1. Introduction

The rate of urbanization has long been theorized to be correlated to socio-economic development, which in turn predicts a shift towards democratization, particularly driven by citizens’ support for democracy [

1,

2]. In the context of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), however, this theory appears not to hold true. By the 1960s, as SSA countries continued to gain independence, urban dwellers as a percentage of the total population were estimated to be only 14.9%, which comprised about 32 million urban dwellers in the region [

3]. Today, the urban population in the region is projected to grow to an estimated 47% of the total population by the year 2030, which is over 600 million people [

3]. In fact, according to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UNDESA), SSA is currently experiencing the highest urbanization rates globally [

3].

Furthermore, transition to democratic governance in SSA has been a much-delayed reality as compared to other developing regions of the world [

4,

5]. A report in 2023 by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) found that countries in the region today are democratic in name only, and only a handful can be said to be somewhat democratic [

6]. Hence, in SSA, where many countries are undergoing rapid urbanization and economic development, while also experiencing non-democratic governance, understanding these relationships is crucial for predicting the process of political development in the region.

This research explores a critical yet much under-investigated aspect of this complex conundrum: the moderating effect of urbanization rate on the relationship between citizens’ perception of socio-economic performance of government and support for democracy in SSA. As countries in the region experience unprecedented urban growth, the urban context may significantly shape how citizens evaluate their governments’ socio-economic performance and, consequently, citizens’ preference for democratic principles of governance. This study aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing democratic support in the region. The study not only contributes to the theoretical debate on democratization, but also widens the aperture for policymakers seeking sustainable development and the strengthening of democratic processes in rapidly urbanizing nations of the Global South.

The study utilizes the Round 8 Afrobarometer individual-level survey data collected between 2019 and 2022 on citizens’ perceptions of socio-economic performance indicators of government and attitudes related to democracy for 32 national-level SSA countries. The selected dataset is used in this study as it focuses on an under-investigated subject. We have found that there is a gap in the literature pertaining to urbanization, democracy, and socioeconomic performance specifically in SSA. Urbanization rate data from the United Nations were also attained for each SSA country in the study. Through a rigorous statistical analysis, we investigate how the varying levels of urbanization rates moderate the relationship between citizens’ perception of their governments’ socio-economic performance and support for democracy. The findings of this research have significant implications for our understanding of democratic governance in the context of developing countries of SSA. Through illuminating the complexity of the relationship between the variables investigated, the study contributes a more nuanced understanding of these evolving dynamics in the region.

The literature review examines three interconnected themes central to unpacking the complex relationship dynamics between economic development, urbanization rate, and support for democracy. We first explore the direct influence of economic development on support for democracy among citizens, which has been extensively debated in the political science and development literature. This includes a critical assessment of empirical findings and theories on measuring economic development, and their influences on democratization and citizens’ support for democratic governance.

We then investigate the relationship between urbanization rates and support for democracy. As SSA countries are currently experiencing rapid urbanization, understanding how this phenomenon affects political preference towards democratic governance is crucial, as several countries in the region have recently experienced civil unrest, violence, and military coups d’état. The study will further synthesize research on forms and processes of the urban environment’s role in fostering or hindering democratic sentiments among citizens. This will be followed by addressing the methodological challenges and approaches in measuring support for democracy in the literature. We will examine the differing indicators and frameworks that have been used to assess citizens’ attitudes toward democratic governance, paying special attention to the SSA context.

1.1. Socio-Economic Development and Democratization

During the 1950s and 1960s, scholars in the fields of sociology, economics, and political science produced and developed the theory of modernization, primarily as a direct response to the increasing number of postcolonial nations going through economic development after World War II. Leaning heavily on Emile Durkheim and Max Weber’s views on industrial societies, Parsons [

7] pioneered the concept of modernization theory, positing that development involved a movement from traditional to contemporary values, occurring alongside an alteration of individual and social subsystems. Levy [

8] expanded on Parson’s work by adding to the dichotomy of traditional and modern, framing the Western nations as epitomes of advanced modernity, the Soviet Union as modern with an irrational divergence from the ideal capitalist path of Western liberalism, and the rest of the world meandering along at different stages of underdevelopment.

