1. Introduction

While it contributes less to helping cities achieve food self-sufficiency, urban agriculture can set up a pathway to feed the citizens differently [

1]. The ‘in a different way’ approach involves commercialising quality local products via short circuits, a sustainable model that significantly reduces the environmental footprint [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

As a form of nature-based solution, urban agriculture contributes to climate adaptation by enhancing urban resilience, supporting biodiversity, and reducing food-related emissions [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Urban short food chains build on this foundation by reinforcing local food systems that reduce environmental impact and strengthen social cohesion and economic circularity within cities [

13,

14].

Urban short food supply chains (USFC) refer to localised food systems that shorten the distance between food producers and consumers within urban areas or their immediate surroundings. These systems typically involve direct sales models such as farmers’ markets, community-supported agriculture, cooperatives, and urban food hubs, reducing intermediaries and increasing traceability [

13,

15,

16]. Although some definitions emphasise direct producer–consumer interactions, recent research suggests that USFC can take multiple forms, including municipal food procurement, cooperative models, and urban food networks [

13,

17].

USFC aims to promote fresh, minimally processed food, enhance food security, and support local economies, aligning with urban agriculture’s broader sustainability goals.

While USFCs are widely promoted as environmentally friendly alternatives, some scholars argue that their sustainability depends on the efficiency of their logistics [

4,

18,

19,

20]. Unlike large-scale food distribution networks that benefit from optimised transportation routes and economies of scale, USFC may increase per-unit emissions due to fragmented and non-optimized transport, mainly when deliveries involve multiple small-scale producers serving dispersed urban consumers [

19]. This challenge suggests that, while USFC provides advantages regarding food quality, consumer engagement, and support for local economies, their environmental impact requires careful assessment, particularly in urban contexts where transport efficiency varies.

Building on this perspective, USFC emerges as a key mechanism for bridging the gap between food producers and urban consumers. By localising food production and minimising intermediaries, USFC aligns with the broader objectives of urban agriculture, fostering more direct and transparent food networks. However, the effectiveness of these systems depends not only on logistical efficiency but also on consumer engagement and the social acceptance of local food models.

Urban agriculture brings producers and consumers closer and encourages cities to reinvent and rethink their deep-rooted relationship with food. In this relationship, local products are essential to creating producer–consumer relations in a globalised agro-food system [

20]. Their unique selling proposition is based on the localisation of production and the supply chain length in terms of the number of actors involved [

1,

13,

15,

16]. The direct contact and partnership between producers and consumers underscore the distinctive nature of these systems. However, these partnerships can only be established with a shared narrative among stakeholders regarding short food chains in urban areas, which rapidly evolve in the continuous industrialisation of a food system. Understanding the initiating factors is essential for building a collective story and creating sustainable partnerships, emphasising the need for collaboration.

