The affective evaluation is based on approach avoidance, which involves asking if a situation is safe or hazardous and if it requires actions to be avoided. It is a very fast and instinctive process which is in constant use to help people keep themselves safe regardless of any hazard present [

52].

Alongside this approach, the psychometric paradigm looked to understand drivers of risk perceptions and also noted the role of affect [

40,

53,

54,

55]. These studies identified the role of familiarly, certainty and control and how these factors could produce ‘dread’ risks, which are far less readily accepted by individuals as they are perceived as risks which are uncontrollable and of very high severity. These findings have also been supported by [

36]. Ref. [

56] suggest that such dread risks will be affectively driven by fear and instinctive perceptions.

The use of affect to judge risk is also explained through the affect heuristic [

48,

57]. The affect heuristic states that people will hold positive and negative feelings towards a hazard built upon knowledge or some form of experience or exposure to that hazard [

45]. Their affective impression, built upon these positive and negative feelings, will determine how an individual perceives the risk of that hazard [

48,

57].

In relation to decontamination, this may mean that, should a member of the public require decontamination due to exposure to a radioactive material, they may view the risk as particularly high if their experience of this scenario is based on, say, the HBO TV drama Chernobyl (2019), which presents a particularly stark view of the outcomes of radiological exposure. This experience would leave them with a very negative view of this risk, even if the current exposure is significantly lower-risk than the radiological risk following the Chernobyl disaster itself [

58].

These theories have developed into a dual-process approach which seeks to explain how people perceive risk [

51,

56,

59,

60]. Dual-process theories delineate between immediate and deliberate processes which influence risk perceptions. The immediate processes are a quick appraisal requiring minimal effort and relying on simplistic rules to develop a perception of the risk being faced, whereas deliberate processes are considered cognitive processes which require more time and effort than the immediate processes. Ref. [

61] proposed that, should an individual have sufficient time and cognitive capacity, then it will be the deliberate process which will influence risk perception, and if not, the immediate process will be utilised instead. Both of these processes can be used simultaneously [

51,

58] and, as identified by [

51], the two processes may influence each other and their outcomes.

Overall, affective feelings have been shown to have a significant influence on risk perceptions; however, cognitive processes will influence and be influenced by the affective process and can overrule the affective process in the development of risk perception when people have enough time, cognitive capacity and motivation [

51].

3.3. The Role of Trust in Risk Perceptions

Ref. [

62] defines trust as being a psychological state involving an individual accepting vulnerability with the expectation of a positive behaviour or positive intention from others in response. Trust appears as a critical element in how risk is managed [

45,

63,

64,

65] and has been used to explain how casualties perceive responders, especially in unfamiliar situations [

66,

67,

68].

Furthermore, trust has been shown to have wide-ranging impacts in social interactions within risky scenarios. It has been shown to simplify how risk information is processed and has been described as a lubricant of social interactions [

69,

70]. Trust has been shown to reduce social uncertainty and complexity [

68] and influence risk perceptions, with increased levels of trust leading to an increase in the likelihood of the adoption of information or adherence to instructions [

71,

72]. Further, it has also been shown to directly impact the likelihood of cooperation occurring [

73]. Finally, trust has been shown to be a critical component of how public risk perception is formed and of how effective risk communication is [

9,

74,

75]. A high-profile example of this is found following the anthrax attacks in the US in 2001: [

72] identified that information was held as trustworthy and therefore was more likely to be acted upon if it came from a trusted spokesperson.

The trustworthiness of responders will therefore be crucial in reducing the uncertainty and unfamiliarity of members of the public involved in a Hazmat/CBRN incident, and the actions of emergency responders will shape the levels of co-operative and compliant behaviours experienced [

36]. Likewise, ref. [

36] states how pre-existing low trust or a loss of trust during an incident will have an adverse effect on the likely levels of co-operative behaviours impacting the emergency response process. Trust is therefore likely to influence casualty behaviours in relation to co-operation with recommended protective behaviours [

76,

77] and compliance with the authorities [

75]. Trust appears in the literature as a two-dimensional concept, with separate parameters of legitimacy and competence, which will now be looked at in more detail [

78,

79].

3.4. Trust: Legitimacy

Legitimacy can be described as the willingness to be vulnerable based on the similarity of the intentions or values of another person or group [

80].

The legitimacy of emergency responders is built from a belief that the emergency services should be listened to and followed, as well as a belief that responders hold the wellbeing of the public as their main priority [

81,

82,

83,

84,

85]. Legitimacy has been explored extensively in recent years in relation to policing [

86] and is seen as crucial to eliciting compliance and cooperation with the lawful authorities, most specifically the police [

81,

82].

Refs. [

81,

82] state that for members of the public to see the police as legitimate, they must believe it rightful to follow the instructions of police officers and that they are exercising their powers appropriately. Refs. [

81,

82] therefore assert that legitimacy is (a) the belief that an institution exhibits properties that justify its power and (b) a duty to obey that emerges out of this sense of appropriateness. In the literature concerning mass decontamination, ref. [

14] also links public perceptions of legitimacy to increased co-operation from the public in relation to compliance with emergency response instructions; similarly, ref. [

5] states that increases in perceived emergency responder legitimacy will improve cooperation and compliance.

3.5. Trust: Competence

Confidence can be defined as the belief that certain future events will occur as expected given the actions of another group.

