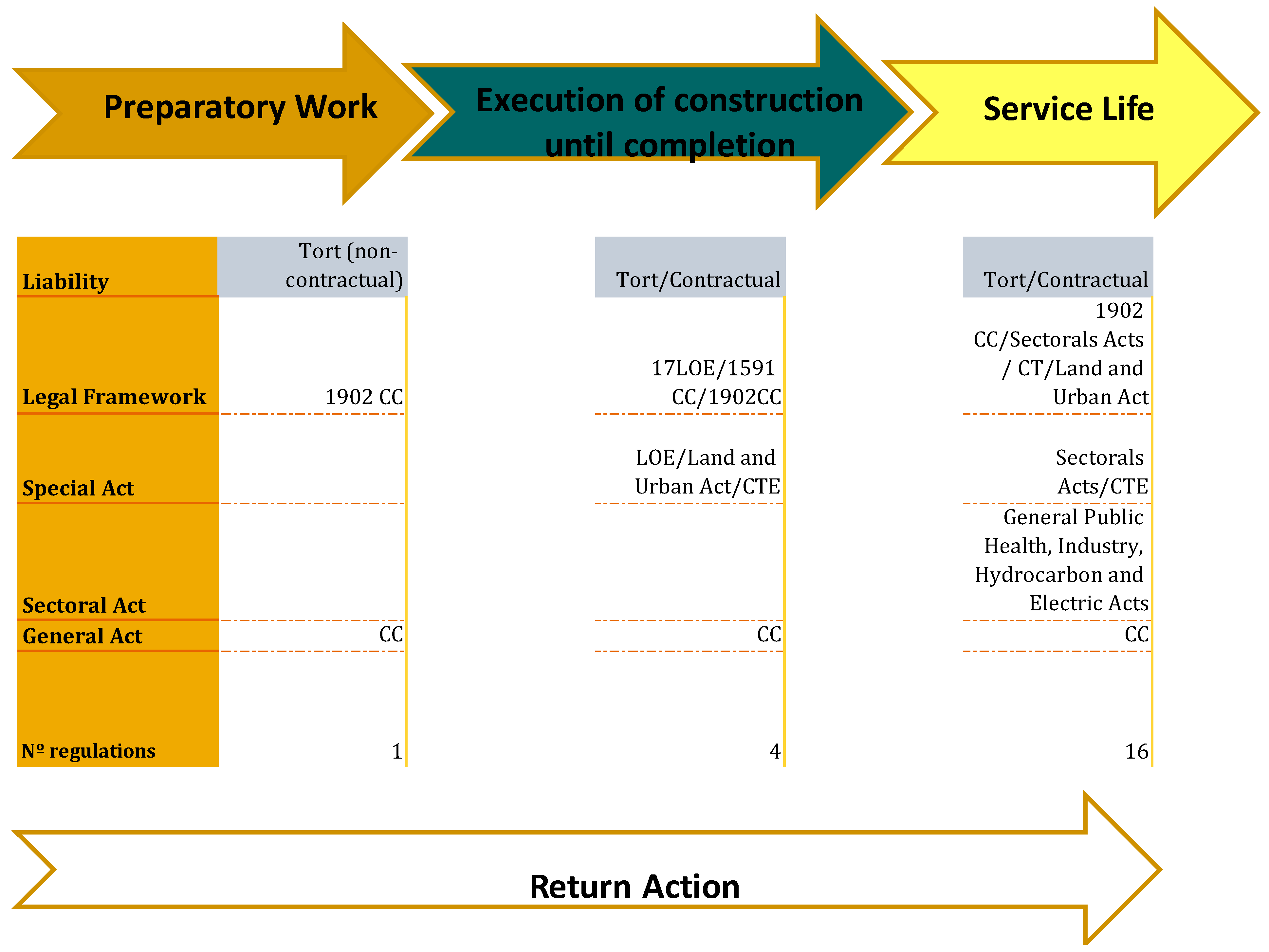

4.2. Responsibilities for the Duty to Maintain and Conserve Installations During Service Life

Installation maintenance and conservation responsibilities are derived from regulatory obligations that are established in specific technical regulations and are developed through regulatory means and complemented by various sectoral norms. This implies not only compliance with legal maintenance but also the performance of work or operations in accordance with applicable legal provisions. This section examines real estate installations from connection through internal distribution. Subsequently, territorial installation responsibilities are examined based on regulations similar to industrial safety regulations. In both cases, liability for damage to third parties is based on Article 1902 of the CC.

