Abstract

This study examines the gender dynamics in urban space usage within the historic city center of Tebessa, Algeria, exploring how cultural factors and street networks influence gender-specific pedestrian behavior and land use patterns. Using a multidisciplinary approach combining space syntax techniques, GIS analysis, and behavioral data collection, we analyzed the relationships between street networks, land use attractors, and gender-differentiated pedestrian flows. Key findings reveal significant differences in spatial navigation patterns between men and women, influenced by cultural norms and gender-specific land use distribution. Women’s movement is more constrained and focused on specific attractors, while men navigate the entire urban system more freely. The study also highlights the impact of “edge effects”, where extramural attractors strongly influence intramural gender movement, particularly for women. These gender-specific patterns often override street network influences predicted by traditional space syntax theories. Our research contributes to the understanding of sustainable urban development in culturally rich contexts by demonstrating the need for gender-inclusive planning that considers local cultural practices. The findings have important implications for urban planners and policymakers working to create more equitable and functional historic city centers while preserving cultural heritage and addressing gender-specific needs.

1. Introduction

Historic city centers in Algeria present unique challenges for sustainable urban development, particularly in terms of gender-specific space usage and pedestrian flow. The city center of Tebessa, with its rich tapestry of Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, French, and Arab influences, offers an ideal case study to explore these dynamics. This research investigates the intricate relationships between street networks, land use, and gender-specific pedestrian flow in Tebessa’s historic core, with a particular focus on how cultural factors shape these interactions.

Recent research emphasizes the critical role of gender dynamics in shaping urban mobility and gender-specific behavior, especially in culturally rich contexts. Horn (2024) highlights walking as a transformative approach to developing inclusive urban mobility systems, advocating for pedestrian-centric designs that consider social and ecological factors [1]. Similarly, Mazzulla et al. (2024) investigated how men and women perceive pedestrian path attractiveness differently, underscoring the need to account for gender-specific preferences in urban planning [2]. Ramezani et al. (2024) provided a critical perspective on walkability, questioning when promoting walkable environments may not be beneficial, particularly in culturally rich contexts like historic city centers [3].

For instance, Askarizad et al. emphasized the need for integrated approaches that consider both street networks and social factors in enhancing the sociability of public urban spaces [4]. Similarly, Yang and Qian (2023) explored the integration of street network analysis and functional attractors in capturing pedestrian movement patterns, though their research did not specifically address gender dynamics [5,6]. Pedestrian movement in urban spaces is influenced by various factors, both environmental and user related [7,8]. Recent research has emphasized the importance of understanding pedestrian behavior for enhancing urban design and ensuring the durability of spaces [9,10,11,12].

This study aims to explore these themes within the context of Tebessa’s historic city center by examining the interplay between urban morphology, land use, and gender-specific pedestrian flows, by examining how gender influences navigation patterns, space perception, and land use in a North African urban context. Specifically, we seek to answer the following research questions:

How do gender-specific cultural norms and practices influence pedestrian movement and space usage patterns in Tebessa’s historic city center?

To what extent do land use patterns and the distribution of attractors reflect and reinforce gender-specific space usage?

Despite the growing body of literature on street networks, pedestrian behavior, and gender dynamics in urban space usage, several key gaps remain: (a) Limited comprehensive research integrating urban morphology, land use, pedestrian flow, cultural factors, and gender dynamics, particularly in historic city centers with complex cultural contexts such as North African or Islamic settings; (b) insufficient in-depth analysis of how gender influences navigation patterns, space perception, and land use in culturally rich urban environments; (c) lack of research on how gender-specific perceptions of pedestrian path attractiveness influence navigation choices and overall urban space usage; (d) inadequate exploration of the applicability and limitations of walkability approaches in certain urban environments, especially those with rich historical and cultural backgrounds; (e) the need for integrated approaches that consider spatial configuration, land use attractiveness, cultural factors, and gender dynamics in understanding pedestrian behavior; and (f) limited studies on the interaction between intramural and extramural factors affecting pedestrian behavior in historic walled city centers, particularly from a gender perspective.

This research aims to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of gender dynamics in urban environments, particularly in contexts where cultural factors significantly shape spatial behaviors. It adopts a multidisciplinary approach, combining space syntax techniques, GIS analysis, and behavioral data collection, to provide a comprehensive picture of gender-specific urban dynamics.

The findings of this study have important implications for urban planners and policymakers working to create more inclusive, functional, and culturally sensitive urban environments in historic city centers. By understanding how gender influences space usage and pedestrian flow, we can develop strategies that balance preserving cultural heritage, with the need for equitable access to urban resources and opportunities.

Literature Review

Recent studies have highlighted the complex relationships between urban form, land use, and pedestrian behavior in historic urban contexts, particularly emphasizing the role of cultural factors and gender dynamics. The existing literature underscores various aspects of these dynamics in urban environments. Horn (2024) advocates for a shift towards pedestrian-centric urban mobility systems that promote inclusivity and sustainability [1]. This aligns with Mazzulla et al.’s (2024) findings that men and women perceive pedestrian path attractiveness differently, suggesting urban planners must consider these gender-specific preferences when designing public spaces [2]. However, Ramezani et al. (2024) critically reviewed walkability approaches, cautioning that promoting walkable environments may not always yield positive outcomes, especially in culturally diverse settings where traditional metrics may not fully capture local needs [3]. Askarizad’s systematic review on the application of space syntax to enhance sociability in public urban spaces further emphasizes the need for integrated approaches that consider both street network configurations and social factors [4].

