1. Introduction

As the world grapples with climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and land degradation, the need for effective urban planning that balances ecological, social, and economic factors has become increasingly urgent [

1]. Rapid urbanization in the Global South exacerbates these challenges by contributing to habitat fragmentation, resource depletion, and environmental degradation [

2,

3]. At the global level, the urgency to build sustainable, resilient cities is reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), while regionally, African cities are increasingly adopting green infrastructure to align with climate adaptation and urban development agendas.

Urban renewal has emerged as a key strategy for addressing the complex social–environmental challenges associated with rapid urbanization and revitalizing deteriorated urban areas, particularly in cities of the Global South [

4,

5]. As urban areas expand, governments are increasingly considering green infrastructure, such as parks, corridors, riverbanks, and open public spaces, to enhance sustainability, livability, and social cohesion [

6]. These projects are often presented as win–win solutions that enhance ecological conditions, create recreational opportunities, and improve urban aesthetics [

7,

8]. However, urban renewal efforts frequently prioritize beautification and economic development over holistic strategies that address biodiversity, equity, and cultural heritage [

9,

10].

The “nature-positive” agenda has emerged in response to the global biodiversity crisis, calling for halting and reversing biodiversity loss by 2030 and achieving full recovery by 2050 [

11]. Nature-positive approaches ensure that human development, including urbanization, leads to net gains for nature rather than further degradation. This concept is gaining increasing recognition through international agreements and initiatives, such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) [

12] and the Nature Positive Initiative [

11]. In urban contexts, embedding nature-positive principles means designing and implementing infrastructure that not only serves social and economic goals but also restores ecosystems, enhances biodiversity, and fosters human–nature connections. Integrating nature-positive thinking into urban renewal is increasingly seen as critical for building sustainable, resilient, and equitable cities [

11,

12].

Addis Ababa, one of the fastest-growing cities in Africa, exemplifies these trends [

13,

14]. Since 2019, the city has implemented a series of urban renewal projects as part of a broader national vision for resilient city development with a smart city strategy to renovate urban infrastructure and tourism hubs. Key initiatives include the Beautifying Sheger Project—a green infrastructure program aimed at revitalizing the Addis Ababa riverside corridor through landscape restoration, walkway construction, and the development of recreational facilities [

15]. Complementary efforts include the development of Unity Park, which repurposes a section of the National Palace grounds into a public park that merges natural and cultural heritage [

16]; Entoto Park, a 1300-hectare green and recreational complex on the city’s northern hills [

17]; and Friendship Park, which integrates fountains, gardens, and walking paths along the riverfront [

18]. Another initiative is the road corridor development, which upgrades major transport routes with improved pedestrian access, greenery, and integrated urban design to enhance connectivity, reduce congestion, and align with the city’s broader vision of sustainable urban transformation [

19]. Together, these developments reflect recent efforts to address urban infrastructure deficits and changing land-use priorities in Addis Ababa through integrated public spaces and corridors planning.

While these initiatives have gained political and public attention, their actual contributions to urban sustainability remain under evaluation. Questions persist about who benefits from these green transformations, how inclusive the planning processes have been, and to what extent these projects address ecological and cultural priorities alongside their social and recreational functions [

20]. The literature in other rapidly urbanizing contexts reveals an uneven integration of biodiversity conservation, limited representation of Indigenous and local knowledge, and emerging risks of social displacement and green gentrification—challenges that are mirrored in similar contexts [

21,

22].

While evaluations of green infrastructure projects are increasingly common globally, studies from African cities remain limited [

23]. Studies across sub-Saharan Africa underscore the multifunctional benefits of GI, including biodiversity conservation, climate resilience, and enhancements to human well-being, while also identifying persistent challenges such as governance deficiencies, land tenure insecurity, and inadequate funding [

24,

25]. In Ethiopia, emerging research offers important insights into GI development and implementation. In Addis Ababa, [

26,

27] demonstrated that access to green spaces is uneven, primarily due to rapid urban expansion and weak planning frameworks. Governance-related challenges, including fragmented institutional mandates and limited stakeholder engagement, have also been recognized as significant barriers [

28]. In southern Ethiopia, [

29] found that although green spaces are valued for recreation, their broader ecological functions remain underutilized. Nevertheless, comprehensive, multi-dimensional evaluations integrating ecological, social, and cultural outcomes are rare.

To assess these dynamics, this study applies the Nature Futures Framework (NFF)—a flexible tool that supports the development of scenarios and models of desirable futures for people, nature, and Mother Earth—developed by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) [

30]. The NFF outlines three complementary perspectives on the relationship between people and nature: Nature for Nature (NN), more space for natural areas and biodiversity, enabling ecological processes to operate with little to no human intervention; Nature for Society (NS), focusing on nature’s contributions to social and economic well-being; and Nature as Culture (NC), which highlights cultural, spiritual, and symbolic connections to nature. The Urban Nature Futures Framework is a framework for scenario building in cities, based on three Nature Futures perspectives [

31]. It aims to create positive visions for nature in urban areas by enabling decision-makers, planners, institutions, and urban dwellers to explore multiple transformative pathways for sustainable cities. Although NFF or the customized UNFF has primarily been used in future scenario planning and global visioning processes, this study operationalizes it as an evaluation tool to assess how recent green infrastructure developments perform across ecological, social, and cultural domains.

Most urban sustainability assessments remain focused on universal, technocratic indicators that overlook local priorities and lived experiences [

32,

33]. There is growing recognition that more inclusive, place-based tools are needed to monitor progress and guide adaptive urban planning [

31,

34]. This framework is particularly well suited to contexts where urban renewal is unfolding rapidly in response to the vision of urban transformation and often in tension with social and environmental goals. Addis Ababa presents a relevant case study for examining the dynamics of nature-positive urban renewal in rapidly growing cities of the Global South.