Subjective liability serves as a common denominator in real estate installations, from connection to internal distribution.

Determining liability schemes for real estate installations therefore requires analyzing seven regulations and three sectoral acts, as seen in

Table 2. The installations considered are as follows: (1) elevators; (2) low-voltage electrical installation; (3) the prevention and control of legionellosis and indoor air quality; (4) fire detection and extinction; (5) plumbing; (6) sewerage systems; (7) air conditioning and ventilation; and (8) gas thermal installations.

Following the regulatory analysis, the obligations of responsible parties are identified, namely, the maintenance company, the owner, the holder, or the user. The lack of unity (see

Table 3) in the obligations of the responsible parties is justified by the different weights assigned to the potential risks that each one carries, as well as the impact that each risk may have on the health of third parties (such as in the regulations for plumbing, and the prevention and control of legionellosis and indoor air quality).

Among all these types of installations, it is worth highlighting that the responsibility schemes of plumbing installations and those intended for the prevention and control of legionellosis and indoor air quality affect the presence of circulating hot water. These installations have a different framework from the rest. Up to three sectoral acts operate in relation to them, as an accident of this type can affect the health of third-party users. In this context, the party responsible for adequate maintenance is the installation holder, which does not preclude the maintenance company from being subject to compliance with frequencies and inspections. With the new regulation on legionellosis [

54], the possibility of joint liability between the holder and the maintenance company has been introduced. This matter is crucial and represents a change from the previous regulation [

55], in which the holder was solely responsible and could aspire to achivejoint liability only at the discretion of a judge.

In all these installations, liability is subjective (see

Table 4), although there is a quasi-objective application. In this type of liability, the civil claimant must present an expert report that has been prepared by a competent technician, demonstrating that the damage was due to an omission of, defective compliance with, or non-compliance with the duty to maintain.

Therefore, the possible parties and, consequently, the civil defendants responsible for damages caused by installations, from connection to individual distribution, are one of the following: (1) the owner, user, or holder or (2) the maintenance company.

Regarding territorial installations, we focus on two that have regulations that discuss safety in Article 12.5 [

51]. These are high- and medium-voltage electrical networks, and the territorial distribution and storage of gas. The liability framework for these installations is determined, as summarized in

Table 5, based on two special acts; two aectoral Acts; and, for liability enforcement, Article 1902 of the CC.

The scope of these territorial installations extends to their connection with the real estate; however, from that point on, the regulations and liability frameworks change. Thus, regarding territorial installations, liability is presumed to be objective (see

Table 6), in contrast to the subjective framework governing their connection and internal distribution. In both these installations, maintenance is the responsibility of the installation holder, without prejudice to return action against the maintenance company. Additionally, compliance with the prescribed maintenance generates a presumption of legality regarding safety requirements and the consequent determination of liability in the case of an accident.

Consequently, the analysis of sectoral norms allows for an identification of five ways to impute liability to the owner, holder, or user, as well as the different contents of the diligence required of them: (1) liability of the owner or user in the case of elevators; (2) liability of the property in the cases of fire protection; (3) liability of the installation holder in cases of the prevention and control of legionellosis and indoor air quality, plumbing and hot water, sewerage systems, high- and medium-voltage electrical networks, and territorial gas storage; (4) liability of the installation holder or user in the case of air conditioning and ventilation installations and gas thermal installations; and (5) liability of the user in all installations according to the contract with the property and adhering to the use of the installation, without prejudice to its express citation in some installations.

