Normative Pluralism and Socio-Environmental Vulnerability in Cameroon: A Literature Review of Urban Land Policy Issues and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

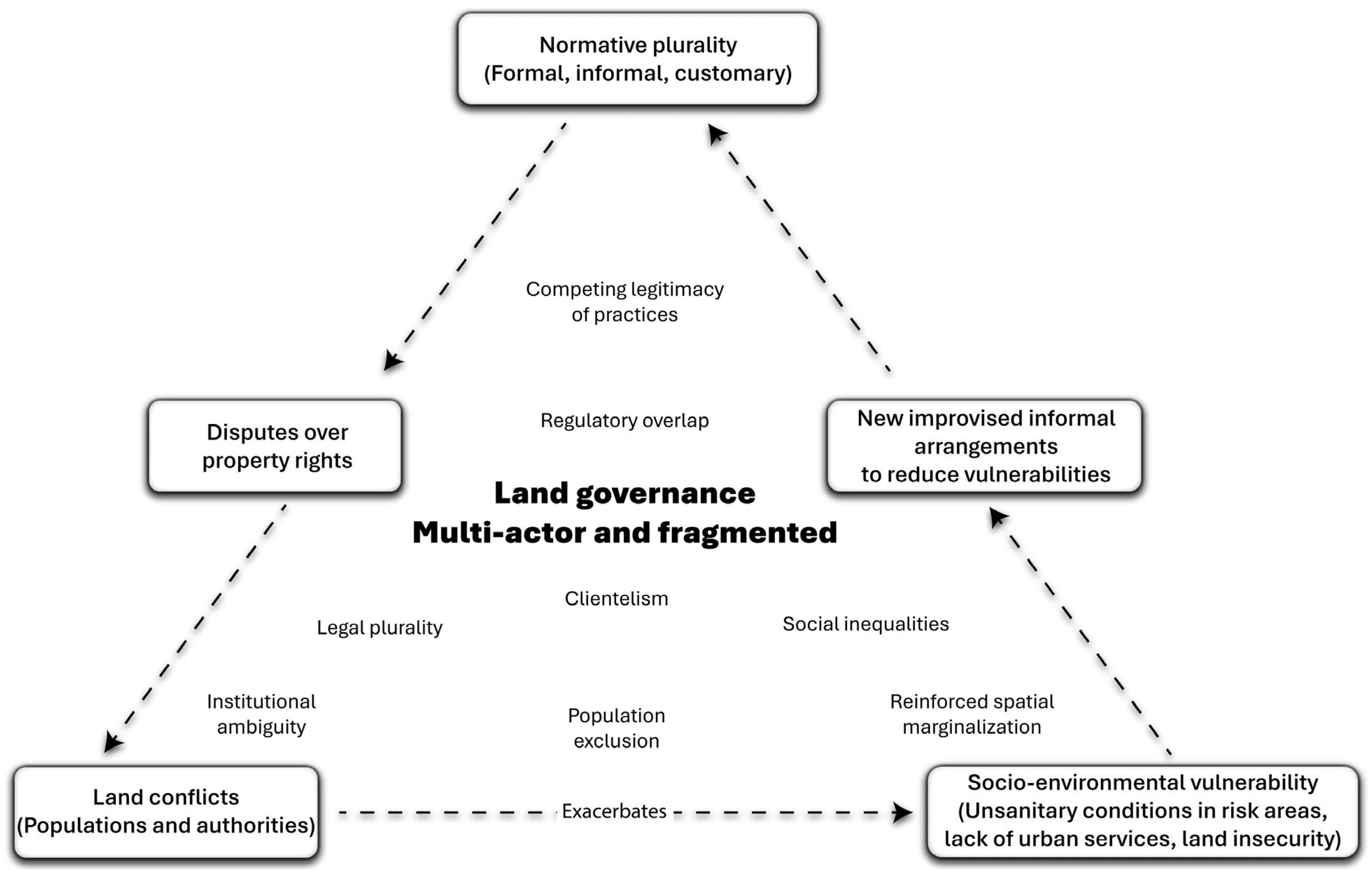

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Interconnections Between Normative Plurality and Land Governance in African Cities