Similarly, Yang and Qian explored the integration of street network analysis and functional attractors in capturing pedestrian movement patterns, highlighting the importance of considering both spatial and functional aspects in urban design [6].

The influence of gender on urban space usage has gained increasing attention in recent years. Rampaul and Magidimisha-Chipungu examined the importance of gender mainstreaming in urban planning to promote inclusive cities, emphasizing the need to include women in decision-making processes and consider their unique experiences in urban spaces [13]. Similarly, Ariane and Emília Malcata emphasized the importance of women’s perception and use of public spaces and initiatives to promote gender equality [14].

This aligns with our study’s focus on gender-specific navigation patterns in Tebessa’s historic city center. Cultural factors play a significant role in shaping urban space usage, particularly in traditional Islamic contexts. Bagheri [15] explored how cultural norms and gender roles influence the use of public spaces in Middle Eastern cities (Nazgol). Recent studies have also explored the role of gender and culture in shaping public space behaviors and intentions. Jalalkamali and Doratli’s research on public space behaviors in Kerman, Iran, provides valuable insights into how gender influences urban space usage in a cultural context [16].

The concept of “edge effects” in walled historic centers has been relatively unexplored in recent literature. However, our study addresses this gap by examining how extramural attractors influence intramural pedestrian movement, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of urban dynamics in historic contexts. Fezzai assessed patterns of spatial transformations in three historic city centers in Algeria, highlighting the need for context-specific approaches to urban analysis and planning [17].

This research supports our multidisciplinary approach, combining space syntax techniques, GIS analysis, and behavioral data collection to provide a comprehensive understanding of the urban dynamics at play. Al Sayed et al. (2022) modeled street network growth in historic cities, emphasizing the importance of understanding long-term urban evolution in planning for sustainable futures [18].

This aligns with our study’s consideration of the historical layers influencing Tebessa’s urban fabric. Garcia-Blanco et al. (2023) explored the adoption of nature-based solutions in urban planning, emphasizing the importance of considering the broader urban context in sustainable design strategies [19].

While this study does not directly address environmental factors, it underscores the importance of holistic approaches to urban planning, which we incorporate by considering cultural and gender dimensions alongside street networks.

Limited studies on the interactions among street networks, land use, and pedestrian flow in historic city centers with complex cultural contexts, particularly in North African settings, remain neglected by researchers. Additionally, there is an insufficient exploration of gender-specific navigation patterns and the influence of extramural attractors on intramural pedestrian movement in walled historic centers. Our study aims to address these gaps by providing a comprehensive analysis of the relationships between street networks, land use attractors, and pedestrian flow in Tebessa’s historic city center while considering the unique cultural and gender-related aspects of the region.

2. Materials and Methods

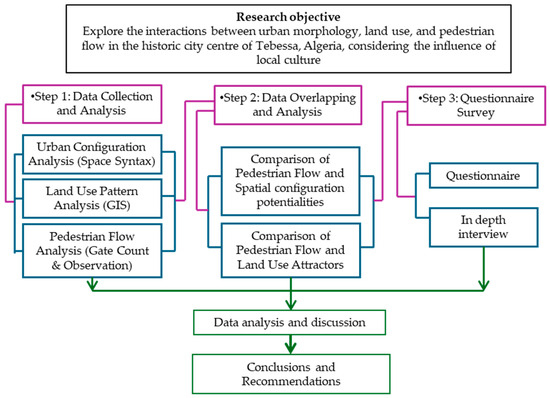

This research adopts a multidisciplinary approach to analyze the sustainable urban dynamics of Tebessa’s historic city center. The methodology consists of three main steps (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Methodology flowchart by authors.

Step 1: Data Collection and Analysis

- Urban Configuration Analysis:

Space syntax techniques were used to predict potential pedestrian behaviors highlighting gender-specific movement potentials and creating an axial map of the city center focusing on connectivity, integration, and choice. This analysis helps understand the sustainable potential of the urban layout in promoting walkability and social interaction [4].

- b.

- Land Use Pattern Analysis:

A GIS-based land use map was created to detect hotspots and clustered functions that may serve as attractors. This analysis aids in understanding the distribution of urban functions and their potential impact on sustainable urban development, with a special focus on gender-specific attractors and their distribution [20].

- c.

- Pedestrian Flow Analysis:

Data were collected using the gate count technique and observation of user density, with a focus on gender-specific patterns. This analysis helps identify areas of high pedestrian activity and potential conflicts, focusing on male and female presence in different zones of the urban layout [21].

Step 2: Data Overlapping and Analysis

The data analyzed were overlapped to understand the relationships between street network, land use, and pedestrian flow. This integrated analysis approach aligns with recent research by Yang and Qian [6], who emphasized the importance of considering both street networks and functional attractors in capturing pedestrian movement patterns. This analysis is focused on gender differences in spatial usage patterns and the comparison of gender-specific pedestrian flows with land use attractors.

Step 3: Questionnaire Survey and In-Depth Interviews

A questionnaire survey was conducted to investigate the highlighted issues, with a focus on understanding the cultural and gender-specific experiences and perceptions of urban space, in addition to in-depth interviews with both male and female respondents to gather qualitative data on their perceptions of safety, comfort, and inclusivity in different areas of the city center and how gender-segregated spaces impact their daily activities and social interactions.

