1. Introduction

The government reforms introduced through Vision 2030 in 2016 have transformed urban planning in Saudi Arabia, emphasizing decentralization and localized planning. A key component of these reforms is Local Participatory Urban Planning, aimed at actively engaging local communities, urban planners, and policymakers in shaping urban environments [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This approach enhances collaboration, transparency, and public participation, ensuring that urban planning processes align with community needs and aspirations [

5,

6,

7]. However, while Vision 2030 promotes decentralized and local participatory urban planning, its implementation has raised political, social, and ethical challenges. Concerns persist over the displacement of some communities, particularly in large-scale mega projects where relocations have taken place without sufficient public input [

8,

9,

10,

11]. This situation underscores a fundamental tension between the state’s top-down development strategies and its stated goal of fostering local participatory urban planning, often leading to the exclusion of some communities from urban planning processes [

3,

12].

Scholarly discussions highlight the complexities of balancing centralized governance with participatory urban planning. For instance, Saudi authorities have relocated some community members to make way for urban and development projects in NEOM, collaborating with global firms to construct a futuristic city. An in-depth analysis of these projects is beyond the scope of this paper; hence, we invite readers wishing to find out more to refer to relevant works [

13]. Although the local community does not legally own the land, the government, as Shihabi notes [

14], provided compensation exceeding market value, alongside new housing and additional benefits, such as scholarships, for those displaced. However, Moshashai, Leber, and Savage [

15] argue that while Vision 2030 has pursued economic reform, it sometimes overlooks social consequences, particularly the lack of inclusive governance mechanisms. These circumstances illustrate the challenge Vision 2030 faces in maintaining established power hierarchies while promoting bottom-up decision-making—a critical factor in achieving its objectives.

Building on these developments, the National Transformation Program [

16] played a pivotal role in reshaping urban planning policies in Saudi Arabia by introducing comprehensive reforms that reshaped urban development and governance, laying the foundation for the eventual realization of Vision 2030. This vision emphasizes decentralizing governance and increasing public participation in decision-making processes. The shift toward local participatory urban planning aimed to transition from a centralized model to a participatory system, with a strong emphasis on sustainability in urban development [

17].

In line with these changes, Vision 2030 strives to balance modernization—including economic diversification and participatory governance—with the preservation of cultural and governance traditions [

16,

18]. These initiatives highlight the role of institutions in facilitating public participation in planning processes [

19]. This shift has significantly influenced urban governance and planning in Saudi Arabia [

20]. A range of initiatives, including public hearings by the Asir Development Authority and participatory workshops at the municipal level in Dammam, Khobar, Jeddah, and Riyadh, exemplifies this transformation [

18,

21,

22,

23]. While these efforts have enhanced public participation and transparency, challenges remain, such as limited influence on decision-making, representation biases, and implementation gaps [

16,

23,

24].

The existing literature provides differing perspectives on centralized governance in urban planning. Alshuwaikhat and Mohammed [

25] argue that centralized governance in mega projects, such as the comprehensive governance model developed by the Saudi Council of Economic and Development Affairs, effectively coordinates efforts and ensures systematic monitoring of progress toward strategic objectives. However, this top-down approach also raises concerns about the marginalization of public input. While Vision 2030 aims to enhance quality of life through various programs, scholars have raised ethical concerns about the implementation of these programs, particularly regarding public participation [

26,

27].

This paper explores the changes and developments in urban planning policy since Vision 2030’s implementation and analyzes the impact of these policies on participatory planning. Particular attention is given to the effects of regional empowerment and local participatory urban planning on participatory planning practices in Saudi Arabia. This paper is guided by the following central research question: How have recent policies impacted the transformation of local participatory urban planning? To explore this question, this study examines the evolution of policy changes and their practical effects on participatory urban planning dynamics at the local level.

To examine these policy transformations in greater depth, this study employs a comprehensive research approach. First, a literature review is conducted to examine contemporary urban planning policies in Saudi Arabia, providing a theoretical foundation for understanding participatory governance. Second, a document analysis is carried out, reviewing official reports and policy documents to trace legislative and strategic changes over time. Third, semi-structured interviews with urban planners and policymakers offer qualitative insights into the challenges and opportunities associated with participatory urban planning implementation. Finally, a public survey is employed to provide quantitative insights, capturing public perceptions regarding the accessibility, effectiveness, and regional disparities in participatory initiatives.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a review of the existing literature on regional policies, focusing on the establishment of Regional Development Authorities and the increasing need for local empowerment to facilitate participatory urban planning.

Section 3 discusses empowerment policies, particularly those introduced under Vision 2030, and their impact on urban planning transformation.

Section 4 outlines the conceptual framework guiding this study, while

Section 5 details the research methodology. This study’s findings and analysis are presented in

Section 6, followed by a discussion of key results in

Section 7, where comparisons are drawn with existing theoretical perspectives. Finally,

Section 8 concludes this paper with a summary of findings and their implications for participatory urban planning in Saudi Arabia.

2. Literature Review and Study Background

Recent policy changes in Saudi Arabia emphasize empowering municipalities and regional development authorities through increased collaboration among ministries and departments. Digital initiatives, such as Your Voice Is Heard, along with platforms like Balady and Istitlaa, aim to encourage public participation in urban planning. The Balady platform provides over 200 digital services related to municipal operations, city infrastructure planning, and urban design, enabling residents to report issues and contribute to urban enhancement efforts. Similarly, the Istitlaa platform serves as a unified electronic portal where individuals, private sector entities, and government agencies can provide feedback on proposed laws and regulations—including urban planning policies—before their approval, fostering a participatory approach in policymaking [

7,

28].

While these platforms promote inclusivity, their reach remains limited. Certain populations, particularly in rural areas or those with restricted technological access, are often excluded from the participatory process [

7,

28]. This limitation aligns with findings that participation levels remain low due to insufficient efforts to expand awareness and integrate marginalized groups [

29]. The digital divide raises concerns about the long-term sustainability of such platforms as genuine tools for inclusive participation.

These policy changes can be categorized into three key elements: strategic framework change, institutional change, and regulatory change. The strategic framework establishes goals, offering direction and guidelines that shape institutional and regulatory adjustments regarding vision, mission, and broad objectives [

30]. Institutional change involves creating new government structures, adapting existing ones, and establishing new institutions to support participatory planning [

31]. Regulatory change addresses challenges such as resistance, agenda-setting, and institutional inertia, influencing how goals are pursued in response to public attention, shifting institutional dynamics, or policy adjustments. These regulatory shifts often result in modifications to rules and decision-making processes [

32].

2.1. Overview of the Policy Changes Affecting Participatory Planning

The three primary areas of change include the strategic framework, which sets the goals and direction for urban development; institutional change, which involves the restructuring and adaptation of government bodies to support decentralization; and regulatory change, which modifies rules and decision-making processes to address new urban planning challenges and enhance public participation.

2.1.1. Strategic Framework

Vision 2030

Vision 2030 is a comprehensive national development strategy designed to transform Saudi Arabia by diversifying its economy and promoting urban sustainability. This ambitious initiative is implemented through various realization programs, as outlined in

Table 1 [

33]. While the vision promotes empowerment and sustainable development programs, critics have noted that implementing parts of it can have unintended consequences, including displacement and the restriction of public participation under centralized governance in some new urban mega projects [

3,

8,

9,

10,

12]. Furthermore, Moshashai, Leber, and Savage [

15] argue that the National Transformation Plan and Saudi fiscal reforms prioritize economic growth over inclusive governance, further complicating efforts to integrate genuine public participation into urban planning processes.

Alshuwaikhat and Mohammed [

25] contend that centralized governance in mega projects, such as the comprehensive governance model developed by the Council of Economic and Development Affairs, can effectively coordinate efforts and ensure the systematic monitoring of progress toward strategic objectives like those outlined in Vision 2030. However, this top-down approach also raises concerns about its potential to marginalize public input. The vision aims to enhance the quality of life through various programs; however, ethical concerns about how these programs are implemented, particularly in relation to public participation, have been raised [

26,

27].

Smart Sustainable Cities Framework

Saudi Arabia is undergoing a major transformation aligned with its Vision 2030 and the National Transformation Program 2020. The Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs (MoMRA) has ambitious plans to establish 10 smart cities across the country, including both newly planned economic cities and existing urban centers. However, the development of these cities raises ethical concerns, including the displacement of local populations and a lack of transparency in decision-making processes [

8,

12,

27,

34,

35]. While the goal is to diversify the economy and attract foreign investment, it is essential to examine how these developments impact communities, particularly in terms of social equity and public participation, as these are often overlooked in the broader narrative of modernization [

25,

36].

A 2015 study assessed the readiness of 17 major cities in Saudi Arabia for this transformation [

15,

34]. The study identified Makkah and Riyadh as initial targets for completion by the end of 2018, followed by Jeddah, Al-Madinah, and Al-Ahsa by 2020. The transformation began as both Makkah and Riyadh made significant strides toward smart city development by 2018, with the remaining cities advancing by 2020 through the support of various government initiatives [

35,

37]. Additionally, projects like the Yanbu Industrial Smart City and NEOM underscore Saudi Arabia’s commitment to integrating smart technologies across both industrial and futuristic city developments [

33].