This study aims to assess the ecological, social, and cultural effectiveness of selected urban renewal projects in Addis Ababa, focusing on flagship parks and the first-phase road corridor development, through the lens of the UNFF. It examines how these projects are perceived by diverse stakeholder groups, including residents, park visitors, corridor users, and experts, and explores how perceptions vary across different demographic and spatial contexts. By adopting the UNFF as an evaluation tool, the study contributes to ongoing discussions on urban nature governance and sustainable city development. Ultimately, this research seeks to provide actionable insights for urban planners, policymakers, and civil society actors striving to create greener, more inclusive, and culturally grounded urban environments. The findings offer empirical insights that advance theory on multifunctional urban green spaces and provide practical guidance for planners seeking inclusive, nature-positive city development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

Addis Ababa, the capital and largest city of Ethiopia, is situated in the central highlands at an elevation of approximately 2300 m above sea level [

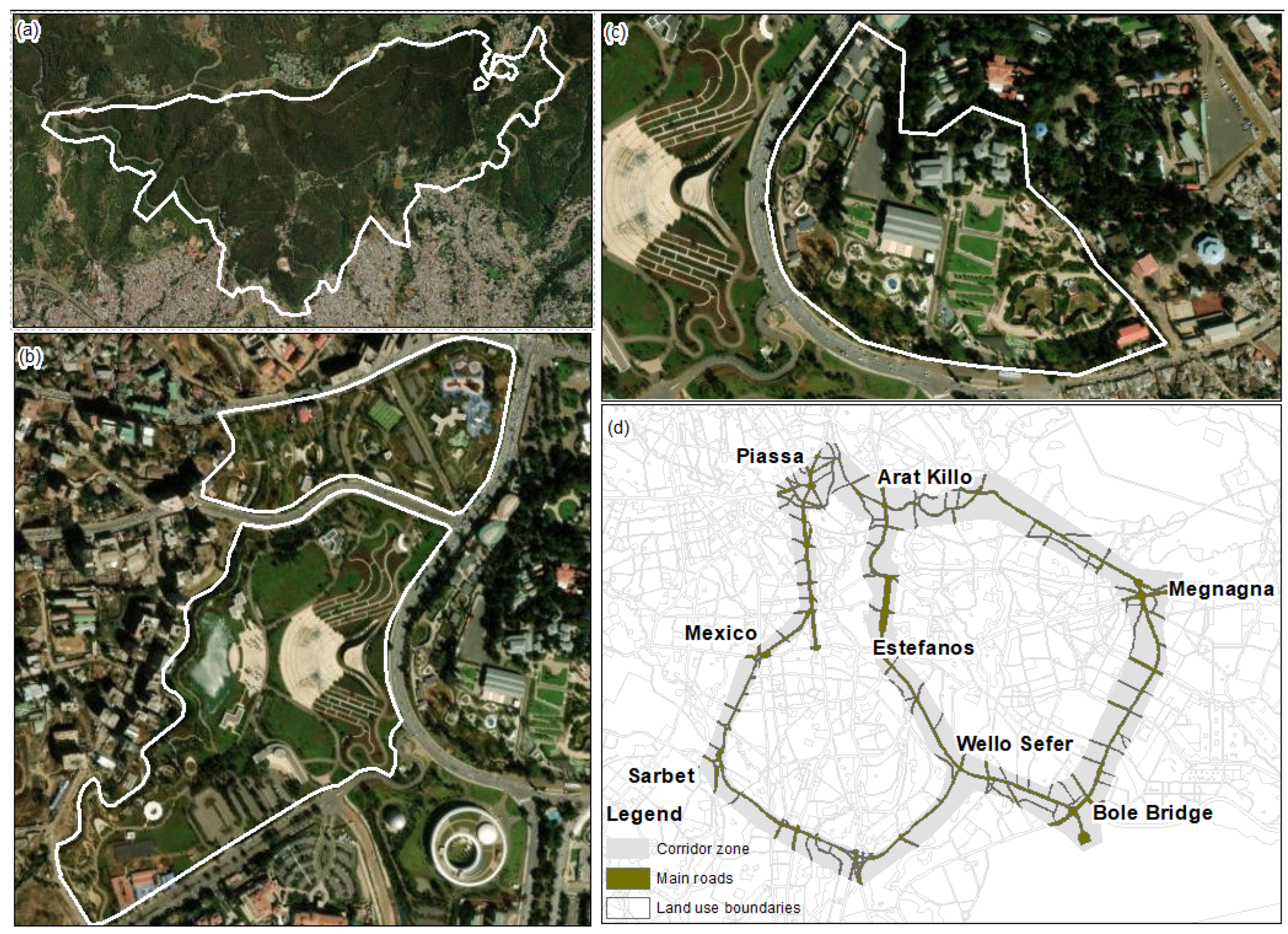

22] (

Figure 1). The city spans over 430 square kilometers and has an estimated population exceeding five million in 2025 [

35]. It serves as the administrative, economic, and diplomatic center of the country. It hosts key continental and international institutions, including the African Union. Over the past two decades, the city has experienced rapid urban expansion, primarily driven by rural–urban migration, population growth, and government-led infrastructure investment [

36]. This growth has led to multiple urban challenges, including limited access to public green spaces, increased traffic congestion, expansion of informal settlements, and environmental degradation [

37].

The current urban development and redevelopment initiatives in Addis Ababa include various green infrastructure projects that address longstanding challenges related to protecting the riverside ecosystem, expanding road corridors, and developing public spaces. These initiatives reflect a range of urban environmental priorities with important ecological, social, and economic implications. A central focus has been the development of three major parks—Unity Park, Entoto Park, and Friendship Parks I and II (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). In parallel, the city has initiated a road corridor development program to enhance mobility, improve pedestrian infrastructure, and integrate green design into key urban corridors.