Regarding maintenance companies, which are referred to as “conservators” in some regulations, they have at least the responsibility to execute maintenance under the terms and conditions established in the corresponding sectoral regulations.

4.3. Statutory Contracts: Property and the Facility Manager

This section analyzes statutory contracts commonly employed in real estate sectors to determine the obligations that each entails. While atypical, complex, and mixed contracts operate within this sector, sectional conclusions remain transferable, given that these other contracts rely on general contracting norms, as well as what is regulated for other contracts of a similar nature [

66].

The three statutory contracts we address are service contracts, which imply a mere assignment of means; work contracts, which involve a determined and predefined result; and mandate contracts, through which one person enables another to represent them or carry out specific tasks. The analysis focuses on subject matters linking properties with technical services, such as those that a facility manager can offer.

Work and service contracts are regulated in Articles 1542, 1544, and 1546, Chapter III, Title VI, Book I of the Civil Code [

5] and they relate to obligations and contracts. This general regulation must incorporate the provisions of various special acts such as insurance contracts [

67], urban leases [

13], and the LOE [

4].

A contract for the provision of services—a service contract—regulates the obligation to provide a service or to diligently develop an activity, but without commitment to obtaining a specific result, so that absence is not non-compliance [

68]. This contract is of a principal nature “whose existence does not depend on any other contract, fulfilling its own contractual purpose” [

69].

Among the obligations of the contracting party, the service should be provided while personally ensuring quality or professionalism, including when delegating to assistants under the supervision of the contract [

70]. One of the most relevant obligations of the contractor is to ensure that the service is performed according to the standards and protocols of their profession, observing the applicable conduct guidelines and ethical codes.

Article 1104 II of the CC establishes parameters enabling contractor diligence evaluation, which is limited “to compliance with the rules of art and profession” [

71]. However, some authors, through a complete and joint reading of the article, consider that such compliance must combine the nature of the obligation and the circumstances of the involved persons, time, and place, i.e., the parameters mentioned in Article 1104 I of the CC [

66]. In this sense, diligence not only comprises the efforts of the contracting party but also the ability to foresee potential rational risks and the adopted measures, which, as a corollary, leads us to the behavior of the reasonable person standard in Article 1104 I of the CC.

On the other hand, a work contract, which is not a construction contract, has as its fundamental and differential note that it obliges to a specific result and not to mere activity.

The result can be construction, planning, the provision of services, or an intellectual object [

70]. Thus, the drafting of a project or preparation of an expert report will usually be a work contract [

66], while other professional assignments, such as cost monitoring during the execution of work, can be configured as a service contract [

71].

Contractor obligations include the execution of the activity according to the contract, within the agreed upon terms (Article 1128 of the CC) and following the rules of their profession (Article 1258 of the CC). A lack of professional expertise is “synonymous with guilt” [

71] in the sense of Article 1104 of the CC and, therefore, due to personal, temporal, or local circumstances. Additionally, the contractor is responsible for the people that provide their service.

These two types of statutory contracts allow for the inclusion of penalty clauses for contract breaches, such as delays in installation maintenance execution. They may also incorporate indemnification obligations to the property owner in case of damages, for example through insurance subscription. These measures seek to incentivize contract compliance while restoring the property’s financial balance. However, civil liability continues to fall on the property owner, along with the consequent reputational damage.

The third statutory contract we analyze is the mandate contract, which is regulated by Article 1907 of the CC and obliges a person to provide a service or perform a task on behalf of another.

Among the obligations of a mandatary contract, we highlight [

71] the following: (1) to respond to the damages and losses caused, whether by non-execution or non-compliance and whether by intent or fault; (2) to execute the mandate according to the instructions of the principal or, failing that, according to the sector’s uses ( in any case, they will act in good faith and in the interest of the principal); (3) to render accounts and inform someone of their operations, unless otherwise agreed upon.