As Saudi Arabia advances its ambitious smart city initiatives, the Smart Sustainable Cities Framework (SSCF) plays a critical role in driving this technological transformation [

38]. This framework represents a deliberate shift toward an integrated urban development strategy, aligning with the ambitious goals outlined in Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and the National Transformation Program 2020. The SSCF in Saudi Arabia expands human, social, and environmental capital investments in urban areas by incorporating not just technology but also local participatory urban planning and decision-making [

38]. It actively supports the implementation of smart, sustainable city outcomes, helping to achieve the Future Sustainable Cities Plan (FSCP) within the broader context of Vision 2030 and government policy. The framework outlines Stakeholders’ Management Measures (SMM), Citizens’ Participation Level (CPL), and Citizens’ Participation Recruitment (CPR), which are essential for achieving sustainable outcomes in urban development.

The SSCF highlights the critical role of public participation in the urban planning process. It provides both conceptual and practical guidance on smart sustainable cities and establishes clear standards for public participation in city development, addressing potential debates on the framework’s implementation. This goes deeper into insights provided by actor involvement and ensures that the public plays a big role in enhancing urban areas [

25].

While smart city technologies may present risks to ethical standards and public trust, these can be mitigated through robust governance, clear data privacy protections, and public participation. Effective administration ensures that these tools enhance transparency and efficiency without compromising trust [

36].

2.1.2. Institutional Changes

Devolution of Authority and Inter-Ministerial Collaboration

The establishment of a balanced distribution of roles across different levels of government is essential for ensuring timely and high-quality service provision [

39]. Recent policy changes in Saudi Arabia have shifted toward decentralizing authority and enhancing collaboration between governmental ministries, particularly at the regional level. Decentralization efforts, as noted by the OECD [

5] and Bouregh [

27], have the potential to enhance local urban development by empowering local authorities and fostering more effective governance that is better suited to the unique needs of regional and community contexts. However, the success of these reforms depends on how effectively they are implemented, supported by clear governance structures, resource allocation, and stakeholder collaboration [

25].

The active participation of stakeholders in the planning process has shown that engaging stakeholders leads to more inclusive and widely accepted outcomes [

24,

27]. For example, urban planning projects that involve stakeholders produce more effective results. Another example of local cooperation among authorities is the structure of the Board of Regional Development Authorities, which includes representatives from local authorities across various ministries. This structure ensures regular meetings and coordination, replacing the previously sporadic ad hoc committees that were common before the establishment of the regional development authorities [

17].

Regional Development Authorities

The establishment of Regional Development Authorities (RDAs) in 2018 represents a step towards decentralized planning in Saudi Arabia [

17]. RDAs are intended to enable local regions to play a more active role in planning and development, thus fostering greater public participation in decision-making processes. By decentralizing authority, RDAs provide a platform for local people to participate directly in regional planning, linking national strategic goals with local needs and priorities [

40]. However, achieving a balance between these national goals and local aspirations remains a challenge, often leading to tensions between centralized governance and local participatory ambitions [

26]. Despite these challenges, opportunities to enhance public participation exist, such as improving communication channels between RDAs and local communities, utilizing digital platforms for broader participation, and creating participatory forums. These initiatives could help make city development more sustainable and efficient [

41,

42].

In Saudi Arabia, newly established RDAs manage all aspects of regional planning. They lead comprehensive planning and development across various sectors, including the economy, society, culture, environment, and infrastructure. They focus on providing public services and utilities efficiently while addressing multiple aspects of development simultaneously. New policies grant the RDAs expanded mandates for comprehensive regional planning, as well as the authority and funding necessary for implementation [

27].

RDAs formulate regional urban policies, produce strategic plans, and rehabilitate projects through partnerships with ministries and central agencies to address regional needs. They design and implement strategic programs, review development plans, administer infrastructure projects, monitor the performance of urban centers, and oversee land use controls as part of their legal mandate. Article 4 of the Organizing Regional and City Development Authorities (Cabinet Resolution No. 475, dated 22 May 2018) assigns RDAs the responsibility of comprehensively planning and developing the region in areas such as urbanization, population growth, economy, development, social and cultural affairs, environment, transportation, infrastructure, and digital infrastructure. They also work to meet the region’s needs for public services and facilities.

Table 2 outlines the specific functions carried out by RDAs, as established by this regulation.

2.1.3. Regulatory Change and Initiatives

Municipal Autonomy and Decentralized Decision-Making

In accordance with the Regions System issued by Royal Decree No. (92/1) dated 1 March 1992, Saudi Arabia divides the country into 13 regions (Emirates), each governed by a governor (Emir) appointed by the King. These regions are further subdivided into 138 governorates (Muhafazat), which manage local administration and regional planning. In turn, the governorates are divided into approximately 1349 administrative centers (Marakiz), responsible for rural areas and smaller settlements [

43,

44,

45,

46]. At the local level, around 285 municipalities are responsible for urban planning, public services, and local development, ensuring governance and services reach all communities [

40].

Saudi cities are advocating for greater devolution of planning powers to promote decentralized planning and decision-making, marking a shift from the previously centralized control by MoMRA [

7,

35]. This shift has granted municipalities more autonomy in developing their own plans [

47]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, there are currently 285 municipalities in Saudi Arabia, organized by size and function. These municipalities are classified into six categories: ‘Regional’, ‘Category A’, ‘Category B’, ‘Category C’, ‘Category D’, and ‘Category E.’ For instance, there are 17 municipalities in the ‘Regional’ category, 127 in ‘Category E’, 60 in ‘Category D’, 51 in ‘Category C’, 25 in ‘Category B’, and 5 in ‘Category A’ [

40]. Municipalities in Category A possess the highest level of authority, granting them greater decision-making power and autonomy in shaping urban development strategies, particularly in larger urban centers. This classification reflects varying degrees of decentralization and administrative capacity, with Category E municipalities having the least autonomy.

In 2019, MoMRA made a key decision to authorize and empower municipalities across regions, governorates, and various ministry officials to exercise their authority within the boundaries of established rules and instructions, furthering the goal of decentralizing decision-making. This ruling grants municipalities increased autonomy to perform their duties with greater efficiency and effectiveness, promoting more localized governance [

40].

Citing three different planning systems—Razin [

48], Hutchcroft [

49], and Eshel and Hananel [

50]—successful governance requires a balance between centralized and decentralized decision-making. Razin [

48] introduces the polycentric urban governance model, which emphasizes a shared power structure where local and national governments collaborate in decision-making. Hutchcroft [

49] presents the bureaucratic polity model, which, while traditionally centralized, has incorporated efforts to devolve power to local authorities. Erk and Koning [

51], Eshel and Hananel [

52] and Hutchcroft [

49] discuss local governance reforms, highlighting how decentralization allows local municipalities greater influence in urban and regional planning decisions.

This discussion is particularly relevant to contemporary Saudi Arabia, where, in a trend toward decentralization, power is gradually being shifted to local municipalities on a take-up basis in urban planning matters. According to Alkadry [

53], this strategic shift in municipal decentralization empowers local municipalities by positioning them at the forefront of shaping urban spaces in a participatory manner that is sensitive to local contexts and needs. Recent reforms have distributed more decision-making power to municipalities, allowing for better adaptation of planning processes to meet local needs.

The national, regional, and local levels intersect at the crossroads between the national government and municipalities, while MoMRA defines the national, regional, and local boundaries. Overall policy and regulation fall under MoMRA’s jurisdiction, as illustrated in

Figure 2. At the regional level, regional municipalities represent administrative bodies that implement policies issued by the central government, tailored to regional specifics. At the local level, municipalities, classified into five categories, remain the primary actors in local governance. These local bodies are responsible for the day-to-day administration and governance of their respective urban areas.

Furthermore, regional development authorities and municipalities operate across the national, regional, and local levels. They are intended to harmonize various initiatives and ensure that development aligns with broader strategic goals. The Development Authorities Support Centre (DASC), which is tasked with supporting and pooling resources for the regional development authorities, provides coordination and financial resources to these authorities. Together, regional development authorities and municipalities form a comprehensive governance framework, operationalizing the nation’s urban development strategies with clearly defined roles at the national, regional, and local levels. According to the Bureau of Experts at the Council of Ministers [

17] and the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs [50, 51], this approach ensures effective urban planning and implementation that is responsive to local and regional needs.