The data collection for this study was conducted over a one-week period from 22–29 March 2024. This timeframe was specifically chosen to represent average climate conditions in Tebessa, avoiding the potential effects of extreme temperatures on pedestrian behavior. The survey and interviews were carried out on all days of the week, including both working days and weekends, to capture a comprehensive picture of urban space usage patterns. Pedestrian counts were performed at regular intervals throughout the day, with 10-min counts conducted every 2 h from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM. This approach ensured that the data collected represented a wide range of daily activities and movement patterns across different times and days of the week.

Structure of the Questionnaire:

The questionnaire was designed to gather comprehensive data on gender-specific experiences and perceptions related to urban space usage. It is divided into four parts:

- Personal Data: Collect demographic information to understand the background of respondents, including age, gender, and familiarity with the city center.

- Navigation Information: Gather details on respondents’ navigation objectives, frequency of visits, preferred times for visiting, and modes of transportation used to access the city center.

- Factors Influencing Navigation: Identify key factors that influence route choice, including safety perceptions, cultural norms, and the presence of specific land use attractors.

- Gender-Specific Experiences: Explore how gender influences navigation preferences, comfort levels in different areas, and perceptions of safety within the urban environment.

Sample Size and Selection:

The sample consists of 120 adults, with equal representations of men and women (60 each). This balanced sample ensures statistical significance while allowing for a diverse range of perspectives across different age categories and user objectives. The selection process involved the following:

- Statistical Power: A sample size of 120 provides sufficient power to detect medium effect sizes in statistical analyses.

- Representativeness: This size allows for capturing a broad spectrum of experiences related to gender and navigation in the historic city center.

- Feasibility: This number is manageable for the research team to conduct and analyze within the study timeframe.

In-Depth Interviews:

To gather qualitative data on cultural influences, in-depth interviews were conducted with a subset of 20 respondents (10 men and 10 women). These interviews explored the following:

- Personal experiences of navigating the city center.

- The impact of gender roles on space usage and movement patterns.

- Perceptions of gender-segregated spaces and their implications for social interaction.

Before participating in the survey or interviews, all respondents received an informed consent form detailing the following:

The purpose of the study;

The voluntary nature of participation;

The right to withdraw at any time without consequences;

Confidentiality measures to protect participants’ identities;

How data were to be used and stored.

Participants were required to sign this form before engaging in the study.

Sampling Strategy and Demographic Considerations:

Our sample of 120 respondents (60 women and 60 men) was designed to provide a balanced gender representation. However, we acknowledge that this sampling strategy has limitations. The study did not control age or occupation, which may influence movement patterns and perceptions of urban space. Future research should consider a more stratified sampling approach to account for these demographic variables.

Potential impacts of our sampling strategy include the following:

Age bias: Younger and older adults may have different mobility patterns and perceptions of safety, which could influence their space usage.

Occupational bias: The time of day for data collection (8 AM to 4 PM) may have overrepresented certain occupational groups while underrepresenting others, potentially skewing the observed movement patterns.

Socioeconomic factors: The study did not account for socioeconomic status, which could influence access to transportation and patterns of urban space usage.

These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and could be addressed in future studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of gender-specific urban dynamics in Tebessa’s historic center.

The integration of space syntax, GIS, and behavioral observation techniques provides a more comprehensive understanding of gender-specific movement patterns than traditional approaches. Space syntax analysis reveals the potential for movement based on urban configuration, while GIS mapping of land use patterns identifies gender-specific attractors. Behavioral observation then validates and refines these predictions with real-world data. This combined approach allowed us to identify discrepancies between predicted and actual movement patterns, revealing the influence of cultural factors that might be overlooked by spatial analysis alone. For example, the integration of these methods helped us identify how women’s movement patterns deviate from space syntax predictions due to cultural norms and safety concerns, a finding that would not be apparent using any single method.

Study Area: The City Center of Tebessa

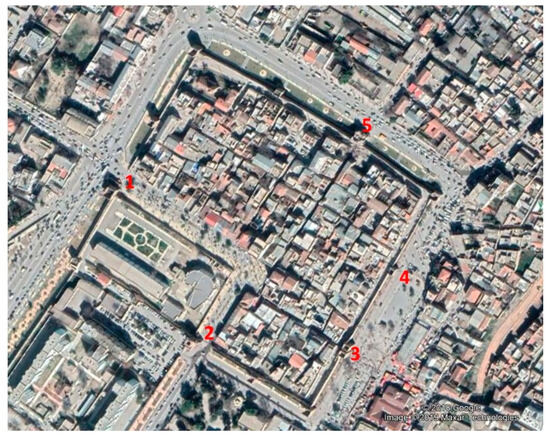

The city center of Tebessa represents a heritage of high historical value; it includes buildings of different historical periods, Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, French, and contemporary, surrounded by a Byzantine wall. Several historical monuments are on the site, demonstrating a rich history. The Byzantine wall is a rectangular shape of around 290 m to 250 m, surrounding an area of 72,533 m2. Five gates allow access to intramural space from the four sides; they also allow crossing the city center to reach other sides, which creates crowded space (Figure 2) mainly in central streets that link the different gates.

Figure 2.

The city center of Tebessa, showing the five gates (authors, 2023).

Gate 1 (Gate of Constantine) leads to the main axis of the city and the administrative zone. Gate 2 leads to car parking of the city center. Gates 3 and 4 are the main access points to the commercial zone (markets), while gate 5 (Caracalla triumphal arch) leads to a housing neighborhood with several commercial stores.

