How Can We Measure Urban Green Spaces’ Qualities and Features? A Review of Methods, Tools and Frameworks Oriented Toward Public Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

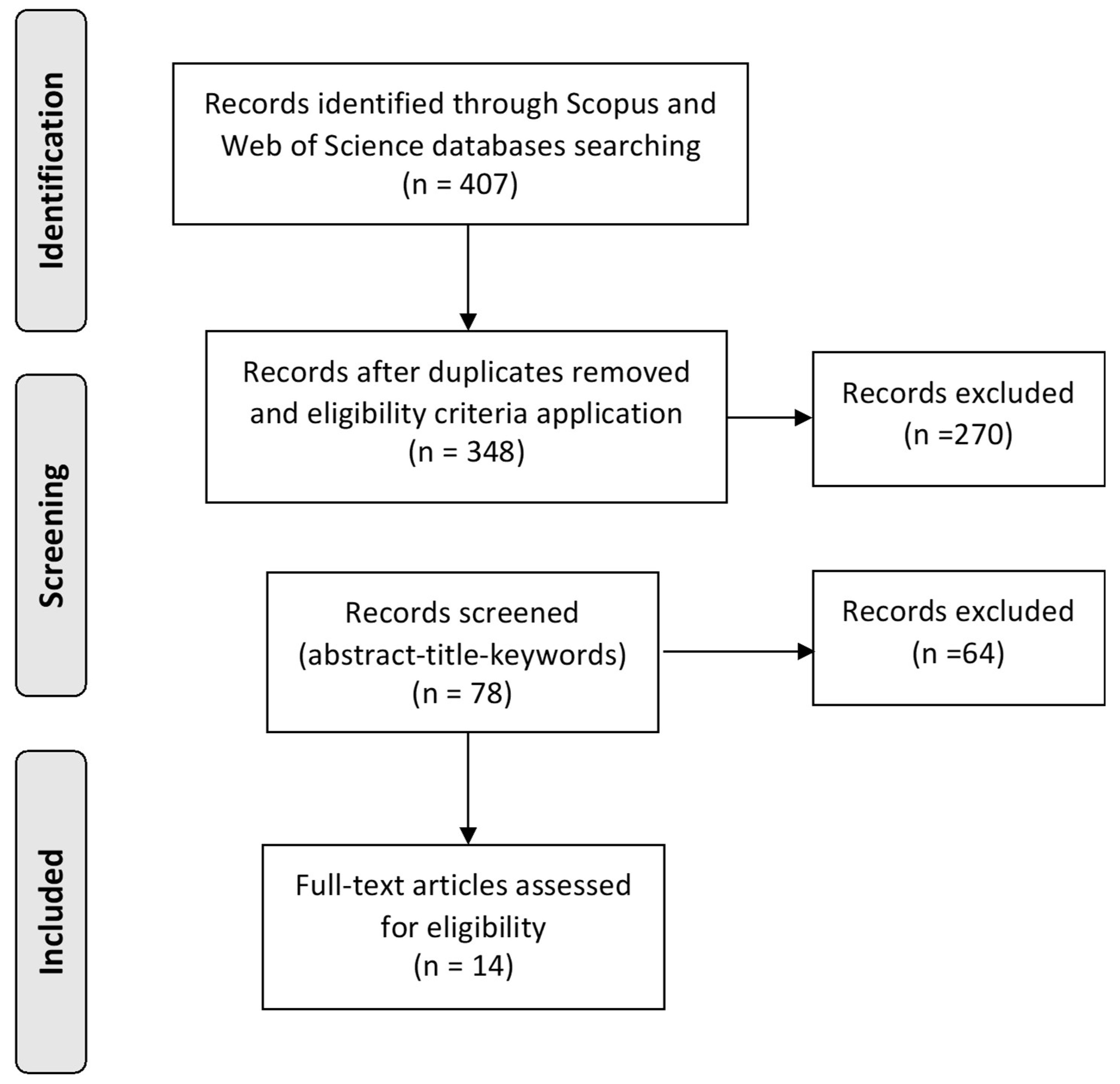

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Tools Structure

3.2. Dimensions of Quality Evaluated

3.3. Data Collection Methods

| Article | Tool Name | Surveys | GIS-Based Mapping | Field Observations | Remote Sensing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajmi et al. (2023) [29] | UGS QIndex | x | |||

