1. Introduction

We experience our surroundings through all our senses, incl. our sense of smell. In fact, our most durable memory of a place is often its smell [

1]. Despite this, in the context of the urban environment, smell is a much underexplored aspect of place experience. Research on the topic often deals with smell from the viewpoint of air quality and odor nuisance control [

2]. However, studying smell as a positive aspect of urban settings opens up an array of possibilities for using the benefits of natural smell and its connection to human experience and well-being [

3]. Smell can enrich sensory experiences, guide behavior, and offer an identity to a place by adding distinctive impressions linked and contributing to its socio-cultural characteristics [

2]. It is, for instance, a crucial factor in how people experience spaces of health and well-being, where activities that include smell can lead to greater engagement and participation [

4]. But the existing literature lacks knowledge on smell and its place-related meanings, as well as frameworks, methods, and policies to analyze, design, and manage smell [

3].

Urban Park smellscapes are dominated by odors from human activities and nature where the two parameters share a complementary relation [

5]. The smells in green spaces are thus largely connected to the plants the area consists of. Plant scent is an important factor in plant–environment interactions [

6]. It is a key parameter for the survival of plants and pollinating animals and is crucial for biodiversity and environmental sustainability [

7]. But it can also have great significance for human beings. Plant scents, with their high level of complexity [

8,

9], are some of the finest the world offers when it comes to smells. At the same time, they can affect us on a physiological and psychological level, both positively and negatively [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Managing plant scent in urban public green spaces, however, rarely captures the attention of the local authorities. If a city’s public green space is meant to support people’s living conditions and health smell-wise, there is a need to be able to work with plant scent in a targeted manner. However, as recognized by many researchers and practitioners, it is far from straightforward to work with scent. “Scent is the most potent and bewitching substance in the gardener’s repertory and yet it is the least understood” [

14] (p. 6).

This article takes up this challenge by suggesting a targeted approach to introducing plant scent in public green spaces. The suggested framework is particularly relevant for planners and landscape architects, but also for other built-environment professionals with an interest in improving public green spaces and urban biodiversity.

1.1. Plant Scent

Smells are small volatile molecules that are carried either in the air or on small water droplets from the smell source to the smell via inhaled air [

15]. It is the diverse structure of these molecules that cause them to be perceived as distinctive smells, and the slightest variation in composition and concentration can change the way you perceive a molecule’s smell completely [

16]. Humans can theoretically distinguish about 10,000 smells [

16]. Plant scents are generally complex, and a plant scent can consist of up to 300 different molecules [

7]. It is this complexity that makes us experience them as uniquely nuanced and deep. Rose is a good example of a multifaceted scent; it consists of between 40 and 100 different molecules [

8], whilst the scent varies according to the type of rose in question. Some roses smell fruity, others are musky or tea-like, and so on [

14].

Plant scent is stored as essential oils in the plant. These oils are often stored in special cells in the skins and surfaces of the plant, such as the flower, leaf, and root [

7]. Seeds and fruits can also contain essential oils—such as citrus fruits, where the oil is in the peel [

14]. In addition, they can be dissolved in resin in wood and bark [

17].

The essential oils in leaves, wood, and bark repel insects and animals with their pungent scent and taste. This prevents animal bites and insect attacks. In addition, essential oils can be antiseptic and protect the plant against diseases [

9]. In leaves, the oils are released either by rubbing or crushing the leaf—a light touch can also be enough, depending on how the oils are stored. In some cases, the scent is released from the surface of the leaf, and here no touch is necessary [

14]. As an example, rosemary releases its foliage scent into the air using heat. From wood and bark, resin is released by the pressure and damage caused by natural forces such as frost and wind [

18].

The scent from flowers is controlled by the plant’s life cycle and the circadian rhythms that are specific to each species. Light intensity, the day and night cycle, and temperature changes can promote or inhibit scent impulses depending on the plant species [

7]. The function of a flower’s scent, in conjunction with its shape, color, and texture, is to attract pollinators to ensure the maintenance of the plant species. A pollinator probably perceives a flower scent as messages that play a crucial role in its survival [

7]. The floral scent of different plant species is specifically adapted to attract one or more pollinating animals and, in addition to varying in their time of release, their scents can also be of very different characters [

14]. You could say that plant scent is the invisible coordinator of the animal kingdom, influencing animal behavior with an irresistible force [

8], which points to plant scent being a key factor in a thriving ecosystem.

1.2. The Significance of Plant Scent for Humans

Plant scent not only plays an important role in the ecosystem for plants and animals, enriching biodiversity, but it can also be significant for human beings in terms of their well-being and spatial experiences. With each inhalation, we are influenced consciously and unconsciously by smells from our surroundings on many levels [

19,

20]. For example, scent molecules can have a physiological effect on organisms. Animal experiments have shown that inhaling lavender causes a similar effect to the intake of diazepam, a substance found in sleeping pills [

13]. There is also research into so-called “forest bathing” or shinrin-yoku, which is an originally Japanese phenomenon that involves going out into the forest and improving one’s health by becoming fully immersed in the forest’s sensory environment. In connection with this, researchers have found that scents from conifers can have a directly vitalizing effect [

10,

11].

