Integrating Socio-Demographic and Local Sustainability Indicators: Implications for Urban Health and Children’s Vulnerability in Henequén Neighborhood in Cartagena, Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Questionnaire and Characterization

2.3. Local Sustainability Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characterization

3.2. Housing Conditions

3.3. Access to Basic Services

3.4. Living Conditions

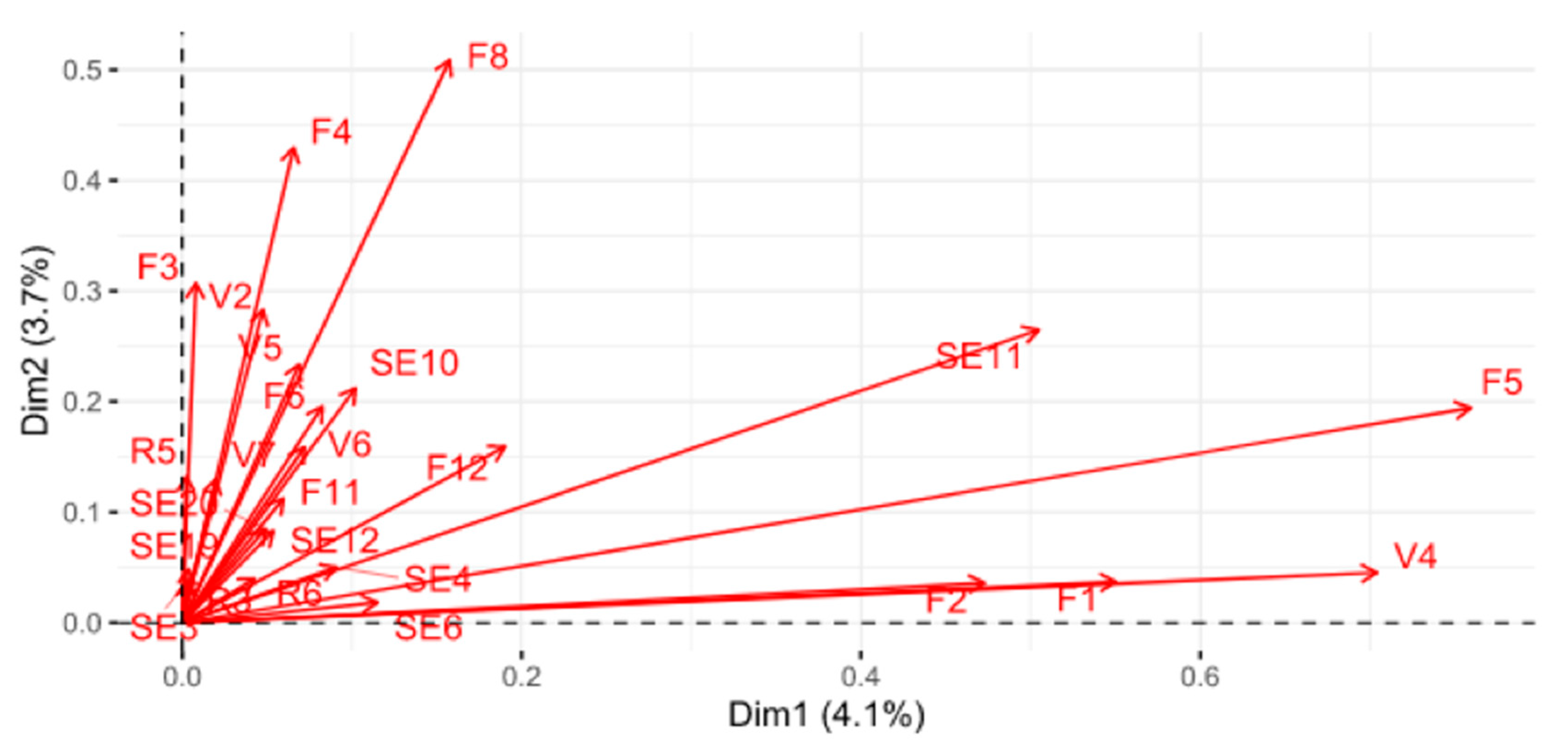

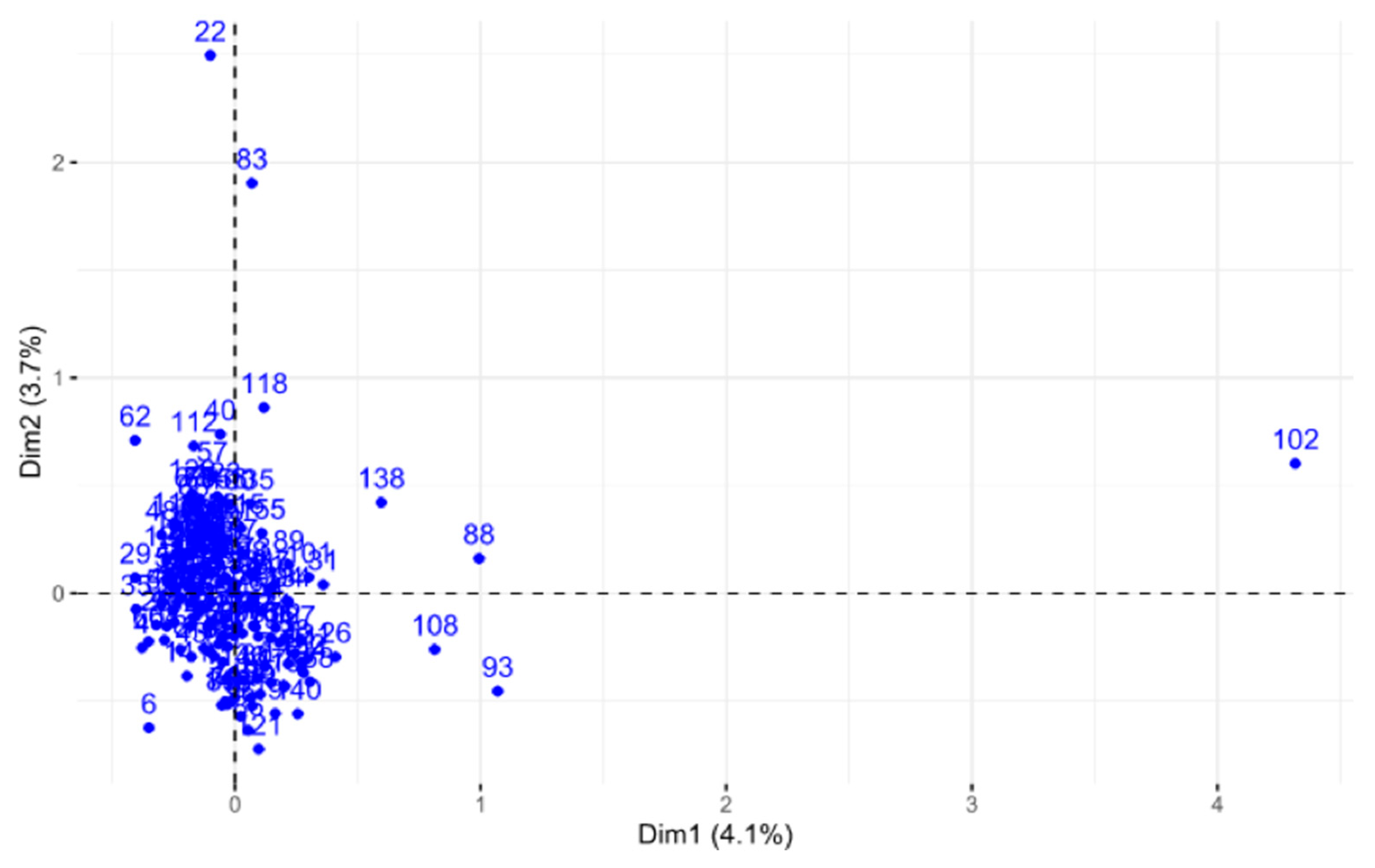

3.5. Multivariate Analysis

3.6. Local Sustainability Indicators

3.7. Vulnerability of Children and Implications for Children’s Health

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420); UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 9789211483185. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, J.H.P.; Friesen, J.; Taubenböck, H.; Wurm, M.; Pelz, P.F. The Unseen Population: Do We Underestimate Slum Dwellers in Cities of the Global South? Habitat Int. 2024, 148, 103056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulnaga, M.M.; Badran, M.F.; Barakat, M.M. Global Informal Settlements and Urban Slums in Cities and the Coverage. In Resilience of Informal Areas in Megacities—Magnitude, Challenges, and Policies; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, M. Challenges of Informal Urbanization. In Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG)); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-3-319-71061-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, S.S.; Gao, Q.; Shen, Q.; Kimirei, I.A.; Mapunda, D.W. Morphological Characteristics of Informal Settlements and Strategic Suggestions for Urban Sustainable Development in Tanzania: Dar Es Salaam, Mwanza, and Kigoma. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Poverty and Inequality: Enduring Features of an Urban Future? In World Cities Report 2022. Envisaging the Future of Cities; 2022; pp. 71–101. ISBN 978-92-1-133395-4. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Fink, G.; Günther, I.; Hill, K. Slum Residence and Child Health in Developing Countries. Demography 2014, 51, 1175–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat United Nations Human Settlements Programme Children, Cities, and Housing: Rights and Priorities. Available online: https://data.unhabitat.org/pages/publications (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- De Snyder, V.N.S.; Friel, S.; Fotso, J.C.; Khadr, Z.; Meresman, S.; Monge, P.; Patil-Deshmukh, A. Social Conditions and Urban Health Inequities: Realities, Challenges and Opportunities to Transform the Urban Landscape through Research and Action. J. Urban Health 2011, 88, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kim, R.; Subramanian, S.V. Economic-Related Inequalities in Child Health Interventions: An Analysis of 65 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 277, 113816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, P.; De Albuquerque, J.P.; Coaffee, J. The Impact of Urban Inequalities on Monitoring Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: Methodological Considerations. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto de Albuquerque, J.; Anderson, L.; Calvillo, N.; Coaffee, J.; Cunha, M.A.; Degrossi, L.C.; Dolif, G.; Horita, F.; Klonner, C.; Lima-Silva, F.; et al. The Role of Data in Transformations to Sustainability: A Critical Research Agenda. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 49, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat United Nations Human Settlements Programme. World Cities Report 2024: Cities and Climate Action. 2024. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/world-cities-report-2024-cities-and-climate-action (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Steiniger, S.; Wagemann, E.; de la Barrera, F.; Molinos-Senante, M.; Villegas, R.; de la Fuente, H.; Vives, A.; Arce, G.; Herrera, J.C.; Carrasco, J.A.; et al. Localising Urban Sustainability Indicators: The CEDEUS Indicator Set, and Lessons from an Expert-Driven Process. Cities 2020, 101, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.M.; Guedes Vidal, D.; Ferraz, M.P.; Cabeda, J.M.; Pontes, M.; Maia, R.L.; Calheiros, J.M.; Barreira, E. Measuring Health Vulnerability: An Interdisciplinary Indicator Applied to Mainland Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaco, M.; Díaz-Sánchez, J.P.; Lanchimba, C. Urban Primacy and Slum Prevalence in Latin American and Caribbean Countries in the 1990–2020 Period. Investig. Reg. J. Reg. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DANE. Patrones y Tendencias de La Transición Urbana En Colombia; DANE: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/poblacion/informes-estadisticas-sociodemograficas/2021-10-28-patrones-tendencias-de-transicion-urbana-en-colombia.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Costa-Caro, E. Demografía y Población. Available online: https://repository.unad.edu.co/bitstream/handle/10596/59242/necostac.pdf?sequence=1&is (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Romero-Murillo, P.; Gallego, J.L.; Leignel, V. Marine Pollution and Advances in Biomonitoring in Cartagena Bay in the Colombian Caribbean. Toxics 2023, 11, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saba, M.; Golondrino, G.E.C.; Torres-Gil, L.K. A Critical Assessment of the Current State and Governance of the UNESCO Cultural Heritage Site in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia. Heritage 2023, 6, 5442–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdelamar Villegas, F.F. Modernización Urbana y Exclusión Social En Cartagena de Indias, Una Mirada Desde La Prensa Local. Territorios 2017, 36, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Barrios, R.; Tirado-Ballestas, I.; Bertel-Sevilla, A.; Cervantes-Ceballos, L.; Gallego, J.L.; Leal, M.A.; Tovar, D.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Bioprospecting of Extremophilic Perchlorate-Reducing Bacteria: Report of Promising Bacillus Spp. Isolated from Sediments of the Bay of Cartagena, Colombia. Biodegradation 2024, 2024, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curren, R. Children of the Broken Heartlands: Rural Isolation and the Geography of Opportunity. Soc. Theory Pract. 2023, 49, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, L.; Cortés, L.F.T. Waste Pickers’ Formalisation from Bogotá to Cartagena de Indias: Dispossession and Socio-Economic Enclosures in Two Colombian Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bustamante, E.M.; Bohórquez-Moreno, C.E.; Severiche-Sierra, C. Social-Demographic and Health Conditions in Waste Pickers in the City of Cartagena de Indias (Colombia). Aglala 2018, 9, 430–442. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Atehortúa, M.T.; Arroyo Baena, C. Informalidad Urbana e Identidad Vecinal En Un Micromundo Gestado de Los Desechos de Una Ciudad: Barrio Henequén (1969–2001). Rev. Palobra “Palabra que Obra” 2014, 14, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Caro, N.E. Restaurando Dignidad Desde Lo Psicosocial En Los Recicladores Adultos Mayores Del Barrio Henequén de La Ciudad de Cartagena de Indias. 