| Buffoli et al. (2022) [1] | RECITAL 2.0 Milano | x | |||

| Dong et al. (2024) [36] | Evaluation Indexes for UGS | x | x | x | |

| Ghale et al. (2023) [37] | Composite Green Space Index (CGSI) | x | x | x | |

| Hänchen et al. (2024) [4] | Green Infrastructure Connectivity Tool | x | |||

| Hou, Y. et al. (2024) [32] | Supply Adjustment Index (SAI) | x | x | ||

| Knobel et al. (2021) A–B [30,31] | RECITAL | x | |||

| Olszewska-Guizzo et al. (2023) [20] | Contemplative Landscape Model (CML) | x | |||

| Semenzato et al. (2023) [25] | UGS Accessibility indicators | x | x | ||

| Tohoun et al. (2023) [38] | Mixed Methods Accessibility Tool | x | x | ||

| Wirtz Baker et al. (2024) [39] | Google Street View Assessment Tool | x | x |

3.4. Location and Scope

3.5. Relationship with Health and Well-Being

3.6. Technological Innovations and Tool Limitations

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CLM | Contemplative Landscape Model |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease of 2019 |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GSV | Google Street View |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| LST | Land Surface Temperature |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NDMI | Normalized Difference Moisture Index |

| NEST | Natural Environment Scoring Tool |

| PET | physiological equivalent temperature |

| POS | Public Open Space |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RECITAL | uRban grEen spaCe qualITy Assessment tool |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UGS | Urban Green Spaces |

References

- Buffoli, M.; Villella, F.; Voynov, N.S.; Rebecchi, A. Urban Green Space to Promote Urban Public Health: Green Areas’ Design Features and Accessibility Assessment in Milano City, Italy. In New Metropolitan Perspectives; Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 482, pp. 1966–1976. ISBN 978-3-031-06824-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Mora, S.; Preisler, Y.; Duarte, F.; Prasad, V.; Ratti, C. Tools and Methods for Monitoring the Health of the Urban Greenery. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffoli, M.; Rebecchi, A. The Proximity of Urban Green Spaces as Urban Health Strategy to Promote Active, Inclusive and Salutogenic Cities. In Technological Imagination in the Green and Digital Transition; Arbizzani, E., Cangelli, E., Clemente, C., Cumo, F., Giofrè, F., Giovenale, A.M., Palme, M., Paris, S., Eds.; The Urban Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1017–1027. ISBN 978-3-031-29514-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hänchen, L.; Hecht, R.; Reiter, D. Indicators for Assessing the Supply, Demand and Accessibility of Urban Green Spaces in the Context of a Planning Instrument; Wichmann Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; ISBN 978-3-87907-752-6. [Google Scholar]