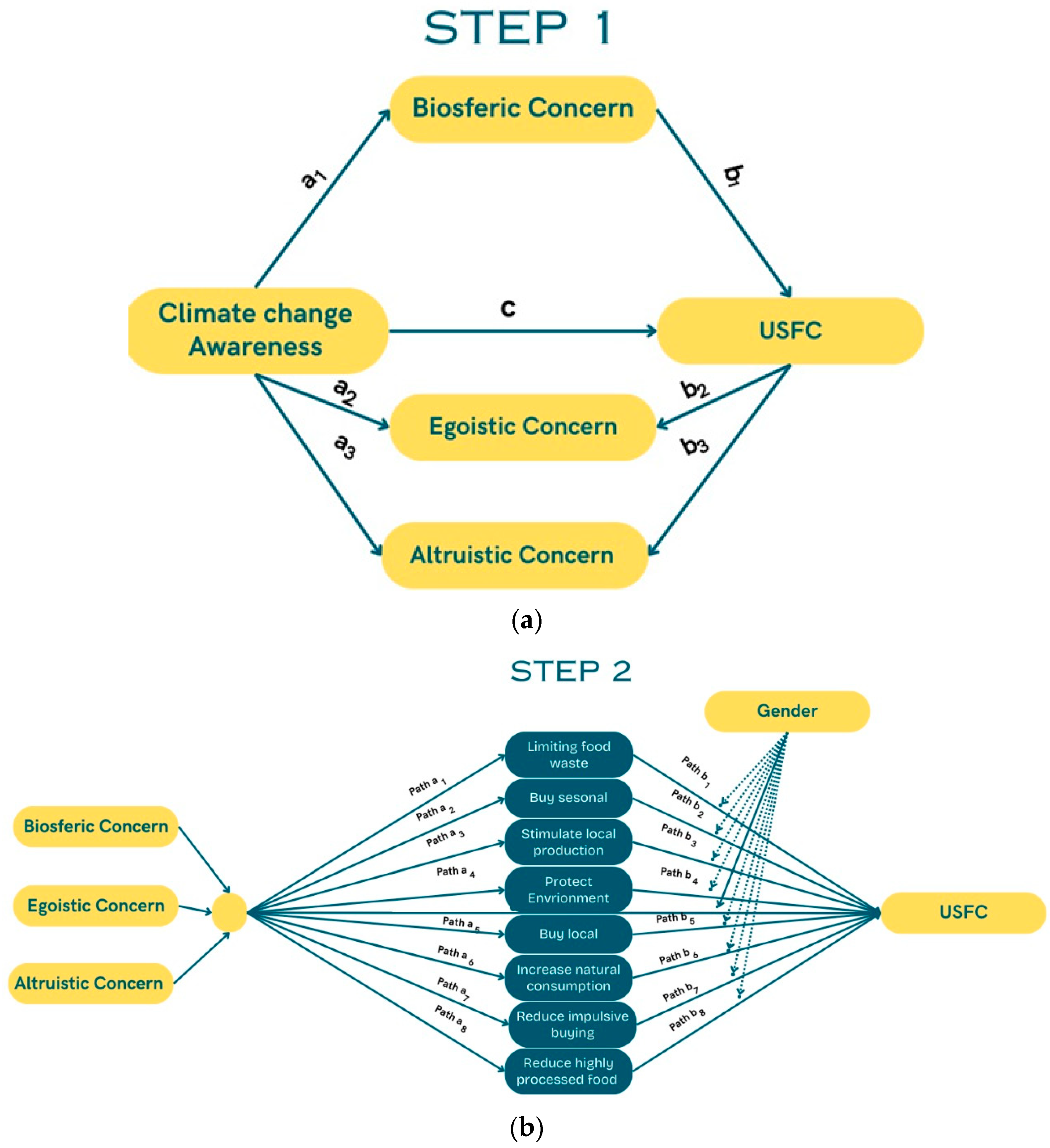

Climate change awareness (CCA) is a powerful driver of sustainable food practices in this context. However, psychological and social factors such as environmental concern often moderate the transformation from awareness into action. Drawing on [

21], this study investigates how different types of concern—biospheric, egoistic, and altruistic—mediate the link between CCA and participation in USFCs.

Despite growing interest in USFCs, there is limited understanding of how climate-related awareness translates into food behaviours in urban contexts, especially through the lens of concern types. Addressing this gap will contribute to designing more effective strategies that align environmental messaging with consumer motivations.

This research contributes to the existing literature by introducing a multi-pathway model that links climate change awareness (CCA) to engagement in urban short food chains (USFCs). It identifies the mediating role of three distinct types of environmental concern—biospheric, egoistic, and altruistic—in shaping sustainable food behaviours. Furthermore, the study explores key consumer drivers influenced by climate-related concerns, such as reducing food waste, preference for seasonal and local products, and avoiding ultra-processed foods. The remainder of this study is structured as follows:

Section 2 outlines the theoretical framework, variables, and methodology.

Section 3 presents the empirical analysis and findings.

Section 4 offers a discussion of the results. Finally, conclusions and implications for policy and practice are presented.

3. Results and Discussion

The study’s findings on CCA among respondents are significant, revealing a high overall awareness level. A mean score of 4 on a 5-point scale indicates that respondents generally consider themselves well-informed about various environmental issues, underscoring the importance of the study’s findings (See

Table 5(1)). The highest mean score of 4.21 is related to awareness of the dangers of air pollution. This suggests that air pollution is particularly salient among the respondents, possibly due to visible effects such as smog or health advisories in Tirana City. Awareness of the environmental damage caused by chemical fertilisers and pesticides is also high, with a mean score of 4.17 (See

Table 5(1)). This could be linked to increasing public discourse around sustainable agriculture and the push for organic products, highlighting conventional farming practices’ environmental and health impacts. The score for awareness of water pollution dangers is 4.12, indicating a significant concern about water quality issues. Awareness of the dangers of insufficient green space and the degradation of cultivated land quality is lower, with mean scores of 4.03 and 3.86, respectively. This suggests that, while these issues are recognised, air and water pollution may take longer for the respondents to respond to. Overall, the high levels of awareness across these areas suggest a well-informed respondent group, particularly regarding issues that have immediate health implications or are frequently highlighted in public discussions on environmental sustainability.

