Abstract

A lack of access to healthy food has been a problem for low-income residents in many developed urban areas. Due to travel time and additional transportation costs, these residents often opt for unhealthy food rather than nutritious alternatives. This study examines the spatial distribution of food deserts in Mississauga—one of Canada’s most populous cities and a city with one of the highest diabetes rates in the Province of Ontario. Network analysis was employed to map the geographic inaccessibility to essential nutritious food, defined as residential areas that are beyond a 15-min walking distance from grocery stores. Socioeconomic indicators were integrated to identify and compare the regions that are socioeconomically disadvantaged and, therefore, most affected by food inaccessibility. The results reveal the presence of several food deserts spatially dispersed in Mississauga. The implications of these findings are discussed, with a focus on the relationship between food desert locations and the socioeconomic conditions of the affected residents. This study provides a practical, replicable approach for identifying food deserts that can be easily applied in other regions. The model developed offers valuable tools for policymakers and urban planners to address food desert issues, improving access to healthy food and positively impacting the health and well-being of affected populations.

1. Introduction

Access to healthy, affordable food remains a pressing challenge in many urban and suburban settings, particularly for low-income and marginalized communities. The concept of food deserts, which originated in the United Kingdom around the early 1990s, initially emerged from discussions highlighting food scarcity and social exclusion within disadvantaged urban communities, with subsequent research refining criteria for identifying these areas [1,2]. In North America, research has taken into account how racial segregation, income inequality, and car dependency have shaped food landscapes in urban and rural settings [3,4]. Other studies focused on rural communities’ distance to food providers and affordability of food or residents’ perceptions of healthy food availability [5,6]. For residents in low-income neighborhoods, the additional time, cost, and effort required to travel to distant food retailers often results in greater reliance on unhealthy, processed foods [7]. This situation worsens because of the increased cost of living and food insecurity [8], and complications from growing populations in cities with surging demand, bringing about supply–demand questions in urban areas with existing food insecurity.

The disparity in healthy food access has resulted in obesity and other chronic diseases [9,10,11], such as heart attacks, strokes, and high blood pressure [12]. Brownell et al. (2010) [13] states the cause of the United States’ obesity epidemic is more influenced by the lack of healthy, affordable food than personal responsibility. Recent literature reported that full-service food retailers tend to leave areas with low buying power, leaving only small food retailers that provide typically high-priced and low nutritional value options for low-income residents [14,15,16,17].

With increases in both monetary and nonmonetary costs, like commute time to grocery stores, low-income residents often opt for low-cost food with less nutritional value [18]. This is driven by the inconvenience of traveling further to obtain healthy food, coupled with the ease of access to unhealthy options, particularly fast food, leading to decreased consumption of nutritious food and increased reliance on inadequate alternatives [19]. As a result, health issues related to unhealthy eating habits undermine health and well-being, contributing to financial burdens faced by the healthcare system [20,21]. This is concerning for urban centers, as studies in other Canadian cities such as Winnipeg and Manitoba have shown that urban cores are more susceptible to the formation of food deserts than suburban neighborhoods [14]. Thus, it is important to identify and eliminate food deserts to improve social equality and public health.

While the term food desert is widely used in spatial and public health literature, it has been critiqued by food justice activists and scholars for potentially oversimplifying the structural and historical roots of food insecurity. The term food desert implies a passive, natural absence of food, rather than acknowledging systemic disinvestment, racial segregation, and policy-driven inequities [22,23,24]. Although a full exploration of these critiques is beyond this paper’s scope, we acknowledge their importance and use the term cautiously, focusing on the spatial dimension of food access in Mississauga.

There are few studies on food deserts in the Canadian context. Wang et al. (2014) [4] revealed findings specific to community gardens and farmers’ markets in Edmonton, and how they can help to mitigate food deserts. Robitaille and Paquette’s (2020) [25] research highlighted food deserts and the prevalence of food swamps in the Gaspesie region, which appears to be largely rural. Studies in urban cores like Toronto found direct relations between socioeconomic characteristics and spatial profiles of food deserts [26]. Despite these insights, a significant gap remains in food desert research specifically focused on suburban cities like Mississauga, which have distinct socioeconomic characteristics compared to both major cities and smaller rural communities. Mississauga, Peel Region, has one of the highest rates of diabetes in Ontario at nearly 1 in 10 adults, 40% higher than the provincial average. It is reported that 53.6% of residents of the Peel Region are overweight or obese, which is the biggest factor for developing Type 2 diabetes. In addition, past studies have focused on a single socioeconomic variable/index, while this study compared three different indicators: median total income, the Material and Social Deprivation Index (MSDI), and the Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation (CIMD). Different indices have been used in the US context; however, their methods were not transferrable to the Canadian context due to differences in data availability.

This study emphasizes creating an informative and replicable approach to identify food deserts, especially in urban or suburban areas, by combining the spatial aspect of healthy food outlet inaccessibility with the relevant socioeconomic status. Focusing on the geographically inaccessible and socioeconomically deprived areas will provide insights into the presence of food deserts, highlighting their public health significance and promoting discourse in addressing them for the well-being of Mississauga’s citizens.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Mississauga is located on the western shores of Lake Ontario within the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) and Regional Municipality of Peel Region in Canada. Mississauga has a population of 717,961 as of 2021, the seventh largest in Canada and the third largest in Ontario after Toronto and Ottawa. Originally developed as a post-war suburban expansion to Toronto, Mississauga has evolved into a large and diverse city with both suburban and urban characteristics. It houses a large proportion of GTA’s workforce [27] and is a major hub for economic activity.

Neighborhoods in Mississauga vary significantly in terms of built form, demographics, and accessibility. For example, Malton, located in the northeast, is a high density, ethnically diverse area adjacent to Toronto Pearson International Airport, while Port Credit in the south is a historically affluent lakeside community undergoing significant intensification. Other neighborhoods like Streetsville and Erin Mills feature low-rise, residential streets and are less transit-connected. This diversity of neighborhood typologies—ranging from tower-in-the-park high-rises to car-dependent subdivisions—creates distinct accessibility challenges, particularly for lower-income and aging populations.