2023. Available online: https://repository.unad.edu.co/handle/10596/59242 (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Baun, D.L.; Christensen, T.H. Speciation of Heavy Metals in Landfill Leachate: A Review. Waste Manag. Res. 2004, 22, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, P.; Koliyabandara, P.A.; Cooray, A.T.; Lam, S.S.; Athapattu, B.C.; Vithanage, M. Progress and Prospects in Mitigation of Landfill Leachate Pollution: Risk, Pollution Potential, Treatment and Challenges. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubas, A.L.V.; Moecke, E.H.S.; Provin, A.P.; Dutra, A.R.D.A.; Machado, M.M.; Gouveia, I. Impacts of the Plastics From Waste Personal Protective Equipment in the COVID-19 Pandemic 2023. Polymers 2023, 15, 3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zam, R.I.F.; Sulistyaningsih, E.; Marchian, A.C.N. The Correlation between Bacteria and Parasite Patterns on Flies with Prevalence of Fly Vector-Borne Disease at the Market and the Landfill in Jember District, Indonesia. Medico-Legal Updat. 2020, 20, 491. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liao, W.; Li, G.; An, T. The Exposure Risks Associated with Pathogens and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Bioaerosol from Municipal Landfill and Surrounding Area. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 129, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andeobu, L.; Wibowo, S.; Grandhi, S. Informal E-Waste Recycling Practices and Environmental Pollution in Africa: What Is the Way Forward? Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 252, 114192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartini, N.; Jones, P. Urbanization and Urban Governance in Developing Countries. In Urban Book Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado-Montelongo, M.A. La Situación, Evolución y Composición de Las Familias Vulnerables y Su Socialización Primaria En Matamoros, Tamaulipas. Región Soc. 2016, 28, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, H.; Valera, C.M.; Rico, M.N. La Evolución de Las Estructuras Familiares En América Latina, 1990–2010: Los Retos de La Pobreza, La Vulnerabilidad y El Cuidado. 2014. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/36717-la-evolucion-estructuras-familiares-america-latina-1990-2010-retos-la-pobreza-la (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Torche, F.; Fletcher, J.; Brand, J.E. Disparate Effects of Disruptive Events on Children. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E.A.; Woessmann, L. Do Better Schools Lead to More Growth? Cognitive Skills, Economic Outcomes, and Causation. J. Econ. Growth 2012, 17, 267–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, B.; Filmer, D.; Patrinos, H.A. Making Schools Work: New Evidence on Accountability Reforms; Human Development Perspectives; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Goswami, S. Theoretical Framework for Assessing the Economic and Environmental Impact of Water Pollution: A Detailed Study on Sustainable Development of India. J. Futur. Sustain. 2024, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, P.; Peden, A.E.; Francis, K.L.; Cini, K.I.; Azzopardi, P.; Möller, H.; Ivers, R.Q. Interpersonal Violence and Gender Inequality in Adolescents: A Systematic Analysis of Global Burden of Disease Data from 1990 to 2019. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 74, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health; Krug, E.G., Dahlberg, L.L., Mercy, J.A., Zwi, A.B., Lozano, R., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fanslow, J.L.; Robinson, E.; Crengle, S.; Perese, L. Juxtaposing Beliefs and Reality: Prevalence Rates of Intimate Partner Violence and Attitudes to Violence and Gender Roles Reported by New Zealand Women. Violence Against Women 2008, 14, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjarres-Suarez, A.