In general, smells can also, to a great extent, arouse an emotional response. Smells have a unique ability to evoke emotions and the memories associated with them [

15], which is related to the way olfactory information is processed in the brain. An example that is often highlighted when discussing smell is Marcel Proust’s description of a madeleine cake in the novel In Search of Lost Time, where the taste and smell send the main character directly back into a certain familiar feeling linked to a childhood memory, contributing to the emotional experience of eating the cake [

21]. The hedonic and arousing effects of smell are used quite purposefully in marketing where, for example, a hotel chain’s scent is designed intentionally to send out a pleasant message about the hotel’s environment and services [

22].

1.3. Existing Approaches to Designing with Smell in the City

Henshaw suggests a four-step process for “urban smellscape design” that can work at several scales, including at the city, neighborhood, and site level [

23]. The design process starts with an analysis of the smells on site and, over time, in conjunction with physical and spatial characteristics such as wind conditions, microclimates, the density of activity, surface materials, and topography, which have an influence on the smell sources and dispersion in an area. Afterwards, it is about clarifying the purpose in relation to the smells analyzed onsite. Basic design and management principles can be used to deal with the wanted and unwanted smells, including separating smells based on activities; removing unwanted smells or masking them; or introducing new smells to give the place a special character. The third step includes designing and implementing the scheme considering the site’s characteristics and the possible effects of smells, such as the ‘wake effect’ and ‘flooding effect’. The final step concerns the operation of the implemented scheme and evaluating it against the design objectives to collect city-wide feedback as a future design reference on what effects smellscapes will result in [

23].

Nevertheless, it is important to remember that smellscapes are only one of many sensory aspects of a place. This is catered for in a tool developed by Lucas and Romice that allows for the examination of tactile, visual, kinetic, thermal, auditory, and chemical stimuli by looking at their strength in relation to each other, as well as temporal aspects such as whether they are constant, repetitive, or changing [

24]. Henshaw used this method in her smell exploration of Doncaster and found it useful to capture simple real-time sensescape information and the role of smell within it whilst not capturing the complexity of olfactory perceptions and differences [

23]. When focusing exclusively on smell, the smellwalk method, either participatory or phenomenological, can provide rich information on the smell environment and its perception. In a smellwalk, the perceived smells and olfactory experiences are recorded at selected points along a route and analyzed in terms of their intensity, duration, and environmental characteristics [

25]. In addition, Bull suggests evaluating the acceptance of a smell in a specific context; one can look at the frequency of its detection and its intensity, duration, localization, and offensiveness [

26].

1.4. Existing Approaches to Designing with Plant Scent in the City

Looking at the role of fragrant plants and waterscapes in creating urban smellscapes, Xiao et al. suggest four areas of focus: select appropriate plant types from the local area; design at a human scale and within a detectable distance; design with activities that could activate smells in the environment; and consider seasonal changes and environmental sustainability [

27]. These areas of advice point to the great potential in working more purposefully with fragrant plants so that their scent can enrich the creation of unique urban identities and form “smellmarks” in the city. One example is the smell of bitter oranges in Athens mentioned by Xiao et al. [

27].

Although the studies reviewed are useful for providing a theoretical basis for urban practices that consider smell, there is limited guidance and practical knowledge, particularly on how to apply these design and management principles to develop design briefs and schemes. Thus, this article aims to examine these theoretical design principles through practice to advise others on how to work purposefully with plant scent to create urban public green spaces as part of a multisensory design framework.

2. Materials and Methods: Exploring the Use of Plant Scent in Two Landscape Design Projects

Learning from the tacit knowledge [

28] gained in practice by landscape designers who have purposefully used plant scents in their projects will offer the grounds for examining this theoretical knowledge and offer insights into the future practice of embedding plant scents. Two projects were selected to gain an in-depth understanding of the use of plant scent in therapeutic landscape design projects in an urban context, with access to the design team and the site provided: The therapeutic garden at the Danner Crisis Shelter in Copenhagen, Denmark, called Danner’s Garden, and the sensory garden at the Midlands Art Centre (MAC) in Birmingham, the UK.

The selection of these cases was information-oriented “to maximize the utility of information from small samples” and the two cases were chosen “on the basis of expectations about their information content” [

29] (p. 230). Moreover, the interviewees were selected for their ability to provide qualitatively rich and detailed information on the topic.

The interviewee connected to Danner’s Garden is a landscape architect and researcher who took part in the evidence-based design [

30,

31] of the garden, including its original design, post-occupancy evaluation, and the improvement of the design according to the results. Her knowledge on the use of plant scent in the garden stems from this process. The evaluation of the garden design consisted of landscape analyses, the observation of physical traces, and interviews with staff and residents. The subsequent improvement of the design happened through a participatory design process with staff [

32].

The interviewee connected to the sensory garden at the MAC was the lead landscape designer behind the project, with knowledge on both the users’ wishes for the garden and post-occupancy feedback that stems from conversations with staff before and after the garden was built. The design process also included fruitful collaboration with a gardener.

A drawing interview (see

Figure 1) with semi-structured questions was used to facilitate conversation with the interviewees from the selected projects. Drawing is a day-to-day communication method for landscape designers. The integration of drawing into the interview process enabled the participants to feel more comfortable with the interview and express their thoughts more freely. Drawing and visual content also work as stimuli to help interviewees recall memories of designing the project and organize their thoughts when answering the questions [

33]. To obtain in-depth information on the use of plant scent in the projects, the questions were centered around the smell objectives, selection of plants, spatial organization, and post-occupancy reflections and are listed as follows:

Could you please talk through the design of the park/garden? (Please draw where possible.)

Was the sense of smell considered in the design? If yes, what was the purpose? How do people interact with it? (Please draw where possible.)

