Transport and Wellbeing of Public Housing Tenants—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Public Housing and Urban Regeneration Wellbeing Frameworks

1.1.1. General Wellbeing Framework

1.1.2. Māori Wellbeing Model

1.1.3. Principles Underpinning Pacific Worldviews: Insights into Wellbeing

1.1.4. Application of the Wellbeing Frameworks to Transport

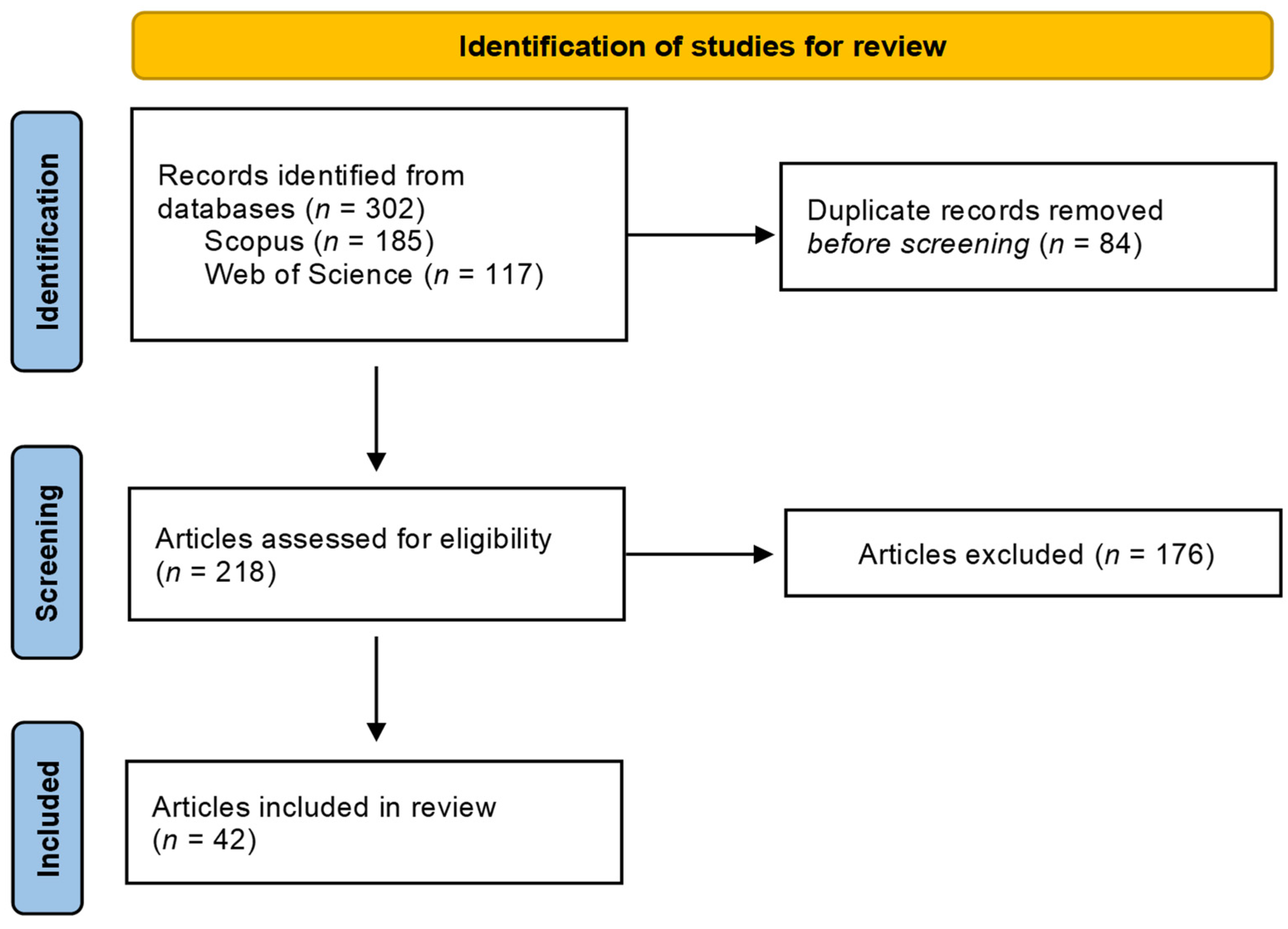

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Access

4.2. Health

4.3. Travel Experience/Satisfaction and Agency

4.4. Māori Wellbeing and Transport

4.5. Pacific Views on Transport and Wellbeing

4.6. Policy and Provider Implications

4.7. Strengths, Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Article | Country | Theme | Method | Mode | Key Points on Transport and Wellbeing of Public Housing Tenants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gwyther (2011) [42] | Australia | Access | Qual | Car, PT | A study of the use of transport and communication technologies by Sydney social housing tenants to form and maintain communities. Constraints (e.g., cost, disability, time) on access to a car or public transport hinder tenants in connecting to others and building social networks. Face-to-face communication is vital to tenants. |