Lipset [

1] further developed the theory linking economic development and institutional legitimacy of government as the catalyst to democracy. More precisely, scanning across a broad range of socio-economic indicators, Lipset introduced the pioneering concept aligning elevated standards of affluence, industrial development, urban growth, educational attainment, and the endurance of democratic governance [

9]. Lipset’s enhancement of the theory built upon Daniel Lerner’s concept that modernization follows a single-track progression through four separate stages: economic growth driven by rural-to-urban migration, hastened by rising literacy levels, succeeded by sophisticated media networks, and culminating in widespread civic engagement [

10]. These early theorists, and modernization theory itself, had largely been part of a zeitgeist of the Cold War era, and much of their works and others heavily reflected the communism vs. liberal capitalism argument [

11,

12].

The common view that prosperity stimulates democracy, often referred to as the Lipset hypothesis, however, has been questioned on its legitimacy. While this theory has been shown to hold when assessing a majority of European and other Western countries, it has had less of an impact in a region such as SSA [

13,

14]. For example, according to data by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), between 2000 and 2020, several African countries experienced high rates of economic growth, with several listed as the fastest-growing economies globally [

4,

15]. Yet, the state of democracy in SSA has steadily declined, with several countries experiencing civil unrest, violence, and coups d’état during the past decade [

6]. This puts into question whether the method of using real gross domestic product (GDP) is the best way of measuring the economic development of countries, as it may not truly reflect citizens’ socio-economic well-being given governments’ actions and performance.

First, what does economic performance mean, and how do we measure it? In the field of economics, these factors pertain to GDP, employment generation, earnings, joblessness figures, quality-of-life indicators, and the accumulation of economic resources. In the assessment of modern democratic societies, for example, increase in income per head is an acceptable measure of socio-economic well-being [

16]. On the other hand, a growing number of social scientists and researchers have begun to use individual-level perception of socio-economic well-being as a proxy for economic development [

17,

18,

19,

20].

When considering how to operationalize and measure citizens’ perception of the socio-economic performance of a government, however, it becomes a complex reality. Banting et al. [

21] (p. 63) point out that unlike “the official world of GDP, or productivity and unemployment rates, we enter the decidedly murkier realm of public perception… we carefully use the term ‘official’ rather than objective economy to point out that an official statistical description of economic reality is not necessarily the ultimate criterion, or ultimate truth”. The extent to which a link exists between perception of economic performance and the ‘official’ economic performance of a country also faces differing views. Page and Shapiro [

22] contend that public perceptions of economic performance change in predictable ways and are closely associated with tangible, quantifiable economic outcomes. On the other hand, studies have also shown that the link between objective and subjective economic measures is not consistently reflected in the statistical evidence [

23,

24].

It is also important to differentiate the concept of perceived economic performance from perception of social well-being. The literature on social well-being suggests that, for most people, it measures the perception of overall quality of life at the individual and group levels [

20]. Within the social sciences, social well-being is often operationalized as the subjective evaluation of life through satisfaction and affect [

25,

26,

27]. Moreover, there has been a widespread discussion on its relevance and the multifaceted approach to evaluating the productive value of various social phenomena, especially in the context of efforts to measure the factors driving current and future well-being more precisely [

28].

To ameliorate these limitations, studies have used citizens’ perceptions of their government’s performance related to socio-economic indicators as a proxy for economic conditions [

29]. Research concerning the impact of perceived socio-economic performance (PSEP) on support for democracy indicate that there is a statistically significant relationship between the two variables [

30,

31]. For example, research using economic voting theory has found a significant correlation between PSEP and voter behavior towards democratic governance outcomes [

32].

1.2. Support for Democracy

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, it can be argued that democracy is “the only game in town” [

33] (p. 15), and support for democracy appears to be a widespread and a globally favored form of government by all different types of societies, crossing religions, cultures, and even regime types [

34]. For countries in SSA, growing support for democracy has significant implications for political and social stability. Coupled with rapid urbanization, understanding current trends of how support for democracy is associated with perceived socio-economic performance of governments is key to mitigating civil unrest and driving the region towards sustainable development.

Measuring support for democracy has traditionally taken two main approaches. The first approach uses opinion survey data using a straightforward question that asks whether respondents support democracy. Studies using this approach found overwhelming favor for democracy amongst all respondents, raising questions of the validity of the results amongst social scientists [

35,

36,

37]. The main issue is whether respondents understood the word ‘democracy’ to begin with. Kiewiet de Jonge [

38] addressed this problem of ‘regime abstraction’, which may occur when respondents’ response is in relation to their perception of an ideal system of democratic governance, rather than in relation to how democratic governments function.