Mississauga represents a broader pattern of suburbanization seen in North America: sprawling development, automobile dependence, and uneven distribution of essential services like grocery stores [28,29,30]. However, it is also unique due to its size, demographic diversity, and rapidly developing city center. Its infrastructure is still largely auto-oriented, and despite efforts toward transit-oriented development, many neighborhoods remain poorly connected to healthy food options via walkable routes.

In Canada, existing food desert studies have focused on the city of Toronto or GTA [26], grouping Mississauga into broader regional studies, overlooking internal variations. This study closely examines the presence of food deserts within Mississauga and determines whether new conversations about food security in the city are needed. This study contributes a novel case: a large, diverse, suburban Canadian city with both urban and low-density characteristics, analyzed using a GIS-based model that integrates network analysis with three socioeconomic indices. By doing so, it fills a critical gap in the international literature on suburban food access and provides a transferable methodology for use in comparable cities globally.

2.2. Data Sources and Preprocessing

Analysis was carried out at the dissemination area (DA) level, the smallest geographic unit containing detailed Canadian census data. This unit was the preferred level to conduct our study, as attributed socioeconomic indices are also calculated at this level. Past food accessibility studies [26] fused socioeconomic indices such as income and store location data to provide insights into the prominence of food insecurity. The data sources and descriptions of the socioeconomic indices and healthy food providers are provided in Table 1. Geographical boundaries like city boundaries, DA boundaries and residential zones were collected from the City of Mississauga data portal.

Table 1.

Variables, descriptions, and data sources.

Socioeconomic status, including education level, income, and age, is an important consideration when investigating healthy food access, due to possible barriers [31]. Mode of transportation is another factor when gauging travel time. Residents with low income may lack access to cars, taking much longer to reach healthy food outlets through public transportation with additional cost of a round trip.

Lack of healthy food access due to income inequality, considering accessibility, has been a key factor in the analysis of food deserts [3]. Research suggests that the suburbanization of food retailers in North America and the United Kingdom has created food deserts in neighborhoods with relatively low–average income [32]. Income quintiles are often used to measure income-related inequalities, as it can be easily understood by and communicated to non-technical audiences [33,34]. Vanzella-Yang & Veenstra (2021) [35] found that families who spend more time at the bottom quartile of family income in Canada correspond to elevated presence of longstanding illness and/or health problems. Reported studies predominantly applied median total income as a socioeconomic index in analyzing food deserts. This study compares a widely used indicator like income with more nuanced indices (MSDI and CIMD), capturing a larger range of variables to identify regions that may be more deprived and lacking healthy food resources.

MSDI is the most widely used and cited area-based socioeconomic indicator in Canada [36], particularly useful for detecting regions with material and social inequalities in health while also serving as a functional index for historical comparison due to its usage dating back to 1991 [37]. It calculates two dimensions of deprivation: material and social. Relevant variables gathered from Canadian census data utilized towards the calculation of this index, particularly material deprivation, include the proportion of the population aged 15 years and over without a high school diploma or equivalent; the employment to population ratio for the population 15 years and over; the average income of the population aged 15 years and over; the proportion of the population aged 15 and over living alone; the proportion of the population aged 15 and over who are separated, divorced or widowed; and the proportion of single-parent families [38]. These variables are combined using principal component analysis (PCA) to produce a factor score that categorizes each DA into a deprivation quintile [38]. The quintiles range from 1 to 5, where 1 represents the least and 5 represents the most deprived areas. Past studies focused on measuring health outcomes, like one conducted by Tøge & Bell (2016) [39], suggest material deprivation outperforms those focusing solely on income or other socioeconomic status when indicating the presence of poverty, deprivation, and is more strongly associated with health outcomes. Thus, we expect to identify a more refined area using this method and compare any similarities and differences between the most deprived regions.

The CIMD has been referenced in numerous health-related studies, including similar proximity-based studies like the research by Relova et al. (2022) [40], which identified Health Service Areas in communities within British Columbia. Unlike the MSDI’s two dimensions, the CIMD can be differentiated into four distinct dimensions: residential instability, economic dependency, ethno-cultural composition, and situational vulnerability. Economic dependency is identified as the most relevant dimension to the level of transportation access to healthy food locations. The index is calculated with these variables: proportion of the population aged 65 and older, proportion of population in the labor force (aged 15 and older), ratio of employment to population, dependency ratio (population aged 0–14 and aged 65 and older divided by population aged 15–64), and proportion of government population receiving transfer payments [41]. The CIMD is divided into quintiles from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating the least while 5 indicates the most deprived areas. Rent et al. (2017) [42] identified that individuals who have an increased level of economic dependence on others often forego treatment in fear of financial risk, sacrificing their health. The same study found increased financial dependence on others hampered one’s ability to seek healthcare and maintain an adequate quality of life, hurting one’s self esteem, especially when applied to the elderly population. This is highly relevant to Mississauga’s aging population of individuals 55 and over, projected to nearly double by 2028 compared to 2008.