Unity Park, located within the National Palace grounds and opened to the public in 2019, combines restored historical structures, landscaped gardens, and zoological exhibits [

16]. Covering approximately 20 hectares, it integrates cultural heritage with environmental education, hosting native ornamental trees and species such as crowned cranes and parrots. Entoto Park, situated in the northern highlands of the city, spans approximately 1300 hectares and features a diverse range of recreational trails, natural forest areas, and cultural amenities designed to promote ecotourism and leisure [

17]. It conserves native tree species like

Juniperus procera and

Hagenia abyssinica, alongside the dominant exotic

Eucalyptus globulus, and provides habitat for bird species such as the Tacazze sunbird and thick-billed raven [

38]. The park also encompasses sacred springs and traditional churches of cultural significance. Friendship Parks I and II, located near Meskel Square and major government institutions, offer walking paths, water fountains, botanical gardens, and open-air event facilities [

18]. Together covering about 30 hectares, they contribute to urban leisure, microclimate regulation, and cultural events, with landscaping that supports common urban birds like the Abyssinian thrush and speckled pigeon.

In the first phase, a 40 km corridor is being developed across four main lines: the first extends from Adwa Victory Memorial Square through Arat Kilo, Kebena, and Megenagna; the second connects Arat Kilo to Bole Airport, Bole Bridge, and Megenagna; the third links the New Africa Convention Center to the CMC area; and the fourth runs from Mexico Square through Africa Union, Sarbet, and Wolo Sefer.

This study focuses on four major routes, as shown in

Figure 2d: Arat Kilo–Meskel Square–Bole Bridge (approximately 7 km), Megnagna–Diaspora Square–Arat Kilo–Adwa Victory Memorial (approximately 7 km), Piassa–Legehar–Mexico–Sarbet (approximately 5 km), and Bole Airport–Megenagna (approximately 4.2 km). These corridors are undergoing significant upgrades, including the installation of wider sidewalks, cycling lanes, landscaped medians, street furniture, and stormwater management systems [

19]. While the listed distances refer to the main roads, the project scope also includes improvements to nearby connecting roads. The focus on these four major routes is justified by their strategic role in linking key urban centers, accommodating high pedestrian and vehicular traffic, and serving as showcases for the city’s broader urban renewal efforts. These routes are among the most visible and heavily utilized in the city, where improvements in public space, mobility, and green infrastructure are expected to have the greatest impact on urban quality of life and environmental sustainability.

2.2. Methodology

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to evaluate green infrastructure projects in Addis Ababa through the lens of the UNFF. The methodology followed a stepwise process: establishing the UNFF as the conceptual foundation [

31], developing context-specific indicators, collecting data from four stakeholder groups, and applying both statistical and thematic analyses (

Figure 3). This approach enabled a comprehensive assessment of ecological, social, and cultural dimensions of urban renewal, supporting evidence-based interpretation and policy recommendations.

2.2.1. Development of Indicators

The indicator development process consisted of three phases to ensure both scientific credibility and local relevance. In the first phase, initial indicators were identified based on the three visions of the UNFF [

31]. The NN perspective emphasizes biodiversity conservation, habitat connectivity, and ecological restoration. The NS perspective emphasizes ecosystem services, including air and water purification, heat mitigation, and access to green and recreational spaces. The NC perspective emphasizes the cultural significance of urban nature, encompassing its role in preserving traditional ecological knowledge, fostering a sense of place-based identity, and facilitating cultural expression.

In the second phase, the identified indicators were refined using global sustainability and urban biodiversity assessment frameworks to enhance measurability, comparability, and relevance. The Urban Nature Index contributed metrics related to biodiversity health and species richness [

39], while the Cities Biodiversity Index provided indicators for urban ecological connectivity and the conservation of native species [

40]. In addition, metrics derived from effectiveness frameworks for Nature-Based Solutions were integrated to evaluate the impact of green infrastructure on climate adaptation, stormwater regulation, and pollution control [

40].

The third phase involved validating and refining the indicators through stakeholder engagement and expert consultations conducted in Addis Ababa. This participatory process was crucial for evaluating the feasibility, contextual relevance, and clarity of the proposed indicators within the city’s planning and implementation framework. Stakeholders, including urban planners, environmental professionals, cultural heritage experts, residents, and community representatives, provided critical feedback on the practical applicability and interpretability of the indicators. The insights gathered informed the final revisions, ensuring the indicators aligned with scientific standards and local priorities [

41,

42].

To enhance relevance and ease of understanding, the indicators were tailored to the perspectives of four key stakeholder groups: visitors to major urban parks, users of green spaces along newly developed road corridors, residents living near parks, and experts in relevant fields. Except for the experts, these indicators were then translated into the local Amharic language. Approximately 30 indicators were finalized, with an average of 10 representing each of the three perspectives outlined in the UNFF—NN, NS, and NC. A sample of the expert-focused indicators is provided in

Supplementary Material S1.

2.2.2. Data Collection

The survey questions were formulated using theoretical foundations from the NFF/UNFF and empirical insights from previous urban sustainability studies [

30,

31]. To ensure conceptual alignment, each question was explicitly mapped to one of the UNFF dimensions, focusing on the ecological value, social functionality, or cultural relevance of urban nature.

To collect empirical data for applying the indicators and analyzing stakeholder perceptions, a structured survey instrument was designed and administered across four target groups: residents living near newly established parks, visitors to major urban parks, users of parks and green spaces along newly developed road corridors, and experts in relevant disciplines. The survey consisted of Likert-scale questions rated from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly Agree”), covering key themes such as accessibility, environmental quality, cultural relevance, and perceived benefits of the urban renewal projects. To enhance the reliability and clarity of the questionnaire, a pilot test was conducted with 20 participants drawn from both community and expert groups. The feedback was used to revise unclear items, improve structure, and incorporate reverse-coded questions to minimize response bias.

Data collection was conducted online and in person to ensure broad accessibility across diverse population segments. A structured survey was prepared using Google Forms and distributed digitally via email and social media platforms. In addition, trained surveyors administered the survey face-to-face in key locations to reach respondents with limited internet access and to support participation from underrepresented groups. A stratified random sampling approach was employed to ensure balanced representation, with strata based on demographic variables such as age, gender, education level, employment status, and place of residence. This approach enabled the inclusion of diverse perspectives from across stakeholder groups and geographic areas, both within and beyond Addis Ababa.