One main reason for this may be due to participants’ little personal experience living under democratic systems [

39]. Another reason may be the result of participants focusing on ‘democratic’ regimes in the abstract, rather than a particular democratic system [

40]. Yet another reason for this may be due to participants referring to support for democracy in relation to their current government rather than the concept of democracy itself [

38]. Within all these possible cases, it is assumed that abstraction biases exist when using this method of measurement for support for democracy, particularly in nations that have had no or little experience living under democratic governance.

The second type of methodology relies largely on surveys that measure support for democratic institutions, processes, and values through various other questions that could represent support for democracy [

41,

42]. Survey questions through this methodology measures citizens’ perceptions of governance, rather than actual government performance. Questions may examine citizens’ perceptions of support for open elections, opposition parties, and types of governments vis-à-vis measuring respondents’ support for democracy. Inglehart [

36] (p. 51) suggests that survey questions that measure the “qualities of tolerance of outgroups, interpersonal trust, the post-materialist emphasis on civil rights and political participation” do not explicitly reference democracy; however, these attitudes are societal-level indicators that can measure SFD. However, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance suggests that researchers using any given value as measurement for support for democracy should place them in the context of the society being surveyed and studied [

43].

As previously discussed, studies have used perceived socio-economic performance as a predictor of support for democracy, particularly in terms of economic and policy outputs shaping support for democratic governance [

44,

45,

46,

47]. For example, Armingeon and Guthmann [

48] showed the declining support for democracy in European countries after the financial crisis of 2008, which was directly linked to perception of socio-economic performance. Hence, the review of the literature leads to our first research question: does perception of government’s socio-economic performance predict support for democracy in SSA? Moreover, we can hypothesize that as citizens’ perception of government performance according to socio-economic indicators increases, support for democracy also increases.

1.3. Urbanization, Development, and Support for Democracy

The literature on the benefits of urbanization for economic development has its roots in the earliest periods of the Industrial Revolution. Some core attributes include that urbanization enables specialization, as shown by Fleischacker [

49], while Ciccone and Hall [

50] argued that it increases both input and output productivity. Furthermore, Parr [

51] and his research demonstrated that it decreases transportation costs, and Krugman [

52] showed that it fosters agglomeration of industry. The overall estimation of these theoretical concepts links urbanization to increased productivity, which leads to workers garnering higher wages, in turn leading to increased economic capital and a better standard of living [

53]. Hence, increase in urbanization rate is correlated to economic development.

Urbanization in the developed world generally has long been linked to the structural transformation from an agrarian to an industrialized economy, distinguished by a labor push and labor pull drivers of a rural-to-urban transition [

54]. Labor push occurs during a green revolution achieved through rise in agricultural productivity, which releases labor from subsistence farming to a modern sector, most profoundly in industries around urban centers—the labor pull factor. These two labor factors have underscored the urbanization experience of most Western and Asian developed nations and economies [

55]. Greater opportunities in urban centers attract people to cities during structural transformation of economies. Urbanization rates, therefore, rise as countries transform their economies from majority agriculture to industries of scale. However, this has not been the case for SSA countries’ current rapid urbanization trend [

56]. Research has shown that the current urbanization rates in the region are highly driven by population growth and decline in mortality rates and not necessarily due to economic development or structural transformation [

57,

58]. This has meant that rapid urbanization in SSA has outpaced socio-economic development. For example, governments in the region have not kept pace in infrastructure development and job creation, leading to high levels of urban poverty and inequality in urban areas.

The role of cities and urbanization rate influencing support for democracy has seen less of a widespread inquiry in the literature within the SSA context. Using empirical evidence, Wallace [

59] shows that dictatorships in urbanized societies face much higher risk of regime change than less urbanized societies. Djankov et al. [

60] further point out that urbanization in developing countries may also have a dual relationship with the types of regime people desire. The theory suggests that cities enable trade, innovation, and economic well-being, which may be stifled by strong dictatorial-type regimes. In this case, citizens should and usually do incline towards support for democracy. On the other side of the coin, cities pose many negative social ills, such as high rates in crime, congestion, disease, etc. Where this is the case, to reduce the threats of urban ills, an increase in demand for dictatorship may be ripe. Furthermore, SSA has the highest youth population globally, with over 60% of the population under the age of 25. Glaeser and Steinberg [

2] have found that while youth generally show higher levels of support for democracy, if socio-economic conditions are poor, it can lead to disillusionment with democratic governance.