Ref. [

87] recognises the role of competence in building trust by studying healthcare professionals through the use of qualitative in-depth interviews with individual nurses and doctors working in primary care settings, identifying that a belief in a doctor or nurse’s competence was critical in their being respected and trusted to undertake their role. This will also be true regarding the public perception of whether the emergency services have the capability to effectively manage an emergency [

88]. Should the public not perceive emergency responders as being capable of effectively managing an incident, that is to say they do not view them as competent, then trust in the emergency responders will be diminished, and whilst the public may well still believe that responders are well meaning and legitimate in their efforts, they will not trust their instruction, not believing them to be capable of helping [

89]. If both legitimacy and competence are perceived as being present, then emergency services will be trusted, and as a result, their ability to influence risk perceptions and encourage co-operative behaviours will be greater [

89].

3.6. Communication

Communication is a crucial influencing factor of risk perceptions, with ‘risk communication’ being developed as a cross-disciplinary field which seeks to ensure that targeted audiences understand the risks potentially affecting them or their communities [

90]. Becker in [

91] states that risk communication “is vital for facilitating and encouraging appropriate protective actions, reducing rumours and fear, maintaining public trust and confidence, and reducing morbidity and mortality” (p. 3).

Effective risk communication requires the alignment of several factors between the communicator and the audience. In [

92], Fischoff describes the development of the risk communication field, tracing its course over the previous quarter of a century leading up to 1995. He identifies how, early on in the development of risk communication strategies, there was a strong focus on delivering accurate information to people with the belief that through this, these individuals and groups would be able to take this information, process it and, should they be effectively informed, come to a beneficial decision. As research progressed, the risk communication field moved towards strategies which sought to put the pertinent information required for beneficial development into the specific contexts at which it was aimed. More recently, again, an understanding has developed regarding the need for trust and relationships between those communicating risk information and those receiving these messages.

Risk communications theory has steadily looked to provide accurate and timely information, which it is believed will be heard by a receiver and rationally and logically divided into pros and cons, with a beneficial decision being made as a result. In [

93] Fischhoff and Scheufele clearly demonstrate this concept of thinking through the publication of their seminal paper “The Science of Science Communication”. Within this paper, they further propose the use of a mental model’s methodology in effectively communicating risk. Once again, the model utilises the concept of understanding what gaps exist and then looking to fill these gaps with pertinent information. As a result, the paper suggests that “effective science communications inform people about the benefits, risks, and other costs of their decisions, thereby allowing them to make sound choices” (p. 14033) [

93].

Ref. [

94] reviewed disaster management research, identifying that disaster warnings specific both to the culture and location of an audience, in contrast to more generic communications, improved compliance with any recommendations. Further factors, including the level of certainty with regards to the message, the familiarity and trustworthiness of the communicator and hearing the message reiterated through multiple sources, have also been suggested to enhance compliance with recommendations and advice [

95]. Numerous papers have also identified how the provision of accurate and timely information by responders, with regard to the threat being faced and information about why certain actions are being undertaken, will improve casualty compliance and operational outcomes [

5,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100].

Communications between casualties and responders is paramount to ensuring effective engagement between the two groups and therefore ensuring that trust with regards to both legitimacy and competency can be maintained and improved [

101,

102]. Ref. [

28] identified three key elements, during mass decontamination field exercises, for ensuring communications with members of the public are effective in increasing compliance, reducing anxiety and increasing perceptions of responder legitimacy. Casualties need to be provided with the following:

- (a)

Health-focussed information as to why decontamination is necessary;

- (b)

Information about what actions emergency services are taking;

- (c)

Enough practical information about what casualties should do during decontamination.

This research, therefore, once again highlights the efficacy of good communications in improving casualty behaviours during emergency incidents and, through this, in improving operational outcomes. Furthermore, ref. [

29] identified that communication needs to be both open and honest and be provided regularly to update the public on what actions are currently being taken. Such communications are linked to trust, both in relation to competencies and legitimacy, and will assist in encouraging co-operative behaviours amongst casualties [

103].

The literature suggests that communication needs to be focussed on why decontamination is required in relation to both the health of those involved, why the decontamination process is required due to the risk from any contaminant and why it will be effective in removing this threat [

29,

75]. It is essential that information is provided to allow members of the public involved in the incident to engage with the process of being decontaminated. Information must be communicated which provides casualties with details/instruction on what they are required to do in order to be decontaminated in an effective manner [

103]. Should communication be delivered in this manner, and provided that the above content be included, as set out in [

103], then casualties will be more co-operative and a more efficient and effective decontamination operation can be run.

There are also potential drawbacks with ineffectively communicating the negative aspects of an incident. It has also been noted that communications during Hazmat/CBRN incidents may also be used to downplay threats through over-reassurance. In such instances, this may lead to non-compliant behaviours, as members of the public may not see the need for interventions, such as decontamination, should the threat not seem sufficient [

9,

77].

There are some real-world Hazmat/CBRN incidents which have shown the importance of risk communication. During the nuclear disaster in 2011 at the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power station, both the Japanese government and plant operator TEPCO sought to reassure the public and provide limited pieces of information periodically, even in the face of this unfolding disaster. As [

104] states, “This is anathema to accepted crisis communication best practices. Experts recommend being truthful, forthcoming, and transparent throughout the crisis in order to remove uncertainty” (p. 1).