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Hematological Parameters and Hair Mercury Levels in Adolescents from the Colombian Caribbean. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 14216–14227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjarres-Suarez, A.; de la Rosa, J.; Gonzalez-Montes, A.; Galvis-Ballesteros, J.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Trace Elements, Peripheral Blood Film, and Gene Expression Status in Adolescents Living near an Industrial Area in the Colombian Caribbean Coastline. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2022, 32, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucros-Rodríguez, S.; Araque-Romany, F.; Montero-Mendoza, L.; Sarmiento-Nater, V.C.; Calvo-Carrillo, O.M.; Johnson-Restrepo, B.; Gallego, J.L.; Romero-Murillo, P. Analysis of Pollutant Accumulation in the Invasive Bivalve Perna Viridis: Current Status in the Colombian Caribbean 2020–2023. Toxics 2025, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranza-Lopez, L.; Alvarez-Ortega, N.; Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Gonzalez-Montes, A.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Biomonitoring of Lead Exposure in Children from Two Fishing Communities at Northern Colombia. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Ortega, N.; Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Low Blood Lead Levels Impair Intellectual and Hematological Function in Children from Cartagena, Caribbean Coast of Colombia. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2017, 44, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Ortega, N.; Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Toxicological Effects in Children Exposed to Lead: A Cross-Sectional Study at the Colombian Caribbean Coast. Environ. Int. 2019, 130, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartram, J.; Cairncross, S. Hygiene, Sanitation, and Water: Forgotten Foundations of Health. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Bartram, J.; Clasen, T.; Colford, J.M., Jr.; Cumming, O.; Curtis, V.; Bonjour, S.; Dangour, A.D.; De France, J.; Fewtrell, L.; et al. Burden of Disease from Inadequate Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Selected Adverse Health Outcomes: An Updated Analysis with a Focus on Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 221, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalberg Global Development Advisors. Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves: India Cookstoves and Fuels Market Assessment. 2013. Available online: https://projectgaia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/india-cookstove-and-fuels-market-assessment.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Ruiz-Garcia, A.; Arranz-Martínez, E.; Iturmendi-Martínez, N.; Fernández-Vicente, T.; Rivera-Teijido, M.; García-Álvarez, J.C. Tasas de Prevalencia de Enfermedad Renal Crónica y Su Asociación Con Factores Cardiometabólicos y Enfermedades Cardiovasculares. Estudio SIMETAP-ERC. Clínica Investig. Arterioscler. 2023, 35, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Barrera, B. Determinantes Sociales En Salud Que Influyen En Las Enfermedades Cardiovasculares En Personas de 18 Años y Más, Según Resultados de La Encuesta CASEN 2020. 2022. Available online: http://dspace.utalca.cl/bitstream/1950/13019/3/2022A000849.