Urban Governance and Participatory Planning Approaches

In Saudi Arabia, urban governance has increasingly shifted toward decentralization, with local municipalities and regional development authorities gaining more decision-making power. This contrasts with the previous situation, in which decision-making was heavily centralized, with most authority concentrated at the national level, limiting local autonomy and the ability of municipalities to address region-specific issues effectively. This movement reflects a broader national effort to establish a more inclusive and participatory urban planning system, aligning with the objectives of Vision 2030 [

7]. At the same time, this transition reflects broader governance dynamics, where centralized control is progressively giving way to more localized decision-making, aligning with global trends that emphasize the balance between top-down and bottom-up planning approaches in urban governance [

37]

According to Alkadry [

53] and Alamoudi [

38], empowering municipalities is essential because their proximity to local populations enables them to better understand and address community-specific needs. Decentralizing authority ensures that decisions are made by officials with a deeper awareness of the social, economic, and environmental issues within their areas. This proximity fosters easier access to local authorities for the public, which enhances public participation and enables a more responsive and adaptive urban governance structure.

Public participation is a key component of this transformation, with workshops and consultations organized to involve a diverse range of stakeholders, including civil society organizations and local communities [

7,

54,

55,

56]. This participatory approach emphasizes the role of these groups in fostering dialogue between local stakeholders and government authorities, promoting transparency and inclusivity in urban planning [

19,

22,

57].

2.2. Summary of Literature Review and Policy and Document Analysis

The policy documents and the academic literature on the topic indicate that Saudi Arabia is shifting toward participatory urban planning under Vision 2030, moving from centralization to a more localized governance structure with a strong focus on public participation in regional development. This shift is achieved by encouraging activities that promote decentralization and empower municipalities and regional authorities to share power with the people and their leaders. Notable milestones include the establishment of regional development authorities for local planning in 2018 and the granting of greater autonomy to municipalities. The key recent changes are summarized in

Table 3.

3. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework serves to provide a structured lens through which the shifts in urban governance under Vision 2030 can be analyzed. It helps to explain how different political, social, and policy factors align to create opportunities for significant reforms, thereby supporting a deeper understanding of the dynamics involved in policy changes and public participation.

Kingdon’s “policy window” theory explains that opportunities for policy change occur when problems, policies, and politics align [

61]. In Saudi Arabia, Vision 2030 and its related reforms have created such an opportunity, especially for decentralization and public participation. However, the centralized governance system may limit the full potential of these participatory goals. Drawing on ideas from Kingdon and Fuhr [

38,

61], reform advocates must navigate this challenging political environment, where centralized control and socio-political factors, including people's rights issues, can restrict opportunities for public participation in urban planning.

Understanding this concept is central to explaining how and why certain issues rise to the political agenda and how policy change occurs. Kingdon’s policy window model specifies three streams—problems, politics, and policy—which help explain policy change. In the Saudi context, these streams are evident in the policy changes studied here. As shown in

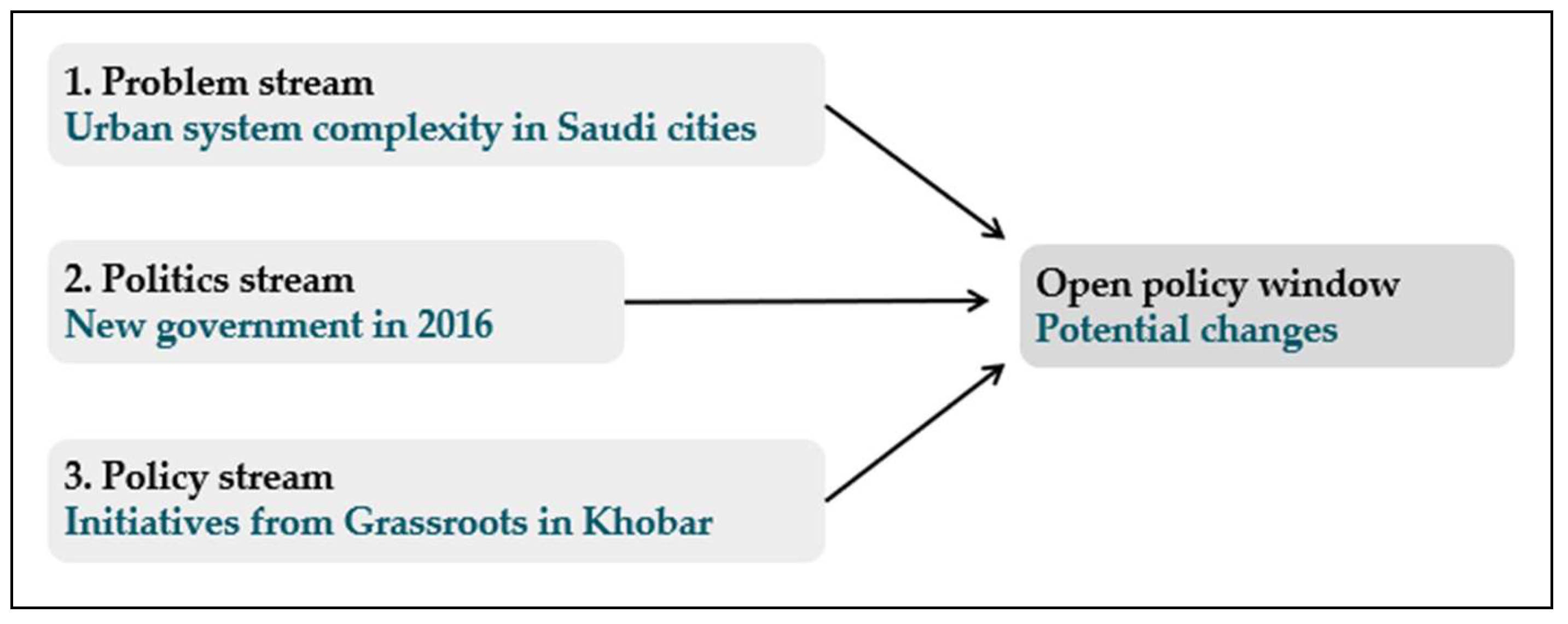

Figure 3, the problems stream relates to the complexity of the urban system, the politics stream corresponds to the arrival of the new government in 2016, and the policy stream reflects the participatory initiatives from grassroots movements in Saudi Arabia. Gaining more insight into the transformational shifts within Saudi urban planning highlights how these streams of problems, politics, and policy are directly connected to institutional and policy changes within the Saudi Arabian context.

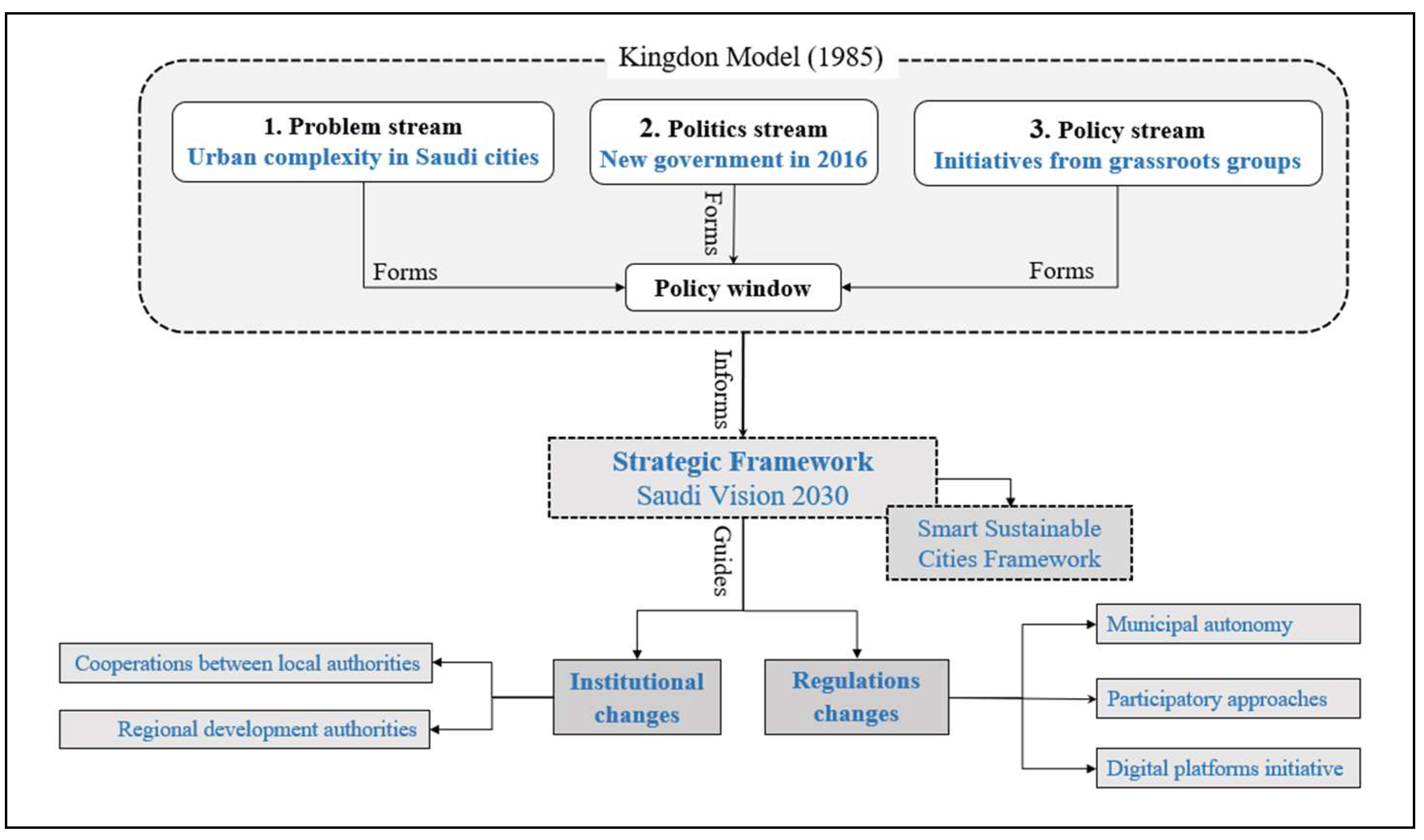

The Kingdon model, illustrated in

Figure 4, provides a framework for understanding the merging of problem streams, political streams, and policy streams in the context of Saudi Arabia’s urban planning. These elements work together to drive the country’s shift toward policy change. The alignment of these streams, particularly with decentralization policies and increased public participation, highlights the transformation from a ‘top-down’ policy approach to a more inclusive, participatory governance model aimed at addressing urban complexities and fostering policy changes in Saudi Arabia.