| Fossey et al. (2020) [37] | Australia | Access, travel experience | Qual | PT | A study of housing and neighbourhood experiences of people with mental health issues in Melbourne social housing. Accessibility of local amenities and public transport were particularly important for meeting needs of tenants and for connecting with people. Good access to public transport enhanced participants’ connection to place and sense of being at home. |

| Freund et al. (2022) [44] | Australia | Access | Quant | Non-specific | A study of New South Wales public housing tenants’ unmet needs that contribute to wellbeing. Unmet transport need for access to aged care facilities, assistance services, and appointments ranked around the middle of stated unmet needs of tenants; 13–22% of tenants stated they could use help with transportation. |

| Tomasiello et al. (2020) [67] | Brazil | Access | Quant | Non-specific | A scenario modelling exercise examined job accessibility inequalities under different transport, land use and social housing policies in São Paulo. Transport interventions alone were not enough to address job accessibility inequalities. Emphasises importance of integrating transport and land use policies and carefully considering location of social housing developments. |

| Sheppard et al. (2023) [61] | Canada | Access, older adults | Quant | Non-specific | An assessment of community support service provision at social housing complexes for older adults in Toronto. Although services were consistently provided at social housing buildings, service utilisation was low. Given significant levels of need within this population, it is likely there were barriers to access other than proximity. The authors recommended a coordinated approach by service providers to assess specific local needs for support services and adjust provision accordingly, plus ensuring tenants are made aware of services available and how to access them. |

| Martínez et al. (2018) [64] | Chile | Access | Quant | PT | A comparison of accessibility and public transport service provision to areas of social housing, versus other areas in Santiago. A lack of integration between social housing and transport policy has created inequalities in access/travel times and public transport provision, likely reinforcing the segregation of social housing tenants. |

| Tiznado-Aitken et al. (2022) [66] | Chile | Access | Quant | Non-specific | An analysis of combined housing and transport affordability across Santiago found that people in the lowest income deciles, living in social or subsidised housing, have very limited choice of location and are restricted to peripheral urban areas. This increased transport costs, social segregation and inequalities. |

| Vergara and Riquelme (2024) [57] | Chile | Access, travel experience, women | Mixed | PT, car | An assessment of objective accessibility (using an accessibility index) and experience of access (using interviews and ‘mobile ethnographies’) by people in social (low income) and financially supported (middle income) housing in Temuco, to understand impacts of neoliberal housing policies on urban access. While both social and financially supported housing have similar proximity to services, social housing and women face mobility barriers that restrict access. An unreliable public transport system restricts low-income people’s access to services and contributes to loss of social connections. Having to manage work, childcare and household management reduced women’s perceptions of accessibility, who also faced safety issues around mobility. |

| Cho Yam Lau (2010) [54] | Hong Kong | Access, agency | Mixed | PT | A mixed-methods study using surveys and interviews of unemployed and low-income residents in a public housing “new town” development in Hong Kong. Residents complained of isolation, inaccessible employment, lack of affordable transport choices, high commute costs and long travel times due to the housing development’s location away from employment (despite the provision of rapid-transport (road and rail) infrastructure connecting the development to employment centres). |

| Wang and Cao (2017) [72] | Hong Kong | Access | Quant | PT, walking | An assessment of built environment variables associated with daily activities and travel choices for private and public housing residents. Built environment variables that influence activity and travel choices of private residents had little influence on choices of public housing residents. This contrasted with public housing policy requiring the co-location of public housing with shops, schools and public transport stops, meaning that transport need could be met generally by short walking trips. |

| Lu, Chen et al. (2018) [71] | Hong Kong | Access, health, physical activity | Quant | PT, walking | A study of built environment variables associated with physical activity in older adults living in dense social housing. Older adults living in social housing with more close (<1 km) bus stops, or those with a close subway station, walked more for transport. Those living in areas with more recreational facilities (e.g., parks, sports facilities) undertook more moderate/vigorous recreational physical activity. Those living in areas with greater land-use mix walked less and undertook less recreational physical activity, although the authors note that Hong Kong residents rely heavily on walking and public transport, suggesting a threshold effect of land-use mix on physical activity. |

| Lu, Gou et al. (2018) [59] | Hong Kong | Access, health, physical activity | Quant | PT, walking | A study comparing walking rates in new transit-oriented development (TOD) and pre-TOD urban neighbourhood public housing. Contrary to findings in more car-dominated urban areas (e.g., USA and Australia), people living in newly designed TOD neighbourhoods walked less than those living in older established urban neighbourhoods in Hong Kong. This emphasises the importance of considering local context and the needs and travel patterns of specific public housing tenants during housing design. |

| Chang et al. (2019) [62] | Hong Kong | Access | Qual | PT | A GIS study of inequities in accessibility of urban parks for private and public housing residents. Found inequities in access to parks for public housing residents due to disparities in accessibility and connectivity of public transport, rather than the distribution of parks. Demonstrates the importance of considering transport provision in public housing development. |

| Mesthrige and Cheung (2020) [55] | Hong Kong | Access, travel experience, agency, older adults | Quant | PT, walking | A study of factors influencing residential satisfaction and ageing in place for older residents of public housing. Convenient access to transportation, including walkways, matter for ageing in place. Engagement with tenants is important to understand needs around accessibility and infrastructure (e.g., handrails) to ensure tenants feel satisfied with accessibility and available transport options. |