- Portela, C.I.; Massi, K.G.; Rodrigues, T.; Alcântara, E. Impact of Urban and Industrial Features on Land Surface Temperature: Evidences from Satellite Thermal Indices. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 56, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasobant, S.; Lekha, K.S.; Trivedi, P.; Krishnan, S.; Kator, C.; Kaur, H.; Adaniya, M.; Sinha, A.; Saxena, D. Impact of Heat on Human and Animal Health in India: A Landscape Review. Dialogues Health 2025, 6, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konijnendijk, C.C. Evidence-Based Guidelines for Greener, Healthier, More Resilient Neighbourhoods: Introducing the 3–30–300 Rule. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolongo, S.; Rebecchi, A.; Buffoli, M.; Appolloni, L.; Signorelli, C.; Fara, G.M.; D’Alessandro, D. COVID-19 and Cities: From Urban Health Strategies to the Pandemic Challenge. A Decalogue of Public Health Opportunities. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfredi, V.; Buffoli, M.; Rebecchi, A.; Croci, R.; Oradini-Alacreu, A.; Stirparo, G.; Marino, A.; Odone, A.; Capolongo, S.; Signorelli, C. Association between Urban Greenspace and Health: A Systematic Review of Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaroni, H.; Amorim, J.H.; Hiemstra, J.A.; Pearlmutter, D. Urban Green Infrastructure as a Tool for Urban Heat Mitigation: Survey of Research Methodologies and Findings across Different Climatic Regions. Urban Clim. 2018, 24, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, M.; Beenackers, M.A.; Timmeren, A.V.; Pottgiesser, U. Urban Green Spaces, Self-Rated Air Pollution and Health: A Sensitivity Analysis of Green Space Characteristics and Proximity in Four European Cities. Health Place 2024, 89, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal Yañez, D.; Pereira Barboza, E.; Cirach, M.; Daher, C.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Mueller, N. An Urban Green Space Intervention with Benefits for Mental Health: A Health Impact Assessment of the Barcelona “Eixos Verds” Plan. Environ. Int. 2023, 174, 107880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lange, K.W. Assessing the Relationship between Urban Blue-Green Infrastructure and Stress Resilience in Real Settings: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Guo, P.; Guo, X. Effects of Urban Green Space (UGS) Quality on Physical Activity (PA) and Health, Controlling for Environmental Factors. J. Infras. Policy. Dev. 2024, 8, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.J.; Rahaman, M.; Hossain, S.I. Urban Green Spaces for Elderly Human Health: A Planning Model for Healthy City Living. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, P.Y.; Diehl, J.A. A Conceptual Framework for Studying Urban Green Spaces Effects on Health. J. Urban Ecol. 2017, 3, jux015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, M.; Beenackers, M.A.; Fleury-Bahi, G.; Bodénan, P.; Petrova, M.T.; Van Timmeren, A.; Pottgiesser, U. Examining Green Space Characteristics for Social Cohesion and Mental Health Outcomes: A Sensitivity Analysis in Four European Cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 93, 128230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakınlar, N.; Akpınar, A. How Perceived Sensory Dimensions of Urban Green Spaces Are Associated with Adults’ Perceived Restoration, Stress, and Mental Health? Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 72, 127572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobel, P.; Dadvand, P.; Maneja-Zaragoza, R. A Systematic Review of Multi-Dimensional Quality Assessment Tools for Urban Green Spaces. Health Place 2019, 59, 102198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska-Guizzo, A.; Sia, A.; Escoffier, N. Revised Contemplative Landscape Model (CLM): A Reliable and Valid Evaluation Tool for Mental Health-Promoting Urban Green Spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 86, 128016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelata, A. Reducing Outdoor Air Temperature, Improving Thermal Comfort, and Saving Buildings’ Cooling Energy Demand in Arid Cities—Cool Paving Utilization. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 68, 102762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.C.K.; Maheswaran, R. The Health Benefits of Urban Green Spaces: A Review of the Evidence. J. Public Health 2011, 33, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.-Y.; Astell-Burt, T.; Rahimi-Ardabili, H.; Feng, X. Green Space Quality and Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiqiu, Z.; Xinlei, D.; Yajuan, W.; Wenguo, W.; Mingjing, W. GIS-Based Accessibility Analysis of Urban Park Green Space Landscape. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenzato, P.; Costa, A.; Campagnaro, T. Accessibility to Urban Parks: Comparing GIS Based Measures in the City of Padova (Italy). Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, B.; Di Martino, F.; Mauriello, C.; Miraglia, V. A GIS-Based Framework to Analyze the Behavior of Urban Greenery During Heatwaves Using Satellite Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, T.; Li, J.; Yang, G.; Zhao, L.; Cao, Q.; Yang, L.; Sun, Y. Advancing Sustainability in Urban Planning by Measuring and Matching the Supply and Demand of Urban Green Space Ecosystem Services. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W65–W94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmi, R.; Allouche, F.K.; Taîbi, A.N.; Boussema, S.B.F. Developing a Qualitative Urban Green Spaces Index Applied to a Mediterranean City. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobel, P.; Dadvand, P.; Alonso, L.; Costa, L.; Español, M.; Maneja, R. Development of the Urban Green Space Quality Assessment Tool (RECITAL). Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobel, P.; Maneja, R.; Bartoll, X.; Alonso, L.; Bauwelinck, M.; Valentin, A.; Zijlema, W.; Borrell, C.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Dadvand, P. Quality of Urban Green Spaces Influences Residents’ Use of These Spaces, Physical Activity, and Overweight/Obesity. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 271, 116393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L. Assessing Inequality in Urban Green Spaces with Consideration for Physical Activity Promotion: Utilizing Spatial Analysis Techniques Supported by Multisource Data. Land 2024, 13, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlow, C.; Van Kempen, E.; Smith, G.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Kruize, H.; Gražulevičienė, R.; Ellis, N.; Hurst, G.; Masterson, D.; Cirach, M.; et al. Development of the Natural Environment Scoring Tool (NEST). Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Broomhall, M.H.; Knuiman, M.; Collins, C.; Douglas, K.; Ng, K.; Lange, A.; Donovan, R.J. Increasing Walking. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska, A.A.; Marques, P.F.; Ryan, R.L.; Barbosa, F. What Makes a Landscape Contemplative? Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Feng, C.; Yue, B.; Zhang, Z. An Evaluation Model of Urban Green Space Based on Residents’ Physical Activity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghale, B.; Gupta, K.; Roy, A. Evaluating public urban green spaces: A composite green space index for measuring accessibility and spatial quality. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohoun, B.A.; Sapena, M.; Mast, J.; Taubenböck, H.; Haruna, I.; Orekan, V.; Okhimamhe, A.A. Are Citizens’ Perceptions on Urban Green Spaces Influenced by Their Immediate Environment? The Case of Grand Nokoue, Benin Republic. In Proceedings of the 2023 Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event (JURSE), Heraklion, Greece, 17 May 2023; IEEE: Heraklion, Greece, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz Baker, J.M.; Aballay, L.R.; Haluszka, E.; Niclis, C.; Staurini, S.; Lambert, V.; Pou, S.A. Exploring the Quality of Urban Green Spaces and Their Association with Health: An Epidemiological Study on Obesity Using Street View Technology. Public Health 2024, 237, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaus, M.; Haase, D. Green Roof Effects on Daytime Heat in a Prefabricated Residential Neighbourhood in Berlin, Germany. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 53, 126738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspari, J.; Fabbri, K.; Lucchi, M. The Use of Outdoor Microclimate Analysis to Support Decision Making Process: Case Study of Bufalini Square in Cesena. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noro, M.; Lazzarin, R. Urban Heat Island in Padua, Italy: Simulation Analysis and Mitigation Strategies. Urban Clim. 2015, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Paper | Title | Authors | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ajmi et al. (2023) [29] | Developing a Qualitative Urban Green Spaces Index Applied to a Mediterranean City | Ajmi, R.; Allouche, F.K.; Taîbi, A.N.; Boussema, S.B.F. | 2023 |