Table 5(2) presents the descriptive statistics for the environmental concern items measured across three dimensions: biospheric, egoistic, and altruistic. The results indicate that respondents most strongly expressed altruistic and egoistic concerns. Items such as

“Children’s Health” (M = 4.78, SD = 0.479),

“My Health” (M = 4.69, SD = 0.557), and

“My Future” (M = 4.67, SD = 0.595) received the highest average ratings, reflecting a strong egoistic orientation, where concern is linked to personal or familial well-being. This is closely followed by altruistic concern with

“All individuals” (M = 4.59, SD = 0.640), suggesting a solid social responsibility toward others.

Conversely, biospheric concerns—related to non-human nature such as

plants (M = 3.98),

aquatic life (M = 4.01), and

birds (M = 3.92)—show slightly lower mean values, though still relatively high. This distribution aligns with previous literature, suggesting that, while people acknowledge the importance of ecological well-being, personal and human-centred concerns often carry more weight in shaping behaviour [

21,

33]. As explored in our hypotheses, these findings are critical to interpreting the mediation effects of concern types in the pathway between CCA and participation in urban short food chains.

Parents’ preference for food product origins indicates a strong inclination towards supporting local products, with 64% opting for those of Albanian origin and 32% preferring EU origin. However, the preference drops significantly to 13% when considering a narrower territory such as Tirana. This disparity might be attributed to concerns over product availability, quality, or perceived reliability from a smaller geographic area. Despite this, 88% of parents are willing to pay extra for food products from their preferred origin: they are typically willing to pay an additional 10–20%. This willingness to pay suggests a substantial market demand for origin-specific products driven by factors such as perceived quality, safety, and support for local economies. The same high level of willingness (88%) to participate in the USFC initiative of Tirana further underscores the community’s commitment to supporting local food systems. About 10% of parents were uncertain, and only 2% were unwilling to participate. Surprisingly, there were no statistical differences in the mean of the WTP for the made-in-Albania label and the made-in-Tirana label. This contradicts the assumption that the WTP for Tirana agricultural products would be higher due to the narrower production area. Other studies have shown that the difference in WTP is even more remarkable when the local claim is expressed as ‘small farm or territory’. The narrower the territory, the higher the WTP [

70,

71]. A well-defined origin increases the ability of the consumer to process the information coming from this information stimulus [

72]. However, the present study has yet to support this result. One possible explanation is the parents’ need for knowledge regarding the capacity of the territory of Tirana to provide agricultural and food products. The collective illusion that cities do not produce food continues; parents, as consumers, play a crucial role in shaping this perception. They do not associate Tirana with a specific agricultural production area. Additionally, the characteristics of the Tirana population play a role. In the last thirty years, Tirana has hosted Albanian individuals immigrating from different regions from north to south; 30% of the Albanian population moved toward Tirana. This trend persists; new parents come to Tirana with their existing territory associations. One study [

73] shows that young Albanians are highly attached to and aware of national issues. However, a commonly shared story linked to Tirana’s territory and agricultural products is needed in this case.

This study examines consumer preferences for local food sourcing in school catering, including urban-scale procurement. However, it does not explicitly differentiate short food supply chains based on the number of intermediaries. Future research should investigate consumer willingness to engage with short food supply chains (0 or 1 intermediaries) versus broader local food systems, ensuring a more precise distinction in food network structures.

The analysis of the demographics concerning motivation shows that gender, age, education and the age of the children significantly influence people’s motivation to pay an additional price to participate in USFCs. This underscores the importance of understanding the demographics of the consumer base. Parents with higher education levels and children aged three to five years old express the highest WTP, 30%. Concerning the relationship with demographics, parents with two children (F value = 3.434;

p value = 0.034), above five years (F value = 5.535;

p value = 0.000), prefer made-in-Albania products over other options. Parents with children under five years of age prefer products of EU origin because they trust EU food safety institutions more than Albanian ones and because of the perception of high-risk food illnesses for that specific age [

74,

75].