| Jiang et al. (2021) [73] | Hong Kong | Access, health | Quant | PT | A study of built environment correlates with suicide in public housing tenants. Distance to nearest urban centre and subway stations was associated with increased rates of suicide after controlling for education, income, employment and other socioeconomic/demographic variables. |

| Ho et al. (2022) [38] | Hong Kong | Access, health, older adults | Quant | Walking, PT | A study of environmental correlates with osteoporosis among older adults in public housing. Increased walking was associated with reduced osteoporosis. People living in areas with more public space and within walking distance of health facilities had lower rates of osteoporosis, after adjusting for sociodemographic variables. However, those living very close to public transport facilities had higher rates of osteoporosis; this could be because those with osteoporosis choose to live in these areas. |

| Ho et al. (2023) [39] | Hong Kong | Access, health, older adults | Quant | Walking | A study of environmental correlates with dementia among older adults in public housing. Areas with greater walkability and accessibility were associated with lower risk of dementia among older adults. |

| Okitasari et al. (2022) [60] | India | Access | Quant | Non-specific | The location of public housing and proximity to the city centre were the most important factors influencing the satisfaction of social housing tenants after relocating from slums in Mumbai. This was mainly due to tenants’ ability to access work. |

| Ibem (2013) [63] | Nigeria | Access | Quant | Non-specific | A study of accessibility of public housing to basic services and facilities in an urban area of Ogun State. A lack of policy to ensure housing providers consider access to basic services and facilities (e.g., water and electricity supply, waste disposal, healthcare facilities, schools, etc.) when building public housing has led to too much focus on dwelling supply and not enough on residential quality. This resulted in negative impacts on tenant wellbeing and poor performance of housing schemes. |

| Russell et al. (2024) [80] | New Zealand | Access, travel experience, Māori | Qual | Non-specific | Kaupapa Māori research, in Ōtautahi/Christchurch, using semi-structured interviews to understand Māori social housing tenants’ experiences of transport and the role of transport in their wellbeing. Alongside access to essential services, connecting with whānau, friends and culturally important places were vital for Māori social housing tenants. This access and connection are facilitated by a range of modes, usually determined by barriers to particular transport options, including cost, time constraints, accessibility of other modes, and access to technology (smartphones). Participants were interested in moving to more sustainable travel, although participants noted that a shared electric car scheme being trialled came with multiple barriers for tenants, including having a smartphone, linking to a bank account and having a driver’s licence. |

| Radzimski (2023) [65] | Poland | Access, agency | Quant | PT, cycling | A comparison of accessibility by sustainable transport (public transport and cycling) for social housing versus market-rate housing in Poznan. Low-income social housing was situated in areas of lower sustainable accessibility than market-rate housing, constraining opportunities for low-income social housing tenants and restricting options to reduce transport-related emissions. |

| Abrantes et al. (2015) [34] | Portugal | Access | Qual | Non-specific | Case study of public housing estate renewal in Porto. Restructuring of road networks, removal of physical barriers and other urban design changes improved accessibility for residents and encouraged use of outdoor spaces. |

| Cheruiyot (2024) [68] | South Africa | Access | Quant | Non-specific | Cross-sectional survey of residents in a new public housing development in Guateng that assessed changes in quality of life and household income and expenditure before and after moving in. While quality of life improved, household transport spending also increased with greater distances for commutes and social activities. Financial wellbeing declined. |

| Bostock (2001) [41] | UK | Access, travel experience, agency, women, children | Qual | Car, walking, PT | Interviews with low-income mothers in the Midlands (most of whom are in social housing) found that not only does carlessness restrict access to health, social care, food and other health-promoting destinations, but reliance on walking also has negative effects on family welfare. Walking had contradictory health and wellbeing benefits depending on the walking environment (e.g., deprived environments can feel dangerous and depressing) and whether there is a choice of modes. Concludes that with car-dependent cities, it is important to regenerate the environment around social housing and improve public transport options to reduce social exclusion of tenants. |

| Jones and Mays (2016) [46] | UK | Access, health, travel experience, older adults | Qual | PT, walking | Interviews with people vulnerable to cold weather, including older people in social housing in the Midlands and the North of England. Found a predominant reliance on public transport with complicated journeys including walking (multiple trip legs and trip chaining) due to scarce nearby facilities. Dependence on public transport and walking was an important source of exposure to cold weather. |

| Clary et al. (2020) [56] | UK | Access, health, physical activity | Qual | PT, walking | A longitudinal study of effects of changes in the built environment on physical activity in London found that residents of areas with improved walkability (particularly residential density and land use mix) increased their physical activity. Improving access to public transport was mainly beneficial to higher income people and resulted in decreased physical activity for social housing tenants, possibly due to different work patterns between social housing and market-rent tenants. |