During Chernobyl, Soviet authorities delayed evacuation for 36 h and publicly downplayed the disaster for days, exposing thousands to avoidable radiation. At Three Mile Island, conflicting messages from the plant operator and government triggered the spontaneous evacuation of 144,000 people, far beyond what had been officially advised, fuelled by mistrust and media speculation. The Windscale fire saw UK officials secretly confiscating contaminated milk while publicly assuring citizens that no harm had occurred, an approach which later damaged government credibility when the truth emerged.

The lesson from these incidents is that effective risk communication shapes public perceptions and behaviours and can determine the success or failure of protective actions. By understanding effective risk and communication principles, emergency responders will be able to most effectively engage with members of the public and in doing so form the public’s perceptions of the threat and responses to any Hazmat/CBRN incident.

3.7. Risk Perception in Emergency Situations

As has been discussed above, there is often a focus on technological and organisational approaches to emergency response during emergencies and disasters, particularly Hazmat/CBRN incidents, while there is only limited recognition of what is required to enable the public to engage effectively with the response. Risk perceptions, therefore, have been shown by the literature to be an essential component of how risks are weighed. How, then, will risk perceptions during emergency situations influence decision making by members of the public caught up in them?

Hurricane evacuations present a useful parallel for investigating risk perceptions in Hazmat/CBRN incidents.

Both situations involve mass evacuations, forcing individuals to decide whether to evacuate or take protective measures. Hurricanes and Hazmat/CBRN incidents share elements of uncertainty and ambiguity, as well as psychological aspects like fear, anxiety, and social influence, which are similar in both contexts, influencing risk perceptions and decision-making.

Both scenarios entail perceived lethal threats, whether from a hurricane’s destructive power or from Hazmat/CBRN materials, affecting risk perceptions and responses. Factors influencing evacuation decisions, such as prior experience and information sources, are relevant to both hurricanes and Hazmat/CBRN incidents, as are lessons from hurricane warnings on clear and timely communication, which are also applicable to Hazmat/CBRN risk communication.

As such, studying how the public responds to evacuation orders and deals with the stress of hurricanes can inform our understanding of behaviour in Hazmat/CBRN incidents; we can leverage existing and more common hurricane research to enhance public preparedness and response strategies in Hazmat/CBRN situations.

Numerous studies have looked at the risk perceptions of members of the public in relation to hurricane evacuations, where people’s perception of the risk they are exposed to is a crucial consideration in their decision making process. Ref. [

105] investigated the evacuation of New Orleans following hurricane Katrina and identified a number of drivers which affected people’s perceptions, with uncertainty, lack of control and trust cited as three key areas. However, most importantly, it identified that it was the perceptions of the risk being faced that would influence evacuation behaviours.

A further parallel can be found in earthquakes, where studies have identified that actions relating to preparedness were positively correlated to a greater awareness of the risks of earthquakes. Actions ranging from higher levels of insurance cover through to stockpiling of food and medical supplies were more common in those who had a greater understanding of the earthquake risk [

106,

107,

108]. As shown by [

109], awareness of a risk and the associated recommended mitigating actions correlates to the greater preparedness of individuals and their likelihood of acting in accordance with recommended behaviours.

As already noted, the literature points towards a strong relationship between perceptions of risk relating to uncertainty and control and their influence on people’s decision making, and this has been noted during emergency situations. Ref. [

110] suggest that risk perceptions during emergency situations can develop along two different routes. There is an analytical and logical or rational pathway and an affective or irrational pathway driven by emotional and heuristic responses to perceived risks. Each of these pathways suggests a different process by which casualties’ will process risk information, and, as is made clear from the literature, that how casualties will perceive the risk facing them will significantly influence their decision making.

Human behaviour can be difficult to predict, and this is even more true during emergency situations, where those involved will be stressed and anxious in the midst of what are often very chaotic events [

111,

112,

113]. There are a number of theoretical frameworks proposed within the literature to help explain behavioural responses to a threat. Many are based on the promotion of health behaviours, and many identify that such behaviours are motivated by threat perception and the intent to avoid adverse outcomes. Such approaches have also been explored in relation to Hazmat/CBRN and mass decontamination events [

35].

Protection motivation theory [

114] and the person relative to event approach [

115] suggest that self-protective behaviours will be undertaken as a result of a perception of a risk being faced and an evaluation of a person’s own capability to undertake said protective behaviours (response efficacy and self-efficacy) in relation to a hazard.

The Protective Action Decision Model [

116] specifically looks at human behaviours during emergencies and disasters in relation to taking action in preparedness for or responding to an ongoing event and often focuses on the issue of evacuation. The model suggests that risk appraisal and the perceived efficacy of certain protective actions influences individuals’ decision making, with risk appraisal comprising the perceived expectations of both the likelihood and severity of a hazard being faced as well as its imminence and the extent to which the severity of the hazard would directly impact one’s own personal safety, either in the sense of physical harm, the potential loss of property or disruptions to their lifestyle [

106].

The Social Attachment Model [

117] has also been suggested for explaining human behaviour during emergencies and looks at the immediate response to disastrous events. The Social Attachment Model is a psychological theory that describes how humans form and maintain social relationships. The model postulates that people have an innate need for close, secure relationships and that this need influences their thoughts, emotions, and behaviours in their social interactions. Ref. [

118] reported on studies which had looked at responses to earthquakes, identifying that individuals will be more likely to seek shelter with those familiar to them rather than evacuate and that this behaviour was conscious, rational and adaptive.