The municipality of Tirana and the related stakeholders should play a crucial role in transforming citizens’ perceptions of agriculture in urban areas and creating the city’s food identity. The latter can be built by understanding the parents’ primary motivations for participating in the USFC of Tirana.

In addition, an analysis of parents’ understanding of sustainable consumption and whether it is associated with their willingness to pay shows that about 60% of the participants claim they understand the concept of sustainable consumption, while 40% still need to. Among those who understand, most link sustainable consumption to the energetic aspect, such as the balance of energy intake and expenditure, while 24% associate it with the environmental impact of consumption. Most respondents (around 35%) believe that food consumption is sustainable when the energy value of the food consumed is equal to the body’s energy expenditure. This highlights a significant focus on the nutritional aspect of sustainability, indicating that many parents prioritise the balance between food intake and bodily energy needs. Interestingly, about 25% of respondents associate sustainable consumption with minimising the environmental impact of daily food consumption, showing an awareness of the broader environmental implications of their food choices. Approximately 15% of respondents consider zero food waste to be a critical component of sustainable consumption, which reflects an understanding of waste reduction as playing a part in sustainability efforts. Furthermore, around 12–15% of respondents link sustainable consumption to balancing plant and animal products in their diet and adjusting food costs to the family’s financial capacity. These perspectives highlight a diverse understanding of sustainability, encompassing nutritional balance, economic considerations, and environmental impacts.

This analysis indicates that, while there is a substantial awareness of the energy balance aspect of sustainable consumption, there is also significant recognition of environmental impacts and waste reduction. Similarly, another factor that increases consumer interest in local products and USFC is the evolution of consumer preferences due to globalisation. Consumers, increasingly faced with uncertainty regarding the products they consume and their health effects, are considering alternatives, such as local or fresh products. These schemes are of particular interest to the agricultural systems of developing countries because they address the growing uncertainty of a specific segment of consumers concerning the food they consume [

58,

76].

Table 5(3) shows various motivations for participating in USFC and indicates that the most highly rated are ‘Increasing the consumption of natural foods’ and ‘Purchasing and consuming seasonal foods’, which score above 4.5. This high rating highlights the value and appreciation of fresh and seasonal products and natural foods. Other important motivations include promoting local agricultural/livestock production and protecting the natural environment, which scored around 4.1. This high rating suggests a strong concern for local economies and environmental sustainability. Conversely, ‘Reducing food waste’ and ‘Reducing the consumption of highly processed foods’ have slightly lower scores, indicating that, while these factors are essential, they may only be the primary motivators for some respondents. Exploring behavioural motivations within a rapidly evolving urban food environment—shaped by industrialisation, urbanisation, and the globalisation of food systems—provides valuable insights beyond pre-existing urban food chain structures. However, future research should further differentiate urban food chain mechanisms from broader short food supply chain engagement, ensuring a clearer understanding of consumer drivers and food system dynamics.

These motivations are critical components of the moderation mediation model used in the study, as they help us to understand the pathways through which climate change concerns and environmental awareness influence consumer behaviour and the willingness to engage with USFC. The analysis first investigates the direct and indirect effects of CCA on the willingness to pay (WTP) for USFC, as mediated by biospheric, egoistic, and altruistic concerns (see

Table 6).

As shown in the methodology section, the second step involves analysing the impact of three types of environmental concern—biospheric, egoistic, and altruistic—on the willingness to pay (WTP) for USFC and the mediators linked to USFC.

CCA significantly increases biospheric, egoistic, and altruistic concerns. However, these concerns do not consistently translate into a willingness to pay for USFC. While CCA can increase concerns related to the environment, such as biospheric, egoistic, and altruistic concerns, these concerns do not always lead to actual behavioural changes, such as willingness to pay for USFC. This disconnect, often called the “value–action gap,” is well-documented in environmental psychology [

23,

32,

77,

78]. It occurs because of various factors, such as financial constraints, perceived inconvenience [

79,

80], lack of trust [

76], and competing priorities that can inhibit the translation of environmental concerns into actionable behaviours. Additionally, the perceived personal relevance and urgency of environmental issues may vary among individuals [

79,

81], contributing to inconsistent behavioural outcomes despite similar levels of concern.