2.2. Socio-Environmental Vulnerability of Populations

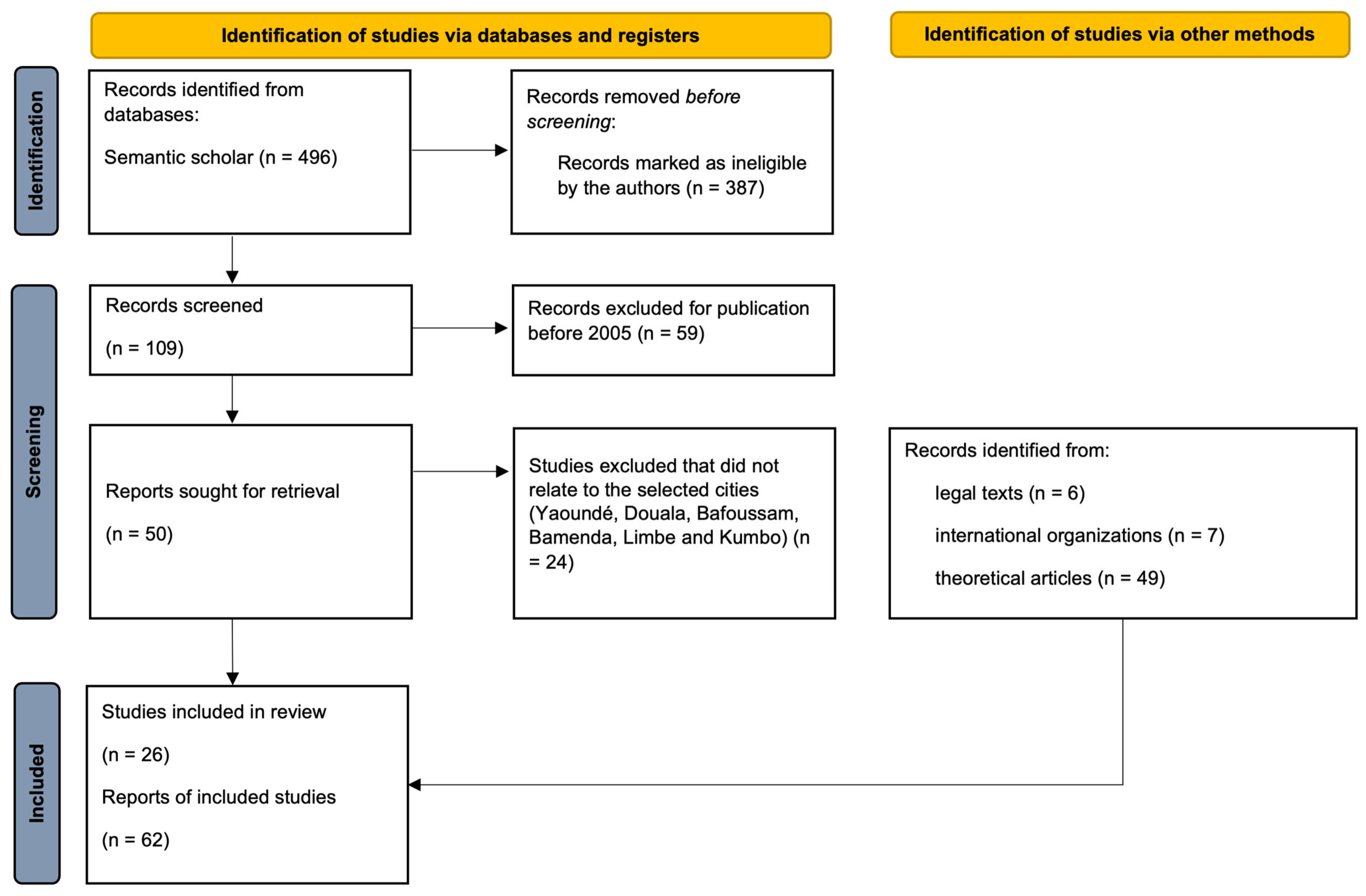

3. Method for the Systematic Review of the Literature on the Issues and Challenges of Urban Land in Cameroon

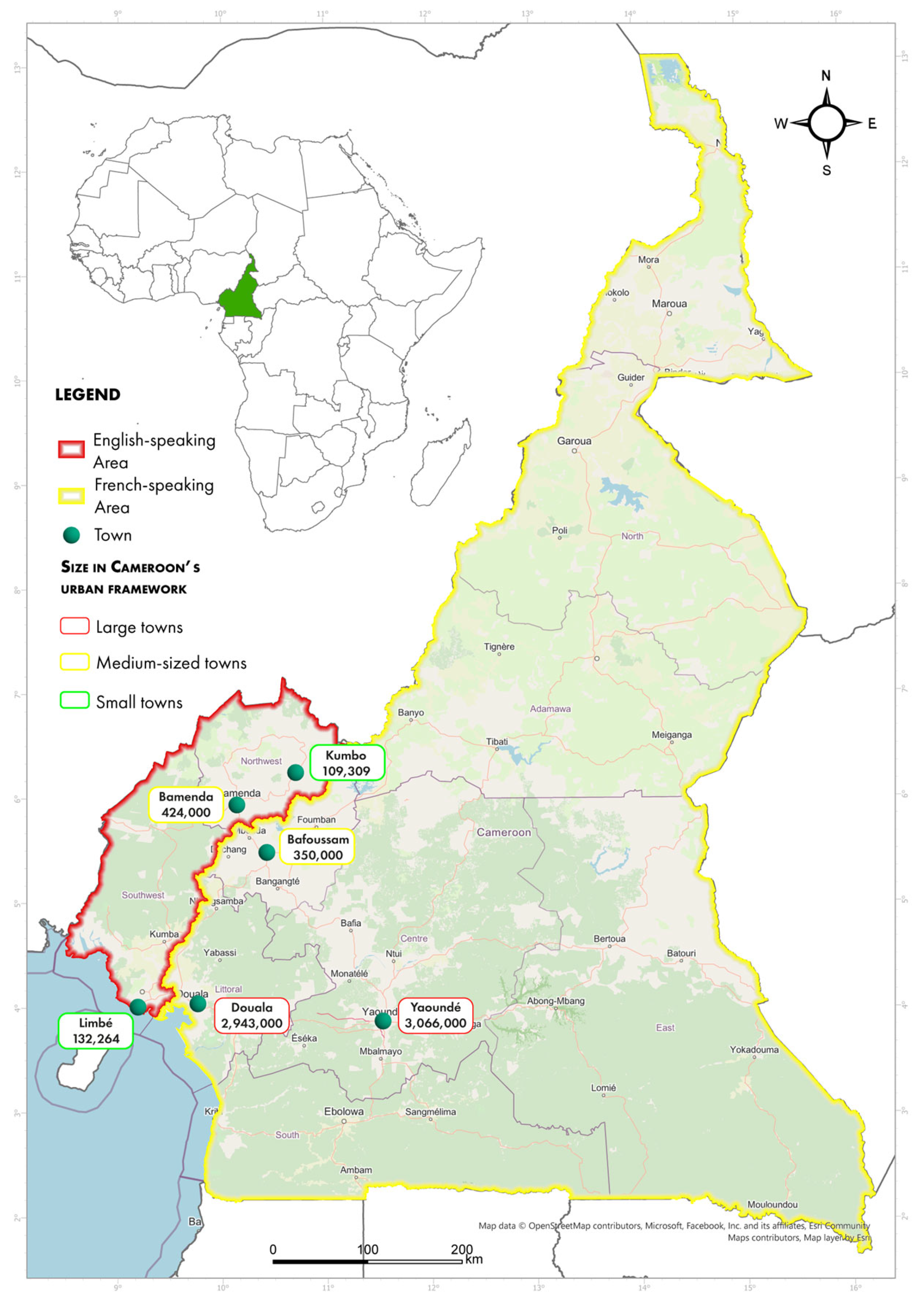

4. Cameroonian Cities: A Landscape Marked by Tensions Between Two Land Systems