4. Materials and Methods

This study employs a multi-method approach to examine local participatory urban planning and its interaction with governance structures in Saudi Arabia. This paper is based on a literature review that explores scholarly debates and theoretical models. Following the approach highlighted by Xiao and Watson [

62] and Shaffril et al. [

63], it goes beyond summarization, offering critical analysis and synthesis of the related scholarly work to generate new conceptual understandings. Therefore, this paper draws on academic material to build an understanding of the complexities and dynamics of local participatory urban planning in Saudi Arabia by identifying various perspectives and gaps within the existing knowledge.

The literature review is complemented by an analysis of policies, urban planning documents, and reports. This part provides details on the key legal frameworks, comprehensive urban development plans, and important policy documents that guide the domain of urban planning and governance. Following Altheide's [

64] systematic approach, this paper selects the documents, arranges them systematically, and analyzes them to reveal patterns and meanings embedded therein. These patterns include recurring themes of decentralization, public participation, and the integration of technology in planning, while the meanings derived emphasize the growing focus on inclusivity and sustainability in urban governance. This critical review uncovers insights that contribute significantly to understanding local participatory urban planning, especially in terms of how new policies foster local empowerment and collaborative decision-making. This paper, therefore, provides a context in which theoretical findings from the reviewed literature are grounded in the practical and real-life frameworks guiding urban planning in the country. It thus seeks to bridge the gap between theory and practice in the realm of participatory urban planning.

In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a group of 20 experienced urban planners from Saudi Arabia, following the guidelines of Kallio et al. [

65], to gather information and offer perspectives on policy impacts and the practical aspects of local participatory urban planning. The decision to interview only urban planners was driven by their direct involvement in the implementation of recent policies and participatory urban planning initiatives. As key professionals in municipal authorities, regional development agencies, and private consultancy firms, urban planners possess direct knowledge of how governance reforms under Vision 2030 have influenced participatory mechanisms. Their expertise allows for an in-depth analysis of the practical challenges and opportunities in local urban planning. Additionally, selecting urban planners ensured that this study remained focused on policy implementation rather than broader public perception, which was addressed separately through the survey. Of the participants, 11 were academic experts who also worked in regional development authorities and municipalities, while 9 were urban planners employed solely in regional development authorities, municipalities, or private urban planning consultancies (

Table 4).

The interview guide, finalized prior to data collection, included questions focused on the respondents' experiences in these roles to ensure relevance. These questions addressed topics such as the influence of recent policies on local public participation and the methods used by urban planners in formulating urban plans.

The questions focused on the effects of recent policy changes, including territorial policies, the establishment of local development authorities, and Vision 2030-driven empowerment policies. These inquiries were designed to explore how these changes highlight the significance of responsive governance in participatory planning. The final sections of the interview guide addressed performance in relation to Vision 2030 objectives, challenges arising from the transition to more localized planning, and observations on the integration of public participation into urban development projects. Additionally, the guide examined perceptions of the balance between central government-led mega projects and local participatory projects, concluding with visions for local participatory urban planning in Saudi Arabia from the perspectives of the urban planners.

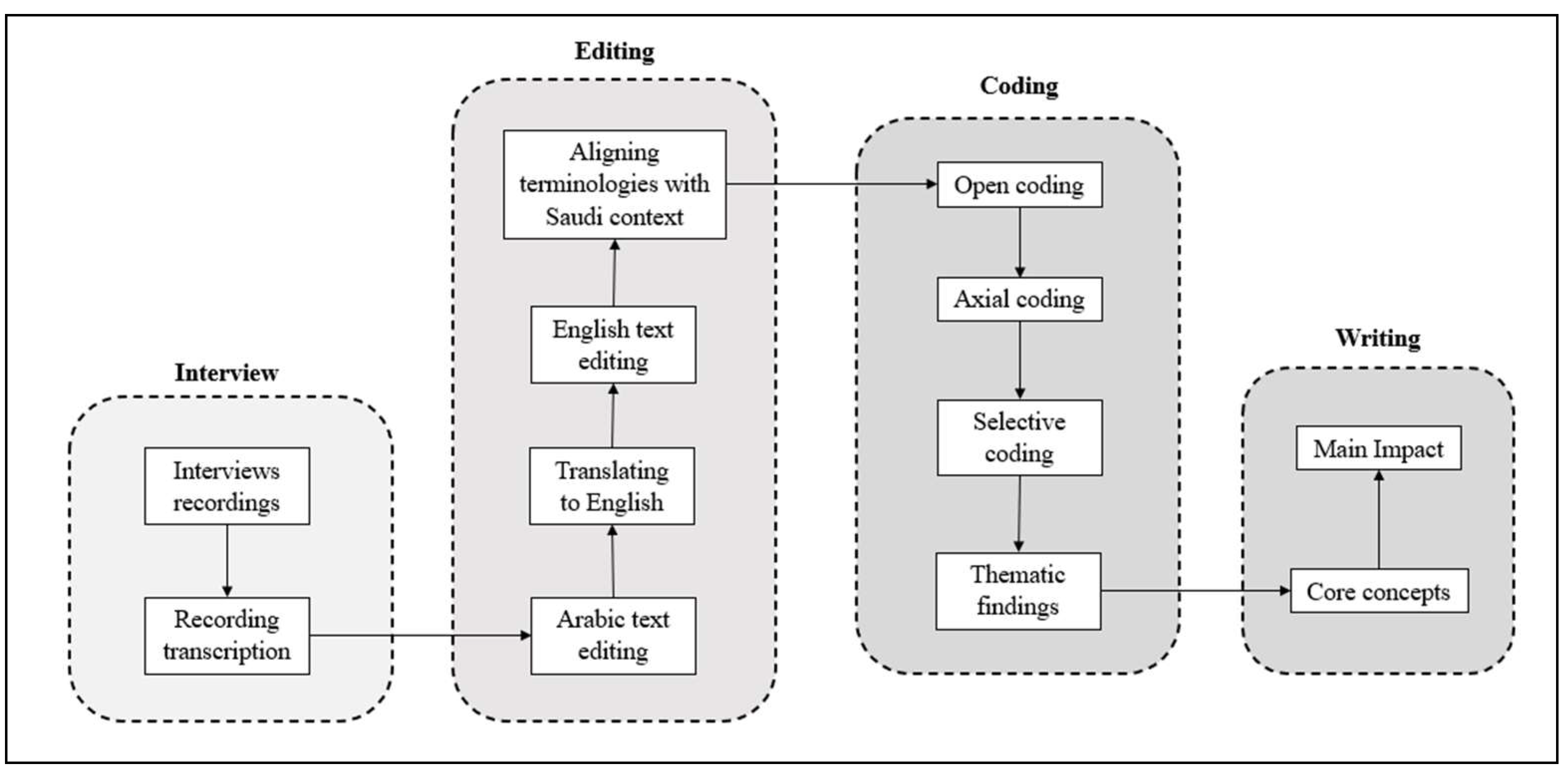

As shown in

Figure 5, the interviews were carried out using a systematic process that involved implementation, analysis, and summarization. During the interviews, recordings were made, and transcriptions were automatically generated. Once the transcripts were stored, the editing process began with Arabic text editing. The text was then translated into English, and content editing was conducted to ensure that all terminologies aligned with the context of Saudi Arabia. This stage included open coding, followed by axial coding, and finally selective coding using ATLAS.ti9 (Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software, CAQDAS), following the guidelines outlined by Friese [

50]. This process led to the identification of thematic findings. The final stage of writing involved expressing the core ideas developed through the coding process, culminating in an explanation of the main research impact.

