Abstract

(1) Background: Older people ageing in place alone with functional limitations experience several difficulties in daily life, potentially hampering their social participation. This in turn could impact their perceived loneliness. This paper aims to investigate these issues based on findings from the IN-AGE (“Inclusive ageing in place”) study carried out in 2019 in Italy. (2) Methods: The focus of this paper is on the Marche region (Central Italy), where 40 qualitative/semi-structured interviews with seniors were administered in both urban and rural sites. A content analysis was carried out, in addition to some quantification of statements. (3) Results: Older people are mainly involved in receiving/making visits, lunches/dinners with family members and friends, religious functions, walking, and watching television (TV). Overall, the more active seniors are those living in rural sites, with lower physical impairments, and with lower perceived loneliness, even though in some cases, a reverse pattern emerged. The results also indicate some different nuances regarding urban and rural sites. (4) Conclusions: Despite the fact that this exploratory study did not have a representative sample of the target population, and that only general considerations can be drawn from results, these findings can offer some insights to policymakers who aim to develop adequate interventions supporting the social participation of older people with functional limitations ageing in place alone. This can also potentially reduce the perceived loneliness, while taking into consideration the urban–rural context.

1. Introduction

According to a great part of the literature, it is difficult to find a clear and univocal/standardised definition and assessment/measurement of social participation, especially with regard to older people. Several taxonomies, more or less comprehensive, and including a wide understanding of social–community involvement/interactions, as well as of social life, civic engagement/connectedness/integration, do exist [1,2,3,4], referring to varying experiences of social participation, and influenced by both individual and structural factors [5,6]. Similarly, studies on later-life social exclusion [7] are not well developed, especially with regard to the domain of civic participation, which overall remains less explored in the literature [7,8]. Social participation is thus a broad umbrella concept assuming several forms for people involved in community life, including social–leisure activities, which can be cultural, political, volunteer-based, and much more [9,10]. Some authors distinguish leisure activities (e.g., sports, games, arts, hobbies, travelling/tourism), from social activities (e.g., contacts with family members/others, participating in social/cultural events, political parties, volunteering) [11]. However, leisure and social terms, when referred to social participation, remain strictly connected, since both imply social interactions, and represent key aspects of wellbeing [12]. This reveals the multidimensionality of both social exclusion and social participation, which has a great impact on several domains in the course of life and is strictly linked to the vulnerabilities often affecting older people [7].

Generally, social participation is “a person’s involvement in activities that provide interaction with others in society or the community” [1] (p. 2148). However, both collective/societal level and individual/personal activities, e.g., reading and watching television (TV), can be considered [6,13,14], since different levels of individual proximity/involvement with other persons are possible, e.g., even alone or with others, in parallel or with interaction [1,15]. Other authors [16] define both inward-looking and outward-looking patterns for social participation, respectively, person-centred and focusing on one’s values, and performed to create relations/connections with other persons. It is also worthy to consider that different existing definitions of both social participation and exclusion in old age can also present overlapping across their elements [7].

Following the rapid and increasing process of population ageing that poses many challenges in all countries concerning overall welfare and health systems and the quality of life of older people, social participation can represent an important issue that can greatly impact these aspects [17]. In addition to several factors, e.g., socio-demographic and available care arrangements, which crucially impact the possibility of ageing in place [18], social participation can improve everyday life for older people, thus contributing to the perception of environments in a more age-friendly manner [19]. Ageing in place, i.e., to continue to live in one’s own home rather than elsewhere (e.g., a residential care facility), implies providing older people with services, allowing them to maintain as much as possible their residual autonomy/functions, including social engagement and networks [20]. Moreover, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [21] indicates that psycho-physical state, personal conditions (e.g., socio-economic status), daily activities, environment, and social interactions and participation are among the main components impacting overall health of the individuals.

Social participation can also mitigate the perceived loneliness of older people, especially when ageing alone in place/their own home. Loneliness represents a subjective perception/feeling of being alone/neglected, of lacking meaningful relations with others, e.g., family members and friends, with a discrepancy between actual/available and desired relations/contacts [22,23]. Loneliness is also associated with a greater risk of depression and functional decline [24]. Depression represents a mental disorder particularly common in seniors, and perceived loneliness greatly affects and even predicts geriatric depression, with consequent physiological disease and even mortality [25,26,27]. Thus, several seniors experience both loneliness and depression, also following the loss of close relatives and reduced community activities [28]. Social participation can combat loneliness and depression by enabling positive social/emotional spheres and overall relationships for seniors [29].

Social contacts with other persons both in the home and in the community can also positively impact the functional status/health of frail seniors [30,31]. Frailty in particular represents a multidomain condition often following the overall ageing process, as increasing physical and cognitive limitations affect the possibility to perform both the basic and instrumental daily life activities autonomously (respectively, ADL—Activities of Daily Living, and IADL—Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) [32], with the necessity of help and support [33]. In this respect, some authors [34] observed that the overall increased social participation of older people, and in particular higher levels of integrated/diverse social–leisure activities, were associated with a lower likelihood of being in higher/worse levels of frailty, with a related delay and prevention of frailty progression. Thus, both the frequency and diversity/types of such activities could have beneficial effects throughout the course of life, including later life. Other authors [35,36] support the positive link between greater social–leisure activities and a lower risk of frailty. Chang et al. [37] also found that good social relationships were positively related to the greater involvement of seniors in social–leisure activities, and this in turn was associated with their better health. In this respect, it is worthy to mention “The Activity Theory of Ageing” [38], which argues how maintaining active social interactions can lead to better ageing and quality of life. The social participation of older people is indeed included among several aspects (individual, social, structural) defining the active ageing concept, which also involves the quality of life and mental/physical wellbeing [39]. Studies in the previous literature found that social capital and social relationships positively affect the subjective wellbeing of older people, especially those with chronic diseases and disabilities, as overall positive feelings also combat the presence of depression [40,41,42]. In particular, social support/capital and social participation can improve the wellbeing of seniors living alone [43], with community social capital and cohesion positively influencing independent living [44]. Social resources and social support can indeed reduce unhealthy behaviours (e.g., refusing medical help) which are linked to low health outcomes [45]. Social participation is also considered as a third pillar, in addition to health and security, of the active ageing model highlighted by the World Health Organisation [46]. Moreover, both mental and physical social–leisure activities might mitigate the negative effect of loneliness on cognitive functions of seniors [47]. Thus, conversely, poor/lacking social relationships of older people could negatively affect functional limitations and activities of daily living, with overall physical decline and poor health outcomes, including geriatric depressive symptoms [45,48]. Also, the link between multimorbidity and functional limitations could be increased by a low level of social participation [49]

However, a reverse pattern has to be considered, i.e., frailty and functional limitations can hamper seniors’ possibility to participate to social life, thus acting as obstacles for their social interactions and opportunities, with a consequent potential loneliness and low quality of life [29]. Some authors also linked higher physical pain/complaints and worse cognitive function to lower social participation [50]. In particular, Hanlon et al. [51] found that frailty in older people was associated with “social vulnerability”, as poor/inadequate social interactions/support and social isolation. Moreover, especially for seniors with functional limitations, possible barriers in the external environment (e.g., broken streets and sidewalks) can reduce their mobility and possibility to make external social activities and maintain social relations, this in turn potentially leading to loneliness [52]. Elmose-Østerlund et al. [53] found that both physical and psychological conditions greatly impact the possibility for physical activity participation, and this increases with age. Other authors highlighted a positive link between loneliness and ageing, due to scarce social contacts in old age, also following the death of peers and increasing physical limitations [54]. In addition, a low available income might also inhibit seniors from participating to social activities [55].