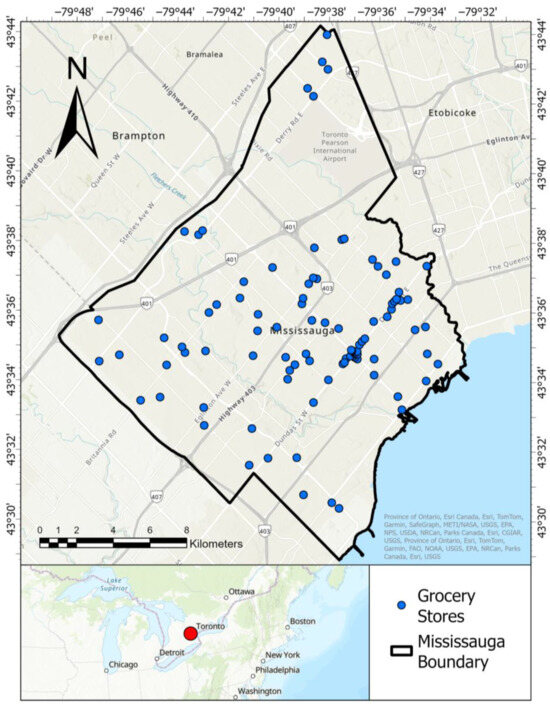

Healthy food locations were extracted from a dataset containing all food outlets in Mississauga, initially derived from the 2021 Mississauga Business Directory, and filtered according to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Specifically, stores classified under 445,110—Supermarkets and other grocery (except convenience) stores (n = 102), 452,910—Warehouse clubs (n = 3), and 452,110—Department stores (n = 11) were included, resulting in a total of 116 potential grocery locations. To prepare for data analysis, data points with missing values were removed from all datasets and non-spatial data were joined with the geographic data. After verification and data cleaning, this yielded the final dataset of 109 locations that offer a variety of fresh food produce and nutritious food options (Figure 1). Convenience stores were excluded, as most of them do not provide fresh produce. Our field visits confirmed that one convenience retail chain does provide fresh produce, but with very limited options and much higher prices compared to supermarkets. We did not include community gardens or farmers’ markets, due to the long duration of winter in Mississauga. Studies show that the presence of a large grocery store in a neighborhood is attributed to more fruit and vegetable servings when compared to regions that lack them [43]. Conversely, increased geographic distance to grocery stores was associated with poor healthy food access [44].

Figure 1.

Location of the study area (red dot)—city of Mississauga, and healthy food locations (blue dots) in Mississauga.

2.3. Identifying Food Desert Areas

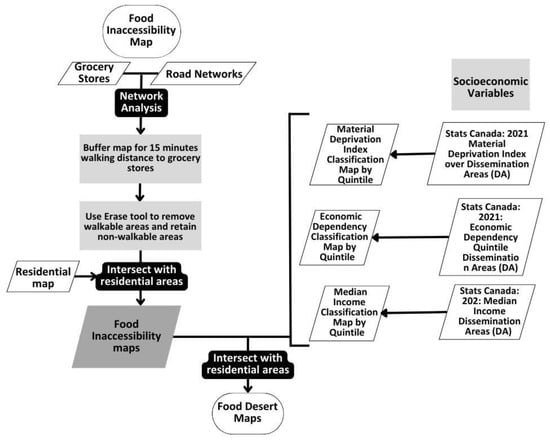

The process for identifying food deserts is illustrated in the method flowchart (Figure 2). It considers the physical inaccessibility for socioeconomically disadvantaged groups.

Figure 2.

Methodology flowchart.

In this study, geographic food deserts (GFDs) are defined as residential areas located beyond a 15-min walk from any healthy food supplier. The 15-min threshold is widely used in public health and planning literature as a proxy for convenient pedestrian accessibility, particularly in urban and suburban contexts [45,46]. This threshold is consistent with standards used in similar studies identifying walkable access to essential services such as food, healthcare, and transit [46,47,48]. While some residents may be able to walk longer distances, the 15-min benchmark reflects a realistic and inclusive standard, especially for vulnerable groups such as seniors, individuals with mobility limitations, or households with young children.

The areas that can be reached by a 15-min walk from or to the grocery stores (Figure S1) were generated through a network analysis in ArcGIS. The input road network data included sidewalks and pedestrian pathways to simulate realistic walking conditions. Although residents could reach these food suppliers through public transportation, the round-trip increases food costs by adding a minimum of CAD 4.25. Driving is another transportation mode residents can use to reach healthy food providers; nevertheless, not all residents can afford a vehicle or are capable of driving. Therefore, this study defined geographic food deserts (GFDs) as residential areas that are beyond 15 min’ walking distance from any healthy food supplier.

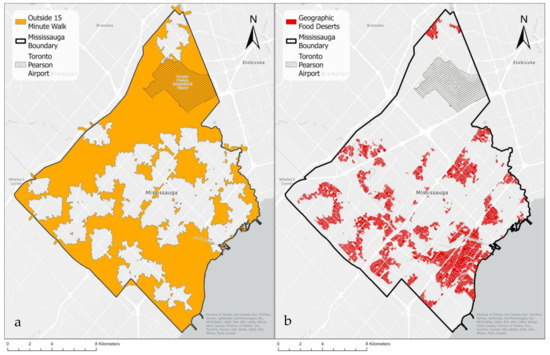

The map showing non-walkable areas (Figure 3a) was created by erasing the above walkable areas from the entire study area. Since such areas include other irrelevant zones, including industrial, commercial, and green space, the map was intersected with residential zones, identified as another end point that residents travel from or to the grocery stores. Figure 3b presents residential areas that are beyond 15 min’ walking distance from healthy food suppliers, defined as GFDs.

Figure 3.

(a) Areas in Mississauga that are not within 15 min’ walking distance from a healthy food location. (b) Geographic Food Deserts (GFDs): Areas in Mississauga that are not within 15 min’ walking distance to a healthy food location intersected with residential regions of the city.

Food deserts are socioeconomically disadvantaged areas within the GFDs that require immediate action to provide alternative healthy food options. Three socioeconomic indicators were considered: the Material and Social Deprivation Index (MSDI), the Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation (CIMD), and median household income. Each variable was classified into quintiles, with the lowest quintile being of particular interest. Income data were further classified into two categories—above and below the median income—providing general context and a broader perspective on economic disparities to highlight areas where households may face difficulty accessing healthy food by highlighting below-median regions.