3. Analysis and Results

3.1. Step 1: Data Collection and Analysis

3.1.1. Land Use Pattern Analysis

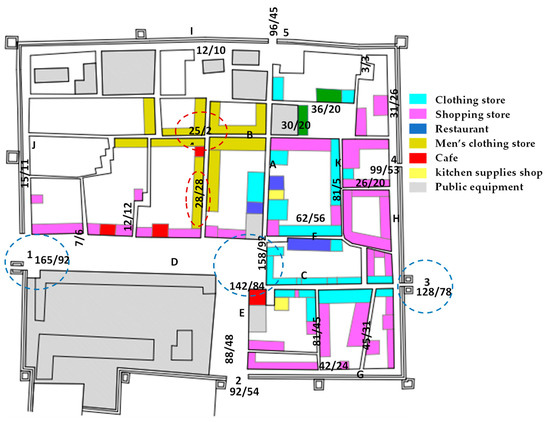

Most of the intramural buildings include shops on their ground floors. Figure 3 illustrates the land use of the intramural zone of the city center; it shows a high concentration of shopping stores, mainly in the central zone and the main streets that link the center to the gates. The GIS-based land use map (Figure 3) highlights gender-specific attractors and their distribution:

Figure 3.

Land use in the intramural city center of Tebessa (authors, 2023).

- Men’s clothing shops clustered in the left zone near the main axis (Street B).

- Women’s clothing and kitchen supply stores concentrated along streets A, C, D, and K.

- Cafes and restaurants, primarily male-dominated spaces, clustered along street F.

This gender-specific distribution of attractors significantly influences movement patterns and space usage for both men and women.

3.1.2. Urban Configuration Analysis

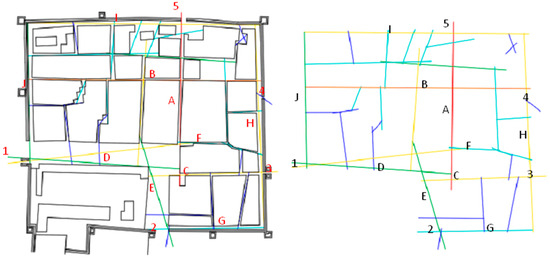

A space syntax analysis utilized DepthmapX 0.5 software to create an axial map of Tebessa’s city center. This analysis included measures of connectivity, integration, and choice, while also considering gender-specific movement potentials.

To facilitate reading the axial map, we attributed codes to the different gates and the main axes of the intramural city center, as shown in Figure 4. The selection of the studied streets is based on their importance, according to the three main parameters of this study: spatial properties, land use distribution, and pedestrian flow. Figure 4 shows the axial map of the city center, while the results of syntactic measures are shown in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Axial map of intramural (city center of Tebessa), axial integration (realized by authors).

Table 1.

Syntactic measures for the study area.

The axial map (Figure 4) shows the values of axial integration for each axis, representing a street in the city center. The red color represents the highest values, then the orange, yellow, green, and blue colors represent the lowest values. It is important to note that the space syntax measures are on the restricted walled area, but it is connected with the rest of the city via several gates. The study area is embedded in a larger urban environment that has much influence on pedestrian movement inside.

The analysis shows (Table 1, Figure 4) that the most connected spaces have the highest values of integration and choice (red color). According to Hillier’s theory of natural movement [22,23], the analysis revealed the following:

- Streets A and B exhibited the highest integration and choice values, indicating significant potential for both male and female movement.

- Central plazas (E and D) demonstrated moderate syntactic values, suggesting a potential for mixed-gender static behavior.

- Peripheral streets showed lower syntactic values, which may limit women’s movement due to cultural norms.

3.1.3. Pedestrian Flow Analysis:

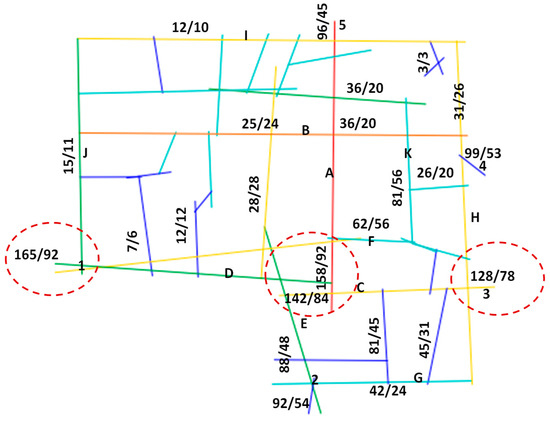

The behavioral map (Figure 5) was realized through the gate count and observations of pedestrian flow in the intramural urban space; the map is represented as follows (all pedestrians/male pedestrians) for each gate or street.

Figure 5.

Behavioral map showing different axes of urban space and gate counts represented as average/men.

Data collection was performed during a week to cover all days (working days and weekends), selecting 27 points representing the five gates and axes, and counting pedestrians for ten minutes every 2 h (from 08 am–10 am–12 pm–2 pm to 4 pm). The results are represented in Table 2 and Figure 5.

Table 2.

Pedestrian flow for different selected points with gender rates.