| Ram et al. (2020) [76] | UK | Access, health | Quant | PT, walking | A longitudinal study examining the effects of changes in the built environment on mental health and subjective wellbeing in London. No overall effect on these outcomes was seen in people who moved into a neighbourhood with better access to public transport, better access to parks and better walkability. However, neighbourhood perceptions did improve. This suggests that built environment improvements alone may not be enough to significantly improve wellbeing. However, the authors noted that built environment characteristics were not fully covered and conclusions were at risk of bias (due to poor follow-up). |

| Dennis Lord and Rent (1987) [58] | USA | Access | Quant | PT, walking | Charlotte, North Carolina. A study of satisfaction among public housing tenants at eight public housing sites across Charlotte. The housing sites with the lowest satisfaction scores had the worst public transport frequency and no shops within walking distance. |

| Malmgren et al. (1996) [47] | USA | Access, older adults | Quant | Non-specific | Seattle, Washington. An assessment of access to healthcare by older adults (over 62) in social housing in Seattle. Almost half the respondents had unmet need for access to healthcare, with the main reasons being cost of healthcare and problems with transport, demonstrating the importance of locating public housing in areas with nearby healthcare facilities and affordable transport options. |

| Rosenbaum and Harris (2001) [52] | USA | Access | Quant | PT | Chicago, Illinois. A study of the early changes in wellbeing of tenants moving from public housing high deprivation neighbourhoods to subsidised rental or public housing in lower deprivation neighbourhoods (part of the Moving To Opportunities programme). Those who moved to wealthier neighbourhoods (usually suburban) reported safety gains and better access to local authority-provided facilities, such as parks and playgrounds, but worse access to public transport, shops or healthcare facilities (compared to control group who moved to any neighbourhood). |

| Heinrich et al. (2007) [70] | USA | Health | Quant | Walking | Kansas City, Missouri. A study of built environment correlates with physical activity for public housing tenants. Tenants in areas with greater street connectivity walked more and those in areas with better access to sports and recreation facilities had higher levels of physical activity. |

| Rosenblatt and Deluca (2012) [43] | USA | Access | Mixed | Car, PT | Baltimore, Maryland. A study of why many Moving To Opportunity (MTO) participants moved back to high poverty neighbourhoods in subsequent moves. One influencing factor was that most MTO families did not have access to a car and found the public transport they relied on was inaccessible in wealthier neighbourhoods. MTO families that did move to low-poverty neighbourhoods usually chose neighbourhoods with good bus access. |

| Chan et al. (2014) [36] | USA | Access | Qual | Non-specific | Boston, Massachusetts. A GIS and survey study of access to community facilities and community integration among social housing tenants. Greater local access reduced longer-distance travel and increased community integration. This was particularly notable for community features identified as important by respondents, demonstrating the importance of understanding the needs of people involved. |

| Blumenberg et al. (2015) [35] | USA | Access | Quant | Car, PT | Compared employment and earnings of recipients of subsidised housing vouchers across USA by their access to cars versus access to public transport. Access to cars was associated with better and more stable employment and higher earnings than public transport access. However, public transport was likely important for lower-income households living in denser urban areas. Low-income families use cars less than other groups; their evident need for greater access to economic opportunities may be best served by increased access to cars despite the “conflict with …sustainability”. |

| Scammell et al. (2015) [53] | USA | Access, health, travel experience | Qual | Car, PT, walking | Boston, Massachusetts. A study of barriers and opportunities for healthy eating and physical activity among public housing residents. One common barrier to eating healthy food was the long travel time to access food shops, compounded by having to travel with young children. Access to affordable supermarkets often required using multiple modes of transport (walking, PT, taxis) due to the location of public housing and a lack of car access. Participants who owned a car did not nominate transportation as a barrier to healthy food (although did cite fuel costs). Relying on buses involved many barriers, including scheduling, unreliability and difficulty carrying shopping on buses. Walking was the primary form of physical activity, mostly out of necessity. A lack of nearby parks was a barrier to exercise, particularly for children. |

| Nguyen et al. (2016) [49] | USA | Access | Quant | Non-specific | Charlotte, North Carolina. A study on neighbourhood choice, employment access and location affordability, part of the wider HOPE VI comparison of outcomes for people receiving subsidised private rental vouchers with those in public housing. People receiving vouchers moved to less-deprived neighbourhoods (a requirement of the voucher programme) but had worse employment access and worse affordability than those living in public housing (more centrally located). |

| Haley et al. (2017) [45] | USA | Access | Quant | Non-specific | Atlanta, Georgia. A study of access to transport and unmet need for medical care among social housing tenants. More frequent barriers to access transport are associated with greater unmet need for medical care. Moving to neighbourhoods with better transport access significantly reduced unmet need for medical care. |

| Petroka et al. (2017) [50] | USA | Access, health, older adults | Qual | Non-specific | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Difficulties accessing healthy food due to lack of transport and distance to shops selling healthy food, as well as easy access to unhealthy food were common reasons given for not changing unhealthy diets by older adults in subsidised rental housing. |

| Martinez et al. (2019) [48] | USA | Access, health | Quant | Car | Baltimore, Maryland. A study of food insecurity, diet and exercise among public housing tenants. Access to a car was associated with reduced food insecurity. No associations between car access and diet or exercise were found. |