The interviews aimed to gather insights into the impact of policies introduced from 2016 onwards on local participatory urban planning. The urban planners provided valuable perspectives on the current trends, potentials, and challenges within Saudi Arabian urban planning, drawing from their extensive experience and expertise in the field. Their insights contributed significantly to understanding how local participatory urban planning processes are evolving to foster sustainable, equitable, and well-organized urban spaces, cities, and communities across Saudi Arabia.

This paper employed employed a mixed-mode survey (online and in-person), alongside literature reviews, official reports, policy documents, and other sources as part of its data collection approach. The survey aimed to assess public perception regarding the impact of recent policies on local participatory urban planning. A total of 453 participants—144 in person and 309 online—provided input, representing a diverse mix of in-person and online experiences. Participants were selected using a combination of convenience sampling [

66] and stratified sampling [

67]. Convenience sampling was used to efficiently reach available participants across various locations, while stratified sampling ensured representation from multiple social settings, capturing a broader demographic cross-section.

The online survey was distributed via researchers’ personal and institutional networks, as well as social media platforms such as Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter (X), and WhatsApp groups. Meanwhile, in-person surveys were conducted by trained research assistants in Khobar’s parks, malls, sports centers, local festivals, and social events. Research assistants were specifically trained to approach individuals in a diverse manner, ensuring that the sample reflected a broad demographic representation.

5. Results from Interviews: Revealing the Impact of Recent Policies on the Transformation of Local Participatory Urban Planning

5.1. Strategic Shifts in Urban Planning and Decentralization

A significant finding from the interviews is the strategic shift from centralized to decentralized urban planning approaches, a key aspect of Vision 2030. This transition aligns with Kingdon’s policy window theory, as the convergence of the problem stream (urban complexity), the politics stream (government reforms since 2016), and the policy stream (participatory initiatives) has created an opportunity for reform. Decentralization aims to empower local governance, foster stakeholder collaboration, and enhance inclusiveness, sustainability, and efficiency in urban planning.

As one senior urban planner noted, “The establishment of regional development authorities has been a positive step in fostering participatory mechanisms” (I 7). This reflects the institutional shifts within the policy stream, where new governance structures facilitate greater involvement of local actors. However, as Kingdon’s model suggests, the effectiveness of these reforms depends on overcoming centralized control and socio-political constraints. The findings indicate that while Vision 2030 has opened a window for decentralization, its full realization requires addressing political and institutional challenges that may still limit public participation.

Decentralization has empowered municipalities to implement localized strategies, creating opportunities for public participation. Initiatives such as Istitlaa and Balady have provided platforms for public participation. However, challenges remain, including the need for clearer guidelines and sustainable frameworks. As one respondent remarked, “Decentralization is important, but it must be accompanied by effective coordination among municipalities to ensure meaningful participation” (I 12). This shift reflects global trends in decentralization observed in regions like Latin America and Southeast Asia, where reforms aim to strengthen local governance and public participation (I 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 14, 17, 20).

5.2. Stakeholder Collaboration and Public Participation

Enhanced collaboration between stakeholders—local authorities, private sector actors, and community members—has been another key outcome of recent policies. Participatory workshops and consultations have enabled communities to voice their concerns and contribute to urban planning decisions. For example, municipalities in larger cities have successfully organized these engagements to integrate public feedback. As one urban planner noted, “multi-stakeholder dialogues are improving the quality of public participation” (I 5).

Digital platforms have accelerated participation in urban areas, allowing municipalities to gather feedback efficiently. A digital planning specialist remarked, “The use of digital platforms has significantly sped up the process of engaging local communities” (I 8). However, rural areas face challenges such as limited internet access and technological literacy, hindering the inclusivity of these tools. As one respondent observed, “Digital platforms often exclude tech-illiterate populations and may result in fake or low-quality participation” (I 13).

5.3. Urban–Rural Disparities in Participation

The interviews highlight significant differences in participation levels between urban and rural areas. Urban planners in Riyadh expressed optimism about Vision 2030, citing examples where community feedback influenced urban projects (I 1, 8, 10, 12, 17, 18). In contrast, officials in smaller municipalities voiced frustration over resource limitations and the slow pace of reform (I 4, 7, 14, 17, 20).

While urban regions increasingly adopt digital engagement strategies, rural communities rely on traditional town hall meetings, which are often ineffective. “The voices of marginalized communities are often overridden in favor of top-down development agendas,” noted one lecturer in urban planning (I 4). This urban–rural divide underscores the need to tailor participatory mechanisms to local contexts to ensure inclusivity (I 1, 2, 3, 7, 10, 13, 14, 19, 20).

5.4. Resource Gaps and Institutional Capacity

Resource disparities between municipalities emerged as a recurring theme. Urban planners in smaller towns highlighted the lack of resources and institutional capacity as barriers to implementing participatory changes (I 2, 4, 6, 11, 16, 17). In contrast, larger cities benefit from better funding and institutional support, enabling more active community participation. As one urban planner noted, “Larger cities are equipped to adopt participatory tools effectively, but smaller towns are left struggling” (I 14).

Senior urban planners praised decentralization reforms for enabling faster decision-making processes (I 1, 5, 8, 13, 15, 16). However, policy critics argued that real power remains centralized, leaving local institutions under-resourced. “These reforms are often symbolic rather than substantive, leaving local institutions unable to operationalize participatory planning,” commented one critic (I 6).

5.5. Visionary Impacts and Sustainability

Recent policies have emphasized sustainability, quality-of-life programs, and environmental considerations as part of a visionary strategic framework. Long-term sustainability plans, climate action strategies, and resilience-building measures have been integrated into urban planning practices (I 1, 8, 10, 12, 17, 18). “The focus on sustainability is a significant step forward, aligning urban planning with global environmental goals,” remarked one urban planner (I 8).

Local participatory planning is essential to achieving these goals, particularly as policies prioritize environmental and quality-of-life factors. However, urban planners noted that effective implementation requires consistent public engagement and local support (I 1, 5, 6, 8, 11, 13, 15, 17).

5.6. Challenges and Ethical Concerns

Despite progress, significant challenges remain. Bureaucratic barriers, regulatory complexities, and limited transparency hinder participatory urban planning. Financial constraints further exacerbate these issues, particularly for smaller municipalities (I 3, 5, 8, 11, 16). Broader concerns include ethical and political implications, such as forced displacement and restricted public input in large-scale projects. “Centralized approaches in mega projects often sideline local voices, undermining the essence of participatory planning,” noted one respondent (I 4).

While Vision 2030 and the Smart Sustainable Cities Framework aim to modernize governance and enhance participation, their implementation has faced criticism. These challenges highlight the need for targeted policies to address regional inequalities and ensure meaningful participation for all communities (I 1–6, 8, 11, 12, 16–19).

