1. Introduction

Germany is one of the countries in the European Union where the government takes a strong stance on shop operating times. In 1956, the Shops Closing Act (Ladenschlussgesetz/LadSchlG §12) was passed at the federal level that for most of the last seven decades forbade retailers to open their shops on Sundays and public holidays [

1]. In the 1980s and 1990s, long Saturdays and long Thursdays were introduced, but these did not affect Sunday opening hours. A decisive change came in 1996 with the nationwide liberalization of shop opening hours on weekdays, but Sunday opening hours remained heavily regulated [

2]. Since 2006, legislative authority for store opening hours has rested with the federal states [

3] and each federal state has been able to decide independently on exceptions for Sunday opening [

4].

Since 2003, shops have been allowed to be opened on four Sundays per year if there is a fair taking place in the same city or quarter. However, even before 2003, exceptions could be granted, and shops were allowed limited opening times on Sundays, e.g., on the Sundays before Christmas. The Shops Closing Act has been passed on a federal level, while its realization happens on the state level. Thus, regulatory differences between the states occur as detailed below for Berlin (BerlLadÖffG §2) and North Rhine-Westphalia (LÖG NRW §5). In coastal regions and cities in northern Germany, special state regulations (Bäderregelung/Bäderverordnung) allow for significantly more frequent and extended Sunday opening hours for shops in tourist areas. These exceptions only apply to certain product ranges and periods and are linked to recognition as a tourist destination [

5,

6].

In the past, usually, every deregulation has been met with very restrained opposition. Neither in 2003 nor in 1996, when the shop closing times on working days were relaxed significantly, did any noteworthy protests flare up [

7]. Since 2006, in Germany, the regulations on Sundays and public holidays open for business have been determined by the federal states themselves. The following applies to all federal states: special occasions such as festivals, trade fairs, markets, or similar events are a prerequisite for opening sales outlets. Opening hours and the number of days vary from state to state: often 4 days a year from 1 p.m. and no longer than 5 h (North Rhine-Westphalia), but in Berlin, for example, 10 days a year with opening hours from 1 p.m. to 8 p.m. [

8,

9]. Those Sundays where shops are allowed to open are furthermore referred to as retail Sundays. Ziegler [

10] provides a summary of the legislation across the different German states.

In the most populous federal state in Germany, North Rhine-Westphalia, with 18 million inhabitants, there is a public interest in Sundays open for business. Interest arises due to openings taking place in connection with local festivals, markets, trade fairs, or similar events. They serve to maintain, strengthen, or develop a diverse range of stationary retail outlets or central service areas, and serve to revitalize city centers, town centers, or district centers. Also, they increase the visibility of the respective municipality as an attractive and livable location, particularly for tourism and leisure activities, as a residential and commercial location and as a location for cultural and sporting facilities [

11,

12]. Retail Sundays, therefore, not only help to make leisure activities more attractive for the local population but also contribute to the volume of tourism, both for overnight guests and for day tourism in the regional context.

If arguments against retail Sundays are raised, they are most prominently being vocalized by members of the established Christian churches and union representatives [

13,

14]. Churches emphasize the protection of Sunday as a day of rest, which is under special protection for reflection and time spent together with family and society—both religiously and culturally. They refer to the Basic Law and the biblical commandment to

keep Sunday holy [

15]. In public statements and lawsuits, churches regularly express criticism of planned extensions to Sunday opening hours and raise their objections in legislative proceedings and public hearings [

16,

17]. They also file constitutional complaints and lawsuits against overly permissive regulations, such as Berlin’s shop opening laws or new regulations in the federal states. This also leads to alliances such as the Alliance for a Free Sunday, in which they work closely with trade unions to defend Sunday protection [

18]. Trade unions in Germany, especially ver.di, advocate for a work-free Sunday to protect retail workers and see Sunday work as a burden on the work–life balance. They argue that Sunday rest is a key element in the quality of life and health of employees. Legal action is also being taken, with numerous lawsuits being filed against Sunday openings, often in conjunction with the churches, and in many cases these have been successful in administrative and constitutional courts [

19]. These lawsuits have led to many planned Sunday openings being prohibited or restricted. Trade unions are also trying to organize petitions and public campaigns to draw attention to the importance of Sunday protection and exert political pressure [

10].