The behavioral map shows a high density of pedestrians in the central space; streets A, C, and D show the highest rate of pedestrian flow, linking the central space to gates 1, 3, and 5. Peripheral streets show low values. The gates present a balanced flow except for doors 1 and 3, which have very high values. They lead to important areas in the city: gate 1 opens towards Constantine street, a primary artery in the city and commercial street; gate 3 leads to the large popular market, which makes the intramural a transition zone crossed by pedestrians to reach other zones.

Behavioral maps illustrate distinct movement patterns for each gender. Key observations included the following:

- Pedestrian density was high in central spaces, particularly on streets A, C, and D.

- Women’s movement was more restricted, focusing on specific zones while avoiding male-dominated areas like street B.

- Significant gender disparities in peripheral street usage were noted, with women showing very low or zero values.

3.2. Step 2: Data Overlapping and Analysis

Comparing the different analysis results highlights the relations between spatial potentialities of the studied urban space, land use attractivity, and pedestrian flow. The superposition of the three layers of analysis allows us to define any possible correlations between them.

3.2.1. Gender Differences in Spatial Usage Patterns

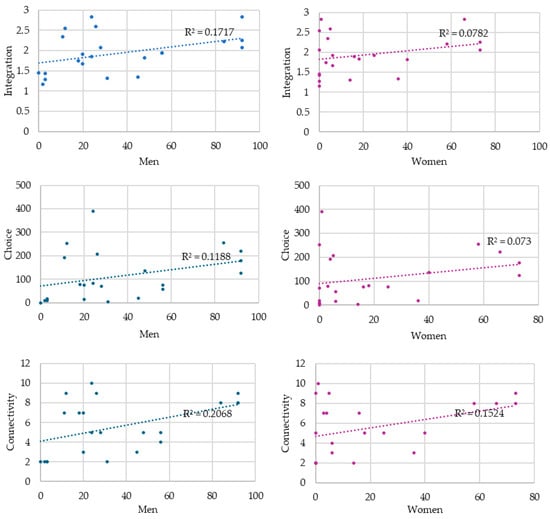

Analysis of the correlation between syntactic measures and pedestrian movement revealed weak relationships for both genders showed the following:

- Integration: Men (0.17), Women (0.07);

- Choice: Men (0.11), Women (0.07);

- Connectivity: Men (0.20), Women (0.15).

Figure 6 displays correlation graphs showing dispersed values with low Pearson’s coefficients for all syntactic parameters. This suggests that configurational parameters alone do not strongly predict pedestrian movement, indicating other factors influencing spatial usage patterns.

Figure 6.

Correlations of gender-specific behavioral data and configurational measures.

The overlapping map highlights pedestrians’ most frequently used streets, A, C, D, and E. Street A exhibits high configurational measures and high pedestrian use, while streets C, D, and E show moderate configuration values but high usage rates. Notably, street B has high syntactic values but low pedestrian use.

Significant edge effects were observed, with pedestrian flow concentrated near gates and connecting streets. This suggests that extramural activities and gate positions have a stronger influence on movement than intramural spatial properties.

Gender-specific patterns emerged, with women notably absent from streets with high or medium syntactic values, instead favoring routes with lower values. This observation raises questions about the factors driving women’s urban space usage in the city center.

Overlaying gender-specific behavioral maps with axial and land use data revealed the following distinct patterns:

- Men utilized diverse urban spaces, including high syntactic value areas and male-specific attractors.

- Women’s movement primarily occurred in central areas with female-specific attractors, often avoiding high-value areas dominated by male-oriented uses.

3.2.2. Gender-Specific Pedestrian Flows and Land Use Attractors

Land use attractors strongly influence pedestrian behavior, with density and gender distribution closely linked to attractor locations. Ground-floor commercial activities, particularly clothing stores, dictate pedestrian movement patterns. Streets lined with clothing stores experience high pedestrian traffic, while those lacking ground-floor commercial activity see minimal movement. Gender-specific space usage is heavily influenced by land use patterns:

Women predominantly navigate central areas and streets with general stores (A, D, C), avoiding streets dedicated to men’s clothing stores (B) and those dominated by restaurants and cafes (F). Men traverse the entire urban system more freely.

Most women utilize streets A, C, D, E, and K, which are linked to intramural gates and surrounded by shops catering to clothing or kitchen supplies.

This pattern suggests a form of urban space privatization reinforced by land use. Cultural norms further influence this segregation, with some stores restricting male entry unless accompanying women.

Figure 7 illustrates the overlap between land use and pedestrian behavior, highlighting these gender-specific patterns.

Figure 7.

Overlapping the three layers: street networks (represented by axial integration), land use, and pedestrian navigation (authors, 2023).

In conclusion, local cultural practices significantly impact the placement of land use attractors, which in turn govern pedestrian flow patterns regardless of street networks. Only streets connected to gates maintain a consistent relationship between street networks, land use attraction, and pedestrian movement.

Gender-specific pedestrian flows correlate strongly with land use distributions:

- Women’s movement aligns closely with women’s clothing and household goods shops.

- Men’s movements are more evenly distributed but concentrate around men’s clothing shops, cafes, and restaurants.

- Both genders show high movement rates in mixed-use areas, especially near gates 1 and 3.

3.3. Step 3: Questionnaire Survey and In-Depth Interviews

The analysis revealed an unexpected discrepancy between street networks, land use, and pedestrian flow, influenced by local culture and gender segregation. To investigate these findings further, a questionnaire survey and in-depth interviews were conducted.