Did you get any feedback from the users on the smells?

If you were to redesign it, would you consider re-introducing smells into the design? How? Any examples? (Please draw where possible.)

Any other thoughts on considering plant scents in urban green spaces?

3. Results: An Applied Framework to Design with Plant Scent

The above sections list several approaches to design, including evidence-based design [

30,

31], Henshaw’s four-step process for urban smellscape design [

23], and Xiao et al.’s advice for designing with fragrant plants and waterscapes in the urban space [

27]. While evidence-based design is an overall process that includes the use of best evidence in making decisions about the design, Henshaw depicts a similar process but with a focus on smellscapes in the urban environment. Moreover, Xiao’s advice specifically deals with smellscapes based on plants and water features. Based on these approaches, the framework presented in the following section goes into detail on the connections between the nature of plant scent, human access to scents through design, and the perception and effect of scent. The framework is thus meant to be understood and used as a part of an overall approach to the process of completing a given design project.

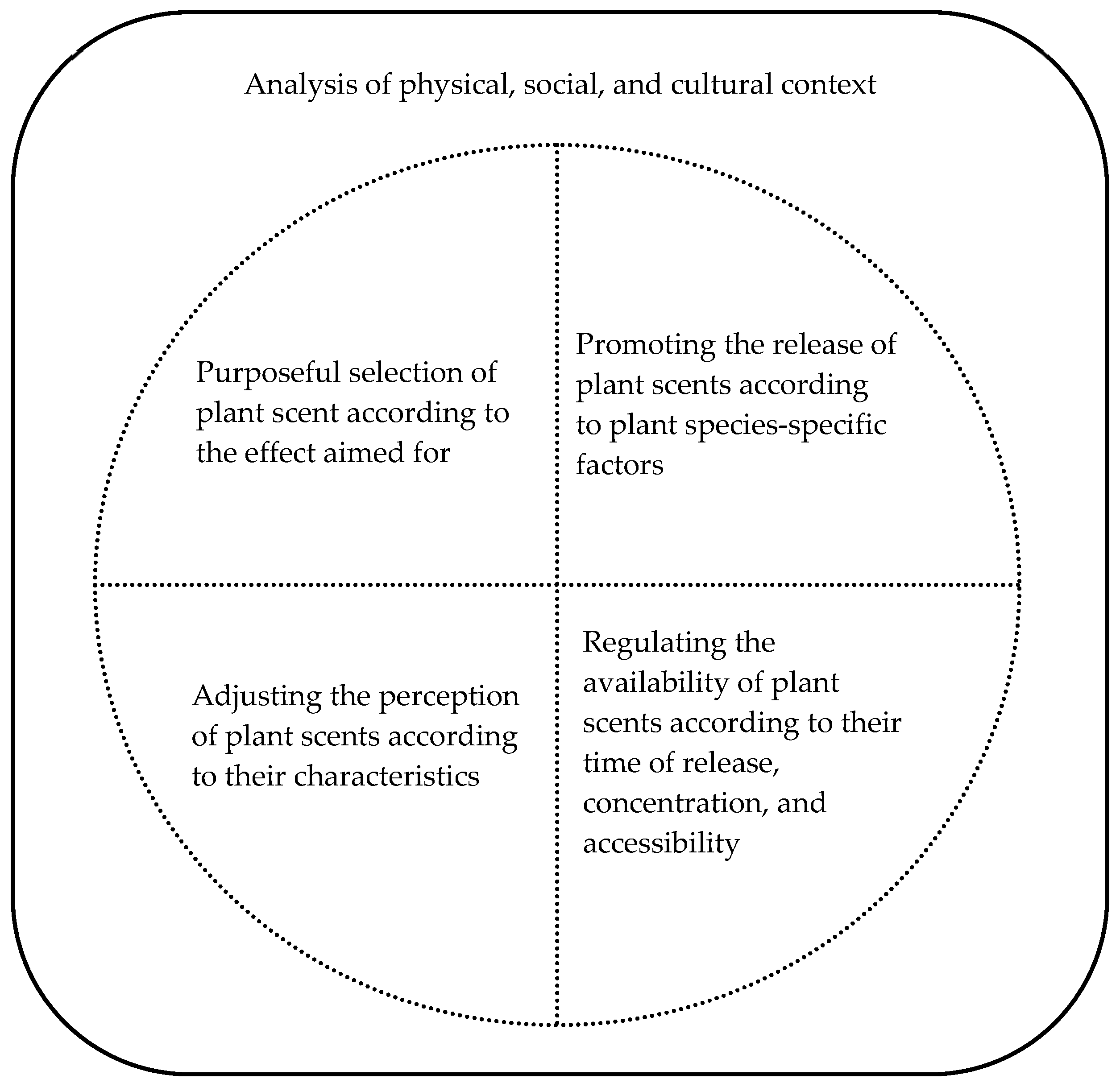

The framework is based on the findings from a review of the literature and the exploration of the use of plant scent in Danner’s Garden and the MAC and provides a structure for purposefully integrating plant scent into the design of the urban green spaces (see

Figure 2). The framework deals with five topics: context analysis, purposeful selection, promoting release, adjusting perception, and regulating availability. The context analysis set the premise of the project in question and can be seen as a basis for designing with plant scent. In

Figure 2 this is illustrated by the framing figure, whereas the four topics placed in the circle are concerned with managing plant scent in relation to the smell environment and the perception aimed for. The dotted lines refer to the fact that the five topics are interdependent and mutually influence each other when making decisions about a design.