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Formal Framework for Urban Land Governance in Cameroon

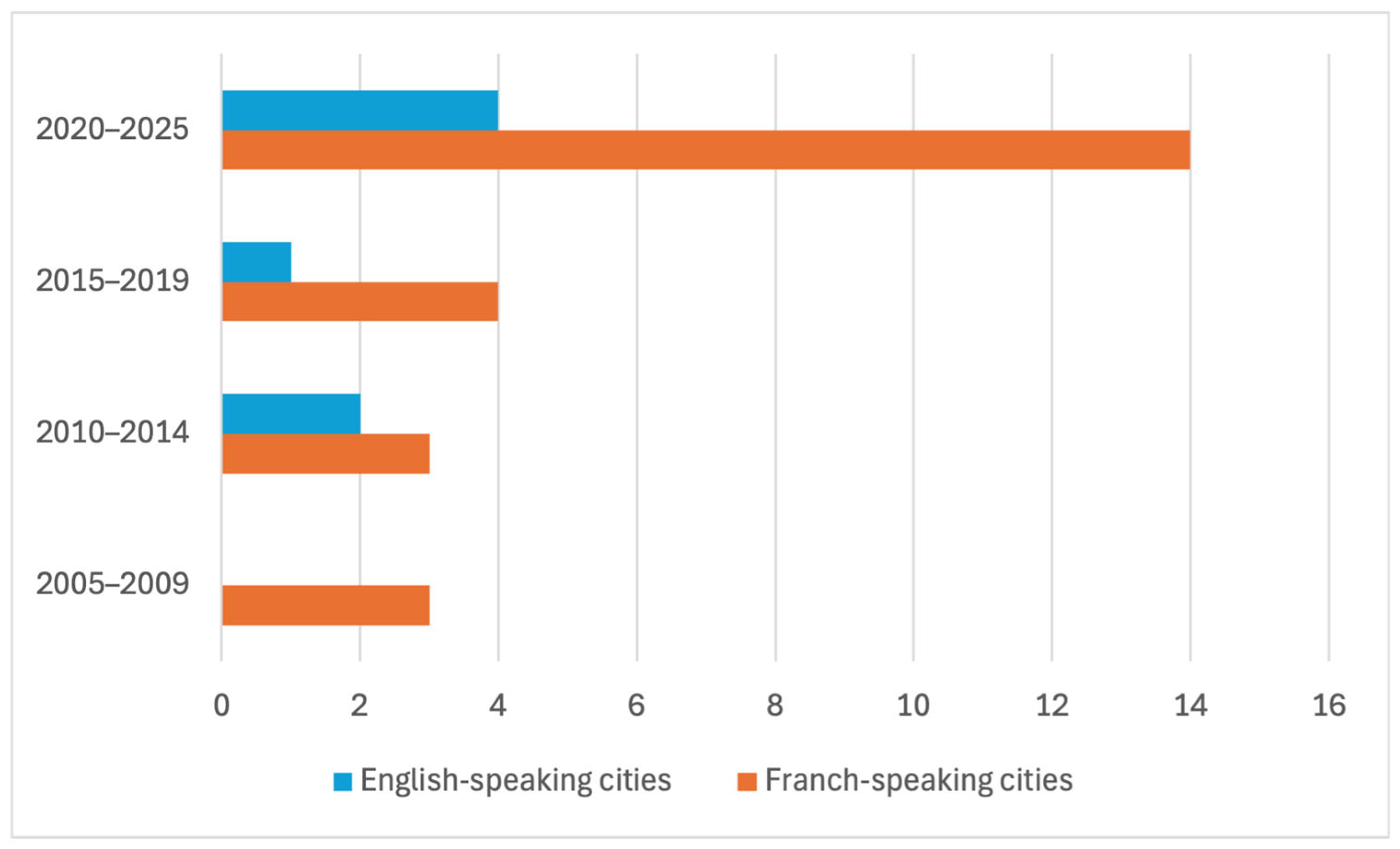

5.2. Analysis of Land Dynamics in Cameroonian Cities Based on Colonial Legacies, the Legal System, and the Linguistic Zone