To summarize, the literature review examined the relationships between socio-economic development, urbanization, and support for democracy, with a focus on SSA. Modernization theory posits that economic development drives democratization, but this has not held true in SSA, where rapid economic growth has not led to corresponding democratic progress. Instead, perceived socio-economic performance (PSEP)—how citizens evaluate their government’s economic and social policies—has emerged as a critical factor influencing support for democracy. Studies show that higher PSEP correlates with greater democratic support, though traditional economic indicators like GDP may not fully capture citizens’ well-being or perceptions. Additionally, urbanization, a key driver of economic development in other regions, has taken a unique trajectory in SSA, where rapid urban growth has outpaced infrastructure and job creation, leading to urban poverty and inequality. Urbanization’s impact on democracy is complex: while cities can foster innovation and demand for democratic governance, they can also exacerbate social ills, potentially increasing support for authoritarian solutions.

The theoretical framework of the research centers on the interplay between PSEP, urbanization, and support for democracy. It posits that PSEP directly influences democratic support, with citizens more likely to favor democracy when they perceive their government as effectively managing socio-economic conditions. Furthermore, urbanization rate moderates this relationship, as the urban context shapes how citizens evaluate government performance and their preference for democratic governance. We hypothesize that first, higher PSEP increases support for democracy, and second, urbanization rate moderates the strength of this relationship, with the effect of PSEP varying across different levels of urbanization. This framework aims to provide a nuanced understanding of the factors driving democratic support in SSA, contributing to both theoretical debates and policy discussions on sustainable development in rapidly urbanizing regions.

2. Materials and Methods

Data for the dependent and independent variables come from the Afrobarometer (ABM) survey. ABM is an independent, nonpartisan pan-African research project that conducts public attitude surveys on democracy, governance, economic conditions, and related issues in more than 30 countries in Africa. Although international organizations such as the UN and the World Bank provide a wide variety of socio-economic statistical data, ABM is the world’s leading research project that provides public opinion survey data on a variety of topics that affect ordinary Africans. In addition, ABM formulates its questionnaires to address some localized issues, such as recent elections, political parties, ethnic and/or religious-based internal conflicts, and other micro-level variables.

For almost two decades, ABM has conducted eight rounds of cross-sectional surveys across the continent. The most recent completed survey, “Round 8”, conducted between 2019 and 2022 in 34 countries, will supply the data used for this study. While the merged “Round 8” data encompassed 34 countries, as this study is primarily concerned only with SSA countries, two North African countries (Tunisia and Morocco) have been excluded. The final dataset produced N = 38,401 cases in the sample comprising 32 merged SSA countries.

2.1. Variables and Measurments

2.1.1. Dependent Variable

The principal dependent variable is support for democracy (SFD). It will be measured using IDEA [

6] guidelines on creating indices using multiple indicators as measurement of support for democracy. This study looks at the aggregated data for SSA and will not be a cross-national comparison study. For this reason, a more general approach to measure support for democracy will be used.

To create the dependent variable, we first selected three survey questions that measured respondents’ attitudes related to democratic governance. These questions were presented on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disapprove) to 5 (Strongly Approve).

Statement A: “Only one political party is allowed to stand for election and hold office”.

Statement B: “The army comes in to govern the country”.

Statement C: “Elections and Parliament are abolished so that the president can decide everything”.

However, to align the scale of the dependent variable (DV) to a similar scale as the independent variable (IV), we recoded the DV so that it aligns with the scale of the IV. In this case, the DV was recoded so that its scale ranges from 1 (Strongly Approve) to 5 (Strongly Disapprove). This was necessary so that both variables would have the same directional scale for consistency in the regression analysis.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the three questions, showing that there were no missing data.

We then conducted an exploratory factor analysis to determine whether these three items could be combined into a single construct. The analysis revealed that all three items loaded strongly onto a single factor, suggesting that they collectively measure a common underlying concept, which we interpreted as level of support for democratic governance. The factor loadings for each item were found to be sufficiently high, ranging from 0.743 to 0.790, to justify their inclusion in a composite measure. We also examined the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to assess the internal consistency of these items, which, as

Table 2 shows, confirmed their reliability at the scale of α = 0.59. While this alpha value is below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, alphas of 0.50 to 0.60 are sufficient for a relatively new area of research and where the items in our index variable are theoretically related, even with a lower alpha [

61].