The mandate can be simple or representative. In a simple mandate, the obligations and possible actions are between the third party and the mandatary (Article 1717 of the CC), unless it concerns the principal’s own matters (Article 1717 II of the CC). In the representative mandate, the linkage of claims is between the principal and the third party [

68].

In the real estate sector, a mandate contract is usually accompanied by voluntary representation. Representation is the means or instrument by which an assignment is fulfilled, enabling the representative to act before third parties. A mandate can be tacit or express. The key difference between a mandate and representation is that the mandate is exhausted in internal relations between the parties, while representation “attributes to the third party the power to issue a declaration of will before third parties in the name of the principal” [

71].

Representation can be direct, that is, in the name of another, contemplatio domini, which implies that the action directly affects the represented party. Thus, the third party takes direct action against the represented party, who must assume the obligations incurred by and within the limits of the mandate. In this case, the representative must clearly identify whom they represent, and the third party must accept this representation.

However, representation can also be in the name of another (i.e., indirect or mediate representation), in which case the name of the represented party is not disclosed and the third party takes actions against the representative, without prejudice to the repetition that may exist for the obligations incurred by the representative.

Therefore, contractual relationships between properties and facility managers help delimit the respective obligations and non-contractual liabilities, as well as the scope, for both parties.

4.4. Responsible Parties and Liability Schemes for the Duty to Conserve and Maintain

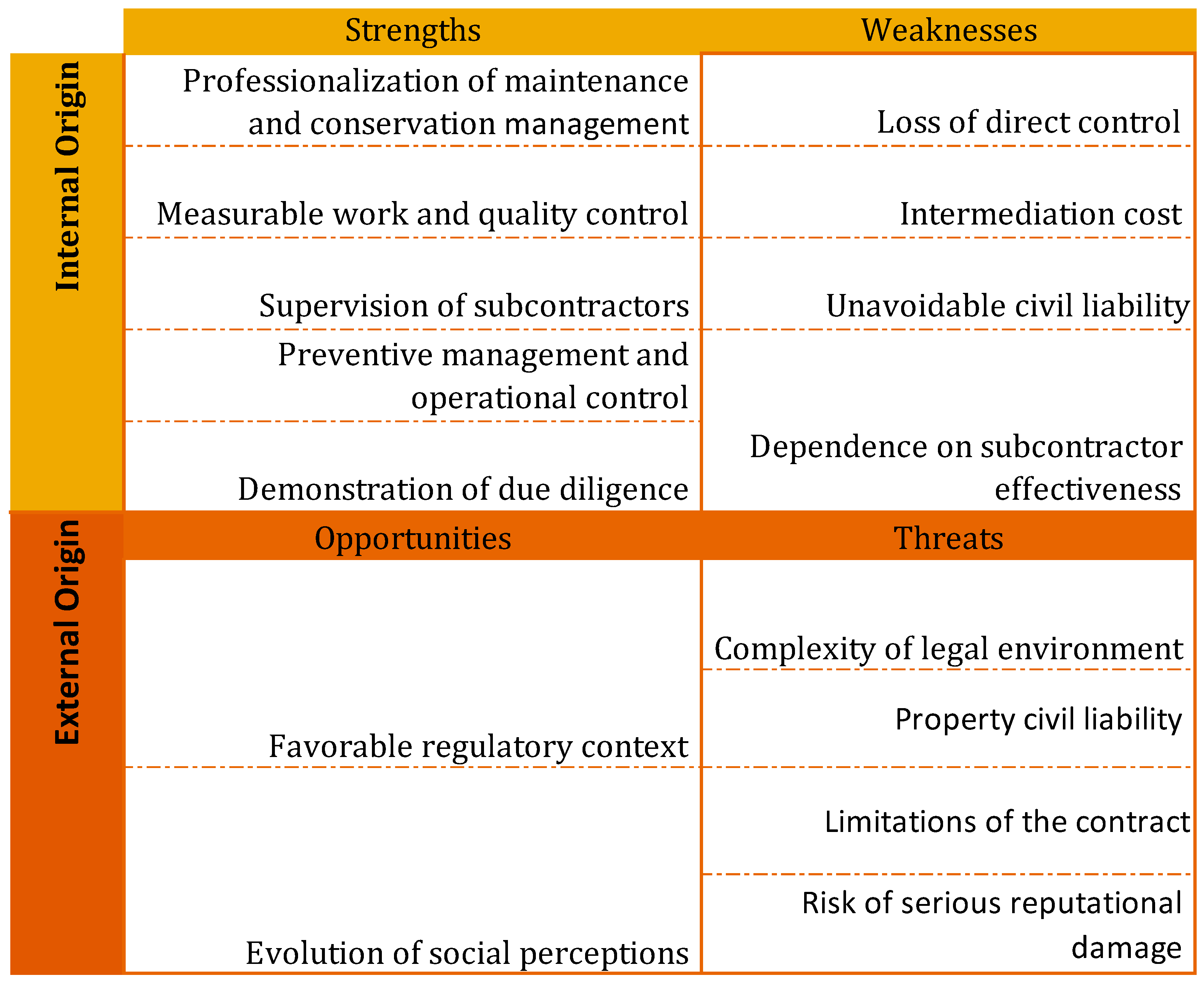

During real estate service life, properties face various responsibilities derived from conservation and maintenance obligations, and property may face various responsabilities that are derived form the obligations of the duties to conserve and maintain real estate. The efficient management of these obligations not only guarantees the conservation and maintenance of assets but also guarantees the maintenance of investment. To minimize reputational damage derived from third-party damages, this study proposes transferring the responsibility to an FM, which requires a proper contractual articulation between the parties.

As discussed in the previous section, no single liability scheme exists for tort liability due to omission of, defective compliance with, or non-compliance with conservation and maintenance duties. All examined schemes incorporate third-party risk weighting, as well as the determination of who benefits the most from the use of the real estate to attribute liability.