3. Results

3.1. Food Deserts Based on Geographic Accessibility

Figure 3a shows areas across Mississauga outside a 15-min walking distance to a healthy food location, including residential and non-residential zones, like Toronto Pearson Airport in the northeast. The spatial distribution reveals that large sections of the city, particularly in the north, experience food inaccessibility based solely on geographic distance. Figure 3b focuses on residential areas lacking access to healthy food within 15-min’ walk, highlighting GFDs, concentrated in southwestern Mississauga.

3.2. Socioeconomic Index Maps

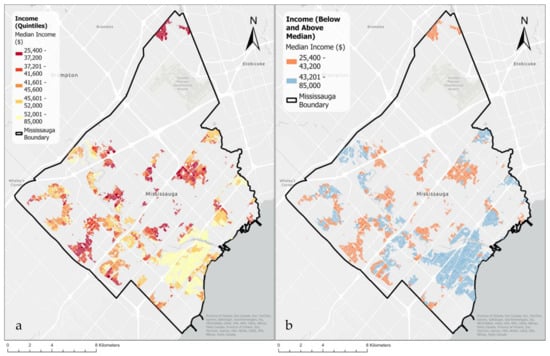

Figure 4a illustrates median income distribution across Mississauga, divided into quintiles ranging from CAD 25,400 to CAD 85,000, with dark red shades representing lower income areas and light yellow shades indicating higher income areas. Most low-income areas are scattered in northern and western portions of the city, whereas notable high-income clusters can be found in southern regions of Mississauga, particularly around neighborhoods like Port Credit.

Figure 4.

(a) Areas in Mississauga not within 15 min’ walking distance to a healthy food location overlayed with median total income. Income data classified into quintiles where regions in the lowest quintile are possible food desert locations. (b) Areas in Mississauga not within 15 min’ walking distance to a healthy food location overlayed with median total income. Income data are classified into two categories: above (represented in blue) and below median (represented in orange) total income.

Dense, low-rise residential communities with little proximity to healthy food options appear as common food desert locations. This can be seen through housing types like in the northern parts of Streetsville (Figure S2) and in western regions of Malton (Figure S3). Overall, the spatial distribution of income is uneven, with a visible income divide between the south and rest of the city.

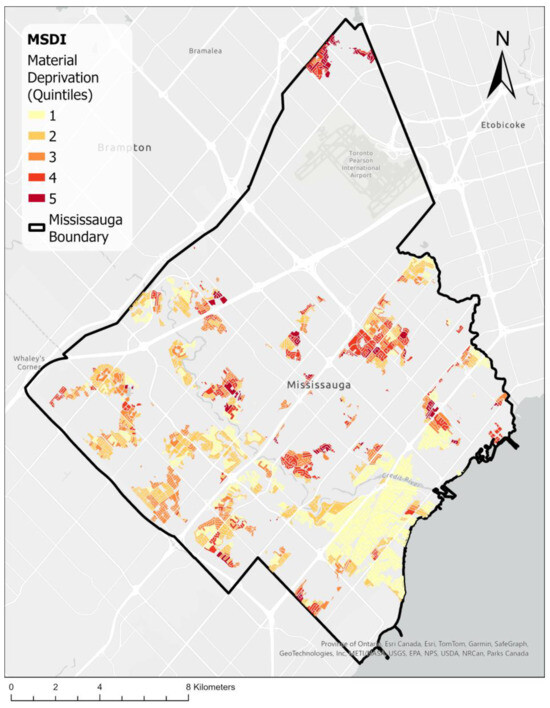

Figure 5 shows a different picture when considering material deprivation at the quintile level from the MSDI index. High deprivation marked by dark red shades indicate areas with significant material resource scarcity. A more scattered result is observed with smaller clusters throughout the city, with highly deprived areas (dark red) predominantly located in the northern and central regions, including parts of Malton and Mississauga Valley. These are residential areas composed of townhouses, semi-detached, and detached housing with little access to healthy food locations nearby. Less deprived areas (light yellow) are more concentrated in the south, west, and southeast, especially around Lorne Park.

Figure 5.

Residential areas in Mississauga that are not within 15 min’ walking distance to a healthy food location overlayed with material deprivation quintiles gathered from the MSDI. MSDI data are classified into quintiles where regions in the lowest quintile are possible food desert locations.

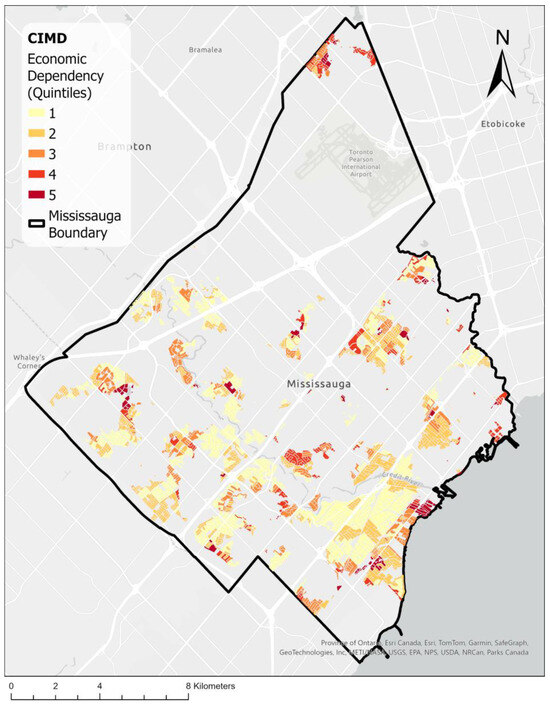

Figure 6 uses the CIMD to highlight economic dependency across Mississauga, with quintiles indicating levels of reliance on social assistance and other economic support programs. High economic dependency (dark red) is evident in the northern regions, particularly in Malton (Figure S4), and sparsely across the central and southern regions. Low economic dependency (light yellow) areas are in the south and southwest, including Port Credit and Erindale. There are fewer areas rendered in a darker tone on this map, as much of the region appears a lighter shade, depicting less deprived areas and contrasting prior mapping methods. Still, the locations isolated in dark red align with prior maps, albeit much more localized. These were found to be mostly higher density complexes, except with one outlier depicted in a pocket near downtown Port Credit to be economically deprived despite being in a more prominently affluent area.