Based on these results, we created an index variable by calculating the mean score across the three items for each respondent. This approach gives equal weight to each of the three questions in the final index. The resulting index variable ranges from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating stronger support for non-democratic governance forms. This index variable serves as our dependent variable in subsequent analyses, providing a more robust and comprehensive measure of attitudes towards democratic governance than any single item alone could provide. By combining these three items into a single index, we can capture a broader range of democratic preferences, including support for a multi-party system, civilian governance, and presidential democracy.

2.1.2. Independent Variable

The independent variable is perception of socio-economic performance (PSEP). It is based on a series of nine selected indicators that were derived from questions 50a–i of the ABM survey. The questions asked respondents how they perceived their government’s performance on socio-economic issues along a Likert-style scale ranging from 1 (Very Badly) to 5 (Very Well).

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics for the nine questions, showing that there were no missing data.

To ensure the validity and reliability of our index variable, we first conducted an exploratory factor analysis to determine whether these nine items could be combined into a single construct. Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was employed. The results revealed that all nine items loaded strongly onto a single factor, with factor loadings ranging from 0.625 to 0.738. This suggested that the items collectively measure a common underlying concept, which we interpreted as perceived government socio-economic performance. We then assessed the internal consistency of the nine items using Cronbach’s alpha.

Table 4 shows that the analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of a = 0.867, which is significantly higher than the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, indicating good internal consistency reliability. Based on the results of the factor analysis and reliability test, we created an index variable.

2.1.3. Moderating Variable

This study seeks to measure the moderating effect of urbanization rate on the relationship between perception of socio-economic performance and support for democracy. Hayes [

62] defines and conceptualizes a moderation model as a condition in which an association between the variables X and Y is said to be moderated in its size or sign by a third variable or set of variables M. A conceptual model for this study is presented in

Figure 1.

The moderating variable, which is the urbanization rate of countries in SSA, is measured as the annual percentage change in population of people moving from rural to urban areas (

Table 5). The Afrobarometer Round 8 data for the 32 countries were collected between the years 2019 and 2022. The urbanization rate for each country, on the other hand, was obtained from the World Bank for a ten-year period between 2010 and 2020. The average urbanization rate of this period is used as the moderator variable measure.

2.2. Methods of Analysis

A moderated relationship occurs when the effect of one variable X on another variable Y depends on or can be predicted by a third variable M [

62]. This study applies a moderation analysis using Andrew F. Hayes’ process regression analysis in SPSS statistics 27.0 software. It estimates a moderated regression model predicting support for democracy Y from perception of socio-economic performance X, while including a three-way interaction between the two variables and urbanization rate M (the moderating variable). The statistical equation for a simple moderation is presented in Equation (1), while the statistical model is presented in

Figure 2.

In Equation (1), i1 is the intercept, representing the baseline level of support for democracy when both perception of government performance and urbanization rate are zero. The term b1X shows the direct effect of government performance perception on support for democracy, telling us how a unit increase in perception of socio-economic performance is associated with changes in support for democracy, holding urbanization rate constant. The term b2M shows the direct effect of urbanization rate on support for democracy, with the coefficient measuring how a unit increase in urbanization rate is associated with changes in support for democracy, holding socio-economic constant. Finally, b3XM shows how the relationship between government performance perception and support for democracy changes with varying level of urbanization rate.

3. Results

The following are the results of the moderation analysis in which the perception of government socio-economic performance (X) is the independent variable, support for democracy (Y) is the dependent variable, and urbanization rate is the moderator. First,

Table 6 presents the overall model, which was found to be statistically significant (

F(3, 45,680) = 173.774,

p < 0.001,

R2 = 0.011), with 1.1% of the variance explained by the variables in the model. While the model suggests that perception of government socio-economic performance, urbanization rate, and their interaction have a statistically significant impact on support for democracy, the overall explanatory power of the model at

R2 = 0.006 is very low. This indicates that other factors not included in the model may play a much larger role in explaining support for democracy.

Second,

Table 7 presents the predictor variables’ influence on the outcome variable. When examining perception of government socio-economic performance (X), it is found to have a significant negative effect on support for democracy (b = −0.094, t(45,680) =−21.076,

p < 0.001), suggesting that higher perceptions of government performance are associated with lower support for democracy. To be specific, for every one-unit increase in perception of socio-economic performance, we see a −0.094 decrease in support for democracy.