| Article | Tool Name | Number of Items | Evaluation Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ajmi et al. (2023) [29] | UGS QIndex | 41 items | Likert scale |

| Buffoli et al. (2022) [1] | RECITAL 2.0 Milano | 6 dimensions | Likert scale (5-point) |

| 75 items | |||

| Dong et al. (2024) [36] | Evaluation Indexes for UGS | 6 dimensions | Composite index + GIS metrics |

| Ghale et al. (2023) [37] | Composite Green Space Index (CGSI) | 6 dimensions | Composite index |

| Hänchen et al. (2024) [4] | Green Infrastructure Connectivity Tool | 3 dimensions | GIS metrics |

| 5 indicators | |||

| Hou, Y. et al. (2024) [32] | Supply Adjustment Index (SAI) | 3 dimensions | Composite index |

| 9 items | |||

| Knobel et al. (2021) A-B [30,31] | RECITAL | 9 dimensions | Likert Scale (5-point) |

| 90 items | |||

| Olszewska-Guizzo et al. (2023) [20] | Contemplative Landscape Model (CML) | 7 items | Likert scale (6-point) |

| Semenzato et al. (2023) [25] | UGS Accessibility indicators | 10 indicators | Composite index +GIS metrics |

| Tohoun et al. (2023) [38] | Mixed Methods Accessibility Tool | 2 dimensions | Composite index |

| Wirtz Baker et al. (2024) [39] | Google Street View Assessment Tool | 8 dimensions | Likert scale (5-point) |

| 58 items |

| Article | Tool Name | Accessibility | Safety | Aesthetics | Biodiversity | Social Aspects | Facilities | Amenities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajmi et al. (2023) [29] | UGS QIndex | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Buffoli et al. (2022) [1] | RECITAL 2.0 Milano | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Dong et al. (2024) [36] | Evaluation Indexes for UGS | x | x | x | x | |||

| Ghale et al. (2023) [37] | Composite Green Space Index (CGSI) | x | x | x | ||||