Risk perceptions also appear in the literature, with emergency and disaster decision making considered to be strongly influenced by sociodemographic factors. This suggests that people’s willingness to adopt certain preparedness measures will also be impacted by the previous experiences, beliefs and attitudes of different sociocultural groups [

119]. Refs. [

120,

121] suggested that the reason for differences in disaster preparedness and actions taken during an emergency between different sociodemographic groups was due to different populations having differing propensities to take action to improve preparedness or to take protective behaviours during a disaster. Other factors including previous experiences of emergencies or disasters have been suggested to motivate people in the adoption of advised protective behaviour [

122,

123]. However, conversely, others have suggested the opposite effect in what is referred to as the experience–adjustment paradox. This phenomenon has been suggested to occur following experiences of incidents which did not result in any major impact and as a result left those having experienced such events to perceive the risk of future such incidents as lower as a result [

124,

125]. As such, previous experience of an incident is likely to influence risk perceptions, which may either increase or decrease the likelihood of taking protective actions and following advice.

Furthermore, the literature appears to confirm the influence of the perception of risk on casualties’ actions during an emergency, including their willingness to co-operate during a mass decontamination incident.

The questions which now arises and is most pertinent to this paper is as follows: to what extent is it possible for emergency responders to influence casualties’ perceptions of risk and encourage co-operative behaviours?

3.8. Risk and Decision Making Pathways

The literature identifies risk perception as being crucial in how those involved in emergency situations will make decisions. Elements such as affect, trust and communications appear crucial in informing how people will perceive risks, especially in unfamiliar and uncertain emergency situations. Such risk perceptions in turn influence the levels of co-operation of those involved in an emergency with regards to their willingness to provide any emergency advice or instructions.

In their summary of key findings on emergency response, ref. [

28] found that the public processes risk perceptions in two broadly dichotomous approaches. These approaches can be grouped into ‘irrational ’or ‘rational’ approaches, or more affective approaches and more cognitive approaches, as described by [

51], who, in addition to identifying these distinct [

28] approaches, noted their ability to influence each other.

3.9. Irrational Pathway

Approaches that make assumptions about ‘affective’ public behaviour during emergencies suggests that people will panic, act instinctively, and be unable to make informed decisions about the actions they should take to protect themselves [

126,

127]. These approaches emphasise the high levels of anxiety that people will experience and the accompanying negative impact of this on their ability to take recommended action.

Proponents of theories that suggest more affective responses within public behaviour suggest that the lack of control, unfamiliarity and uncertainty inherent to emergency situations will result in an emotional, anxiety-based response, which will be the major factor affecting public behaviour. In line with this, ref. [

56] describes the essential role of affective decision making as the “fast, instinctive and intuitive reactions to danger” (p. 24), and it has been suggested that these rapid, affect-based processes drive behaviour in situations where people are confronted with a risk for which they have insufficient knowledge or time to use more time-consuming cognitive processes [

48].

Factors that may affect the way in which the public interpret risk are identified in [

128], particularly with regards to the extent to which the risk is

- (i)

Perceived as voluntary (voluntary risks are more acceptable than involuntary risks);

- (ii)

Personally controlled (personally controlled risks are perceived as less risky than those controlled by others);

- (iii)

Familiar (familiar risks are perceived as less risky than unfamiliar risks).

Risks that are perceived as being involuntary, uncontrollable and unfamiliar are perceived to be the riskiest and are sometimes referred to as ‘dread’ risks [

128]. Such dread risks are therefore seen to lead to more affective processing, given the lack of information and understanding, and therefore, a reliance on affect for decision making is more likely; as [

56] state, “reliance on affect and emotion is a quicker, easier, and more efficient way to navigate in a complex, uncertain, and sometimes dangerous world” (p. 24). These approaches therefore envisage behaviour during emergencies as emotional and instinctive, resulting from the anxiety people will be experiencing, and are largely pre-determined, i.e., people will behave in a certain way and the role of responders will be to manage that behaviour.

Likewise, ref. [

129] identified two systems used in decision making: ‘fast think’ and ‘slow think’. The latter is a measured process involving a conscious cognitive process whilst the former is a quick automatic reflexive process which does not require any conscious effort. Emergency situations are characterised by a lack of control, unfamiliarity and uncertainty, and this results in an emotional, anxiety-driven response [

10,

99]. This, it is has been suggested, will be the primary factor driving public behaviour [

48,

51].

The literature also highlights a lack of control, uncertainty and unfamiliarity as likely to be highly prevalent in casualties during any Hazmat/CBRN or mass decontamination operation. This can be due to the fact that it may take a significant amount of time for the emergency services to fully identify the agents and substances involved and subsequently to determine appropriate further interventions with which any casualties will have no choice but to comply. All of this will be beyond the experience and knowledge of most casualties involved, and hence, members of the public will likely be anxious in the face of these uncertain and unfamiliar risks. It is likely that the unfamiliarity, uncertainty and lack of control will generate high levels of anxiety [

36].

Anxiety can be understood as a “tense, unsettling anticipation of a threatening but vague event; a feeling of uneasy suspense” (p. 3) [

130]; importantly, it is distinct from fear as it is without an “identifiable threat” (p. 29) [

131]. Incidents involving Hazmat/CBRN materials which require casualties to be decontaminated are particularly likely to invoke anxiety, as such incidents will give people limited control of a situation of which they also have a limited understanding [

10,

99,

132].