Figure 6.

Residential areas in Mississauga that are not within 15 min’ walking distance to a healthy food location overlayed with economic deprivation quintiles gathered from the CIMD. CIMD data are classified into quintiles where regions in the lowest quintile are possible food desert locations.

3.3. Comparisons of Maps

Comparing Figure 4a and Figure 5, a covariation exists between high MSDI deprivation and low-income areas. In Figure 6, the pattern observed through the CIMD differs from the MSDI and income indices. The CIMD shows a lower severity of deprived areas like Malton and Mississauga Valley (Figure S4), while showing a higher severity in affluent areas like Port Credit. The satellite imagery shows new-build high-density housing in Port Credit and Streetsville (Figure S5).

Table 2 below provides area statistics, both predefined and calculated by means of analysis from our study. Food desert locations were compared in the form of a percentage to the total residential area within the city of Mississauga, as well as to the GFDs identified within the city. When overlaying income data on top of GFD locations under the quintile method, 6.00 km2 were identified as food deserts, approximately 6.4% of all residential areas, and 15.1% of GFDs. This is higher than the results yielded from the MSDI and CIMD approaches.

Table 2.

Statistical results of food desert areas that compare the most deprived areas by index to the total residential area and the residential area outside of 15 min’ walking distance.

4. Discussion

As unhealthy eating contributes to chronic diseases, it is important to provide accessible healthy food options for all residents. Background research on food deserts in Canada within recent years reveals a limited selection of literature, with most studies concentrated in major urban centers such as Toronto [49] and Montreal [50]. This study fills a gap in investigating food deserts in a suburban city such as Mississauga and provides a replicable method to conduct similar analyses in other regions.

4.1. Comparison of Socioeconomic Indicators

Food availability and social status are important determinants of healthy eating in Canada [9]. The role of the physical environment or food availability is most profound in remote or northern communities and has less impact in urban populations [9]. Nevertheless, it disproportionately affects seniors, low-income communities, residents in high population density neighborhoods, or residents without access to cars [4,51]. Social status not only refers to income but also gender, age, and education [9]. Different socioeconomic indices may capture different aspects of social status.

While median income, the MSDI, and the CIMD have been used in separate studies, there has not yet been a study providing a comprehensive comparison of their use in food desert analysis. The MSDI and CIMD capture other dimensions, such as dependency and social isolation, which are not reflected by median income alone and, therefore, complement the income measure [40]. Results show that income captures the highest area of socioeconomically deprived regions for food deserts among the three methods, while the CIMD provided insights that were not captured by median income or the MSDI.

The Median Income approach (Figure 4a) highlights the socioeconomically deprived areas in the city’s northern, central, and western areas. The higher-income regions are in southern areas, such as Lakeview, Lorne Park, and Port Credit. The map identifies areas with dense, low-rise residential settings, which are notably distanced from accessible healthy food sources, as key areas of concern.

The MSDI (Figure 5) effectively captures areas with high material deprivation, highlighting those lacking essential resources and support, which can exacerbate food accessibility issues. It serves as a comparison and secondary opinion on deprived areas by specifically utilizing the material deprivation aspect of the index. By accounting for multiple variables, it better paints a comprehensive image of the variations in socioeconomic status between DAs across Canada. It is of particular importance as per its track record in terms of its validity, reliability, and responsiveness when applied to case studies on public health [52]. It was especially shown to effectively identify variations and connections between numerous health and social issues when properly applied. Its resulting map generally aligns with the one produced using the Median Income approach, but with a more refined area. The income-based method categorizes areas purely based on economic metrics, while the MSDI is a more comprehensive measure that considers not only economic factors but also material deprivation. If resources are limited in establishing alternative healthy food providers, the areas depicted in the MSDI map can be prioritized.

The CIMD (Figure 6) highlights the areas that are not captured by the other two indices, such as in affluent areas like Port Credit. It takes into account dependencies such as age dependency, which was ignored by the other two indices. A wealthy but retired population resides in this area, most of whom may not drive and will need accessible and walkable distances to grocery stores. A closer inspection identifies that the region highlighted in dark red in the CIMD map contains a high-density condominium complex as well as stack townhouses. Such a condominium complex may have limited parking space, signifying a need for walkable distances to grocery stores. Similarly, the CIMD shows higher severity of deprivation in affluent areas like Meadowvale West. In comparison with the MSDI, which captures a broader range of deprivation factors, the CIMD focuses more on economic reliance, which can result in differing classifications of food desert risk areas. As a result, the CIMD map should be combined with the maps from Median Income or the MSDI to paint a broader picture of food deserts.

Compared to other studies that typically paint a few neighborhoods or dissemination areas of concern based on their centroids [4,12,21,26,32], our approach highlights specific residential areas, providing a higher resolution picture for policymakers to make a decision. Robitaille and Paquette developed a method to highlight specific residential areas that are of similar resolution as our approach, but did not take into account of any socioeconomic indicators [25]. Similar to other cities like Saskatoon and Regina that have long and cold winters, in Mississauga, long walking distances between residences and grocery stores create physical barriers for senior populations or those with less mobility [21]. The CIMD outlines areas of concern in affluent neighborhoods due to dependencies. These areas would have been overlooked in other approaches that mostly focus on economic factors. By intersecting the GDFs with different socioeconomic indices, the three maps together tell a story about which low-income residential areas, material-deprived, or high-dependency populations may require interventions.

4.2. Insights into Food Insecurity

As food security is fundamentally intertwined with socioeconomic conditions [53], by identifying regions with limited food accessibility within the most socioeconomically deprived quintile, we sought to identify disproportionately affected areas. The resulting maps reflect a number of food deserts in Mississauga where residents are disadvantaged on a socioeconomic level. Spatially, most food desert areas are scattered throughout the city.