3.1. Analysis of Physical, Social, and Cultural Context

Designing with plant scent should always be seen in relation to the overall aim of the landscape architectural project and its context, including its future users and physical, social and cultural environment. Based on a sensory study of a heritage site, Davis and Thys-Şenocak point out that smell can serve as a catalyst for memories, emotions, and values for individuals and communities [

34]. This highlights the value of scent in defining locality and calls for an engagement with future users and their preferences. This integration of user feedback into the design process is relevant both pre-design and post-occupation. Related to the physical context, and in line with the first step of Henshaw’s four-step process, this framework includes a preliminary analysis at the site level [

23]. This consists of an analysis of several physical conditions, including sun/shade, temperature, soil, water, wind/shelter, human traffic (where and when), and existing smell sources [

25], including odor nuisances [

26].

The context analysis of the Danner’s Garden project revealed several challenges, considering that the garden is in the city center of Copenhagen and has a socially and culturally diverse group of people in crisis as its primary users. Traffic noise and fumes, nearby neighbors, shade, and the various needs of vulnerable women and children were taken into consideration, with the overall aim of creating a safe and supportive environment.

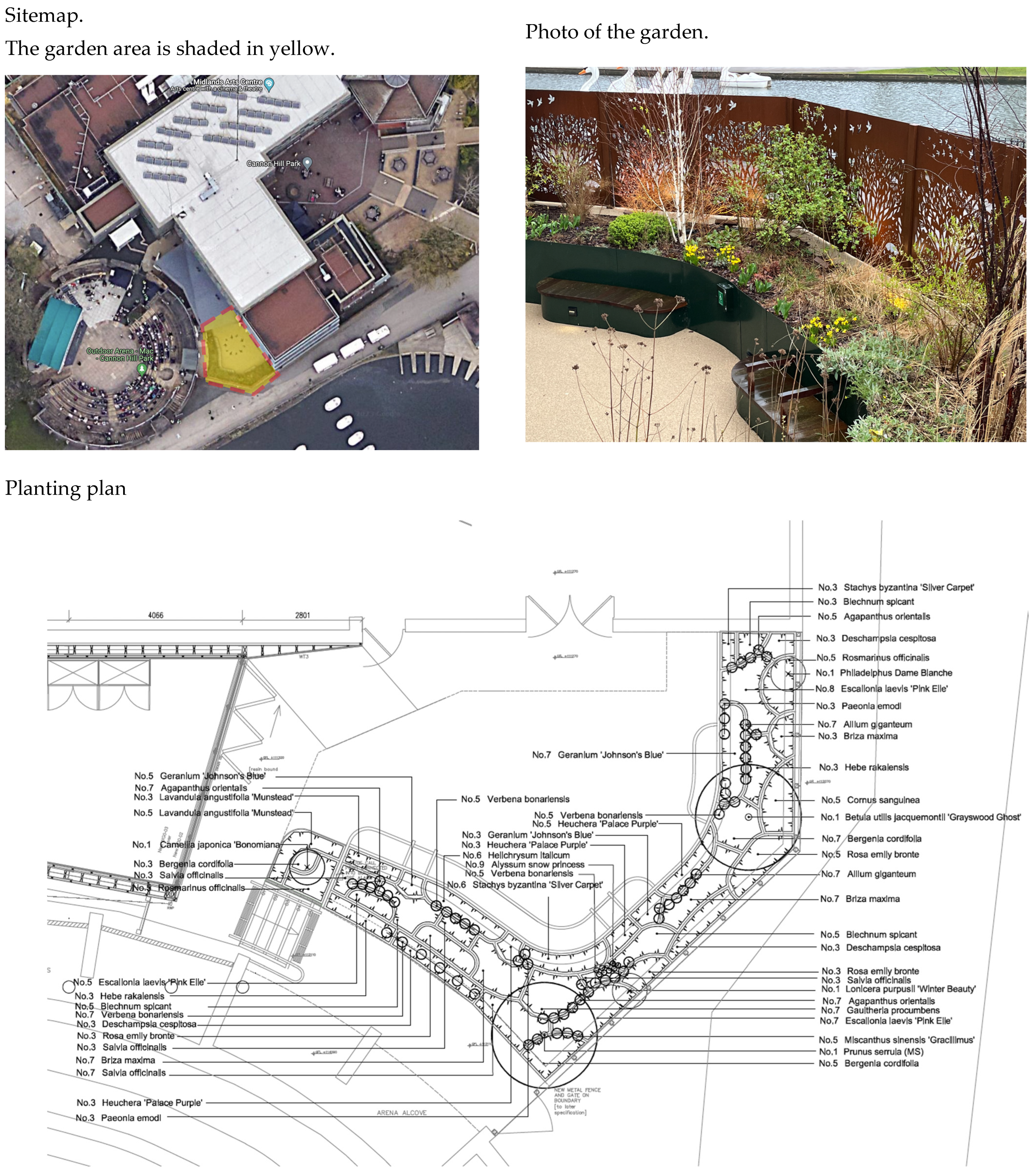

In the case of the MAC, there were no unpleasant odors on the site that needed to be masked. The site was protected from direct exposure to traffic. However, due to the small scale of the site at the MAC, the selection of scented plants and the user’s interaction with plant scents were limited (see

Figure 3). If the project were on a larger scale, there could be opportunities to incorporate various types of scented plants, creating a more dynamic olfactory experience. Collaborating with an experienced gardener has been instrumental in understanding these plants’ growth conditions, which has been a key strength of both projects and contributed to their success.