Similarly, urbanization rate has a significant negative effect on support for democracy (b= −0.021, t(45,680) = −5.678, p < 0.001). For every one-unit increase in urbanization rate, we see a −0.021 decrease in support for democracy. This implies that higher urbanization rates are linked to decreased support for democracy.

The interaction between X and M is also significant (b = −0.010, t(45,680) = −2.532, p = 0.011). This indicates that the relationship between the perception of government socio-economic performance and support for democracy is moderated by the urbanization rate. Furthermore, the negative impact of socio-economic performance perception on support for democracy intensifies at higher urbanization rates.

To summarize, this analysis demonstrates that both the perception of government socio-economic performance and urbanization rate negatively influence support for democracy, and that these effects are interdependent. The moderating role of urbanization suggests that in more urbanized contexts in SSA, negative perceptions of government performance more strongly detract from citizens’ support for democratic governance.

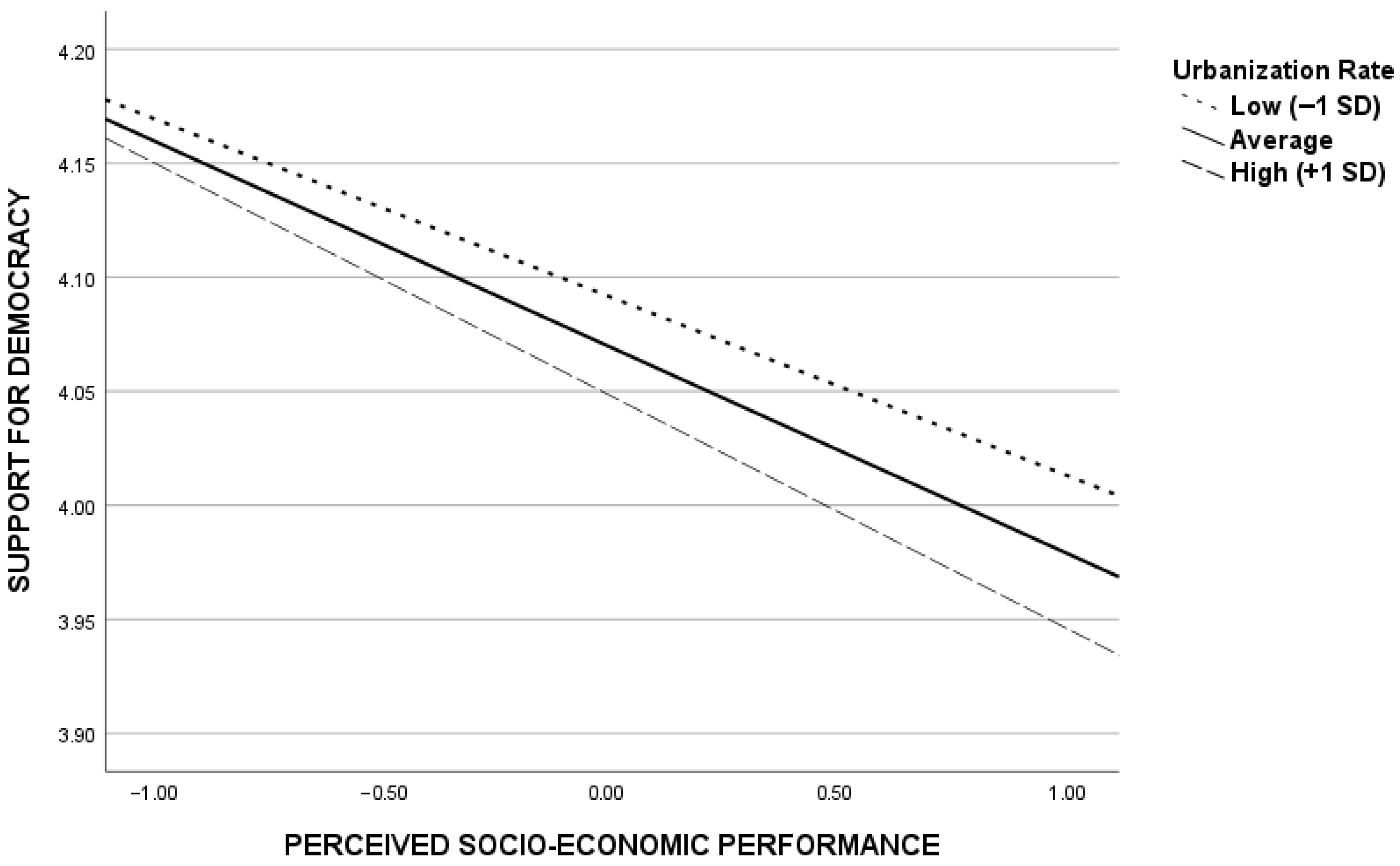

Lastly, simple slopes for the conditional effect of perceived socio-economic performance on support for democracy were tested at different levels of urbanization rate, as shown in

Table 8. The analysis was mean-centered, dividing the moderator (urbanization rate) into three levels: 1) low (−1 SD below mean), 2) moderate (mean), and 3) high (+1 SD above mean).