Both definitions and factors related to social participation may differ across countries, within a country, across neighbourhood environments [3]. Diverse cultural, political, economic, social, and community contexts can thus impact social participation [1]. The physical, social, and economic characteristics and disparities of the urban and rural spaces differently affect the possibility of seniors autonomously performing both activities of daily life and social participation. In rural areas, essential social–health services are less available/accessible, especially for older people, and overall, an increasing depopulation and geographical isolation emerge, which in turn could also hamper social activities. In particular, in rural areas, there is often a lack of adequate public transport services with a consequent low external mobility, especially when this hinders access to external built environment to seniors with functional limitations or disabilities [56]. Other authors highlight some characteristics of rural sites (e.g., natural/territorial assets, economic structure, services availability) as impacting on rural age-related exclusion [7,57]. In urban sites, more services and opportunities of social interaction are available, even though external social participation could be limited due to a neighbourhood that is perceived as unsure [29,58]. Previous research has shown that the social participation of older people living in an urban environment was associated with their higher presence, or even perception, of available and accessible services/resources for them [59]. More recent studies [2] found a greater mobility and less social deprivation in some urban areas, with these being associated with the greater social participation of seniors. More generally, Vogelsang [60] found that older residents in rural counties were less socially active than those living in “more-urban” counties.

In Italy, i.e., the country where this study has been carried out, as of 1 January 2025, people aged 65 years and over constitute 24.7% of the total population [61], representing the highest value in the European Union (average: 21.3%). Moreover, across Europe, the median age is highest in Italy (48.4 years) and lowest in Cyprus (38.4 years), confirming the relatively old Italian population structure [62]. Also in Europe, the prevalence of frailty among seniors aged 65 years and over is 12.3%, with higher values in the south (16% in Italy) and lower in the north (6% in Sweden) [63]. In particular, in Italy, 48% of seniors have difficulties in performing ADLs and IADLs [64]. In the Marche region (Central Italy), where both urban and rural sites were selected for the interviews, as of 1 January 2025, people aged 65 years and over constitute 26.6% of the population [61], which is above the country’s average. Also, 42% of them report severe difficulties in performing personal care and household activities, thus belonging to one of the regions (especially in the South) with major disadvantages in this respect [65]. All these circumstances are even more crucial for seniors living alone. In Europe, these are 20% men and 40% women, and, respectively, 18% and 38% in Italy [66].

The social participation of seniors in Italy (especially recreational, cultural, and civic activities and of a sporting nature) is lower than the total population average, even though it is better for people aged 65–74 [67]. Some authors also indicate that in Italy (and Spain), seniors socially participate less than in other European countries, with a drop beginning from 60 years of age, whereas in Europe the average for this decrease is 70 years [68]. In particular, considering the European average, 45% of seniors aged 65–74 years, and 34% of those aged 75 years and over, spend at least three hours per week performing physical activity. In Italy, the same values are 34% and 22%. Moreover, respectively, 55% and 35% participate in cultural and/or sporting events (32% and 12% in Italy), whereas 4% and 3% perform artistic activities (0.7% and 0.5% in Italy). Also, on average, 49% of European seniors aged 65 years and over report tourism activity (29% in Italy), and reasons for not travelling are mainly due to bad health conditions. Overall, the decreasing social participation of the oldest people reflects increasing levels of disease and frailty among seniors [66]. With regard to social participation in the Marche region, few data are available to date. However, a source [29] indicates a low overall level of engagement of seniors in this respect, and a greater attendance at places of association, mainly churches and parishes.

For frail older people living alone in place, available supports are crucial, for both carrying out ADL and IADL, and also for social participation. In this respect, formal/institutional care prevails in northern Europe, whereas informal/family care predominates in southern Europe, e.g., in Italy, where 50% of seniors receive help from their relatives (mainly from their children), and only 17% from home care workers (HCWs) and personal/private care assistants (PCAs), and a lesser 7% from friends/neighbours/volunteers [69,70,71].

Following the above considerations, this study proposes some results which emerged from the “Inclusive Ageing in Place” (IN-AGE) research project [70], with regard to the Marche region as representative of Central Italy, as better described in Section 2 on Methods. This study explores how frail older people ageing alone in place perform their social participation in both urban and rural sites. For this aim, the following research questions are formulated: (1) Which social–leisure activities are still carried out by frail older people living in urban and rural sites in the Marche region? (2) Which social–leisure activities are no longer practised? (3) Is the level of functional limitations associated with the overall social participation of these seniors? (4) Is the level of perceived loneliness limitations associated with the overall social participation of these older people? It is hypothesised that some activities, mainly those implying moving outdoors, are less frequent for seniors with functional/mobility limitations, especially when external built environments are not very accessible, with possibly fewer opportunities of social interactions in rural areas, due to a greater scarcity of available services in these contexts. Also, reduced social participation could be associated with the greater perceived loneliness of these seniors.

With this paper, we fill the knowledge gap of current few/lacking information/data on the social participation of frail older people at the regional and urban–rural level in Italy. The results of this study, including a simplified classification/operationalisation of social–leisure activities (based on the previous literature and on narratives), might help researchers, healthcare professionals, social workers, and policymakers to better understand some peculiarities of each activity. In addition, this study could provide evidence-based information, including potential urban–rural disparities, for developing appropriate services/interventions and informing strategies targeting local environments, to enhance the social participation and cohesion of seniors, especially those ageing alone in place, to in turn reduce loneliness and preventing late-life depression, thus improving health outcomes of older people in both urban and rural sites [50].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Sites, and Participants

2.1.1. Study Design

“IN-AGE” is a qualitative study carried out in May–December 2019 in three Italian regions: Lombardy in the north, Marche in the centre, and Calabria in the south. It involved 120 older people aged 65 years and over, living in three medium-sized urban sites (about 100,000–200,000 total residents) [61] and three rural/inner areas (both one for each region). About 58% of Italy is covered by the latter, where the most peripheral municipalities are located, and where 23% of the population resides. In Central Italy, the relative weight of these areas is 55%, and it is 46% in the Marche region [72]. Forty interviews were realised in each region, including twenty-four in urban sites and sixteen in rural zones. As for the socio-economic development level of the country, these three regions represent respective different parts of Italy, including available support services for frail older people, i.e., higher in the north, medium in the centre, and lower in the south [73]. In particular, vertical/regional differentiations characterise Italy, with deep structural and economic disparities among macro-areas, especially between the north and south, with greater advantages in the former as for gross domestic product (GDP), employment, productivity, social capital, local policies, and overall highest living standards. For instance, in 2018, the GDP per capita in the south was at 55% of the centre–north, and the unemployment rate was, respectively, around 18% vs. 11%. In southern regions, there are thus lower employment opportunities, with consequent migration and demographic decline, and a lack of policies to support a more adequate development. Central Italy represents the “bridge” between the north and south, with moderate living standards, but economic development and available income remain below the national average [74]. These social-economic contexts are reflected in different/regional welfare systems, and impact the development and provision of health–social services, as follows: more generous and integrated public–private healthcare in the north, e.g., Lombardy, with innovative social policies and developed services for older people; mixed but not fully integrated service provisions in the centre, e.g., in Marche, however with a good implementation of supportive policies and practices; and lower care opportunities in the south, e.g., in Calabria, with a minimal and problematic welfare system [75,76]. With particular regard to support services for older people, some findings confirm a strong regional differentiation, especially regarding the availability of public services, which are provided more in the north and in the centre, whereas monetary transfers prevail in the south (e.g., 18% in the Calabria region, vs. 10% in the Lombardy/north and 13% in Marche/centre), where these transfers are mainly used to hire PCAs [77]. Moreover, according to further data for 2021 [78], the per capita expenditure of the municipalities for services dedicated to seniors aged 65 and over is 126 EUR in the north (80 for Lombardy), 91 EUR in the centre (54 for Marche), and only 38 EUR in the south (18 for Calabria).