The need for effective management and communications in order to manage anxiety and improve co-operative behaviours was identified in [

131], which also emphasised that whilst anxiety and fear are to be expected, panic is not. Crucially, panic, unlike fear or anxiety, involves an irrational state [

19] and has been shown to be a rare occurrence during major incidents [

133,

134,

135]. Whilst panic and the associated irrational behaviour may be considered rare, this does not necessarily equate to any certainty that casualties will co-operate with responders. Anxiety and fear, both of which are likely to be present [

131], may well impact co-operative willingness, as may a wide variety of other factors.

Two systems with which people may process information were identified by [

45]: the ‘fast think’ and ‘slow think’ systems. The former is a reflexive process that happens very quickly and that does not require conscious effort, while slow think is the reverse and involves a conscious cognitive process. Decision making is viewed as occurring after careful weighing of the advantages and disadvantages, with risk communication looking to influence this. However, the role of affect in decision making has come to prominence [

56,

136,

137]. As such, risk communication has begun to focus more on ‘fast think’ when seeking to understand how people make risk-based decisions.

The more affective approach therefore is seen as being likely to be taken during emergency situations due to high levels of uncertainty, unfamiliarity and lack of control driving anxiety. This will see individuals utilising their emotions and feelings, and as a result, it will make communications and rational engagement from emergency responders seeking to encourage effective protective behaviours difficult at best, if not unachievable. Consequently, strategies to contain and control people during emergencies are viewed as being required in order to undertake any form of emergency management.

3.10. Rational Pathway

The ‘irritational’ or more affective approaches assume that people involved in emergencies will be prone to panicking and that they will be likely to act instinctively, whilst being less or completely unable to make rational decisions in relation to what actions they need to take in order to protect themselves [

126,

129]. However, while such theories have largely been discredited within the literature [

138,

139], they still inform aspects of operational planning for mass decontamination response, with the myth of mass panic still persisting given its potential to cause negative consequences as far as providing information on strategies and tactics which may inhibit an emergency response is concerned [

101,

140].

As a result of this thinking, there has been a lack of planning regarding how to communicate to those who may be caught up in a mass decontamination incident. Mass panic refers to an irrational level of response to a perceived threat whereby those involved have lost the ability to act rationality or with any form of self-control. Furthermore, there is the idea that mass panic spreads like a “contagion,” and, as a result, all of those involved will begin to lose rational processing abilities, leading to unrest and unthinking behaviours within any group or crowd [

141,

142,

143,

144,

145]. As stated by [

146], emergency incidents “bring out the worst in people” (p. 556). However, while research shows that actual examples of panic during Hazmat/CBRN incidents are rare, it can also be seen that members of the public believe that a) they would be unlikely to panic, and b) they believe others would be likely to panic [

147].

An article on Wikipedia summarises this popularist view, stating that “Scenes of mass contamination are often scenes of collective hysteria, with hundreds of thousands of victims in a state of panic. Therefore, mass decontamination may require police, security, or rescue supervision to help control panic and keep order” [

148]. Such views also permeate emergency service policy, as shown by [

149], who state that “A challenge [during incidents involving mass contamination] is that of rapidly establishing and maintaining an impermeable cordon of sufficient size to contain the population in an area of high population density following an incident that may cause distress and panic” (p. 60). However, as [

27] has shown, such beliefs, leading to strategies which look to control people, are counterproductive. The research in this area has, for several decades, pointed to the behaviour of casualties in emergency and disaster situations being co-operative and socially structured, dispelling the myth of mass panic and irrational behaviours [

21,

133,

150,

151,

152].

Alongside the concept of mass panic, there is also the theory that casualties caught up in emergencies and disasters will become helpless as a result of the incident stunning or shocking them into a state where they are then unable to heed any advice or take any action to help themselves or those around them [

153]. The authors of ref. [

27] argue that theories of panic and helplessness allow for authorities to utilise authoritarian command and control strategies, believing casualties as being unable to act as partners in response and instead as something to manage. As such, withholding information is seen as being a justified approach to minimise panic, and there is a belief that efforts to communicate will be wasted. The authors of ref. [

27] go on to highlight how this fear of mass panic has led to code words being used in public arenas and why the public will not be told about a fire [

140,

154]. Further to this, ref. [

155] identifies how such concerns about panic has led to policies within the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), among other measures, which instruct on the withholding of information from the public about Hazmat/CBRN incidents and on what actions the public would need to take in the event of an incident.

Myths about irrational and counterproductive public response to emergencies can therefore significantly hinder and exacerbate emergency preparedness and response. Ref. [

27] recognises how, in response to Hurricane Katrina, the consequences of fear about looting led to a focus on a military rather than humanitarian response, with disastrous impacts for residents of New Orleans [

139,

152]. Ref. [

27] argues that these myths and associated strategies of restricting information from the public and thus of limiting the public’s ability to partake in their own safety reduce the public’s trust in responsible agencies and reduce their own sense of agency and the perception of their ability to cope with any emergency situation [

8,

156,

157].

More cognitive or rational approaches recognise this and suggest that rather than exhibiting panic, members of the public involved in an emergency will remain rational and maintain normative behaviours [

139,

158] and that the approach taken by emergency responders in the management of an incident will influence the behaviours of those involved.

The literature points to the role that trust can play in influencing the decision making of members of the public during incidents. Ref. [

3] suggests that the greater the levels of trust the public holds for emergency responders, the more willing they will be to follow advice and recommendations.