Each of the slopes revealed a significant negative association between perception of socio-economic performance and support for democracy. The average urbanization rate was 3.64%, and at this level, it was statistically significant (b = −0.094, t(45,680) = −21.076,

p < 0.001), with mean urbanization rate predicting a conditional effect of perception of socio-economic performance on support for democracy by 9.4%. At low (−1 SD) urbanization rates, the result was significant (b = −0.082, t(45,680) = −12.292,

p < 0.001), with urbanization rate predicting a conditional effect of perception of socio-economic performance on support for democracy by 8.2%. The interaction at high (+1 SD) urbanization rates was also statistically significant (b = −0.106, t(45,680) = −17.291,

p < 0.001), with a conditional effect of 10.6% explained by urbanization rate between the relationship of the predictor and outcome variables.

Figure 3 below plots the simple slopes of the moderating effect of urbanization rate on the relationship between perception of socio-economic performance and support for democracy.

It is important to note that low levels of urbanization rate are found to be reversed in support for democracy due to perceived socio-economic performance. At the low rates of urbanization (−1 SD below the mean), the relationship between socio-economic performance and support for democracy is weaker, while at a high urbanization rate (+1 SD above the mean), the relationship between socio-economic well-being and support for democracy becomes stronger. This pattern can be seen in high-urbanization-rate countries such as Ethiopia, Mali, and Burkina Faso, in comparison to lower-urbanization-rate countries like Cabo Verde and South Africa.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide important insights into the complex relationships between citizens’ perceptions of government socio-economic performance, urbanization rates, and support for democracy in SSA. Contrary to the expectations set by modernization theory and previous research in Western contexts, our results reveal a negative inverse relationship between perceived socio-economic performance and support for democracy in SSA countries. While economic development and satisfaction with government performance have historically been associated with increased democratic support, this does not hold true in the context of SSA. The findings instead paint a contrary picture indicating that socio-economic performance is negatively correlated with support for democracy among citizens, meaning that citizens with a lower perception of their socio-economic conditions tend to support democracy, while those with a higher perception lean towards non-democratic regimes.

According to IDEA [

6], democracy has been on a downward trend globally in the last decade despite the economic and technological progressions of the 21st century. Surprisingly, this trend has been witnessed in countries that have historically been considered beacons of democracy, including the United States and European nations such as Austria and Hungary. Furthermore, elements of democracy such as political representation and citizen rights have seen notable declines in all regions of the world. In Africa specifically, coups d’état, insecurity, and civil wars have been identified as significant factors curtailing democracy [

43]. Since the year 2020, there have been six West African nations that have been subjected to successful or attempted coups. These include coups in Mali which took place in August 2020 and May 2021, Chad in April 2021, Guinea in September 2021, Sudan in October 2021, and Burkina Faso in January 2022 and September 2022, as well as an attempted coup in Niger in March 2021 followed by a successful one in July 2023 [

63]. Consequently, about 150 million people in the Sahel region are now living under military regimes [

64].

As coups continue to take place in SSA, public support for military regimes has been on the rise. Rivero [

65] postulates an institutional model to explain this phenomenon. Institutionalism contends that military regimes require legitimacy to garner support from their citizens. This legitimacy is gained from the perception of governmental institutions’ performance in handling socio-economic issues. He found that the tendency to support military rule is seen in citizens who perceive socio-economic matters as being handled appropriately and, hence, perceive political parties as promoting division rather than unity. He further argues that education plays a crucial part in support for non-democratic regimes in SSA, where lower levels of education have been found to result in greater support for military governments.

Similarly, our findings demonstrate that urbanization rates play a significant moderating role in the relationship between perception of socio-economic performance and support for democracy. As urbanization levels increase, the negative impact of perceived socio-economic performance on democratic support intensifies. This finding is particularly relevant given the rapid urbanization currently occurring across SSA. It suggests that the urban context may be amplifying citizens’ dissatisfaction with government performance and translating this into decreased support for democratic governance.