2.1.2. Sites

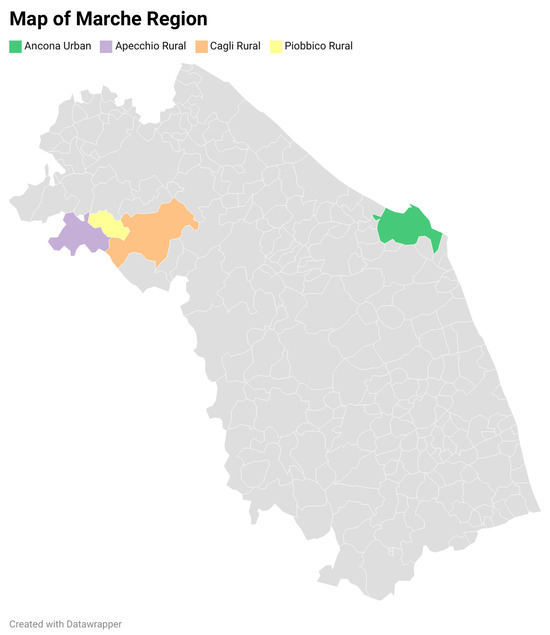

This paper focuses only on forty interviews carried out in Marche region, i.e., in the urban city of Ancona (twenty-four), in addition to Apecchio (three), Cagli (seven) and Piobbico (six), three rural sites located in the inner area “Appennino Basso Pesarese e Anconetano”, characterised by increasing depopulation, a greater presence of older residents, and a scarce availability of health–social services [79]. Two info maps by free data Wrapper Software 2025 “https://www.datawrapper.de/maps (accessed on 18 March 2025)”. present both Italy and the Marche region, the latter with the urban and rural sites that were selected for the survey (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Map of Italy with Marche region.

Figure 2.

Urban–rural sites of Marche region selected for the survey.

2.1.3. Participants

A purposive sampling approach was adopted with the aim of building a typological rather than probabilistic sample, where the characteristics of participants allow an adequate analysis of study topics [80]. The inclusion criteria for identifying frail seniors were the following: male and female seniors aged 65 years and over who live alone at home or at least with a PCA; mobility at home and/or outside their houses with the help of persons or aids; no cognitive impairment hampering the possibility of participants to respond to questions autonomously; and no close family members (i.e., who live in the same urban block/rural building) giving support.

In our study, seniors have thus been selected as almost frail, and a simplified definition of frailty was used, based mainly on old age, functional status, living arrangement, and available support. In particular, the aspect of social frailty, with the absence of help from relatives, services, friends, and neighbours to carry out daily life activities [81], has been stressed. Despite the fact that frailty affects several domains, e.g., physical, clinical, psychological, and socio-economic [82], such a holistic approach would have provided a more comprehensive and precise assessment of this dimension. In particular, measuring frailty in a standardized manner, e.g., using Linda Fried’s Index [83], would have integrated and improved its operationalisation, especially as a clinical syndrome, including important predefined physical frailty criteria (i.e., weight loss, weakness, slowness, exhaustion, slow walking speed, and low physical activity). However, managing such an approach is a complex task [84], as suggested by some studies in the literature, reporting that a great part of frailty screening tools do not assess all relevant dimensions [82]. Following the considerations above, our study adopted a more manageable appraisal of frailty.

In order to recruit sufficient sub-groups of respondents, it was also decided to collect at least 20% of men, 20% of seniors with PCA, 30% with mobility only at home, and 25% with no help from the family. The local sections of voluntary associations (e.g., Auser) and operators from public home services helped with recruiting participants, in particular for checking their eligibility concerning cognitive status and intermediate mobility (based on their own assessments), and for circulating a detailed information letter on this study’s aim, procedure, and privacy safety, in order to explore the overall availability to participate in the survey. Then, addresses and telephone numbers of available seniors were indicated to the research team, in order to fix appointments and proceed with the interviews.

2.2. Instruments, Measures, and Ethical Approval

2.2.1. Topic Guide and Ethical Approval

Two psychologists with long-lasting expertise in qualitative data collection audio-recorded and transcribed in full/verbatim 40 face-to-face interviews at participants’ homes in the Marche region. They used a topic guide with some basic close questions on socio-demographic issues, functional limitations in activities of daily living, and main care supports (e.g., relatives, services). The core of the guide was, however, a set of open-ended questions focusing on several aspects, e.g., health and main pathologies, composition/relations of/with families, life in the built environment, use of services, economic situation, social participation, and perceived loneliness. The interviews lasted around 60–90 min.

For this paper, the narratives regarding the social participation and perceived loneliness were considered, in addition to answers to the close questions mentioned above. Overall, questions were drawn and adapted from previous similar studies [85], and from well-known/standardised research instruments.

The Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic of Milan (POLIMI, Research Service, Educational Innovation Support Services Area, authorisation n. 5/2019, 14 March 2019) approved the study protocol before starting the data collection. Also, participants signed a written informed consent form and were reassured on anonymity and the absolute privacy of their personal/sensitive information.

2.2.2. Daily Life Activities

To detect the difficulties in performing the activities of daily living, ADL and IADL tools [32] were used, integrated by two sensory and two mobility limitations (respectively, seeing and hearing; going up/down the stairs without stopping; and bending to pick up an object) [86,87]. ADLs were as follows: getting into/out of bed, sitting/rising from a chair, dressing/undressing, washing hands and face, bathing or showering, and eating/cutting food. IADLs were as follows: preparing food, shopping, cleaning the house, washing the laundry, taking medication in the right doses and at the right times, and managing finances.

2.2.3. Perceived Loneliness

Open questions on perceived loneliness, such as feelings of being alone and neglected by relatives/friends/others, included the following: “Do you feel alone/abandoned?”; “How much do you feel that others pay attention to what happens to you?”. Loneliness was thus based on self-perceptions of respondents, as reactions to a couple of open questions. We adopted this approach within this qualitative study in order to let older people express themselves as freely as possible. The qualitative and mainly descriptive research design allowed us to “to capture the experience of loneliness narratively” [88] (p. 3).

2.2.4. Social–Leisure Activities

Open questions on social participations included the following: “During last year did you participate in social and leisure activities? If so, how often?”. The interviewer let the interviewee speak freely, and then focused on the social–leisure time activities, which were indicated by seniors; the interviewer asked for more details, and about whether these activities were performed more or less frequently. The interviewer also asked if there were some activities that seniors no longer practice but would have liked to continue. To better manage the topic and guide the respondents (if necessary), the framework/general questions by the Maastricht Social Participation Profile (MSPP) [89] were adopted, which propose some diverse overall types of social–leisure activities, e.g., going to clubs or church; attending cultural events (e.g., cinema, theatre, museum) or other public events (e.g., political union events); meeting family and friends, for instance to have lunch/dinner; playing cards or other games; travelling; and volunteering. We also included some examples of physical leisure activities (e.g., running and walking), as indicated by Hulteen et al. [90]. Finally, we added watching television (TV) and reading newspapers/books, as indicated by Toepoel [6] as further socio-cultural leisure activities. This allowed us to highlight both indoor/in-home and outdoor/out-of-home activities, including those which are conducted individually and based on personal interests (e.g., reading and watching TV), which was also found in the literature [12,91,92]. In particular, solitary activities such as watching TV and reading, which are usually practised alone at home, are considered as social participation, since by performing them, the individual collects important information about what is “happening” within the society/community, thus being more prepared to interact/talk with other persons [1].