Questionnaire Survey

A sample of 120 respondents (60 women and 60 men) completed a three-part questionnaire during their visit to the city center. The survey structure was based on Weisman’s method [24], focusing on the following:

- Self-reported wayfinding behavior and urban space knowledge.

- Navigation patterns, including destinations and routes.

- Impact of land use attractors and gender presence on spatial choices.

The questionnaire survey revealed significant insights into gender-specific behaviors and perceptions in Tebessa’s historic city center (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of the questionnaire survey handed to 120 respondents (60 men, 60 women).

- Urban space knowledge:

- Of the men, 83.33% reported good knowledge of the urban settings.

- Only 35% of women reported good knowledge, with 53.33% reporting average knowledge. This indicates men are more familiar with the entire site, while women’s knowledge is restricted to areas serving their needs.

- b.

- Navigation patterns:

- Of the women, 80% had precise intramural destinations, compared to 60% of men.

- Of the men, 40% crossed through to reach external destinations, versus only 20% of women.

- c.

- Navigation influences:

- Of the men, 73.33% were influenced by urban settings in their route choices.

- Of the women, 60% were attracted by specific commercial targets, particularly stores catering to women’s needs.

- d.

- Route choice factors:

- Men prioritized short distances and familiarity with routes.

- Women emphasized security as the main factor influencing their choices.

- e.

- Gender-specific space avoidance:

- Of the women, 55% reported avoiding male-dominated spaces like cafes and men’s clothing stores.

- Of the men, 58.33% stated they avoid female-oriented spaces, though these were fewer in the intramural zone.

- f.

- Accompanied vs. solo navigation:

- Of the women, 73.33% preferred accompanied visits, allowing them to navigate the entire urban space.

- Of the men, 80% preferred to navigate alone.

In-Depth Interview Insights:

- Cultural norms significantly affected women’s spatial choices, often limiting their access to certain areas.

- Men expressed greater comfort in navigating the entire urban space.

- Both genders acknowledged how gender-segregated spaces impact their movement patterns.

- Women reported feeling more secure and comfortable accessing male-dominated areas when accompanied by men.

- Cultural expectations and social norms played a significant role in shaping gender-specific movement patterns and space usage.

- These findings highlight the complex interplay between cultural factors, gender dynamics, and urban space usage in Tebessa’s historic city center, underscoring the need for gender-inclusive urban planning that considers local cultural practices.

4. Discussion

This study’s findings offer valuable insights into the complex interactions among street networks, land use, and pedestrian behavior in the historic city center of Tebessa, Algeria. The results both support and challenge existing theories in urban studies, particularly when viewed through the lens of sustainability.

The findings from this study resonate with the research of Horn [1], Mazzulla et al. [2], and Ramezani et al. [3]. The observed gender-specific navigation patterns in Tebessa’s historic center illustrate how local culture and land use distribution significantly impact pedestrian behavior. The preference of women for certain routes aligns with Mazzulla et al.’s findings [2] on path attractiveness, indicating that perceptions of safety and comfort play crucial roles in their navigation choices.

Moreover, the study’s results support Ramezani et al.’s critical perspective on walkability [3]; while promoting pedestrian-friendly environments is essential, it is equally important to consider when such approaches may not be effective or appropriate within culturally rich contexts like Tebessa. The findings suggest that urban planners should adopt a more flexible approach to walkability that incorporates local cultural practices and recognizes the unique challenges faced by different genders.

Our findings partially align with Hillier et al.’s theory of natural movement [22,25], which posits that urban configuration influences both pedestrian movement and the distribution of attractors. However, our study reveals a more nuanced relationship in the context of a historic city center with strong cultural influences. The low correlation between street network measures and pedestrian flow contradicts some previous studies [10,26,27] that found strong relationships between space syntax measures and pedestrian movement. This discrepancy might be explained by the unique characteristics of historic city centers, particularly those with strong cultural influences on spatial use.

The strong influence of land use attractors on pedestrian behavior, especially in gender-specific movement patterns, aligns with Vukmirovic’s emphasis on the role of attractors in pedestrian orientation [9]. Our findings also corroborate Zahrah and Lie’s research [28] on the importance of commerce as an attractor in creating dynamic pedestrian atmospheres.

The gender differences in spatial navigation observed in our study are consistent with research by Appleyard and Brown [29], who attributed such differences to biological, cultural, and social factors. Our findings particularly highlight the role of cultural factors in shaping gender-specific movement patterns, extending the understanding of these differences in a North African urban context.

Our study reveals that specific cultural variables significantly influence gender-specific movement and space usage in Tebessa’s historic center. Religious practices, such as gender segregation in certain public spaces, directly impact women’s movement patterns, often restricting their access to male-dominated areas like cafes and men’s clothing stores. Family roles also play a crucial part, with women’s movements often tied to household responsibilities, reflected in their preference for routes with access to grocery stores and household goods shops. The cultural expectation for women to be accompanied in public spaces, as indicated by 73.33% of female respondents preferring accompanied visits, further shapes their navigation patterns. These cultural norms often override spatial configuration in determining movement, explaining the weak correlation between space syntax measures and observed pedestrian flows for women.