The current Prevention and Control of Legionellosis Act [

54] groups the analyzed schemes into four liability attribution blocks according to the cause of damage: (1) quasi-objective imputability of the owner and possible user liability; (2) liability of the maintenance company and diligence of the owner; (3) imputability of the maintenance company with liability of the installation holder or user; and (4) full imputability of the installation holder.

The first block applies to constructive conservation, while the remaining blocks affect installation maintenance and conservation. In the first block of liability for constructive conservation, there is a quasi-objective liability in the subjective scope of the owner. In the second block, which is related to the maintenance of installations, liability falls directly onto the maintenance company and applies to sanitation installations. In the third block, maintenance companies are responsible for executing maintenance, but the installation holder must verify its proper functioning and comply with obligations derived from any detected risks or defects, which, in turn, translates into authorizations that must be issued by the owner or holder. This third block operates in installations such as elevators, low-voltage electrical networks, legionellosis, fire protection, air conditioning and ventilation, gas thermal installations in buildings, plumbing installations, and hot water.

The fourth block of liability deserves special attention as it involves objective risk liability. This type of liability falls onto those who obtain economic benefit from the existence of risk unless they prove that the damage did not arise from the source of the risk. It applies to territorial distributions, and the storage and connection of gas and electricity to real estate. This liability model applies to “social and economic activities…of a professional nature whose risk is likely to yield benefits for the holder,” as stated by Professor Reglero [

72], and was directed at business and manufacturing activities in the 19th century based on the idea that “those who create risk must respond to consequences…” [

73].

After analyzing

Section 2.1 and

Section 2.2, as well as what is discussed in this section, owners, installation holders, or users are concluded to be responsible in the case of tort caused by omission of, non-compliance with, or defective compliance with conservation or maintenance duties for real estate or its installations. This liability operates regardless of the urban status of the land, compliance with planning parameters of the real estate, the legality of use, or the completion state of the property.