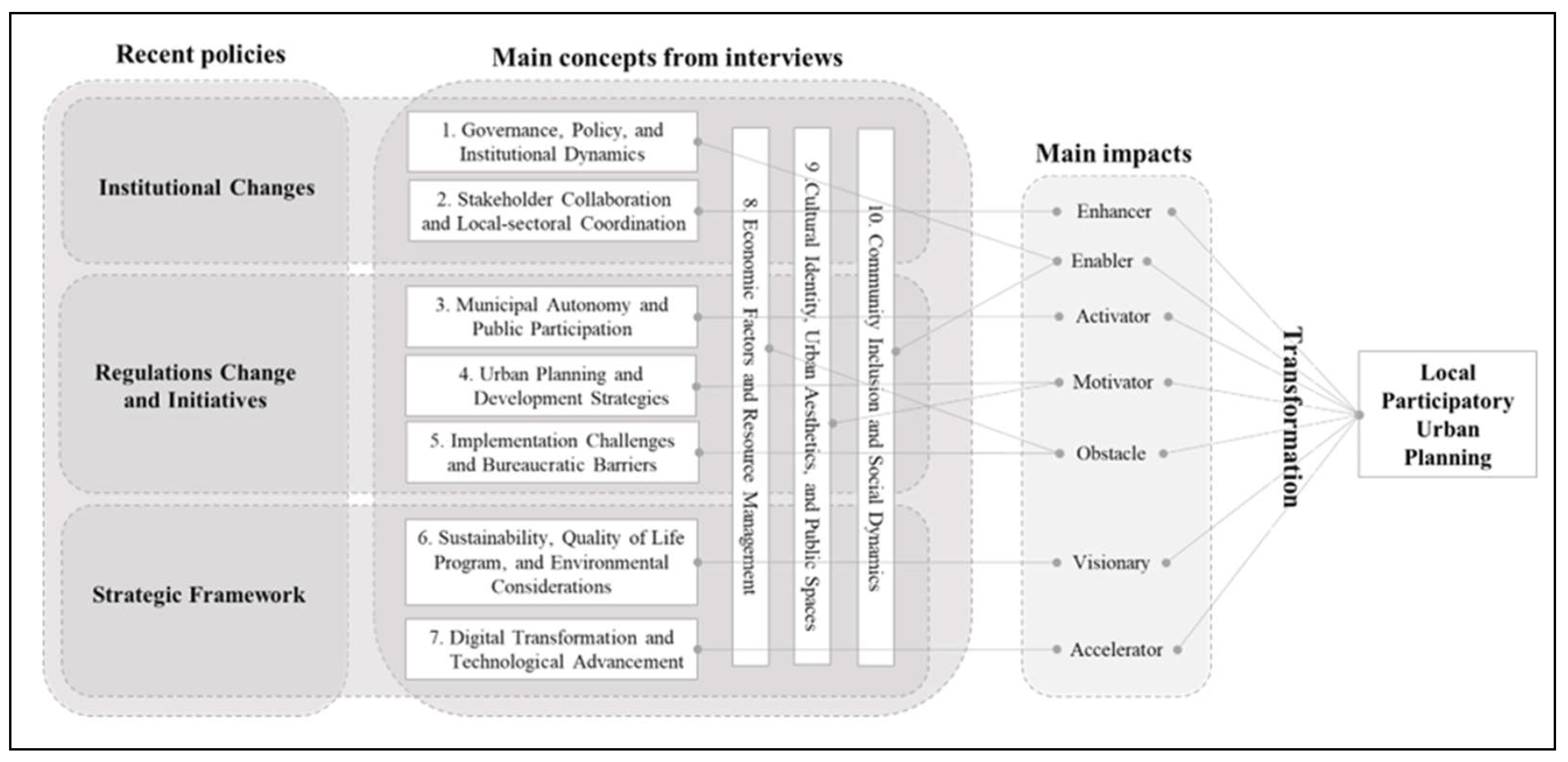

A summary of the key findings from the interviews is in

Table 5 and

Figure 6.

The following

Table 6 provides a summary of key nuances observed during the interviews.

6. Survey Results: Impact of Recent Policies on Local Participatory Urban Planning

The function of the survey in the methodology is to empirically assess whether recent policies introduced under Vision 2030 have effectively increased public participation in urban planning in Saudi Arabia. By collecting responses from 435 participants, the survey provides quantitative evidence regarding public perceptions of these policy changes. The results help to evaluate the real-world impact of these initiatives, highlight the variability of public opinion, and identify areas where policies may not have been fully effective or evenly implemented. This data-driven approach adds depth to the theoretical arguments by grounding them in the lived experiences and opinions of the affected population, thereby contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the effects of Vision 2030 on local participatory governance.

The survey, conducted by the author, examined whether Vision 2030 regulations introduced after 2016 have increased public participation in urban planning.

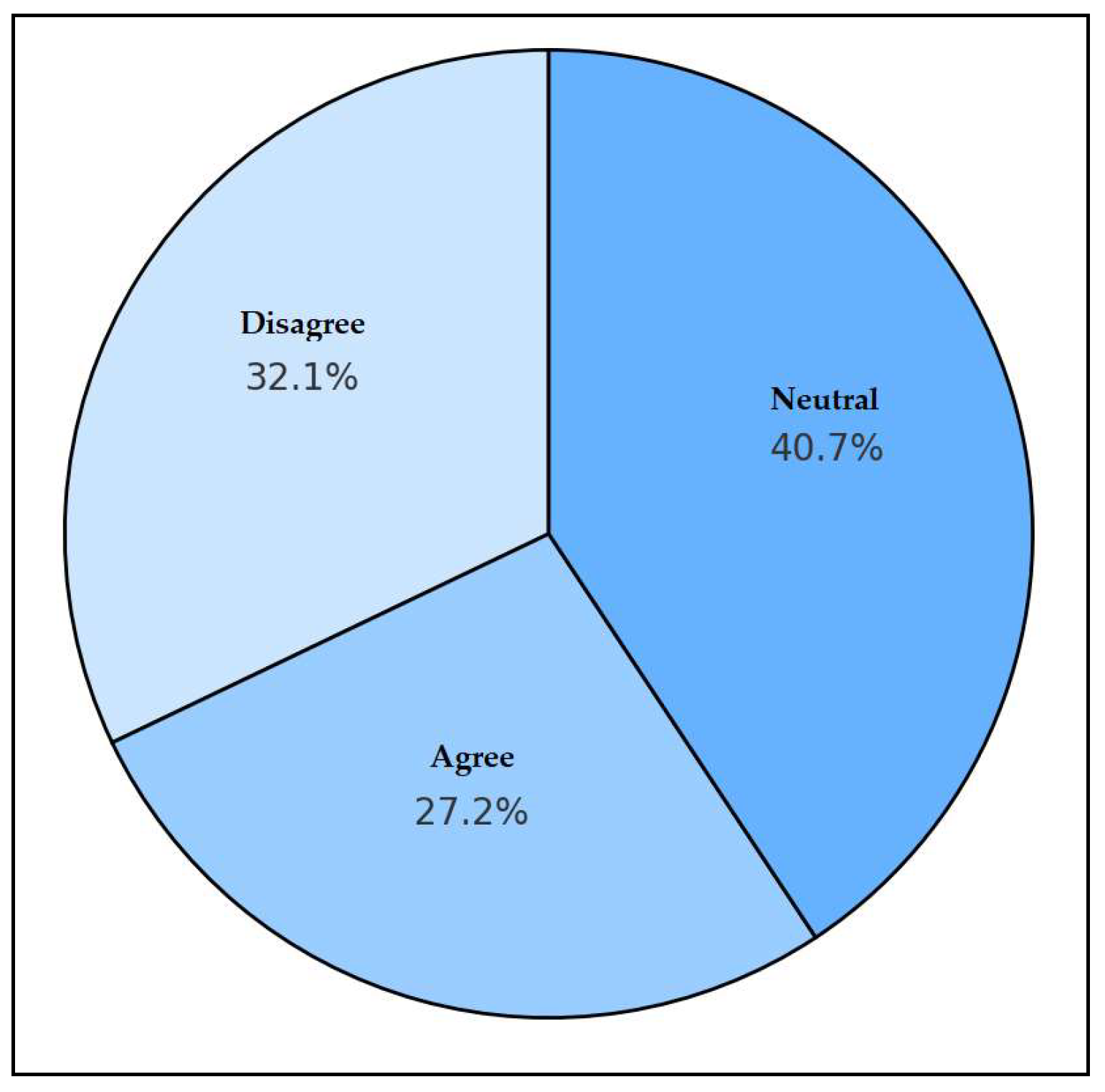

Figure 7 presents the survey introduction, guidance, and two sample questions, illustrating this paper’s purpose and the types of inquiries posed to participants. Among 435 respondents (

Figure 8), 40.7% were neutral, 27.2% agreed, and 32.1% disagreed. The mean score was 2.92 (close to neutral), indicating mixed views. The high level of neutrality may reflect limited awareness or uneven implementation across regions.

Further findings reveal significant participation barriers, as 76.04% of respondents had never participated in urban planning activities, reinforcing concerns about limited public involvement. However, 24% had participated at least once, suggesting the potential for increased actual participation if participation mechanisms are enhanced.

These mixed results indicate progress but also highlight areas for improvement. To make participation more impactful, policies should focus on increasing accessibility to participatory platforms, especially in less-engaged regions, and ensure that public input has a tangible influence on planning decisions. Tailoring approaches to local contexts and demonstrating how public feedback shapes outcomes could strengthen trust and encourage broader engagement, aligning with Vision 2030’s goals for inclusive urban development. This finding from the survey question moderately aligns with interview insights, which suggest that recent policies show promise but are hindered by bureaucratic and regulatory challenges that limit the depth of public participation.

7. Discussion

While interviews highlight progress in fostering local participatory urban planning, broader political and social challenges persist. Bureaucratic barriers, regulatory complexity, and displacement continue to hinder public participation within a centralized governance system [

7,

26]. These challenges raise concerns about the effectiveness of Vision 2030’s participatory initiatives.

Survey findings reflect these barriers, with a majority (76.04%) of respondents reporting that they had never participated in urban planning activities, indicating significant obstacles to engagement. However, 24% had participated at least once, suggesting a potential for greater involvement if public participation mechanisms are strengthened.

Furthermore, research highlights how these barriers contribute to broader inequalities. George [

68] and Bouregh [

27] argue that smart city projects often exacerbate disparities and limit public autonomy, particularly for marginalized groups. Similarly, Moshashai, Leber, and Savage [

15], along with Thompson [

9,

10], emphasize that Vision 2030’s economic reforms frequently overlook social consequences, particularly in terms of ensuring genuine public participation and addressing displacement issues.

Table 7 provides a comparative analysis of Vision 2030’s objectives in local participatory urban planning alongside the challenges and concerns that have emerged.

This table illustrates the tension between the vision’s stated goals of empowerment, local public participation, and sustainability and the challenges posed by centralization and the exclusion of marginalized groups in practice.