Implications for Sustainable Urban Development:

The findings of this study highlight the need for sustainable urban development strategies that are inclusive, culturally sensitive, and gender-responsive in historic city centers like Tebessa. These insights align with and expand upon recent research in urban planning and sustainability:

- Cultural Sensitivity in Space Design: The strong influence of local culture on pedestrian behavior and land use distribution suggests that sustainable urban planning in historic centers should incorporate cultural considerations alongside street networks. This supports Ramezani et al.’s caution against applying universal walkability frameworks without considering local contexts [3]. It also aligns with Fezzai’s and García-Blanco et al.’s recent research [17,19,30], who emphasized the importance of adopting resilience thinking in urban planning, considering local contexts and user perspectives.

- Gender-Inclusive Planning: The marked differences in male and female navigation patterns highlight the need for gender-inclusive urban planning. This aspect is crucial for achieving UN Sustainable Development Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), particularly target 11.7 on providing universal access to safe, inclusive, and accessible public spaces. The observed gender-specific movement patterns underscore the importance of designing urban spaces that cater to the needs of both men and women. This aligns with Horn’s emphasis on walking as a transformative approach to fostering inclusive urban mobility systems [1]. Mazzulla et al.’s findings on gender differences in perceiving pedestrian path attractiveness further support the need for gender-sensitive design approaches [2].

- Balancing Preservation and Functionality: This study underscores the challenge of maintaining the historical integrity of city centers while addressing modern functional needs. This balance is essential for sustainable urban development, as highlighted by Fezzai [17] in his assessment of spatial transformations in historic Algerian city centers.

- Edge Effect Considerations: The significant influence of extramural attractors on intramural pedestrian flow suggests that planners should consider the wider urban context when designing for historic city centers. This holistic approach aligns with recent research by Yang and Qian [6], who emphasized the importance of integrating street network analysis and functional attractors in capturing pedestrian movement patterns.

- Flexible Land Use Policies: Given the dynamic nature of land use evolution observed in this study, urban policies should be flexible enough to accommodate changing needs while still maintaining the overall character and functionality of the historic center. This flexibility is crucial for long-term urban sustainability, as demonstrated by Al Sayed et al. [18] in their study of urban growth and street network evolution.

- Participatory Planning: The gender-specific findings highlight the importance of involving diverse stakeholders in the planning process, as suggested by Askarizad et al. [4] in their review of space syntax applications for enhancing sociability in public urban spaces.

- Sustainable Mobility: This study’s focus on pedestrian behavior supports Hillier et al.’s theory of natural movement [22], while also revealing the limitations of this theory in culturally rich contexts. This underscores the need for sustainable mobility solutions that consider both spatial configuration and cultural factors.

Broader Implications and Future Research Directions:

This study contributes to the growing body of research on sustainable urban design in culturally rich contexts. The findings highlight the need for more integrated approaches that consider street network, land use attractiveness, and cultural factors in understanding and planning for pedestrian behavior.

Future research could explore the following:

- Longitudinal studies to examine how pedestrian patterns and land use change over time in response to urban interventions, building on the research of Askarizad et al. [4] on enhancing sociability in public urban spaces;

- Comparative studies across multiple historic centers in different cultural contexts to assess the generalizability of these findings;

- The development of quantitative measures to assess the impact of specific cultural practices on urban space use, potentially integrating advanced technologies such as GPS tracking or mobile phone data for more comprehensive pedestrian movement analysis;

- The economic and environmental impacts of current land use patterns and potential changes, considering both intramural and extramural effects;

- The role of participatory planning processes in creating more sustainable and culturally sensitive urban environments, involving local stakeholders more extensively in research and decision-making processes;

- The impact of climate change and environmental factors on pedestrian behavior and sustainable urban design in historic city centers, an aspect not extensively covered in this study but crucial for long-term urban resilience.

5. Conclusions

This research explored the intricate relationships between street networks, land use, and gender-specific pedestrian flow in the historic city center of Tebessa, Algeria. Using an anthropo-spatial approach combining space syntax techniques, GIS analysis, and behavioral data collection, several key findings emerged:

Gender-specific navigation patterns: Significant differences were observed in how men and women navigate and use urban spaces in Tebessa’s historic center. These patterns are strongly influenced by cultural norms and gender-specific land use distribution.

Cultural influence on spatial usage: Local cultural practices play a crucial role in shaping both the location of attractors and pedestrian flow patterns, often overriding the influence of street networks predicted by traditional space syntax theories.

Land use attractors and gender segregation: The distribution of gender-specific commercial spaces significantly impacts overall pedestrian flow and reinforces gender segregation in space usage.

Edge effects on gender-specific movement: Extramural attractors strongly influence intramural pedestrian movement, particularly for women, highlighting the importance of considering the broader urban context in gender-inclusive design.

These findings have important implications for sustainable and inclusive urban planning in historic city centers:

- Gender-inclusive design: Urban planners must consider the distinct needs and behaviors of both men and women when designing public spaces and distributing land uses.

- Cultural sensitivity: Sustainable urban development in historic centers should integrate local cultural practices while promoting more equitable space usage.

- Balancing preservation and inclusivity: There is a need to find innovative ways to preserve the historical urban fabric while adapting it to support more gender-inclusive practices.

- Participatory planning: Involving both men and women in the urban planning process is crucial for creating spaces that meet the needs of all users.

This study contributes to the growing body of research on gender and urban space by providing insights into the complex interplay between street networks, land use, and cultural factors in shaping gender-specific urban dynamics. Future research could extend this approach to multiple historic centers across different cultural contexts to assess the generalizability of these findings and explore potential interventions for creating more inclusive urban environments.