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- dos Prazeres Tavares, H.; Sachiteque, A.J.M.; Tavares, S.G.; Saiengue, F.M.; Sachiteque, A.C.; Kahuli, C.N.; Tavares, J.M.; Capingana, D.P.; Tavares, S.B.M.P. Family Planning: The Right Way to Avoid Perpetuating Poverty. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 13, 1831–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, V.C.C.; Higgins, J.; Logan, S.; Sheiham, A. Fluoride Toothpastes for Preventing Dental Caries in Children and Adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003, 2003, CD002278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, P.E. World Health Organization Global Policy for Improvement of Oral Health--World Health Assembly 2007. Int. Dent. J. 2008, 58, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, G.C.; Elani, H.W.; Harper, S.; Murray Thomson, W.; Ju, X.; Kawachi, I.; Kaufman, J.S.; Jamieson, L.M. Socioeconomic Status, Oral Health and Dental Disease in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Smith, A.G.C.; Bernabé, E.; Fleming, T.D.; Reynolds, A.E.; Vos, T.; Murray, C.J.L.; Marcenes, W.; Abyu, G.Y.; Alsharif, U.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence, Incidence, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for Oral Conditions for 195 Countries, 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maforah, F. The Impact of Poverty on Health in Urbanising Communities. J. Soc. Dev. Afr. 1994, 9, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sharan, P. Poverty and Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2007, 3, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royce, J.B. The Effects of Poverty on Childhood Development. J. Ment. Health Soc. Behav. JMHSB 2021, 3, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egba, N.A.; Ngwakwe, P.C. Impact of poverty on child health and development. J. Poverty Invest. Dev. 2015, 14, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Srivastava, P.; Singh, P.; Upadhyay, S.; Raghubanshi, A.S. Human Overpopulation and Food Security: Challenges for the Agriculture Sustainability. In Urban Agriculture and Food Systems: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 439–467. ISBN 9781522580645. [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone, M.J.; Chandna, J.; Kandawasvika, G.; Ntozini, R.; Majo, F.D.; Tavengwa, N.V.; Mbuya, M.N.N.; Mangwadu, G.T.; Chigumira, A.; Chasokela, C.M.; et al. Independent and Combined Effects of Improved Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) and Improved Complementary Feeding on Early Neurodevelopment among Children Born to HIV-Negative Mothers in Rural Zimbabwe: Substudy of a Cluster-Randomized Trial. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momberg, D.J.; Ngandu, B.C.; Voth-Gaeddert, L.E.; Cardoso Ribeiro, K.; May, J.; Norris, S.A.; Said-Mohamed, R. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) in Sub-Saharan Africa and Associations with Undernutrition, and Governance in Children under Five Years of Age: A Systematic Review. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2020, 12, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshida, H.A.; Kassim, N.; Mpolya, E.; Kimanya, M. Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Practices Associated with Nutritional Status of Under-Five Children in Semi-Pastoral Communities Tanzania. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyanda, A.E.; Adaralegbe, A.; Miranker, M.; Lasode, M.; Lu, Y. Housing Conditions as Predictors of Common Childhood Illness: Evidence from Nigeria Demographic and Health Surveys, 2008–2018. J. Child Health Care 2021, 25, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sustainable Development Goals | National Goal for 2030 | |