3.2. Purposeful Selection of Plant Scent According to the Effect Aimed for

To get the most out of the scents, it is essential to choose plant scents based on the purpose of the design and the desired effect. Clarifying the purpose [

23] and selecting appropriate types of fragrant plants [

27] are a crucial part of the framework. Plant scent can be used in many ways in a city’s green space. The literature points out that they can be used to mask bad smells, constitute landmarks, add atmosphere, have a health-promoting purpose, and enhance biodiversity.

In Danner’s Garden, the team aimed to use plant scents as positive distractions for its users experiencing life crises. By distracting positively, these plant scents may awaken interest in the garden and help the users become familiar with it. Moreover, giving the women and children pleasant scent experiences that are potentially linked to emotions and memories can give them mental breaks from their crisis. The selection of plant scent revolved around pleasant scents from flowers, herbs, and berries, with most of them well known in a Danish context, e.g., Hungarian lilac, which characterizes the start of the Danish summer, and oregano, which is often associated with pizza, a common dish for many residents in Denmark. Xiao et al. underline the importance of a strong understanding of local plants and climate conditions as a prerequisite to designing with scented plants, which should be selected according to the local context [

27].

In the MAC case, the artists in residence were the key users of the garden and wished to have a refreshing experience whilst not being overpowered by smells. The design was intended to provide a subtle scent to help the artists settle their thoughts during short breaks in the garden, affecting them at a subconscious level. In the meantime, there was a desire for keeping the garden ‘green’ throughout the year. As a result, the plants selected were mostly shrubs that have evergreen leaves and may blossom during different periods of the year, such as the

Rosa emily bronte,

Bergenia cordifolia, and

Rosmarinus officinalis. The designer admitted that the selection of plants was a safe choice based on their previous experience and that it would be interesting to try out some invigorating scents from plants such as

Lemon balm. Studies into the effect of essential oils suggest that plant scent can affect us on three general levels: the neuropharmacological, the immune-strengthening, and the emotional level [

13]. For example, as previously mentioned, lavender can have a relaxing effect and sage has an anti-inflammatory property. At the same time, an odor-enriched environment generally has a regenerating effect on the brain [

13]. With this garden having a health-promoting purpose, it is essential to choose plant scents based on that desired effect.

If the purpose is to enhance biodiversity and repair the ecosystem, an understanding of local flora, fauna, and climate is a prerequisite [

27]. In this context, the selection of plant scents could, among other things, consider the character of flower scents and the types of animals and insects they attract. For example, mild floral and fruity scents attract bees and butterflies. In contrast, sulfurous smells appeal to bats and rotten smells are preferred by beetles [

35].

Reflecting on the post-occupancy feedback from users, the designers in both cases were pleased with the outcome of the use of plant scent in their designs. Considering the diverse cultural context and focus on future interventions in the Danner’s Garden case, a greater focus on cultural associations was suggested in order to bring people together to evoke a collective emotional response. When dealing with cultural familiarity it can be helpful to start with the place and its context. Within each culture, one can speak of a “common olfactory denominator” that can be seen in the context of culture-specific areas such as ethnicity, diet, clothing habits, scents for the body and home, building materials, and surrounding nature [

22]. This means that we all move around with a cultural scent backdrop and that certain scents have a collective meaning which influences what we like and how we feel upon perceiving them [

22]. The users of Danner’s Garden originate from many different countries, ethnic groups, and parts of society. Chocolate is a popular flavor in many parts of the world, both for adults and children, and could potentially resonate with many users of the garden. This fact could, for example, lead to the introduction of “chocolate scents” from plants such as

Akebia,

Bearded iris,

Berlandiera, and

Chocolate mint.

3.3. Promoting the Release of Plant Scents According to Plant Species-Specific Factors

How and when a plant releases its scent, as well as the character of that scent, depends on the specific species [

9]. Aside from optimal growth conditions, the placement of the plant is critical to the release of its scents because it is stimulated by conditions such as light, temperature, and weather [