By addressing these gender-specific dynamics, urban planners and policymakers can work towards creating more equitable, functional, and culturally sensitive urban spaces that respect historical heritage while meeting the diverse needs of contemporary urban populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F. and A.M.; methodology, S.F. and A.M.; software, S.F.; validation, S.F. and A.M.; resources, S.F. and A.M.; data curation, S.F. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F., L.T.D. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, S.F., L.T.D. and A.M.; visualization, S.F. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Julian, H. Walking as an Approach to the Socially-Ecological Transformation of Inclusive Urban Mobility Systems: An Explorative Case Study Involving Disabled People in BERLIN; SP III 2024-602; Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB): Berlin, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/299230 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Gabriella, M.; Laura, E.; Carmen, F. Do women perceive pedestrian path attractiveness differently from men? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 179, 103890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Moghadam, S.E.E.R.M.; Rahmani, E.K.; Campisi, T. A Review of Walkability Criticism: When Is the Walkable Approach Not a Good Idea? Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Askarizad, R.; Lamíquiz, P.; Garau, C. The Application of Space Syntax to Enhance Sociability in Public Urban Spaces: A Systematic Review. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Wayfinding Behaviour in Unfamiliar Environment During Evacuation: An exploratory Study Based on Driving Simulator. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2015. Available online: https://repository.tudelft.nl/record/uuid:a4c9eae7-6b2e-4947-8c33-596e1f4446fa (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Yang, C.; Qian, Z. Street network or functional attractors? Capturing pedestrian movement patterns and urban form with the integration of space syntax and MCDA. Urban Des. Int. 2022. Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumenir, Y.; Georges, F.; Valentin, J.; Rebillard, G.U.Y.; Dresp, B. Wayfinding through an unfamiliar environment. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2010, 111, 829–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoud, S.; Bada, Y.; Cutini, V. The impact of the urban structure on the public squares uses: A syntactic analysis. Case of Bejaia city, Algeria. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 10, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukmirovic, M.; Folić, B. Cognitive performances of pedestrian spaces. Facta Univ.—Ser. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2017, 15, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappu, H. Analyzing the spatial structure of the street network to understand the mobility pattern and land use: A case of an indian city, mysore. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2018, 11, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezbradica, M.; Ruskin, H. Understanding Urban Mobility and Pedestrian Movement; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Islam, S. Investigating Pedestrian Based Informal Economy and Its Impact on Walkability in Dhaka City. In Proceedings of the ARCASIA Forum 20—Architecture in a Changing Landscape, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2–7 November 2019; pp. 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rampaul, K.; Magidimisha-Chipungu, H. Gender mainstreaming in the urban space to promote inclusive cities. J. Transdiscipl. Res. South. Afr. 2022, 18, a1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariane, P.; Emília Malcata, R. Women in public spaces: Perceptions and initiatives to promote gender equality. Cities 2024, 154, 105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazgol, B. Mapping women in Tehran’s public spaces: A geo-visualization perspective. Gend. Place Cult. 2014, 21, 1285–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalalkamali, A.; Doratli, N. Public Space Behaviors and Intentions: The Role of Gender through the Window of Culture, Case of Kerman. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fezzai, S. Assessment of Patterns of Spatial Transformations A Comparative Study of Three Historic City Centres in Algeria. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 12, 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Al Sayed, K.; Hanna, S.; Penn, A. Urban growth: Modelling street network growth in Manhattan (1642–2008) and Barcelona (1260–2008). Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 949441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Blanco, G.; Navarro, D.; Feliu, E. Adopting Resilience Thinking through Nature-Based Solutions within Urban Planning: A Case Study in the City of València. Buildings 2023, 13, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heba, O.T.; Mark David, M.; Raffaello, F. Accessibility of green spaces in a metropolitan network using space syntax to objectively evaluate the spatial locations of parks and promenades in Doha, State of Qatar. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 58, 126892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.; Abdullah, M.; Ahmed, D.; Subaih, R. Pedestrians’ Microscopic Walking Dynamics in Single-File Movement: The Influence of Gender. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B.; Penn, A.; Hanson, J.; Grajewski, T.; Xu, J. Natural Movement: Or, Configuration and Attraction in Urban Pedestrian Movement. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1993, 20, 29–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HILLIER, B. Space is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Press, C.U., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick, J.A.; Lavrakas, P.J.; Kim, N. Survey Research. In Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psychology, 2nd ed.; Reis, H.T., Judd, C.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 404–442. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA; Sydney, Australia, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Monokrousou, K.; Giannopoulou, M. Interpreting and Predicting Pedestrian Movement in Public Space through Space Syntax Analysis. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk Hacar, Ö.; Gülgen, F.; Bilgi, S.; Kılıç, B. Accessibility Analysis of Street Networks Using Space Syntax. In Proceedings of the Conference: 7th International Conference on Cartography & GIS, Sozopol, Bulgaria, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zahrah, W.; Lie, S. People and Urban Space in Medan: An environment behaviour approach. Environ.-Behav. Proc. J. 2016, 1, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Appleyard, B. The meaning of livable streets to schoolchildren: An image mapping study of the effects of traffic on children’s cognitive development of spatial knowledge. J. Transp. Health 2017, 5, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María; Siamak, S.; Seyedasaad, H.; Hall, C.M.; Boshra, M.; Fernando, A.-G.; Macías, R.C. Breaking boundaries: Exploring gendered challenges and advancing equality for Iranian women careers in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2024, 103, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).