With a continuing increase in online retail, and thus the revenue generated by stationary offline stores stagnating [

20], more and more consolidation of offline retail can be witnessed [

21]. This holds true, in particular, in the city centers of major German cities [

22] where, in the last decade, rent prices have converged to rates beyond the national inflation rate [

23,

24] and are already considered mortal dangers for small shops.

City officials thus hope that retail Sundays, together with events, might draw customers back into the city centers and thereby increase the revenues of stationary stores [

25]. This perception does, however, not remain unchallenged [

26]. For people, especially families where both partners are working full-time, retail Sundays offer the additional benefit that shopping can be realized in a less stressful manner over the course of two weekend days. This might increase the motivation to frequent stationary retail stores more often. With advances in self-service registers, grocery or hardware stores especially could afford the additional opening hours with only minimal increases in their personnel costs.

While most of the preceding discussion is conjecture, Poland provides an ideal case study from an inverse perspective. In 2018, the Polish government decided to follow the German example and introduce legislation forbidding shops from opening on Sundays [

27]. This ban was put into action over the course of the next three years. Grzesiuk [

27] provides an evaluation of the effects resulting from the regulatory switch. They attest to the regulation having some positive aspects. However, they also acknowledge that these effects did not result from the regulation alone but are the consequence of multiple actions and the fact that in the middle of the period under consideration the COVID-19 crisis took place. With the publication of their study in 2021, they cannot put the end point distinctly after the COVID-19 effects, and thus no conclusive evaluation is possible. Another study by Rizzica et al. [

28] focuses on Italy and takes a comparative view of a more dynamic nature. They consider how the type of employment changed in relation to relaxations of Sunday opening times. Considering a time frame of almost thirty years, they provide the most long-term consideration of this topic.

Similar to Poland, Romania in 2015 passed legislation restricting trading on Sundays and during certain nighttime hours. Comparable to Germany, in Poland, the Catholic Church took an active stance in getting this regulation passed [

29]. In their study, Kovács and Sikos [

30] consider the short-term effect of this regulation, i.e., the effect during the first year after adopting the new regulation. In this context, it needs to be stressed that in Romania the ban was immediate, whereas in Poland, it was established over the course of almost three years. A comparable strong stance against retail Sundays is taken by the church in Croatia [

31] and the unions in France [

32]. Even the United States, which on average reports rather limited labor and market regulations due to Christian influences, has realized bans on retail Sundays in certain states [

33]. The UK and the Netherlands followed the way of relaxing their shop closing time laws, and the UK allows the general opening of shops on Sundays during a given period. In the Netherlands, the situation differs whether the shop is in a touristic area, where they are allowed to open normally. In non-touristic areas, the Dutch regulation is comparable to the German one, allowing opening only during twelve Sundays each year. Those retail Sundays, however, do not have to occur with fairs or other events [

34]. Regarding France, Maurin and Goux [

32] provide a study that considers the effects of the relaxation of the French shop closing law in 2016, which impacted 30 of the French regions. They come to the conclusion that the amount of retail staff remains approximately the same, but utilization patterns change. The study by Ebrey and Cruz [

35] is one of the few studies to take a comparative view and report on the perception of working on the weekends by workers. Among the few studies that consider the economic effects of retail Sundays, a study by de los Llanos Matea and Mora-Sanguinetti [

36] stands out, as they focus not only on the single retailer or the city level but consider macroeconomic effects of retail Sundays, or rather on the economic losses incurred by restricting retail on Sundays.