A stratified random sampling approach was employed to ensure broad representation across the four main stakeholder groups: residents living near parks, visitors to flagship parks, users of road corridor green spaces, and experts in urban planning, ecology, and cultural heritage. Stratification was based on age, gender, education level, employment status, location, and frequency of green space use. This method ensured the inclusion of diverse perspectives while reducing sampling bias. A total of 525 valid survey responses were collected: 150 from residents living nearest to the parks, 154 from visitors to newly established flagship parks (such as Entoto, Unity, and Friendship Parks), 151 from users of green spaces along newly developed road corridors, and 70 from experts working in urban planning, environmental management, architecture, cultural heritage, and related fields working in the government offices, NGOs, and research and academic institutes. Respondents included individuals residing in Addis Ababa, regional cities, rural areas, and international locations.

Respondents were grouped into four non-overlapping stakeholder categories to capture diverse yet distinct viewpoints based on their primary mode of interaction with the green infrastructure. Corridor users regularly used the upgraded road corridors for commuting, walking, or informal economic activities, but did not reside near or frequently visit the major parks. Park visitors were non-resident individuals who visited flagship parks (Entoto, Unity, Friendship) for recreation or leisure. Residents lived within a 1 km radius of the selected parks, providing insights grounded in daily neighborhood-level interactions. Experts were urban planning, environmental science, or heritage management professionals, offering informed assessments from policy, design, or academic perspectives. Experts were excluded from other groups to maintain group distinctiveness.

In addition to structured Likert-scale questions, the survey included open-ended items designed to capture more detailed and context-rich insights from participants. These questions were tailored to each stakeholder group to explore experiences, perceptions, and suggestions related to urban renewal and green infrastructure projects. For residents, park visitors, and corridor users, the open-ended questions focused on identifying the perceived benefits of the spaces and areas that could be improved. For expert respondents, questions were designed to elicit reflections on the strengths and challenges of project implementation, opportunities for enhancing community involvement, and recommendations for improving outcomes. Including these qualitative items enabled respondents to express perspectives not captured by predefined response options.

2.2.3. Validity and Reliability Testing

To ensure the robustness of the survey instrument, both validity and reliability were assessed. Content and face validity were established through expert consultations and a pilot test with 20 participants from the target groups. Feedback helped refine item clarity, structure, and contextual relevance.

Reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha for each UNFF dimension: Nature for Nature (0.76), Nature for Society (0.81), and Nature as Culture (0.74), all exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.7. These results confirm the internal consistency of the indicators and support their use in further analysis.

2.3. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using quantitative and qualitative techniques, consistent with the study’s mixed-methods design. The quantitative data, derived from Likert-scale survey items, were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistical methods to evaluate perceptions across the three UNFF perspectives. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were used to summarize the level of agreement among the four respondent groups: residents, park visitors, corridor users, and experts. Comparative analyses were conducted across demographic categories (e.g., age, gender, education, employment, visit frequency, and location) to identify patterns and trends in the perceived effectiveness of urban renewal projects.

Furthermore, a regression analysis was applied across all survey types—corridor users, park visitors, residents, and experts—to ensure the comparability of findings. The analysis employed ordinal logistic regression, also known as the Proportional Odds Model, which is well suited for examining ordinal outcomes derived from Likert-type survey responses. The primary objective of the models was to assess the influence of demographic and experience-based predictors on three dependent variables reflecting different perspectives of human–nature relationships: Nature for Nature (ecological or intrinsic value of nature), Nature for Society (social and functional benefits of nature), and Nature as Culture (symbolic, identity-based, or cultural connections with nature). These dependent variables were discretized into three ordinal categories—low, medium, and high—using quantile binning to ensure an even distribution of responses across levels.

For all survey types, the analytical process followed a standardized sequence. Firstly, a common set of demographic and behavioral predictors was selected, including gender, age group, education level, employment status, location, and frequency of park visits. Depending on the context and available data, additional factors such as length of residence, distance to park, or field of study were incorporated. All categorical predictors were transformed using one-hot encoding, with reference categories excluded to avoid multicollinearity. The regression models were fitted using the OrderedModel class from the statsmodels package (version 0.13.5), specifying a logit link function.

To ensure valid and stable model estimates, constant or zero-variance predictors were excluded from the analysis. In cases where model convergence was problematic, simplifications were made to improve stability. Each model output included estimates of coefficients, standard errors, p-values, and 95% confidence intervals. Additionally, model diagnostics such as Log-Likelihood, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and degrees of freedom were reported to evaluate model fit. The core predictors used in all models were gender, age group, education level, employment status, and frequency of visits, all encoded using one-hot encoding after removing constant columns.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Profile of Survey Participants

The study surveyed four key groups—park visitors, corridor users, residents, and experts—to assess the effectiveness of urban renewal initiatives in Addis Ababa (

Table 1). Among residents, 45% were male and 55% were female. Park visitors had a slightly higher proportion of females (53.3%) than males (46.7%). Among corridor users, 53.9% were male and 46.1% were female. Experts had more male respondents (58.6%) than females (41.4%).

Age distribution varied across the groups (

Table 1). Most respondents (37–65%) were within the 18–34 years category, followed by those aged 35–50 (26–64%). The smallest proportion of respondents (8–12%) was in the 51+ years category. Specifically, 52.3% of corridor users, 65.3% of park visitors, and 37% of residents were in the 18–34 age group, while experts had a lower representation in this category (23.8%). The 35–50 years group was well represented among experts (64.3%), residents (42%), and corridor users (26.1%). Park visitors had a slightly lower proportion in this category (32.7%). The proportion of respondents aged 51–64 ranged from 2% (park visitors) to 11.9% (experts), while those aged 65 and above accounted for 12% of residents and 6.3% of corridor users but were absent among park visitors and experts.