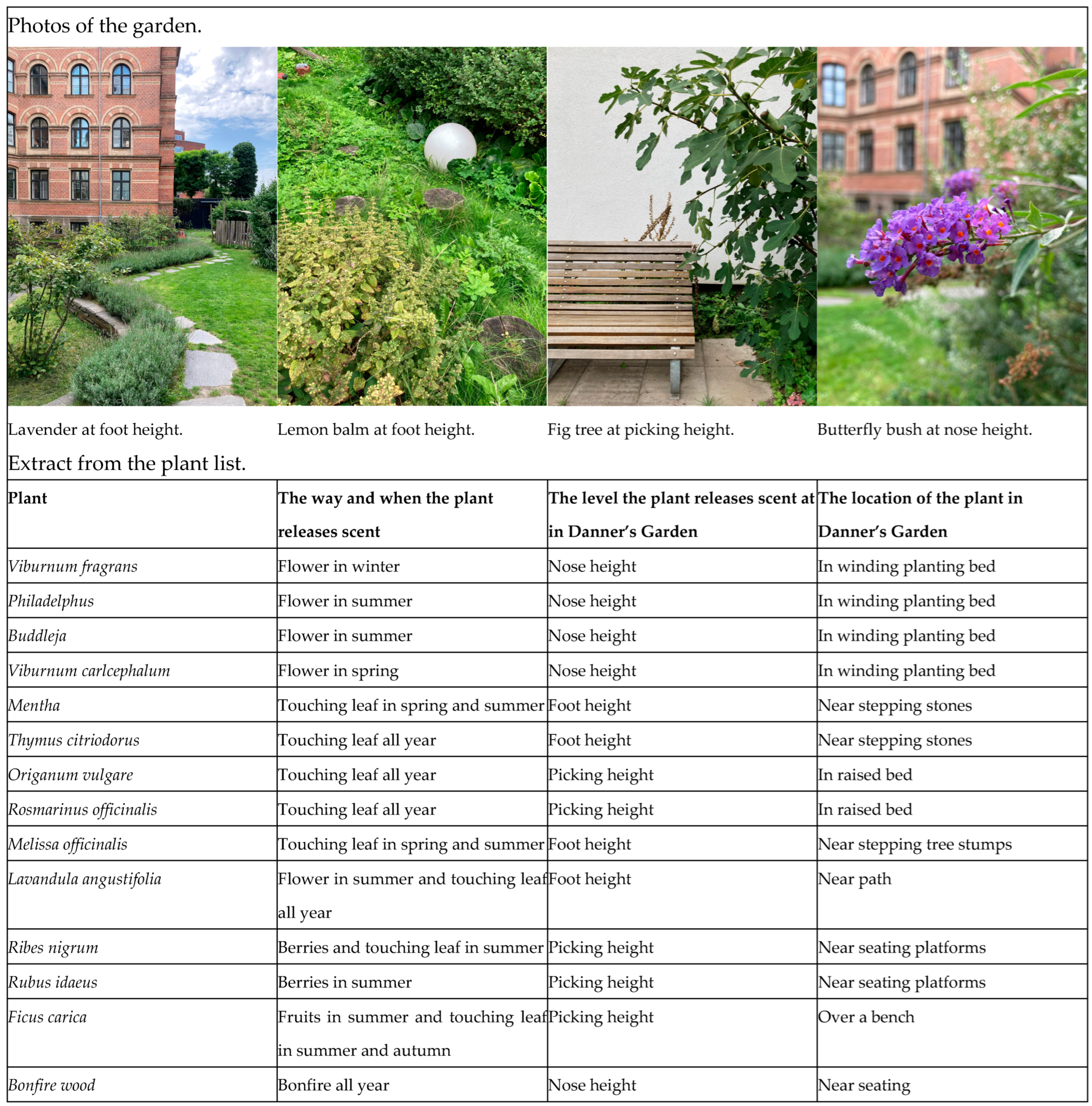

14]. A plant that needs heat to release its scent, for example, needs to be placed in a sunny nook, while a plant that requires pressure on its surface to release its scent should be placed in the rain or under mist from an irrigation system. In fact, the use of sunlight to stimulate certain plant scents in both Danner’s Garden and the MAC is acknowledged. In Danner’s Garden, a fig tree against an end wall that is facing south and absorbs heat from the sunlight helps to release scents from the leaves. Simultaneously considering the best way to promote scent release, location, and the desired scent experience is therefore fundamental in the achievement of an effective design. Danner’s Garden also provides other good examples, with fragrant leaves at foot height near stepping stones,

mint and lemon thyme, and herbs at picking height in raised beds,

oregano and rosemary (see

Figure 4).

To support optimal growth conditions, practical information can be accessed through various sources such as online databases from the Royal Horticultural Society, Gardener’s World, and Gardenia Net. However, further research and systematic reviews on species-specific ways scents can be released need to be carried out.

3.4. Adjusting the Perception of Plant Scents According to Their Characteristics

Understanding the characteristics of plant scents will be useful for designing the desired outcomes. The scent wheel created by Das Gupta et al. classified plant scents into four categories, with three sub-categories in each: intense—chocolate, heady, spicy; dry—resinous, aromatic, anisic; fresh—minty, green, citrus; and sweet—soft, fruity, light [

36]. Different from the psycho-social descriptions of smells, these descriptors give a hint as to the chemical characteristics of these scents and their sources.

Like the art of perfumery, the MAC case considered the characteristics of plant scents, creating a scent journey through top, middle, and base notes to optimize the experience. For example, the intense scents from plants such as jasmine and gardenia will easily stand out in the space as top-note scents; sweet scents from plants such as Sweet pea and rose will be good middle-note scents and can become top-note scents; and dry and fresh scents from plants such as grass and sage are often good base- and middle-note scents. Furthermore, the scent journey, as explained by the designer, is not only about the evolution of scent over time but also a long-term transformation of scents as plants grow. One comment from the conversation we had with the designer prompts us to think of the site as a space for infinite growth and changes. For example, some of the plants will not have any scents in the first few years, such as Peony and Osmanthus fragrans. The scent journey in this case would be sketched out over a 5-year or 10-year period. This will then require the designers to look into the plan for the site over that duration and the impact of any future surrounding developments on the locations of different plants in the design.

The creation of the bonfire in the Danner’s Garden case introduced another method of using plant scent that has also contributed to the garden’s scent journey in a dynamic way, with the contrasting scents of the burnt wood (at night/autumn and winter) and the fresh plants (in the day/spring and summer). Further examination is needed on the impact of humidity and temperature on the perception of different characteristic scents.