Malton (Figure S6), to the north of a large swath of industrial areas, shows a high-level spatial clustering of food deserts. This is largely due to its proximity to Toronto Pearson International Airport, which complicates access routes for residents. It is surrounded by major highways; therefore, it is not walkable to local supermarkets for healthy food options. This is further fueled by the surrounding industries that promote restaurants, fast food, and other unhealthy food options to serve the needs of the workers in the region who need a quick meal. Malton and other small pockets of food deserts in Erin Mills and Streetsville are towards the boundaries of the city and away from the central areas, which is similar to the findings in Winnipeg or Quebec, Canada [14,25].

Erin Mills (Figure S7) is an area with mixed housing types, such as detached and town homes, with better road networks and public transit access. It has commercial zones dispersed amongst the area, however unevenly, in addition to bordering a highway leading to certain pockets of low accessibility to grocery stores. Streetsville (Figure S8) is a historic community with smaller detached homes and townhouse complexes. The small-scale and pedestrian friendly landscape offers local shopping and dining options but lacks large-scale grocery stores within walking distance for most residents.

By contrast, Mississauga Valley (Figure S9) is located around the center of the city and has relatively good public transit options. However, grocery stores typically exist on the southernmost edges, making it difficult for many residents to access. According to the satellite imagery, Mississauga Valley has dense residential development, including townhouses and condos, as well as detached homes.

As closer proximity to healthy food stores or supermarkets is associated with a higher healthy eating index or alternative healthy eating index, it is important to provide equitable access to healthy food [44]. Our results suggest that residents in Mississauga experience inequitable healthy food access, which may lead to health disparities. The finding is similar to food desert studies in other cities [17,21]. To address these issues, a few strategies may be employed. Richardson et al. [54] reported that introducing a full-service supermarket in a food desert improved residents’ health. Alternative providers, such as community gardens and farmers’ markets, can increase fresh food access and relieve food desert issues [4]. Nevertheless, due to the long and cold winter in Mississauga, these only provide seasonal solutions. Some other studies considered food banks as alternative providers of nutritious food [47]. At the time of field visits in 2021, fresh produce was not observed in the sampled food banks; as a result, they were not included in this study. The situation may have changed post pandemic, especially with an increasing population visiting food banks in recent years. Future studies may explore this option.

4.3. Limitations

There are still limitations in using GIS for food desert analysis [47]. A few limitations are present in this study. Firstly, we only gathered grocery stores within the study area. Due to Mississauga’s proximity to nearby cities and towns, the identified food deserts near the city boundary may be close to other healthy food options in neighboring municipalities. Future studies may gather grocery stores that are outside of but close to the city boundary. Secondly, we only included grocery stores or supermarkets as healthy food providers and excluded other food sources like farmer’s markets or community gardens due to their seasonal availability. With field trip visits to food banks, we confirmed that they either did not offer or had a very limited fresh food selection. As a result, food banks were not included as food sources. The food selection in food banks has begun to change and may change in the future. The field visits to a few convenience store chains confirmed a limited selection of highly priced fresh produce. Further studies can look into the contribution of these food sources in alleviating food insecurity problems. Thirdly, census data comprised 25% sample data self-reported by residents, which may contain inaccurate values. In addition, census data are aggregated and do not represent the individual level. Moreover, census data gathered during the COVID-19 pandemic may have also had a significant role on the calculation of the socioeconomic indicators and income for this study. Other factors may include complications resulting from the extensive construction occurring across the city, which may impact walking times or available routes. Fourthly, we assumed that one store would fulfill all buying needs by shoppers, yet residents typically shop at multiple stores. In future studies, we may consider analyzing distances to multiple stores that offer different selections of food. Fifthly, this study did not consider other transportation means. Some scholars highlighted other important influencing factors, such as the type and freshness of food and the transportation factor [55]. Since our study focused solely on walking distance, other affordable transportation methods such as biking (whether) and/or public transit (cost) were overlooked. Studies have shown that differences in the mode of transportation used can affect accessibility [3,56]. However, limited by the available data and considering the long period of winter in Mississauga, we decided to not further analyze how different modes of transport impact the presence of food deserts. In addition, car ownership data is not available for the study area, making it harder to outline the specific regions that are less reliant on walking. Finally, online grocery store options in the post-COVID-19 pandemic environment may impact residents’ shopping behavior. Nevertheless, we currently do not have accurate data of residents’ preferences, the delivery coverage, as well as the affordability of the added costs. Future studies may incorporate these perspectives when data become available. Lastly, while this study used spatial data to identify food access disparities, we recognize that food insecurity is not solely a function of geographic proximity paired with aggregated social status. Future research could incorporate qualitative data or community engagement to better capture the lived realities and cultural context of food access in Mississauga, in line with critiques from food justice scholars.