5.3. Analysis of Land Dynamics in Cameroonian Cities According to the Size of the City

5.3.1. Similar Dynamics: A Normative Dualism Between Formal and Informal Norms

5.3.2. Divergent Dynamics: Contrasting Socio-Environmental Challenges

Land Pressure and Environmental Risks

Social Tensions and Land Conflicts

Institutional Regulatory Mechanisms

5.3.3. Summary of Land Dynamics in Urban Areas in Cameroon

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nations Unies. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210042352 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Smit, W. Urban Governance in Africa: An Overview. In African Cities and the Development Conundrum; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wily, L.A. ‘The Law is to Blame’: The Vulnerable Status of Common Property Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa. Dev. Change 2011, 42, 733–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home, R. History and Prospects for African Land Governance: Institutions, Technology and ‘Land Rights for All’. Land 2021, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigbu, U.E. The Quest for “Good Governance” of Urban Land in Sub-Saharan Africa: Insight into Windhoek, Namibia. In Land Issues for Urban Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa; Home, R., Ed.; Local and Urban Governance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 17–34. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-52504-0_2 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Bhanye, J. Beyond informality: ‘Nimble peri-urban land transactions’—How migrants on the margins trade, access and hold land for settlement. Discov. Glob. Soc. 2024, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchzermeyer, M. Cities with ‘Slums’: From Informal Settlement Eradication to a Right to the City in Africa. Juta and Company Ltd.: Sandton, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, S. 1—Land in the Political Economy of African Development: Alternative Strategies for Reform. Afr. Dev. 2007, 32. Available online: https://journals.codesria.org/index.php/ad/article/view/1086 (accessed on 2 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K.S.; Ubink, J.M. Contesting Land and Custom in Ghana. State, Chief and the Citizen; Leiden University Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008; Available online: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/32871 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Mabogunje, A. Perspective on Urban Land and Urban Management Policies in Sub-Saharan Africa. 1992. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Perspective-on-Urban-Land-and-Urban-Management-in-Mabogunje/d23cf8def6ed3bc3ebe72eb7d77463c0084d0561 (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Pinard, E. The Consolidation of ‘Traditional Villages’ in Pikine, Senegal: Negotiating Legitimacy, Control and Access to Peri-Urban Land. Afr. Stud. 2021, 80, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamba, N.N. Le Genre et la Gouvernance Foncière en Afrique Subsaharienne Analysés Suivant L’approche du «Système hybride». Ph.D. Thesis, Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10393/43359 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Minfede, R.K. Imperfection des marchés fonciers urbains et transactions foncières in formelles au Cameroun. Rev. D Econ. Reg. Urbaine 2025, 5b–23b. [Google Scholar]

- Nyuykighanse, N.E.; Yenlajai, B.J.; Fru, C.F.; Kimengsi, J.N. Land Use Conflicts and Planning Implications: Insights from Kumbo, Cameroon. J. Geogr. Environ. Earth Sci. Int. 2023, 27, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abass, K.; Buor, D.; Afriyie, K.; Dumedah, G.; Segbefi, A.Y.; Guodaar, L.; Garsonu, E.K.; Adu-Gyamfi, S.; Forkuor, D.; Ofosu, A.; et al. Urban sprawl and green space depletion: Implications for flood incidence in Kumasi, Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizelis, T.-I.; Pickering, S.; Urdal, H. Conflict on the urban fringe: Urbanization, environmental stress, and urban unrest in Africa. Political Geogr. 2021, 86, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. Kenya. la Vie de L’autre Moitié de la Population. Les Habitants des Bidonvilles de Nairobi (Kenya). 2009. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/fr/documents/afr32/006/2009/fr/ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Bignon, C. Légitimités Citadines et Pratiques Foncières à Douala. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France, 2018. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-02280082 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data. 2024. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Akoh, N.R. The Nexus between Land registration and Environmental Hazards in some Urban Centers in Cameroon. Br. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaha, J.P. Mutations socio-économiques et recompositions territoriales dans un espace géographique à l’ombre de Douala: Le Bas-Moungo/Bas-Wouri (Cameroun). Rev. Géogr. Cameroun 2006, 17–18, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Chauveau, J.P.; Le Pape, M.; Olivier de Sardan, J.P. La pluralité des normes et leurs dynamiques en Afrique. In Inégalités Polit Publiques En Afr Plur Normes Jeux Acteurs; Paris Karthala: Paris, France, 2001; pp. 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, C. Twilight Institutions: Public Authority and Local Politics in Africa. Dev. Change 2006, 37, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C. Propriété et Citoyenneté Dans L’afrique des Villes; Karthala Editions: Paris, France, 2013; 220p. [Google Scholar]

- Enemark, S.; McLaren, R.; van der Molen, P. Land governance in support of the millennium development goals: A new agenda for land professionalss. In Proceedings of the XXIV FIG International Congress 2010 «Facing the Challenges: Building the Capacity», Sydney, Australia, 11–16 April 2010; International Federation of Surveyors (FIG): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; p. 4662. Available online: https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/land-governance-in-support-of-the-millennium-development-goals-a- (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Deininger, K.; Selod, H.; Burns, A. The Land Governance Assessment Framework: Identifying and Monitoring Good Practice in the Land Sector; World Bank Publication: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=rYCipEVWF-kC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Deininger,+K.;+et+al.+(2011).+The+land+governance+assessment+framework:+Identifying+and+monitoring+good+practice+in+the+land+sector.+The+World+Bank.&ots=4JCgDFCOyZ&sig=5xJ1oCcjvXtAWvSjbI9dOKolEW8 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Simeu-Kamdem, M.; Touna Mama, E. Les Politiques de la Ville en Question: À la Recherche D’une Meilleure Gouvernance Urbaine en Afrique Subsaharienne; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 1–296. [Google Scholar]