Educational attainment also showed notable variation (

Table 1). A significant proportion of respondents had a college diploma or undergraduate degree, ranging from 30% among residents to 49% among park visitors. Experts had the highest level of education, with 83.4% holding graduate degrees or higher. Among residents, 18% had graduate degrees, while 32% of park visitors and 6.3% of corridor users had similar qualifications. Secondary education was the highest level attained by 36% of corridor users, 16.3% of park visitors, and 39% of residents. A small percentage of respondents had primary education, including 17.1% of corridor users, 2% of park visitors, and 9% of residents. Only 5.4% of corridor users and 3% of residents had no formal education, while 1% of residents had attended religious school.

Employment status differed significantly among the groups. Full-time employment was highest among experts (100%), followed by park visitors (52.4%) and residents (27%). Corridor users had a lower proportion of full-time employees (23.4%). Part-time employment was rare, with only 3.6% of corridor users and 2% of residents working in this category. Self-employment was prevalent among residents (44%) and corridor users (32.4%), with 29.9% of park visitors also being self-employed. Unemployment rates varied, with 16.2% of corridor users and 4% of residents reporting being unemployed. Students accounted for 13.5% of corridor users, 10.9% of park visitors, and 9% of residents. A small proportion of respondents identified as housewives (5.4% of corridor users, 4.8% of park visitors, and 6% of residents), while retirees made up 5.4% of corridor users and 8% of residents.

3.2. Evaluation of Urban Renewal Green Infrastructure in Addis Ababa

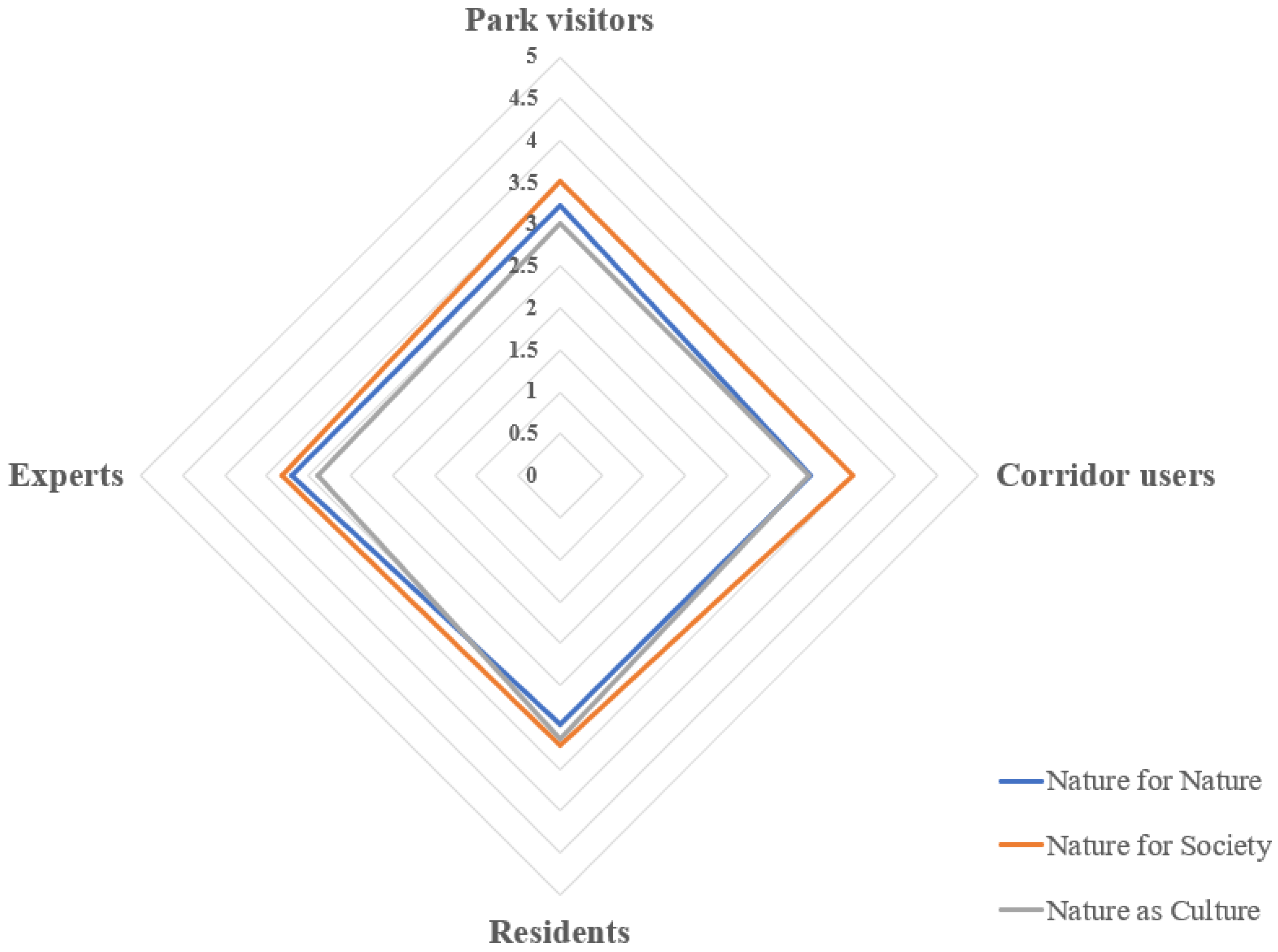

The evaluation of urban renewal projects in Addis Ababa reveals a strong emphasis on social benefits, with NS receiving the highest ratings across all survey groups (

Figure 4). Park visitors (3.52 ± 0.81) and corridor users (3.5 ± 0.61) provided the highest scores, indicating that the focus of green spaces is on recreation and social interaction. Residents (3.21 ± 0.81) also acknowledged the project’s prioritized social benefits, though their ratings were slightly lower. Experts (3.31 ± 0.62) recognized that the orientation of the projects is for social impact, though with some variation in their assessments.