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Approach and Dimensions

This study presents both qualitative and quantitative results, with an overall main descriptive mixed-methods analysis, by comparing urban and rural sites of the Marche region selected for our research.

Socio-demographic issues, functional limitations in activities of daily living, and main care supports (collected by means of closed questions) were processed, and respective percentages (univariate and bivariate analyses) were calculated, by using Microsoft Excel 2024 (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, DC, USA). Physical limitations (ADL, IADL, with two sensory and two mobility limitations) were assessed as activities performed autonomously, with the help of a person or aid, or not performed (senior is “not able”), and then four levels of impairment were considered: mild, moderate, high, and very high, when no activities labelled “not able”, one-two, three-four, and five or more were reported, respectively [93].

The qualitative approach of this study adopted the research paradigm of interpretivism [94], focusing on the in-depth exploration of the lived experiences of participants, and related interpretations and constructions of knowledge/reality, to understand the meaning underlying social/cultural behaviours and habits of individuals. Interpretivism usually utilises qualitative methods (e.g., interviews, observations) and also analyses the context within which social contacts/interactions develop. For the qualitative analysis (social participation and loneliness), co-authors (MGM, MS, GL, and SQ, senior sociologists/gerontologists, with expertise in formal/informal caregiving and needs of frail older people) used the Framework Analysis Technique [95]. The related five standard steps are the following [96]. (1) Careful line-by-line reading of transcribed narratives (MGM and SQ). (2) Identification of macro sub-categories, starting from the preliminary conceptual framework that was adopted to build the semi-structured questionnaire/topic guide (MGM, SQ, and MS). (3) Indexing and labelling, i.e., the identification of codes by means of both deductive (from theoretical-based definitions included in the topic guide) and inductive (further concepts emerged during the data collection) approaches (MGM and SQ). (4) Building of thematic charts for where to insert transcriptions, according to respective respondents (rows) and categories (columns), and refining emerging patterns and identifying headings and subheadings (MGM and SQ). (5) Interpretation of the qualitative findings, with deep and recurrent discussions within the research team, especially to manage possible disagreements (MGM, SQ, MS, and GL). Then, a thematic content analysis was provided (MGM and MS) [97]. This was assessed manually, without using dedicated software, as suggested by some authors [98,99], in order to develop the maximum possible familiarity with the responses and possible relationships among themes. It is worthy to clarify that the steps mentioned above are more indicated for an inductive (bottom up) qualitative analysis, whereas in our study, we also used a deductive (top down) method, with theoretical-based definitions of categories representing the “route map” for the overall analysis [100]. Moreover, a preliminary tree of the main macro/sub-categories, and labels, was drafted in our study based on the topic guide, as an additional step to better construct the “skeleton” of the thematic charts. Each chart was thus dedicated to one macro-category and relevant sub-categories, and also distinguished between urban and rural sites, by using Microsoft Excel 2024 sheets (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, DC, USA), as a comprehensive matrix for summarising the excerpts from the narratives [80].

The subjective perceived loneliness was further classified into four levels: absent/mild, if this feeling is not or rarely perceived; moderate, if this feeling is sometimes perceived in particular circumstances (e.g., at night, during the weekend, on Christmas or Easter day), but it is almost never reported as an intense pain; high, if this feeling is often perceived as almost intense; very high, if this feeling is very often perceived as very intense, with consequent insomnia, anxiety, and depression [101,102].

To perform the social participation analysis, including social–leisure activities, various classifications from the literature were followed [1,2,14,37,89,90] and subsequently integrated/adapted with the qualitative results that emerged from the survey. Thus, we maintained the composed term social–leisure activities as suggested by previous authors, and as reported from seniors participating in this study, who often did not distinguish a clearer connotation of “social” from “leisure” concerning an activity, since both meanings could identify the latter. Seven main themes/macro-categories and twenty-three sub-categories were defined. Watching TV was considered as a particular/eighth macro-category (without sub-categories), because it implies the consumption of mass media/entertainment, and thus represents both a recreational and cultural activity. This choice is also supported by some authors [103,104]. The coding included the following for all the categories: activities performed weekly, monthly, or less often; and activities no longer performed, but that seniors would still continue. Also, in some cases, respondents mentioned some obstacles hampering social participation (e.g., reduced mobility, economic status, accessibility of the environment, existing social contacts/relations). The final categorisation in the macro and sub-categories of social participation is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

The process of categorisation.

It is worth clarifying that we did not specify between offline and online participation, and thus we did not include, as a further category, “online/digital social participation”, i.e., computer and internet use [105,106,107], since this possibility could cross several offline activities that we considered for the analysis in Table 1 (e.g., religious, cultural, sports, recreational).

2.3.2. Quantification of Statements and Quotations

The qualitative dimensions were further quantified (MGM and MS) by means of Microsoft Excel 2024 sheets, as frequency/count of statements, i.e., presence or absence of the different categories (activity: reported/not reported), with the aim to introduce a synthetic picture for each main theme. This was a “qualitative to quantitative” approach for analysing a study with a “qualitative” prevalent direction/asset [108]. Therefore, the quantification represents a simple numeric presentation/measurement of accounts that emerged from the narratives, and the qualitative analysis enriches and integrates the quantification, allowing a more in-depth understanding of the overall lived experiences of seniors. Also, comparisons between urban and rural sites of the Marche region were provided. In particular, statements were firstly counted for each activity (sub-category) and differentiated between those still performed and abandoned. Regarding the frequency of the former, it was considered without distinguishing by type of activity, to analyse how many seniors reported weekly, monthly, or less often activities overall. Macro-categories of social participation were also used to make additional simple bivariate analyses, which aimed to explore possible relations of activities still practised with levels of both physical limitations and subjective perceived loneliness of the study participants. For this purpose, only two aggregate levels of these dimensions were considered, i.e., absent/mild/moderate and high/very high levels of loneliness; and mild/moderate and high/very high functional limitations. Macro-categories of social participation and aggregate levels of both loneliness and functional limitations were used for these elaborations, to avoid an excessive dispersion of data due to a rather small sample (n = 40), and they are also divided between urban (24 units) and rural (16 units) respondents. This is used to specify that, to make the cross elaborations mentioned above, at least one activity reported in the macro-category was considered as a positive answer (e.g., “yes” in one or more sub-categories of a macro-category, corresponds to one “yes” in the latter), without summing the number of the related single sub-categories of activities. This is used to focus on the number of macro-categories pertaining to respondents (and not on the number of activities performed by seniors in each macro-category).

Tables (apart Table 1 above) present both percentages (%) and absolute values (n), which do not correspond to respective totals when the number of responses (numerator) are higher (each senior can provide multiple answers) or lower (no statements by some senior) than the number of respondents (denominator). In some cases, percentages values have been rounded to simplify the overall reading of results. Also, following the quantification of qualitative findings with a “qual to quant” approach, the standard deviation (SD) and significance level (p) values are not included because of the main qualitative orientation of this study, where quantitative data are not primary results requiring a statistical appraisal.

Relevant excerpts/verbatim statements of the transcripts have been integrated in the whole analysis as quotations [109], to better interpret and “enrich” the information shown in the tables. With regard to the relationship between social participation and level of functional limitations and perceived loneliness, quotes from seniors who cannot perform certain activities anymore are also reported to further integrate and support the overall analysis of findings. Each quotation was translated and indicated by a code including the site (“urb” when urban; and “rur” when rural) and the progressive interview number (1–24 urban; 1–16 rural).