| Pomeroy et al. (2021) [51] | USA | Access | Quant | Non-specific | Virginia. A study exploring ‘public housing’ tenant perspectives (in both public housing and subsidised market-rentals) on access to healthcare. A lack of transportation was the third most significant barrier to accessing healthcare (22.5% of voucher recipients and 25.7% of public housing tenants stated this was a problem). Transport was also the third-most-cited missing neighbourhood resource by both groups. |

| Wong et al. (2022) [40] | USA | Access | Quant | PT | Los Angeles, California. An assessment of healthcare utilisation by social housing tenants (specifically formerly homeless veterans). Those who lived in neighbourhoods with high public transport use had higher healthcare utilisation rates. |

| Miller et al. (2024) [69] | USA | Access, health, children | Quant | Non-specific | Los Angeles, California. Before–after study of the effects of opening a supermarket on diet of children living in social housing. Proximity to the supermarket correlated with a relative improvement in diet for children with no access to a vehicle compared to children with vehicle access. Overall, proximity to the new supermarket was not significantly associated with changes in diet. |

References

- Randal, E.; Shaw, C.; Woodward, A.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Macmillan, A.; Hosking, J.; Chapman, R.; Waa, A.M.; Keall, M. Fairness in Transport Policy: A New Approach to Applying Distributive Justice Theories. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K. Transport and social exclusion: Where are we now? Transp. Policy 2012, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wee, B. Accessible accessibility research challenges. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 51, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, G.; Martens, K. Accessibility and the Capabilities Approach: A review of the literature and proposal for conceptual advancements. Transp. Rev. 2021, 41, 833–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khreis, H.; Warsow, K.M.; Verlinghieri, E.; Guzman, A.; Pellecuer, L.; Ferreira, A.; Jones, I.; Heinen, E.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Mueller, N.; et al. The health impacts of traffic-related exposures in urban areas: Understanding real effects, underlying driving forces and co-producing future directions. J. Transp. Health 2016, 3, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schalkwyk, M.C.I.; Mindell, J.S. Current issues in the impacts of transport on health. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 125, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, D. Inequality in Transport; Alexandrine Press: Marcham, UK, 2018; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, H. Land use planning and health and well-being. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, S115–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randal, E.; Shaw, C.; McLeod, M.; Keall, M.; Woodward, A.; Mizdrak, A. The Impact of Transport on Population Health and Health Equity for Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand: A Prospective Burden of Disease Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Urban transport justice. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKim, L. The economic geography of active commuting: Regional insights from Wellington, New Zealand. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2014, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heretaunga Tamatea Deed of Settlement. Heretaunga Tamatea and Trustees of the Heretaunga Tamatea Settlement Trust and the Crown Deed of Settlement of Historical Claims 2015. Available online: https://www.tearawhiti.govt.nz/te-kahui-whakatau-treaty-settlements/find-a-treaty-settlement/heretaunga-tamatea/ (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- O’Malley, V. Beyond the Imperial Frontier: The Contest for Colonial New Zealand; Bridget Williams Books: Wellinton, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binney, J.; O’Malley, V.; Ward, A. The Ao Hou The New World 1820-1920; Bridget Williams Books: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018; Available online: https://www.bwb.co.nz/books/te-ao-hou?srsltid=AfmBOorC4kaMh0SlPkzBmfAjHSA1hy-pSzUf3X_4M7w336F8U-_gS2Xb (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Marr, C. Public Works Takings of Maori Land, 1840–1981; Waitangi Tribunal Division: Wellington, New Zealand, 1997.

- Great Britain Privy Council Judicial Committee; New Zealand Legal Information Institute. McGuire V Hastings District Council [2001] NZPC 10; [2001] UKPC 43; [2002] 2 NZLR 577 [2001] NZRMA 557; (2002) 8 ELRNZ 14 (1 November 2001); Judicial Committee of the Privy Council: London, UK, 2001.