Analysis of individual indicators further reinforces this trend. Among the highest-rated items were “The park is well-maintained and accessible for recreational activities” (3.95 ± 1.22) and “The park supports visitor well-being by offering opportunities for relaxation and stress reduction” (3.94 ± 1.07), indicating that physical usability and psychological benefits are strong focal points of the projects. Similarly, “Facilities such as shaded areas and pathways enhance visitor comfort” received a favorable rating of 3.90 ± 1.22, emphasizing the infrastructure supporting daily use and leisure. However, indicators related to broader ecosystem service functions and participatory components received more moderate scores. For example, “Community-driven initiatives (e.g., tree planting or waste recycling) have been promoted in the project” was rated at 2.33 ± 1.06 by residents and 2.9 ± 0.96 by experts, suggesting limited visibility or engagement of local communities in these efforts. Likewise, the indicator “The renewal project has created more green jobs (e.g., landscaping, maintenance)” received modest ratings (3.07 ± 0.88 by residents; 2.9 ± 0.91 by experts).

The evaluation of NN generally indicated a moderate focus on environmental sustainability. Park visitors (3.22 ± 0.76) and experts (3.19 ± 0.59) provided relatively higher scores, whereas residents (2.96 ± 1.03) and corridor users (2.99 ± 0.66) rated this aspect lower. Specifically, the variety of plants and animals in the park received higher ratings from park visitors (3.49 ± 1.30) and experts (3.36 ± 0.88) compared to corridor users (2.84 ± 1.28) and residents (3.10 ± 1.49). The presence of native plants and trees was moderately acknowledged, with experts (3.02 ± 0.92) giving the highest ratings, while residents (2.90 ± 1.34) rated it lower. Rewilding practices were more positively perceived by experts (3.40 ± 0.96) and park visitors (3.29 ± 0.89), whereas corridor users (3.00 ± 0.00) and residents (3.09 ± 1.36) had more neutral ratings. The maintenance of parks to support animal wildlife was perceived differently, with experts (3.19 ± 0.99) and park visitors (3.12 ± 1.24) rating it higher than residents (2.70 ± 1.41).

Efforts to improve ecological connectivity through green corridors were recognized by experts (3.40 ± 0.96) and park visitors (3.29 ± 0.89). The project’s contribution to improving water quality through pollution control measures was rated highest by experts (3.52 ± 0.97), while corridor users (3.14 ± 1.40) and residents (3.12 ± 1.45) provided moderate scores. Through information boards and guides, biodiversity education received the highest ratings from experts (3.52 ± 0.97), while other groups rated it slightly lower. Measures to control invasive species exhibited a similar trend, with experts (3.52 ± 0.97) receiving the highest recognition, while park visitors and residents provided lower ratings. The experience of nature with minimal urban influence was moderately recognized across groups, with experts (3.52 ± 0.97) and park visitors (3.13 ± 0.92) giving the highest scores. The design of housing and infrastructure to integrate with natural processes received the most recognition from experts (3.52 ± 0.97), while other groups provided moderate ratings.

NC received the lowest ratings. Experts (2.89 ± 0.84) provided the most critical evaluation, followed by corridor users (2.97 ± 0.59) and park visitors (3.02 ± 0.87). Residents (3.14 ± 0.93) provided a slightly higher rating. Indicators related to cultural diversity representation (2.69), artistic elements in public spaces (3.02), and community cohesion through cultural events (2.66) received the lowest scores.

The indicators of cultural diversity and community cohesion through cultural events were among the lowest rated. For example, “Culturally significant elements (e.g., historical landmarks, spiritual sites) are preserved in the park or corridor” received a mean score of 2.61 ± 1.48, while “The design of the park reflects local traditions, architecture, or cultural identity” was rated 2.59 ± 1.36. Likewise, the indicator “The park celebrates cultural identity through art, signage, or installations” received a moderate score of 2.86 ± 1.23, showing a lack of variability but limited evidence of widespread implementation. Among the evaluated items, “Events and activities observed at the park (e.g., cultural festivals, art displays)” received a mean score of 3.3 ± 1.4. This suggests that some visible efforts have been made to integrate cultural programming into park spaces. Overall, the findings suggest that while there is some recognition of cultural programming in park spaces, the design, interpretation, and preservation of cultural identity and heritage are not strongly emphasized in the current urban renewal initiatives.

3.3. Geographic and Demographic Variation

3.3.1. Variations Among Parks and Road Corridors

Urban renewal projects in Addis Ababa exhibit varying levels of effectiveness across different geographic locations (

Table 2). Parks consistently receive higher ratings across all three categories, whereas road corridors show greater variation, particularly in ecological sustainability and cultural integration.

Entoto Park ranks highest among parks in NN (3.55 ± 0.72) and NS (3.80 ± 0.79). Friendship Park and Unity Park also receive strong ratings across these dimensions, with NN scores of 3.48 ± 0.71 and 3.52 ± 0.73, respectively, and NS scores of 3.75 ± 0.77 and 3.78 ± 0.78. The NC ratings for Entoto Park (3.38 ± 0.85), Friendship Park (3.3 ± 0.82), and Unity Park (3.32 ± 0.84) are relatively high.

In contrast, road corridors display more significant variability in urban renewal effectiveness. The Arat Kilo–Bole Bridge corridor performs best in NN (3.33 ± 0.4), reflecting efforts in green infrastructure along this route. However, its NC rating (3.05 ± 0.46) is comparatively lower, indicating limited cultural integration. The Bole Airport–Megnagna corridor receives the highest NC score (3.73 ± 0.41). However, its NN rating (3.32 ± 0.47) remains moderate.

The Megnagna–Piassa and Piassa–Sarbet corridors receive the lowest ratings in NN and NC. The Piassa–Megnagna corridor scores 2.76 ± 0.66 in NN and 2.7 ± 0.59 in NC, while the Piassa–Sarbet corridor scores 2.30 ± 0.6 and 2.74 ± 0.71, respectively.