2.3.3. The Trustworthiness of the Qualitative Data Analysis

To assure its trustworthiness, the four criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba [110], i.e., the credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the qualitative data analysis were followed. The use of a topic guide partly “inspired” by previous similar studies on frail older people [85] and the refinement of the protocol (rules for data collection and analysis) by means of several ad hoc meetings among researchers, assured the credibility. A deep literature review served as the background for setting up the initial conceptual framework and assured the transferability [18]. A detailed and well documented/replicable study protocol, accurate field notes on the whole process, and interactions among the research team and interviewers, assured dependability and confirmability [111]. The section ‘Materials and Methods’ has been partly drawn from a previous publication of authors [70], where further and more detailed information on the setting, sampling, measures, and data analysis, regarding the main “IN-AGE” study, is available.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Overall, participants in the Marche region were mainly aged 80 years and over, female, with a low/medium educational level, widowed, living alone, with a mild/moderate level of functional limitations, with support coming especially from family members and less from services. The urban site is characterised by some younger and more educated seniors, the presence of some divorced/separated besides widowed seniors, more seniors living without a PCA, and seniors who are more supported by services besides families. Rural sites are characterised by older seniors and more seniors without a study qualification/diploma, the presence of some single persons besides widowed seniors, more seniors living with a PCA, with a better level of functional limitations, and greater support from families (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics, functional limitations, and main care supports.

3.2. Social–Leisure Activities of Older People in Urban and Rural Sites of Marche Region: The Count of Statements

3.2.1. Types of Social–Leisure Activities Still Practised

The analysis of social–leisure activities still practised by older people in Marche region is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Types of social–leisure activities still practised (n = number of statements/absolute values).

Seniors report to be involved mainly in receiving/making visits (73%), watching TV (63%), participating in lunches/dinners with family members and friends (53%), attending religious functions (50%), and walking (45%). Fewer seniors still attend social clubs and playing cards or other games. Overall, rural seniors are more active than urban ones with regard to all activities, in particular receiving/making visits (94% vs. 58%), watching TV (94% vs. 42%), walking (75% vs. 25%), and attending religious functions (69% vs. 38%). No participation in activities of political parties or trade unions was reported in both urban–rural sites (Table 3).

Regarding the overall frequency, monthly and less often activities prevail in both sites and the region. However, weekly activities prevail in rural sites (Table 4).

Table 4.

Frequency of social–leisure activities still practised (n = number of statements/absolute values).

3.2.2. Types of Social–Leisure Activities No Longer Practised

The analysis of social–leisure activities no longer practised by some older people in the Marche region, but that they would still like to practise, highlights mainly religious functions and walking (18% both), unpaid volunteering and playing cards or other games (13% for both), and attending shows, music concerts, cinema, theatres, museums, and conferences (10%). Seniors living in rural sites emerged as those which are more “nostalgic” concerning several social–leisure activities they do not perform anymore, especially attending shows, music concerts, cinema, theatres, museums, and conferences, in addition to playing cards or other games, and walking. Watching TV is the only activity never reported as no longer practised in both sites (Table 5).

Table 5.

Types of social–leisure activities no longer practised 1 (n = number of statements/absolute values).

3.2.3. Macro-Categories of Social–Leisure Activities Still Practised

The grouping of single types of activities still practised in macro-categories (at least one in the group) highlights a greater participation in social/religious activities (88%), followed by watching TV (63%) and practising sports/physical exercises (48%) in the Marche region. Also, this grouping confirms and reinforces the overall greater involvement of rural seniors compared to urban ones (Table 6).

Table 6.

Macro-categories of social–leisure activities still practised (n = number of statements/absolute values).

3.2.4. Macro-Categories of Social–Leisure Activities Still Practised and Level of Functional Limitations

Overall, seniors in the Marche region with mild/moderate physical impairments (twenty-four vs. sixteen with a higher level of impairment) practise activities pertaining to a greater number of macro-categories than those with worse levels (seven vs. five), especially social/religious activities (92% vs. 81%), watching TV (67% vs. 56%), and cultural events (25% vs. 19%), in addition to productive–artistic activities and travelling (with lower percentages), which are performed only by seniors in better functional conditions. However, surprisingly, other activities are slightly more reported by older people with a higher level of physical impairment, i.e., sports/physical exercises and also recreational activities (Table 7).

Table 7.

Social–leisure activities still practised and functional limitations in Marche region. (n = number of statements/absolute values).

A similar picture emerged in urban sites (with twelve reporting both lower and higher level of functional limitations), where seniors with mild/moderate physical impairments reported activities pertaining to a greater number of macro-categories than those with worse levels (seven vs. five), especially social/religious activities (83% vs. 75%), cultural events (25% vs. 8%), and recreational activities (25% vs. 17%) (Table 8).

Table 8.

Social–leisure activities still practised and functional limitations in urban site of Marche region (n = number of statements/absolute values).

Productive–artistic activities and travelling (8% both) were reported only by seniors in better functional conditions. Sports/physical exercises are more reported by seniors with higher physical difficulties. Watching TV is equally reported by all seniors living in urban sites independently from their physical status (Table 8).

In rural sites (level of functional limitations lower for twelve and higher for four), seniors with a lower level of physical limitations perform activities pertaining to a greater number of macro-categories than those with worse levels (seven vs. five), e.g., sports/physical exercises (83% vs. 50%), travelling, and especially productive–artistic activities, all of which were reported only by older people in better conditions (respectively, 8% and 33%) (Table 9).

Table 9.

Social–leisure activities still practised and functional limitations in rural sites of Marche region (n = number of statements/absolute values).

In rural sites, seniors with a higher level of functional limitations perform more activities, such as attending cultural events (50% vs. 25%) or recreational activities (50% vs. 8%), and all watch TV. This also represents a social–leisure option for 92% of seniors with a better level of functional limitations. Social/religious activities are equally reported by all seniors living in rural sites independently from their physical limitations. Moreover, it is worth considering that seniors with a lower level of functional limitations perform some activities (e.g., social/religious and sports/physical exercises) more in rural sites than in urban ones (respectively, 100% vs. 83% and 83% vs. 8%) (Table 9).

3.2.5. Macro-Categories of Social–Leisure Activities Still Practised and Level of Perceived Loneliness

In the Marche region, older people reporting absent/mild loneliness (22 units, vs. 18 with higher level) still carry out some activities more than those with a high/very high level of loneliness, especially watching TV (68% vs. 56%), participating in recreational activities (23% vs. 17%), and travelling (9% only for seniors with lower levels of loneliness). Conversely, social/religious and sports/physical exercises are slightly more practised by seniors with higher levels of loneliness, who moreover perform more productive–artistic activities (Table 10).

Table 10.

Social–leisure activities still practised and perceived loneliness in Marche region (n = number of statements/absolute values).

A more positive link emerged in urban sites (Table 11).

Table 11.

Social–leisure activities still practised and perceived loneliness in urban site of Marche region (n = number of statements/absolute values).

In urban sites, indeed, older people with absent/mild loneliness (16 units) still carry out almost all social–leisure activities more than those with high/very high levels of loneliness (eight units), especially social/religious activities (81% vs. 75%), watching TV (56% vs. 13%), sports/physical exercises (31% vs. 25%), recreational activities (25% vs. 13%), and cultural events (25% only for seniors with lower levels of loneliness) (Table 11).

Among rural seniors, those with absent/mild loneliness (six) still carry out some social–leisure activities more than those with high/very high levels of loneliness (ten), especially watching TV (100% vs. 90%), practising sports/physical exercises (83% vs. 70%), and performing productive–artistic activities (33% vs. 20%). However, the participation in cultural events/activities and recreational activities is higher among seniors with greater levels of loneliness, whereas attending to social/religious activities emerged equally among seniors with lower and higher levels of loneliness (Table 12).