Ref. [

29] categorises legitimacy as the belief that responders are acting fairly and in line with the best interests of the public. Competency is then based on the perception of the public that the emergency responders have the ability to effectively assist them and manage the incident. Ref. [

50] recognises that for trust to exist responders must be perceived as both competent and legitimate. Holding and maintaining trust will then increase public compliance and co-operation with emergency responders and the instructions they give [

4,

29,

75].

The literature identifies that the actions of responders during an emergency will influence trust, with effective communication being of particular significance. To enhance trust, communication should be open and honest, seeking to explain the actions required for those involved to protect themselves and why protecting themselves is required. Sufficient practical information is also required so that the recommended actions could be effectively undertaken by those involved [

5,

159]. What is clear from the literature is that how emergency responders manage an incident will directly impact casualty behaviours and, as a result, impact the likelihood of co-operation, which will be a major factor in the success of any emergency response [

3,

4,

14,

29,

75,

77,

160,

161,

162].

In conclusion, this literature review shows that there is a need for first responders and managers to understand public behaviour and plan accordingly, with effective tactics and strategies being used in order to assist the public. However, even though the current research has shown the concept of mass panic to be unfounded, this idea still plays a large role in the perceptions and preparations of emergency responders and planners [

27,

163].

The strategies and tactics utilised by emergency services have often been based on these wrongly held assumptions of public panic, and as a result, strategies have revolved around containing and controlling the public [

27]. Sharing of information and reassurance have been deemed as not necessary, or even potentially harmful, with the public being viewed as unlikely to cope with receiving this information [

157,

164]. This has resulted in effective strategies for engaging with crowds not becoming part of responder training or awareness.

There is a need, then, to understand how to avoid creating perceptions of mistrust and illegitimacy, both of which are likely to contribute towards a lack of compliance and to threaten the potential for an orderly and effective operation [

165,

166]. Theories of mass panic and its consequential operational outcomes can only serve to potentially worsen a situation and reduce compliance and positive affective feelings and should therefore be discounted and discouraged from use by first responders or emergency planners.

3.11. Mass Decontamination and Crowd Behaviours

Mass decontamination operations will involve interaction between emergency responders and larger groups of people. For this reason, where human behaviour during mass decontamination has been studied, this has most often been considered in relation to crowd behaviours [

4,

5,

75].

Mass decontamination events are characterised by large numbers of people in a single location and as such must be considered to be crowd situations. As a result of this, and the significant impacts and difficulties that large numbers of casualties will present over smaller-scale incidents, crowd theories have been the focus of inquiry when considering the question of casualty behaviour. Therefore, alongside an understanding of individuals’ risk perceptions and decision making, which have already been explored in this paper, the literature surrounding how these factors will be impacted in relation to crowds should a mass decontamination incident occur will also now be considered.

Theories of crowd behaviour can be traced back to the author of [

126], who introduced the irrationalist approach in his 1895 book Psychology of Crowds. However, the concept of mass panic has since been widely discredited, as there has been little support for it. Ref. [

135] argues strongly for how, during disasters, behaviour is often socially structured. By the 1960s these theories of mass panic in crowds had been largely dispelled and more rationalist approaches such as Emergent Norm Theory had begun to be developed [

166]. Ref. [

134] detailed the behaviour of people evacuating during a fire at the Beverly Hills Supper Club and was able to detail how those escaping through fire exits still waited in a patient and orderly manner even when these exits were crowded and evacuation of the premises was required. Instead of panicking, those inside maintained their usual social principles as they waited to escape. These theories have since been developed further, and by the 1980s, the social identity approach had begun to be considered [

167].

The social identity approach appears most prominently in the literature in describing the likely crowd interactions during a mass decontamination incident [

4,

5], and it explains likely group behaviours during such incidents [

28]. The social identity approach suggests that people will have a personal and social identity and that their social identity is built on their membership in groups. People’s perception of who does and does not share their social identity influences how they will interact with others.

A shared social identity results from a perception that an individual is similar to others in a group, with factors such as proximity to others, a shared sense of fate, or a shared perception of a threat. These factors are all likely to enhance the likelihood of an individual categorising themselves as similar to others. Within mass decontamination incidents, such a shared identity is likely to influence people’s willingness to co-operate with others in their group and maintain the social norms of the group, as well as their willingness to engage with emergency responders [

109]. During the London 7/7 bombings [

168], it was shown that many members of the public who had been caught up in the explosions but were not significantly injured offered assistance to those in need around them rather than considering their own needs and wellbeing following their exposure to the attack.

3.12. Effective Decontamination

The final section of this literature review looks at the literature relating to understanding what actions are required to facilitate the effective management of decontamination incidents.

The literature has identified a number of crucial elements that need to occur in order to facilitate the effective management of a decontamination operation. Ref. [

28] explored the effective management of decontamination operations by looking at findings from smaller-scale decontamination incidents, the literature relating to the decontamination of members of vulnerable groups, focus groups involving members of the public, mass decontamination field exercises and mass decontamination online and visualisation experiments. As a result, ref. [

28] identified five conditions required to effectively manage a mass decontamination incident:

It will be necessary to ensure that members of the public requiring decontamination agree to undergo decontamination;

Good management will also help people to effectively go through the decontamination process;

It will also be necessary to ensure that they co-operate with others during decontamination;

Reducing anxiety will also be crucial;

Supporting those who may need additional support to undergo decontamination will also be necessary.