3.3.2. Variations Among Demographic Groups

The evaluation of urban renewal green infrastructure projects in Addis Ababa reveals varying perceptions across different demographic groups, including residents, park visitors, corridor users, and experts. These differences are influenced by factors such as age, gender, education level, employment status, length of residence, proximity to parks, and frequency of visits (

Supplementary Materials S2).

Residents aged 18–34 years prioritize NN (3.21 ± 0.94), emphasizing the recreational and social benefits, whereas older residents (51+ years) rate NN lower, with those aged 51–64 years (2.76 ± 1.14) assigning the lowest score. Female residents rate NN (3.27 ± 0.86) higher than males (3.15 ± 0.85), while male residents assign slightly higher scores for NN (3.07 ± 1.02). Higher education levels are associated with a greater appreciation for NN, with PhD holders (3.10 ± 0.95) assigning the highest ratings. Government employees (3.22 ± 0.85 for NS) and NGO workers (3.26 ± 0.9 for NS) give higher ratings than private-sector employees. Proximity to parks influences the scores, with those living closest providing higher ratings for NS (3.20 ± 0.86). Frequent visitors (those who visit three or more times per week) assign the highest scores across all dimensions, while infrequent visitors and those who never visit parks report lower ratings.

Park visitors aged 18–34 years assign the highest ratings for NS (3.78 ± 0.74), while older visitors (51–64 years) provide the highest ratings for NN (3.61 ± 0.62). Female visitors (3.76 ± 0.78 for NS) rate social benefits higher than males, who assign slightly higher ratings for NN (3.51 ± 0.69). Graduate degree holders provide the highest ratings across all three dimensions, particularly for NN (3.55 ± 0.75). Full-time employees (3.70 ± 0.76 for NS) rate urban renewal effectiveness higher than students and unemployed visitors. Visitors near parks report higher satisfaction with NN (3.55 ± 0.73) and NS (3.79 ± 0.78) than those from regional cities and rural areas. Frequent visitors (three or more times per week) provide the highest ratings for NS (3.79 ± 0.81) and NN (3.58 ± 0.75), whereas those who never visit assign the lowest scores.

Corridor users aged 18–34 prioritize NS (3.53 ± 0.58). Older visitors (51–64 years) provide the highest NS ratings (3.73 ± 0.55). Female corridor users (3.52 ± 0.57 for NS) rate social benefits higher than males, while males provide slightly higher ratings for NN (3.02 ± 0.67). MSc degree holders (3.14 ± 0.66 for NN, 3.63 ± 0.59 for NS) assign the highest ratings, while PhD holders provide the lowest ratings for NC (2.82 ± 0.69). NGO workers (3.50 ± 0.55 for NS) provide the highest ratings, while private-sector employees assign lower scores for NN (2.87 ± 0.70). Corridor users residing closest to parks report moderate ratings for NS (3.41 ± 0.62), whereas those from regional cities rate NC (2.93 ± 0.62) lower. Frequent corridor users assign the highest ratings across all dimensions, while those who never visit provide the lowest ratings.

Relatively older experts (35–50 and 51–64 years) rate NN (3.29 ± 0.64 and 3.24 ± 0.38, respectively) higher than younger experts (18–34 years), who assign the highest ratings to NS (3.2 ± 0.69). Female experts (3.53 ± 0.51 for NS) rate social aspects higher, while male experts assign slightly higher ratings for NN (3.21 ± 0.61). MSc holders provide the highest ratings for NN (3.28 ± 0.62) and NS (3.41 ± 0.58), while PhD holders assign the lowest ratings for NC (2.51 ± 0.83). Government employees (3.23 ± 0.67 for NN, 3.34 ± 0.62 for NS) and academic professionals (3.19 ± 0.32 for NN, 3.35 ± 0.66 for NS) rate environmental aspects higher, while NGO workers (3.06 ± 0.27 for NC) emphasize cultural preservation. Experts in engineering (3.73 ± 0.28 for NN, 3.49 ± 0.44 for NS) and environmental sciences (3.12 ± 0.77 for NN, 3.28 ± 0.73 for NS) provide the highest ratings. Experts from other sub-cities in Addis Ababa (3.28 ± 0.54 for NN, 3.27 ± 0.66 for NS) provide higher ratings than those nearest to parks. Experts from regional cities in Ethiopia (3.02 ± 0.49 for NN, 3.38 ± 0.65 for NS, 3.05 ± 0.71 for NC) provide higher ratings for NS. Visit frequency affects ratings, with experts who never visit green spaces (3.45 ± 0.26 for NS, 3.45 ± 0.13 for NN) assigning higher scores than those who frequently visit NC (2.96 ± 0.76).

3.4. The Regression Analysis of How Different Socio-Demographic Factors Influenced Respondents’ Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Urban Renewal Projects

Drawing on ordinal logistic regression analyses across four targeted surveys (corridor users, park visitors, residents, and experts), the study examined the impact of demographic and behavioral factors on three dimensions of nature perception: NN, NS, and NC (

Table 3).

Perceptions of NN were generally consistent across groups, with few statistically significant predictors, suggesting that the intrinsic value of nature is broadly recognized, regardless of demographic background. However, some context-specific exceptions were observed. In the experts survey, individuals aged 35–50 showed a borderline significant positive association with ecological valuation. Conversely, in the residents survey, individuals living within 1 km of green infrastructure and those who reported never visiting parks were significantly less likely to express strong ecological appreciation. This trend persisted across other surveys, where NN often showed minimal variation by demographic traits.

More variability was observed in perceptions of NS. Among corridor users, male respondents, those with graduate-level education, and individuals who visited parks frequently (three or more times per week) were significantly more likely to recognize the social and functional benefits of the green infrastructure. For park visitors, while frequent visitation generally correlated with higher scores, visiting more than three times per week slightly decreased perceived benefits. Among residents, those living closer to green spaces or who reported never visiting them consistently showed lower societal valuations. Among experts, individuals aged 35–50 and those working in government displayed significant associations, with government employees showing lower societal valuations, perhaps reflecting a more institutional or policy-oriented perspective that differs from community-level appreciation.