7.1. Limitations

While the 20 interviews offer valuable insights, they have limitations. Urban planners’ perspectives may focus on the positives of decentralization and participatory planning while overlooking ethical concerns, such as displacement or restricted public input in large-scale projects. Additionally, the portrayal of governance reforms may be overly optimistic, neglecting critical realities reported in media about authoritarian governance. Furthermore, the interviews may not fully capture the experiences of marginalized groups, private sector actors, or civil society organizations. A future study, involving more diverse perspectives, is needed to assess public perception and the ethical implications of these reforms.

Furthermore, the scope of the interviews may not capture the in-depth experiences and perspectives of marginalized communities or other stakeholders, such as private sector players and local community leaders, who are directly impacted by these developments. The lack of broader, non-governmental perspectives, including civil society organizations, limits this study’s ability to fully assess public perception and the ethical implications of these reforms. More research involving a wider range of public and diverse sources of evidence is needed to address these gaps and ensure a more comprehensive analysis of Vision 2030 and smart City initiatives.

7.2. Implications

If decentralization and local participatory urban planning continue to evolve in Saudi Arabia, they will have significant implications for the future of urban development. This process has the potential to make urban environments more responsive to local needs and priorities, ultimately improving the effectiveness of urban planning.

To situate this within the framework of the Kingdon [

61] policy window model, the current shifts in Saudi urban planning can be understood through the alignment of the three streams: problems, politics, and policies. The decentralization efforts address complex urban challenges, while the arrival of the new government in 2016 opened a political window of opportunity, allowing for the introduction of participatory urban planning initiatives.

From the problem stream perspective, Saudi Arabia's urban system has faced challenges due to rapid development, centralization, and a lack of community engagement in decision-making. The politics stream was activated with the Vision 2030 initiative, which focuses on reforming governance structures and encouraging public participation. The policy stream is embodied by grassroots initiatives like 'Your Voice Is Heard' and the digital platform 'Baladi', which emphasize inclusive and responsive urban planning practices [

7,

28].

These policy changes can be categorized into three elements: strategic framework, institutional changes, and regulatory reforms. Drawing on Kaufman and Herman [

30], the strategic framework provides the guiding vision for urban development, shaping institutional adaptations [

31] and regulatory reforms [

32]. This multi-layered transformation signifies a shift toward greater inclusivity in urban governance.

The novelty of these findings lies in identifying how participatory initiatives, catalyzed by political shifts, are reshaping the urban landscape in Saudi Arabia. Practically, these developments suggest that decentralization, paired with local participation, can create urban environments that are better aligned with community needs. Furthermore, this case contributes to the broader research on public participation by demonstrating how local governance structures can be reformed within a highly centralized political system, offering a unique context for studying policy entrepreneurship and participatory governance.

7.3. Recommendations

Future research should engage a broader range of stakeholders, including community representatives, private sector actors, and civil society organizations, to provide a more inclusive perspective on participatory urban planning. Quantitative assessments should also measure the impact of decentralization on urban productivity, service delivery, and public satisfaction.

For governmental organizations, structured public participation mechanisms should be reinforced, ensuring platforms like Balady and Istitlaa effectively translate public input into policy action. Strengthening coordination between regional development authorities and municipalities is essential for aligning participatory planning with tangible outcomes.

For non-governmental organizations, a greater role in public awareness, training programs, and independent evaluations can enhance transparency and inclusivity, particularly for marginalized communities.

Continuous policy reviews are needed to refine empowerment strategies, ensuring participatory governance remains adaptive and effective in Saudi Arabia’s evolving urban landscape.

8. Conclusions

The findings from this paper suggest that Saudi Arabia is making a transition from centralized urban planning toward a more decentralized and participatory approach under Vision 2030. Key policies and initiatives driving this transition include the establishment of Regional Development Authorities (RDAs), increased municipal autonomy, and e-platforms such as 'Balady' and ‘Istitlaa’, which aim to enhance local participatory urban planning.

While institutional changes—such as the establishment of RDAs and enhanced municipal autonomy—highlight promising steps toward increasing local participation, the full realization of participatory governance faces significant challenges. Bureaucratic barriers, regulatory complexities, and the exclusion of some communities, continue to undermine efforts to foster inclusive urban planning. Addressing these structural and procedural challenges is essential for achieving the intended outcomes of decentralization and public participation under Vision 2030.

The qualitative findings from urban planners indicate that decentralization policies have empowered municipalities by providing greater autonomy, but they also reveal concerns about regulatory barriers and the continuation of centralized control over major planning decisions. While digital platforms like Balady and Istitlaa have expanded public access to planning processes, some communities still face difficulties in fully participating. Interviews highlighted that participatory mechanisms are often symbolic rather than substantive, limiting the real influence of public input on decision-making.

The survey results reinforce these concerns. While 27.2% of respondents agreed that public participation has improved under Vision 2030, a substantial 40.7% remained neutral, and 32.1% disagreed, suggesting that the effectiveness of these policies is perceived as mixed. Additionally, 76.04% of respondents reported never participating in urban planning activities, confirming the persistence of participation barriers despite the introduction of participatory initiatives.

These findings indicate that while recent policies have laid a foundation for participatory urban planning, their actual impact on transforming public participation remains limited by bureaucratic hurdles, unequal implementation across regions, and centralized control over major decisions. Vision 2030’s stated goals of fostering inclusive, community-driven urban planning have yet to be fully realized. Moving forward, ensuring transparent decision-making, equitable access to participatory tools, and more meaningful public involvement will be crucial in overcoming these obstacles. Future research should explore ways to strengthen public participation mechanisms, address digital disparities, and enhance the role of local authorities in translating participatory policies into tangible urban planning outcomes.

Using John W. Kingdon’s policy window model, this study underscores the importance of aligning the streams of problems, policies, and politics for meaningful change. In the Saudi context, Vision 2030 acts as a catalyst where these streams converge: the problem stream involves urban development challenges, the politics stream includes governmental reforms and leadership changes, and the policy stream encompasses new participatory initiatives aimed at decentralizing governance.

In the Saudi context, improving institutional responsiveness and adaptability, especially in urban systems management for large populations, could open new opportunities for advancing participatory urban planning. For Vision 2030 to meet its transformative potential, a balanced approach that addresses both the aspirations of modernized, sustainable urban planning and the reality of the broader political context is essential. Continuous efforts in policy refinement must ensure that digital transformation and public participation initiatives extend their benefits to all groups, particularly some communities. Only through this balanced, inclusive approach can Vision 2030's objectives for participatory planning be fully realized, ultimately shaping a resilient, equitable urban future for Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions

F.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, project administration, visualization, funding acquisition, writing—original draft preparation, and writing; M.D., R.R., C.F.: review and editing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a scholarship from the Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia. The author acknowledges the financial support provided under the scholarship program of the Ministry of Culture. More information about the program can be found at