3.5. Regulating the Availability of Plant Scents According to Their Time of Release, Concentration, and Accessibility

Paramount for enjoying a plant’s scent is ensuring the optimal growth and maintenance of the plant. Moreover, scents appear and disappear in tune with the life cycle of the plants and weather, which is again related to season and climate. When and how a plant releases its scent in each context must be taken into consideration in order to use plant scent effectively. While an evergreen leaf scent may be available all year round, the scent from a flower can only be enjoyed in flowering season [

14].

Going more into detail, the availability of plant scents includes three aspects: circadian rhythm, detectable concentration, and accessibility. Their concentration in the air can be controlled by adjusting the size and number of plants. Using landscape elements such as bushes as boundaries can separate smells and concentrate plant scents [

27]. Capturing scents in conservatoires is another effective way of making them detectable. In places where increasing the number of plants is not possible or does not fit the scheme, making the fragrant plants accessible, so that they can be touched and sniffed from a close distance, is important.

The circadian rhythm of plants, and the time of the day that the plant releases its scents most strongly, is also crucial for the optimization and availability of scents. For example, night-scented plants such as handy gardenia and honeysuckle would be great choices to introduce into urban landscapes in dense residential areas where people may take a walk after dinner. Their design may consider lighting that guides people to where such plants were located. If lighting is not available, these plants could be planted along the footpaths. Choosing plants that release scents across the four seasons is also important to ensuring the availability of plant scents all year round.

In Danner’s Garden, to cater to availability, the placement of the scented plants was carefully considered in relation to where and when people walk through or stay in the garden. For example,

lavender hedges run along a path from the entrance of the garden to a good way into it (see

Figure 5, the hedges separating areas 6 and 7). Near the kids’ play area and the seating on the east terrace,

blackcurrants, raspberries, blueberries, and wild strawberries were used for interactions, picking, and eating (see

Figure 5, area 3 and 6). Fragrant bushes were designed pointwise and at nose height in a winding planting belt:

butterfly bush, mock-orange, fragrant snowball, and the winter-blooming

Viburnum Fragrans (see

Figure 5, the winding planting bed on the right-hand side of areas 3). Users making visual connections between scents and plants also stimulates their odor imagination and invites them to sniff, as in the MAC case, where the seats are orientated towards a cluster of

Geranium ‘Johnson’s Blue’ with radiant purple–blue flowers.

4. Discussion: The Challenges of Working with Plant Scents

One challenge revealed by the Danner’s Garden project is the individual preference for smells, which can vary according to personal experiences, gender, age, and state of health. Some plants smell terrible, and should generally be avoided, but even if a plant scent is most often considered to be something pleasant, the distance between a good quality and nuisance can be short. This applies especially to strong plant scents such as lilies or lilacs. Experience from the MAC case points to the fact that an initial-stage user group meeting to decide on the characteristics of the scents in the design is potentially a good approach to identify what is unwanted in particular. Specifically, when designing for vulnerable people it can be a good idea to include the possibility of deselecting plant scents. The women and children at Danner are in a state of crisis and can be affected by numerous health consequences, including headache, which can be triggered and worsened by smell. In retrospect, this aspect could have been much more in focus when working with plant scent in the design process. One way of dealing with this issue could be, for example, to incorporate flexibility in the design in relation to the way people come into contact with the scents. Plants that require physical contact to release their smell are good in that respect, because people can control their scents themselves. In addition, strong flower scents can be avoided at places of residence, along heavily traveled routes, and indoors in, for example, conservatories.

Another challenge is the lack of knowledge on the connections between flower scents and insects in the local ecosystem. However, this area also has huge potential to be researched in the future to enhance biodiversity and repair ecosystems from a scent perspective. Unfortunately, neither project had an ecologist onboard. Plant scent selection should ideally consider the characteristics of flower scents and the types of animals and insects they attract.

Yet another challenge identified from the conversations we had might be dealing with non-plant smells onsite. In the Danner’s Garden case, an area under the pergola was designated for users to smoke in. The designer did not want to separate the smokers from the rest of the garden and kept its visual connections and access to freshness. This is, in fact, difficult to manage with a completely outdoor open-space setting. Positioning such spaces in upwind directions and separating user paths will be essential. This will bring attention to the initial discussions about site readings for initial planning. A much more detailed study will be needed in such cases on the airflow and dispersion of ‘other scents’ in simulation software.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that our experience of the environment is multisensory and that smell is just one of numerous sensory impressions. Soundscapes, color schemes, etc., are also part of a good design and should be addressed alongside the smellscape to create a harmonious multisensory environment. To achieve this, future research could focus on expanding the framework to form a more comprehensive multisensory design strategy.