Table 12.

Social–leisure activities still practised and perceived loneliness in rural sites of Marche region (n = number of statements/absolute values).

3.3. Social–Leisure Activities of Older People in Urban and Rural Sites of Marche Region: A Storytelling by Oder People

3.3.1. Activities Still Practised

In both urban and rural sites, seniors report social–leisure activities they still practise, but the latter report more activities than the former, especially regarding watching TV and receiving/making visits.

I visit friends I am most familiar with. (Rur-11)

I exchange a few visits with some old friends, those a little freer from grandchildren. (Urb-3)

In some cases, seniors report watching TV for many hours each day, thus reducing both the desire and time for reading a book.

I watch a lot of TV. I always have the TV on. (Rur-11)

By watching TV too much I have also lost the habit of reading. I have become addicted to TV! The fact of having the immediate image, the immediate word, without effort, evidently takes away my desire to read. (Urb-14)

Also, walking and religious functions are more reported by rural seniors. It is also worthy to highlight two urban seniors who have the possibility of going on walks which are organised by the day care centre they attend.

I often go for walks with friends when they come to visit me. (Rur-16)

I am happy to walk with other seniors that attend with me a day care centre. (Urb-23)

For some rural seniors, having lunches/dinners with relatives/friends happens a little more frequently. However, some economic issues make it difficult to frequent restaurants, and some seniors prefer to eat only a pizza for its cheaper cost. When possible, a senior in an urban site organises a lunch with the family, which offers an important occasion to spend time all together.

Sometimes on Sundays I go out to eat with two friends. But not often, it is also a question of money! (Rur-10)

I use to go for a pizza with my friends. (Rur-3)

When I go out, we mostly go out to eat pizza together. (Rur-5)

Three or four times a year, for instance at Christmas, Easter or for my birthday, I have lunch at a restaurant with my family. I pay, and I want to do it to bring the family together, children and grandchildren and sometimes my sister too. It is really important to me! (Urb-19)

Also, in urban sites only, two seniors report having gymnastics/rehabilitation at the day care centre they attend. In rural sites only, some seniors participate in parties/festivals. In both sites, seniors read book and newspapers (slightly more in the rural one).

I practice some gymnastic activities, for instance rehabilitation, at the day care centre, where an operator trains me to walk twice a week with a walker. The centre organises also animation activities. (Urb-20)

If there is a festival, even a parish celebration, I am always the first one to go. (Rur-11)

I like reading, I dedicate most of my time to that. (Rur-15)

I read books and magazines. I really like it, since I was a little girl. (Urb-15)

Moreover, rural seniors reported more cases of hobbies, for instance growing vegetables, and they also attend cinema/theatres, and provide unpaid volunteering. However, in an urban site, a senior takes care of his garden and plays the piano.

I have a small vegetable garden that I cultivate. I like to keep it clean. I spend time there. (Rur-12)

Whenever possible I go to the theatre with my daughter. (Rur-14)

I have offered my availability to help cleaning the church in preparation of some charity evening. I can do this but nothing more. (Rur-11)

I take care of plants on my terrace. I like doing it. I also like to play the piano sometimes. (Urb-21)

Concerning less performed activities, such as participating in cultural groups, playing cards or other games, and making voyages, urban and rural seniors reported similar situations. Regarding voyages, they mainly attend organised trips for seniors.

The library organises a nice initiative in the winter. Somebody chooses a book and the following month everyone comments it in a group, and I participate because I like reading, I dedicate most of my time to that. (Rur-15)

I attend a neighbourhood club quite regularly, with other seniors like me. We play cards. (Urb-8)

I play burraco with friends, sometimes at my house and sometimes at their house. (Rur-10)

I like burraco and every afternoon my sister and some friends come to my house to play together. (Urb-6)

In the summer I take part in some holiday trips organised for older people. We go to the seaside on our region’s coast. (Rur-3)

Seniors also reported some social activities that they consider as very important occasions to have relationships and talk with other persons: frequenting bars and the hairdresser in urban sites, and visiting older people in nursing home in rural sites.

Every morning, I go to the bar for a coffee. There I meet several people, we talk. (Urb-13)

When I go to the hairdresser, I like it also because I talk to other ladies. (Urb-24)

I visit older people living in nursing homes. I go with some friends. We spend some time together. (Rur-12)

3.3.2. Activities No Longer Practised but That Seniors Would Still Like to Practise

Compared to urban sites, in rural ones, there is a higher number of seniors that do not perform social–leisure activities anymore, e.g., attending cinema/theatres, playing cards or other games, and walking. This often happens because some relatives/friends are too old or even dead.

I used to go to the theatre with my husband. Since I am a widow, I do not go there anymore. (Rur-13)

In the past years we used to meet to play cards. Currently we do not do this not anymore, because the other players are all older than me, and the younger ones do not play cards. (Rur-11)

Now between one thing and another we do not see each other anymore, also because someone has died. (Rur-12)

Regarding other activities no longer practised, from the narratives (both by urban and rural seniors), some particular situations emerged regarding seniors who avoid performing activities with others they do not know, or in cases of widowed seniors.

I would like to attend a social club, as I did in the past, but the fact that I do not know other persons who could share this activity with me represents a strong obstacle. (Rur-15)

I used to travel with my husband, but now that I am a widow I do not want to travel with other couples, because I feel uncomfortable among them. They pay too much attention to me, and it seems to me that I am almost a burden, so I avoid it. (Urb-18)

Rural seniors in particular complain about the lack of dedicated spaces allowing seniors to meet and spend time together.

Here we have no spaces to meet with other older people. There is only the nursing home! (Rur-1)

Where I live, we lack a club for seniors. A cinema is lacking too. There is only a tobacconist, we meet there. (Rur-7)

I would really like to have places to meet with other seniors, a recreational place dedicated to us! (Rur-5)

Some urban seniors, however, reported that they do not perform social activities anymore, and that do not care to practise them again. This, however, depends on the necessity to adapt activities and lifestyles to their own capacities.

I do not want to do anything anymore. I do not have great relationships with anything. (Urb-1)

I do not practise any activity with other people. When I go out, I feel “out of the world”, I am not comfortable! (Urb-22)

My current bad physical situation prevents me from moving freely, from taking long walks, and so on. However, I am calm, I do not feel the need of such activities. My needs have changed with ageing, and thus I have adapted to do what is still possible for me. (Urb-18)

Also, the presence of cobblestones in rural sites makes moving in old age more difficult and puts seniors at risk of falling. Moreover, public transportation services are scarce/lacking in rural sites, and this represents a further obstacle for outdoor activities.

The streets are made of cobblestones and when I walk, I fear falling! (Rur-1)

The bus has a short timeline, only few trips a day! (Rur-9)

3.3.3. Activities Still Practised and Physical Limitations

Overall, older people living in both urban and rural sites with mild/moderate physical impairments report more social–leisure activities they still perform than those with worse physical conditions. This context applies especially to recreational, cultural, and social/religious activities in urban sites. Thus, higher functional limitations hinder seniors from carrying out several social–leisure activities in both sites. Within the social/religious group, it is indeed more frequent for seniors to receive visits from friends and relatives in their own home, instead of going to visit others, since some functional limitations reduced the mobility of respondents. Regarding lunches/dinners with relatives/friends, some digestive and eating problems make it difficult to frequent restaurants. Also, mobility problems represent an obstacle to practise volunteering.