Given the nature and scale of mass decontamination in relation to the number of casualties involved, it will be necessary to ensure that those who need to be decontaminated will agree to undergo this process if it is to be successful. Given that the actions required from the public will involve disrobing and undergoing a decontamination shower, this may be difficult [

86] and it is likely that those involved will not readily agree to undertake such actions [

169,

170,

171]. In field exercises, those participating as casualties have provided feedback that they did not feel they had enough information to do what was being asked and that they were often confused by what emergency responders wanted of them [

3,

14].

The unwillingness of casualties to undergo decontamination is only likely to be exacerbated in situations where those being required to undertake decontamination do not feel they have been properly informed of what actions are required of them in the decontamination process and where issues such as privacy have not been duly considered [

5]. In order to ensure that those needing to undergo decontamination will agree to this process, it will therefore be essential that they are effectively communicated with so that they understand why they need to undergo decontamination using a health-focused explanation of how it will reduce the risk to them of further harm from the contaminant and also the risk to others from contamination [

5,

29]. It will also be important to ensure that they feel that their concerns are being heard and considered [

4].

Alongside explanations of why decontamination is needed, as well as why it is necessary to communicate concerns for casualties’ privacy and welfare, casualties also need to be provided with practical information in order for them to carry out the actions required to effectively achieve decontamination. Such actions by responders will show to the casualties involved that the incident is being managed both legitimately and competently, thus improving trust in emergency responders and increasing the likelihood of their instructions being heeded [

89].

Ref. [

3] found that casualties who had been given the most detailed information were able to complete the decontamination process more quickly and efficiently than those provided with less detailed or no communication on what actions needed to be taken. This finding clearly demonstrated the need for emergency responders to be prepared and capable of providing those needing to undergo decontamination with sufficiently detailed information about what is required of them during the decontamination process.

3.13. Narrative Literature Review Limitations

Alongside the advantages discussed, it is worth noting the limitations of the narrative approach. Amongst them, the larges limitation is that it is not a systematic approach, and hence the selection of studies, data extraction, and the synthesis of the findings are to some extent subject to the author’s biases or personal preferences [

31,

172,

173]. However, as discussed, the use of reflexivity can ameliorate this and support a narrative approach’s by giving the reviewer the ability to seek a wider range of studies and more diverse studies as a result [

31,

172,

173].

A narrative literature review may also have a limited search strategy due to the lack of a systematic approach, leading to the possible exclusion of relevant studies. Alongside potentially missing relevant studies, narrative literature reviews do not usually include a formal quality assessment of studies included in the review, and consequently, studies of varying quality may be included [

31,

172,

173].

There may also be a lack of transparency in how the review is conducted, again due to the narrative literature review not following a systematic approach. As such, it may be difficult for readers to understand how the review has been conducted and how the findings have been produced [

31,

172,

173].

In summary, while narrative literature reviews can provide a useful overview of a research area or topic, they have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. However, overall, the advantage of the narrative approach, that it allows for a wide review of the literature to reveal new insights not previously explored within the field of mass decontamination, outweighs these drawbacks.

3.14. Modelling of Casualty Behaviour

It is worth now briefly covering mathematical and computational modelling, which has become increasingly important in simulating human behaviour during emergency evacuations including mass decontamination events. These techniques enable scenario testing when live experimentation is impractical or unethical. Agent-based models (ABMs), for instance, simulate individuals as autonomous agents responding to their environment, allowing for the study of evacuation dynamics, route choices, and behavioural variability. Such models have incorporated psychological realism modelling disorientation or injury to reflect the complexity of human response.

Ref. [

174] developed an ABM using fuzzy clustering to assign rescuers dynamically to clusters of evacuees. Their simulations demonstrated how optimised responder allocation increased evacuation throughput under constraints. Meanwhile, ref. [

175] introduced the “Digital Twin” concept, pairing live operational data with simulations to forecast system behaviour and test emergency protocols in real time.

Other models integrate physical hazard dispersion (e.g., chemical plumes) with behavioural reactions, such as the CFD-ABM hybrid used by [

176], which showed how crowd dynamics interact with environmental spread. Additionally, optimisation frameworks such as those used by [

177] adjust behavioural parameters (e.g., exit-switching thresholds) to identify strategies that reduce total evacuation times.

Practical examples for mass decontamination include [

178], who modelled UK decontamination data to pinpoint bottlenecks in the process delivered by UK Fire and Rescue Services. Their findings led to improved re-robe capacity planning, demonstrating how simulation directly informs preparedness.

To summarize, computational models, especially those that blend behavioural insights, with system-level simulations, offer powerful tools for “what-if” scenario testing, resource optimisation, and training. Their continued integration with social science perspectives will be essential to improving operational response during CBRN and Hazmat emergencies.

4. Discussion

This literature review has sought to explore the literature which relates to the study of casualty behaviour during mass decontamination operations in response to Hazmat/CBRN incidents.

Understanding how individuals and groups respond during such events is essential for designing effective strategies for decontamination and mitigating distress to those requiring decontamination. Several psycho-social factors have been explored in the study of casualty behaviour in this context; however, there are notable gaps in the current research.

4.1. Risk Perceptions, Trust and Rationality: The Cognitive Behavioural Approach

A large part of the literature examined explored themes such as risk perceptions, the role of trust and the rationality of casualties during emergencies.