- Abbink, G.J.; De Bruijn, M. Land, Law and Politics in Africa Mediating Conflict and Reshaping the State; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011; 386p. [Google Scholar]

- Platteau, J. Allocating and Enforcing Property Rights in Land: Informal versus Formal Mechanisms in Subsaharan Africa. Nord. J. Political Econ. 2000, 26, 55–81. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Allocating-and-Enforcing-Property-Rights-in-Land%3A-Platteau/aab55d32da2f70eaaf6ed83b1dbb4a7ca42bd856 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Chindji, R.M. Problématique foncière relative à l’occupation de l’espace autour des monts mbankolo et akok-ndoué à yaoundé. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospat. Sci. 2021, 4, 552–570. [Google Scholar]

- Choplin, A. Le foncier urbain en Afrique: Entre informel et rationnel, l’exemple de Nouakchott (Mauritanie). Ann. Géogr. 2006, 647, 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Agegnehu, S.K.; Dires, T.; Nega, W.; Mansberger, R. Land Tenure Disputes and Resolution Mechanisms: Evidence from Peri-Urban and Nearby Rural Kebeles of Debre Markos Town, Ethiopia. Land 2021, 10, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choplin, A.; Dessie, E. Titling the desert: Land formalization and tenure (in)security in Nouakchott (Mauritania). Habitat Int. 2017, 64, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Galès, P.; Vitale, T. Governing the Large Metropolis. A Research Agenda; Sciences Po: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B.L.; Kasperson, R.E.; Matson, P.A.; McCarthy, J.J.; Corell, R.W.; Christensen, L.; Eckley, N.; Kasperson, J.X.; Luers, A.; Martello, M.L.; et al. A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8074–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.; Enemark, S.; van der Molen, P. Climate resilient urban development: Why responsible land governance is important. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristide, E.E. Urban Spaces Resettlement Policies in Yaounde: «Forced» Evictions? Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1654155 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009325844/type/book (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Zerbo, A.; Delgado, R.C.; González, P.A. Vulnerability and everyday health risks of urban informal settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Health J. 2020, 4, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Mitchell, M.I. Revisiting the World Bank’s land law reform agenda in Africa: The promise and perils of customary practices. J. Agrar. Change 2018, 18, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitonge, H. Land Governance in Africa: The New Policy Reform Agenda. In Land Tenure Challenges in Africa: Confronting the Land Governance Deficit; Chitonge, H., Harvey, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K.; Land Governance in Africa. Hist Context Has Shaped Key Contemp. 2012. Available online: https://d3o3cb4w253x5q.cloudfront.net/media/documents/FramingtheDebateLandGovernanceAfrica.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Madumere, N. Customary Land Rights and Gender Justice in Eastern Nigeria and Ghana. Ph.D. Thesis, University of East London, London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orock, R.T. The indigene-settler divide, modernisation and the land question: Indications for social (dis) order in Cameroon. Nord. J. Afr. Stud. 2005, 14, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng-Odoom, F. Urban Governance in Africa Today: Reframing, Experiences, and Lessons. Growth Change 2017, 48, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; 376p. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touoyem, F.M.; Binele, M.S.K. Local communities face to land expropriation and evictions in the era of major structural projects and territorial regulation in Southern Ca meroon: An analysis of the outlines of a controversial phenomenon. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospat. Sci. 2020, 3, 48–67. Available online: https://revues.imist.ma/index.php/AJLP-GS/article/view/18068 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- N’nde, P.B.; Talla, G.S. Informalité, appropriation populaire et projection d’espaces urbains sécurisés. GARI-Rech. Débats Villes Afr. 2021, 1, 129–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdam-Boutin, M. Restructuration scalaire et néolibéralisation des politiques publiques de logement au Cameroun: Éprouver la théorie du réétalonnage scalair e dans un contexte autoritaire. Métropoles 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand-Lasserve, A. La Question Foncière Dans Les Villes du Tiers-Monde: Un Bilan. 2004. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/La-question-fonci%C3%A8re-dans-les-villes-du-Tiers-monde-Durand-Lasserve/9b7c5d1cb773cf13c6c05332fa134c04689e7c28 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- UN-Habitat. Note de Politique Urbaine Nationale du Cameroun; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; p. 36. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/20161129_NOTE%20Synthetique%20de%20PNU-Cameroun.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Nnomenko’o, J. La problématique du statut de la propriété foncière coutumière au Came roun. NGABAN-DIBOLEL 2021, 2, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, N.S. Land Ownership in Cameroon: An Overview. Int. J. Law Policy 2023, 8, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonjong, L.; Sama-Lang, I.; Fon, F.L. An Assessment of the Evolution of Land Tenure System in Cameroon and its Effects on Women’s Land Rights and Food Security. Perspect. Glob. Dev. Technol. 2010, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin, E.K.; Munisi, S.; Kuoribo, E.; Kiwanuka, A.; Thiedeitz, M.; Mohamed, F. Urbanization and Urban Sprawl in the Post-Colonial Era Douala City, Cameroon. Tanzan. J. Eng. Technol. 2024, 43, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguiffo, S.A. Améliorer le système d’expropriation et de compensation dans un contex te de pluralisme juridique: Leçons du Camerou. Afr. J. Land Policy Geospat. Sci. 2020, 3, 53–67. Available online: https://revues.imist.ma/index.php/AJLP-GS/article/view/18335 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Fredriksson, P.G.; Gupta, S.K.; Zhao, W.; Wollscheid, J.R. Legal heritage and urban slums. J. Reg. Sci. 2023, 63, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoh, A.J. Planning in Contemporary Africa: The State, Town Planning and Society in Cameroon; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; 324p. [Google Scholar]