Since my health has worsened, I move little. My friends come to visit me. (Urb-7)

My children often invite me out to eat at a restaurant, but this is a problem! I cannot eat what I want, I have to be careful. (Urb-24)

I spent almost two years volunteering for older people. I entertained them with games and I also accompanied them home. I cannot do the latter anymore. Because I use a stick to walk and thus, I fear I cannot appropriately support others. I am afraid of making them falling. (Urb-16)

Mobility problems reduce and modify participation in religious functions, by transforming the setting from outdoor (e.g., a church) to indoor (e.g., via radio/TV at home), thus also allowing frail seniors to still attend them. This “arrangement” was reported both in urban and rural sites.

I only hear Mass on the radio, the church is far away and I cannot go there. My knee is in bad shape! (Rur-5)

I am not so well. I watch Holy Mass on Sundays on TV. Then the priest comes to bring me Communion at home once a month. (Rur-16)

I used to always go to church, but now I cannot and thus I listen to Mass on TV every morning. (Urb-13)

In rural sites, seniors with a lower level of functional limitations also perform more sports/physical exercises, mainly walking, and some mobility problems and a lack of energy due to old age sometimes reduce but do not hamper these activities. Also, regarding gymnastics, a rural woman did not report performing gymnastics, since she does not attend a gym, yet she found a “domestic/indoor” alternative.

I walk a lot. I like going out with friends or with my niece. However, I do not walk for long distances because I get tired. I take a lot of short walks. (Rur-13)

I go for walks but I have to be careful, now I walk badly and I am afraid of falling. (Rur-14)

I do not go to the gym. I have trouble moving. My daughter does yoga and taught me how to do some exercises that I can do alone at home. (Rur-11)

Conversely, in urban sites, six seniors in worse conditions perform more sports/physical exercises, but this regards two seniors (as already reported above) performing some gymnastics and walking at the day care centre they attend, and other older people participating in walking organised by the parish; thus, they are supported in these activities. Also, an older man reports takinglittle walks despite his bad physical conditions.

I do rehabilitation and walks organised by the day care centre. (Urb-23)

I go on mountain walking which are organised by the parish. (Urb-4)

I take short walks every day with a stick, but I walk badly, slowly and I stop often. (Urb-16)

In rural sites, two seniors with a higher level of functional limitations perform more activities such as cultural and recreational activities, but they play cards at home and read books or newspapers, which are activities not requiring a great mobility.

For Easter and Christmas I go to my sister’s house or she comes to mine and we play cards. (Rur-8)

I read the newspaper, it helps me pass the time and feel less alone. (Rur-10)

In both sites only seniors in better physical conditions report travelling. However, the fear of travelling alone in old age also emerged, since seniors feel frail and unsafe.

Sometimes I go to visit a daughter out of my region. However, I am old and I feel less and less safe traveling alone. I am afraid to be alone for three hours on the train, without some relative. What if I feel sick during the travel? (Urb-15)

No difference based on functional limitations emerged with regard to watching TV in urban sites, and all four seniors with higher functional limitations do this in rural sites. Sometimes, watching TV represents the main way to pass the time, especially when going out alone is not possible anymore, also due to difficulties in taking a bus.

I cannot go out alone anymore, because otherwise I fall. Also, I cannot take the bus alone. In fact, I used to take the bus, I did volunteer work, I played burraco, I went on trips. Now I spend almost all my time at home watching TV, and many times I get bored, it is not a nice life. Sometimes my grandchildren come to visit me, but they also have their own commitments! (Urb-9)

Now I cannot do many activities anymore. Some years ago, I had a more active life, I went out, I went to the market, I met people, I talked with other seniors. Now I only watch TV. I watch a lot of TV, maybe too much! (Urb-10)

However, some visions problems can limit even this simple activity.

I watch TV but I do not see it, I just listen to it. (Rur-3)

Often, reduced mobility, and thus the need to be accompanied, hamper all social activities or at least limit a lot of social activities in both urban and rural sites.

I do not go to parties because I cannot move alone. Nobody takes me there! (Rur-16)

I would like to be active in politics again. In the past I was more active, now I have some physical problems and I should be accompanied. I would like to have such a commitment, not only to spend time, but also to do something good for the society. (Urb-3)

I cannot go anywhere! To be able to move I need someone who would accompany me! (Urb-7)

Regarding activities no longer practised but that seniors would like to continue, some rural seniors who performed several social–leisure activities in past years emerged. Currently, old age and reduced mobility, even though not particularly severe, do not allow such a lifestyle anymore.

When I had a better health, I did volunteering activity, went to cinemas and museums, and played cards. I took a lot of walks. Now I would like to do all these things as in the past, but I cannot walk well on my own anymore, I cannot even go shopping alone. (Rur-3)

I was active in politics, I did volunteer work, I used to travel and take long walks. I cannot do anything anymore! (Rur-10)

3.3.4. Activities Still Practised and Perceived Loneliness

Both urban and rural seniors with lower levels of loneliness continue carrying out some social–leisure activities more than those with higher levels of loneliness, especially watching TV.

To overcome some moments of loneliness I turn on the TV and make zapping. I go back and forth among channels until I find something that gives me a bit of joy, or that engages me in thinking a little. (Urb-14)

I am calm, I do not get down, even if I spend a lot of time alone, the TV is always on, it keeps me company. I also have a lot of people close to me. I am fine like this. (Rur-2)

This positive picture also emerged in urban sites with regard to social/religious, cultural, and recreational activities, and in rural sites for productive–artistic activities. These activities are indeed more carried out by seniors reporting lower levels of loneliness.

I do not feel alone. I always see my children. They come to visit me very often. (Urb-5)

If there is some cultural event, I am invited and accompanied. I am happy to go. (Urb-13)

Spending time with my burraco friends, talking to them, helps me a lot. (Urb-6)

I have a small vegetable garden near the river, and take care of it keeps me company. (Rur-7)

An urban woman still performs several activities and reports she does not feel loneliness at all.

I am fine, I do not feel alone because my children call me and come to visit me all the time. I am fine alone, I watch TV, then I do crosswords. I also go out and I meet many people and we talk together. I also talk a little with the parish priest who gives me strength. (Urb-24)

Conversely, some seniors who miss to see their relatives and friends and talk with them reported higher levels of loneliness in both urban and rural sites.

I spend little time with the family, at least lunches or dinners only at Easter and Christmas, twice a year. I feel alone (Urb-12)

I would like to see my daughters more often. I also miss my village dinners, which I cannot longer have. I feel isolated, and these moments weigh on me, especially when my friends have dinners together and do not invite me! (Rur-9)

It is hard for me to be alone, I would like to see friends, to spend time with them, to go out and chat with them. (Rur-4)

What weighs on me most is the lack of company. The company of friends is what I need most. I would like to meet other people, go out more often. (Rur-1)

Two urban seniors report they do not perform anymore any activities (apart watching TV);thus, they feel a deep loneliness.

I feel a deep sense of loneliness, because being always at home, seeing only these four walls, makes me feel extremely melancholic. It is like a prison and I cannot stand it anymore. I was so dynamic, I practised many activities, and now I do not do anything anymore. This is not a nice life! (Urb-9)

I do not make any activity anymore. Everything has “decayed” since I got old. I feel like I have nothing left. I am alone. (Urb-11)

However, some rural and urban seniors reported greater levels of loneliness, especially when a partner or spouse is missing, even though they still perform some social–leisure activities.

I receive visits from my friends. Once a week with my friends we go to eat at the restaurant. I go to the UNI-3. Two or three times a year I go to the theatre to listen to music. Every day I go for walks with a stick. Yet I often feel alone, my moments of solitude weigh on me, I miss a male companion. (Rur-8)

Sometimes I go with friends to eat at the restaurant. I go to Mass every day. I also play burraco, I always watch TV. When the theatre is open, I go about once a month. However, I feel loneliness! (Rur-10)

I spend every Sunday with my daughters, but despite this I feel alone. (Urb-15)

I feel alone even when I spend time with my family. The problem is that I am widow! (Urb-18)

In some cases, seniors “simply” link loneliness to frailty in old age, rather than to the activities carried out or not.