https://scholarship.moc.gov.sa/programs (accessed on 11 October 2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee TU Delft (3880, 3831, 3832 and 3 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. The consent form for this paper was developed by Fouad Alasiri from TU Delft. It invites 20 urban planners to participate in an interview lasting approximately 45 min, covering topics such as urban planning experiences post-2016 government reforms, policy impacts on participatory urban planning, and future challenges and tools in the field. The form emphasizes confidentiality, stating that personal data will be anonymized in any research outputs. It states that participation is voluntary, and the interview will be recorded for accuracy, with the option to withdraw at any time without providing a reason.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the privacy and confidentiality agreements with interview participants. Access to the data is restricted to ensure adherence to ethical guidelines related to the privacy of individuals and organizations involved in this study.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia, for their generous funding and support. We also thank the urban planners and local government officials who participated in the interviews and provided invaluable insights. Special thanks to our colleagues at Delft University of Technology for their continuous support and feedback. Finally, we acknowledge our families and friends for their patience and understanding throughout this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, J.L. The Public Participation Handbook: Making Better Decisions Through Citizen Involvement; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Planning in relational space and time: Responding to new urban realities. Plan. Theory Pract. 2001, 2, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E.; Booher, D.E. Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century. Plan. Theory Pract. 2004, 5, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Making Decentralisation Work: A Handbook for Policy-Makers; OECD Multi-Level Governance Studies. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/g2g9faa7-en.pdf?expires=1727716988&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=B46E3236D483D2282E49BB1A85FD97C4 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Rakodi, C. Politics and performance: The implications of emerging governance arrangements for urban management approaches and information systems. Habitat Int. 2003, 27, 523–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Saudi Cities Report; Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2019; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/05/saudi_city_report.english.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Chatham House. Vision 2030 and Saudi Arabia’s Social Contract: Austerity and Transformation. The Royal Institute of International Affairs. 2017. Available online: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2017-07-20-vision-2030-saudi-embargoed.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Thompson, M.C. The impact of vision 2030 on Saudi youth mindsets. Asian Aff. 2021, 52, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Saudi Cities Report; Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2018; Available online: https://saudiarabia.un.org/en/31245-saudi-cities-report-executive-summary (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosárová, D. Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030. In Security Forum 2020, the 13th Annual International Scientific Conference; Interpolis: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2020; pp. 124–134. ISBN 978-80-973394-3-2. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. NEOM: Futuristic Saudi City Leaves Some Locals Displaced and Divided. 2023. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-68945445 (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Shihabi, A. NEOM: Inside Saudi Arabia’s Plan for a Futuristic City—And the People Being Forced to Make Way. The Independent. 2023. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/neom-saudi-arabia-city-mbs-huwaitat-b809153.html (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Moshashai, D.; Leber, A.M.; Savage, J.D. Saudi Arabia plans for its economic future: Vision 2030, the National Transformation Plan and Saudi fiscal reform. Br. J. Middle East. Stud. 2018, 47, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Transformation Program. 2016. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/explore/programs (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Bureau of Experts at the Council of Ministers. Tantheem Haeyat Tatweer Almanatiq Walmodon [Organizing Regional and City Development Authorities]. 2018. Available online: https://laws.boe.gov.sa/BoeLaws/Laws/LawDetails/2ae2b616-e5c9-4b81-b55e-ae3d00acbf1a/1 (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Quality of Life Program. 2018. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/vision-2030/vrp/quality-of-life-program/ (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Thompson, M.C. ‘SAUDI VISION 2030’: A viable response to youth aspirations and concerns? Asian Aff. 2017, 48, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albassam, B.A. Achieving sustainable development by enhancing the quality of institutions in Saudi Arabia. Int. Sociol. 2021, 36, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Madina. Prince of Asir Sponsors a Workshop to Discuss 20 Recommendations for Protecting Ancient Trees in the Region. 2021. Available online: https://www.al-madina.com/article/714662 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Al-Ray News. Asir Development Authority Holds an Interactive Workshop “Formulating the Vision for the Development of the Asir Region” in the Heritage Village of Rijal Almaa. 2018. Available online: https://alraynews.net/6429310.htm (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Bin Taheetah, M. Asir Development Authority and Civil Aviation hold workshop for “Designing New Abha Airport”. Slaati News. 2020. Available online: https://slaati.com/2020/01/30/p1574276.html (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Aldegheishem, A. Community participation in urban planning process in Saudi Arabia: An empirical assessment. J. Urban Manag. 2023, 12, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshuwaikhat, H.M.; Adenle, Y.A.; Almuhaidib, T. A lifecycle-based smart sustainable city strategic framework for realizing smart and sustainability initiatives in Riyadh City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almughairy. Decentralization and development: The case of regional development authorities in Saudi Arabia. Middle East. Stud. Rev. 2019, 12, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouregh, A.S. A conceptual framework of public participation utilization for Sustainable Urban Planning in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Mobility Consulting. Revolutionizing Urban Living: Saudi Arabia’s Smart City Vision. 2023. Available online: https://saudimobilityconsulting.com/revolutionizing-urban-living-saudi-arabias-smart-city-vision/ (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Aldegheishem, A. Urban Growth Management in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: An Assessment of Technical Policy Instruments and Institutional Practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, R.; Herman, J. Strategic planning for a better society. Educ. Leadersh. 1991, 48, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, J.; Thelen, K. Explaining Institutional Change Ambiguity, Agency, and Power; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, F.R.; Jones, B.D. Agendas and Instability in American Politics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Doheim, R.M.; Farag, A.A.; Badawi, S. Smart city vision and practices across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A review. Smart Cities Issues Chall. 2019, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoMRA. Planning Evolution in Saudi Arabia; MoMRA: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Washington Institute. The Stalling Visions of the Gulf: The Case of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. 2024. Available online: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Mehmood, R.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Corchado, J.M. Smart technologies for sustainable urban and regional development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoMRA. National Reports. Habitat III. 2016. Available online: https://habitat3.org/documents-and-archive/preparatory-documents/national-reports/ (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Alamoudi, A.K.; Abidoye, R.B.; Lam, T.Y. Implementing Smart Sustainable Cities in Saudi Arabia: A Framework for Citizens’ Participation towards Saudi vision 2030. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhr, H. Institutional change and new incentive structures for development: Can decentralization and better local governance help? WeltTrends 1999, 25, 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- MoMRAH. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s Report on the Implementation of the New Urban Agenda. Ministry of Municipal, Rural Affairs & Housing. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2022. Available online: https://www.urbanagendaplatform.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/NUA%20Report%20Final_05Dec2022-compressed.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Alshaikh, A.B. Citizen participation in Saudi Arabia: A study of the ministry of labour. Asian Aff. 2019, 50, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czornik, K. Saudi Arabia as a regional power and an absolute monarchy undergoing reforms. vision 2030—The perspective of the end of the second decade of the 21st Century. Przegląd Strateg. 2020, 10, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Experts at the Council of Ministers. Law of Regions. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 1992. Available online: https://laws.boe.gov.sa/BoeLaws/Laws/LawDetails/93f81644-fbbc-49ca-b33c-a9a700f16701/1 (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- General Authority for Statistics. (n.d.). Statistical Atlas of Saudi Arabia. General Authority for Statistics, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/ar/page/170 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Ministry of Interior. Emirates and Governorates in Saudi Arabia; Ministry of Interior: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2024. Available online: https://www.moi.gov.sa/wps/portal/Home/emirates/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8ziLQPdnT08TIy83Q0dzQwcPc2N_A08TQ3dPY30wwkpiAJKG-AAjgZA_VFgJc7ujh4m5j4GBhY-7qYGno4eoUGWgcbGBo7GUAV4zCjIjTDIdFRUBAApuVo7/dz/d5/L2dJQSEvUUt3QS80TmxFL1o2XzBJNDRIMTQyS0dBREIwQUEzUTlLNUkxMEw0/ (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Saudi Geological Survey. Geological Study Report. 2012. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20190424125943/https://www.sgs.org.sa/Arabic/News/SGSNews/Documents/SGS_001.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Aina, Y.A.; Wafer, A.; Ahmed, F.; Alshuwaikhat, H.M. Top-down Sustainable Urban Development? urban governance transformation in Saudi Arabia. Cities 2019, 90, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razin, E. Checks and Balances in Centralized and Decentralized Planning Systems: Ontario, British Columbia and Israel. Plan. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchcroft, P.D. Centralization and decentralization in administration and politics: Assessing territorial dimensions of authority and power. Governance 2001, 14, 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, S. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.ti; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Erk, J.; Koning, E. New structuralism and institutional change: Federalism between centralization and decentralization. Comp. Political Stud. 2009, 43, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshel, S.; Hananel, R. Centralization, neoliberalism, and housing policy central–local government relations and residential development in Israel. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2019, 37, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkadry, M.G. Saudi Arabia and the Mirage of Decentralization. In Public Administration and Policy in the Middle East; Dawoody, A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazal, Z. Eastern Province Municipality Organizes a Participatory Workshop with Cyclists from Dammam and Qatif. Shafaq Electronic Newspaper, 2023. Available online: https://shafaq-e.sa/208282.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Al-Saudialyaum. Photos: Eastern Province Secretary Sponsors Workshop on Building Compliance Certification Application “11,854 buildings Targeted”. Al-Saudialyaum. 2024. Available online: https://alsaudialyaum.com/news/43748 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Bureau of Experts at the Council of Ministers. Netham Aljameat Alahliah [Civil Association Regulations]. 2015. Available online: https://laws.boe.gov.sa/BoeLaws/Laws/LawDetails/37e0768f-8e3c-493a-b951-a9a700f2bbb1/1 (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Planning and City Development Association. Involve All Stakeholders in the Decision-Making Process to Ensure Sustainable City Development [Tweet]. X. 2020. Available online: https://x.com/pcda_sa/sttus/1322883966093938690?s=46&t=1wzdjrdRjAps_XHaPPWnjg (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Balady. Balady Initiatives. Balady Platform. 2024. Available online: https://balady.gov.sa/en/initiatives (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Istitlaa. Istitlaa Platform for Public Consultations. National Competitiveness Center. 2024. Available online: https://istitlaa.ncc.gov.sa/ar/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Digital Government Authority. Saudi Vision 2030. Saudi National Portal. 2023. Available online: https://www.my.gov.sa/wps/portal/snp/content/saudivision/?lang=en (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- King, A. Review of Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, Boston, by J. W. Kingdon. J. Public Policy 1985, 5, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasiri, F.; Dąbrowski, M.; Rocco, R.; Forgaci, C. Survey on public perception of Vision 2030’s impact on urban planning participation. 2024; Unpublished dataset. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed Shaffril, H.A.; Samsuddin, S.F.; Abu Samah, A. The ABC of systematic literature review: The basic methodological guidance for beginners. Qual Quant 2021, 55, 1319–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altheide, D.L. Tracking discourse and qualitative document analysis. Agric. Hum. Values 2000, 17, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.W. Convenience Sampling Revisited: Embracing Its Limitations Through Thoughtful Study Design. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2021, 115, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Mangat, N.S. Stratified Sampling. In Elements of Survey Sampling; Kluwer Texts in the Mathematical Sciences; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; Volume 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R. The Rise of Gulf Smart Cities. Wilson Center. 2024. Available online: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/rise-gulf-smart-cities (accessed on 27 November 2024).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).