As the literature had suggested, a rapid rise in urbanization leads to a decline in support for democracy. Additionally, support for democracy is lower at higher urbanization rates than at lower urbanization rates. This can be explained by several possible factors. First, although SSA countries are urbanizing at a rapid pace, it has not been a result of industrialization and structural transformation. In fact, with an average urbanization rate of 3.64%, most of the region is still predominantly rural as compared to other developing regions such as Southeast Asia and parts of Latin America. Furthermore, a recent study has shown that SSA’s current urbanization trend has not been driven by a green revolution or an industrial revolution, but rather by natural resource exports [

66]. This illustrates that SSA does not follow the democratization patterns seen in Western nations, which is contrary to Lipset’s hypothesis [

1]. As previously discussed, the downward support for democracy in SSA is evident, with several countries experiencing civil unrest, armed conflict, and coups d’état. For example, nations like Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, etc., which are some of the poorest in the region and have seen higher-than-average urbanization growth, have seen a rise in nondemocratic regimes, specifically military junta regimes [

64].

Second, support for democracy may exist at a higher level in countries that are less urbanized, as populations in rural areas experience higher rates of poverty, perhaps attaching ideals of democracy to socio-economic benefits [

67]. In the recent Western context, the idea that rural areas tend to be more eager seekers of democracy than their urban counterparts also raises the question of the discrepancies between developed and developing regions. Perhaps China is the greatest example. China’s success as an economic power was never reliant on its democratic governance.

Finally, while urbanization is seen to be a positive enabler of socio-economic development and prosperity, its effects are twofold [

60]. On the one hand, urbanization is seen to promote advancements in trade, technology, education, income, etc. On the other hand, urban areas tend to experience more socio-economic challenges, such as increased unemployment and crime and lack of adequate infrastructure such as roads, housing, water, and sanitation facilities. These challenges linked to urbanization would then lead to disillusionment with democratic governance [

2].

5. Conclusions

This study holds significant value, as it delves into an underexplored dimension of urbanization and democratization within the SSA context. By employing a quantitative moderation analysis, the research provides a crucial understanding of how urbanization influences the link between citizens’ perception of socio-economic performance and their support for democracy. As urbanization accelerates in SSA, it brings forth distinct challenges that affect socio-economic conditions and democratic governance. Contrary to established Western democratic trends, this study further uncovers a unique pattern where urbanization negatively moderates the relationship between PSEP and democratic support, contributing to the rise of non-democratic regimes in the region. These findings pave the way for further research and targeted policy development tailored to the specific needs of SSA.

The results from this study call for a reconsideration of how we understand the dynamics of democratization in developing regions, particularly in SSA. The negative relationship between perceived government performance and democratic support could indicate a growing disillusionment with the ability of democratic systems to deliver tangible socio-economic benefits. In rapidly urbanizing environments, where expectations for government services and economic opportunities may be higher, this disillusionment appears to be even more pronounced.

The study’s findings also highlight the importance of considering context-specific factors when examining democratic attitudes. The unique historical, cultural, and socio-economic conditions of SSA countries may be shaping citizens’ perceptions of democracy in ways that differ from other regions. For instance, the legacy of authoritarian rule, ongoing challenges with corruption, and persistent economic inequalities could be influencing how citizens evaluate the performance of democratic governments and their overall support for democratic systems.

From a policy perspective, these results underscore the need for governments and international development organizations to pay closer attention to the quality of governance and service delivery, particularly in urban areas. Improving socio-economic conditions and citizens’ perceptions of government performance may be crucial not only for development outcomes but also for maintaining and strengthening support for democratic institutions. Policymakers may need to focus on addressing the specific challenges faced by urban populations, such as inequality, unemployment, and inadequate infrastructure, to prevent erosion of democratic support in rapidly urbanizing contexts.

However, it is important to note the limitations of this study. While the model shows statistically significant relationships, its overall explanatory power is relatively low, indicating that other factors not included in the analysis may play substantial roles in shaping support for democracy. Future research should explore additional variables that might influence democratic attitudes in SSA, such as education levels, ethnic diversity, or exposure to democratic norms through media and civil society. Longitudinal studies could also provide valuable insights into how these relationships evolve over time, particularly as countries continue to urbanize and develop economically.