- Logan, A. Housing and Health for Whānau Māori. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. The Housing Dashboard June 2024. Available online: https://www.hud.govt.nz/stats-and-insights/the-government-housing-dashboard/housing-register (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Statistics New Zealand. 2023 Census Severe Housing Deprivation (Homelessness) Estimates. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/2023-census-severe-housing-deprivation-homelessness-estimates/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- OECD. Social Housing: A Key Part of Past and Future Housing Policy; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kandt, J.; Rode, P.; Hoffmann, C.; Graff, A.; Smith, D. Gauging interventions for sustainable travel: A comparative study of travel attitudes in Berlin and London. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 80, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, A.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Riggs, L.; Smith, C. Public Housing in an Urban Setting: An inclusive wellbeing framework. Policy Q. 2023, 19, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, G.; Logan, A.; Olin, C.V.; O’Sullivan, K.C.; Robson, B.; Pehi, T.; Davies, C.; Wall, T.; Howden-Chapman, P. A Whakawhanaungatanga Māori wellbeing model for housing and urban environments. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2024, 19, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teariki, M.A.; Leau, E. Understanding Pacific worldviews: Principles and connections for research. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2024, 19, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazener, A.; Sanchez, K.; Ramani, T.; Zietsman, J.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Mindell, J.S.; Fox, M.; Khreis, H. Fourteen pathways between urban transportation and health: A conceptual model and literature review. J. Transp. Health 2021, 21, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruger, J.P. Health Capability: Conceptualization and Operationalization. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinghieri, E.; Schwanen, T. Transport and mobility justice: Evolving discussions. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 87, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raerino, K.; Macmillan, A.K.; Jones, R.G. Indigenous Maori perspectives on urban transport patterns linked to health and wellbeing. Health Place 2013, 23, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Kidd, B.; Wild, K.; Woodward, A. Cycling amongst Māori: Patterns, influences and opportunities. N. Z. Geogr. 2020, 76, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerewa, N.; Stephenson, J.; Hopkins, D. Shared mobility in a Māori community. Kōtuitui N. Z. J. Soc. Sci. Online 2018, 13, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, E.; Olin, C.; Randal, E.; Witten, K.; Howden-Chapman, P. Placemaking and public housing: The state of knowledge and research priorities. Hous. Stud. 2023, 39, 2580–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrantes, N.; Alves, F.B.; Abrantes, V. The city of Porto and the public housing: Learning With design practice. Int. J. Hous. Sci. Its Appl. 2015, 39, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenberg, E.; Pierce, G.; Smart, M. Transportation Access, Residential Location, and Economic Opportunity: Evidence From Two Housing Voucher Experiments. Cityscape 2015, 17, 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D.V.; Gopal, S.; Helfrich, C.A. Accessibility patterns and community integration among previously homeless adults: A Geographic Information Systems (GIS) approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 120, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossey, E.; Harvey, C.; McDermott, F. Housing and Support Narratives of People Experiencing Mental Health Issues: Making My Place, My Home. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.C.; Cheng, W.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lu, S.; Lum, T.Y.S.; Chiu, R.; Webster, C. Spatial uncertainty and environment-health association: An empirical study of osteoporosis among “old residents” in public housing estates across a hilly environment. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 306, 115155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.C.; Song, Y.; Cheng, W.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lu, S.; Lum, T.; Chiu, R.L.H.; Webster, C. How do forms and characteristics of Asian public housing neighbourhoods affect dementia risk among senior population? A cross-sectional study in Hong Kong. Public Health 2023, 219, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.S.; Gabrielian, S.; Lynch, K.E.; Coronado, G.; Viernes, B.; Gelberg, L.; Taylor, S.L. Healthcare Service Utilization for Formerly Homeless Veterans in Permanent Supportive Housing: Do Neighborhoods Matter? Psychol. Serv. 2022, 19, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostock, L. Pathways of disadvantage? Walking as a mode of transport among low-income mothers. Health Soc. Care Community 2001, 9, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwyther, G. New mobilities and the formation and maintenance of the personal communities of social housing residents. Urban Policy Res. 2011, 29, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, P.; Deluca, S. “We Don’t Live Outside, We Live in Here”: Neighborhood and Residential Mobility Decisions Among Low-Income Families†. City Community 2012, 11, 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, M.; Sanson-Fisher, R.; Adamson, D.; Norton, G.; Hobden, B.; Clapham, M. The wellbeing needs of social housing tenants in Australia: An exploratory study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, D.F.; Linton, S.; Luo, R.; Hunter-Jones, J.; Adimora, A.A.; Wingood, G.M.; Bonney, L.; Ross, Z.; Cooper, H.L.F. Public housing relocations and relationships of changes in neighborhood disadvantage and transportation access to unmet need for medical care. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2017, 28, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; Mays, N. The experience of potentially vulnerable people during cold weather: Implications for policy and practice. Public Health 2016, 137, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmgren, J.A.; Martin, M.L.; Nicola, R.M. Health care access of poverty-level older adults in subsidized public housing. Public Health Rep. 1996, 111, 260–263. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J.C.; Clark, J.M.; Gudzune, K.A. Association of personal vehicle access with lifestyle habits and food insecurity among public housing residents. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 13, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.; Webb, M.; Rohe, W.; Noria, E. Beyond Neighborhood Quality: The Role of Residential Instability, Employment Access, and Location Affordability in Shaping Work Outcomes for HOPE VI Participants. Hous. Policy Debate 2016, 26, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroka, K.; Campbell-Bussiere, R.; Dychtwald, D.K.; Milliron, B.J. Barriers and facilitators to healthy eating and disease self-management among older adults residing in subsidized housing. Nutr. Health 2017, 23, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, M.L.; Johnson, E.; Weinstein, A.A. Subsidized Housing and Health: An Exploratory Study Examining Resident Perspectives on Community Health and Access to Care. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2021, 32, 1415–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, E.; Harris, L.E. Low-income families in their new neighborhoods: The short-term effects of moving from Chicago’s public housing. J. Fam. Issues 2001, 22, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scammell, M.K.; Torres, S.; Wayman, J.; Greenwood, N.; Thomas, G.; Kozlowski, L.; Bowen, D. Balancing act: Approaches to healthy eating and physical activity among Boston public housing residents. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2015, 43, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho Yam Lau, J. The influence of suburbanization on the access to employment of workers in the new towns: A case study of Tin Shui Wai, Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesthrige, J.W.; Cheung, S.L. Critical evaluation of ‘ageing in place’ in redeveloped public rental housing estates in Hong Kong. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 2006–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, C.; Lewis, D.; Limb, E.; Nightingale, C.M.; Ram, B.; Page, A.S.; Cooper, A.R.; Ellaway, A.; Giles-Corti, B.; Whincup, P.H.; et al. Longitudinal impact of changes in the residential built environment on physical activity: Findings from the ENABLE London cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, L.; Riquelme, A. Neo-liberalized Housing Policy and Urban Accessibility: The relevance of perception in intermediate cities. The case of Temuco, Chile. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024, 39, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis Lord, J.; Rent, G.S. Residential satisfaction in scattered-site public housing projects. Soc. Sci. J. 1987, 24, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Gou, Z.H.; Xiao, Y.; Sarkar, C.; Zacharias, J. Do Transit-Oriented Developments (TODs) and Established Urban Neighborhoods Have Similar Walking Levels in Hong Kong? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okitasari, M.; Mishra, R.; Suzuki, M. Socio-Economic Drivers of Community Acceptance of Sustainable Social Housing: Evidence from Mumbai. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, C.L.; Yau, M.; Semple, C.; Lee, C.; Charles, J.; Austen, A.; Hitzig, S.L. Access to Community Support Services among Older Adults in Social Housing in Ontario. Can. J. Aging 2023, 42, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Li, X. Public transportation and the spatial inequality of urban park accessibility: New evidence from Hong Kong. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 76, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibem, E.O. Accessibility of Services and Facilities for Residents in Public Housing in Urban Areas of Ogun State, Nigeria. Urban Forum 2013, 24, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.F.; Hodgson, F.; Mullen, C.; Timms, P. Creating inequality in accessibility: The relationships between public transport and social housing policy in deprived areas of Santiago de Chile. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 67, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzimski, A. Accessibility of social housing by sustainable transport modes: A study in Poznań, Poland. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 111, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiznado-Aitken, I.; Lucas, K.; Munoz, J.C.; Hurtubia, R. Freedom of choice? Social and spatial disparities on combined housing and transport affordability. Transp. Policy 2022, 122, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasiello, D.B.; Giannotti, M.; Feitosa, F.F. ACCESS: An agent-based model to explore job accessibility inequalities. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 81, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheruiyot, K. Residential relocation and financial wellbeing: Findings from Golden Gardens housing development in Gauteng, South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2024, 41, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Shier, V.; Wong, E.; Datar, A. A natural experiment: The opening of a supermarket in a public housing community and impacts on children’s dietary patterns. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 39, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, K.M.; Lee, R.E.; Suminski, R.R.; Regan, G.R.; Reese-Smith, J.Y.; Howard, H.H.; Haddock, C.K.; Poston, W.S.C.; Ahluwalia, J.S. Associations between the built environment and physical activity in public housing residents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2007, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.; Gou, Z. The association of built environment and physical activity in older adults: Using a citywide public housing scheme to reduce residential self-selection bias. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cao, X. Impacts of the built environment on activity-travel behavior: Are there differences between public and private housing residents in Hong Kong? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Shen, K.; Sullivan, W.C.; Yang, Y.Y.; Liu, X.M.; Lu, Y. A natural experiment reveals impacts of built environment on suicide rate: Developing an environmental theory of suicide. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.; Price, R.; Signal, L.; Stanley, J.; Gerring, Z.; Cumming, J. What Do Passengers Do During Travel Time? Structured Observations on Buses and Trains. J. Public Transp. 2011, 14, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Brömmelstroet, M.; Anna, N.; Meredith, G.; Skou, N.M.; Chan, C. Travelling together alone and alone together: Mobility and potential exposure to diversity. Appl. Mobilities 2017, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, B.; Limb, E.S.; Shankar, A.; Nightingale, C.M.; Rudnicka, A.R.; Cummins, S.; Clary, C.; Lewis, D.; Cooper, A.R.; Page, A.S.; et al. Evaluating the effect of change in the built environment on mental health and subjective well-being: A natural experiment. J Epidemiol Community Health 2020, 74, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosking, J.; Ameratunga, S.; Exeter, D.; Stewart, J.; Bell, A. Ethnic, socioeconomic and geographical inequalities in road traffic injury rates in the Auckland region. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2013, 37, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iungman, T.; Khomenko, S.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Barboza, E.P.; Ambròs, A.; Padilla, C.; Mueller, N. The impact of urban and transport planning on health: Assessment of the attributable mortality burden in Madrid and Barcelona and its distribution by socioeconomic status. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Khreis, H.; Cirach, M.; Milà, C.; Espinosa, A.; Foraster, M.; McEachan, R.R.C.; Kelly, B.; Wright, J.; et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in urban and transport planning related exposures and mortality: A health impact assessment study for Bradford, UK. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, E.; McKerchar, C.; Berghan, J.; Curl, A.; Fitt, H. Considering the importance of transport to the wellbeing of Māori social housing residents. J. Transp. Health 2024, 36, 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolitho, S.; Huntington, A. Experiences of Maori families accessing health care for their unwell children: A pilot study. Nurs. Prax. N. Z. Inc. 2006, 22, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.; North, N. Barriers to Maori sole mothers’ primary health care access. J. Prim. Health Care 2013, 5, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J.; Pearson, A.L.; Lawrenson, R.; Atatoa-Carr, P. Spatial equity and realised access to healthcare—A geospatial analysis of general practitioner enrolments in Waikato, New Zealand. Rural Remote Health 2019, 19, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.; Tiatia-Seath, J. Travel inequities experienced by Pacific peoples in Aotearoa/New Zealand. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 99, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, K.; Woodward, A.; Herbert, S.; Tiatia-Seath, J.; Collings, S.; Shaw, C.; Ameratunga, S. The Relationship Between Transport and Mental Health in Aotearoa New Zealand: Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency Research Report 675; Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021.