5. Conclusions

Working in a targeted manner with plant scents is no easy task. There are many factors to take into account and many aspects that must come together in order to achieve one’s goal. However, it is hoped that this framework will make it a little easier to proceed systematically and get a handle on many of the parameters that apply. This framework goes into depth on the relations between the nature of plant scent, how to make it accessible through design, and what effects plant scent can have on us and the environment. Plant scent is often nicely incorporated into sensory gardens, but is actually always present in all green spaces, so why not work actively with scents so that they contribute positively to the overall aim of a green space and can create enhanced biodiversity and better living conditions and health for city dwellers. The practical guidance and discussion in this article will contribute to future design practices, from developing conceptual ideas about integrating plant scents to implementing these schemes in reality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L.L.; Methodology, V.L.L. and J.X.; Investigation, V.L.L. and J.X.; Formal analysis, V.L.L. and J.X.; Writing—original draft, V.L.L. and J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data were obtained and processed in compliance with the rules of the General Data Protection Regulation.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the interviewees and respective architectural firms for sharing their knowledge and illustrations. Thanks should also go to Danner for welcoming us into their garden despite their high-level safety requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Holl, S.; Pallasmaa, J.; Pérez-Gómez, A. Questions of Perception—Phenomenology of Architecture; William Stout Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wankhede, K.; Deshmukh, A.; Wahurwagh, A.; Patil, A.; Varma, M. An insight into the urban smellscape: The transformation of traditional to contemporary urban place experience. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 3818–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Aletta, F.; Radicchi, A.; McLean, K.; Shiner, L.E.; Verbeek, C. Recent Advances in Smellscape Research for the Built Environment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 700514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, R. Smelling therapeutic landscapes: Embodied encounters within spaces of care farming. Health Place 2017, 47, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Hao, Z.; Li, L.; Ye, T.; Sun, B.; Wu, R.; Pei, N. Sniff the urban park: Unveiling odor features and landscape effect on smellscape in Guangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 78, 127764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vautz, W.; Hariharan, C.; Weigend, M. Smell the change: On the potential of gas-chromatographic ion mobility spectrometry in ecosystem monitoring. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 4370–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, R. The Scent of Orchids—Olfactory and Chemical Investigations; Editiones Roche: Basel, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, O. (Ed.) Dufttunnel/Scent Tunnel; Hatje Cantz: Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings, R. Healing Gardens. Aromatheraphy, Feng Shui, Holistic Gardening, Herbalism, Color Theraphy, Meditation; Willow Creek Press: Minocoqua, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H.; Fujii, E.; Cho, T. An experimental study on physiological and psychological effects of pine scent. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2010, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Nakadai, A.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Shimizu, T.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; et al. Forest bathing enhances human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2007, 20 (Suppl. S2), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pálsdóttir, A.M.; Spendrup, S.; Mårtensson, L.; Wendin, K. Garden smellscape–experiences of plant scents in a nature-based intervention. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 667957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, N.; Perry, E. Aromatherapy in the Management of Psychiatric Disorders—Clinical and Neuropharmacological Perspectives. CNS Drugs 2006, 20, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, S. Scent in Your Garden; Frances Lincoln: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, E.; Sand, O.; Sjaastad, Ø.V. Menneskets Fysiologi; G.E.C. Gads Forlag: København, Denmark, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Buck, L.B. Unraveling the Sense of Smell (Nobel lectures). In Angewandte Chemie International, 44th ed.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 6128–6140. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton Frosell, P. Fra Duftenes Verden—Parfumerne og Deres Historie; Hernovs Forlag: København, Denmark, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, P.H.; Evert, R.F.; Eichhorn, S.E. Biology of Plants; W.H. Freeman and Company Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg-Pedersen, A.; Meyhoff, K.W. At Se Sig Selv Sanse—Samtaler Med Olafur Eliasson; Informations Forlag: København, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist. Scents and sensitivity—Subliminal smells can have powerful effects. Economist 2007, 88. Available online: https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2007/12/06/scents-and-sensitivity (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Proust, M. På Sporet af Den Tabte Tid—Swanns Verden; Multivers: København, Danmark, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, J. Lugten af Penge—Om Duftmarketing; MERKO Gyldendal Uddannelse: København, Denmark, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw, V. Urban Smellscapes: Understanding and Designing City Smell Environments; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R.; Romice, O. Assessing the multi-sensory qualities of urban space: A methodological approach and notational system for recording and designing the multi-sensory experience of urban space. Psyecology 2010, 1, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, K. Communicating and mediating smellscapes: The design and exposition of olfactory mappings. In Designing with Smell: Practices, Techniques and Challenges; Henshaw, V., McLean, K., Medway, D., Perkins, C., Warnaby, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, M. IAQM Guidance on the Assessment of Odour for Plannin—Version 1.1; Institute of Air Quality Management: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Tait, M.; Kang, J. The design of urban smellscapes with fragrant plants and water features. In Designing with Smell: Practices, Techniques and Challenges; Henshaw, V., McLean, K., Medway, D., Perkins, C., Warnaby, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, M. Learning from Experience: Approaches to the experiential component of practice-based research. In Forskning-Reflektion-Utveckling; Swedish Research Council, Vetenskapsrådet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2004; pp. 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Health Design. An Introduction to Evidence-Based Design: Exploring Healthcare and Design, 2nd ed.; Center for Health Design: Concord, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, U.K.; Sidenius, U. Keeping Promises—How to Attain the 388 Goal of Designing Health-Supporting Urban Green Space. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2020, 8, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygum, V.L.; Poulsen, D.V.; Djernis, D.; Djernis, H.G.; Sidenius, U.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Post-Occupancy Evaluation of a Crisis Shelter Garden and Application of Findings Through the Use of a Participatory Design Process. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2019, 12, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, J.; Hetherington, R.; Lovell, M.; McConaghy, J.; Viczko, M. Draw me a picture, tell me a story: Evoking memory and supporting analysis through pre-interview drawing activities. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 58, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.; Thys-Şenocak, L. Heritage and Scent: Research and Exhibition of Istanbul’s Changing Smellscapes. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, O.R.P. Pourquoi ca sent? Les fleurs. Nez 2017, 3, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Das Gupta, L.; Hall, L.; Hurrion, D. The wheel of scent. Gardeners’ World 2012, 96–105. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).