The older you get, the more fragile and alone you become. Sometimes the hours are long and so heavy! (Urb-1)

It is worthy to highlight that some seniors (from both sites) report simply talking with other seniors as a measure that helps them in combating loneliness.

I do not feel loneliness, because I chat a lot with old friends also by smartphone. (Urb-2)

I do not feel lonely. I meet friends, and we chat. (Rur-11)

4. Discussion

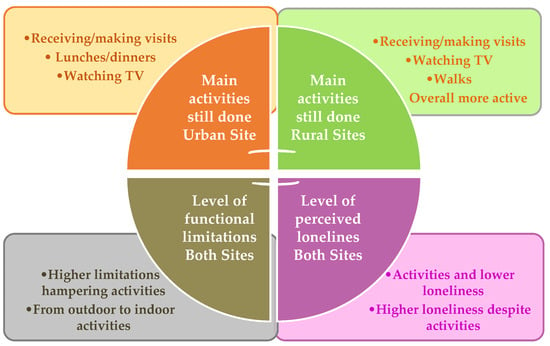

The aim of this study was to analyse the social participation of frail older people ageing alone in place in both urban and rural sites of the Italian Marche region. Partly differently from what hypothesized, overall, rural seniors were more involved than urban ones in social–leisure activities. However, as a general picture, older people with mild/moderate physical impairments living in both sites report performing more social–leisure activities than others with worse physical conditions. Also, more active participants feel less lonely in both sites, even though some reversal situations also emerged, indicating that loneliness is a personal perception. The main contents that emerged from this study are summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Framework of the social participation of frail older people from this study in Marche region.

It is worth noting that activities are discussed by single type/sub-categories, whereas associations with functional limitations and loneliness are discussed by macro-categories, with insights on sub-categories when relevant. Also, throughout the Discussion, comparisons between urban–rural areas are presented. Finally, national/international data are mainly considered for the discussion, since local information regarding the topic of social participation of seniors in the Marche region is scarce.

4.1. Social–Leisure Activities Still Practised by Older People in Urban–Rural Sites

In our study, seniors living in Marche region mainly reported receiving/making visits, watching TV, and having lunches/dinners with family members and friends. Religious functions and walking follow. Other authors support these general findings for Italy [29], since they found that the most frequently performed social activities concern visits and lunches/dinners, at or out of home, in addition to some outdoor activities, e.g., walks.

Data on the overall social participation of seniors in Italy in 2023 [112] indicate that this decreases with age (from 27% for people aged 65–74 years to 8% for people aged 85 years and over), and is lower among those who live alone (18% vs. 21% cohabiting with others). However, ISTAT [67] reports that about 46% of older Italians meet friends at least once a week, and about 48% report frequent contacts with non-cohabiting family members. Other international sources support our results. For instance, Baeriswyl and Oris [113] suggest how sociability practices belonging to the private sphere, e.g., visits to/from relatives and friends, are very common and particularly meaningful for older people. Adams et al. [12] indicate that visiting friends is particularly enjoyed by seniors, with a positive impact on their wellbeing. Also, Björnwall et al. [114] stressed the importance of “commensality”, i.e., sharing meals in older age, as potentially improving their nutritional status and wellbeing. Frequenting restaurants together, however, depends on their own economic situation, as reported by our respondents. Some authors more generally indicate the socio-economic status of persons, especially in old age, as a crucial factor leading to disparities in social participation among them [115,116].

Watching TV represents an activity that our respondents carry out even for several hours each day. According to ISTAT data for Italy [67,104], almost 95% of seniors have the “habit” of watching TV for almost five hours per day, compared to about three hours for young people. Watching TV is thus a social activity/experience [117], with some programs also strengthening civic participation, and overall allowing them to remain updated [118]. Furthermore, seniors still remain a part of the population with fewer skills in using new technologies and therefore are very attached to TV [119].

Also, religion and overall spirituality are important aspects for our respondents. In particular, the literature highlights that church attendance/religious participation is more frequent among older than young people, and this representing a cohort effect [113]. Religion can indeed provide support and comfort to seniors and offers them a sense of belonging to a community [120]. Other studies [118] showed that such a feeling, more generally regarding the involvement in associations (including churches), can encourage seniors to be engaged in social participation. More recently, McManus [121] suggested that religious practices involving spirituality are important to mitigate/support age-related occurrences (e.g., chronic disease), since they promote social contacts in the living community and improve wellbeing.

Regarding walking, which is also mentioned among activities practised by our seniors, ISTAT data for Italy [104] show that active movement (on foot or by wheel) involves about 60% of young people between 15 and 24 years, but also 52% of seniors. Among the former, there are those who do not yet have a driving license or even a car at their disposal. Among the latter, there are mainly those who no longer feel like driving or maintaining a car, especially when it is used rarely. Further, data for Italy in 2023 [112] highlight that 18% of seniors have participated in organised trips or stays. Some international studies suggest that increasing the level of physical activity of older adults could in turn increase their possibility of ageing independently in place [122]. However, even though the additional free time available to pensioners over 65 years of age could allow greater physical activity for them, this context becomes worse as people become older, especially for those aged 75 years or more [66].

In our study, overall, rural seniors in the Marche region are more active than urban ones, i.e., a greater number of them perform social–leisure activities, in particular receiving/making visits, watching TV, and walking. Receiving/making visits, having lunches/dinners, and watching TV also prevail in urban sites, but with lower percentages. As a first consideration, it is worth noting that rural seniors in our study are more concentrated than urban ones in the lower level of functional limitations (75% vs. 50% with mild/moderate level), and this in turn probably impacts the greater participation of the former in some activities. Apart from this internal result, and according to the previous literature, in rural sites of Italy, there is a scarce provision of public services for older people [123], who often rely on informal care networks, such as relatives and especially friends/neighbours [124]. This could indirectly allow receiving/making more frequent visits. Also, in rural sites, the closeness and availability to/of the natural/green environment allows for the possibility of taking a walk and contributes to the wellbeing of seniors [58,125]. It is also worth highlighting that two urban seniors participating in our study can have walks and gymnastics/rehabilitation sessions since they attend a day care centre. This represents a great opportunity for them. The literature also revealed how day care centres can provide spaces where older people can be more active and healthier [126].

According to our results, no senior in the Marche region reported participating in activities of political parties or trade unions. Some ISTAT data for Italy [67] indicate that the political participation of seniors is low and mainly indirect, by exchanging/comparing their own information with each other, also when these are taken from newspapers or TV, which are the only sources of political information for over four out of ten seniors. A study based on data from the European Quality of Life Survey (EQLS) conducted in 33 countries [127] and exploring levels of political participation among people aged over 65 years, found overall lower values in southern (including Italy) and eastern Europe, and higher in northern/western European countries. The same study also found that a higher level of social trust was associated with a lower likelihood of political participation among older people; however, this represents an individual choice, but also depends on the societal context of countries.

4.2. Social–Leisure Activities No Longer Practised by Older People in Urban–Rural Sites

Only few seniors in the Marche region talked about their greater sociality in past years, with activities no longer practised but that they would still like to perform, especially religious functions and walking, followed by unpaid volunteering and playing cards or other games, and overall cultural activities (e.g., attending shows, music concerts, cinema, theatres, museums, and conferences). Watching TV is the only activity never reported as no longer practised by our participants in both sites.