| Hänchen et al. (2024) [4] | Green Infrastructure Connectivity Tool | x | ||||||

| Hou, Y. et al. (2024) [32] | Supply Adjustment Index (SAI) | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Knobel et al. (2021) A–B [30,31] | RECITAL | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Olszewska-Guizzo et al. (2023) [20] | Contemplative Landscape Model (CML) | x | x | |||||

| Semenzato et al. (2023) [25] | UGS Accessibility indicators | x | x | |||||

| Tohoun et al. (2023) [38] | Mixed Methods Accessibility Tool | x | x | |||||

| Wirtz Baker et al. (2024) [39] | Google Street View Assessment Tool | x | x | x | x | x |

| Article | Location | Scope |

|---|---|---|

| Ajmi et al. (2023) [29] | Tunisia | Local parks. The tools are applied to local parks in Tunisia, focusing on small green spaces within densely populated urban contexts, aiming to improve accessibility and aesthetics for residents |

| Buffoli et al. (2022) [1] | Milan, Italy | The RECITAL tool is applied to urban green spaces in Milan to evaluate their quality and impact on public health, focusing on improving accessibility, aesthetics, and safety within densely populated neighborhoods. |

| Dong et al. (2024) [36] | Hunan, China | To quantify the key values of UGSs, which are set as the evaluation indexes, to investigate their impacts on residents’ Physical Activity based on the six UGSs in Changsha city, Hunan Province China. |

| Ghale et al. (2023) [37] | Dehradu, India | This study develops a Composite Green Space Index (CGSI) to assess accessibility and spatial quality of public urban green spaces in Dehradun, India, integrating GIS analysis with multi-criteria evaluation to support urban planning. |

| Hänchen et al. (2024) [4] | Munich, Germany | Introduce a comprehensive set of GIS-based indicators designed to assess the supply, demand, and accessibility of UGSs, applied in Munich. |

| Hou, Y. et al. (2024) [32] | Harbin, China | Consider different types of UGSs in inequality assessments, applied in Harbin city of China. |

| Knobel et al. (2021) A–B [30,31] | Barcelona, Spain | A—Development of a multidimensional in situ quality assessment tool for urban green spaces and application in 149 urban green spaces in Barcelona, Spain. B—Analysis of the correlation between UGS quality and health-related outcomes. |

| Olszewska-Guizzo et al. (2023) [20] | Global (mostly Asia) | Validation of a revised version of the Contemplative Landscape Model (CLM), to assess the visual quality of UGSs in predicting mental health and well-being benefits. |

| Semenzato et al. (2023) [25] | Padova, Italy | Development and evaluation of multiple accessibility indicators for urban parks, integrating GIS-based methods to assess disparities in park access and inform urban planning. |

| Tohoun et al. (2023) [38] | Africa, Benin | Evaluates spatial patterns of UGSs and their relationship with citizens’ perceptions using surveys and remote sensing, highlighting variations in perceived benefits across different urban contexts. |

| Wirtz Baker et al. (2024) [39] | Argentina, Cordoba | Explore the quality of UGSs and its association with obesity in Cordoba, Argentina, using Google Street View images. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rebecchi, A.; Mosca, E.I.; Capolongo, S.; Buffoli, M.; Mangili, S. How Can We Measure Urban Green Spaces’ Qualities and Features? A Review of Methods, Tools and Frameworks Oriented Toward Public Health. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120544

Rebecchi A, Mosca EI, Capolongo S, Buffoli M, Mangili S. How Can We Measure Urban Green Spaces’ Qualities and Features? A Review of Methods, Tools and Frameworks Oriented Toward Public Health. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):544. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120544

Chicago/Turabian StyleRebecchi, Andrea, Erica Isa Mosca, Stefano Capolongo, Maddalena Buffoli, and Silvia Mangili. 2025. "How Can We Measure Urban Green Spaces’ Qualities and Features? A Review of Methods, Tools and Frameworks Oriented Toward Public Health" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120544

APA StyleRebecchi, A., Mosca, E. I., Capolongo, S., Buffoli, M., & Mangili, S. (2025). How Can We Measure Urban Green Spaces’ Qualities and Features? A Review of Methods, Tools and Frameworks Oriented Toward Public Health. Urban Science, 9(12), 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120544