For Germany, only a limited number of scientific studies on retail Sundays exist [

7,

10]. The study by Grzesiuk [

27] on Poland’s introduction of a shop closing act is the only study that, even though unintentionally, talks about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumers’ perception of retail Sundays. The results of the study by Haensch and Kratzer [

37], conducted before the COVID-19 crisis, and the study by IHK NRW [

38], conducted decidedly after the crisis, hint at only marginal changes among the German population, in particular the population of North Rhine-Westphalia, but there does not exist a scientific study on the changing perceptions. Thus, adopting an exploratory perspective, the objective of this study results in the form of the following research question: How far did consumer perceptions of retail Sundays in Germany change due to the COVID-19 pandemic, i.e., in particular, between 2018 and 2025?

By answering this research question, this study adds to the existing literature in three ways. It recapitulates the current state of perceptions among the population of one of Germany’s major cities. In the years following the pandemic, very little research on Sunday opening hours has been published; most of it has not been published in scientific journals. Thus, aside from the two studies on Poland and the U.S., no other scientific study considers the status quo in post-COVID-19 times. All publications that do exist adopt a static perspective and remain purely descriptive. Thus, this study is the first that in a European context analyzes changes in the population by comparing the status quo before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The robustness of all results regarding gender, age, and origin has been considered. Retail purchases are driven by hedonistic and utilitarian motivations [

39]. Thus, following Kim [

40], who applies the concept to inner city retail, the study differentiates the reasons for attending retail Sundays into hedonistic (shopping for fun and attending events) and utilitarian (finishing chores) motives. It, thus, provides a more sophisticated and diverse look at the topic than the one adopted by previous studies.

The city of Cologne has been chosen as the object of study for three reasons. Considering the population size, Cologne, as Germany’s fourth-largest city, is placed neatly between Hamburg and Munich as well as Frankfurt and Düsseldorf. It thus represents a large share of the German population. Together with the other three cities that report more than one million inhabitants, Cologne is also one of the most tourist-visited cities in Germany. With its geographic location in the western part of Germany, in the state of North Rhine-Westfalia, it lies rather central, considering Germany’s population distribution. As regulations are passed on a state level, a focus on the most populous state and the most populous city therein, Cologne, provides a good background for studying the research question. Finally, from a cultural perspective, retail Sundays take place in Cologne throughout the year, usually in particular quarters of the city, and the inhabitants in general are rather open to them [

41].

The German shop closing act has remained unchanged between 2018 and 2025 regarding retail Sundays. Only increasing shifts of consumption towards online, mobile, and other digital channels might additionally impact consumer perceptions. Those, however, in many parts are related at least to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The following section introduces the employed methodology and deduces the respective survey instrument. In the third section, the study results are presented and discussed in light of the existing literature and their significance. Based on this analysis, the fourth section concludes, and recommendations for city marketing and management are proposed.

2. Materials and Methods

In contrast to comparable events that usually only take place in a single quarter, on a Sunday in June 2018, the city of Cologne initiated city-wide events across multiple quarters, which coincided with most of the retailers in these quarters being open for business as well. This unique situation offered an ideal environment to collect information on the visitors to these events, i.e., in how far the possibility to go shopping on a Sunday impacted their decision to visit the city of Cologne or the respective quarter. Recently, comparable events primarily took place in a single or two quarters at the same time. From a city marketing point of view, this might be a sensible option, considering the focus of all visitors on single events and quarters as well as a stronger focus on the particular event. Methodologically, the consequence of this decision has been that the study could not be repeated under the same conditions. Thus, a two-stage strategy has been considered to generate a most detailed perspective on post-COVID-19 perceptions. During a comparable event that took place in two quarters of the city of Cologne, by the end of April 2025, data had been collected. Additionally, data had been collected on normal Sundays in quarters across the city of Cologne, which were represented in the 2018 sample. If the two subsamples of 2025 report only marginal differences, it can be assumed that participants’ perceptions of retail Sundays are uniform, and both subsamples can be summarized into a single sample, representing the situation in 2025. While different individual shops might have participated in 2018 and 2025, the opportunity and thus the general situation has been the same in both years.