- Njoh, A.J. Equity, Fairness and Justice Implications of Land Tenure Formalization in Cameroon. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 750–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- République du Cameroun. Ordonnance Fixant le Régime Domanial. 1974; p. 5. Available online: https://www.cvuc-uccc.com/minat/textes/35.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- République du Cameroun. Décret Fixant les modalités de gestion du Domaine National, 76-166; 1976; p. 5. Available online: https://yaounde.eregulations.org/media/D%C3%A9cret%2076-166%20au%2027%20avril%201976%20fixant%20les%20modalit%C3%A9s%20de%20gestion%20du%20domaine%20national.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Renz, T.T. Urban Land Grabbing Mayhem in Douala Metropolitan Local Council Areas, Cameroon. Curr. Urban Stud. 2018, 6, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- République du Cameroun. Loi Relative à L’expropriation Pour Cause D’utilité Publique et Aux Modalités D’indemnisation. 1985; p. 3. Available online: https://www.cvuc-uccc.com/minat/textes/28.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Socpa, A. New kinds of land conflict in urban Cameroon: The case of the «landless» indigenous peoples in Yaoundé. Afr. J. Int. Afr. Inst. 2010, 80, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoul, M.K. Informal land transactions and demolition of houses in Cameroon. Hous. Stud. 2024, 39, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- République du Cameroun. Loi Portant Orientation de la Décentralisation. 2004/017. 2004; p. 13. Available online: https://www.cvuc-uccc.com/minat/textes/13.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- République du Cameroun. Loi Régissant L’urbanisme Au Cameroun. 2004-003. 2004; p. 24. Available online: https://douala.eregulations.org/media/loi_urbanisme_cameroun.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Maluh, N.B. Urban Housing Practices of Policy Implementation in Bamenda, Cameroon. Urban Reg. Plan. 2024, 9, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenji, M.J.; Neba, W.S. Land Tenure Practices and Substandard Housing in Bamenda Urban, Northw est Cameroon. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Invent. 2025, 12, 8409–8428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kometa, C.G.; Asongsaigha, R.N. The Implications of Land Tenure Systems on Socio-Economic Development in Kumbo Central Sub-Division, North West Region of Cameroon. J. Geogr. Geol. 2019, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Awah, Y.L. Diagnosing the Urban Expansion-Land Conflict Nexus in Bamenda II, Cameroon. J. Geogr. Environ. Earth Sci. Int. 2021, 25, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Douala 3 Spatial Profile—Cameroon; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Douala, Cameroon, 2024; p. 200. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/douala-3-spatial-profile-cameroon (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Morenas, M.; Grelet, L.; Wood, D.; Heudjeu, F. Comprendre et Quantifier le Marchè Locatif au Cameroun; Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa (CAHF): Johannesburg, South Africa, 2021; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, C.; Bonnassieux, A. Quelles politiques publiques pour les quartiers irréguliers des villes africaines? Entre lotissement et laisser-faire. Le cas de Ouagadougou au Burkina Faso. Ann. Géogr. 2021, 738, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M. Une Afrique des Convoitises Foncières: Regards Croisés Depuis le Mali; Presses universitaires du Midi: Toulouse, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Socpa, A. Bailleurs Autochtones et Locataires Allogènes: Enjeu Foncier et Partic ipation Politique au Cameroun. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2006, 49, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiafack, O.; Mbon, A.M. Urban Growth and Front Development on Risk Zones: GIS Application for Mapping of Impacts on Yaounde North Western Highlands, Cameroon. Curr. Urban Stud. 2017, 05, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tende, R.T.; Kengmoe, E.T. Urban overspill and its upshot to the Bafoussam Emergent Metropolis in Cameroon. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 7, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguh, B.S. Land tenure and land use dynamics in Limbe City, South West Region of Cameroon. Agric. Sci. Dev. 2013, 2, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pemunta, N.V. New forms of land enclosures: Multinationals and state production of territory in cameroon. Stud. Univ. Babes-Bolyai Sociol. 2014, 59, 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ondoua, P.D.B. Suspecting Change in Cameroon: Slums Improvement and the Logics of Belonging in Yaoundé. Afr. Rev. 2024, 1, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Njoh, A.J.; Ananga, E.O.; Anchang, J.Y.; Ayuk-Etang, E.M.; Akiwumi, F.A. Africa’s triple heritage, land commodification and women’s access to land: Lessons from Cameroon, Kenya and Sierra Leone. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2017, 52, 760–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaligot, R.; Kemajou, A.; Chenal, J. Cultural ecosystem services provision in response to urbanization in Cameroon. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essougong, U.P.K.; Teguia, S.J.M. How secure are land rights in Cameroon? A review of the evolution of land tenure system and its implications on tenure security and rural livelihoods. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home, R. Land dispute resolution and the right to development in Africa. J. Jurid. Sci. 2020, 45, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndegue, S.G.B. Dynamiques foncières, ethnocratie et défi de l’intégration ethnocultur elle au Cameroun. Anthropol. Soc. 2019, 43, 211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Tafon, R.; Saunders, F. The Politics of Land Grabbing: State and corporate power and the (tran s)nationalization of resistance in Cameroon. J. Agrar. Change 2018, 19, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbuagbo, O.T. Cameroon: Flawed decentralization and the politics of identity in the urban space. Glob. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2012, 12, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Marrengane, N.; Croese, S. (Eds.) Reframing the Urban Challenge in Africa: Knowledge Co-Production from the South; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; 222p. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.S.; Di Gregorio, M.; Meinzen-Dick, R.S.; Di Gregorio, M. Collective Action and Property Rights for Sustainable Development. 2004. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/16031 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Vitale, T. Regulation by Incentives, Regulation of the Incentives in Urban Policies. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2010, 2, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, A.; Angel, S. Global Monitoring with the Atlas of Urban Expansion. In Urban Remote Sensing; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 247–282. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781119625865.ch12 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