5. Conclusions

In Mississauga, about 42.26% of residential areas are beyond a 15-min walking distance to grocery stores. The percentages of residential areas beyond walking distance to grocery stores and with socioeconomically disadvantaged groups are 6.4%, 2.2%, and 1.7%, according to Median Income, the MSDI, and the CIMD, respectively. The visual inspection suggests that the MSDI generally aligns with Median Income when determining the socioeconomically disadvantaged groups that are impacted by food deserts. Nevertheless, the MSDI presents a more refined area—a third of that outlined by the Median Income index. The CIMD captures areas that would have otherwise been overlooked in other indices. Food deserts are scattered throughout the city, with local clustering in Malton and Mississauga Valley. Addressing food accessibility issues provides policy or urban-planning implications for alleviating health disparities. Authorities may consider providing healthy food options in these areas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/urbansci9070265/s1, Figure S1: Areas in Mississauga that are within 15 min walking distance to a healthy food location; Figure S2: (a) Northern Streetsville area low-rise dense housing satellite view. (b) Northern Streetsville area low-rise dense housing in relation to MSDI; Figure S3: (a) Western Malton area low-rise dense housing satellite view. (b) Western Malton area low-rise dense housing in relation to MSDI; Figure S4: Relevant neighbourhoods relative to the City of Mississauga; Figure S5: (a) New build high density housing in Port Credit (b) New build high density housing in Streetsville; Figure S6: Malton area in relation to MSDI. (b) Malton area satellite view; Figure S7: (a) Erin Mills area in relation to MSDI. (b) Erin Mills area satellite view; Figure S8: (a) Streetsville area boundary in relation to MSDI. (b) Streetsville area satellite view; Figure S9: (a) Mississauga Valley area boundary in relation to MSDI. (b) Mississauga Valley area satellite view.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z. and Y.H.; Data curation, H.Z. and L.G.; Formal analysis, T.H., A.W. and L.G.; Funding acquisition, T.Z.; Investigation, T.H. and A.W.; Methodology, T.H. and A.W.; Supervision, T.Z. and Y.H.; Visualization, T.H. and A.W.; Writing—original draft, T.H., A.W. and H.Z.; Writing—review and editing, T.Z. and Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Opportunity Programs, Experiential Education Unit, at the University of Toronto Mississauga.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript or in the supplemental materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Andrew Nicholson for data collection consultations and Moxuan Huang for field visits to food providers. We appreciate Riya Shah’s initial exploration of socioeconomic indices using 2016 census data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cummins, S.; Macintyre, S. A Systematic Study of an Urban Foodscape: The Price and Availability of Food in Greater Glasgow. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 2115–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEntee, J. Highlighting Food Inadequacies: Does the Food Desert Metaphor Help This Cause? Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyer, B.; Voss-Andreae, A. Food Mirages: Geographic and Economic Barriers to Healthful Food Access in Portland, Oregon. Health Place 2013, 24, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Qiu, F.; Swallow, B. Can Community Gardens and Farmers’ Markets Relieve Food Desert Problems? A Study of Edmonton, Canada. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 55, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, C.M.; Nyaradi, A.; Lester, M.; Sauer, K. Understanding Food Security Issues in Remote Western Australian Indigenous Communities. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2014, 25, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro Junior, P.C.; Suéte Matos, Y.A.; de Oliveira, R.T.; Salles-Costa, R.; Ferreira, A.A. Perception of the Food Environment and Food Security Levels of Residents of the City of Rio de Janeiro. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Bulle Bueno, B.; Horn, A.L.; Bell, B.M.; Bahrami, M.; Bozkaya, B.; Pentland, A.; de la Haye, K.; Moro, E. Effect of Mobile Food Environments on Fast Food Visits. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, D. Our Cost-of-Living Crisis: In Just Three Years Rent and Groceries Are up Nearly 40 per Cent—There Are Solutions; Toronto Star: Toronto, ON, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raine, K.D. Determinants of Healthy Eating in Canada: An Overview and Synthesis. Can. J. Public Health/Rev. Can. Sante’e Publique 2005, 96, S8–S14. [Google Scholar]

- Story, M.; Kaphingst, K.M.; Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Glanz, K. Creating Healthy Food and Eating Environments: Policy and Environmental Approaches. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Rennie, D.C.; Dosman, J.A. Changing Prevalence of Obesity in a Rural Community between 1977 and 2003: A Multiple Cross-Sectional Study. Public Health 2009, 123, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Law, J.; Quick, M. Identifying Food Deserts and Swamps Based on Relative Healthy Food Access: A Spatio-Temporal Bayesian Approach. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brownell, K.D.; Kersh, R.; Ludwig, D.S.; Post, R.C.; Puhl, R.M.; Schwartz, M.B.; Willett, W.C. Personal Responsibility and Obesity: A Constructive Approach to A Controversial Issue. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J.; Epp-Koop, S.; Jakilazek, M.; Green, C. Food Deserts in Winnipeg, Canada: A Novel Method for Measuring a Complex and Contested Construct. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2017, 37, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smoyer-Tomic, K.E.; Spence, J.C.; Raine, K.D.; Amrhein, C.; Cameron, N.; Yasenovskiy, V.; Cutumisu, N.; Hemphill, E.; Healy, J. The Association between Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status and Exposure to Supermarkets and Fast Food Outlets. Health Place 2008, 14, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, E.; Raine, K.; Spence, J.C.; Smoyer-Tomic, K.E. Exploring Obesogenic Food Environments in Edmonton, Canada: The Association between Socioeconomic Factors and Fast-Food Outlet Access. Am. J. Health Promot. 2008, 22, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, K.Y.; Tong, D.; Plane, D.A.; Buechler, S. Urban Food Accessibility and Diversity: Exploring the Role of Small Non-Chain Grocers. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 125, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition Quality of Food Purchases Varies by Household Income: The SHoPPER Study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, H.K.; Berkowitz, S.A. Aligning Programs and Policies to Support Food Security and Public Health Goals in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 319–337. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, S.; Macintyre, S. Food Environments and Obesity—Neighbourhood or Nation? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 35, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tao, L.; Qiu, F.; Lu, W. The Role of Socio-Economic Status and Spatial Effects on Fresh Food Access: Two Case Studies in Canada. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 67, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplen, A.K. Julie Guthman: Weighing in: Obesity, Food Justice, and the Limits of Capitalism. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 485–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, J.; Reese, A.M.; Ghosh, D.; Widener, M.J.; Block, D.R. More Than Mapping: Improving Methods for Studying the Geographies of Food Access. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1418–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, K. Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C. Ashante M. Reese. 2019. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Notes, Index, 162 Pages. ISBN: 9781469651491 Paperback. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2022, 44, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robitaille, É.; Paquette, M.-C. Development of a Method to Locate Deserts and Food Swamps Following the Experience of a Region in Quebec, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, E.; Damásio, B.; Bação, F.; Shaker, R.R.; Penfound, E. Urban Habitats and Food Insecurity: Lessons Learned throughout a Pandemic. Habitat Int. 2023, 135, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistic Canada. Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population; Statistic Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021.