The survey was carried out by students who were tutored before and during the survey by the authors of the study. All results have continuously been checked for potential biases by the authors. While the quarters where the surveys took place were selected according to the event schedule of retail Sundays, participants were randomly selected. No discrimination regarding gender, age, or origin has occurred. No filtering has been applied, except for the participants having to be fluent enough in German to take part in the survey. Before the interviews, participants were informed about the intentions of the interviews, and their informed consent has been noted. The survey has been approved by the ethics committee of the International School of Management and is listed under code K-2025-JP-12.

The implemented questionnaire can be divided into four parts. Following documentation of the time and location the survey was conducted, socio-economic data is collected. The participants’ previous experience with retail Sundays is queried, since retail Sundays are a rare occurrence across Germany, and it helps in eliciting how far the participants are familiar with the concept. As an introductory question, it also helps participants to shift their attention to this issue. Extrapolating from their experiences, participants’ future outlooks on visiting retail Sundays are used to ease them into the third part, which is about the channels by which they got informed about the retail Sunday taking place and their motivations for visiting the related events or the respective quarter. The survey concludes with a brief outlook on whether the participants expect to be spending additional money in the context of the retail Sunday. This provides a first financial input to city marketing if retail Sunday can provide additional monetary benefits to the participating retailers and event organizers.