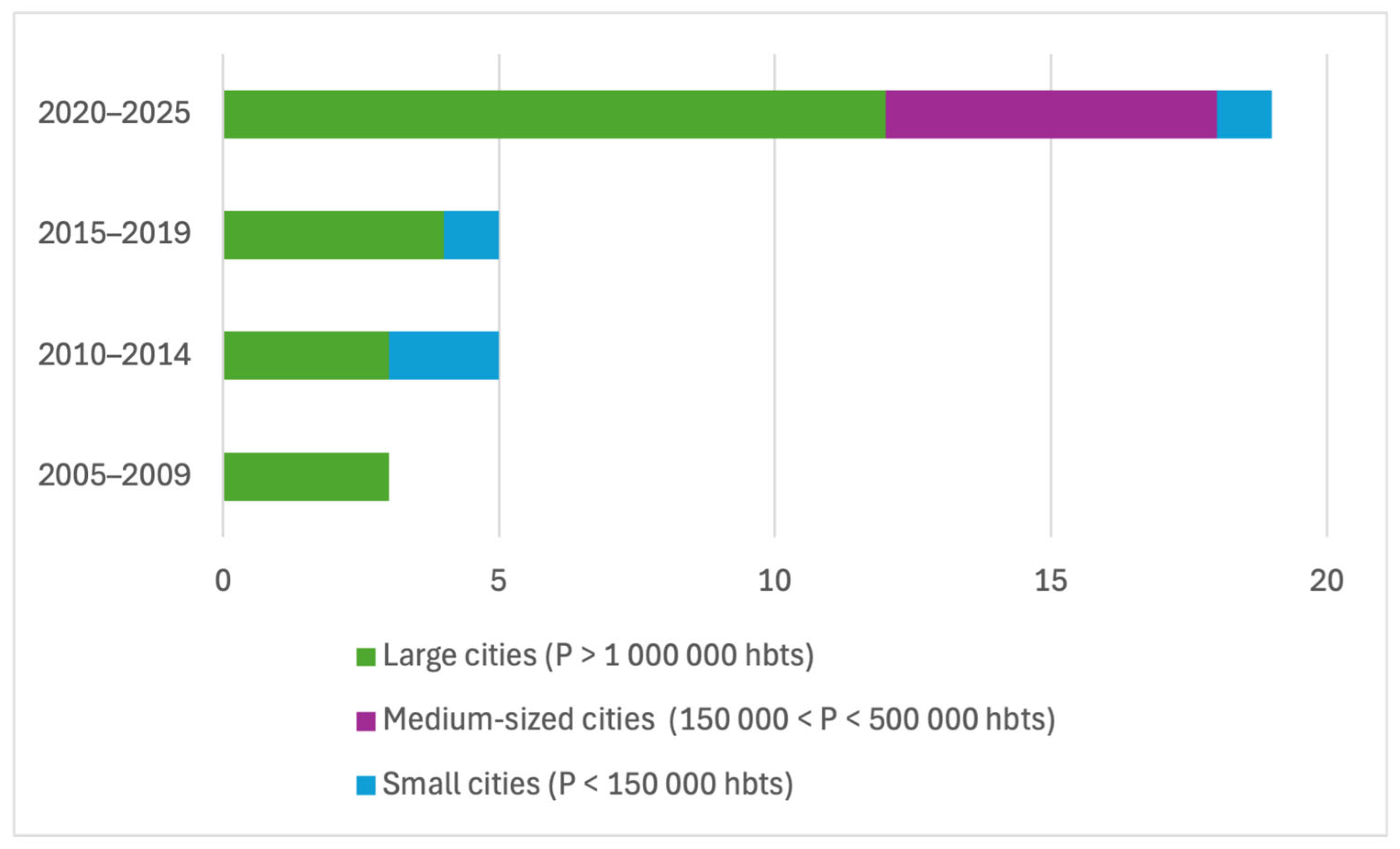

| Large Cities [p > 1,000,000 Inhabitants] | Medium-Sized Towns [150,000 < p < 500,000 Inhabitants] | Small Towns [p < 150,000 Inhabitants] | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yaounde | Douala | Bafoussam | Bamenda | Limbe | Kumbo | ||

| 2005–2009 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 2010–2014 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |||