- Handy, S. A Cycle of Dependence: Automobiles, Accessibility, and the Evolution of the Transportation and Retail Hierarchies. Berkeley Plan. J. 1993, 8, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. Toronto Megacity: Growth, Planning Institutions, Sustainability. In Megacities: Urban Form, Governance, and Sustainability; Sorensen, A., Okata, J., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; pp. 245–271. ISBN 978-4-431-99267-7. [Google Scholar]

- Filion, P. Enduring Features of the North American Suburb: Built Form, Automobile Orientation, Suburban Culture and Political Mobilization. Urban Plan. 2018, 3, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnik, T.; Tjepkema, M.; Martel, L. Socioeconomic Disparities in Life and Health Expectancy among the Household Population in Canada. Health Rep. 2020, 31, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, K.; Gilliland, J. Mapping the Evolution of “food Deserts” in a Canadian City: Supermarket Accessibility in London, Ontario, 1961–2005. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2008, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichora, E.; Polsky, J.Y.; Catley, C.; Perumal, N.; Jin, J.; Allin, S. Comparing Individual and Area-Based Income Measures: Impact on Analysis of Inequality in Smoking, Obesity, and Diabetes Rates in Canadians 2003–2013. Can. J. Public Health 2018, 109, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S. 63The Quintile Income Statistic and Distributional Analysis. In Markets, Governance, and Institutions in the Process of Economic Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-881255-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vanzella-Yang, A.; Veenstra, G. Family Income and Health in Canada: A Longitudinal Study of Stability and Change. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, M.J.; Wilson, M.G. Rapid Synthesis: Identifying How Area-Based Socio-Economic Indicators Are Measured in Canada. Available online: https://librarysearch.georgebrown.ca/discovery/fulldisplay?vid=01OCLS_BROWN:BROWN&tab=Everything&docid=alma991005118406807310&lang=en&context=L&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&query=sub,exact,Nicu,AND&mode=advanced&offset=10 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Gamache, P.; Simpson, A.; Philibert, D. Validation of a Deprivation Index for Public Health: A Complex Exercise Illustrated by the Quebec Index; Chronic Diseases and Injuries in Canada; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo Da Silva, M.; Gravel, N.; Sylvain-Morneau, J. Material and Social Deprivation Index 2021. Available online: https://canadacommons.ca/artifacts/12251042/material-and-social-deprivation-index-2021/13144894/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Tøge, A.G.; Bell, R. Material Deprivation and Health: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relova, S.; Joffres, Y.; Rasali, D.; Zhang, L.R.; McKee, G.; Janjua, N. British Columbia’s Index of Multiple Deprivation for Community Health Service Areas. Data 2022, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. The Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation, User Guide, 2021. Statistics Canada, 2023. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-20-0001/452000012023002-eng.htm (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Rent, P.D.; Kumar, S.; Dmello, M.K.; Purushotham, J. Psychosocial Status and Economic Dependence for Healthcare and Nonhealthcare among Elderly Population in Rural Coastal Karnataka. J. Mid-Life Health 2017, 8, 174–178. [Google Scholar]

- Zenk, S.N.; Lachance, L.L.; Schulz, A.J.; Mentz, G.; Kannan, S.; Ridella, W. Neighborhood Retail Food Environment and Fruit and Vegetable Intake in a Multiethnic Urban Population. Am. J. Health Promot. 2009, 23, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlala, S.S.; Hill, J.; Kunneke, E.; Lopes, T.; Faber, M. Adult Food Choices in Association with the Local Retail Food Environment and Food Access in Resource-Poor Communities: A Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Diab, E. Understanding the Determinants of X-Minute City Policies: A Review of the North American and Australian Cities’ Planning Documents. J. Urban Mobil. 2023, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosford, K.; Beairsto, J.; Winters, M. Is the 15-Minute City within Reach? Evaluating Walking and Cycling Accessibility to Grocery Stores in Vancouver. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 14, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, L.A.; Sokol, R.L. Measures of the Food Environment: A Systematic Review of the Field, 2007–2015. Health Place 2017, 44, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Higgins, C.D. Travel Behaviour and the 15-Min City: Access Intensity, Sufficiency, and Non-Work Car Use in Toronto. Travel Behav. Soc. 2024, 36, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behjat, A.; Koc, M.; Ostry, A. The Importance of Food Retail Stores in Identifying Food Deserts in Urban Settings. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 170, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Páez, A.; Gertes Mercado, R.; Farber, S.; Morency, C.; Roorda, M. Relative Accessibility Deprivation Indicators for Urban Settings: Definitions and Application to Food Deserts in Montreal. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 1415–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payette, H.; Shatenstein, B. Determinants of Healthy Eating in Community-Dwelling Elderly People. Can. J. Public Health 2005, 96, S30–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampalon, R.; Hamel, D.; Alix, C.; Landry, M. A Strategy and Indicators for Monitoring Social Inequalities in Health in Quebec; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Québec, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leete, L.; Bania, N.; Sparks-Ibanga, A. Congruence and Coverage: Alternative Approaches to Identifying Urban Food Deserts and Food Hinterlands. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2012, 32, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.S.; Ghosh-Dastidar, M.; Beckman, R.; Flórez, K.R.; DeSantis, A.; Collins, R.L.; Dubowitz, T. Can the Introduction of a Full-Service Supermarket in a Food Desert Improve Residents’ Economic Status and Health? Ann. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widener, M.J. Spatial Access to Food: Retiring the Food Desert Metaphor. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 193, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Moudon, A.V.; Ulmer, J.M.; Hurvitz, P.M.; Drewnowski, A. How to Identify Food Deserts: Measuring Physical and Economic Access to Supermarkets in King County, Washington. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, e32–e39. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).