Altruistic concern’s significant positive mediation effect on USFC participation suggests that altruistic motivations can enhance engagement in sustainable practices. This finding aligns with the existing literature that emphasises the importance of social and ethical considerations in consumer decision making, particularly sustainability [

36,

82]. Individuals motivated by the well-being of others and the broader community can engage in behaviours supporting environmental sustainability, such as participating in USFC. Additionally, 90% of the respondents are female parents, which is significant, as studies have shown that women are often more engaged in sustainability issues due to their roles in household management and childcare, which heightens their concern for future generations and environmental health [

83,

84]. Conversely, egoistic concern has a significant negative mediation effect, indicating that higher egoistic concern may reduce willingness to pay for USFC (See

Table 7). Egoistic concern focuses on personal benefits rather than collective or environmental well-being. This perspective often leads individuals to prioritise immediate personal gains, such as cost savings or convenience, over long-term environmental benefits [

32,

35]. As a result, individuals with higher levels of egoistic concern may be less willing to pay for sustainable options such as USFC, which often require higher upfront costs or sacrifices for convenience.

The finding that the overall and direct effects of CCA on urban short food chain participation are insignificant highlights the complexity of translating awareness into sustainable consumer behaviour.

The analysis reveals that biospheric concern (EC Biospheric) significantly and positively impacts several drivers of willingness to pay (WTP) for USFC. The most pronounced direct effects of EC Biospheric are seen in the stimulation of local production (effect size: 0.4389, p < 0.000) and protecting the environment (effect size: 0.403, p < 0.000). This underscores the potential for positive changes in the food system, offering an anticipatory pathway. Moreover, increasing natural consumption (effect size: 0.393, p < 0.000) and reducing processed food consumption (effect size: 0.414, p < 0.000) are also strongly influenced by EC Biospheric, further reinforcing the potential for a healthier and more sustainable food system. While the direct effect of biospheric environmental concern (EC Biospheric) on (WTP) is not significant (effect size: 0.717, p = 0.093), this study reveals the significant indirect effects of limiting food waste (effect size: 0.456, p = 0.004) on WTP, underscoring their importance in the context of USFC and making the audience feel informed and aware of these crucial factors.

Increasing natural consumption shows a significant negative mediation effect (effect size: −0.595,

p = 0.033). Cognitive dissonance might play a role here [

85]. Consumers already engaged in increasing natural consumption might feel they are contributing sufficiently to sustainable practices. Therefore, they might perceive less need to further engage in USFC initiatives, viewing them as an additional or redundant effort rather than a complementary one. This leads to a decreased willingness to pay for such initiatives, as people believe their existing actions are adequate. Second, the perceived costs and accessibility issues associated with natural products can contribute to this negative mediation effect. Even though consumers recognise the benefits of natural products, they may associate them with higher costs or limited availability, especially in urban settings. This perception can make them reluctant to pay more for USFCs, which might also be perceived as an expensive or less convenient option. Lastly, saturation and the prioritisation of concerns might be at play. Consumers who are highly focused on natural consumption may prioritise sustainability concerns, such as reducing plastic use or energy consumption, over supporting local food chains [

86]. This prioritisation can result in a lower WTP for USFCs, as these consumers allocate their resources and efforts to other environmental areas they consider more impactful or immediate.

Gender significantly moderates the relationship between EC Biospheric and WTP, with an important negative interaction effect (effect size: −0.865, p = 0.024). Specifically, EC Biospheric negatively impacts WTP for females (effect size: −1.013, p = 0.007) but not for males (effect size: −0.148, p = 0.227). One possibility is that women, who constituted 90% of the sample, might have a more nuanced view of environmental concerns, potentially reflecting greater awareness of the complexity and challenges involved in sustainable practices. Women are often more directly involved in food purchasing and preparation and may thus be more cautious about changes that could affect household routines or budgets, especially in urban areas where time and resources are limited. Prior research suggests that women are more engaged in sustainable food networks and local food purchasing decisions.

The role of women in sustainable food networks, such as USFCs, as well as their influence on local food purchasing decisions, is becoming increasingly important within the discourse on food security and environmental sustainability [

87,

88,

89]. Women’s involvement is critical for ensuring food security at the household level and in advancing community sustainability efforts [

87,

90]. Women’s participation in sustainable food networks is underscored by their unique purchasing behaviours and motivations [

88,

91,

92,

93]. Research shows that women tend to prioritise environmental and social considerations more strongly than men, making them more likely to purchase local and sustainably produced foods [

94]. For example, studies highlight that women are often the primary decision makers regarding food purchases, which has a profound impact on family dietary diversity and overall nutrition [

91,

95]. Furthermore, women are increasingly aware of the social implications of their food choices, fostering more substantial support for local economies through informed purchasing decisions [

96].