|---|---|---|

| Goal 1. End poverty in all its forms everywhere | By 2030, implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all and achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable. |

| By 2030, at least halve the proportion of men, women, and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions. | ||

| Goal 2. End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture | By 2030, end hunger and ensure access for all people, particularly the poor and the vulnerable, including children under one year, to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food all year round. |

| Goal 3. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages | By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least 12 per 1000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least 25 per 1000 live births. |

| By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services, including for family planning, information, and education, and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programs. | ||

| Goal 6. Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all | By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all. |

| By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations. | ||

| Goal 7. Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all | By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable, and modern energy services. |

| Goal 11. Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable | By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe, and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums. |

| Sustainable Development Goals | Indicator | Target for 2030 | Local Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goal 1. End poverty in all its forms everywhere | Proportion of the population covered by systems or minimum levels of social protection | 100% | 96.2% |

| Proportion of men, women, and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions, according to national definitions | 8.4% | 81.6% | |

| Goal 2. End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture | Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity | 0% | 24.7% |

| Goal 3. Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages | Child mortality rate (for 1000) | 0.012 | 0.032 |

| Proportion of women of reproductive age who meet their family planning needs with modern methods | 100% | 17.7% | |

| Goal 6. Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all | Proportion of the population using drinking water supply services | 100% | 82.9% |

| Proportion of the population using risk-managed sanitation services | 100% | 50.6% | |

| Goal 7. Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all | Proportion of the population with access to electricity | 100% | 100% |

| Goal 11. Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable | Proportion of the urban population living in inadequate housing | 0% | 93.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tirado-Ballestas, I.P.; Gallego, J.L.; Zuluaga-Ortiz, R.; Roa-Pérez, V.; Silva-Cortés, A.; Sarmiento, M.C.; De la Hoz-Domínguez, E.J. Integrating Socio-Demographic and Local Sustainability Indicators: Implications for Urban Health and Children’s Vulnerability in Henequén Neighborhood in Cartagena, Colombia. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060220

Tirado-Ballestas IP, Gallego JL, Zuluaga-Ortiz R, Roa-Pérez V, Silva-Cortés A, Sarmiento MC, De la Hoz-Domínguez EJ. Integrating Socio-Demographic and Local Sustainability Indicators: Implications for Urban Health and Children’s Vulnerability in Henequén Neighborhood in Cartagena, Colombia. Urban Science. 2025; 9(6):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060220

Chicago/Turabian StyleTirado-Ballestas, Irina P., Jorge L. Gallego, Rohemi Zuluaga-Ortiz, Vladimir Roa-Pérez, Alejandro Silva-Cortés, María C. Sarmiento, and Enrique J. De la Hoz-Domínguez. 2025. "Integrating Socio-Demographic and Local Sustainability Indicators: Implications for Urban Health and Children’s Vulnerability in Henequén Neighborhood in Cartagena, Colombia" Urban Science 9, no. 6: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060220

APA StyleTirado-Ballestas, I. P., Gallego, J. L., Zuluaga-Ortiz, R., Roa-Pérez, V., Silva-Cortés, A., Sarmiento, M. C., & De la Hoz-Domínguez, E. J. (2025). Integrating Socio-Demographic and Local Sustainability Indicators: Implications for Urban Health and Children’s Vulnerability in Henequén Neighborhood in Cartagena, Colombia. Urban Science, 9(6), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060220