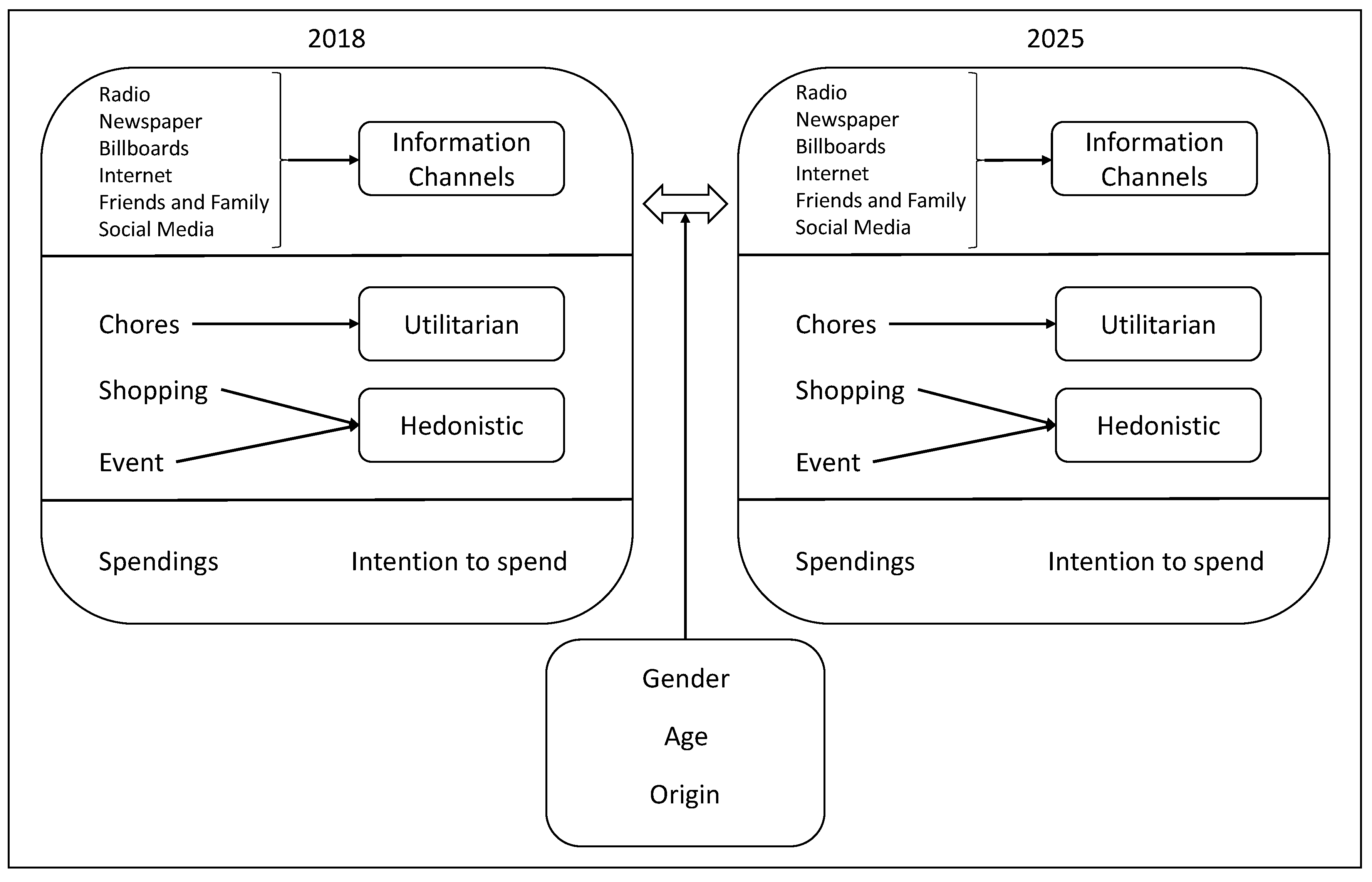

To reduce risks of a common method bias, questions per set, i.e., information channels and motivations, are displayed in random order. Building on the structure of the questionnaire, the overall research design of the study can be summarized in the model illustrated in

Figure 1.

Since the two samples from 2018 and 2025 consist of different participants, all comparisons will employ independent sample tests or multivariate linear regression, even if the main objective of this article is an intertemporal comparison. Since the study takes an exploratory perspective, no distinct research hypotheses are developed. The central research question introduction above can, however, be divided into three partial research questions:

In how far did consumers’ information channels regarding retail Sundays change between 2018 and 2025?

How far did consumers’ utilitarian and hedonistic motivations to attend retail Sundays change between 2018 and 2025?

How far did consumers’ spendings and intention to spend money during a retail Sunday change between 2018 and 2025?

3. Results and Discussion

Data was collected in two waves, in 2018 and in 2025. After data pre-processing, i.e., deleting incomplete or inconsistent observations, for 2018 a total of 993 observations resulted, and for 2025 a total of 158. In the first round the sampling error is 3.17%, and in the second round 7.96%, putting it in both cases below the critical threshold of 10%.

Table 1 summarizes the key sociodemographic characteristics of both samples.

The main difference between the two samples, as illustrated by the table, is that in the recent sample, more inhabitants from Cologne are present. Additionally, those who are not from Cologne traveled a longer distance to get to Cologne. Considering a share of 48.5% males and 51.5% females in the population and an average age of 41.39 years across Cologne citizens [

42], the samples are not perfectly representative, but regarding the distinct share of non-Cologne natives, they can be considered suitably representative for a continuing analysis.

Preliminary analysis, i.e., a Harman single factor test, indicated that no problems with a common method bias exist, neither with regard to the information channels nor with regard to the reasons.

Targeting the first of the three partial research questions,

Table 2 summarizes in relative terms the channels by which participants learn about retail Sundays, either passively or actively searching for information. Asterisks after the different channels indicate the results of Chi Squared-tests, i.e., the respective significance levels. In the further analysis, the following scheme is adopted to indicate significance levels: * indicates significance at the 5% level, ** indicates significance at the 1% level, and *** indicates significance at the 0.1% level.