Women are also significantly involved in establishing and maintaining alternative food networks, which emphasize local food production and consumption. Their engagement in these networks often reflects a commitment to sustainable practices, community well-being, and ethical considerations in food sourcing [

93,

97,

98]. For instance, initiatives such as food cooperatives, where women play a central role, enable collective action towards sustainable food sourcing while fostering community ties [

98]. Such cooperative structures empower women through shared leadership and decision making and address barriers linked to individual purchasing power and access to sustainable food options [

98]. In urban contexts, women’s networks can enhance food security by enabling access to local and fresh produce while negotiating better purchasing conditions, such as buying on credit from informal vendors [

88].

Women’s active participation in urban sustainable food networks is critical for advancing environmental and social sustainability.

Our findings reveal that egoistic environmental concern (EC Egoistic) significantly influences various drivers of willingness to pay (WTP) for USFC. The largest direct effects of EC Egoistic are observed in reducing processed food consumption (effect size: 0.405, p < 0.00) and increasing natural consumption (effect size: 0.320, p < 0.000). Stimulating local production (effect size: 0.303, p < 0.000) and protecting the environment (effect size: 0.294, p < 0.000) are also significantly impacted.

Although the direct effect of EC Egoistic on WTP is not significant (effect size: 0.338,

p = 0.317), significant indirect effects through limiting food waste indicate an important mediation pathway (effect size: 0.447,

p = 0.006). Increasing natural consumption shows a significant negative mediation effect (effect size: −0.731,

p = 0.011). Gender significantly moderates the relationship between EC Egoistic and WTP, with a notable negative interaction effect. An interaction effect is the combined effect of two or more variables on the dependent variable (WTP). Consumers’ budget constraints may influence the negative mediation effect of increasing natural consumption on WTP for USFC, as natural or organic products are often perceived as more expensive [

99]. Additionally, it is important to understand that urban lifestyle constraints, such as time and convenience, play a significant role in consumer choices [

100]. Scepticism about the benefits of natural foods and these lifestyle constraints may deter consumers from opting for natural consumption despite potential benefits [

101].

The analysis also uncovers the significant influence of altruistic concern (ECA) on various drivers of willingness to pay (WTP) for USFC. The highest direct effect is observed in reducing processed food (effect size: 0.545, p < 0.000) and increasing natural consumption (effect size: 0.472, p < 0.000). These results highlight the potential of altruistic concern. The overall model for WTP reveals a non-significant direct effect of altruistic concerns (effect size: 0.652, p = 0.091). However, the indirect effects achieved through various mediators are of paramount importance. Limiting food waste shows the highest positive indirect effects on WTP (effect size: 0.502, p = 0.002), indicating intense mediation. Increasing natural consumption has a significant negative mediation effect (effect size: −0.663, p = 0.021). Gender plays a significant moderating role, particularly for WTP (interaction effect size: −0.729, p = 0.021).

The findings of this study align with those of previous research on environmental concerns and sustainable food choices. Like [

45,

46], our results confirm that biospheric concerns strongly influence preferences for natural and minimally processed foods, reflecting a broader trend in sustainable consumer behaviour. Additionally, the indirect effect of limiting food waste as a driver of willingness to pay (WTP) for USFC reflects the conclusions of [

44], who highlight food waste reduction as a critical component of sustainability in local food systems.

Moreover, our findings regarding the role of egoistic concerns in processed food reduction are consistent with [

56], who found that personal health concerns significantly drive sustainable food choices. However, unlike studies that emphasise a strong direct effect of CCA on behaviour [

102,

103], our results indicate that CCA alone does not directly translate into WTP for USFC but operates through mediating factors. This suggests that awareness must be paired with targeted interventions to bridge the value–action gap, a finding that expands on other [

104] work on consumer trust in short food supply chains.

The demographic challenge of urban food perceptions in Tirana also connects with the literature on urbanisation and food system restructuring [

2,

15]. Similarly to findings from [

48], our results indicate that urban consumers often lack strong associations between their city and food production, reinforcing the need for a shared narrative to integrate urban agriculture into food policy discussions.