The NC dimension was most strongly influenced by education and visitation behavior, pointing to the importance of reflective engagement in fostering symbolic and identity-based connections with urban nature. Across all survey groups, having a graduate degree consistently predicted stronger cultural associations. Frequent park visits also shaped cultural perceptions, though the effects varied. In the corridor and park visitor surveys, visiting more than three times per week had mixed impacts—either enhancing or weakening cultural connections, depending on the context. Among residents, part-time employment, long-term residence (10+ years), and close proximity to green infrastructure were associated with lower cultural valuations, suggesting that routine exposure without active engagement may lead to desensitization. Among experts, holding a master’s degree emerged as the strongest predictor of high cultural appreciation.

3.5. Strengths, Limitations, and Pathways Forward on Urban Nature Integration in Urban Renewal Projects

Insights from park visitors, road corridor users, residents, and expert informants reveal various perceived strengths and limitations regarding the integration of urban nature into renewal projects in Addis Ababa (

Table 4 and

Supplementary Material S4).

Perceived strengths were reported across all three perspectives. Regarding NS, respondents emphasized the role of urban nature in supporting recreation, well-being, and public health. Features such as pedestrian and cycling paths, seating areas, and opportunities for walking, picnicking, and relaxation were identified as key benefits. Some users mentioned that the availability of clean air and a peaceful atmosphere contribute to their mental and physical health. The projects also enhanced mobility and safety through the construction of well-structured roads and improved lighting. Experts have similarly acknowledged the contributions of green spaces to ecosystem services, including air purification, urban cooling, and climate regulation.

From the NN lens, respondents consistently valued the presence of native trees, ancient vegetation, and natural settings that support biodiversity. These features were associated with improved air quality, the presence of wildlife, and the aesthetic appeal of green and blue infrastructure such as waterfalls and fountains. Park visitors and residents, in particular, emphasized the importance of indigenous species and natural shade, with several suggesting the reduction in eucalyptus plantations, primarily at Entoto Park, and the expansion of more integrated ecosystems. Expert respondents confirmed that these projects support urban biodiversity through habitat restoration and the use of native plants, although they also noted limitations in species selection and ecological planning.

Under the NC perspective, some respondents associated green spaces with cultural and spiritual values. Features such as indigenous trees, cultural houses, preserving religious sites, and cultural symbols (e.g., murals and traditional aesthetics) were mentioned as elements that resonate with local identity. Some respondents called for more substantial incorporation of entertainment and storytelling areas that reflect Ethiopian heritage. Experts recognized the presence of culturally relevant spaces but noted that these elements were not central to project planning or design processes.

Despite these strengths, several limitations were identified (

Table 4 and

Supplementary Material S3). Both community members and experts frequently noted ecological and design-related challenges. Respondents cited the poor condition of some plantings, inadequate watering, the drying of trees, and limited maintenance as areas that need improvement. Requests for more diverse and native vegetation, as well as better integration of wildlife and water features, were common. Experts highlighted environmental constraints, including water scarcity, soil infertility, gaps in ecological suitability assessments, and the limited application of biodiversity principles such as multifunctionality and connectivity.

Planning and implementation challenges were also highlighted. Respondents noted the lack of sufficient recreational amenities, unclear access rights, and gaps in infrastructure, including signage, sanitation, and waste management systems. Accessibility issues were raised, particularly regarding the inclusion of people with disabilities, the elderly, and economically disadvantaged groups. From a cultural standpoint, the limited representation of local traditions, spiritual practices, and historical narratives was reported in the design of parks and corridors. Experts noted that top-down planning often marginalized cultural and spiritual values.

Governance and institutional limitations were also identified. Expert perspectives emphasized weak inter-sectoral coordination, limited technical expertise, and inadequate enforcement of conservation policies. Respondents expressed concerns about unclear access rules and the need for more participatory decision-making processes. Experts also highlighted gaps in stakeholder collaboration and community engagement, noting missed opportunities to incorporate local knowledge and foster long-term stewardship. Financial constraints and lack of sustained maintenance planning were identified as additional barriers.

A key issue identified across stakeholder responses is the displacement of residents and small businesses while implementing urban renewal and green infrastructure projects in Addis Ababa. Several respondents reported experiencing forced evictions without adequate consultation or compensation, particularly in areas affected by road corridor developments. Displacement was seen to disproportionately affect low-income and marginalized groups, who were often excluded from planning and resettlement processes. Beyond physical relocation, concerns were also raised about cultural displacement, including the loss of traditional gathering spaces and spiritual sites.

Community feedback and expert interviews also identified potential pathways forward (

Table 4 and

Supplementary Material S3). Across perspectives, there was a strong emphasis on the need for early and inclusive engagement in the planning and design process. Respondents suggested participatory tools, including mapping, surveys, co-design workshops, and efforts to involve elders, local knowledge holders, and cultural actors. Several noted the importance of integrating local traditions and practices to strengthen place-based identity and ensure relevance.

Education and awareness were frequently mentioned as areas for improvement. Suggestions included environmental literacy campaigns, school programs, and utilizing local media to enhance understanding of the benefits of urban nature. Experts emphasized the value of incorporating nature–culture linkages into outreach efforts through storytelling and culturally sensitive interpretive materials.

Suggestions for institutional reform included developing legal frameworks to support community participation and including cultural rights in urban development policies. Both residents and experts recommended that projects prioritize equitable access, fair compensation for displaced residents, and avoid exclusionary practices. The alignment of green space development with livelihood activities, such as community gardening or ecotourism, was also mentioned. Consistent funding and long-term maintenance plans are critical.

The responses indicate that while there is a broad appreciation for integrating urban nature into Addis Ababa’s renewal projects, the long-term success of such initiatives depends on addressing ecological constraints, strengthening participatory and inclusive governance, and integrating cultural and social values more systematically into urban planning processes.