- Ryan, D.; Southwick, M.; Teevale, T.; Kenealy, T. Primary Care for Pacific People: A Pacific and Health Systems View; Pacific Perspectives: Wellington, New Zealand, 15 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, P.; Robb, J.H. Residents’ Assessment of a New Zealand Public-Housing Scheme. Environ. Behav. 1977, 9, 573–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Te Reo Māori Term | Meaning/Expanded Translation |

|---|---|

| Hapū | Extended family and also pregnant/to be pregnant. |

| Hauora | Wellbeing. |

| Iwi | Tribe, extended kinship group, nation, people. |

| Kāinga | Village or settlement. |

| Kaitiakitanga | Stewardship, guardianship, often used in the context of the environment. |

| Kaupapa Māori | A way of thinking and acting that incorporates Māori knowledge, values, and principles, can be applied to research, education and other practices. |

| Manaakitanga | Generosity, hospitality and support. |

| Marae | Traditional social and cultural meeting place. |

| Mauri noho | A state in which the mauri, or life force, is diminished and lacking vigour. From mauri, life force, and noho, to sit still. |

| Mauri ora | A state in which the mauri, or life force is vigorous. From mauri, life force, and ora, life and vitality. |

| Oranga | Health, livelihood, welfare, wellbeing. |

| Rangatiratanga | Self-determination, autonomy, leadership. |

| Te Ao Māori | Literally, the Māori world. Used to indicate a Māori worldview. |

| Te Ao Ōhanga | The world of the economy. |

| Te Ao Tangata | The world of people. |

| Te Taiao | The natural environment (can also include the built environment). |

| Te Tiriti o Waitangi | The Māori language version of the treaty signed by the British Crown and some (over 500) Iwi leaders in 1840. Often referred to as the founding document of New Zealand. |

| Tikanga | Cultural rules, practices and social norms; doing things in the right way. From tika, correct, right. |

| Ūkaipō | The ‘real’ home—one’s true home. Also refers to sustenance—the sustainer—U-kai-po literally means to breast feed in the night, inferring maternal connection, devotion and closeness. It is an active term (the real home is not passive, it sustains). |

| Wairuatanga | Spirituality; the act of being spiritual, recognising the spiritual interconnectedness of all people and things, consistent with and affirming of Māori existential beliefs. |

| Whakawhanaungatanga | The action of creating and sustaining relationships, creating whānau. |

| Whānau | Family and birth as well as the verb to give birth/to be born. |

| Whenua | Land and also placenta—a thing that a person is connected to/an interface/a protector and nourisher in an active sense. |

| Area | Number of Articles | Wellbeing Themes | Transport Modes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Health | Agency and Travel Experience | Car | PT 1 | Walking | Cycling | Non- Specific | ||

| Australasia | 4 (Australia, 3; NZ, 1) | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hong Kong | 9 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| North America | 16 (Canada, 1; USA, 15) | 15 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 8 |

| South America | 4 (Brazil, 1; Chile, 3) | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| UK & Europe | 6 (Poland, 1; Portugal, 1; UK, 4) | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 3 (India; Nigeria; South Africa) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Total articles | 42 | 41 | 13 | 9 | 7 | 23 | 13 | 1 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Randal, E.; Logan, A.; Penny, G.; Teariki, M.A.; Chapman, R.; Keall, M.; Howden-Chapman, P. Transport and Wellbeing of Public Housing Tenants—A Scoping Review. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060206

Randal E, Logan A, Penny G, Teariki MA, Chapman R, Keall M, Howden-Chapman P. Transport and Wellbeing of Public Housing Tenants—A Scoping Review. Urban Science. 2025; 9(6):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060206

Chicago/Turabian StyleRandal, Edward, Amber Logan, Guy Penny, Mary Anne Teariki, Ralph Chapman, Michael Keall, and Philippa Howden-Chapman. 2025. "Transport and Wellbeing of Public Housing Tenants—A Scoping Review" Urban Science 9, no. 6: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060206

APA StyleRandal, E., Logan, A., Penny, G., Teariki, M. A., Chapman, R., Keall, M., & Howden-Chapman, P. (2025). Transport and Wellbeing of Public Housing Tenants—A Scoping Review. Urban Science, 9(6), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060206