Additionally, when the property, owner, or user of the real estate are not the same person and thus are established by the regulatory norm of that installation, the property must prove compliance with certain diligence parameters. These serve to determine whether the behavior has been appropriate.

Table 7 summarizes the liability schemes from the exclusive perspectives of the owner, holder, and user, differentiating whether it affects responsibility or diligence.

Therefore, the property assumes a responsibility that, depending on the cause of the damage, can concretely be a personal responsibility or, at least, will comply with certain diligence parameters.

4.5. Facility Managers and Their Contractual Relationships with the Property

FMs’ functions encompass broad responsabilities aimed at achieving property objetives, with consequent value generation. This involves not only ensuring the operation of the real estate but also addressing other issues such as occupant well-being, spatial optimization, or sustainability implementation. FMs’ functions accommodate expansive interpretation, extending to urban-scale development.

Classic FM functions include supervising and contracting resources that are essential to ensure compliance for both constructive elements and installations linked to the real estate (see

Section 2.1 and

Section 2.2). These functions are carried out on behalf of the property or its representative and are usually articulated through a statutory service contract.

This type of contractual relationship entails two relevant consequences for the property in case of an accident, which are—(1) property responsibility, coupled with proving diligence, implying compliance with lex artis ad hoc and the suitability of the contracted company for work execution, and (2) potential reputational damage for property owners.

To examine these issues, other contractual modalities need to be explored within the statutory contracts discussed in

Section 2.3 that would be suitable for transferring responsibility from the property to an FM, thus minimizing reputational damage risk.

A possible solution lies in employing a statutory work contract rather than a service contract. Thus, within its scope will be compliance with all duties linked to conserving and maintaining the real estate. This shifts from a means assignment contract focused on task performance to a result-based contract. With this change, return action will require contractual liability from the FM.

However, this alone does not meet the study objective since its effectiveness focuses on return action and not on third-party tort liability. At this point, a mandate and representation become crucial.

Section 2.3 demonstrates that effective responsibility transfer from owners to FMs requires representative mandates so that tort actions are present between the FM and the third party. Likewise, relationships involving the issuing of a declaration of will (e.g., requesting installation registration in official records) should be carried out by the FM through indirect or mediate representation power. In this way, claims are directed against the FM without compromising the property name.

Given the regulatory dispersion of the matter, the content of the contractual relationship between an FM and a property need to be more precisely defined. As analyzed in

Section 2.2, the responsibility derived from the maintenance and conservation of the real estate may fall on the owner, holder, or user. However, as summarized in

Table 7, the owner must always prove a certain standard of diligence.

Thus, to achieve the objective of this study, we must determine who the installation holder is. From a legal perspective, the holder serves the installation. However, this definition is insufficient in the technical scope of installations, as the holder is the one registered in the corresponding administrative records as being responsible for the proper functioning of the installation; they also have the decision-making capacity to assume authorizations, prohibitions, or maneuvers. Therefore, the holder’s responsibility is not limited to maintenance but also involves due behavior in risk situations.

“Holder” is a broader term than “user”, whose liability is limited to proper use. Thus, the installation holder approaches the fullness of the owner’s faculties without affecting the legal title.

Therefore, to achieve the effective transfer of responsibility, the ownership of installations needs to be changed in favor of the FM. In this way, when the sectoral norm determines the holder’s responsibility, it falls on the FM, and when the property must prove diligence, the FM will prove it. Consequently, possible repercussions for the scope of tort responsibility cease to be present for the property, as the FM assumes them.

Therefore, changing the ownership of the property or holder is not only appropriate but necessary to achieve the effective transfer of tort responsibility in favor of the FM, except for in relation to fire protection installations. In these installations, express mandate formalization is required for the FM to act as the property responsible for operations.

Consequently, a regulatory analysis allows us to offer solutions in relation to new demands [

37], and, after studying the installations referenced in this article, the combined use of certain statutory contracts is concluded to change the ownership of installations in favor of the FM.