| 2015–2019 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |||

| 2020–2025 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 19 | |

| Total | 11 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 32 |

| Text and Laws | Description and Application of the Legal Land Framework in Urban Areas in Cameroon |

|---|---|

| Order No. 74-1 and 2 of July 6 1974 [62], which establishes the land and property regime | Constituting the backbone of the legal framework for land in Cameroon, this text aims to regularize and secure land ownership through the allocation of land titles. It imposes a 25 m easement around risk areas and classifies them in the public domain of the state. On the ground, these ecologically sensitive spaces find themselves occupied by populations [20]. The application of this text is then compromised by limited resources of local authorities and ineffective governance [61]. |

| Decree No. 76–166 of April 27 1976 [63] sets the terms of management of land in Cameroon | This decree regulates the procedures for registering and organizing consultative commissions for the settlement of land disputes. It defines land registration procedures and clarifies the distinctions between different types of land: private land, national domain land, and public and private state domain land. Cadastral authorities can use this text to regularize occupations according to political and economic interests, thus favoring certain actors over vulnerable populations [64]. This perception is exacerbated by the initial centralization of the procedure at the Ministry of Lands, Cadastre and Land Affairs (MINCAF), now decentralized to the level of the prefectures, where a lack of communication and transparency remains problematic [43]. |

| Law on expropriation for public utility and compensation arrangements 1985 [65] | Article 3.1 of this decree provides for compensation provisions. As such, no compensation is provided for populations occupying marshland areas. Although this law is designed to secure transactions for the benefit of public services, it is often criticized for its complex and formal procedures which, far from guaranteeing fair compensation, generate a feeling of injustice among the affected populations [66]. Also, some political actors sometimes use the argument of public utility to justify land reallocation, without necessarily respecting the legal compensation procedures [58,67]. |

| Law No. 2004/017 of July 22 2004 [68] on decentralization | By redefining the roles of the actors involved in land management, this law transfers to decentralized local authorities [municipalities and urban communities] certain key skills in planning and regulating land use. Thus, the Ministry of State Property, Cadastre and Land Affairs (MINCAF) and its delegations remain responsible for regulating the national cadastre, as well as issuing land titles, while decentralized local authorities now control urban development through the preparation of urban planning documents, urban planning operations, and the granting of building permits [60]. |

| Law No. 2004/003 of April 21 2004 [69], which governs urban planning in Cameroon | This law governs the general rules of urban planning and the construction standards necessary for the preparation of urban planning documents and the obtaining of various urban planning acts (building permits, certificates of conformity, etc.). “These instruments have not been appropriate to avoid the problems of proliferation of shanty towns and the sprawl of cities” [53]. |

| Urban planning documents and urban planning operations | The Urban Master Plans (PDU) and Land Use Plans (POS), resulting from the 2004 Urban Planning Act, are essential urban planning documents, drawn up by decentralized local authorities (urban communities and district municipalities) to define the main development guidelines. These plans manage urban expansion and protect land against inappropriate uses, while defining non-buildable zones in collaboration with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (MINHDU). They prohibit the occupation of risk zones, some of which are located on land belonging to customary communities. These plans are criticized for their regulatory weakness in implementation and their inability to regulate urbanization [53,70]. |

| Land Standards | Land Conflicts | Land Pressures | Institutional Regulation | Environmental Risks | Proposed Governance Solutions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large cities (Yaoundé, Douala) | Cohabitation with a domination of formal norms | Competition between actors for land control | Very strong [migration, major projects] | Strong state centralization, but informal regulation exists | Strong [marshy areas and hills at risk] | Decentralization of certain land powers to metropolitan authorities, digitization of registers, multi-stakeholder consultation prior to setting up structuring projects, and granting of provisional occupancy titles to informal populations. |

| Medium-sized towns (Bamenda, Bafoussam) | Balanced cohabitation between formal and customary norms | Urban expansion and incompatibility of uses | Medium to high [peri-urban expansion] | Balanced between formal regulation and customary regulation | Medium to high [exposed peri-urban areas] | Integration of customary authorities into urban planning processes, clarification of communal and customary power boundaries, and strengthening of land mediation mechanisms. |

| Small towns (Limbe, Kumbo) | Strong dominance of customary norms | Conflicts over customary agricultural land | Moderate except in Limbe [tourist and industrial pressure] | Regulation dominated by customary chiefdoms | Low to medium [erosion and coastal pressure in Limbe] | Local codification of customary land use, legal recognition of chiefdoms, and land use plans drawn up in consultation with local stakeholders. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bah, I.; Teguia Kenmegne, R.L. Normative Pluralism and Socio-Environmental Vulnerability in Cameroon: A Literature Review of Urban Land Policy Issues and Challenges. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060219

Bah I, Teguia Kenmegne RL. Normative Pluralism and Socio-Environmental Vulnerability in Cameroon: A Literature Review of Urban Land Policy Issues and Challenges. Urban Science. 2025; 9(6):219. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060219

Chicago/Turabian StyleBah, Idiatou, and Roussel Lalande Teguia Kenmegne. 2025. "Normative Pluralism and Socio-Environmental Vulnerability in Cameroon: A Literature Review of Urban Land Policy Issues and Challenges" Urban Science 9, no. 6: 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060219

APA StyleBah, I., & Teguia Kenmegne, R. L. (2025). Normative Pluralism and Socio-Environmental Vulnerability in Cameroon: A Literature Review of Urban Land Policy Issues and Challenges. Urban Science, 9(6), 219. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060219