These themes fall under the cognitive–behavioural approach, which emphasises the role of thoughts, emotions, and behaviours in shaping responses to mass decontamination. The literature in this section examined how individuals process information, perceive and assess risks, and make decisions during the decontamination process.

Understandings from the cognitive–behavioural approach have been used to develop tailored interventions for improving casualty behaviour during decontamination. These interventions have looked to target specific cognitive biases, fears, or anxieties that individuals experience as factors that contribute to psychological resilience can inform training and preparedness efforts by helping to understand how individuals cope with stress and uncertainty.

While the areas covered by the literature associated with this approach provide valuable insights into individual decision making, they do not fully account for the social dynamics and group behaviours that can influence casualty behaviour during mass decontamination.

Furthermore, research which has explored cognitive-based approaches has too often relied on controlled simulations or hypothetical scenarios. While these are valuable, they may not fully capture the complexity and emotional intensity of real-world mass decontamination situations.

The literature surrounding cognitive processes does not always, therefore, translate to accurate predictions of how individuals will behave in high-stress situations. People’s responses can be unpredictable, and factors beyond cognitive processes, such as past experiences and personality traits, also play a role.

This approach also does not adequately consider cultural and contextual differences in how people perceive and respond to risk and threat, which can vary significantly among different populations.

Therefore, whilst the areas explored in the literature within the cognitive–behavioural approaches provide valuable insights into individual decision making and cognitive processes during mass decontamination, there is a need for these various factors to be considered more holistically with elements such as risk perceptions, trust and communications, all considered in relation to each other in order to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of casualty behaviour in such scenarios.

4.2. Mass Decontamination and Crowd Behaviours: The Social–Psychological Approach

The literature review also explored mass decontamination in relation to crowd behaviours within what can be described as the social–psychological approach. This explores the impact of group dynamics, social influence, and communication on casualty behaviour. It considers how individuals’ decisions are influenced by the presence and actions of others.

This element of the literature recognises that behaviour during mass decontamination is not solely determined by individual decisions but is significantly influenced by group dynamics, social norms, and interactions, with the literature acknowledging that people are not isolated actors but part of a social context.

The literature in this area considers the impact of others’ actions, peer pressure, and cooperation or conflict within groups, and highlights the importance of effective communication and the role which emergency responders can have in shaping behaviour.

The literature pointed towards how social–psychological approaches can inform strategies to prevent and manage undesirable behaviours by understanding social dynamics and developing interventions that promote cooperation and compliance; it indicated that such approaches can also be adapted to consider the diverse needs and responses of different population groups, such as children, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities.

However, casualty behaviours in group settings can be unpredictable and will be context-dependent. It is therefore difficult to predict how a specific group will behave during an emergency.

It is also true that the elements of the social–psychological approach, much like the cognitive approach, will not operate in isolation. The elements of the social–psychological approach will interact with individual cognitive processes, emotional reactions, and situational factors.

In conclusion, the social–psychological approach offers valuable insights into how group dynamics and social factors influence casualty behaviour during mass decontamination. However, as stated, for the cognitive behavioural approaches, these areas should be combined with other psychological approaches and practical insights to create a comprehensive understanding of behaviour in these complex and high-stress situations.

4.3. Cultural and Societal Factors

Another area which is involved in the other two approaches and is often mentioned within practical guidance can be summarised as culture and societal factors. Here, the literature refers to the importance of understanding the cultural and societal factors which influence casualty behaviour. Different cultures may have varying perceptions of risk, trust in authorities, and expectations during decontamination.

Research has often under-considered the cultural and contextual aspects of mass decontamination, such as the diverse needs and responses of different population groups, including children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. Indeed, it does not stand out in the literature review as a single topic but is rather found as part of discussions within other areas.

When it has been considered, the cultural and societal context within the literature emphasises the influence that cultural, social, and contextual factors will have on casualty behaviour during mass decontamination incidents, providing valuable insights into how different populations may perceive and respond to such events.

The literature underscores the importance of considering cultural diversity in emergency planning and allows for the development of tailored interventions and communication strategies that are sensitive to the needs and beliefs of diverse populations. This can improve the effectiveness of response efforts. However, cultural and societal factors are highly complex and diverse; therefore, understanding and addressing the needs of various cultural groups within a community is both challenging and resource-intensive.

There is also a risk of overgeneralizing cultural behaviours and responses, particularly when assuming that all members of a particular group will react in the same way and when it is not fully comprehended that people within the same cultural or societal context can have diverse reactions.

While this approach helps identify cultural and contextual factors that may influence behaviour, it may not always predict specific behaviours during mass decontamination incidents, as individual responses can vary widely within cultural groups.

Furthermore, the tailoring of response tactics and strategies for different cultural and societal contexts will require a high level of additional resources, which will be a strain on emergency response organisations, especially in large-scale incidents.

5. Conclusions

A nightmare scenario for society is a CBRN attack in a densely populated urban areas, as the Sarin gas attacks in Tokyo showed. It is imperative, therefore, that city and urban planners consider how to effectively manage a response to such threats, including the use of mass decontamination, should they materialise.

This paper critiques the relevant literature associated with both cognitive–behavioural and social–psychological approaches, as well as cultural and societal factors. Using a narrative approach, a broad range of the literature that considers how casualties respond to emergencies in general and to mass decontamination in particular was assessed, and two major shortcomings revealed.