4. Conclusions

This study examined the role of environmental concerns, specifically, biospheric, egoistic, and altruistic concerns, in mediating the relationship between climate change awareness (CCA) and willingness to pay (WTP) for urban short food chains (USFC). The research aimed to understand how these environmental concerns shape consumer behaviour and engagement in sustainable food practices, particularly in urban settings such as Tirana, Albania. Our findings contribute to the growing literature on sustainable food systems and provide a nuanced understanding of the mechanisms that link environmental awareness to sustainable consumer behaviour. H1: CCA significantly increases biospheric concern: this hypothesis was supported, as CCA was shown to increase biospheric concern (Path a1) significantly. However, the indirect effect of biospheric concern on WTP for USFC was not significant (Path b1), indicating that, while individuals care about environmental issues, this concern does not always translate into actual behavioural change, confirming the existence of the value–action gap. Regarding H2: CCA significantly increases egoistic concern, and this hypothesis was also supported. Our findings indicate that CCA significantly increases egoistic concern (Path a2). Still, this concern negatively mediated the relationship between CCA and WTP for USFC (Path b2), which suggests that people with stronger egoistic concerns are less likely to engage in USFC, as they prioritise personal benefits over collective environmental outcomes. Moreover, concerning H3: CCA significantly increases altruistic concern; this hypothesis was supported, with CCA significantly increasing altruistic concern (Path a3). Additionally, altruistic concern positively mediates the relationship between CCA and USFC participation (Path b3), highlighting the importance of social and ethical motivations in promoting sustainable food choices.

The study’s primary goal was to explore how environmental concerns mediate the relationship between climate change awareness and willingness to pay for USFC. Our results align with this goal, showing that environmental concerns are significant mediators, though the effect is more complex than previously assumed. Specifically, while biospheric and altruistic concerns positively influenced USFC participation, egoistic concerns had a negative mediating effect. This reinforces the idea that consumer behaviour is influenced by environmental awareness and personal values and priorities.

Our study also advances the conceptual model by demonstrating that CCA alone cannot translate directly into sustainable behaviours. Instead, increased awareness and targeted interventions, such as reducing impulsive buying and promoting local production, can foster engagement in sustainable food practices. These insights are crucial for informing future research and policy development, particularly in addressing the industrialisation of food systems and the rise of ultra-processed food consumption.

Another important finding is the significant role of gender in moderating the relationship between environmental concerns and WTP for USFC. Our study found that women, who made up 90% of the sample, exhibited a more substantial negative interaction effect with biospheric concerns, suggesting that women may be more cautious about adopting sustainable food choices due to constraints related to household responsibilities and urban lifestyles. This aligns with global trends recognising women’s pivotal role in shaping food systems, particularly in sustainable food networks. Their involvement is critical for advancing food security and sustainability at the household and community levels.

Despite its valuable insights, this study has several limitations concerning sample composition. The sample was predominantly composed of women (90%) and parents (96%), mainly due to the distribution of the questionnaire through school networks and parent groups. While this allowed us to capture the views of a critical demographic segment, those primarily responsible for food purchasing and household nutrition, it limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader urban population. Future research should aim to include a more balanced representation of genders, age groups, occupational backgrounds (including those in environmental fields), and residential areas (urban vs. peri-urban/suburban) better to reflect the diversity of consumers in urban food systems. Expanding the demographic scope will help capture the full spectrum of motivations, barriers, and engagement strategies needed to promote USFC participation across various consumer segments.

This study underscores the need for policy interventions that bridge the gap between awareness and action. While CCA alone does not directly influence WTP for USFCs, policies can leverage behavioural nudges, financial incentives, and local food initiatives to encourage sustainable food choices. Strengthening urban agriculture in Tirana’s food narrative and public procurement policies favouring local produce, educational programs, and incentives for urban farming could significantly enhance consumer engagement in USFCs.

Furthermore, our findings contribute to the broader discourse on the European Green Deal and its alignment with EU policies, particularly the Farm to Fork initiative. Future research should provide concrete policy recommendations tailored to the local context, addressing key barriers such as limited consumer awareness, logistical inefficiencies, and institutional fragmentation that may hinder the development of urban short food chains. Additionally, exploring the role of digital technology, such as online platforms, mobile applications, and traceability tools, can offer innovative pathways to enhance consumer engagement, improve transparency, and scale up participation in USFC initiatives in urban settings.