While the steep increase regarding radio, the weakest channel in 2018, was a surprise, the remaining developments followed predictable patterns. In 2018, there was no question about the relevance of social media. Thus, the distinct drop of other channels as well as the slight decrease in the internet channel might be attributed to participants previously attributing information from social media platforms to these two channels. The results imply that even with an increasing shift towards digital platforms and channels, city marketing is still well advised to propagate news of retail Sundays and related events via a broad mix of platforms.

After the participants have become aware of retail Sundays, the question of particular interest for this study is for which reasons they actually attend those events, i.e., visit the city center or commercial area of the respective quarter? This is the content of the second of the three research questions. To answer this question, participants were given three reasons why they visited the event; for 2025, a fourth reason was added. The reasons, as well as the average scores, based on a four-point Likert scale, are summarized in

Table 3. With the implemented Likert scale, the theoretical average lies at 2.5; values below 2.5 indicate disagreement, and values above indicate agreement. For the first three reasons, a

t-test for independent samples was conducted, and significance results are reported as well as the Cohen’s d statistic. Asterisks indicate the significance level of the conducted

t-test; *** indicates a

p-value of less than 0.001 and if no asterisks are reported, a

p-value larger than 0.05.

The table indicates a general increase in scores regarding all three reasons. However, the change is only significant for the first reason, i.e., in 2025 participants are more interested in shopping than they were in 2018. Comparing the answers for the first and second reasons, in 2018, there is a moderately strong difference that is highly significant (

p < 0.001). This indicates that in 2018, participants were primarily motivated by the events, and the intention to shop was less pronounced. That the COVID-19 crisis leads to a stronger emphasis on utilitarian reasons and less relevance for events can be shown in other contexts like factory outlet centers [

43]. Here, however, the events still play a distinct role in 2025. Thus, the conclusion from these results is that participants do not reduce their hedonistic expectations of an event like this and value the event character similarly as before. The utilitarian expectations, as witnessed by the first two reasons, however, played and still play an equally important role.

The fourth reason that has only been available for the second wave of the survey indicates that structuring the reasons into utilitarian and hedonistic motivators might be too simplistic an approach, and a much more detailed analysis is required. Even though some shops only open on retail Sunday to show presence and be actively seen by visitors, the strong increase in the utilitarian motivation gives a rise that retail Sundays might have a positive financial effect for retailers as well.

To test the robustness of these results for each of the first three motivations, a regression was estimated, with the participants’ evaluation being the dependent variable. The variable year (0 for 2018 and 1 for 2019) gives the independent variable. As control variables, the gender (excluding the single diverse person), the age, and the origin (0 they live in Cologne and 1 they visit from outside Cologne) of the participants are considered. The first row in

Table 4 reports the coefficients of the variables, as well as the significance level, expressed via asterisks. *** indicates a

p-value < 0.001, ** indicates a

p-value < 0.01, and * indicates a

p-value < 0.05. For the R

2, the asterisks express the significance level of the respective F-test. The second row for each variable reports the standard errors. Models I and II consider shopping as the dependent variable, Models III and IV consider doing chores as the dependent variable, and Models V and VI consider events as the dependent variable. The first model in all three cases provides the reference scenario.

The results indicate that the difference, as already witnessed in

Table 3, remains stable across gender, age, and origin as the coefficient remains constant, but for marginal fluctuations. While slight differences according to gender, age, and origin persist, they are mostly insignificant. The only additional insights are that younger people from Cologne are more likely to use retail Sundays for doing their weekly chores. Men from Cologne are more likely to use the day for shopping. Both cases are neither surprising and do indicate utility-oriented motivations. Regarding events as a motivator to visit the city during retail Sundays, no patterns emerge.

The coefficients of determination, at least in the third to sixth models, are very low, and even in the first and second model the effect is of only moderate strength. This is an indicator that the actual motivations of visitors are beyond the differences between 2018 and 2025 and socio-demographics. This result motivates a future, more in-depth study on the actual behavioral motivators in detail and not just their consistency, as has been researched in this study.

To answer the third research question, participants were asked what amount of money they have spent in the context of the current or a typical retail Sunday. To alleviate the cognitive burden for the participants, the answering options are seven groups, from EUR 0 to EUR 201 and above. Consequently, a median amount of EUR 27.24 was spent in 2018, and a median amount of EUR 49.35 was spent in 2025. A U-test underlines the significant difference between these two values (p < 0.001). This result coincides very well with the previous result that the utilitarian motive of shopping became much more relevant for the visitors relative to the hedonistic event motive. The high median for 2025 results in part from the comparatively high share of 30% who spent between EUR 76 and EUR 100 and the 13% that would spend EUR 200 and above. It can be added that it is primarily the participants visiting Cologne that are willing to spend higher sums than the Cologne natives. For Cologne natives, the values only marginally change. Using an ordered probit regression indicates that these results remain stable, if controlling for gender, age, and origin of the participants. Only women are slightly more inclined to spend more money during retail Sundays.

It is also supported by whether participants estimate that in the course of a retail Sunday they would spend more money than on a typical workday. A Chi Squared test revealed that a marginal but significant difference exists between 2018 and 2025 (p = 0.002). The respective cross-table indicates that the share of participants who estimate to spend more has drastically increased in 2025.

Nevertheless, this question comes together with an inherent problem. Currently, retail Sundays are rare events that can emit positive effects regarding customer behavior, and even those effects are comparatively limited. Once they become the norm, the positive monetary effects for retailers might be sustained, and Sundays might become comparable to workdays. For retailers, this would translate into higher expenses while the revenues would be distributed over seven instead of six days. To test the assumption, participants have been asked whether they would visit the respective quarter (where the survey took place) more often, even if no event took place and only stores were open, i.e., the ideal eventless retail Sunday. Creating a cross-table reveals that the participants in 2018 were mostly indifferent regarding this question, while in 2025 there is a strong tendency towards the participants visiting even without events (92.36%). A Chi-squared test shows that this is a moderate but significant change between the years. This coincides again with the increase in the utilitarian motive for visiting retail Sundays. Even accounting for a potential intention–behavior gap, this significant change might provide added incentives to establish retail Sundays in Germany or at least in North Rhine-Westphalia beyond the current four, which are bound to events.

While the preceding discussion broadly followed the idea of a customer journey [

44], the post-purchase and loyalty phase can only partially be translated into the context of retail Sundays. But following up on the previous paragraph, the question can be raised whether retail Sundays can be used to get customers interested in stationary retail again and then get them more strongly involved via local loyalty programs. Thus, the final question asked in how far the participants are interested in local loyalty programs, i.e., a loyalty program focused on the participants shopping in stationary stores of their respective city. The respective question has again been posed as a four-point Likert scale with a theoretical mean of 2.5.

In 2018, the average score was 3.01, which dropped in 2025 to an average value of only 1.9. Thus, from being significantly in favor of this idea (p < 0.001), the participants switched to being significantly opposed to it (p < 0.001), with a significantly strong difference between 2018 and 2025. Together with the results and partial discussion above, the results point towards the following situation: Retail Sundays are events of interest to customers that are useful to selectively raise spending. While opening shops on Sundays might bring more customers into the city center, those participants will still be very skeptical about binding themselves to shopping local. Thus, it remains an open question whether retail Sundays can be useful as a continuous mode of operation. The picture that emerges is rather that of customers that enjoyed the possibility of more days to go shopping, which, however, might not translate into overall more money being spent. Therefore, loyalty programs would provide customers with no directly perceived value.

Comparing these study results with the literature cited above, they in part mirror the results of Grzesiuk [

27], but in an opposite direction. While they would make the situation more convenient for consumers, they would not necessarily offer added benefits for retailers.